Abstract

Background and Objective

Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic predominantly used in bloodstream infections. Although the prevalence of obesity is increasing dramatically, there is no consensus on how to adjust the dose in obese individuals. In this prospective clinical study, we study the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in morbidly obese and non-obese individuals to develop a dosing algorithm that results in adequate drug exposure across body weights.

Methods

Morbidly obese subjects undergoing bariatric surgery and non-obese healthy volunteers received one intravenous dose of gentamicin (obese: 5 mg/kg based on lean body weight, non-obese: 5 mg/kg based on total body weight [TBW]) with subsequent 24-h sampling. All individuals had a normal renal function. Statistical analysis, modelling and Monte Carlo simulations were performed using R version 3.4.4 and NONMEM® version 7.3.

Results

A two-compartment model best described the data. TBW was the best predictor for both clearance [CL = 0.089 × (TBW/70)0.73] and central volume of distribution [Vc = 11.9 × (TBW/70)1.25] (both p < 0.001). Simulations showed how gentamicin exposure changes across the weight range with currently used dosing algorithms and illustrated that using a nomogram based on a ‘dose weight’ [70 × (TBW/70)0.73] will lead to similar exposure across the entire population.

Conclusions

In this study in morbidly obese and non-obese individuals ranging from 53 to 221 kg we identified body weight as an important determinant for both gentamicin CL and Vc. Using a body weight-based dosing algorithm, optimized exposure across the entire population can be achieved, thereby potentially improving efficacy and safety of gentamicin in the obese and morbidly obese population.

Trial Registration

Registered in the Dutch Trial Registry (NTR6058).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is currently no consensus on how gentamicin should be dosed in obese and morbidly obese individuals. |

In this study with 20 morbidly obese individuals and eight non-obese individuals with body weights from 53 to 221 kg and normal renal function, we found that body weight is an important determinant of gentamicin clearance and central volume of distribution in a two-compartmental model. |

We introduce a novel dose regimen to be used in obese patients with a normal renal function, which is based on an allometric ‘dose weight’ [calculated as 70 × (total body weight/70)0.73] to obtain similar exposure across all body weights up to 215 kg. |

1 Introduction

Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that is frequently used in severe life-threatening infections. Aminoglycosides are widely used antibiotics, predominantly used empirically to expand Gram-negative coverage, although emerging aminoglycoside resistance is a widely recognized threat [1]. Clearly, a favorable outcome can only be achieved with gentamicin if adequate exposure is ensured. For aminoglycosides, a distinct relation between aminoglycoside blood concentrations and both efficacy and toxicity has been reported [2]. Many studies, mostly in vitro and animal in vivo studies, have shown that both the gentamicin maximum (peak) concentrations (Cmax) relative to the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) (Cmax/MIC) and the 24-h free drug area under the concentration–time curve (fAUC24)/MIC is predictive for effectiveness [3,4,5]. While these pharmacodynamic indices are to some extent correlated, the general consensus now is that fAUC24/MIC is the primary pharmacodynamic index for aminoglycosides driving efficacy [2, 6, 7]. Aminoglycoside (nephro- and oto-) toxicity correlates with minimum (trough) concentrations (Cmin) > 1 mg/L [8].

Obesity and morbid obesity, commonly defined as a body mass index (BMI) of > 40 kg/m2, is known to influence different pharmacokinetic parameters such as clearance and volume of distribution, even though exact quantification is still warranted for many drugs [9, 10]. This is especially true for gentamicin, which in normal weight patients is typically dosed on a mg/kg basis [11]. For obese individuals, several dosing strategies have been proposed, mostly based on alternative body size descriptors such as adjusted body weight (ABW). ABW uses a scaling factor for correcting for limited drug diffusion in adipose body tissue [12]. Several studies found that with increasing body weight, ABW was predictive for changes in aminoglycoside volume of distribution [12,13,14,15,16] and therefore for Cmax. More recently, lean body weight (LBW; represents fat-free mass consisting of bone tissue, muscles, organs, and blood volume calculated according to the Janmahasatian formula) was suggested for use in dosing gentamicin, also because of its correlation with volume of distribution [17, 18]. However, as gentamicin exposure drives efficacy, changes in gentamicin clearance are to be taken into account when optimizing drug dosing in the obese. Previous studies report an increase in total body clearance with increasing body weight [12,13,14, 16], with two studies suggesting that ABW might be a predictive covariate for gentamicin clearance [13, 14]. However, compared to current practice, the degree of obesity in these studies was limited, with average body weights that do not exceed 100 kg in most studies. Moreover, many studies rely on sparse sampling from therapeutic drug monitoring, in an era where aminoglycosides were typically dosed three times daily, and, as such, many studies obtained only a limited number of samples up to 8 h post infusion. As a consequence, the exact influence of obesity on the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin, especially clearance, remains yet to be quantified across the current body weights that we are facing in the clinic.

In this prospective clinical study, we study the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in obese and morbidly obese individuals versus non-obese individuals in order to develop a dosing algorithm that can be used across the whole clinical population, and that will lead to similar exposure (area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to 24 h [AUC24]) and optimal Cmin values (< 1 mg/L) in obese individuals compared with their non-obese counterparts.

2 Patients and Methods

2.1 Participants

Morbidly obese patients (BMI above 40 kg/m2 or above 35 kg/m2 with co-morbidities) scheduled to undergo laparoscopic bariatric surgery (either a gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy) and non-obese healthy volunteers (BMI 18–25 kg/m2) were considered for inclusion in this study. Exclusion criteria were a known allergy to aminoglycosides, renal insufficiency (defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] below 60 mL/min based on the Cockcroft-Gault [CG] formula with LBW and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease [MDRD] formula for obese and non-obese individuals, respectively) [18,19,20], pregnancy or breastfeeding, or treatment with potentially nephrotoxic medication in the week before surgery. Before inclusion, participants provided written informed consent. The study was registered in the Dutch Trial Registry (NTR6058), approved by the local human research and ethics committee, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Study Procedures and Data Collection

Morbidly obese patients received a single gentamicin dose of 5 mg/kg LBW (calculated using the Janmahasatian formula [18]), administered intravenously in 30 min, 1–2 h prior to induction of anesthesia. We chose a LBW-based dose regimen for obese individuals because the use of total body weight (TBW) was expected to lead to very high doses and because LBW may be a good body size descriptor for gentamicin dosing [17]. Gentamicin was administered as part of the study protocol, not as part of routine care. Non-obese healthy volunteers received a dose of 5 mg/kg TBW infused over 30 min. Venous blood samples were collected 5, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 360, 720, and 1440 min after end of infusion. Blood samples (3 mL) were collected in lithium-heparin tubes, centrifuged at 1900g for 5 min, and stored at − 80 °C until analysis.

For each patient, data were recorded on body weight, body length, sex, age, and self-reported history/duration of obesity (estimation of number of years the patient fulfils definition of morbid obesity). Serum creatinine was measured and 24-h urine was collected on the study day, with which the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated. In addition, serum creatinine-based GFR estimates were calculated for each patient using either the CG (using LBW for obese and TBW for non-obese individuals, as described before [19]) or MDRD formula (de-indexed for body surface area [BSA]).

For the population pharmacokinetic analysis, BSA was calculated for each individual using the Du Bois–Du Bois formula [21]. ABW was calculated with Eq. (1), as published previously [12]:

where IBW represents ideal body weight in kg, calculated with the Devine formula [22], and TBW represents the TBW in kg. When TBW was smaller than IBW, IBW was imputed as ABW.

2.3 Drug Assay

Total gentamicin plasma concentrations were quantified using a commercially available, validated immuno-assay kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of this assay was 0.4 mg/L and the lower limit of detection (LOD) was 0.3 mg/L.

2.4 Non-Compartmental Statistical Analysis

Individual gentamicin AUC24 was calculated using the trapezoidal rule. Cmax and Cmin were defined as the gentamicin plasma concentration measured at 1 and 24 h after start of infusion, respectively. Categorical data were analyzed by Chi-square test. Continuous data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by t-test when normally distributed or as median ± interquartile range (IQR) and analyzed by Mann-Whitney–Wilcoxon test when not normally distributed. Statistics were performed using R (version 3.4.4) [23]. Differences with a p-value < 0.05 were considered statically significant.

2.5 Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis and Validation

Gentamicin concentrations in both obese and non-obese were analyzed using non-linear mixed-effect modelling (NONMEM® version 7.3 [Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA], Pirana® version 2.9.7, and PsN [Perl-speaks-NONMEM] version 4.6.0) [24, 25]. Concentrations below LLOQ (n = 24/280, 8.6%) were incorporated in the analysis using the M3 method [26].

Model development was done in three stages: (1) definition of the structural model; (2) development of the statistical model; and (3) a covariate analysis. In these steps, discrimination between models was made by comparing the objective function value (OFV, defined by – 2 log likelihood). A p-value of < 0.05, representing a decrease of 3.84 in the OFV value between nested models, was considered statistically significant. Furthermore, goodness-of-fit plots, differences in parameter estimates’ coefficients of variation, or individual plots were evaluated to discriminate between models. Inter-individual variability on parameter estimates was assumed to be log-normally distributed in the population. For residual variability, e.g., resulting from assay errors, model misspecifications or intra-individual variability, a combined additive and proportional error model was investigated.

For the covariate analysis, potentially relevant relations between covariates and pharmacokinetic parameters were visually explored by plotting inter-individual variability estimates independently against the individual covariate values. Covariates that were explored in this manner were TBW, LBW, ABW, BMI, age, sex, GFR, and eGFR (BSA-corrected MDRD or CG using LBW). After visual inspection, potential covariates were separately entered into the model. Continuous covariates were introduced using Eq. 2 for exponential relations and Eq. 3 for linear relations:

where Pi and Pp represent individual and population parameter estimates, COV represents the covariate, COVstandard represents a population standardized (e.g., 70 kg for TBW) or median value for the covariate, X represents the exponent for a power function, and Z is the slope parameter for the linear covariate relationship. Categorical covariates were entered into the model by calculating a separate pharmacokinetic parameter for each category of the covariate. If applicable, it was evaluated whether the inter-individual variability in the parameter concerned decreased upon inclusion of the covariate and whether the plot of the inter-individual variability versus the covariate improved. Additionally, goodness of fit was assessed as described earlier. Using forward inclusion (p < 0.05, OFV decrease > 3.8) and backward deletion (p < 0.001, OFV increase > 10.8), inclusion of the covariate in the final model was justified.

Internal model validation was performed using prediction-corrected visual predictive checks (pcVPCs) and bootstrap resampling analysis [27, 28]. More details of the methods used for model development and internal validation can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

2.6 Model-Based Simulations to Guide Drug Dosing

Using the final model, Monte Carlo simulations were performed in 10,000 patients in a weight range of 50–215 kg for different dose regimens, which included 5 and 7 mg/kg TBW, 5 and 8 mg/kg LBW, 5 mg/kg ABW, and a novel dose nomogram based on the final pharmacokinetic model. In every simulation, gentamicin was administered intravenously over 30 min with 24 h of follow-up. Values for LBW, IBW, and ABW were obtained by resampling data stratified on TBW from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database containing demographic data from a large representative cohort of adults from the USA from 1999 to 2016 [29]. Simulations aimed to target a similar exposure (AUC24) to that in non-obese individuals (< 100 kg) receiving gentamicin in the standard dose of 5 mg/kg TBW and non-toxic Cmin values (< 1 mg/L) in obese individuals.

3 Results

3.1 Patients and Data

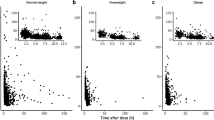

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics of the 20 morbidly obese patients (median body weight 148.8 kg, range 109–221 kg) and eight non-obese individuals (median body weight 72.9 kg, range 53–86 kg) that were included in this study. For each individual, ten samples were obtained, yielding 280 gentamicin plasma concentrations in total. Figure 1 shows the measured plasma concentrations versus time after start of infusion. Both AUC24 and Cmax were lower in morbidly obese individuals administered 5 mg/kg LBW than in non-obese individuals administered 5 mg/kg TBW (AUC24: 43.7 ± 9.7 vs. 68.7 ± 9.5 mg h/L, p < 0.001; Cmax: 8.6 ± 2.2 vs. 17.8 ± 2.6 mg/L, p < 0.001). Cmin levels in all individuals were < 0.5 mg/L.

3.2 Population Pharmacokinetic Model and Validation

A two-compartment model with a combined residual error model best described the data, with inter-individual variability on central volume of distribution (Vc) and clearance (Table 2).

The covariate analysis showed that TBW was the most predictive covariate for both Vc and clearance (p < 0.001 for both). Figure 2 shows the individual estimates for clearance and Vc versus TBW of the included obese and non-obese individuals. Plots for the other covariates are shown in the ESM (Fig. S1). Implementation of TBW with a power function on Vc and clearance led to a reduction in unexplained inter-individual variability from 49.6% to 18.5% for Vc and from 32.2% to 17.4% for clearance. In addition, OFV was found to reduce by 44.4 (p < 0.001) and 30.2 (p < 0.001) points for Vc and clearance, respectively. Implementation of LBW or ABW on Vc was inferior to TBW, even though these covariates significantly improved the base model as well, albeit less convincingly than TBW, with smaller OFV drops (– 19.1 and – 17.3 for LBW on Vc and clearance, – 18.8 and – 21.2 for ABW on Vc and clearance, respectively) and poorer goodness-of-fit diagnostics (data not shown). While no influence of MDRD or CG was visible, GFR seemed to slightly influence clearance, although this correlation disappeared after inclusion of TBW on clearance.

Individual values (n = 28) for a central volume of distribution (in L) and b clearance (in L/min) versus total body weight from the base model. The black line represents the covariate relation as implemented in the final model (Table 2). CL clearance, TBW total body weight, Vc central volume of distribution

According to the final model (Table 2), Vc and clearance are best described using Eqs. (4) and (5):

where Vc,i and CLi are the Vc and clearance of the ith individual, respectively. TBWi is the TBW of the ith individual. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on the bootstrap resampling (Table 2) are shown in brackets.

The parameter estimates of the final model are shown in Table 2. Goodness-of-fit plots of the final model are presented in the ESM (Fig. S2).

For internal validation, stratified pcVPCs for obese and non-obese individuals are shown in Fig. 3 and show good predictive performance for both groups where CIs for the median and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of observed and model-simulated data are in good agreement. The results of the bootstrap analysis confirmed the model parameters and robustness of the model and are presented in Table 2.

Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks of the final model for non-obese (upper left panel) and obese (upper right panel) individuals. The observed concentrations are shown as black circles; the median and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the observed data are shown as the solid and lower and upper dashed lines, respectively. The gray shaded areas show the 95% confidence intervals of the median (dark gray) and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles (light gray) of the simulated concentrations (n = 1000) based on the original dataset. Lower panels show the observed proportion below the limit of quantification (black dots), where shaded areas represent the 95% confidence interval of the proportion based on the simulated concentrations (n = 1000). LOQ limit of quantification

3.3 Model-Based Simulations with Different Dose Regimens

Figure 4 shows the median and 95% CI for the AUC24 (upper panel) and Cmin (lower panel) with different dosing regimens for individuals with a weight range of 50–215 kg based on Monte Carlo simulations. The median AUC24 in non-obese individuals (< 100 kg) receiving gentamicin at a commonly prescribed dose of 5 mg/kg TBW represents the target for gentamicin exposure (depicted as horizontal dashed line.

Boxplots (median and 95% confidence interval) representing gentamicin AUC24 (upper panel) and Cmin (lower panel) for different weight categories based on Monte Carlo simulations with six different TBW-, LBW- (calculated with the Janmahasatian formula [18]), and ABW [calculated as IBW + 0.4 × (TBW – IBW)]-based dosing regimens (n = 10,000 per regimen). The proposed nomogram is based on a ‘dose weight’ calculated as 70 × (TBW/70)0.73 (shown in Table 3). The dashed line represents the median value of 5 mg/kg TBW in the < 100 kg group as a target reference for AUC24 (upper panel) or 1 mg/L as a target reference for Cmin (lower panel). ABW adjusted body weight, AUC24 area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to 24 h, Cmin minimum (trough) concentration, LBW lean body weight, TBW total body weight

Figure 4 (upper panel) illustrates that a dose based on LBW (i.e., 5 or 8 mg/kg LBW) leads to a decrease in AUC24 with increasing body weight. In contrast, dosing based on TBW (depicted for 5 and 7 mg/kg) leads to higher AUC24 values with increasing body weight. The use of ABW (5 mg/kg) results in a similar AUC24 across body weights as that of the reference < 100 kg group, with a slight trend towards a decreased AUC24 with increasing body weight. When a dose regimen based the equation for clearance of the final model [i.e., an allometric ‘dose weight’, which is calculated as 70 × (TBW/70)0.73; Table 3] is used, a similar AUC24 to that of the reference group is yielded across all weight ranges up to 215 kg.

For all dose regimens and weight ranges, gentamicin Cmin values were below the limit of 1 mg/L (Fig. 4, lower panel). Results for Cmax are shown in Fig. S3 in the ESM, showing that a TBW-based dose regimen yields similar Cmax values across body weights.

4 Discussion

In this study, we have successfully developed a population pharmacokinetic model for gentamicin based on full pharmacokinetic curves obtained in individuals with body weights ranging from 53 to 221 kg. Our study shows that in obese individuals, both gentamicin clearance and Vc are significantly influenced by body weight. These findings can be used as guide for dosing in the ever-increasing group of obese and morbidly obese patients.

Our study shows that gentamicin clearance increases with TBW. From the studies investigating the pharmacokinetics of aminoglycosides in obesity [12, 14,15,16,17, 30, 31], four papers reported an increase in clearance in obese patients [12,13,14, 16] and two studies found ABW as a predictive covariate [13, 14]. In these studies participants were only moderately obese (average body weights around 80–100 kg with SDs around 15–20 kg). Moreover, at the time these studies were conducted, aminoglycosides were typically dosed in regimens of up to three times daily, and as such many studies obtained samples up to 8 h post infusion only, thereby limiting the estimation of gentamicin clearance and the prediction of 24-h exposure and Cmin values. In this respect, we believe that our study is an important addition to the existing literature, since we were able to sample up to 24 h post infusion (instead of 8 h) in a wide range of body weights (53–221 kg) and, combined with using state-of-the-art modelling techniques, we could for the first time accurately assess gentamicin clearance and its covariates in the obese population.

An important question is how the finding that clearance changes with body weight in obese individuals can be explained. The exponent of 0.73 (95% CI 0.57–0.90) we identified for the change with weight is comparable to the value of 0.75 which has been reported as a value that describes the influence of size on clearance in allometry theory [32]. However, it is debatable whether an increase in weight resulting from obesity can be compared with an increase in weight because of an increase in size [32]. For other drugs that were studied in obese patients, many show unchanged clearance with increasing weight, even when morbidly obese patients were included [33,34,35]. The increase in gentamicin clearance with body weight we identify in this study could potentially be explained by a larger GFR in obese individuals and/or an increase in organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) activity as gentamicin was reported to be a substrate for OCT2 [36]. With respect to GFR, it is emphasized that in our study only individuals with a GFR > 60 mL/min were included. In our study, weight was the most important covariate, and after implementation of weight, no additional influence of GFR could be identified, even though the GFR range in our population was large (110–230 mL/min). While this does not preclude GFR being the explanation for the observed increase in gentamicin clearance in the obese, and also for other renally excreted drugs such as cefazoline, no increase in clearance with increasing weight was found when studied in morbidly obese and non-obese individuals [35, 37]. As such, perhaps the increased activity in OCT2 that was reported in overfed rats and that led to increased gentamicin uptake in renal tubular cells [36] may be considered as an explanation for the findings of our study. In line with this hypothesis, for metformin, which is known to be secreted by OCT2 in the tubulus, a larger clearance was found in obese adolescents (1.17 L/min) than in non-obese children (0.55 L/min), which was also explained by a higher OCT2-mediated tubular secretion of metformin in obese individuals [38]. From these results it seems that more basic research is needed to identify the exact cause of our findings.

Furthermore, our study demonstrates that Vc best correlates with body weight. Earlier studies with aminoglycosides in obese patients found ABW or LBW to correlate with volume of distribution [12,13,14, 17, 30]. In our study we obtained a large number of samples over a 24-h window, including samples that were taken shortly after infusion (i.e., 5, 30, 60, and 90 min after infusion). This study design allows us to fully describe the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in detail. Most of the previously published studies were performed with sparse (therapeutic drug monitoring) data with only a few samples taken shortly after infusion and consequently analyzed by non-compartmental analysis, thereby complicating exact estimation of the volume of distribution. While the detailed information resulting from our sampling scheme and advanced modelling strategy justifies the conclusions regarding changes of volume of distribution with weight, the results challenge the common assumption that only limited changes in volume of distribution are to be expected for hydrophilic drugs such as gentamicin. It therefore seems that lipophilicity alone is a poor predictor of how volume of distribution changes with increasing body weight, as was demonstrated in several recent reviews [9, 39].

Based on the results of our study, we propose administration of gentamicin using a practical dose nomogram (Table 3) that is based on a body weight-derived allometric ‘dose weight’ [i.e., 70 × (TBW/70)0.73] and is derived from the allometric relationship between clearance (driving AUC) and TBW (Table 2, Eq. 5). Considering fAUC24/MIC as the primary pharmacodynamic index for aminoglycoside treatment, our dosing nomogram yields a similar gentamicin exposure (AUC24) across all weights with all Cmin values < 1 mg/L (Fig. 4). In clinical practice, the nomogram can easily be implemented to select the initial gentamicin dosage, after which dose individualization may be employed by estimating the individual’s gentamicin clearance. This is typically done using therapeutic drug monitoring (where one or two samples are taken during the β-elimination phase, for instance between 2 and 8 h post infusion) in combination with Bayesian software employed with a suitable population pharmacokinetic model. The population pharmacokinetic model presented in the current paper could be used for this purpose. Alternatively, for example when such software is unavailable, other approaches have been suggested to individualize gentamicin drug treatment [7].

Figure 4 also illustrates that ABW- and LBW-based dose regimens show trends towards a lower exposure with increasing body weight. Despite these trends across weight, it seems that 8 mg/kg LBW and 5–6 mg/kg ABW could be considered as alternatives for our nomogram because using these doses in the median range of the morbidly obese population leads to rather similar AUC24 values. Implementation of LBW, and to a lesser extend ABW, has, however, been hampered by the complexity of the calculations, which is why we came up with our nomogram, as depicted in Table 3.

Some limitations may apply to our results. First, individuals in our study were, besides (some) being overweight, otherwise healthy, relatively young, and had no renal impairment. As a consequence, renal dysfunction in the obese could not be studied, while in non-obese patients gentamicin clearance has been reported to be dependent on renal function [40]. Also, drug pharmacokinetics have been shown to be influenced by critical illness [41]. Therefore, further refinement of our model is warranted for use in obese patients with renal impairment, critical illness, and/or older age. Still, we believe that the dose recommendations from the current study can be a valuable starting point for dosing of obese patients with renal impairment or critical illness. Second, in the current study we did not study the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin after significant reduction in body weight following bariatric surgery. It has been shown for the benzodiazepine midazolam that the pharmacokinetics in these individuals are different to those in individuals with the same body weight without a history of obesity [42]. Third, we did not include individuals with a BMI 25–35 kg/m2. However, based on the relationship between TBW and clearance and Vc, as depicted in Fig. 2, we think it is justified to conclude that the pharmacokinetics will not be any different in these individuals. Last, the obese individuals in our study underwent bariatric surgery during the study procedures, which in theory might influence pharmacokinetics. In our hospital, bariatric surgery is performed laparoscopically, with a short procedure (usually 30–45 min) involving minimal blood loss (usually < 50 mL). Also, hemodynamics were tightly monitored and regulated during surgery. No major hemodynamic instability was recorded for any of the included individuals in our study. For this reason, we expect that the influence of surgery on the pharmacokinetics is negligible.

5 Conclusion

We show that gentamicin clearance increases with body weight according to a power function with an exponent of 0.73. As we found that the current worldwide deployed dosing strategy of dosing on LBW or ABW may lead to lower exposure with increasing bodyweight, we propose the use of a dose nomogram on an allometric ‘dose weight’ [calculated as 70 × (TBW/70)0.73; Table 3] for dosing gentamicin in (morbidly) obese patients > 100 kg to obtain similar exposure across all body weights up to 215 kg.

References

EUCAST. Gentamicin: rationale for the EUCAST clinical breakpoint (version 1.2). 2009. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Rationale_documents/Gentamicin_rationale_1.2_0906.pdf. Accessed 2 Apr 2019.

USCAST: United States Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Aminoglycoside in vitro susceptibility test interpretive criteria evaluations, version 1.1. USCAST; 2016. http://www.uscast.org/. Accessed May 2018.

Vogelman B, Gudmundsson S, Leggett J, Turnidge J, Ebert S, Craig WA. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetics parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:831–47.

Moore RD, Smith CR, Lietman PS. Association of aminoglycoside plasma levels with therapeutic outcome in gram-negative pneumonia. Am J Med. 1984;77:657–62.

Mouton JW, Jacobs N, Tiddens H, Horrevorts AM. Pharmacodynamics of tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;52:123–7.

Turnidge J. Pharmacodynamics and dosing of aminoglycosides. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:503–28.

Pai MP, Rodvold KA. Aminoglycoside dosing in patients by kidney function and area under the curve: the Sawchuk-Zaske dosing method revisited in the era of obesity. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78:178–87.

Prins JM, Büller HR, Kuijper EJ, Tange RA, Speelman P. Once versus thrice daily gentamicin in patients with serious infections. Lancet. 1993;341:335–9.

Smit C, De Hoogd S, Brüggemann RJM, Knibbe CAJ. Obesity and drug pharmacology: a review of the influence of obesity on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018;14:275–85.

Brill MJE, Diepstraten J, Van Rongen A, Van Kralingen S, Van den Anker JN, Knibbe CAJ. Impact of obesity on drug metabolism and elimination in adults and children. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51:277–304.

Polso AK, Lassiter JL, Nagel JL. Impact of hospital guideline for weight-based antimicrobial dosing in morbidly obese adults and comprehensive literature review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39:584–608.

Bauer LA, Edwards WAD, Dellinger EP, Simonowitz DA. Influence of weight on aminoglycoside pharmacokinetics in normal weight and morbidly obese patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;24:643–7.

Leader WG, Tsubaki T, Chandler MH. Creatinine-clearance estimates for predicting gentamicin pharmacokinetic values in obese patients. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1994;51:2125–30.

Schwartz SN, Pazin GJ, Lyon JA, Ho M, Pasculle AW. A controlled investigation of the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin and tobramycin in obese subjects. J Infect Dis. 1978;138:499–505.

Sketris I, Lesar T, Zaske DE, Cipolle RJ. Effect of obesity on gentamicin pharmacokinetics. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:288–93.

Traynor AM, Nafziger AN, Bertino JS. Aminoglycoside dosing weight correction factors for patients of various body sizes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:545–8.

Pai MP, Nafziger AN, Bertino JS. Simplified estimation of aminoglycoside pharmacokinetics in underweight and obese adult patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4006–11.

Janmahasatian S, Duffull SB, Ash S, Ward LC, Byrne NM, Green B. Quantification of lean bodyweight. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:1051–65.

Demirovic JA, Pai AB, Pai MP. Estimation of creatinine clearance in morbidly obese patients. Am J Heal Syst Pharm. 2009;66:642–8.

Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:247–54.

Du Bois D, Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Intern Med. 1916;17:863–71.

McCarron M, Devine B. Gentamicin therapy. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1974;8:650–5.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015.

Keizer RJ, Karlsson MO, Hooker A. Modeling and simulation workbench for NONMEM: tutorial on Pirana, PsN, and Xpose. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2:e50.

Beal SL, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann A. NONMEM user’s guide. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco; 1999.

Beal SL. Ways to fit a PK model with some data below the quantification limit. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2001;28:481–504.

Bergstrand M, Karlsson MO. Handling data below the limit of quantification in mixed effect models. AAPS J. 2009;11:371–80.

Bergstrand M, Hooker AC, Wallin JE, Karlsson MO. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. AAPS J. 2011;13:143–51.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (NHANES) 1999–2016. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx. Accessed Aug 2018.

Korsager S. Administration of gentamicin to obese patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1980;18:549–53.

Blouin RA, Mann HJ, Griffen WO, Bauer LA, Record KE. Tobramycin pharmacokinetics in morbidly obese patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1979;26:508–12.

Eleveld DJ, Proost JH, Absalom AR, Struys MMRF. Obesity and allometric scaling of pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50:751–6.

De Hoogd S, Välitalo PAJ, Dahan A, van Kralingen S, Coughtrie MMWW, van Dongen EPAA, et al. Influence of morbid obesity on the pharmacokinetics of morphine, morphine-3-glucuronide, and morphine-6-glucuronide. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56:1577–87.

Brill MJE, Van Rongen A, Houwink API, Burggraaf J, Van Ramshorst B, Wiezer RJ, et al. Midazolam pharmacokinetics in morbidly obese patients following semi-simultaneous oral and intravenous administration: a comparison with healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53:931–41.

van Kralingen S, Taks M, Diepstraten J, Van De Garde EM, van Dongen EP, Wiezer MJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics and protein binding of cefazolin in morbidly obese patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:985–92.

Gai Z, Visentin M, Hiller C, Krajnc E, Li T, Zhen J, et al. Organic cation transporter 2 overexpression may confer an increased risk of gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:5573–80.

Brill MJE, Houwink API, Schmidt S, Van Dongen EPA, Hazebroek EJ, Van ramshorst B, et al. Reduced subcutaneous tissue distribution of cefazolin in morbidly obese versus non-obese patients determined using clinical microdialysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:715–23.

van Rongen A, van der Aa MP, Matic M, van Schaik RHN, Deneer VHM, van der Vorst MM, et al. Increased metformin clearance in overweight and obese adolescents: a pharmacokinetic substudy of a randomized controlled trial. Paediatr Drugs. 2018;20:365–74.

Jain R, Chung SM, Jain L, Khurana M, Lau SWJ, Lee JE, et al. Implications of obesity for drug therapy: limitations and challenges. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:77–89.

Matzke GR, Jameson JJ, Halstenson CE. Gentamicin disposition in young and elderly patients with various degrees of renal function. J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;27:216–20.

Tängdén T, Ramos Martín V, Felton TW, Nielsen EI, Marchand S, Brüggemann RJ, et al. The role of infection models and PK/PD modelling for optimising care of critically ill patients with severe infections. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1021–32.

Brill MJ, Van Rongen A, Van Dongen EP, Van Ramshorst B, Hazebroek EJ, Darwich AS, et al. The pharmacokinetics of the CYP3A substrate midazolam in morbidly obese patients before and one year after bariatric surgery. Pharm Res. 2015;32:3927–36.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all study participants for participating and Ingeborg Lange, Angela Colbers, Brigitte Bliemer, and Sylvia Samson for the help with inclusion of study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All participants provided written informed consent. The study was registered in the Dutch Trial Registry (NTR6058), approved by the local human research and ethics committee, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of Interest

Roger J.M. Brüggemann declares that he has no conflicts of interest with regards to this work. Outside of this work, he has served as consultant to and has received unrestricted research grants from Astellas Pharma Inc., F2G, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharpe and Dohme Corp., and Pfizer Inc. All payments were invoiced by the Radboud University Medical Center. Cornelis Smit, Roeland E. Wasmann, Sebastiaan C. Goulooze, Eric J. Hazebroek, Eric P.A. Van Dongen, Desiree M.T. Burgers, Johan W. Mouton, and Catherijne A.J. Knibbe declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was funded by ZonMW (grant number 836041004).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Smit, C., Wasmann, R.E., Goulooze, S.C. et al. A Prospective Clinical Study Characterizing the Influence of Morbid Obesity on the Pharmacokinetics of Gentamicin: Towards Individualized Dosing in Obese Patients. Clin Pharmacokinet 58, 1333–1343 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-019-00762-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-019-00762-4