Abstract

Background

Agomelatine is a melatonin receptor agonist and serotonin 5-HT2C receptor antagonist indicated for depression in adults. Hepatotoxic reactions like acute liver injury (ALI) are an identified risk in the European risk management plan for agomelatine. Hepatotoxic reactions have been reported for other antidepressants, but population studies quantifying these risks are scarce. Antidepressants are widely prescribed, and users often have risk factors for ALI (e.g. metabolic syndrome).

Objective

The goal was to estimate the risk of ALI associated with agomelatine and other antidepressants (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, and amitriptyline) when compared with citalopram in routine clinical practice.

Method

A nested case–control study was conducted using data sources in Denmark, Germany, Spain, and Sweden (study period 2009–2014). Three ALI endpoints were defined using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes: primary (specific codes) and secondary (all codes) endpoints used only hospital discharge codes; the tertiary endpoint included both inpatient and outpatient settings (all codes). Validation of endpoints was implemented. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for current use were estimated for each data source and combined.

Results

We evaluated 3,238,495 new antidepressant and 74,440 agomelatine users. For the primary endpoint, the OR for agomelatine versus citalopram was 0.48 (CI 0.13–1.71). Results were also < 1 when no exclusion criteria were applied (OR 0.37; CI 0.19–0.74), when all exclusion criteria except alcohol and drug abuse were applied (OR 0.47; CI 0.20–1.07), and for the secondary (OR 0.40; CI 0.05–3.11) and tertiary (OR 0.79; CI 0.50–1.25) endpoints. Regarding other antidepressants versus citalopram, most OR point estimates were also below one, although with varying widths of the 95% CIs. The result of the tertiary endpoint and the sensitivity analyses of the primary endpoint were the most precise.

Conclusion

In this study, using citalopram as a comparator, agomelatine was not associated with an increased risk of ALI hospitalisation. The results for agomelatine should be interpreted in the context of the European risk minimisation measures in place. Those measures may have induced selective prescribing and could explain the lower risk of ALI for agomelatine when compared with citalopram. Most other antidepressants evaluated had ORs suggesting a lower risk than citalopram, but additional studies are required to confirm or refute these results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Agomelatine did not increase the risk of hospitalisation due to acute liver injury (ALI) in the studied populations when compared to citalopram. Results were robust in multiple sensitivity analyses. |

In the populations studied, risk minimisation measures were in place and may have contributed to the lower risk found for agomelatine when compared with citalopram. Thus, compliance with relevant contra-indications, precautions of use, and biological liver testing before and during treatment are still required to prescribe agomelatine. |

Of the other antidepressants, sertraline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, and amitriptyline had a lower risk of ALI hospitalisation when compared to citalopram. |

1 Background

Agomelatine (Valdoxan, Thymanax) is a melatonin receptor agonist and serotonin 5-HT2C antagonist indicated for major depressive episodes in adults [1]. Hepatotoxic reactions are an identified risk of agomelatine included in the European risk management plan and the drug label, which recommend that aminotransferase levels are checked before treatment initiation and then after 3, 6, 12, and 24 weeks and following a dose increase [2]. While other antidepressant drugs used in Europe do not have similar recommendations, hepatotoxic reactions do occur with some of them. The severity and frequency of those reactions vary among antidepressants. According to studies based only on case reports, they seem to be more common and severe with use of tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors than with use of serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (0.5–1%) [3, 4]. Acute liver injury (ALI) refers to the sudden appearance of liver test abnormalities and encompasses a spectrum of clinical diseases ranging from mild biochemical abnormalities to acute liver failure [5]. When known causes of ALI have been ruled out and criteria for causality of a specific drug are met, the term drug-induced liver injury is used instead [5, 6]. Standardised definitions of ALI for use in epidemiological studies have been proposed [5, 7], and the incidence of ALI related to antidepressant use requiring hospitalisation has been estimated to be one to four cases per 100,000 patient-years [3].

Antidepressant drugs are currently among the most widely used drugs in Western countries [8, 9], and often patients using them have risk factors for ALI, such as alcohol and drug abuse and dependence, and metabolic syndrome [10,11,12]. Other risk factors for ALI include older age, female sex, concurrent use of hepatotoxic medications, previous acute and chronic hepatic, biliary, and pancreatic conditions, malnutrition, HIV infection, and chronic inflammatory diseases [13, 14].

Two previous studies on the risk of ALI associated with the use of duloxetine have been conducted using Ingenix Research Data Mart and the Optum Research Database in the United States [15, 16], suggesting an increased risk of ALI with duloxetine when compared with venlafaxine [15, 16] and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [15].

The primary goal of this post-authorisation safety study [17], using a nested case–control analysis, was to evaluate the risk of hospitalisation for ALI associated with agomelatine and eight other antidepressant drugs as used in current medical practice compared with citalopram.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Study Period

In brief, we conducted a large, multinational, retrospective longitudinal cohort and nested case–control study comparing new users of agomelatine (main exposure of interest) and new users of eight other study antidepressants with new users of citalopram (common reference group). Citalopram was selected as a comparator because it was the most commonly used antidepressant in three of the four countries and, according to literature reviews available at the time of writing the protocol, was among the antidepressants with the least potential for hepatotoxicity [3, 4]. The other antidepressants were selected because they were commonly used across all countries. The study period in each data source started after the launch of agomelatine in the respective country (in 2009 or 2010) and ended with the last year for which data were available in each data source (2013 or 2014). The full study protocol can be accessed at the European Union Electronic Register of Post-Authorisation Studies (EU PAS Register # EUPAS10446) [18].

2.2 Setting

This study was conducted in automated health databases in four countries: Spain (SIDIAP [Information System for Research in Primary Care] [19] and EpiChron Cohort [EpiChron Research Group on Chronic Diseases] [20]), Germany (GePaRD [German Pharmacoepidemiological Research Database]) [21,22,23] and Denmark [24,25,26,27,28,29] and Sweden [29,30,31] (using their national registers). Characteristics of the databases are described in Online Resource 1 (see the electronic supplementary material).

2.3 Study Population

The study cohort included all individuals aged 18 years or older at the date of the first-recorded prescription fill of any of the study antidepressants during the study period(s) who (1) had not received a prescription fill for the same study antidepressant within the prior 12 months (new users) and (2) had at least 12 months of continuous enrolment in the data source before the first prescription fill defining cohort entry. Thus, one patient could contribute to several antidepressant cohorts if eligibility criteria were fulfilled. For women, an additional eligibility criterion was absence of pregnancy at the start date of antidepressant use. Patients with a history of liver disease or risk factors for liver disease (e.g. alcohol and drug abuse and dependence-related disorders), chronic biliary or pancreatic disease, malignancy, or other life-threatening conditions (e.g. cancer, HIV infection) were excluded from the study cohort (see Online Resource 2 in the electronic supplementary material for a detailed list of exclusion criteria).

2.4 Endpoints Ascertainment: Selection of Cases and Controls

The primary endpoint was ascertained in all data sources and defined as any patient with a specific hospital discharge diagnosis code of ALI from either the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10).

The secondary endpoint was defined as validated cases of ALI (see below) identified with specific and nonspecificFootnote 1 hospital discharge diagnosis codes and was evaluated only in Spain (EpiChron and SIDIAP) and Denmark.

The exploratory tertiary endpoint was assessed based on specific and nonspecific codes identified in both hospital and outpatient settings and was evaluated in all data sources regardless of whether validation was feasible. A sensitivity analysis restricted to validated cases was conducted in the three data sources in which validation was implemented. The list of specific and nonspecific codes is included in the electronic supplementary material (Online Resource 3). The list of codes was adapted to the country-specific ICD classification system used. The investigators in each country reviewed the codes list and made small adaptations when necessary. Additionally, local clinicians were consulted.

Potential cases of ALI identified with specific and nonspecific codes were confirmed by validation processes according to the definition criteria established by an international expert working group [5]. The definition criteria are based on increases in the levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and bilirubin over the upper limit of normality (ULN) with less than 1 year of persistence: (≥ 5 × ULN ALT) or (≥ 2 × ULN ALP) or (≥ 3 × ULN ALT and > 2 × ULN bilirubin). This study was not designed to evaluate causality at the individual level to ascertain whether a specific case with phenotypical ALI had drug-induced liver injury or not. Rather, the study was designed to examine the potential causal role of agomelatine and other antidepressants when compared with citalopram in the development of ALI at the population level. Thus, no formal evaluations using the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) [32] were implemented at the individual case level. Potential cases were adjudicated by trained clinicians based on review of information abstracted from medical records. This information included timing and results of liver enzymes and information on presence or absence of excluding conditions [33]. Thus, the clinical reviewers were adjudicating whether the individual potential cases met the study definition criteria of ALI and whether excluding conditions were present, not whether they met criteria for causality between antidepressant use and liver injury. Validity of the electronic algorithms based on diagnosis codes used in the secondary and tertiary endpoints was assessed by calculating the positive predictive value (PPV), defined as the probability that a patient classified as a potential case was a confirmed case of ALI based on the reviewed data (excluding nonevaluable cases from the denominator).

In Germany, a companion external validation study (ALIVAL) of the ICD discharge and outpatient diagnosis codes for ALI was conducted in a German hospital to estimate the PPV of algorithms used in the GePaRD data source to identify potential cases of the primary and tertiary endpoints. In Sweden, no validation of cases was implemented.

In the case–control analysis, all ALI cases identified according to the definition of each endpoint in the study cohort were included as cases. Controls were selected from the study cohort using density sampling. Up to 20 controls per case were randomly selected from the risk set of each case. Controls were matched to cases on age and sex, index date, and calendar year of study (cohort) entry.

2.5 Exposure Variables and Confounding Factors

Time at risk was defined according to the days of supply of each prescription fill plus a period of 40 days. Days of supply were the assumed number of days of treatment associated with each prescription fill. The period of 40 days was added to account for stockpiling and less than perfect adherence [34].

In the nested case–control main analysis, use status was classified for each patient and each antidepressant into four mutually exclusive categories according to time at risk of the most recent prescription fill received on or before the index date:

-

Current use: when the time at risk of the most recent prescription fill overlapped the index date

-

Recent use: when the time at risk ended within 60 days before the index date

-

Past use: when the time at risk ended more than 60 days before the index date

-

Nonuse: when there was no prescription fill of the study drug under consideration before the index date

Confounding factors were those related to the risk of ALI [13, 14, 35] and to exposure to agomelatine or another study antidepressant. Age, sex, and year of entrance in the cohort (through matching); acute alcohol intoxication; obesity; other components of metabolic syndrome (hypertension and dyslipidaemia); diabetes; inflammatory bowel disease; pre-existing comorbidity measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index; acute biliary and pancreatic disease; peptic ulcer disease; rheumatic diseases; concurrent use of hepatotoxic drugs (list of drugs available in Online Resource 4; see the electronic supplementary material); concurrent use of other antidepressants (different from study antidepressants); number of liver tests performed; and health care resource utilization measures were considered potential risk factors or confounders.

2.6 Statistical Analyses

Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for ALI for current use of each study antidepressant were estimated using conditional logistic regression models, with current use of citalopram as the reference category (main analysis).

Crude ORs (and 95% CIs) were estimated including only the exposure variables in the conditional logistic regression model. Due to the matching of cases and controls and conditional analyses, these crude ORs were adjusted by age, sex, and calendar year at study entry, but were referred to as crude ORs regarding the rest of the confounders. Because of the low number of cases in some data sources, the original exposure variables had to be reclassified into fewer categories (i.e. current use vs. other), and in each of the separate logistical models comparing citalopram with each one of the other antidepressants, a new single exposure variable was created to classify current use status of the two antidepressants being compared.

Important risk factors and potential confounders were a priori included in the models. Other potential confounders were tested in a backward elimination process [36] to avoid problems with zero cells in the analysis. In the nested case–control analysis, presence of risk factors and confounders was evaluated at any time before the index date, but some variables (e.g. concurrent use of hepatotoxic drugs) were evaluated just 6 months before the index date. In Online Resource 5, we include a table providing additional details on the timing of evaluation for the different potential confounders.

For each of the three study endpoints, meta-analysis was used to combine the adjusted OR estimates obtained from the nested case–control analysis in the different data sources. Combined ORs and 95% CIs for ALI were produced first using random-effects models [37]. To assess heterogeneity in the meta-analysis, the I2 statistic was employed. When results were homogeneous across databases, fixed-effects models were used, and these results were presented in the results tables. When the I2 test statistic was 30% or higher for any of the antidepressants, random-effects models were presented for all antidepressants. Forest plots were created for each analysis table to display the adjusted combined and data source–specific results. When no events were observed in some of the data sources, we included only the results from data sources with observed events.

To check the robustness of the results, several planned sensitivity analyses were performed: the effect of adding 15 days or 60 days (instead of 40 days) to the days of supply of the most recent prescription before the index date was explored; the effect of recent and past use of each study antidepressant was compared with current use of citalopram; switching and multiple current use were compared with current single use of citalopram; and analyses restricted to cases without known causes of ALI were conducted. The implementation of those sensitivity analyses was limited in most data sources by the limited number of cases. In addition, two post hoc sensitivity analyses recommended by regulatory reviewers were implemented for the primary endpoint. In one, no exclusion criteria were implemented, and in the other, all study exclusion criteria were applied except those related to alcohol use disorder and drug abuse.

3 Results

A total of 3,238,495 new users of antidepressants (EpiChron, n = 185,628; SIDIAP, n = 203,101; the GePaRD, n = 817,072; the Danish National Health Registers, n = 664,205; and the Swedish National Registers in Sweden, n = 1,368,489) were included in the main analysis, of which 74,440 were new users of agomelatine (Table 1). Agomelatine, the most recently launched of the studied antidepressants, was the least dispensed antidepressant in the study. A table presenting the distribution of the main confounder factors at cohort entry in each data source is included in Online Resource 6 (see the electronic supplementary material).

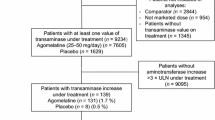

In the main analysis, a total of 472 cases were identified for the ALI primary endpoint (specific hospital discharge codes), ranging from 19 (SIDIAP) to 170 (Danish National Health Registers). Online Resource 7 presents the number of cases and controls in each data source and the association between potential confounders and the ALI primary endpoint in the multivariable adjusted models, which was different in the five data sources. Table 2 displays the number of new users in each antidepressant cohort and the number of cases and controls by endpoint, antidepressant cohort, and overall numbers.

3.1 Primary Endpoint

Online Resource 8 presents the age- and sex-standardised incidence rates of ALI for the primary endpoint by data source and studied antidepressant. The estimates were imprecise, ranged from 0 to 27 cases per 100,000 person-years, and were overall within the range of the ALI incidence rates described previously in the literature [38]. The PPVs for the specific codes used to identify the primary endpoint ranged from 60.0% (SIDIAP) to 84.2% (EpiChron) in the study data sources, and the PPV was 62.7% in the external validation study in Germany (ALIVAL).

Results of the case–control analyses for the current use of agomelatine compared with current use of citalopram are presented in Table 3.

Current use of agomelatine compared with current use of citalopram yielded ORs below 1.00 in all data sources with cases (no cases under current use of agomelatine were identified in SIDIAP and Sweden) with imprecise estimates. The combined (meta-analysis) adjusted OR for current use of agomelatine compared with citalopram was 0.48 (95% CI 0.13–1.71).

In the post hoc sensitivity analysis without exclusions (including 4,833,774 new users of antidepressants, of which 117,240 were new users of agomelatine), more cases were identified, and therefore, the OR estimates were more precise and in line with the main analysis. The combined adjusted OR for current use of agomelatine compared with citalopram was 0.37 (95% CI 0.19–0.74). The point estimates were homogeneous across all data sources for the sensitivity analysis without exclusions.

In the post hoc sensitivity analysis including patients with disorders related to alcohol and drug abuse (3,531,529 new users of antidepressants, of which 84,210 were new users of agomelatine), the combined adjusted OR for current use of agomelatine compared with citalopram was 0.47 (95% CI 0.20–1.07). The individual point estimates from the different data sources were less homogeneous: both EpiChron and SIDIAP, which had the smallest agomelatine cohorts, showed OR estimates above 1.00 with wide 95% CIs.

Figure 1 presents the combined results for current use of each antidepressant in the main analysis and the two post hoc sensitivity analyses for the primary endpoint. For all antidepressants except fluoxetine and paroxetine, the combined point estimates were less than 1.00 in the main analysis. The 95% CIs were more imprecise in the main analysis than in the two post hoc sensitivity analyses, in which all antidepressants had ORs below 1.00 when compared with citalopram.

Current use combined adjusted estimates for all antidepressants (primary endpoint main and two sensitivity post hoc analyses removing exclusion conditions). Odds ratio estimates were adjusted for confounding factors. The list of confounders differed by data source and type of analysis (main vs. sensitive analyses). The following confounders were included in most analyses: obesity, hyperlipidaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia, diabetes, hypertension, indication of treatment with antidepressants for major depression, indication of treatment with antidepressants for anxiety disorders, indication of treatment with antidepressants for other mental and behavioural disorders, Charlson Comorbidity Index, number of liver tests performed, concurrent use of hepatotoxic drugs, and concurrent use of other antidepressants. CI confidence interval, GePaRD German Pharmacoepidemiological Research Database, SIDIAP Information System for Research in Primary Care

Results of the planned sensitivity analyses (including the ones assessing different exposure definitions and analysis excluding known causes of ALI) for agomelatine and the other antidepressants were, in general, consistent with the main analysis and produced combined OR point estimates for agomelatine below 1.00 for current use (data not shown). Results for all antidepressants, combined and in each individual data source, and for the three endpoints are available in the electronic supplementary material (Online Resources 9–11).

3.2 Secondary Endpoint

The secondary endpoint included only cases that had been confirmed after validation, which resulted in a lower number of events than for the primary endpoint. A total of 178 confirmed cases (150 in Denmark, 20 in EpiChron, eight in SIDIAP) and 3540 controls were identified. Confirmed cases during current use of agomelatine were identified in Denmark only; the adjusted OR estimate for current use was 0.40 (95% CI 0.05–3.11). For the other antidepressants when compared with citalopram, most combined OR point estimates were less than one, except that of fluoxetine. The estimates were imprecise (Online Resource 10).

3.3 Tertiary Endpoint

Overall, there were 17,118 cases of the tertiary study endpoint and 342,070 controls. The GePaRD had overall the largest number of cases (11,917), followed by SIDIAP (2826), Sweden (1099), Denmark (1088), and EpiChron (268). The PPV of the tertiary endpoint cases was low in all data sources, but especially in SIDIAP (7.7%). The highest PPVs (47.0%) were found in Denmark and the ALIVAL external study (Germany, 45.1%). In EpiChron, the PPV was 25.4%. In Sweden, no validation of cases was implemented.

For this tertiary endpoint, the combined estimate for agomelatine for current use was 0.79 (95% CI 0.50–1.25). The results were heterogeneous (I2 = 71%, indicating the presence of strong heterogeneity). The individual data source–adjusted ORs for current use of agomelatine were also below 1.00, except in the GePaRD, and ranged from 0.36 (95% CI 0.11–1.25) in Sweden to 0.95 (95% CI 0.33–2.75) in EpiChron. In the GePaRD, the adjusted OR was 1.24 (95% CI 1.07–1.42) and contrasted with the ORs observed in Denmark and Sweden, which were approximately 0.5 (Online Resource 12). In Denmark, the adjusted OR estimate for current use of agomelatine was 0.44 (95% CI 0.22–0.87). In the sensitivity analysis that included only confirmed cases (confirmed cases available only in Denmark; see Online Resources 13) of the tertiary endpoint, the OR was 0.75 (95% CI 0.17–3.22).

For the other antidepressants (Online Resource 11), all combined OR estimates were between 0.94 and 1.11. There was an indication of heterogeneity for mirtazapine, duloxetine, and amitriptyline (I2 > 50%, indicating at least moderate heterogeneity). The combined OR 95% CIs of the tertiary endpoint were more precise than for the other two endpoints. In the sensitivity analysis that included only confirmed cases (Online Resource 13), all combined OR estimates were below one except for duloxetine (OR 1.03; 95% CI 0.60–1.79).

4 Discussion

Use of agomelatine was not associated with higher risk of ALI hospitalisation compared with use of citalopram in a large cohort comprising 3.2 million new users of antidepressants in five populations from four countries: Spain, Denmark, Sweden, and Germany. Although precision of the combined risk estimates was low for the primary endpoint, the results were similar and more precise in the unrestricted sensitivity analyses and consistent both with the other sensitivity analyses and with the results of the other two endpoints considered. In the combined analysis, no increase in risk was observed in populations including alcoholic patients or patients with other various risk factors. For the other antidepressants, most presented ORs below 1, except for fluoxetine and paroxetine. Further, as for agomelatine, similar results were obtained when using other outcome definitions, that is, the secondary and tertiary endpoints.

The estimates of risk associated with agomelatine use in this study are consistent with those from a recent cohort study funded by the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety and conducted using the French health insurance database. This study did not find an increased risk of severe liver injury associated with the use of agomelatine compared with use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (adjusted hazard ratio 1.07; 95% CI 0.51–2.23) [39].

In our study, analyses of most study antidepressants yielded ORs of ALI hospitalisation lower than 1.00 when compared with citalopram in the combined analyses for all endpoints. Since we had no pre-suspicion that citalopram would carry a particularly high risk of ALI, the consistency in the direction of this association across antidepressants was unexpected. However, the limitations discussed hereafter, particularly those related to the low number of cases, preclude drawing definite conclusions. Citalopram is, in many countries, one of the first-line treatment options and is considered one of the safest antidepressants and could be selectively prescribed to those cases at the highest risk of ALI, which could potentially result in confounding by indication, but other antidepressants in this study share a similar drug prescription pattern. Although citalopram has been considered safe when compared with other antidepressants in analyses of spontaneous reports of adverse drug reactions [40, 41] and in reviews of published clinical data [3], two epidemiological studies found an increased risk of drug-induced liver injury associated with citalopram use [42, 43]. Of note, the French study [39] did not find any relevant differences in risk between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, and other antidepressants (e.g. agomelatine).

As in any study in automated data, misclassification of exposure status, occurrence of incident events, and the covariates to be included in the multivariable models is possible. In this study, this would likely have resulted in nondifferential misclassification of the endpoints, potentially biasing the estimates towards unity. However, small differences in misclassification of the exposure or the disease may result in bias towards or away from unity in an unpredictable manner [44].

To minimise misclassification of endpoints, specific codes were used for the primary endpoint, and validation of the secondary endpoint that included nonspecific codes was implemented. Validation of potential cases was implemented in a sensitivity analysis of the tertiary endpoint. The sources and the quantity of information available differed across data sources and the underlying health care systems (e.g. body mass index was available in data sources with access to primary care data), which may explain some of the differences observed in the prevalence of some clinical features, as well as the differences observed across the study data sources in the PPVs and some OR estimates. For the primary endpoint, the PPVs of the specific codes ranged from 60% in SIDIAP to 84% in EpiChron and were consistent or higher than the estimates from previous studies [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. In SIDIAP, access to hospital medical records was not available, and PPVs would have probably been higher otherwise. Some PPV estimates were imprecise, especially in SIDIAP and in the ALIVAL study, and differences between data sources could be also explained by random error. Importantly, however, the results of the secondary endpoint that included only confirmed cases were consistent with the results of the primary endpoint.

As already mentioned, the number of identified events of the primary and secondary endpoint was limited among agomelatine users and users of other antidepressants. For the tertiary endpoint, the number of cases was much higher (especially in the GePaRD and SIDIAP), yet the low PPVs observed for this endpoint definition limit the interpretation of these results in the analysis that included unconfirmed cases.

Patients taking agomelatine undergo routine liver enzyme monitoring as a risk minimisation measure. Therefore, patients at known risk of developing ALI may not have been prescribed agents (such as agomelatine) that are thought to be associated with an increased risk of ALI. Moreover, detection of liver enzyme elevations may be more likely in this group and prevent patients from starting treatment with agomelatine, or if agomelatine treatment has been started, treatment may be stopped earlier or cases of liver injury may be detected more frequently and earlier than if liver enzyme monitoring had not been conducted. In the context of observational studies using data from routine clinical practice, these scenarios could lead to selective prescribing, surveillance bias, or both. Selective prescribing, i.e. the less frequent prescription of agomelatine to patients with known risk factors for ALI or with evidence of existing liver damage measured by liver function tests, would shift the results in favour of agomelatine and lead to an apparently lower risk of ALI among agomelatine new users when compared with new users of citalopram. The comparison of the different antidepressant cohorts in the main analysis and in the sensitivity analysis including patients with known risk factors (data not shown) do not seem to indicate that agomelatine is less prescribed among patients with known risk factors (e.g. chronic liver conditions). Moreover, the results of the sensitivity analysis are consistent with the results of the main analysis, the latter excluding patients at risk of ALI, and show an OR estimate also below one and with larger precision. However, because of the risk minimisation measures in place, selective prescribing could still take place (e.g. agomelatine would not be prescribed to those patients with abnormal liver tests or those with contraindications and precautions of use according to approved label), and this cannot be assessed with the data available. Thus, it is plausible that selective prescribing may have influenced the results of the study, which need to be interpreted in the context of the risk minimisation measures in place for agomelatine. In fact, our results suggest that the risk minimization measures in place for agomelatine are effective.

Similarly, surveillance bias is unlikely to have had a large impact on the reported estimates for the primary and secondary endpoints, as these included only hospitalised and thereby more severe cases. In the combined results, no risk increase was found for the tertiary endpoint, which was in principle more sensitive to surveillance bias and misclassification than the primary and secondary endpoints. Surveillance bias would have resulted in ORs above 1.00. However, in the context of low PPVs, nondifferential misclassification would produce bias towards seeing no association.

The possibility of residual confounding cannot be discarded. As mentioned, the amount of information on some potential confounders (e.g. obesity) was limited in some of the data sources. Moreover, the limited number of identified ALI cases for the primary and secondary endpoints impacted the multivariable logistic regression strategy. To ensure a sufficient case-to-covariate ratio, the number of covariates and number of categories for categorical covariates included in the models had to be minimised. This resulted in more statistically stable models, but it may have increased the risk of residual confounding. Nevertheless, the restrictive cohort inclusion criteria implemented likely excluded most of the key potential confounders associated with ALI. Moreover, the post hoc analysis that did not impose any exclusion criteria resulted in a much larger number of new users of agomelatine (117,240) and of other antidepressants (4.8 million overall) and yielded more precise OR estimates for the primary endpoint that were consistent with those obtained in the main analysis. Also, control of confounding via multivariable models in those analyses did not have the limitations encountered in the main analysis of the primary endpoint.

The study had important strengths, first of which is that it evaluated more than 3 million (almost 5 million in one of the sensitivity analyses) new users of antidepressants and is the first study of this size to include also a validation component of the cases identified. Second, inclusion of multiple independent data sources and populations from different countries allowed evaluation of the consistency of the findings across five different, heterogeneous, automated, health care data sources. Finally, including three different endpoints with various degrees of PPV and yielding a varying number of cases created different perspectives for interpreting the study results.

5 Conclusion

The results of this study do not suggest that risk of hospitalised ALI with use of agomelatine (compared with use of citalopram) constitutes a public health problem, at least among patient populations in health care systems with prescription patterns and risk minimisation measures similar to those in this study. Thus, it is important to keep in place and comply with the existing risk minimisation measures for agomelatine, which our results suggest are effective in preventing ALI among users of agomelatine. When compared with citalopram, most antidepressants had OR point estimates less than 1.00 for hospitalised ALI. However, uncontrolled sources of bias could explain the results, and specific studies to investigate this potential association of citalopram with ALI are needed.

Notes

The terms “specific” and “nonspecific” are used here to indicate groups of codes that have in previous studies showed more (specific) or less (nonspecific) positive predictive values for ALI.

References

EMA. EPAR summary for the public. Valdoxan (agomelatine). London: European Medicines Agency 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/000915/WC500046224.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2019.

Les Laboratoires Servier. Valdoxan summary of product characteristics. 2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000915/WC500046227.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2019.

Voican CS, Corruble E, Naveau S, Perlemuter G. Antidepressant-induced liver injury: a review for clinicians. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(4):404–15.

Park SH, Ishino R. Liver injury associated with antidepressants. Curr Drug Saf. 2013;8(3):207–23.

Aithal GP, Watkins PB, Andrade RJ, Larrey D, Molokhia M, Takikawa H, et al. Case definition and phenotype standardization in drug-induced liver injury. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):806–15.

Hussaini SH, Farrington EA. Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury: an update on the 2007 overview. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):67–81.

Katz AJ, Ryan PB, Racoosin JA, Stang PE. Assessment of case definitions for identifying acute liver injury in large observational databases. Drug Saf. 2013;36(8):651–61.

Lewer D, O’Reilly C, Mojtabai R, Evans-Lacko S. Antidepressant use in 27 European countries: associations with sociodemographic, cultural and economic factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(3):221–6.

Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;283:1–8.

Breslow RA, Dong C, White A. Prevalence of alcohol-interactive prescription medication use among current drinkers: United States, 1999 to 2010. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(2):371–9.

Du Y, Wolf IK, Knopf H. Psychotropic drug use and alcohol consumption among older adults in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults 2008–2011. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10):e012182.

Rethorst CD, Bernstein I, Trivedi MH. Inflammation, obesity, and metabolic syndrome in depression: analysis of the 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(12):e1428–32.

Chen M, Suzuki A, Borlak J, Andrade RJ, Isabel Lucena M. Drug-induced liver injury: interactions between drug properties and host factors. J Hepatol. 2015;63(2):503–14.

Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA. Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(1):95–106.

Lin ND, Norman H, Regev A, Perahia DG, Li H, Chang CL, et al. Hepatic outcomes among adults taking duloxetine: a retrospective cohort study in a US health care claims database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:134.

Xue F, Strombom I, Turnbull B, Zhu S, Seeger JD. Duloxetine for depression and the incidence of hepatic events in adults. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):517–22.

Pladevall M. Post-authorisation safety study of agomelatine and the risk of hospitalisation for acute liver injury 16/01/2018 2018. http://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=12730. Accessed 2 Mar 2018.

Pladevall M, Rebordosa C, Castellsague J, Perez-Gutthann S, Hellfritzsch M, Hallas J, et al. Post-authorisation safety study of agomelatine and the risk of hospitalisation for acute liver injury 18 May 2017 (Version 2.2) 2017. http://www.encepp.eu/encepp/openAttachment/fullProtocolLatest/19796. Accessed 2 Mar 2018.

SIDIAP. Database. General details. 2019. https://www.sidiap.org/index.php/database/general-details. Accessed 11 Feb 2019.

Prados-Torres A, Poblador-Plou B, Gimeno-Miguel A, Calderon-Larranaga A, Poncel-Falco A, Gimeno-Feliu LA, et al. Cohort profile: the epidemiology of chronic diseases and multimorbidity. The EpiChron Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(2):382–4.

Jobski K, Schmedt N, Kollhorst B, Krappweis J, Schink T, Garbe E. Characteristics and drug use patterns of older antidepressant initiators in Germany. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(1):105–13.

Jobski K, Kollhorst B, Garbe E, Schink T. The risk of ischemic cardio- and cerebrovascular events associated with oxycodone-naloxone and other extended-release high-potency opioids: a nested case-control study. Drug Saf. 2017;40(6):505–15.

Pigeot I, Ahrens W. Establishment of a pharmacoepidemiological database in Germany: methodological potential, scientific value and practical limitations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(3):215–23.

Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–9.

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3.

Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–90.

Pottegard A, Schmidt SA, Wallach-Kildemoes H, Sorensen HT, Hallas J, Schmidt M. Data resource profile: the Danish National Prescription Registry. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):798-f.

Johannesdottir SA, Horváth-Puhó E, Ehrenstein V, Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: the Danish National Database of Reimbursed Prescriptions. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:303–13.

Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M, Martikainen JE, Almarsdottir AB, Sørensen HT. The Nordic countries as a cohort for pharmacoepidemiological research. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;106(2):86–94.

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450.

Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, Leimanis A, Otterblad Olausson P, Bergman U, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(7):726–35.

Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs—I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(11):1323–30.

Forns J, Cainzos-Achirica M, Hellfritzsch M, Giner-Soriano M, Poblador-Plou B, Hallas J, et al. How valid are the codes used to identify acute liver injury (ALI)? A study in 3 European data sources. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(Suppl 2):371 (abstract # 811).

Sikka R, Xia F, Aubert RE. Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(7):449–57.

Kaye JA, Castellsague J, Bui CL, Calingaert B, McQuay LJ, Riera-Guardia N, et al. Risk of acute liver injury associated with the use of moxifloxacin and other oral antimicrobials: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(4):336–49.

Weng HY, Hsueh YH, Messam LL, Hertz-Picciotto I. Methods of covariate selection: directed acyclic graphs and the change-in-estimate procedure. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(10):1182–90.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0, 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org/. Accessed 11 Feb 2019.

Ruigomez A, Brauer R, Rodriguez LA, Huerta C, Requena G, Gil M, et al. Ascertainment of acute liver injury in two European primary care databases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(10):1227–35.

Billioti de Gage S, Collin C, Le-Tri T, Pariente A, Begaud B, Verdoux H, et al. Antidepressants and hepatotoxicity: a cohort study among 5 million individuals registered in the French National Health Insurance Database. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(7):673–84.

Montastruc F, Scotto S, Vaz IR, Guerra LN, Escudero A, Sainz M, et al. Hepatotoxicity related to agomelatine and other new antidepressants: a case/noncase approach with information from the Portuguese, French, Spanish, and Italian pharmacovigilance systems. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34(3):327–30.

Gahr M, Zeiss R, Lang D, Connemann BJ, Hiemke C, Schonfeldt-Lecuona C. Drug-induced liver injury associated with antidepressive psychopharmacotherapy: an explorative assessment based on quantitative signal detection using different MedDRA terms. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56(6):769–78.

Douros A, Bronder E, Andersohn F, Klimpel A, Thomae M, Sarganas G, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: results from the hospital-based Berlin Case-Control Surveillance Study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(6):988–99.

Ferrajolo C, Scavone C, Donati M, Bortolami O, Stoppa G, Motola D, et al. Antidepressant-induced acute liver injury: a case–control study in an Italian inpatient population. Drug Saf. 2018;41(1):95–102.

Jurek AM, Greenland S, Maldonado G. How far from non-differential does exposure or disease misclassification have to be to bias measures of association away from the null? Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(2):382–5.

Lo Re V 3rd, Haynes K, Goldberg D, Forde KA, Carbonari DM, Leidl KB, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes to identify cases of severe acute liver injury in the US Food and Drug Administration’s Mini-Sentinel Distributed Database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(8):861–72.

Maggini M, Raschetti R, Agostinis L, Cattaruzzi C, Troncon MG, Simon G. Use of amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and hospitalization for acute liver injury. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 1999;35(3):429–33.

Traversa G, Bianchi C, Da Cas R, Abraha I, Menniti-Ippolito F, Venegoni M. Cohort study of hepatotoxicity associated with nimesulide and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ. 2003;327(7405):18–22.

Shin J, Hunt CM, Suzuki A, Papay JI, Beach KJ, Cheetham TC. Characterizing phenotypes and outcomes of drug-associated liver injury using electronic medical record data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(2):190–8.

Bui CL, Kaye JA, Castellsague J, Calingaert B, McQuay LJ, Riera-Guardia N, et al. Validation of acute liver injury cases in a population-based cohort study of oral antimicrobial users. Curr Drug Saf. 2014;9(1):23–8.

Lo Re V 3rd, Carbonari DM, Forde KA, Goldberg D, Lewis JD, Haynes K, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and laboratory tests of liver dysfunction to identify acute liver failure events. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(7):676–83.

Udo R, Maitland-van der Zee AH, Egberts TC, den Breeijen JH, Leufkens HG, van Solinge WW, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and laboratory measurements to identify patients with idiopathic acute liver injury in a hospital database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(Suppl 1):21–8.

Jinjuvadia K, Kwan W, Fontana RJ. Searching for a needle in a haystack: use of ICD-9-CM codes in drug-induced liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2437–43.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following people: Estel Plana, MSc (Epidemiology, RTI Health Solutions, Barcelona, Spain), for her support and expertise during the analysis; Carla Franzoni, BSc (Epidemiology, RTI Health Solutions, Barcelona, Spain), for her administrative support; Dr. Niklas Schmedt (InGef - Institute for Applied Health Research, Berlin, Germany), for his involvement in planning the analysis at the beginning of the study; Marieke Niemeyer, MSc (Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology – BIPS, Bremen, Germany) and Sandra Ulrich, MSc (Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology – BIPS, Bremen, Germany), for their contribution to the programming of the analysis datasets; Morten Olesen (Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacy, Department of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark) and Martin Thomsen Ernst (Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacy, Department of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; OPEN, Odense Patient data Explorative Network, Odense University Hospital, Odense Denmark), for their help with data management; Javier Marta, MD [EpiChron Research Group, IACS, IIS Aragon; REDISSEC ISCIII, Miguel Servet University Hospital, Zaragoza, Spain] and Blanca Obón, MD [EpiChron Research Group, IACS, IIS Aragon; REDISSEC ISCIII, Lozano Blesa University Clinic Hospital, Zaragoza, Spain], for their assistance with the clinical validation activities. The authors would also like to thank the German statutory health insurance providers that provided data for the study in GePaRD, namely the AOK Bremen/Bremerhaven, the DAK-Gesundheit, and Die Techniker (TK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors MP, JCa, EJ, ND, and SP planned the study. MP, JCa, and SP conducted the feasibility evaluation and drafted the study protocol. All authors made contributions to the final design and approved the final version of the protocol. Authors AP, TS, JR, BP, JF, MH, TR, DH, MG, AP, JH, LB, and JC undertook the statistical analysis of the different data sources. AT completed the analysis of the external validation study in Germany. JA, MP, JF, and SP completed the analysis and interpretation of the combined (meta-analysis) results with contributions from all authors. MP, JF, MC, and SP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Servier under a contract granting independent publication rights to the research team. Servier co-authors of this manuscript, Emmanuelle Jacquot and Nicolas Deltour, provided feedback and contributed to the design of the study. The sponsor had the opportunity to review the report and contribute to the dissemination of the results. The open access fee was paid by RTI-HS with general funds from the study account, which was funded by Servier.

Conflict of Interest

Manel Pladevall, Joan Forns, Miguel Cainzos-Achirica, Jaume Aguado, Jordi Castellsagué, and Susana Perez-Gutthann are employees of RTI Health Solutions, a unit of RTI International, a nonprofit organisation that conducts work for government, public, and private organisations, including pharmaceutical companies like Servier. Alexandra Prados-Torres and Beatriz Poblador-Plou are members of the EpiChron Research Group on Chronic Diseases of the Aragon Health Sciences Institute (IACS), ascribed to IIS Aragón, and do not have any conflict of interest with this project. Maria Giner-Soriano, Rosa Morros, and Jordi Cortés worked on other projects funded by pharmaceutical companies in their institution that were not related to this study and without personal profit. Tania Schink and Tammo Reinders, as employees of the Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology – BIPS, worked on projects funded by pharmaceutical companies unrelated to this study and without personal profit. Anton Pottegård reports participation in research projects funded by Alcon, Almirall, Astellas, Astra-Zeneca, Novo Nordisk, LEO Pharma, and Servier, all with funds paid to the institution where he was employed (no personal fees) and with no relation to the work reported in this paper. Jesper Hallas has participated in research projects funded by Novartis, Pfizer, Menarini, MSD, Nycomed, LEO Pharma, Almirall, Servier, Astellas, and Alkabello, with grants paid to the institution where he was employed. He has personally received fees for teaching or consulting from the Danish Association of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and from Pfizer and Menarini. Maja Hellfritzsch has received speaker honorarium fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer and a travel grant from LEO Pharma. Johan Reutfors, David Hägg, and Lena Brandt are employees of the Centre for Pharmacoepidemiology, which receives grants from several entities (pharmaceutical companies, regulatory authorities, and contract research organisations) for the performance of drug safety and drug utilisation studies. Gabriel Perlemuter reports participation in research projects funded by Biocodex, Servier, Physiogenex, Gilead, and Pileje as an external expert consultant. He received royalties from Elsevier-Masson, Solar, and John-Libbey and reports travel and participation in meetings funded by Gilead, Abbvie, and Servier. Bruno Falissard has been consultant for E. Lilly, BMS, Servier, Sanofi, GSK, HRA, Roche, Boeringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Almirall, Allergan, Stallergene, Genzyme, Pierre Fabre, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Janssen, Astellas, Biotronik, Daiichi-Sankyo, Gilead, MSD, Lundbeck, Stallergene, Actelion, UCB, Otsuka, Grunenthal, and ViiV. Prof. Antje Timmer participates in a project funded by a consortium of pharmaceutical companies not related to this study and without personal benefit. Nicolas Deltour and Emmanuelle Jacquot are employees of Servier. The statistical analysis was performed by the different research partners in each data source. In EpiChron, the main contributor to the analysis was BP; in SIDIAP, it was JC; in Denmark, it was AP; in GePaRD, the main contributors were TS and TR; and in Sweden, the main contributors were DH and LB. The study protocol is publicly available at the European Union Electronic Register of Post-Authorisation Studies [EU PAS Register # EUPAS10446] [18].

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

The study protocol was registered in the European Medicines Agency electronic Register of Post-Authorisation Studies (EU PAS Register # EUPAS10446).

Dr. Castellsagué is now retired.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pladevall-Vila, M., Pottegård, A., Schink, T. et al. Risk of Acute Liver Injury in Agomelatine and Other Antidepressant Users in Four European Countries: A Cohort and Nested Case–Control Study Using Automated Health Data Sources. CNS Drugs 33, 383–395 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-019-00611-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-019-00611-9