Abstract

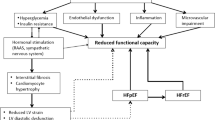

During incremental exercise tests, chronotropic incompetence (CI), which is the inability of the heart rate (HR) to rise in proportion to an increase in metabolic demand, is often observed in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Despite the fact that CI is associated with exercise intolerance and elevated risks of development of cardiovascular disease and premature death, this clinical anomaly is often ignored or overlooked by clinicians and physiologists. CI is, however, a significant clinical abnormality that deserves further attention, examination and treatment. The aetiology of CI in T2DM remains poorly understood and is complex. Certain T2DM-related co-morbidities or physiological anomalies may contribute to development of CI, such as altered blood catecholamine and/or potassium levels during exercise, structural myocardial abnormalities, ventricular and/or arterial stiffness, impaired baroreflex sensitivity and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Clinicians should thus be aware of the potential presence of yet undetected anomalies or diseases in T2DM patients who experience CI during exercise testing. However, an effective treatment for CI in T2DM is yet to be developed. Exercise training programmes seem to be the only potentially effective and feasible interventions for partial restoration of the chronotropic response in T2DM, but it remains poorly understood how these interventions lead to restoration of the chronotropic response. Studies are thus warranted to elucidate the aetiology of CI and develop an effective treatment for CI in T2DM. In particular, the impact of (different) exercise interventions on CI in T2DM deserves greater attention in future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Praet SF, van Loon LJ. Exercise therapy in type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2009;46(4):263–78.

Chen L, Magliano DJ, Zimmet PZ. The worldwide epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus—present and future perspectives. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(4):228–36.

Madden KM. Evidence for the benefit of exercise therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:233–9.

Reusch JE, Bridenstine M, Regensteiner JG. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and exercise impairment. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14(1):77–86.

Stewart KJ. Exercise training: can it improve cardiovascular health in patients with type 2 diabetes? Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(3):250–2.

Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):31–40.

Portero McLellan KC, Wyne K, Villagomez ET, et al. Therapeutic interventions to reduce the risk of progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:173–88.

Price HC, Clarke PM, Gray AM, et al. Life expectancy in individuals with type 2 diabetes: implications for annuities. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(3):409–14.

van Dijk JW, Tummers K, Stehouwer CD, et al. Exercise therapy in type 2 diabetes: is daily exercise required to optimize glycemic control? Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):948–54.

Stewart KJ. Exercise training and the cardiovascular consequences of type 2 diabetes and hypertension: plausible mechanisms for improving cardiovascular health. JAMA. 2002;288(13):1622–31.

McAuley PA, Myers JN, Abella JP, et al. Exercise capacity and body mass as predictors of mortality among male veterans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1539–43.

Nylen ES, Kokkinos P, Myers J, et al. Prognostic effect of exercise capacity on mortality in older adults with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1850–4.

Hansen D, Dendale P, Jonkers RA, et al. Continuous low- to moderate-intensity exercise training is as effective as moderate- to high-intensity exercise training at lowering blood HbA(1c) in obese type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetologia. 2009;52(9):1789–97.

Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):e147–67.

Chipkin SR, Klugh SA, Chasan-Taber L. Exercise and diabetes. Cardiol Clin. 2001;19(3):489–505.

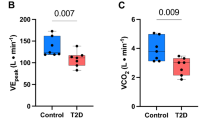

Jellis CL, Stanton T, Leano R, et al. Usefulness of at rest and exercise hemodynamics to detect subclinical myocardial disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(4):615–21.

Hansen D, Dendale P. Modifiable predictors of chronotropic incompetence in male patients with type 2 diabetes. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2014;34(3):202–7.

Brubaker PH, Kitzman DW. Chronotropic incompetence: causes, consequences, and management. Circulation. 2011;123(9):1010–20.

Corbelli R, Masterson M, Wilkoff BL. Chronotropic response to exercise in patients with atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1990;13(2):179–87.

Coyne JC, Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, et al. Prognostic importance of marital quality for survival of congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(5):526–9.

Gwinn N, Leman R, Kratz J, et al. Chronotropic incompetence: a common and progressive finding in pacemaker patients. Am Heart J. 1992;123(5):1216–9.

Lamas GA, Knight JD, Sweeney MO, et al. Impact of rate-modulated pacing on quality of life and exercise capacity—evidence from the Advanced Elements of Pacing Randomized Controlled Trial (ADEPT). Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(9):1125–32.

Dresing TJ, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ et al. Usefulness of impaired chronotropic response to exercise as a predictor of mortality, independent of the severity of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86(6):602–9.

Elhendy A, van Domburg RT, van Bax JJ, et al. The functional significance of chronotropic incompetence during dobutamine stress test. Heart. 1999;81(4):398–403.

Tanaka H, Monahan KD, Seals DR. Age-predicted maximal heart rate revisited. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(1):153–6.

Nes BM, Janszky I, Wisloff U, et al. Age-predicted maximal heart rate in healthy subjects: the HUNT Fitness Study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23(6):697–704.

Diaz A, Bourassa MG, Guertin MC, et al. Long-term prognostic value of resting heart rate in patients with suspected or proven coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(10):967–74.

Okin PM, Lauer MS, Kligfield P. Chronotropic response to exercise: improved performance of ST-segment depression criteria after adjustment for heart rate reserve. Circulation. 1996;94(12):3226–31.

Huebschmann AG, Reis EN, Emsermann C, et al. Women with type 2 diabetes perceive harder effort during exercise than nondiabetic women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2009;34(5):851–7.

Wilkoff BL, Miller RE. Exercise testing for chronotropic assessment. Cardiol Clin. 1992;10(4):705–17.

Melzer C, Witte J, Reibis R, et al. Predictors of chronotropic incompetence in the pacemaker patient population. Europace. 2006;8(1):70–5.

Brubaker PH, Kitzman DW. Prevalence and management of chronotropic incompetence in heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2007;9(3):229–35.

Sims DB, Mignatti A, Colombo PC, et al. Rate responsive pacing using cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with chronotropic incompetence and chronic heart failure. Europace. 2011;13(10):1459–63.

Lauer MS. Chronotropic incompetence: ready for prime time. J Am CollCardiol. 2004;44(2):431–2.

Keteyian SJ, Brawner CA, Schairer JR, et al. Effects of exercise training on chronotropic incompetence in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 1999;138(2 Pt 1):233–40.

Matsukawa K. Central command: control of cardiac sympathetic and vagal efferent nerve activity and the arterial baroreflex during spontaneous motor behaviour in animals. Exp Physiol. 2012;97(1):20–8.

Nobrega AC, O’Leary D, Silva BM, et al. Neural regulation of cardiovascular response to exercise: role of central command and peripheral afferents. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:478965.

Kiviniemi AM, Tulppo MP, Hautala AJ, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with chronotropic incompetence after an acute myocardial infarction. Ann Med. 2011;43(1):33–9.

De Sutter J, Van de Veire N, Elegeert I. Chronotropic incompetence: are the carotid arteries to blame? Eur Heart J. 2006;27(8):897–8.

Narkiewicz K, Pesek CA, van de Borne PJ, et al. Enhanced sympathetic and ventilatory responses to central chemoreflex activation in heart failure. Circulation. 1999;100(3):262–7.

Choi HM, Stebbins CL, Lee OT, et al. Augmentation of the exercise pressor reflex in prehypertension: roles of the muscle metaboreflex and mechanoreflex. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38(2):209–15.

Schmid A, Huonker M, Barturen JM, et al. Catecholamines, heart rate, and oxygen uptake during exercise in persons with spinal cord injury. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998;85(2):635–41.

Peinado AB, Rojo JJ, Calderon FJ, et al. Responses to increasing exercise upon reaching the anaerobic threshold, and their control by the central nervous system. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2014;6:17.

Tota B, Cerra MC, Gattuso A. Catecholamines, cardiac natriuretic peptides and chromogranin A: evolution and physiopathology of a ‘whip-brake’ system of the endocrine heart. J Exp Biol. 2010;213(Pt 18):3081–103.

Jae SY, Fernhall B, Heffernan KS, et al. Chronotropic response to exercise testing is associated with carotid atherosclerosis in healthy middle-aged men. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(8):954–9.

Fukuma N, Oikawa K, Aisu N, et al. Impaired baroreflex as a cause of chronotropic incompetence during exercise via autonomic mechanism in patients with heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97(3):503–8.

Savonen KP, Lakka TA, Laukkanen JA, et al. Usefulness of chronotropic incompetence in response to exercise as a predictor of myocardial infarction in middle-aged men without cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(7):992–8.

Phan TT, Shivu GN, Abozguia K, et al. Impaired heart rate recovery and chronotropic incompetence in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(1):29–34.

Camm AJ, Fei L. Chronotropic incompetence—part II: clinical implications. Clin Cardiol. 1996;19(6):503–8.

Meine M, Achtelik M, Hexamer M, et al. Assessment of the chronotropic response at the anaerobic threshold: an objective measure of chronotropic function. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23(10 Pt 1):1457–67.

Vandergoten P, Vijgen J, Timmermans P, et al. Chronotropic incompetence: a case report. Congest Heart Fail. 2001;7(4):202–4.

Oliveira JL, Goes TJ, Santana TA, et al. Chronotropic incompetence and a higher frequency of myocardial ischemia in exercise echocardiography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2007;5:38.

Freire CM, Moura AL, Barbosa MM, et al. Left ventricle diastolic dysfunction in diabetes: an update. Arq Bras EndocrinolMetabol. 2007;51(2):168–75.

Poanta L, Porojan M, Dumitrascu DL. Heart rate variability and diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2011;48(3):191–6.

Kitabchi AE, Wall BM. Management of diabetic ketoacidosis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(2):455–64.

Salvadori A, Fanari P, Giacomotti E, et al. Kinetics of catecholamines and potassium, and heart rate during exercise testing in obese subjects: heart rate regulation in obesity during exercise. Eur J Nutr. 2003;42(4):181–7.

Charalambous BM, Webster DJ, Mir MA. Elevated skeletal muscle sodium-potassium-ATPase in human obesity. Clin Chim Acta. 1984;141(2–3):189–95.

Mittendorfer B, Fields DA, Klein S. Excess body fat in men decreases plasma fatty acid availability and oxidation during endurance exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286(3):E354–62.

Manzella D, Paolisso G. Cardiac autonomic activity and type II diabetes mellitus. Clin Sci (Lond). 2005;108(2):93–9.

Voulgari C, Pagoni S, Vinik A, et al. Exercise improves cardiac autonomic function in obesity and diabetes. Metabolism. 2013;62(5):609–21.

Schonauer M, Thomas A, Morbach S, et al. Cardiac autonomic diabetic neuropathy. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2008;5(4):336–44.

Pop-Busui R. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: a clinical perspective. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):434–41.

Hirsh BJ, Mignatti A, Garan AR, et al. Effect of beta-blocker cessation on chronotropic incompetence and exercise tolerance in patients with advanced heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(5):560–5.

Colucci WS, Ribeiro JP, Rocco MB, et al. Impaired chronotropic response to exercise in patients with congestive heart failure: role of postsynaptic beta-adrenergic desensitization. Circulation. 1989;80(2):314–23.

Witte KK, Cleland JG, Clark AL. Chronic heart failure, chronotropic incompetence, and the effects of beta blockade. Heart. 2006;92(4):481–6.

Clark AL, Coats AJ. Chronotropic incompetence in chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 1995;49(3):225–31.

Kawasaki T, Kaimoto S, Sakatani T, et al. Chronotropic incompetence and autonomic dysfunction in patients without structural heart disease. Europace. 2010;12(4):561–6.

Gentlesk PJ, Markwood TT, Atwood JE. Chronotropic incompetence in a young adult: case report and literature review. Chest. 2004;125(1):297–301.

Munagala VK, Guduguntla V, Kasravi B, et al. Use of atropine in patients with chronotropic incompetence and poor exercise capacity during treadmill stress testing. Am Heart J. 2003;145(6):1046–50.

Ghaffari S, Sohrabi B. Effect of intravenous atropine on treadmill stress test results in patients with poor exercise capacity or chronotropic incompetence. Saudi Med J. 2006;27(2):165–9.

Brinkworth GD, Noakes M, Buckley JD, et al. Weight loss improves heart rate recovery in overweight and obese men with features of the metabolic syndrome. Am Heart J. 2006;152(4):693–6.

Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ. Effect of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on blood glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(9):2375–82.

Boden G, Sargrad K, Homko C, et al. Effect of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite, blood glucose levels, and insulin resistance in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(6):403–11.

Rock CL, Flatt SW, Pakiz B, et al. Weight loss, glycemic control, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in response to differential diet composition in a weight loss program in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1573–80.

Jenkins DJ, Wong JM, Kendall CW, et al. Effect of a 6-month vegan low-carbohydrate (‘Eco-Atkins’) diet on cardiovascular risk factors and body weight in hyperlipidaemic adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e003505.

Wong CY, Byrne NM, O’Moore-Sullivan T, et al. Effect of weight loss due to lifestyle intervention on subclinical cardiovascular dysfunction in obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m2). Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(12):1593–8.

Poirier P, Hernandez TL, Weil KM, et al. Impact of diet-induced weight loss on the cardiac autonomic nervous system in severe obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11(9):1040–7.

Brinkworth GD, Noakes M, Clifton PM, et al. Effects of a low carbohydrate weight loss diet on exercise capacity and tolerance in obese subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(10):1916–23.

Miossi R, Benatti FB, Luciade de Sa PA, et al. Using exercise training to counterbalance chronotropic incompetence and delayed heart rate recovery in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(8):1159–66.

Adams BJ, Carr JG, Ozonoff A, et al. Effect of exercise training in supervised cardiac rehabilitation programs on prognostic variables from the exercise tolerance test. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(10):1403–7.

Morton RD, West DJ, Stephens JW, et al. Heart rate prescribed walking training improves cardiorespiratory fitness but not glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(1):93–9.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Inez Wens (Rehabilitation Research Center [REVAL], BIOMED, Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences, Hasselt University, Diepenbeek, Belgium) for support and time-saving advice regarding certain aspects of this article. No conflicts of interest are reported. No sources of funding were used in the preparation of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keytsman, C., Dendale, P. & Hansen, D. Chronotropic Incompetence During Exercise in Type 2 Diabetes: Aetiology, Assessment Methodology, Prognostic Impact and Therapy. Sports Med 45, 985–995 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0328-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0328-5