Abstract

Background and Objective

Recent evidence has shown that online surveys can reliably collect preference data, which markedly decrease the cost of health preference studies and expand their representativeness. As the use of mobile technology continues to grow, we wanted to examine its potential impact on health preferences.

Methods

Two recently completed discrete choice experiments using members of the US general population (n = 15,292) included information on respondent device (cell phone, tablet, Mac, PC) and internet connection (business, cellular, college, government, residential). In this analysis, we tested for differences in respondent characteristics, participation, response quality, and utility values for the 5-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) by device and connection.

Results

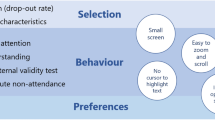

Compared to Mac and PC users, respondents using a cell phone or tablet had longer completion times and were significantly more likely to drop out during the surveys (p < 0.001). Tablet users also demonstrated more logical inconsistencies (p = 0.05). Likewise, respondents using a cellular internet connection exhibit significantly less consistency in their health preferences. However, matched samples for tablets and cell phones produced similar EQ-5D-5L utility values (mean differences < 0.06 on a quality-adjusted life-year [QALY] scale for all potential health states).

Conclusion

Allowing respondents to complete online surveys using a cell phone or tablet or over a cellular connection substantially increases the diversity of respondents and the likelihood of obtaining a representative sample, as many individuals have cell phones but not a computer. While the results showed systematic variability in participation and response quality by device and connection type, this study did not show any meaningful changes in utility values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability Statement

The data and statistical code are available from the corresponding author on request.

Notes

Separate models were run for mobile device users and tablets.

The design of the TDL Survey contained a limited number of health states, preventing a full valuation.

A quantile regression model was chosen due to the significant number of outliers in the data (i.e., individuals who took a break in the middle of the survey).

Each of the studies uses quota sampling from a nationally representative panel, and it has often taken significantly longer to obtain the required number of responses from these demographic groups.

References

Bansback N, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Anis A. Using a discrete choice experiment to estimate health state utility values. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):306–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.11.004.

Craig BM, Greiner W, Brown DS, Reeve BB. Valuation of child health-related quality of life in the United States. Health Econ. 2016;25(6):768–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3184.

Norman R, Viney R, Brazier J, Burgess L, Cronin P, King M, et al. Valuing SF-6D health states using a discrete choice experiment. Med Decis Mak. 2014;34(6):773–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x13503499.

Viney R, Norman R, Brazier J, Cronin P, King MT, Ratcliffe J, et al. An Australian discrete choice experiment to value EQ-5D health states. Health Econ. 2014;23(6):729–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2953.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200826080-00004.

Stolk EA, Oppe M, Scalone L, Krabbe PFM. Discrete choice modeling for the quantification of health states: the case of the EQ-5D. Value Health. 2010;13(8):1005–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00783.x.

Scalone L, Stalmeier PFM, Milani S, Krabbe PFM. Values for health states with different life durations. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(9):917–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0634-0.

Muhlbacher AC, Rudolph I, Lincke HJ, Nubling M. Preferences for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-149.

Krabbe PFM, Devlin NJ, Stolk EA, Shah KK, Oppe M, van Hout B, et al. Multinational evidence of the applicability and robustness of discrete choice modeling for deriving EQ-5D-5L health-state values. Med Care. 2014;52(11):935–43.

Soekhai V, de Bekker-Grob EW, Ellis AR, Vass CM. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(2):201–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0734-2.

Couper MP, Tourangeau R, Conrad FG, Crawford SD. What they see is what we get—response options for web surveys. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2004;22(1):111–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439303256555.

Revilla M, Toninelli D, Ochoa C, Loewe G. Do online access panels need to adapt surveys for mobile devices? Internet Res. 2016;26(5):1209–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-02-2015-0032.

Brosnan K, Grun B, Dolnicar S. PC, phone or tablet? Use, preference and completion rates for web surveys. Int J Market Res. 2017;59(1):35–55. https://doi.org/10.2501/ijmr-2016-049.

Mavletova A. Data quality in PC and mobile web surveys. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2013;31(6):725–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313485201.

de Bruijne M, Wijnant A. Mobile response in web panels. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2014;32(6):728–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314525918.

Liebe U, Glenk K, Oehlmann M, Meyerhoff J. Does the use of mobile devices (tablets and smartphones) affect survey quality and choice behaviour in web surveys? J Choice Model. 2015;14:17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocm.2015.02.002.

Lambert AD, Miller AL. Living with smartphones: does completion device affect survey responses? Res High Educ. 2015;56(2):166–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9354-7.

Couper MP, Peterson GJ. Why do web surveys take longer on smartphones? Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2017;35(3):357–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439316629932.

Lynn P, Kaminska O. The impact of mobile phones on survey measurement error. Public Opin Q. 2013;77(2):586–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs046.

Lugtig P, Toepoel V. The use of PCs, smartphones, and tablets in a probability-based panel survey: effects on survey measurement error. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2016;34(1):78–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315574248.

Toepoel V, Lugtig P. What happens if you offer a mobile option to your web panel? Evidence from a probability-based panel of internet users. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2014;32(4):544–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313510482.

Schlosser S, Mays A. Mobile and dirty: does using mobile devices affect the data quality and the response process of online surveys? Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2018;36(2):212–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317698437.

de Bruijne M, Wijnant A. Comparing survey results obtained via mobile devices and computers: an experiment with a mobile web survey on a heterogeneous group of mobile devices versus a computer-assisted web survey. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2013;31(4):482–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313483976.

Tourangeau R, Sun HY, Yan T, Maitland A, Rivero G, Williams D. Web surveys by smartphones and tablets: effects on data quality. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2018;36(5):542–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317719438.

Toninelli D, Revilla M. Smartphones vs PCs: does the device affect the web survey experience and the measurement error for sensitive topics? A replication of the Mavletova & Couper’s 2013 experiment. Surv Res Methods. 2016;10(2):153–69. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2016.v10i2.6274.

Mavletova A, Couper MP. Sensitive topics in PC web and mobile web surveys: is there a difference? Surv Res Methods. 2013;7(3):191–205.

Keusch F, Yan T. Web versus mobile web: an experimental study of device effects and self-selection effects. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2017;35(6):751–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439316675566.

Craig BM, Rand K, Bailey H, Stalmeier PF. Quality-adjusted life-years without constant proportionality. Value Health. 2018;29(9):1124–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.02.004.

Jakubczyk M, Craig BM, Barra M, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, Hartman JD, Huynh E, et al. Choice defines value: a predictive modeling competition in health preference research. Value Health. 2018;21(2):229–38.

Euroqol. About the EQ-5D-5L. 2018. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/. Accessed 22 Mar 2018.

Survey K. Mobile surveys. https://www.keysurvey.com/survey-software/mobile-surveys/2017. Accessed 9 May 2017.

Craig BM, Runge SK, Rand-Hendriksen K, Ramos-Goni JM, Oppe M. Learning and satisficing: an analysis of sequence effects in health valuation. Value Health. 2015;18(2):217–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.11.005.

Campbell D, Morkbak MR, Olsen SB. Response time in online stated choice experiments: the non-triviality of identifying fast and slow respondents. J Environ Econ Policy. 2017;6(1):17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/21606544.2016.1167632.

Sendelbah A, Vehovar V, Slavec A, Petrovic A. Investigating respondent multitasking in web surveys using paradata. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55:777–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.028.

Stern MJ. The use of client-side paradata in analyzing the effects of visual layout on changing responses in web surveys. Field Methods. 2008;20(4):377–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x08320421.

Rossmann J, Gummer T. Using paradata to predict and correct for panel attrition. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2016;34(3):312–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315587258.

Olson K. Paradata for nonresponse adjustment. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2013;645(1):142–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212459475.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55.

Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Statistical Software Components. 2015. https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s432001.htm. Accessed 30 May 2017.

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv. 2008;22(1):31–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00527.x.

Bradley RA, Terry ME. Rank analysis of incomplete block designs: I. The method of paired comparisons. Biometrika. 1952;39(3/4):324–45.

Zermelo E. Die berechnung der turnier-ergebnisse als ein maximumproblem der wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung. Math Z. 1929;29(1):436–60.

Craig BM, Rand K. Choice defines QALYs. Med Care. 2018;56(6):529–36.

Jonker MF, Donkers B, de Bekker-Grob EW, Stolk EA. Advocating a paradigm shift in health-state valuations: the estimation of time-preference corrected QALY tariffs. Value Health. 2018;21(8):993–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.01.016.

DeShazo JR, Fermo G. Designing choice sets for stated preference methods: the effects of complexity on choice consistency. J Environ Econ Manag. 2002;44(1):123–43. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeem.2001.1199.

Swait J, Louviere J. The role of the scale parameter in the estimation and comparison of multinomial logit-models. J Mark Res. 1993;30(3):305–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172883.

Hensher D, Louviere J, Swait J. Combining sources of preference data. J Econ. 1998;89(1):197–221.

Louviere JJ, Islam T, Wasi N, Street D, Burgess L. Designing discrete choice experiments: do optimal designs come at a price? J Consum Res. 2008;35(2):360–75. https://doi.org/10.1086/586913.

Devlin NJ, Hansen P, Kind P, Williams A. Logical inconsistencies in survey respondents’ health state valuations—a methodological challenge for estimating social tariffs. Health Econ. 2003;12(7):529–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.741.

Dolan P, Kind P. Inconsistency and health state valuations. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(4):609–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00161-1.

Al Sayah F, Johnson JA, Ohinmaa A, Xie F, Bansback N, on behalf of the Canadian EQ-5D Valuation Study Group. Health literacy and logical inconsistencies in valuations of hypothetical health states: results from the Canadian EQ-5D-5L valuation study. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(6):1483–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1495-z.

Badia X, Roset M, Herdman M. Inconsistent responses in three preference-elicitation methods for health states. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(7):943–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00182-3.

Yang ZH, van Busschbach J, Timman R, Janssen MF, Luo N. Logical inconsistencies in time trade-off valuation of EQ-5D-5L health states: whose fault is it? PLoS One. 2017;12(9):10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184883.

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Econometric models based on count data. Comparisons and applications of some estimators and tests. J Appl Econ. 1986;1(1):29–53.

Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2010.

Greene WH. Econometric analysis. 5th ed. Chennai: Pearson Education India; 2003.

Craig BM, Pickard AS, Rand-Hendriksen K. Do health preferences contradict ordering of EQ-5D labels? Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1759–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0897-z.

Jonker MF, Donkers B, de Bekker-Grob EW, Stolk EA. Effect of level overlap and color coding on attribute non-attendance in discrete choice experiments. Value Health. 2018;21(7):767–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.10.002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH and BC shared much of the responsibility in creating the manuscript. JH performed the literature review and wrote the Introduction, Methods, and Discussion sections. BC wrote the Results section. The authors contributed equally in the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Funding support for this research was provided by a grant from the EuroQol Research Foundation (2016690). The views presented in the study do not necessarily reflect those of the EuroQol Group, and the publication of study results was not contingent on the sponsor’s approval or censorship of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

John Hartman and Benjamin Craig declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in either study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hartman, J.D., Craig, B.M. Does Device or Connection Type Affect Health Preferences in Online Surveys?. Patient 12, 639–650 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00380-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00380-z