Abstract

A loss of physical functioning (i.e., a low physical capacity and/or a low physical activity) is a common feature in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). To date, the primary care physiotherapy and specialized pulmonary rehabilitation are clearly underused, and limited to patients with a moderate to very severe degree of airflow limitation (GOLD stage 2 or higher). However, improved referral rates are a necessity to lower the burden for patients with COPD and for society. Therefore, a multidisciplinary group of healthcare professionals and scientists proposes a new model for referral of patients with COPD to the right type of exercise-based care, irrespective of the degree of airflow limitation. Indeed, disease instability (recent hospitalization, yes/no), the burden of disease (no/low, mild/moderate or high), physical capacity (low or preserved) and physical activity (low or preserved) need to be used to allocate patients to one of the six distinct patient profiles. Patients with profile 1 or 2 will not be referred for physiotherapy; patients with profiles 3–5 will be referred for primary care physiotherapy; and patients with profile 6 will be referred for screening for specialized pulmonary rehabilitation. The proposed Dutch model has the intention to get the right patient with COPD allocated to the right type of exercise-based care and at the right moment.

Similar content being viewed by others

To date, use of primary care physiotherapy or specialized pulmonary rehabilitation programs is very limited in patients with COPD (5.0 and 0.2%, respectively), while a larger proportion of these patients clearly qualify for this type of care. |

The current organization of Dutch healthcare needs to make a transition towards an adequate referral of patients with COPD to the different types of exercise-based care, including a healthy lifestyle advise, physiotherapy and/or specialized pulmonary rehabilitation programs. |

Disease stability, disease burden, physical capacity and physical activity are important traits to get the right patient allocated to the right type of exercise-related care and at the right moment, irrespective of the degree of airflow limitation. |

1 Introduction

Despite medical treatment by the general practitioner, an impaired physical, emotional and/or social functioning has been frequently reported in Dutch primary care patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [1,2,3]. These abnormalities can co-occur in different combinations, regardless of the degree of airflow limitation. Similar findings have been reported in patients with COPD who were under the care of Dutch pulmonologists [4, 5].

A loss of physical functioning (i.e., a low physical capacity and/or a low physical activity) is a common feature in patients with COPD [3, 6, 7]. Exercise-based interventions (combined with self-management education) and/or physical activity coaching programs can result in clinically relevant improvements in daily symptom burden, physical capacity, physical activity and health status compared to usual care in patients with COPD [8]. An interdisciplinary comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) program is defined as ‘a comprehensive intervention based on a thorough patient assessment followed by patient-tailored therapies, which include, but are not limited to, exercise training, education, and behavior change, designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory disease and to promote the long-term adherence of health-enhancing behaviors’ [9]. Such programs have shown to also improve the performance of activities of daily living, to increase self-efficacy, and to lower the degree of care dependency and healthcare utilization [5, 10,11,12,13,14] in COPD patients with a combination of physical, emotional and/or social treatable traits. Even though safety and efficacy of these interventions are clear, referral by physicians remains poor [15].

2 Current Clinical Practice

Current guidelines state that the degree of clinical complexity should determine the types of (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) interventions provided, ranging from healthy lifestyle advise combined with recommended drug therapy [16, 17], up to a comprehensive, inpatient, interdisciplinary PR program for patients with multiple physical, emotional and/or social treatable traits at the time of referral [10, 18].

Since January 2019, patients with COPD in the Netherlands are entitled to reimbursement of the costs of physiotherapy (or exercise therapy Cesar/Mensendieck) provided in the primary care setting via the basic national healthcare insurance [19]. Indeed, the National Healthcare Institute advised the Dutch Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport that patients with moderate to very severe COPD (FEV1 < 80% predicted) are eligible to receive a maximum number of reimbursed physiotherapy sessions in the first 12 months of treatment and during the enduring maintenance phase. However, GOLD C/D patients who suffer from a new exacerbation during/after treatment are not entitled to reimbursement of the costs of extra physiotherapy sessions. Moreover, the maximum number of sessions is solely based on the GOLD ABCD classification at the time of referral, and excludes GOLD 1 patients (Table 1). However, a subgroup of GOLD 1 patients can suffer from an impaired physical functioning [3], which justifies early referral to exercise-related care, such as physiotherapy [20]. Also respiratory symptom burden and exacerbation history (the two attributes required to classify patients into GOLD ABCD) have not been validated to identify the right candidates for the right type of exercise-based care in patients with COPD. Consequently, highly-symptomatic GOLD B patients are currently entitled to a lower maximum number of reimbursed physiotherapy sessions than the no/low-symptomatic GOLD C patients (Table 1). Moreover, potentially important targets for physiotherapy, such as exercise intolerance and physical inactivity, are ignored in current Dutch referral rules, but vary to a great extent in the different GOLD groups and cannot be derived truthfully from the total scores of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) or COPD Assessment Test (CAT), the questionnaires that are used to qualify patients as GOLD A/C or B/D [21]. Finally, a large variation in treatable traits is present within specific GOLD groups [22]. This necessitates additional assessment of the physical, emotional and social status of patients with COPD to truly understand the disease burden, and to put together a patient-tailored treatment program, including exercise-based care.

3 The 2020 Dutch Model

An ad hoc Task Force, including experts in the field of physiotherapy, exercise therapy (Cesar and Mensendieck), rehabilitation sciences, respiratory medicine, general medicine, elderly care medicine and patient representatives, put together an alternative practice- and experience-based proposal (Fig. 1). This newly proposed flowchart includes an initial patient profiling at the office of the general practitioner or pulmonologist, using a short and simple questionnaire (CCQ or CAT, which both go beyond respiratory symptoms [23, 24]) to determine the degree of disease burden [24, 25]. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale is not proposed as initial screening tool, as its focus is too limited to truthfully capture the multidimensional symptoms/limitations of patients with COPD [23, 27].

Flowchart for exercise-based care for patients with COPD. CCQ Clinical COPD Questionnaire, CAT COPD Assessment Test, % % predicted value, st/d steps per day. *During hospital admission patients with COPD should be offered exercise-based physiotherapy in addition to regular respiratory physiotherapy [58]. ‡Frail patients with COPD in the palliative phase of the disease, those who are on the waiting list for lung transplantation, those who are on long-term oxygen therapy, those who are on non-invasive ventilation, and/or those with comorbidities which seriously affect physical capacity/activity. †Patients who are willing to pay out of pocket. Gray area: two 1-h pre-treatment screening sessions to do an intake, and to assess physical capacity and physical activity (as described in the text). Patients who are do not enter a pulmonary rehabilitation program after the screening, will be referred for exercise-based primary care, according to the described profiling 2–5

3.1 No-to-Low Disease Burden

Patients with no-to-low self-reported disease burden (CCQ < 1.0 point; CAT < 10 points [26]) will most probably have no clearly defined exercise-related treatment goal for which they need advice/supervision from a healthcare professional. Therefore, the general practitioner will provide these patients with healthy lifestyle advice, including an advice to remain regularly physically active [17]. However, there will be no referral for additional physiotherapy or PR (Fig. 1; patient profile 1). Once yearly or if a physician-treated exacerbation occurs earlier, the patient profiling re-starts from the top of Fig. 1.

3.2 Mild-to-Moderate Disease Burden

Patients with a mild-to-moderate self-reported burden of disease (CCQ 1.0–1.8 points; CAT 10–17 points [24]) will be referred to a physiotherapist (or exercise therapist Cesar/Mensendieck; in the primary or secondary care setting, with sufficient knowledge and skills in exercise-based care of patients with chronic lung diseases) to assess physical functioning during two screening visits. During the initial screening visit, patients will undergo an intake by the physiotherapist and a field-based exercise test, such as the 6-min walk test (6MWT) [28, 29]. Moreover, the patients will also receive a step counter/accelerometer, which will be returned at the second screening visit, 1 week later. During this second screening visit physical activity is evaluated and the 6MWT is repeated [30]. Patients with a rather preserved physical capacity (> 70% predicted value [3]) and physical activity (> 5000 steps per day [3]) will receive healthy lifestyle advice, but no additional professional allied healthcare (Fig. 1; patient profile 2). Once yearly or if a physician-treated exacerbation occurs earlier, the profiling re-starts from the top of Fig. 1. Patients with profiles 1 or 2 seem to be good candidates to participate in regular sports/walking activities as organized for elderly in the local communities, which stimulates regular walking in patients with COPD and their loved ones [31].

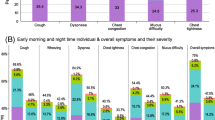

For patients with a mild-to-moderate self-reported disease burden, accompanied by an impaired physical function [low physical capacity (≤ 70% predicted value) and/or low physical activity (≤ 5000 steps per day)], intervention will start in the primary care physiotherapy setting (Fig. 1; patient profiles 3–5). In profile 3, the treatment will focus on physical activity coaching to increase the daily physical activity [32]; in profile 4, the treatment will focus on exercise training to increase the physical capacity [33, 34]; and in profile 5 it will be a combination thereof. As profile 5 patients have to increase their physical capacity and physical activity, it seems fair that they are entitled to the reimbursement of the costs of more physiotherapy sessions provided in the primary care setting compared to profile 3 or 4 patients (Table 2). The current reimbursement of primary care physiotherapy sessions for the GOLD D patients (Table 1) will suffice for the newly proposed model. In contrast, the number of reimbursed physiotherapy sessions for patients with COPD GOLD B needs to increase to enable the proposed model. It is hard to understand why GOLD D patients are entitled to a higher number of primary care physiotherapy sessions than GOLD B patients. Indeed, a secondary analysis of the data of Koolen et al. [3] shows no differences in physical capacity and physical activity between GOLD B or D patients after stratification for patient profiles 2 to 5 (Fig. 2). Obviously, respiratory physiotherapy, including mucus evacuation techniques, needs to be offered if indicated [35].

Data are derived from a secondary analysis of the data of Koolen et al. [3]

a Physical capacity in patients with COPD after stratification for patient profile (2–5) and GOLD group (B or D). b Physical activity in patients with COPD after stratification for patient profile (2–5) and GOLD group (B or D). 6MWD 6 min walk distance, GOLD Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Understandably, the aims of the individual patient and the success of treatment should determine the total number of physiotherapy sessions. If the treatment in the primary care setting fails, referral for a thorough assessment of underlying pathophysiological mechanisms as well as for screening for interdisciplinary PR should be discussed with the patient and referral physician. Possible unknown, common medical comorbidities [36] may cause this failure, and should be actively screened for [37]. Moreover, the lack of motivation and the lack of social support, may also, at least partially, explain failure of therapy [38].

If the physiotherapy is successful (i.e., patient’s goals have been achieved), participation in regular sports/walking activities as organized for elderly in the local communities [17] seems feasible and should be recommended in the maintenance phase. Follow up of the physical capacity and physical activity of these patients by the physiotherapist over time (for example, two evaluative sessions every 6 months) seems sensible and should be considered for reimbursement. If the physical capacity has declined > 45 m on the 6-min walk test and/or the physical activity is > 1500 steps/day lower compared to previous assessment (i.e., a decline which exceeds 1.5 times the known MCID), a re-start of the physiotherapy should be deliberated in consultation with the treating physician. If a physician-treated exacerbation occurs during follow up, the profiling re-starts from the top of Fig. 1.

3.3 High Disease Burden

Patients with COPD with a high self-reported disease burden (CCQ ≥ 1.9 points; CAT ≥ 18 points [24]), will be referred for a screening for PR. This is also proposed for patients who have recently been admitted to the hospital for an exacerbation, the so-called lung attack (Fig. 1; patient profile 6), as this is associated with significant deterioration of physical capacity, physical activity, and health status [39, 40]. Whether a patient should undergo a multidisciplinary PR program in secondary care, or a comprehensive, interdisciplinary, PR program in a Center of Expertise for Patients with Complex Chronic Lung Disease (tertiary care), depends on the degree of clinical complexity [18]. The clinical complexity may be operationalized by determining the number of treatable traits that is the number of potential targets for different rehabilitation ingredients [41, 42]. Obviously, also the interactions between treatable traits can also add to the clinical complexity, which is more challenging to operationalize [43]. As the degree of clinical complexity cannot be derived confidently from the degree of lung function impairment [4], a thorough pre-PR assessment has to determine the correct treatment allocation (Table 3). Patients with ≤ 2 treatable traits will be referred for an outpatient PR program in secondary care (outpatient, 8–12 weeks, three sessions per week, which will include physiotherapy and one or two other health disciplines, like health promotion and dietician; Fig. 1; patient profile 6A), while the remaining patients are appropriate candidates for a comprehensive, interdisciplinary PR program in a Centre of Expertise for Patients with Complex Chronic Lung Disease (specialized care; a minimum of 8 weeks, 3–5 PR days per week, with the possibility for inpatient stay), which will include physiotherapy, occupational therapy, dietary counseling, nutritional modulation, psychology, health promotion, enhanced art therapy, counseling by social work and respiratory nurse, respiratory medicine, and treatment of comorbidities (cardiology and internal medicine [18]; Fig. 1; patient profile 6B). Obviously, the inclusion criteria for treatment in a Centre of Expertise for Patients with Complex Chronic Lung Disease may change over time due to new insights. Indeed, cognitive functioning [44] and health literacy skills should be contemplated [45].

After completion of the PR program, including a structured outcome evaluation, the patients should be referred for at least once-weekly physiotherapy in the primary care setting to maintain the benefits in physical functioning and self-efficacy during the maintenance phase. To the future, E-health/M-health may also be put in place to coach and monitor patients during the enduring maintenance phase, which may stabilize physical capacity/activity levels, reduce in-person visits and may contribute to a better disease management [46, 47]. Robust evidence, however, is currently lacking [48].

4 Discussion

In The Netherlands, about 600,000 people are diagnosed with COPD [19]. As the burden to the patients as well as to society is clearly present [49], the current organization of Dutch healthcare needs to make a transition towards an adequate referral of these patients to the different types of exercise-based care, including a healthy lifestyle advise, physiotherapy and/or PR. We propose the abovementioned patient profiling as a basis for this allocation. This type of matched care starts in the physician’s office or during an exacerbation-related hospital admission. Therefore, systematically quantifying the degree of disease burden and a subsequent referral, according to Fig. 1, should be considered as a future key process indicator. Clearly, large differences exist between countries concerning organizational aspects and content of exercise-based care programs for patients with COPD [50]. These local circumstances, as well as patient’s preference, may affect the proposed flowchart.

To date, use of primary care physiotherapy or PR is estimated to be very limited in The Netherlands (5.0 and 0.2%, respectively), while a larger proportion of the patients with COPD clearly qualify for this type of care [3]. So, improved referral rates are a necessity to lower the disease burden for patients and society. The proposed Dutch model has the intention to get the right patient allocated to the right type of exercise-related care and at the right moment, irrespective of the degree of airflow limitation. This will also avoid unnecessary exercise-related care expenses for patients with no-to-low disease burden and a preserved physical capacity/activity.

References

Franssen FME, Smid DE, Deeg DJH, Huisman M, Poppelaars J, Wouters EFM, et al. The physical, mental, and social impact of COPD in a population-based sample: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2018;28(1):30.

Smid DE, Spruit MA, Houben-Wilke S, Muris JWM, Rohde GGU, Wouters EFM, et al. Burden of COPD in patients treated in different care settings in the Netherlands. Respir Med. 2016;118:76–83.

Koolen EH, van Hees HW, van Lummel RC, Dekhuijzen R, Djamin RS, Spruit MA, et al. "Can do" versus "do do": a novel concept to better understand physical functioning in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med. 2019;8(3):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030340.

Augustin IML, Spruit MA, Houben-Wilke S, Franssen FME, Vanfleteren L, Gaffron S, et al. The respiratory physiome: clustering based on a comprehensive lung function assessment in patients with COPD. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0201593.

Augustin IML, Wouters EFM, Houben-Wilke S, Gaffron S, Janssen DJA, Franssen FME, et al. Comprehensive lung function assessment does not allow to infer response to pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD. J Clin Med. 2018;8(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8010027.

Mesquita R, Spina G, Pitta F, Donaire-Gonzalez D, Deering BM, Patel MS, et al. Physical activity patterns and clusters in 1001 patients with COPD. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14(3):256–69.

Spruit MA, Watkins ML, Edwards LD, Vestbo J, Calverley PM, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Determinants of poor 6-min walking distance in patients with COPD: the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Med. 2010;104(6):849–57.

McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD003793. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3.

Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–64.

Spruit MA, Augustin IM, Vanfleteren LE, Janssen DJ, Gaffron S, Pennings HJ, et al. Differential response to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: multidimensional profiling. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(6):1625–35.

Vaes AW, Delbressine JML, Mesquita R, Goertz YMJ, Janssen DJA, Nakken N, et al. Impact of pulmonary rehabilitation on activities of daily living in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2019;126(3):607–15.

van Ranst D, Otten H, Meijer JW, van't Hul AJ. Outcome of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients with severely impaired health status. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:647–57.

Griffiths TL, Burr ML, Campbell IA, Lewis-Jenkins V, Mullins J, Shiels K, et al. Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9201):362–8.

Janssen DJ, Wilke S, Smid DE, Franssen FM, Augustin IM, Wouters EF, et al. Relationship between pulmonary rehabilitation and care dependency in COPD. Thorax. 2016;71(11):1054–6.

Spitzer KA, Stefan MS, Priya A, Pack QR, Pekow PS, Lagu T, et al. Participation in pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among medicare beneficiaries. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(1):99–106.

Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report: GOLD executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3):1700214. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00214-2017.

Frei A, Dalla Lana K, Radtke T, Stone E, Knopfli N, Puhan MA. A novel approach to increase physical activity in older adults in the community using citizen science: a mixed-methods study. Int J Public Health. 2019;64(5):669–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01230-3.

Spruit MA, Wouters EFM. Organizational aspects of pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic respiratory diseases. Respirology. 2019;24(9):838–843. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13512.

Fastenau A, Muris JW, de Bie RA, Hendriks EJ, Asijee GM, Beekman E, et al. Efficacy of a physical exercise training programme COPD in primary care: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:788.

Demeyer H, Duenas-Espin I, De Jong C, Louvaris Z, Hornikx M, Gimeno-Santos E, et al. Can health status questionnaires be used as a measure of physical activity in COPD patients? Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1565–8.

Sillen MJ, Franssen FM, Delbressine JM, Uszko-Lencer NH, Vanfleteren LE, Rutten EP, et al. Heterogeneity in clinical characteristics and co-morbidities in dyspneic individuals with COPD GOLD D: findings of the DICES trial. Respir Med. 2013;107(8):1186–94.

Houben-Wilke S, Janssen DJA, Franssen FME, Vanfleteren L, Wouters EFM, Spruit MA. Contribution of individual COPD assessment test (CAT) items to CAT total score and effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on CAT scores. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):205.

Smid DE, Franssen FME, Gonik M, Miravitlles M, Casanova C, Cosio BG, et al. Redefining cut-points for high symptom burden of the global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease classification in 18,577 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(12):1097 (e11–e24).

Ringbaek T, Martinez G, Lange P. A comparison of the assessment of quality of life with CAT, CCQ, and SGRQ in COPD patients participating in pulmonary rehabilitation. COPD. 2012;9(1):12–5.

Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report: GOLD executive summary. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(3):128–49.

Houben-Wilke S, Augustin IM, Vercoulen JH, van Ranst D, Bij de Vaate E, Wempe JB, et al. COPD stands for complex obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(148):180027. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0027-2018.

Singh SJ, Puhan MA, Andrianopoulos V, Hernandes NA, Mitchell KE, Hill CJ, et al. An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1447–788.

Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, Puhan MA, Pepin V, Saey D, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1428–46.

Hernandes NA, Wouters EF, Meijer K, Annegarn J, Pitta F, Spruit MA. Reproducibility of 6-minute walking test in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(2):261–7.

Mesquita R, Nakken N, Janssen DJA, van den Bogaart EHA, Delbressine JML, Essers JMN, et al. Activity levels and exercise motivation in patients with COPD and their resident loved ones. Chest. 2017;151(5):1028–38.

Altenburg WA, ten Hacken NH, Bossenbroek L, Kerstjens HA, de Greef MH, Wempe JB. Short- and long-term effects of a physical activity counselling programme in COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):112–21.

Spruit MA, Burtin C, De Boever P, Langer D, Vogiatzis I, Wouters EF, et al. COPD and exercise: does it make a difference? Breathe (Sheff). 2016;12(2):e38–49.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334–599.

Troosters T, Langer D, Burtin C, Chatwin M, Clini Enrico M, Emtner M, et al. A guide for respiratory physiotherapy postgraduate education: presentation of the harmonised curriculum. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(6):1900320.

Vanfleteren LE, Spruit MA, Groenen M, Gaffron S, van Empel VP, Bruijnzeel PL, et al. Clusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(7):728–35.

Houben-Wilke S, Triest FJJ, Franssen FME, Janssen DJA, Wouters EFM, Vanfleteren L. Revealing methodological challenges in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease studies assessing comorbidities: a narrative review. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2019;6(2):166–77.

Young P, Dewse M, Fergusson W, Kolbe J. Respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: predictors of nonadherence. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(4):855–9.

Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS, Spruit MA, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Physical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2006;129(3):536–44.

Spruit MA, Gosselink R, Troosters T, Kasran A, Gayan-Ramirez G, Bogaerts P, et al. Muscle force during an acute exacerbation in hospitalised patients with COPD and its relationship with CXCL8 and IGF-I. Thorax. 2003;58(9):752–6.

McDonald VM, Fingleton J, Agusti A, Hiles SA, Clark VL, Holland AE, et al. Treatable traits: a new paradigm for 21st century management of chronic airway diseases: Treatable traits down under international workshop report. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(5):1802058. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02058-2018.

Agusti A, Bel E, Thomas M, Vogelmeier C, Brusselle G, Holgate S, et al. Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(2):410–9.

Agusti A, MacNee W. The COPD control panel: towards personalised medicine in COPD. Thorax. 2013;68(7):687–90.

Peters JB, Daudey L, Heijdra YF, Molema J, Dekhuijzen PN, Vercoulen JH. Development of a battery of instruments for detailed measurement of health status in patients with COPD in routine care: the Nijmegen Clinical Screening Instrument. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):901–12.

Yadav UN, Lloyd J, Hosseinzadeh H, Baral KP, Harris MF. Do chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) self-management interventions consider health literacy and patient activation? A systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9030646.

Kruse C, Pesek B, Anderson M, Brennan K, Comfort H. Telemonitoring to manage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic literature review. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(1):e11496.

Zanaboni P, Hoaas H, Aaroen Lien L, Hjalmarsen A, Wootton R. Long-term exercise maintenance in COPD via telerehabilitation: a 2-year pilot study. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(1):74–82.

Hallensleben C, van Luenen S, Rolink E, Ossebaard HC, Chavannes NH. e Health for people with COPD in the Netherlands: a scoping review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:1681–90.

Wouters EF. Economic analysis of the confronting COPD survey: an overview of results. Respir Med. 2003;97(Suppl C):S3–14.

Spruit MA, Pitta F, Garvey C, ZuWallack RL, Roberts CM, Collins EG, et al. Differences in content and organisational aspects of pulmonary rehabilitation programmes. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(5):1326–37.

Janssen DJ, Wouters EF, Schols JM, Spruit MA. Care dependency independently predicts 2-year survival in outpatients with advanced chronic organ failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(3):194–8.

Schols AM, Ferreira IM, Franssen FM, Gosker HR, Janssens W, Muscaritoli M, et al. Nutritional assessment and therapy in COPD: a European Respiratory Society statement. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1504–20.

Spruit MA, Polkey MI, Celli B, Edwards LD, Watkins ML, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Predicting outcomes from 6-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):291–7.

Patel MS, Mohan D, Andersson YM, Baz M, Samantha Kon SC, Canavan JL, et al. Phenotypic characteristics associated with reduced short physical performance battery score in COPD. Chest. 2014;145(5):1016–24.

Spruit MA, Pennings HJ, Janssen PP, Does JD, Scroyen S, Akkermans MA, et al. Extra-pulmonary features in COPD patients entering rehabilitation after stratification for MRC dyspnea grade. Respir Med. 2007;101(12):2454–63.

Goertz YMJ, Looijmans M, Prins JB, Janssen DJA, Thong MSY, Peters JB, et al. Fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: protocol of the Dutch multicentre, longitudinal, observational FAntasTIGUE study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e021745.

Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Leue C, Gijsen C, Hameleers H, Schols JM, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in COPD patients entering pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis. 2010;7(3):147–57.

Troosters T, Probst VS, Crul T, Pitta F, Gayan-Ramirez G, Decramer M, et al. Resistance training prevents deterioration in quadriceps muscle function during acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(10):1072–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Prof. Spruit reports grants from Netherlands Lung Foundation, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, and grants from Stichting Astma Bestrijding, all outside the submitted work. Dr. Franssen reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, grants and personal fees from Novartis, and personal fees from TEVA, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. No financial support was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spruit, M.A., Van’t Hul, A., Vreeken, H.L. et al. Profiling of Patients with COPD for Adequate Referral to Exercise-Based Care: The Dutch Model. Sports Med 50, 1421–1429 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01286-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01286-9