Abstract

Background

While the psychosocial risk factors for traumatic injuries have been comprehensively investigated, less is known about psychosocial factors predisposing athletes to overuse injuries.

Objective

The aim of this review was to systematically identify studies and synthesise data that examined psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries in athletes.

Design

Systematic review.

Data Sources

MEDLINE, Web of Science and PsycINFO databases, supplemented by hand searching of journals and reference lists.

Eligibility Criteria for Selecting Studies

Quantitative and qualitative studies involving competitive athletes, published prior to July 2021, and reporting the relationship between psychosocial variables and overuse injury as an outcome were reviewed. This was limited to academic peer-reviewed journals in Swedish, English, German, Spanish and French. An assessment of the risk of bias was performed using modified versions of the RoBANS and SBU Quality Assessment Scale for Qualitative Studies.

Results

Nine quantitative and five qualitative studies evaluating 1061 athletes and 27 psychosocial factors were included for review. Intra-personal factors, inter-personal factors and sociocultural factors were found to be related to the risk of overuse injury when synthesised and reported according to a narrative synthesis approach. Importantly, these psychosocial factors, and the potential mechanisms describing how they might contribute to overuse injury development, appeared to be different compared with those already known for traumatic injuries.

Conclusions

There is preliminary evidence that overuse injuries are likely to partially result from complex interactions between psychosocial factors. Coaches and supporting staff are encouraged to acknowledge the similarities and differences between traumatic and overuse injury aetiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

The findings in this review identified potential psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries. |

The 27 identified factors were categorised into intra-personal factors, inter-personal factors and sociocultural factors. Stress was identified as one of the risk factors, which is similar to studies in traumatic injuries. |

Psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries are an underexplored area. Prospective studies with repeated measures are needed in future studies, as well as an agreement over the definition and operationalisation of these types of injuries. |

1 Introduction

Overuse injuries are highly prevalent in sports with repetitive movement such as athletics [1], tennis [2], volleyball, handball, cycling, floorball [3] and swimming [4]. These injuries are problematic because they are related to negative consequences such as poorer performance [5], high cost for rehabilitation [6] and retirement from sport [7]. Nearly one out of two former professional soccer players retired from English professional football because of injury, of which 58% were overuse injuries [8]. The pathology of overuse injuries is different from traumatic injuries and the aetiology needs to be investigated before preventive strategies can be evaluated.

In a comprehensive model for injury causation, internal and external risk factors have been discussed [9]. The authors concluded that the inciting event can be distant from the occurrence of an injury. This is because all injuries do not occur at a single event even though the pain can have an acute onset, for example overuse injuries. Overuse injuries develop most often because of repetitive loading of the musculoskeletal system without adequate rest that allows the structures to adapt to the training load and may occur suddenly without identified events [10,11,12], while traumatic injuries occur at an identified specific event with or without contact with another person or object, for example ankle sprain [13, 14]. An imbalance between training load and recovery was therefore described as a key factor for explaining how overuse injuries may occur [15,16,17]. Risk factors for overuse injuries have mainly been described in terms of training load, [16] cyclic chain of shifting circumstances [18], performance level and previous injury [19]. Because of the gradual onset of an overuse injury, a multifactorial explanation including bio-psychosocial factors is more evident [20], for example psychosocial stress reduces the muscle recovery after resistance training [21]. Within the Biopsychosocial Model of Stress, Athletic Injury and Health (BMSAIH) [20], different pathways between psychosocial stress and athletic injuries are suggested. More specifically, psychophysiological stressors (e.g. negative life-event stress, physical training) are suggested to influence the autonomic nervous system, which in turn influences recovery and behavioural mechanisms (e.g. decreased self-care and sleep quality) [20]. The changes in recovery and behavioural mechanisms may, in the next step, increase the risk for overuse injuries. Another multifactorial model discussing the aetiology of overuse injuries is the overtraining risks and outcomes model [22]. Within this model, the interactions between psychosocial, intra-personal, inter-personal and situational factors are suggested to influence the risk of imbalance between stress and recovery. Factors discussed in this model include super-motivation, pushing through injuries, relationships and behaviours of others related to injuries [22].

Psychosocial risk factors for traumatic injuries and overuse injuries in sport have previously been investigated. For example, athletes who experienced changes and a high level of stressful events were at a greater risk for sustaining a traumatic injury while no relation to overuse injuries was found [23, 24]. An empirical risk factor model [25, 26] that included psychosocial factors was suggested to influence an athlete’s stress response. An evaluation of the model showed that stress and a high stress response were related to an increased risk for injuries, but most of the included studies used time loss as the injury definition and very few studies separated overuse injuries and traumatic injuries [27]. Overuse injuries seldom result in time loss [11, 28] and are not adequately captured in these types of studies and evaluations.

Because of the prevalence of overuse injuries, it is of interest to explore psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries. Particularly, it is important to understand and explain why and how overuse injuries occur in line with the studies regarding psychosocial risk factors for traumatic injuries. With that knowledge, effective prevention programmes can be developed, implemented and evaluated. The aim of this study was to systematically review studies examining psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries in competitive athletes.

2 Methods

For conducting and reporting this systematic review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [29], see Appendices 1 and 2 of the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). The study protocol was prospectively registered (PROSPERO ID: CRD42019123580).

2.1 Definitions and Outcome

Overuse injury was defined as an injury occurring without an identified inciting event [10, 30]. The risk factors were psychosocial factors that were identified to influence the risk for the occurrence of overuse injury.

2.2 Literature Search Strategy

Medline (Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection and PsycINFO (Ovid) were searched from inception to July 2021. Hand searching of journals and reference checking were also performed by the authors.

The following keywords were used together with other related words, and with appropriate truncations and Boolean combinations of words and operators: “overuse injury” AND “sport” AND “psychology” AND “risk factor” limited to academic peer-reviewed journals in Swedish, English, German, Spanish and French. A complete search was performed by librarians at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden after several test searches. See Appendix 3 of the ESM for a full documentation.

2.3 Eligibility Criteria/Selection Criteria

Studies reporting psychological or psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries in athletes published in academic peer-reviewed journals in the above-mentioned languages until July 2021 were eligible for quality assessment. Eligible studies had to include competitive athletes as a population. Studies where the outcome was not clearly stated, or where overuse injuries were pooled with other injuries (e.g. traumatic or chronic injuries), were excluded.

Published papers without empirical data, not presenting results about overuse injuries or not assessing psychosocial factors, were excluded as well as duplicates. Articles assessing psychosocial factors as an outcome after overuse injury were also excluded.

2.4 Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias was evaluated using a modified Risk of Bias Assessment tool for Non-randomized Studies, RoBANS [31], i.e. items specific to overuse injuries and “psychological factors” were included (see Appendix 4A of the ESM for a full description). RoBANS is a six-item tool for assessing selection bias of participants and confounding variables, misclassifications bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and analysis in non-randomised studies. For each item, a low, unclear or high risk of bias was evaluated according to the specified criteria [31]. For assessment of qualitative studies, we used the “Quality assessment scale for qualitative studies” by the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services [32] (see Appendix 4B of the ESM for a full description). These two assessment tools are frequently used and were chosen with the assumption that most of the included articles would be non-randomised and qualitative studies.

2.5 Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two of the authors (UT, SM) independently screened and extracted the articles by title and abstract using an online screening tool, Rayyan [33]. The remaining articles were assessed in full text and the quality and bias were evaluated by the two first authors using the assessment tools. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus or by involving the third author (AI).

A decision not to perform a meta-analysis was taken after pilot searches revealed substantial methodological and clinical heterogeneity between studies. Instead, data from both quantitative and qualitative studies were synthesised and reported according to the narrative synthesis approach, commonly referred to as the best approach to “tell the story” of the findings from a wide range of research designs [34] and categorised into three areas: intra-personal and inter-personal and sociocultural factors. We reported effect sizes (specified in-text) when available in quantitative studies.

3 Results

3.1 Literature Identification

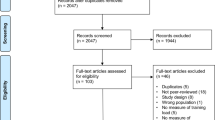

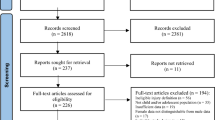

Systematic database searching yielded a total of 6890 records, and a further 11 studies were identified through other sources (e.g. citation searching). Following deletion of duplicates, a first screening based on title and abstract resulted in selection of 26 eligible articles. Full-text articles were subsequently obtained and assessed against eligibility criteria (see Appendix 5 of the ESM for full references and reasons for exclusion), leaving 14 articles included for a full review and synthesis. Nine studies reported quantitative associations between psychosocial factors and overuse injury, while five studies reported qualitative findings. For an overview of the screening process, see Fig. 1.

3.2 Study Characteristics

The 14 studies included data from 1061 athletes with a mean age of 25.9 years, of whom 589 (56%) were female and 472 (44%) were male. The competitive level ranged from regional to international. The 14 studies covered a wide variety of individual and team sports. See Table 1 for a detailed description of the study and sample characteristics.

3.3 Measures

In total, 27 psychosocial factors were identified. Of those, 17 factors were highlighted in the quantitative studies using 26 different measures (see Table 1). Two studies reported on the development of new scales to measure psychosocial factors (competitiveness and hyperactivity) [37, 40]. All studies reported information about psychometric properties of the psychosocial measures used, for which internal consistency ranged from acceptable (0.7 ≤ α < 0.8) to excellent (0.9 ≤ α). All studies used single timepoint measures of psychosocial variables (e.g. as baseline measures in prospective studies), except for the study of van der Does et al. [41] in which perceived stress and recovery were measured every 3 weeks.

Methods for measuring overuse injuries also varied between studies (see Table 1), mostly because of the different definitions and diagnosis methods used. Ten studies used self-reported measures [35, 36, 38,39,40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48], including a subsequent diagnosis confirmation by medical professionals for six of them [35, 38, 39, 42, 43, 48], whereas three studies used medical attention as a condition for diagnosis of an overuse injury [37, 41, 47]. One study referred to the time-loss definition [39], while four studies clearly mentioned the use of a functional definition [38, 40, 42, 43]. The two studies of Van der Sluis et al. were conducted on the same sample [42, 43].

3.4 Quantitative Studies

3.4.1 Psychosocial Factors

The 17 psychosocial factors identified in the nine quantitative studies were clustered into three different categories: intra-personal factors, inter-personal factors and sociocultural factors.

3.4.1.1 Intra-Personal Factors

Fourteen intra-personal factors were examined in the included quantitative studies: motivation/competitiveness, exercise dependency, athletic identity, perceived stress from sport and life, type A behaviour, perfectionism, risk taking, coping skills, personality traits, attentional focus, locus of control, gender typing, metacognitive skills of self-regulation, and body consciousness and hyperactivity.

Athletes having reported an overuse injury scored higher in competitive and goal-oriented motivation in comparison to their counterparts [36]. However, the level of competitiveness could not be used to discriminate between athletes with and without overuse injury [37]. Female athletes with an overuse injury scored as high, or higher, than athletes without overuse injury on a number of subscales measuring motivation for exercise, namely: weight management, physical health, stress-mood, skill development, fun-enjoyment, socialising and muscle improvement [37]. However, none of these differences was statistically significant, and these differences were not observed in men. Exercise dependency was found to be associated with overuse injury risk in marathon runners [36], and in female long-distance runners [37], but not in elite track and field athletes [40]. The combination of competitive motivation, goal-oriented motivation and exercise dependency increased the risk for overuse injuries [36]. Athletes categorised in the group with the highest risk for overuse injuries were characterised by a higher level of athletic identity in comparison to athletes in the other two groups, who reported fewer overuse injuries [38].

No significant differences were found between athletes who sustained overuse injuries and uninjured athletes regarding absolute perceived stress and recovery [41]. However, a decrease in perceived personal accomplishment in sport over 3 weeks of training increased the risk of sustaining an overuse injury during the following period (OR = 0.59) [41]. One study showed that perceived negative life event stress was the main variable allowing discrimination between athletes in a psychosocial risk profile for overuse injuries (who presented with elevated stress values) and athletes in the other profiles who were less prone to negative life event stress and who sustained fewer overuse injuries [38]. Female athletes with a previous overuse injury were found to score significantly higher than the other women for overall type A behaviour and for the sub-dimension time pressure [37]. Athletes in a psychosocial risk profile for overuse injuries were characterised by higher values for perfectionistic concerns than athletes in the other profiles, whereas perfectionistic strivings did not contribute to discriminating at-risk athletes for overuse injury [38]. In young male athletes, risk taking explained 15% of the variance in time-loss overuse injuries and 13% of the variance in overuse severity scores [42]. The maladaptive coping behaviour of self-blame was found to be associated with an increased risk of overuse injury in athletes [40].

Athletes who reported an overuse injury scored higher values for vigilance (Cohen’s d = 1.003), privateness (d = 0.758) and self-reliance (d = 0.943) and lower values for dominance (d = 0.716), rule consciousness (d = 0.944) and overall self-control (d = 1.178) in comparison to injury-free athletes [35]. No differences were found for the other ten personality traits that were measured in this study [35]. Regarding their attentional focus, athletes who sustained an overuse injury had a significantly higher preference for association with internal physiological sensations while training (as opposed to dissociation) than athletes without overuse injury [36], but not when attentional focus was considered as a potential mediator between motivational variables and injury [36]. Locus of control did not discriminate between athletes with and without overuse injury [37]. No statistically significant differences were found between athletes with a previous overuse injury and injury-free athletes for any of the attributes (i.e. instrumentality, expressiveness and social desirability) that are used to define individuals’ gender typing [37]. In another study, a lack of self-monitoring skills was found to be associated with a higher category of time-loss overuse injuries (odds ratio = 4.555). This was particularly the case in girls (odds ratio = 10.757), but not in boys [43]. In addition, the reflection score significantly predicted overuse injury severity score along with exposure time (R2 = 0.201) [43]. The other two meta-cognitive skills, planning and evaluation, were not related to the risk of overuse injury [43]. No differences were found in overuse injury risk among athletes regarding body consciousness and hyperactivity used as a combined variable [40].

3.4.1.2 Inter-Personal Factors

Two inter-personal factors were identified in the quantitative studies: coach-athlete relationship and inter-personal stressors. Athletes categorised into the psychosocial risk profile for overuse injuries reported having a relatively poor relationship with their coach, in comparison with the other profiles [38]. Athletes reporting their coach as a source of stress were found to be at greater risk of sustaining an overuse injury (odds ratio = 1.21) [39]. In this study, none of the other inter-personal stressors investigated (teammates and friends) was associated with overuse injury risk [39].

3.4.1.3 Sociocultural Factors

A single sociocultural factor was investigated in the quantitative studies: perceived motivational climate. This factor assesses the athletes’ perceptions of the motivational climate within their teams using an ego-oriented climate and a task-oriented climate. None of the two variables of perceived motivational climate, ego-oriented climate and task-oriented climate, was found to be associated with the risk of overuse injury [39, 40].

3.4.2 Assessment of Risk of Bias

The results of the assessment of risk of bias for quantitative studies are presented in Table 2. One of the nine studies was rated as having a low risk of bias [37], four had an unclear risk of bias for some items, [38,39,40, 42], whereas the other four studies were allocated a high risk of bias for at least one item [35, 36, 41, 43].

3.5 Qualitative Studies

3.5.1 Psychosocial Factors

Sixteen psychosocial factors were identified in the five qualitative studies and were classified in the same three categories as we used for the classification of variables from the quantitative studies: intra-personal factors, inter-personal factors and sociocultural factors.

3.5.1.1 Intra-Personal Factors

Nine intra-personal factors were examined in the identified qualitative studies: motivation/competitiveness, athletic identity, passion/dedication, excessive training, neglecting warnings signals and long-term consequences, acceptance of pain/decreased function, perceived stress from sport and life, previous injuries and coping skills.

Having set a clear goal corresponding to the date of a competition was described as predisposing athletes to overuse injuries [46]. A strong athletic identity characterised athletes having sustained an overuse injury in one qualitative study [47]. Passion and dedication to their sport were also reported as risk factors predisposing athletes to overuse injuries in three different studies [44, 47, 48]. Excessive training [47, 48] as well as training despite being mentally and/or physically tired [47], were described as behaviours increasing the risk for overuse injuries. A range of cognitive interpretations that followed the perception of the gradual overuse symptoms were described as psychosocial mechanisms resulting in more severe or prolonged overuse injury episodes [45, 47, 48]. In the early stages of overuse injuries, athletes expressed that they ignored the bodily warning signals and neglected the possible negative long-term consequences of training despite these symptoms [47, 48]. In the following stages, athletes’ thought patterns included ‘magical thinking’, meaning that the problem will resolve by itself without having to change their training behaviours [45]. In the late stages of overuse injuries, athletes were found to accept the pain and decreased function associated with the injury and to continue training and competing, unless the pain had increased to an intolerable level or if strong recommendations were received from medical professionals or coaches to adapt their training [45, 47]. The common thread in these cognitive interpretations was that they all allowed the athletes to avoid resting.

Sport-specific stressors (e.g. insecure position in the team) and non-sport stressors (e.g. stress from work or school) were also reported as risk factors for overuse injuries [47, 48]. In addition, a lack of recovery emerged as a common risk factor in one study [47]. Putting too much pressure on oneself was a personal stressor identified as a risk factor in two qualitative studies [47, 48]. Having sustained previous injuries was also described by athletes as a risk factor for subsequent overuse injuries, in the sense that they were aware of what recognising themselves as injured again would mean in terms of absence from training, low self-efficacy and negative emotions associated with the rehabilitation period [47]. These athletes therefore preferred not to consider their overuse symptoms as reflecting an injury, a reasoning that is likely to result in a more serious overuse injury [47]. Athletes having sustained an overuse injury reported a lack of adaptive skills to cope with pressure and fear [47, 48], and to handle physical complaints [47].

3.5.1.2 Inter-Personal Factors

Five inter-personal factors were identified in the qualitative studies: coach-athlete relationship, communication, internal rivalry, inter-personal stressors and social support. A poor coach-athlete relationship was perceived as a contributing factor to overuse injuries in one study [48]. Additionally, good relationships may also be linked to an increased risk of overuse injury as participants reported their sense of duty towards a coach (or team) as a potential risk factor [48]. Poor communication between athletes and their coaches, or a misalignment between different coaches, was suggested to increase the risk of overuse injury by creating misperceptions and by encouraging athletes not to disclose their early symptoms [44, 47, 48]. Internal rivalry was also expressed as contributing to the onset of overuse injuries [47, 48]. Inter-personal stressors involving other individuals (i.e. the club’s president, coaches, teammates and the audience) were also reported as factors that contributed to the onset of overuse injuries [44, 47]. The overall lack of social support from family, friends and teammates, as well as the specific lack of social support from coaches and medical staff when facing an overuse injury were also reported by these athletes [47].

3.5.1.3 Sociocultural Factors

Two sociocultural factors were identified in the qualitative studies: pain normalisation and the belief that overuse injuries are less important than traumatic injuries. Pain normalisation was described as the core feature of a ‘culture of risk’, which is associated with a low acceptance of complaining [44, 47]. These athletes were described as ensuring their cultural embodiment by showing their adherence to the social values of their club (e.g. sporting success, striving for perfection) through ‘mentally tough’ attitudes and behaviours. This meant accepting pain as an integral part of sport and continuing to train and compete despite experiencing pain, which ultimately resulted in overuse injuries [44]. The social norm that overuse injuries are less important than traumatic injuries and do not necessitate serious consideration was also apparent in three qualitative studies conducted in different contexts [44, 47, 48].

3.5.2 Assessment of Risk of Bias

The results of the risk of bias assessment for qualitative studies are presented in Table 3. One study was rated as having a low risk of bias [47]. Three of the five studies were rated as having an unclear risk of bias for two items [44,45,46], whereas the remaining study was allocated a high risk of bias for one item [48].

3.6 Meta-Synthesis: Summary of the Findings

A meta-synthesis table summarising the findings of both quantitative and qualitative studies and providing an overview of the certainty of evidence for each factor is presented in Table 4.

4 Discussion

The aim of this review was to systematically identify psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries in competitive athletes. Overall, we identified nine quantitative and five qualitative studies with a focus on 27 psychosocial risk factors for overuse injury in various sports and athletic levels. Based on the results from these studies, we suggest that a number of intra-personal, inter-personal and sociocultural factors might influence the risk of overuse injuries and should, therefore, be considered in sports burdened by overuse injuries. However, the certainty of evidence around the psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries remains small in comparison to the evidence for traumatic injuries. Consequently, the preliminary findings presented in this review may provide grounds for further exploration of these potential risk factors.

Importantly, the relatively high risk of bias identified in a majority of the included studies should be considered when interpreting and using the present findings. There are several aspects that are important to highlight in relation to this issue. First, regarding the certainty of evidence of the psychosocial factors identified, it should be noted that some variables were only investigated in single studies (see Table 4). Second, an important aspect in relation to the strength of evidence is the heterogeneity of the overuse injury definitions and recording methods used in the included studies. However, most of them (10 out of 14) used the recommended self-reported method [65], and only one study referred to the time-loss definition that should be avoided [65]. Third, the athletic level may be a potential confounding factor when examining the risk of overuse injury. While studies dealing with recreational-level athletes were excluded, this review covered a wide range of competitive levels (from regional to international), which should be considered when interpreting the present findings. However, the potential risk factors identified in our study (e.g. passion, athletic identity) suggest that the level of investment in the sport of athletes might be more important than their absolute level of performance in relation to overuse injuries. Consequently, attention should be directed towards athletes of all levels who may be equally susceptible to overuse injuries. Moreover, some of the factors identified such as sociocultural factors (e.g. pain normalisation) are likely to be sport dependent.

Despite the uncertainty of the evidence, the results of the included studies indicate that psychosocial factors might increase the risk of overuse injuries. More specifically, psychosocial stress, whether involving intra-personal or inter-personal stressors, appeared to be one of the most prominent factors identified in the current review [38, 39, 41, 44, 47, 48]. Athletes exposed to psychosocial stress may be more susceptible to overuse injuries through the synergetic effects of psychosocial and physical stress [20, 49]. This hypothesis is supported by previous research indicating that athletes’ adaptation to intense training is impaired by psychosocial stress [21, 50] and concordant with the primary tenet of the biopsychosocial model of stress and athletic injury and health [20]. More specifically, emotional, behavioural and physiological factors should be considered as potential mechanisms mediating the relationship between psychosocial stress and overuse injuries [20]. Indeed, overuse injuries are considered to be a response at the cellular level of repetitive overload at the systemic level [51], and chronic exposure to psychosocial stressors might contribute to this systemic overload through immune and hormonal patterns [20, 49]. Cognitive features are also known to exacerbate or prolong emotional reactivity to a stressor and the concomitant physiological response [20]. Subsequently, individuals may gradually accommodate to their overuse injury because the initially prominent affective reaction becomes weaker and receives decreased attention [45, 56], and the affected individuals therefore progressively accept their impaired function [45, 47].

In line with a complex approach to sport injury [52], the other intra-personal factors identified in this review, such as perfectionism or coping skills, are likely to interact with the identified inter-personal (e.g. communication) and sociocultural (e.g. pain normalisation) risk factors to influence the risk of overuse injury. For example, previous findings indicate that individuals with elevated perfectionistic concerns are more likely to experience chronic psychosocial stress [54, 55], thus leading to a higher risk of sustaining athletic injuries [53], which is consistent with our results. Athletes may also cope differently when experiencing physical complaints depending on certain dimensions of perfectionism [57], which may influence the development of an overuse injury. Furthermore, athletes presenting with a high athletic identity or goal-oriented motivation were suggested to be less flexible in their training because the frustration associated with having to rest may overshadow the negative emotions associated with the first signs of a developing overuse injury [37]. The inter-personal factors identified in the current review may reinforce this pattern. Poor communication and/or relationships between athletes and coaches may, for example, encourage athletes to under-report pain and early symptoms to avoid a conflict [39, 44]. The current review also found sociocultural risk factors for overuse injuries such as displaying ‘mentally tough’ attitudes and behaviours [44], which is congruent with theoretical models such as the biopsychosocial sport injury risk profile [58] and contributes to explaining why athletes with overuse injuries often delay the decision to rest and seek medical attention despite substantial impairment of performance and training capacities [11, 59].

4.1 Practical Implications

With respect to practical recommendations, as psychosocial stress may act in synergy with physiological stress to increase the risk of overuse injuries [20, 49], coaches and clinicians should consider using broad subjective measures aiming to monitor the athletes’ response to both training and non-training (i.e. psychosocial) stressors [60]. This could be done, for example, on a daily or weekly basis using self-reported measures. Examples of such tools include the Recovery Stress Questionnaire for Athletes (RESTQ-S) [61] and the Multi-Component Training Distress Scale (MTDS) [62]. Importantly, as psychosocial stress seems of be a common antecedent of traumatic [27] and overuse injuries, these monitoring tools, as well as psychological interventions targeting stress responses (e.g. mindfulness-based programmes [63]) might be implemented to prevent both types of injuries. We encourage coaches for which these measures might not be affordable to introduce communication routines with their athletes on a daily basis, for example by taking a few minutes at the beginning of every new training session to discuss their level of recovery and experience of potential stressors, and to adjust the training content accordingly if necessary. Finally, sport psychology practitioners are encouraged to promote an athlete’s multidimensional sense of self and a sustainable narrative that continues despite fluctuations in form, performance and potential injuries [64].

4.2 Strengths and Limitations

One of the strengths of the current review is that the literature search was performed by experienced librarians using a thorough strategy. In addition, the risk of bias in the included studies was carefully assessed using validated tools that were modified to account for the objective of this review (i.e. items specific to overuse injury measurement were added). One potential limitation is the relatively small number of included studies. Additional limitations are the heterogeneity in terms of study designs and methods used to measure psychosocial factors and overuse injury, which made the overall certainty of evidence for each factor difficult to appraise. Additionally, a majority of the studies had an unclear or high risk of bias on at least one item. One of the main reasons for the high scores in potential for bias was the use of “intra-personal” means (i.e. self-reported perceptions of the factors) when assessing the “inter-personal factors” and “sociocultural factors”. These issues are especially important to consider when interpreting the findings of this review. Lastly, this review focused on competitive athletes. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised to other populations such as recreational athletes or dancers without caution.

4.3 Future Research Directions

From a methodological standpoint, future research is recommended to more strictly adhere to the recommendations that have been formulated regarding overuse injury definition and recording methods [65]. Regarding the gradual pattern of onset of overuse injuries, intensive repeated-measure designs with, for instance, weekly measurements of psychosocial stress and other potential risk factors, may allow the identification of their relationships with overuse symptoms over time [59, 66]. It is also important that future research investigates the complex processes involving the different psychosocial factors suggested in this review and their potential interactions with physiological mechanisms (e.g. repetitive overload) [51] that may better predict the risk of overuse injury. In this regard, non-linear and complex system paradigms should be considered [52, 67]. In addition, intervention studies aiming at preventing overuse injuries, using psychological techniques, could be designed based on the psychosocial factors identified in this review.

5 Conclusions

The findings of this review suggest that psychosocial factors are likely to influence the risk of overuse injuries in competitive athletes. Importantly, these factors and the mechanisms through which they may predispose athletes to overuse injuries appeared to be partially different to those extensively described for traumatic injuries [25,26,27]. When aiming to reduce the risk of overuse injuries from a psychosocial standpoint, coaches, supporting staff and sport psychologists are therefore encouraged to acknowledge the similarities and differences between traumatic and overuse injury aetiology and to implement preventive measures based on the psychosocial factors identified in this review.

References

Jacobsson J, et al. Injury patterns in Swedish elite athletics: annual incidence, injury types and risk factors. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(15):941–52.

Pluim BM, et al. A one-season prospective study of injuries and illness in elite junior tennis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(5):564–71.

Clarsen B, et al. The prevalence and impact of overuse injuries in five Norwegian sports: application of a new surveillance method. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(3):323–30.

Kerr ZY, et al. Epidemiology of National Collegiate Athletic Association men’s and women’s swimming and diving injuries from 2009/2010 to 2013/2014. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(7):465–71.

Clarsen B, et al. The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center questionnaire on health problems: a new approach to prospective monitoring of illness and injury in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(9):754–60.

Tranaeus U, et al. Injuries in Swedish floorball: a cost analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(5):508–13.

Huxley DJ, O’Connor D, Healey PA. An examination of the training profiles and injuries in elite youth track and field athletes. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14(2):185–92.

Drawer S, Fuller CW. Propensity for osteoarthritis and lower limb joint pain in retired professional soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(6):402–8.

Bahr R, Krosshaug T. Understanding injury mechanisms: a key component of preventing injuries in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(6):324–9.

Bahr R. No injuries, but plenty of pain? On the methodology for recording overuse symptoms in sports. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(13):966–72.

Yang JZ, et al. Epidemiology of overuse and acute injuries among competitive collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2012;47(2):198–204.

Timpka T, et al. Injury and illness definitions and data collection procedures for use in epidemiological studies in athletics (track and field): consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):483–90.

Taimela S, Kujala UM, Osterman K. Intrinsic risk factors and athletic injuries. Sports Med. 1990;9(4):205–15.

Fuller CW, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(3):193–201.

DiFiori JP, et al. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Med. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(4):287–8.

Windt J, Gabbett TJ. How do training and competition workloads relate to injury? The workload-injury aetiology model. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(5):428–35.

Kellmann M. Preventing overtraining in athletes in high-intensity sports and stress/recovery monitoring. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:95–102.

Meeuwisse WH, et al. A dynamic model of etiology in sport injury: the recursive nature of risk and causation. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(3):215–9.

Leppanen M, et al. Epidemiology of overuse injuries in youth team sports: a 3-year prospective study. Int J Sport Med. 2017;38(11):847–56.

Appaneal R, Perna F. Biopsychosocial model of injury. In: Eklund R, Tenenbaum G, editors. Encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2014. p. 74–7.

Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Bartholomew JB, Sinha R. Chronic psychological stress impairs recovery of muscular function and somatic sensations over a 96-hour period. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(7):2007–17.

Richardson SO, Andersen MB, Morris T. Overtraining athletes: personal journeys in sport. Human Kinetics; 2008.

Lysens R, Vanden Auweele Y, Ostyn M. The relationship between psychosocial factors and sports injuries. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1986;26(1):77–84.

Williams JM, Andersen MB. Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury and interventions for risk reduction. In: Tenenbaum G, Eklund R, editors. Handbook of sport psychology. New York: Wiley; 2007. p. 379–403.

Andersen MB, Williams JM. A model of stress and athletic injury: prediction and prevention. J Sports Sport Exerc. 1988;10(3):294–306.

Williams JM, Andersen MB. Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury: review and critique of the stress and injury model. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1998;10(1):5–25.

Ivarsson A, et al. Psychosocial factors and sport injuries: meta-analyses for prediction and prevention. Sports Med. 2017;47(2):353–65.

Clarsen B, Bahr R. Matching the choice of injury/illness definition to study setting, purpose and design: one size does not fit all! Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):510–2.

Page MJ, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103–12.

Roos KG, Marshall SW. Definition and usage of the term “overuse injury” in the US high school and collegiate sport epidemiology literature: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2014;44(3):405–21.

Kim SY, et al. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(4):408–14.

Assessment of methods in health care: a handbook. Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU). Stockholm; 2016.

Ouzzani M, et al. Rayyan: a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Popay J, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme. Version. 2006;1:b92.

Berengui R, et al. Personality and injuries in high performance sports. Rev Iberoam Psicol Ejerc El Deporte. 2017;12(1):15–22.

Christensen D, Ogle B. Injury description and prediction in marathon runners. Int J Sport Psychol. 2017;48(6):660–74.

Ekenman I, et al. Stress fractures of the tibia: can personality traits help us detect the injury-prone athlete? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001;11(2):87–95.

Martin S, et al. Psychological risk profile for overuse injuries in sport: an exploratory study. J Sport Sci. 2021;39(17):1926–35.

Pensgaard AM, et al. Psychosocial stress factors, including the relationship with the coach, and their influence on acute and overuse injury risk in elite female football players. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1):e000317.

Timpka T, et al. The psychological factor “self-blame” predicts overuse injury among top-level Swedish track and field athletes: a 12-month cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(22):1472–7.

van der Does HTD, et al. Injury risk is increased by changes in perceived recovery of team sport players. Clin J Sport Med. 2017;27(1):46–51.

Van der Sluis A, et al. Is risk-taking in talented junior tennis players related to overuse injuries? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(11):1347–55.

van der Sluis A, et al. Self-regulatory skills: are they helpful in the prevention of overuse injuries in talented tennis players? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019;29(7):1050–8.

Cavallerio F, Wadey R, Wagstaff CRD. Understanding overuse injuries in rhythmic gymnastics: a 12-month ethnographic study. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2016;25:100–9.

Jelvegard S, et al. Perception of health problems among competitive runners: a qualitative study of cognitive appraisals and behavioral responses. Orthopaed J Sports Med. 2016;4(12).

Russell HC, Wiese-Bjornstal DM. Narratives of psychosocial response to microtrauma injury among long-distance runners. Sports. 2015;3(3):159–77.

Tranaeus U, et al. Psychological antecedents of overuse injuries in Swedish elite floorball players. Athletic Insight. 2014;6(2):155–72.

van Wilgen CP, Verhagen E. A qualitative study on overuse injuries: the beliefs of athletes and coaches. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15(2):116–21.

Clow A, Hucklebridge F. The impact of psychological stress on immune function in the athletic population. Exerc immunol Rev. 2004;7:5–17.

Perna FM, et al. Cognitive behavioral stress management effects on injury and illness among competitive athletes: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25(1):66–73.

Fischer F, et al. Causes of overuse in sports, in prevention of injuries and overuse in sports. New York: Springer; 2016. p. 27–38.

Bittencourt N, et al. Complex systems approach for sports injuries: moving from risk factor identification to injury pattern recognition: narrative review and new concept. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(21):1309–14.

Madigan DJ, et al. Perfectionism predicts injury in junior athletes: preliminary evidence from a prospective study. J Sports Sci. 2018;36(5):545–50.

Dunkley DM, Solomon-Krakus S, Moroz M. Personal standards and self-critical perfectionism and distress: stress, coping, and perceived social support as mediators and moderators. In: Perfectionism, health, and well-being. New York: Springer; 2016. p. 157–76.

Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism and stress processes in psychopathology. In: Flett GL, Hewitt PL, editors. Perfectionism: theory, research, and treatment. New York: American Psychological Association; 2002. p. 255–84.

Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. Explaining away: a model of affective adaptation. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(5):370–86.

Jowett GE, Hill AP, Forsdyke D, Gledhill A. Perfectionism and coping with injury in marathon runners: a test of the 2×2 model of perfectionism. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2018;37:26–32.

Wiese-Bjornstal DM. Psychology and socioculture affect injury risk, response, and recovery in high-intensity athletes: a consensus statement: sport injury psychology consensus statement. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:103–11.

Clarsen B, Myklebust G, Bahr R. Development and validation of a new method for the registration of overuse injuries in sports injury epidemiology: the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) overuse injury questionnaire. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(8):495–502.

Saw AE, Main LC, Gastin PB. Monitoring the athlete training response: subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(5):281–91.

Kellmann M, Kölling S. Recovery and stress in sport: a manual for testing and assessment. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge; 2019.

Main L, Grove JR. A multi-component assessment model for monitoring training distress among athletes. Eur J Sport Sci. 2009;9(4):195–202.

Ivarsson A, et al. It pays to pay attention: a mindfulness-based program for injury prevention with soccer players. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2015;27(3):319–34.

Everard C, Wadey R, Howells K. Storying sports injury experiences of elite track athletes: a narrative analysis. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2021;56:102007.

Bahr R, et al. International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement: methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sports 2020 (including the STROBE Extension for Sports Injury and Illness Surveillance (STROBE-SIIS)). Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(2):2325967120902908.

Johnson U, Ivarsson A. Psychosocial factors and sport injuries: prediction, prevention and future research directions. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;16:89–92.

Balagué N, et al. Sport science integration: an evolutionary synthesis. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(1):51–62.

Acknowledgements

We thank Carl Gornitzki and Sabina Gillsund at Karolinska Institutet’s Library, Stockholm, Sweden, who suggested search strategies, conducted searches and retrieved articles that may have included psychosocial risk factors for overuse injuries in athletes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences (GIH).

Conflict of Interest

Ulrika Tranaeus, Simon Martin and Andreas Ivarsson declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this review.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Evaluation sheets are available upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Ulrika Tranæus and Simon Martin contributed equally during all phases and share first authorship. Andreas Ivarsson contributed to the method and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tranaeus, U., Martin, S. & Ivarsson, A. Psychosocial Risk Factors for Overuse Injuries in Competitive Athletes: A Mixed-Studies Systematic Review. Sports Med 52, 773–788 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01597-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01597-5