Abstract

Successful treatment for respiratory diseases relies on effective delivery of medication to the lungs using an inhalation device. Different inhalers have distinct characteristics affecting drug administration and patient adherence, which can impact clinical outcomes. We report on the development of the Respimat® soft mist inhaler (SMI) and compare key attributes with metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) and dry powder inhalers (DPIs). The Respimat SMI, a pocket-sized device generating a single-breath, inhalable aerosol, was designed to enhance drug delivery to the lungs, reduce the requirements for patient coordination and inspiratory effort, and improve the patients’ experience and ease of use. The drug deposition profile with Respimat SMI is favorable compared with MDIs and DPIs, with higher drug deposition to the lung and peripheral airways. The slow velocity and long spray duration of the Respimat SMI aerosol also aid patient coordination. Clinical equivalence has been demonstrated for maintenance treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using once-daily tiotropium between Respimat SMI (5 µg) and HandiHaler DPI (18 µg). In comparative studies, patients preferred Respimat SMI to MDIs and DPIs; they reported that Respimat SMI was easy to use and felt the inhaled dose was delivered. The Respimat SMI, designed to generate a slow-moving and fine mist, is easy to use and effectively delivers drug treatment to the lungs. The patient-centered design of Respimat SMI improved patient satisfaction, and may help to promote long-term adherence and improve clinical outcomes with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Respimat soft mist inhaler (SMI) was designed to enhance drug delivery to the lungs, reduce the requirements for patient coordination and inspiratory effort, and improve patients’ experience and ease of use. |

With Respimat SMI, lung deposition of drug is high and oropharyngeal deposition is low. |

Respimat SMI is easy for patients to use correctly and is associated with a high rate of patient preference and adherence and a low rate of discontinuation. |

1 Introduction

The delivery of respiratory medication by inhalation device is critical to the management of pulmonary diseases [1, 2]. The inhalers used today for the delivery of drugs directly to the lungs are based on a long history of development. Here we briefly describe the development of inhalers and how more recent research has guided inhaler design. We use the Respimat® soft mist inhaler (SMI; Boehringer Ingelheim International GmBH, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) as an illustration of how design changes based on the feedback received from patients and healthcare providers have been implemented for real-world use. In addition to the inhaler’s technical aspects, we also focus on patient perspectives when using this device, and a comparison of clinical efficacy against a dry powder inhaler (DPI), the Handihaler® (Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany).

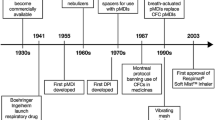

Innovative inhalers and aerosol drug discoveries have significantly improved the quality of life (QoL) of patients with pulmonary diseases [3]. The delivery of therapeutic aerosols began over 3000 years ago, but it was in the 1950s, with the introduction of the metered-dose inhalers (MDIs), that the pharmaceutical aerosol industry was modernized (Fig. 1) [3, 4].

The development of inhalers (adapted from [6]). CFC chlorofluorocarbon, DPI dry powder inhaler, HFA hydrofluoroalkane, pMDI pressurized metered-dose inhaler

The development of pressurized MDIs in 1956 revolutionized the treatment of lung diseases, providing truly convenient and portable treatment that effectively controlled symptoms of pulmonary diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [3, 5, 6]. Given their ability to deliver drugs to the lungs quickly and effectively, MDIs rapidly became the treatment of choice over earlier nebulizer designs [3]. Although simple DPIs were available from the mid-19th century, it was not until the late 1960s that breath-actuated DPIs were developed (Fig. 1) [3, 4].

Since the 1970s, the use of inhalers for pulmonary drug delivery has become more widespread, and recent research and development into inhaler evolution has focused on optimizing drug delivery to the lungs [7] through improvements to devices, and also via more sophisticated formulations that disperse easily in the inhaled air-stream [8].

Correct use of an inhaler is a key contributing factor for effective pulmonary disease management [1, 2]. Different inhaler types have distinct attributes [9, 10], some of which can affect patient satisfaction and adherence [11, 12], thereby impacting clinical outcomes [13]. Pulmonary disease-management guidelines recommend that inhaled therapy be individualized for each patient, with regular monitoring of inhaler technique [1, 2], yet the majority of patients with asthma or COPD do not use their inhalers correctly [14], which can lead to poor disease management, causing increased healthcare costs [15].

Although MDIs and DPIs are effective and convenient methods for drug delivery and symptom relief, their efficacy is user dependent. For optimal drug delivery using an MDI, the patient needs to coordinate and synchronize actuation and inhalation, while DPIs are dependent on speed of inhalation (specifically, the initial acceleration of the inhalation maneuver), the inhaled volume, and inspiratory effort [6, 9, 16,17,18]. Patients with cognitive impairment or limited manual dexterity and those with reduced inspiratory flow rate may be unable to effectively use an MDI or DPI [19]. Therefore, there is a requirement for inhalers that overcome the difficulties patients may have in using MDIs and DPIs. Here we describe the Respimat SMI as an example of how inhalers have evolved in recent years.

2 Development and Delivery Characteristics of Respimat SMI

The Respimat SMI was developed with the characteristics of an ideal inhaler (Table 1) and the need for a pocket-sized device that can generate a single-breath, inhalable aerosol from a drug solution in mind (Fig. 2a) [20].

The main goals of developing the Respimat SMI were to: avoid the use of propellants; reduce the requirements for patient inspiratory effort; enhance drug delivery; and improve patient usability [20]. Based on user feedback, the Respimat SMI was designed to include several features to improve usability (Fig. 2b).

To avoid the use of propellants, the effective aspects of nebulizer technology were applied to generate an aerosol inhalant, or “soft mist,” from liquid [6, 21]. Respimat SMI uses an extremely fine nozzle system, the Uniblock, to aerosolize a metered dose of drug solution into tiny particles suitable for inhalation [6, 21,22,23]. The mechanics of the device are designed to optimize aerosol velocity, particle size, and internal resistance in order to enhance drug delivery into the airways [6, 20]. Importantly, Respimat SMI actively generates an aerosol independently of the patient’s inhalation effort, with a slow velocity and prolonged duration, which facilitates the coordination of actuation and inhalation [6, 20].

Because the aerosol generated by Respimat SMI has a high fine-particle fraction delivered at a slow velocity, lung deposition is maximized and oropharyngeal deposition minimized, even at low inhalation flows [6, 20, 24, 25]. More than 60% of the drug dose released by Respimat SMI falls within a fine-particle dose of ≤ 5.0 μm, which enhances drug delivery to the smaller bronchi and bronchioles [6].

Compared with MDIs and DPIs, Respimat SMI has a favorable lung deposition profile (Fig. 3) in patients with asthma or COPD, as well as in healthy volunteers [26,27,28,29]. Iwanaga et al. [26] reported that, in six patients with asthma, drug deposition to the whole lung and the peripheral airways using Respimat SMI (57.1% and 39.7%, respectively) was higher than when using MDIs or DPIs (whole lung deposition 20.0–44.3%; peripheral airway deposition 11.3–29.2%; Fig. 4) by functional respiratory imaging [26]. The deposition fractions for Respimat SMI in the upper, central, and peripheral airways were in the ranges 41.3–44.3%, 13.8–22.6%, and 34.6–42.4%, respectively [26].

Particle deposition imaging of an inhaled LABA and a LAMA, by inhalation device [26]. Each inhalation device contains the following bronchodilators: Flutiform, formoterol (LABA); Symbicort, formoterol (LABA); Relvar, vilanterol (LABA); Spiriva Respimat, tiotropium (LAMA). All images were taken from the same subject. LABA long-acting β2 agonist, LAMA long-acting muscarinic antagonist. Reproduced with permission from Iwanaga et al. [26]

Adapted with permission from Iwanaga et al. [26]

Drug deposition fraction of an inhaled LABA and a LAMA, by inhalation device: a in the entire lung; b in the peripheral airways [26]. Each inhalation device contains the following bronchodilators: Flutiform, formoterol (LABA); Symbicort, formoterol (LABA); Relvar, vilanterol (LABA); Spiriva Respimat, tiotropium (LAMA). Box shows the upper quartile, median and lower quartile; whiskers show the maximum and minimum values. BD bronchodilator, LABA long-acting β2 agonist, LAMA long-acting muscarinic antagonist, LUNG whole lung, PERI peripheral airway.

DPIs use inhaled air to disaggregate and disperse the powder into the airstream, so each DPI has an inherent level of resistance associated with the dispersal mechanism [30]. Most DPIs require a high inspiratory flow to overcome the device resistance and achieve effective drug delivery, which can be an issue for some patients, such as the elderly or those with COPD, who may not be capable of generating a sufficient inspiratory flow rate [31]. Pitcairn and colleagues evaluated the lung deposition of drugs inhaled via the Respimat SMI or an MDI at an average inspiratory flow rate of 30 L/min compared with via a DPI at a target peak inspiratory flow rate of 30 or 60 L/min [27]. Regardless of whether inhalation through the DPI was fast or slow, the lung deposition profile was worse with the DPI than with either the Respimat SMI or the MDI, with a smaller proportion of the drug reaching the outer lungs and more deposited in the central zones after DPI administration [27]. In addition, an in vitro mouth–throat deposition model of COPD showed that Respimat SMI delivered a greater modeled dose to the lung (mDTL) than the Breezhaler (59% mDTL with a moderate COPD breathing pattern and 67% mDTL with a very severe COPD breathing pattern with the Respimat SMI vs. 43% and 51%, respectively, for the Breezhaler) [32].

Part of the reason for the improved deposition in the lungs and reduced oropharyngeal deposition may be the slower aerosol velocity of Respimat SMI relative to other inhalers [6, 20]. Studies have shown that the aerosol spray velocity of the Respimat SMI (0.84 and 0.72 m/s at 80 and 100 mm from the end of the nozzle, respectively) is lower than that of seven different MDIs; the slowest MDI spray velocity was 2.47 and 1.71 m/s at 80 and 100 mm from the end of nozzle, respectively [33]. Similarly, the Respimat SMI produces an aerosol cloud that moved much more slowly than aerosol clouds from MDIs (mean velocity 100 mm from the nozzle: Respimat SMI, 0.8 m/s; MDIs, 2.0–8.4 m/s). The soft mist produced by the Respimat SMI had a longer mean duration (1.5 s) than that produced by MDIs (0.15–0.36 s) [24].

3 Clinical Equivalence Between Respimat SMI and HandiHaler

Two devices, the HandiHaler DPI and the Respimat SMI, are available for the delivery of long-acting tiotropium maintenance treatment. The HandiHaler (approved in Europe in 2002 and in the USA and Japan in 2004) has been available for longer than the Respimat SMI (Europe 2007; Japan 2010; USA and Canada 2014) [34, 35], which may explain why it is more commonly prescribed [36, 37]; however, the use of the Respimat SMI is increasing [37]. The HandiHaler DPI delivers tiotropium at a licensed dose of 18 μg once daily (QD) [34, 38], whereas the efficiency of drug delivery with Respimat SMI has meant that a lower dose of tiotropium 5 µg QD is required with Respimat SMI. Despite the differences in dose between the two inhalers, direct comparative studies suggest that the efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety of tiotropium delivered at a dose of 5 μg QD by Respimat SMI is comparable with that of tiotropium 18 µg QD delivered by the HandiHaler [38,39,40].

In a pooled analysis of two 30-week, double-blind, double-dummy, crossover studies in patients with COPD (N = 207), lung function improvement [as measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)] with tiotropium 5 μg QD delivered by Respimat SMI was noninferior to tiotropium 18 μg QD delivered by HandiHaler (mean trough FEV1 response vs. HandiHaler: 0.029 L; p < 0.0001) [39].

The efficacy and safety of tiotropium 5 µg QD Respimat SMI versus tiotropium 18 μg QD HandiHaler were also investigated in a 4-week, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, two-way crossover study in Japanese COPD patients (N = 157). Lung function improvements demonstrated treatment with tiotropium via Respimat SMI was noninferior to HandiHaler (mean trough FEV1 response vs. HandiHaler: 0.008 L; p < 0.001). The incidence of adverse events was similar with Respimat SMI (31%) and HandiHaler (28%) [38].

A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study in patients with COPD (TIOSPIR trial; N = 17,135) also evaluated the safety and efficacy of tiotropium via Respimat SMI 5 μg QD compared with tiotropium HandiHaler 18 μg QD. Respimat SMI was noninferior to HandiHaler with respect to the risk of death (hazard ratio (HR) 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.84–1.09) and comparable with HandiHaler with respect to the risk of first exacerbation (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.93–1.03). Treatment with tiotropium using Respimat SMI had a safety profile and exacerbation efficacy similar to those with tiotropium using HandiHaler [40].

4 Patient Perspectives

Regardless of the technical advantages a device may confer, if patients do not find the inhaler intuitive and easy to use, then adherence may be reduced and poorer symptom control is likely to occur [11, 13]. Key factors determining inhaler choice that have been identified by European respiratory experts are the ability of the patient to handle the inhaler, the patient’s experience with the inhaler, the patient’s ability to coordinate their actions, their ability to learn to use the device correctly, and the cost of the device [41].

As described earlier, the Respimat SMI was designed not only to enhance drug delivery without the use of propellants, but also to allow reliable drug delivery via a device that was easy for patients to use. For example, the internal mechanism of Respimat SMI propels the medication into the lungs without patients having to generate high inspiratory flow, as is required for some DPIs. The slow velocity of the aerosol generated by the Respimat SMI and the longer spray duration relative to MDIs provides the patient with more “time to breathe,” so that they do not need to coordinate inhaler actuation and inhalation as closely, or generate as much inspiratory effort, to achieve effective drug deposition [24].

4.1 Ease of Use

A survey of 503 patients with COPD asked patients to rank the attributes of an inhaler that are most important to them, and patients consistently rated performance characteristics of the inhaler ahead of convenience characteristics on the Patient Satisfaction and Preference Questionnaire (PASAPQ) [42]. In fact, the three most important inhaler attributes were all performance characteristics: “Feeling that your medicine gets into your lungs,” “Inhaler works reliably,” and “Inhaler makes inhaling your medicine easy.” This survey found that the Respimat SMI scored highly in both performance and convenience domain scores on the PASAPQ questionnaire (median 81.0 for performance and 83.0 for convenience) [42]. A number of other studies in patients with COPD or asthma have similarly reported that the Respimat SMI was easy for patients to use and inhale a dose, and that the inhaled dose was felt by patients to be going to the lungs [43, 44].

Ease of use is particularly important for patients with COPD, many of whom are elderly and have manual dexterity issues, cognitive impairment, or co-morbidities [45]. As described earlier, many patients with COPD have difficulty obtaining the required inspiratory flow rate to achieve effective drug delivery with DPIs, and peak inspiratory flow rate decreases with age and worsening disease severity [31]. Older age has also been shown to be associated with worsening inhaler technique [46]. In this respect, the Respimat SMI has many features that are useful for older patients, including the simplicity of preparing a dose, the ability to obtain drug delivery at low inspiratory flow rates, and the fact that minimal manual dexterity is required to initiate administration [41, 45]. Possible disadvantages of the Respimat SMI are that the device needs some basic assembly and priming before the first use [6], and tends to cost more than older inhalers, which can be a consideration for some patients [43].

Similarly, ease of use is also particularly important in young children; it is common for children to use inhalers incorrectly and this can result in reduced or negligible benefit [47]. Children may also find it difficult to produce adequate airflow to correctly operate some inhalers [47]. In a study in children (aged < 5 years) with respiratory disease, 83% of 4-year-olds achieved adequate inhalation using Respimat SMI unaided or with parental help, and 100% of 3- to 4-year-olds achieved adequate inhalation with the addition of a valved holding chamber [47].

Several other studies show that the Respimat SMI is easy for patients to use and that patients with asthma or COPD master the correct inhaler technique rapidly after training [48, 49]. This may be particularly important for older patients who have more difficulty learning the correct technique for using a new inhaler [46]. Dal Negro and Povero compared the ease and speed with which patients learned to use Respimat SMI compared with the Genuair MDI and the Breezhaler DPI [48, 49]. Patients mastered the correct inhaler technique for Genuair and Respimat SMI significantly more quickly than for Breezhaler. Moreover, the rapid acquisition of the correct inhaler technique was estimated to save time and money associated with nurse training time [49].

Given that it is easy to use, it is expected that the Respimat SMI will become at least as popular as the MDIs and DPIs; however, as mentioned above, the Respimat SMI has been on the market for a relatively short period of time [34] compared with the other devices.

4.2 Adherence

Inhaler characteristics may affect patient adherence [50], but it is almost impossible to study the impact of the device independently from the effect of the inhaled drug [51]. In one comparative analysis of adherence with seven different types of inhalers, Respimat SMI was associated with the lowest risk of underuse (5.5%), defined as taking < 50% of doses as prescribed, in patients with COPD [51]. MDIs were associated with a higher rate of overuse (taking > 125% of doses) and a lower rate of optimal use (≥ 75% and ≤ 125%) compared with Respimat SMI in this analysis [51].

Inadvertent non-adherence may be an important consideration here because patients who use their inhaler incorrectly are not receiving the optimal dose. MDIs have a high rate of errors because of the need to coordinate actuation and inhalation [52]. In addition, patients using MDIs may still think the inhaler is working when it is empty, which leads to inadvertent underdosing, but this is not possible with the Respimat SMI, which cannot release a dose from an empty device. Alternatively, patients using a Turbuhaler are often unaware of the drug being administered because there is no taste, and may administer a second one “just in case,” leading to overdosage.

4.3 Patient Preference

The practical benefits of the Respimat SMI have been borne out in several clinical studies assessing inhaler preference in patients with obstructive lung disease [53]. In one such study, the patients who expressed a preference for one inhaler over another (N = 201) significantly (p < 0.001) favored the Respimat SMI, with 81% reporting a preference for Respimat SMI compared with 19% favoring the MDI. The total score from the questionnaire was also significantly (p < 0.001) higher for Respimat SMI than for MDI, as were the mean scores for 13/15 satisfaction questions (p < 0.05) [53].

In another study, 153 patients with asthma were asked to complete a questionnaire to assess patient preferences of Respimat SMI versus DPI. The total satisfaction score was significantly (p < 0.0001) higher for Respimat SMI (85.5) than for DPI (76.9), and the majority of patients preferred Respimat SMI (74%) to DPI (17%). Additionally, the mean willingness-to-continue score for Respimat SMI (80/100) was higher than that for DPI (62/100) [44].

In a survey conducted in 57 patients with COPD to investigate the preferences for the HandiHaler and Respimat SMI, 46% of patients preferred the Respimat SMI and 18% preferred the HandiHaler [35]. In a follow-up survey conducted 2–3 years later (N = 39), the percentage of patients who preferred the Respimat SMI increased from 39 to 80% [35]. Similarly, in a randomized comparison in patients with COPD, performance domain scores and total scores in the PASAPQ were significantly higher in the group of patients who were using the Respimat SMI than in the group receiving the same combination of treatments via an MDI (p < 0.001), and patients in the Respimat SMI group were less likely to discontinue treatment (15.3%) compared with the MDI group (23.4%) [54].

The preference for Respimat in these studies is consistent with other data showing that patients with COPD prefer more modern inhalers to the Handihaler. For example, in trials comparing the low-resistance Breezhaler DPI with the high-resistance HandiHaler DPI, the Breezhaler was superior in both dose delivery and patient preference [55, 56]. However, comparisons between the Breezhaler and Respimat SMI are not as clear-cut. While there are some data to suggest that patients with COPD prefer the Breezhaler inhaler over Respimat SMI [57], other studies have found that both devices are ranked equally high by patients [58]. Comparative studies show that the rate of handling errors was low and similar with both devices [57]. The most frequent difficulty patients had with the Breezhaler was inserting the capsule into the device [57], which requires manual dexterity and fine motor skills [45].

5 Conclusions

Aerosol medication remains the cornerstone of treatment for pulmonary conditions, offering targeted drug delivery to the lungs and rapid relief of symptoms.

Respimat SMI was designed with the features of an ideal inhalation device in mind. It actively delivers an aerosol with a high fine-particle fraction at a slow velocity, which improves overall drug deposition in the lungs with less unwanted oropharyngeal deposition. Furthermore, the slower velocity and longer duration of the aerosol cloud delivered by Respimat SMI simplifies coordination of actuation and inhalation for the patient.

All inhalers have potential disadvantages and for the Respimat – these include cost and the need for priming. However, the patient-centered design features of Respimat SMI generally outweigh these disadvantages, since preference and satisfaction data show that patients find Respimat SMI easy to use and prefer it to other inhalation devices. Improved patient satisfaction may help to promote long-term adherence and improve clinical outcomes with respiratory maintenance therapy.

References

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2018. http://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed 7 June 2018.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. 2018. http://goldcopd.org/. Accessed 7 June 2018.

Stein SW, Thiel CG. The history of therapeutic aerosols: a chronological review. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2017;30(1):20–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2016.1297.

Sanders M. Inhalation therapy: an historical review. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16(2):71–81. https://doi.org/10.3132/pcrj.2007.00017.

Myrdal PB, Sheth P, Stein SW. Advances in metered dose inhaler technology: formulation development. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014;15(2):434–55. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-013-0063-x.

Wachtel H, Kattenbeck S, Dunne S, Disse B. The Respimat® development story: patient-centered innovation. Pulm Ther. 2017;3(1):19–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-017-0040-8.

Ibrahim M, Verma R, Garcia-Contreras L. Inhalation drug delivery devices: technology update. Med Dev (Auckl). 2015;8:131–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/mder.S48888.

Newman SP. Dry powder inhalers for optimal drug delivery. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4(1):23–33. https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.4.1.23.

Yawn BP, Colice GL, Hodder R. Practical aspects of inhaler use in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the primary care setting. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:495–502. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S32674.

Laube BL, Janssens HM, de Jongh FH, et al. What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1308–31. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00166410.

Makela MJ, Backer V, Hedegaard M, Larsson K. Adherence to inhaled therapies, health outcomes and costs in patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107(10):1481–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2013.04.005.

Bourbeau J, Bartlett SJ. Patient adherence in COPD. Thorax. 2008;63(9):831–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2007.086041.

Small M, Anderson P, Vickers A, Kay S, Fermer S. Importance of inhaler-device satisfaction in asthma treatment: real-world observations of physician-observed compliance and clinical/patient-reported outcomes. Adv Ther. 2011;28(3):202–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-010-0108-4.

Chrystyn H, van der Palen J, Sharma R, et al. Device errors in asthma and COPD: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27:22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0016-z.

Roggeri A, Micheletto C, Roggeri DP. Inhalation errors due to device switch in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma: critical health and economic issues. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:597–602. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S103335.

Usmani Omar S. Inhaled drug therapy for the management of asthma. Prescriber. 2015;26(3):23–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/psb.1303.

Haidl P, Heindl S, Siemon K, Bernacka M, Cloes RM. Inhalation device requirements for patients’ inhalation maneuvers. Respir Med. 2016;118:65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2016.07.013.

Bagherisadeghi G, Larhrib EH, Chrystyn H. Real life dose emission characterization using COPD patient inhalation profiles when they inhaled using a fixed dose combination (FDC) of the medium strength Symbicort® Turbuhaler®. Int J Pharm. 2017;522(1–2):137–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.02.057.

Filuk R. Delivery system selection: clinical considerations. Am Health Drug Benefit. 2008;1(Suppl 8):13–7.

Dalby RN, Eicher J, Zierenberg B. Development of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler and its clinical utility in respiratory disorders. Med Devices (Auckl). 2011;4:145–55. https://doi.org/10.2147/MDER.S7409.

Perriello EA, Sobieraj DM. The Respimat Soft Mist Inhaler, a novel inhaled drug delivery device. Conn Med. 2016;80(6):359–64.

Anderson P. Use of Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2006;1(3):251–9.

Smith G, Hiller C, Mazumder M, Bone R. Aerodynamic size distribution of cromolyn sodium at ambient and airway humidity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121(3):513–7. https://doi.org/10.1164/arrd.1980.121.3.513.

Hochrainer D, Holz H, Kreher C, Scaffidi L, Spallek M, Wachtel H. Comparison of the aerosol velocity and spray duration of Respimat Soft Mist inhaler and pressurized metered dose inhalers. J Aerosol Med. 2005;18(3):273–82. https://doi.org/10.1089/jam.2005.18.273.

Usmani OS, Biddiscombe MF, Barnes PJ. Regional lung deposition and bronchodilator response as a function of beta2-agonist particle size. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(12):1497–504. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200410-1414OC.

Iwanaga T, Kozuka T, Nakanishi J, et al. Aerosol Deposition of inhaled corticosteroids/long-acting β2-agonists in the peripheral airways of patients with asthma using functional respiratory imaging, a novel imaging technology. Pulm Ther. 2017;3(1):219–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-017-0036-4.

Pitcairn G, Reader S, Pavia D, Newman S. Deposition of corticosteroid aerosol in the human lung by Respimat Soft Mist inhaler compared to deposition by metered dose inhaler or by Turbuhaler dry powder inhaler. J Aerosol Med. 2005;18(3):264–72. https://doi.org/10.1089/jam.2005.18.264.

Newman SP, Brown J, Steed KP, Reader SJ, Kladders H. Lung deposition of fenoterol and flunisolide delivered using a novel device for inhaled medicines: comparison of RESPIMAT with conventional metered-dose inhalers with and without spacer devices. Chest. 1998;113(4):957–63.

Brand P, Hederer B, Austen G, Dewberry H, Meyer T. Higher lung deposition with Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler than HFA-MDI in COPD patients with poor technique. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3(4):763–70.

Kruger P, Ehrlein B, Zier M, Greguletz R. Inspiratory flow resistance of marketed dry powder inhalers (DPI). Eur Respir J. 2014;44(Suppl):4635.

Jarvis S, Ind PW, Shiner RJ. Inhaled therapy in elderly COPD patients; time for re-evaluation? Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):213–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl174.

Ciciliani AM, Langguth P, Wachtel H. In vitro dose comparison of Respimat® inhaler with dry powder inhalers for COPD maintenance therapy. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1565–77. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S115886.

Tamura G. Comparison of the aerosol velocity of Respimat® soft mist inhaler and seven pressurized metered dose inhalers. Allergol Int. 2015;64(4):390–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alit.2015.06.012.

Dahl R, Kaplan A. A systematic review of comparative studies of tiotropium Respimat® and tiotropium HandiHaler® in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: does inhaler choice matter? BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0291-4.

Hanada S, Wada S, Ohno T, Sawaguchi H, Muraki M, Tohda Y. Questionnaire on switching from the tiotropium HandiHaler to the Respimat inhaler in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: changes in handling and preferences immediately and several years after the switch. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:69–77. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S73521.

Molimard M, Raherison C, Lignot S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation and inhaler device handling: real-life assessment of 2935 patients. Eur Respir J. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01794-2016.

Schmiedl S, Fischer R, Ibanez L, et al. Tiotropium Respimat® vs. HandiHaler®: real-life usage and TIOSPIR trial generalizability. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(2):379–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12808.

Ichinose M, Fujimoto T, Fukuchi Y. Tiotropium 5μg via Respimat and 18μg via HandiHaler; efficacy and safety in Japanese COPD patients. Respir Med. 2010;104(2):228–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2009.11.011.

van Noord JA, Cornelissen PJ, Aumann JL, Platz J, Mueller A, Fogarty C. The efficacy of tiotropium administered via Respimat Soft Mist Inhaler or HandiHaler in COPD patients. Respir Med. 2009;103(1):22–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.10.002.

Wise RA, Anzueto A, Cotton D, et al. Tiotropium Respimat inhaler and the risk of death in COPD. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1491–501. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1303342.

Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluna JJ, Alcazar B, Viejo JL, Garcia-Rio F. Factors affecting the selection of an inhaler device for COPD and the ideal device for different patient profiles. Results of EPOCA Delphi consensus. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2017.10.006.

Davis KH, Su J, Gonzalez JM, et al. Quantifying the importance of inhaler attributes corresponding to items in the patient satisfaction and preference questionnaire in patients using Combivent Respimat. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0780-z.

Hodder R, Price D. Patient preferences for inhaler devices in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: experience with Respimat Soft Mist inhaler. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:381–90.

Hodder R, Reese PR, Slaton T. Asthma patients prefer Respimat® Soft Mist™ Inhaler to Turbuhaler®. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:225–32.

Dougall S, Bolt J, Semchuk W, Winkel T. Inhaler assessment in COPD patients: A primer for pharmacists. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2016;149(5):268–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163516660573.

Bournival R, Coutu R, Goettel N, et al. Preferences and inhalation techniques for inhaler devices used by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2018;31(4):237–47. https://doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2017.1409.

Kamin W, Frank M, Kattenbeck S, Moroni-Zentgraf P, Wachtel H, Zielen S. A handling study to assess use of the Respimat® Soft Mist Inhaler in children under 5 years old. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2015;28(5):372–81. https://doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2014.1159.

Dal Negro RW, Povero M. Acceptability and preference of three inhalation devices assessed by the Handling Questionnaire in asthma and COPD patients. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2015;11:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40248-016-0044-5.

Dal Negro RW, Povero M. The economic impact of educational training assessed by the Handling Questionnaire with three inhalation devices in asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease patients. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:171–6. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S104066.

Dima AL, Hernandez G, Cunillera O, Ferrer M, de Bruin M. Asthma inhaler adherence determinants in adults: systematic review of observational data. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(4):994–1018. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00172114.

Koehorst-ter Huurne K, Movig K, van der Valk P, van der Palen J, Brusse-Keizer M. The influence of type of inhalation device on adherence of COPD patients to inhaled medication. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13(4):469–75. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425247.2016.1130695.

Rootmensen GN, van Keimpema AR, Jansen HM, de Haan RJ. Predictors of incorrect inhalation technique in patients with asthma or COPD: a study using a validated videotaped scoring method. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23(5):323–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2009.0785.

Schurmann W, Schmidtmann S, Moroni P, Massey D, Qidan M. Respimat Soft Mist inhaler versus hydrofluoroalkane metered dose inhaler: patient preference and satisfaction. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4(1):53–61.

Ferguson GT, Ghafouri M, Dai L, Dunn LJ. COPD patient satisfaction with ipratropium bromide/albuterol delivered via Respimat: a randomized, controlled study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:139–50. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S38577.

Chapman KR, Fogarty CM, Peckitt C, et al. Delivery characteristics and patients’ handling of two single-dose dry-powder inhalers used in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:353–63. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S18529.

Colthorpe P, Voshaar T, Kieckbusch T, Cuoghi E, Jauernig J. Delivery characteristics of a low-resistance dry-powder inhaler used to deliver the long-acting muscarinic antagonist glycopyrronium. J Drug Assess. 2013;2(1):11–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/21556660.2013.766197.

Oliveira MVC, Pizzichini E, da Costa CH, et al. Evaluation of the preference, satisfaction and correct use of Breezhaler® and Respimat® inhalers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—INHALATOR study. Respir Med. 2018;144:61–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2018.10.006.

Miravitlles M, Montero-Caballero J, Richard F, et al. A cross-sectional study to assess inhalation device handling and patient satisfaction in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:407–15. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S91118.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tsuyoshi Fujimoto, now retired from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, who contributed to the early drafts of the manuscript. Medical writing assistance, funded by Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided by Frances Weir of Ashfield Healthcare Communications, part of UDG Healthcare plc, and Catherine Rees of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, who edited the manuscript before submission. Publication management was provided by Mami Mori of Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YT, SN, and YN participated in the conception of the review. YT and TI participated in the collection of data/references. All authors were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data/references; in the drafting and/or writing of the manuscript; and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Financial support for the development of this manuscript was provided by Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim.

Conflict of interest

TI received honoraria from Kyorin Pharmaceutical; received research funding from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Teijin Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma and Kyorin Pharmaceutical. YT held an advisory role for Kyorin Pharmaceutical and Meiji Seika Pharma; received honoraria from Teijin Pharma, AstraZeneca, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Torii Pharmaceutical, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis Pharma and Daiichi Sankyo; received research funding from Daiichi Sankyo, Teijin Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical and Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical. SN and YS are employees of Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Iwanaga, T., Tohda, Y., Nakamura, S. et al. The Respimat® Soft Mist Inhaler: Implications of Drug Delivery Characteristics for Patients. Clin Drug Investig 39, 1021–1030 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-019-00835-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-019-00835-z