Abstract

Introduction

A comprehensive package of immunization services is an internal component of the Essential Health Service Package (ESP) implemented by Government of Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR). Thus, the cost of delivering the immunization program and its feasibility given the fiscal space emerges as an important policy question. The present analysis was undertaken to estimate the total cost of implementing the immunization program under ESP, determinants of total cost and the program’s fiscal implications from the government’s perspective.

Methodology

We employed a normative costing approach for costing of immunization services under ESP. Standard treatment guidelines (STGs) from both within and outside Lao PDR were considered to identify the resource use for each vaccine delivery. Subsequently, cost per dose administered and fully immunized beneficiary were computed. We assessed the fiscal space for financing immunization services in Lao PDR by adapting the decomposition method given by Tandon et al.

Results

In 2019, the estimated total cost of financing immunization in Lao PDR was US$12 million, which will increase in 2025 by 1.75 times, to US$21 million. The per capita budget for immunization needs to increase from about US$2 to US$7. Introduction of newer vaccines in the immunization schedule accounts for the major share (60%) of the increased cost for financing immunization. In view of current fiscal space, the government immunization expenditure (GIE) allocations will be adequate only in a scenario where no new vaccine is introduced under ESP in future years.

Conclusion

The current fiscal space would fall short of meeting the aspirational goals of ESP–Immunization for the introduction of newer vaccines in Lao PDR. The present analysis of the fiscal space provides important evidence to support a greater role for the Global Alliance for Vaccine Initiative (GAVI) to continue to finance immunization in Lao PDR. A publicly financed immunization model in Lao PDR would require significant strategic amendments with low short-term viability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The per capita cost of immunization needs to increase from about US$2 to US$7 for financing immunization services in Lao PDR. Introduction of newer vaccines to the immunization schedule accounts for the major share (60%) of the increased cost for financing immunization. |

In view of the current fiscal space, the government immunization expenditure (GIE) allocations will be adequate only in a scenario where no new vaccine is introduced under the Essential Health Service Package (ESP) in future years. |

The Government of Lao PDR needs to study the current and future fiscal space to meeting the aspirational goals of ESP–Immunization for introduction of newer vaccines in the country. |

1 Introduction

In the last decade, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have witnessed major health system reforms. As a part of these reforms, a major focus had been to increase public investment and prioritize healthcare interventions which reflect better value for investments [1,2,3]. Preventive services such as vaccinations have evident health and economic benefits [4,5,6,7,8]. An analysis done for low-income countries revealed that $1 invested in immunization can potentially save $16 in account of healthcare costs and productivity losses [4].

In Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR), the National Immunization Program (NIP) is well established. Funding of immunization services is the collective responsibility of government, however external funding of immunization services has been the backbone of the health system in Lao PDR, which has been actively increasing its contribution.

The Global Alliance for Vaccine Initiative (GAVI) has supported the country since 2002, providing cash support, support for newer vaccine introductions, immunization services support and health system strengthening (HSS) grants, among others [9]. Overall, the contribution of Government and GAVI towards financing immunization in Lao PDR is 55% and 11%, respectively [10]. GAVI’s latest funding grant to Lao PDR is expected to end by 2023 and the government is expected to develop a new strategy to self-finance and procure resources for immunization. Other sources include external donors, development partners, the private sector and the community [10].

Recently, the Government proposed a comprehensive Essential Health Service Package (ESP) to be implemented from 2018 to 2023. A comprehensive package of immunization services is an integral component of ESP. Although the ESP for immunization has been finalized by identifying basic services from relevant national strategies and action plans, the cost of delivering the immunization program and its feasibility given the fiscal space is an important policy question. Hence, we undertook the present analysis to estimate the total cost of implementing the immunization program as part of the ESP, determinants of the total cost and its fiscal implications from the Lao PDR Government’s perspective.

2 Methodology

2.1 Essential Health Service Package (ESP) and Immunization in Lao PDR

Lao PDR has been on the path of robust economic growth in the past decades. The per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of the country is US$2457 in 2017. With an annual growth rate of 4.9% in GDP, the country is performing on par with other rapidly developing economies. The public expenditure or general government expenditure (GGE) as a percentage of GDP has seen a rising trend over the last ~ 15 years. Government Health Expenditure (GHE) as a percentage of GDP has increased from 0.4 to 1.3% during the last 20 years [11]. Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the growth trends of macroeconomic indicators and Lao PDR is no different [12]. An early evidence report depicted that the COVID-19 pandemic in Lao PDR impacted essential healthcare service delivery, with maternal and immunization services being worst affected [13]. The ESP package comprises essential preventive, promotive, diagnostic, screening, curative, palliative and rehabilitation health services. The immunization service package is one essential component under ESP. The roadmap under ESP–Immunization ensures increase in coverage and sustainability of traditional vaccines alongside rollouts of newer vaccines. The newer vaccines include rotaviral enteritis, human papillomaviruses (HPV), pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) 3, inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) and typhoid etc. As per the present service delivery patterns, more than 60% of the demand for immunization is met through outreach services [10].

2.2 Costing Approach

Various approaches towards costing of health care services have been described in literature [14,15,16,17]. Traditional micro-costing methods such as top-down or bottom-up costing are dependent on actual use of resources to provide services and are thus subject to bias if the infrastructure is underfunded, or service delivery is inefficient, or not appropriately organized, or if the quality of care is compromised. Hence, a normative costing approach is preferred over other approaches to estimate the cost of scaling up existing services, or for estimating the cost of an essential service package in a supply-side financing mode [17]. We employed a normative costing approach for costing of immunization services under ESP. The normative costing approach assumes standard resource use for service delivery as per norms of standard treatment guidelines (STGs) or experts’ judgement in the absence of STGs.

2.3 Data Collection and Sources

There were several steps involved in data collection for normative costing of the ESP–Immunization. First was the identification of immunization services by level of service delivery, which involved categorization of vaccines by mode of service delivery (i.e., outreach and health facilities). A Technical Working Group (TWG) was constituted with a medical doctor, a program manager, health worker, public health professional, representative of development partners and officials from the Ministry of Health. The TWG provided information pertaining to the current pattern of immunization service delivery and the proposed micro plans for the future. In this process, TWG referred to standard treatment guidelines (STGs) from both within and outside Lao PDR to identify the resource use for each vaccine delivery. These resources included clinical human resources, vaccines and consumables for each dose/injection administered at different levels of service delivery. In addition, they also identified the quantity of each resource required per dose/injection administered. Second, data on prices of each of these resources were obtained from a list of procurement prices in the public health system in Lao PDR [18]. Third, volume of services for each vaccine was computed based on eligible population, coverage, and mode of service delivery (i.e., fixed, outreach and mobile). Finally, data on the expenditure of program management including training, communication, travel, supervision etc. were obtained from the immunization program division in Lao PDR. Vaccine delivery (including capital cold chain operation costs), capital investment in cold chain capacity and other shared health system costs such as buildings were excluded. After expert consultations, it was realized that no augmentation in capital infrastructure would be needed in the next 5 years for vaccine delivery. Details about key assumptions and data used for normative estimation are presented in supplementary table 1 (see electronic supplementary material [ESM].

2.4 Cost Analysis

The endpoints of cost analysis were the estimates for annual recurrent cost of immunization, annual cost by vaccine type, type of input resources, share of government and donors, distribution between facility versus outreach and traditional versus newer vaccines. Finally, cost per dose administered and fully immunized beneficiary were computed. We also estimated the costs for varying combinations of delivery strategies—fixed, outreach or mobile. Two different scenarios were compared in terms of cost: scenario 1—current levels of coverage using current delivery patterns, and scenario 2—achieving the target level of coverage (i.e., 95%) using the current delivery pattern; we report year-wise estimates from 2019 to 2025. All the estimates are reported in US dollars (US$) using an exchange rate of 8762.57 Lao Kip per US$1 in 2019 [11]. More details about cost data analysis are provided in supplementary section S2 (see ESM).

2.6 Fiscal Space Analysis

In classical terms, ‘fiscal space’ for health is defined as scope in government’s resource pool to allocate additional resources for health without risking sustainability of its financial situation [19,20,21]. We assessed the fiscal space for financing immunization services in Lao PDR by adapting the approach by Tandon et al. [22]. Tandon et al. assess the fiscal space for health using a decomposition method based on three factors: (i) conducive macroeconomic conditions, (ii) reprioritization of health within the government budget and (iii) an increase in health sector-specific resources (i.e., earmarked funds). The decomposition method based on these factors uses the variables share (%) of health in public expenditure, public expenditure as a share (%) of GDP and GDP of the country to predict the per capita government expenditure for health. As our analysis focussed only on the immunization component of health, an additional variable—share (%) of immunization expenditure in total government health expenditure—was used to adapt the decomposition equation. The modified decomposition equation is given in Box 1. Equation 3 in Box 1 shows that the income elasticity of per capita public financing for immunization is determined by the additive relationship of income elasticity of share of immunization expenditure in public health expenditure, share of public health expenditure in total government expenditure and total government expenditure in GDP.

The data pertaining to health share in public expenditure, public expenditure as a share (%) of GDP and Lao PDR per capita GDP were accessed from WHO’s Global Health Expenditure Database [23], while the data on immunization expenditure were accessed from WHO and UNICEF’s Joint Reporting Process website [23]. Lastly, the yearly official exchange rates of Lao Kip per US$ were taken from the World Bank Database [11].

2.7 Decomposition Analysis for Fiscal Space

Using the decomposition equation (Box 1), we forecasted the government immunization expenditure (GIE) for Lao PDR from 2020 to 2025. We present both pooled and independent effects of predictive factors on GIE forecasted from 2020 to 2025. In the base-case analysis, the forecasted GIE from 2020 to 2025 is influenced by trends in the predicting factors in the equation (Box 1). A sensitivity analysis was also undertaken to assess the exclusive effect of these factors in increasing (or decreasing) the GIE in the future years. Each of these factors were varied individually in the decomposition equation, keeping others constant. We also performed a scenario analysis assuming the Government considers reprioritization of public financing for health as a percentage of general government expenditure (GGE) at varying scales and its impact on GIE [22]. In 2019, the share of GHE in GGE was 4%. In view of the global average share of GHE (i.e., 11%), we considered increasing it to a maximum of 8% in the current scenario analysis. Lastly, we considered a scenario involving reduction in vaccine costs in future years and its impact on overall estimated cost of the immunization program in Lao PDR.

3 Results

3.1 ESP–Immunization Costs

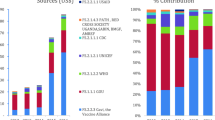

In 2019, the estimated total cost of financing immunization in Lao PDR was US$12 million, which is expected to increase by 1.75 times in 2025 to US$21 million (Fig. 1A). For the same period, the per capita cost of immunization needs to be increased from US$2 to US$7. The gradient for the increase in cost of child immunization alone is 3-fold. The estimated total cost is US$2.2 million in 2019 and US$6.6 million in the year 2025. Similarly, the cost per infant child varied from US$1.8 in the year 2019 to US$4.7 in the year 2025 (Fig. 1B). Introduction of newer vaccines to the immunization schedule accounts for a major share (> 60%) of the increased cost for financing immunization (Fig. 1C).

Overall and breakdown of resource requirements for funding immunization as per the Essential Service Package (In US$), 2019–2025. US$ United States dollars. A Total resource requirement for immunization 2019–2025 (inclusive of costs of service delivery and scale up for program management, governance and administration expenses). B Resource requirement for infant immunization with cost per infant child plotted on secondary axis. C Total cost of the immunization program when implemented with traditional vaccines (tetanus diphtheria adult vaccine to childbearing age women, tetanus toxoid in antenatal care, hepatitis B at birth, BCG, MR, DPT-Hep3- Hib3 coverage, JE, Polio OPV); with additional cost if newer vaccines (PCV3, polio IPV, rotavirus, human papilloma virus, typhoid) are added to traditional ESP. Year-wise program management, governance, administration costs are included in each year. D Total resource requirements for ESP implementation with traditional vaccines by type of input resource, i.e., human resource, vaccines and consumables. Year-wise program management, governance, and administration costs are excluded

In terms of input resources, the vaccine cost comprises 78.7% of the total cost of ESP–Immunization, followed by human resources (17%) and consumables (4%). The share of vaccine costs is estimated to increase further in 2025 to 81% as a result of the introduction of newer vaccines in subsequent years (Fig. 1D). The HPV vaccine has the highest share (30%), followed by PCV 3 (18%), tetanus-diphtheria (Td) to childbearing age women (CBAW; 13%) and rotavirus vaccine (8.5%).

In the baseline year (2019), fixed-site immunization delivery comprises one-fourth of the total cost, while immunization through outreach and mobile delivery modes constitutes three-fourths of the total cost. If the coverage is increased to 95% by 2025 with similar delivery patterns, the total cost increases from US$12 million to US$16 million (Fig. 2).

3.2 Fiscal Implications

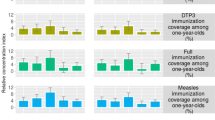

As per the currently available fiscal space, the GIE allocations will be adequate only in a scenario where no new vaccine is introduced under ESP in future years, and only traditional vaccines are provided (Fig. 3). None of these factors (i.e., macroeconomic growth, ability to raise public expenditures, prioritization of health within the Government spending and prioritization of immunization within health budgets) on their own can drive GIE growth to the same level in future years (Fig. 4). Positive macroeconomic growth does have a boosting impact on GIE, but a significant (60–80%) shortfall persists to meet ESP requirements. The findings from the scenario analyses suggest that, if the share of GHE in GGE increases by 60% relatively, the projected GIE will be adequate to meet the ESP requirement by 2024, while if the GHE share is doubled, the ESP requirement can be met in 2023 (Fig. 5).

Estimations of government immunization expenditure (2020–2025) decomposing factors independently in decomposition equation, Lao PDR. Method A (GIE projections): Tandon A et al.; World Bank, 2018. Scenarios: (1) GDP growth only: Only natural growth of GDP is considered and GHE, GGE and GIE are kept constant using method A. (2) GGE growth only: Only natural growth of GGE is considered and GHE, GDP and GIE are kept constant using method A. (3) GHE growth only: Only natural growth of GHE is considered and GDP, GGE and GIE are kept constant using method A. GDP gross domestic product, GHE government health expenditure, GIE government immunization expenditure

Lastly, if the vaccine prices can be reduced by 15% or more from their current prices, the ESP requirements and GIE projected estimate curves will coincide in the year 2025. This implies projected GIE will be adequate to meet the ESP requirements given a 15% or more reduction in vaccine prices in future years (Fig. 6).

4 Discussion

In 2019, the estimated total cost of financing comprehensive immunization in Lao PDR was US$12 million, increasing by 1.75 times to US$21 million by 2025 (Fig. 1). In per capita terms, a rise from US$2 to US$7 is needed from 2019 to 2025. Introduction of newer vaccines to the immunization schedule accounts for the major share of the increased cost for financing immunization. A large share of the total ESP–Immunization cost is determined by the cost of vaccines (approx. 80%).

A recent analysis for 94 LMICs estimated the cost of delivering ten key vaccines under a routine immunization program for two decades (2011–2030) to be US$70.8 billion or US$35.8 per surviving infant. If considered only for the period from 2011 to 2020, the estimated cost was US$28.8 billion, which translates to an average allocation of 0.4% of GDP for the immunization program [24]. In 2019, the total immunization expenditure (TIE) of Lao PDR (0.059% of GDP) was more than other LMICs such as India (0.010%), Cambodia (0.039%) and Bangladesh (0.033%). In terms of the government’s share of TIE, Lao PDR with 36% was better than Cambodia (29%) and Nepal (23%), but worse than India (100%) and Cambodia (39%).

The present scale-up analysis shows that there will be a shortfall in immunization financing goals set by ESP. The GIE projections will only be adequate in a scenario where no new vaccine is introduced under ESP in future years, or in other words, the immunization program is continued with traditional vaccines only (Fig. 3). The ESP financing requirements can be met by government funding by 2025, in a scenario where the GDP of the country increases by 1.7 times in the next 5 years or the proportion of GHE in GGE is doubled (Fig. 4). The GDP factor is not controllable, nor it is realistic to achieve such a high growth even with significant economic reforms. However, the latter can be achieved with better political commitment to health. Some recent analyses from LMICs also highlighted the need for increasing the resource allocation for health [25].

In the context of immunization, the GHE on immunization as a proportion of overall GHE in Lao PDR showed an increase from 2006 to 2017 [26]. The GAVI immunization expenditure broadly remained unchanged in the same period. On the contrary, there was a decline in immunization expenditure by donor agencies other than GAVI in the period from 2006 to 2017 [26]. In 2017, around 60% of the immunization expenditures were met through public funding, while GAVI and other donors contributed 40%. GAVI provided a specific share of 23% of the TIE [10, 26].

Whilst there was a sharp increase in the per-infant GIE in Lao PDR from US$1.4 in 2012 to US$44.1 in 2019 [26], the current growth rate of GIE was found to be grossly inadequate to meet the goals set by ESP (Fig. 3). Publicly financed implementation of ESP–Immunization does not seem to be feasible in Lao PDR, given the current state of immunization financing. Several strategic amendments targeting the factors which influence immunization financing could make publicly financed implementation of ESP–Immunization feasible in Lao PDR. First, the current growth rate in GIE would be adequate for ESP–Immunization if the introduction of newer vaccines is dropped from the plan. However, this is not considered viable in view of the demand for these vaccines. Second, if reprioritization of GHE is considered, projected GIE would be enough to meet ESP requirements. In 2019, the GHE was 4% of GGE and, in view of a global average of 11%, we considered increasing GHE from 4 to 8% in future years. In a scenario whereby there was a 60% increase in GHE as percentage of GGE, the GIE will be sufficient to meet the ESP requirements by 2024, while ESP requirements could be met in 2023 if GHE is doubled to 8% (Fig. 5). Lastly, if the current vaccine prices can be reduced by 15% or more with strategic purchasing, the immunization services in Lao PDR could become completely publicly financed by 2025. The latter is the most viable scenario as the vaccine costs drive the total cost of ESP–Immunization, accounting for more than 80% of costs.

In Lao PDR, before 2012, the donor agencies UNICEF and WHO played a key role in immunization financing, later transitioning to the government and GAVI taking over the greater share of immunization financing. As per the terms of coaction, GAVI is committed to supporting the immunization program in Lao PDR until 2023; nevertheless, the extension of support is under consideration. The Government of Lao PDR is expected to make necessary strategic amendments to self-finance the immunization program in the absence of GAVI, which appears less plausible with the current growth trajectory of GIE [27, 28]. Other LMICs like Lao PDR are also not in a state to sustain a comprehensive immunization program in the absence of co-financing [27,28,29]. The need for integrating financial sustainability planning for immunization as a part of national budget planning has also been highlighted [27, 30].

The health system issues related to financing and delivery have been further intensified due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As per a recent estimate, the disruptions caused by COVID-19 in essential healthcare delivery could potentially result in 25% and 31% additional child and maternal deaths by 2021. More specifically, the coverage for oral antibiotics for pneumonia in children could reduce from 39 to 19%, while the coverage of the DPT (diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus) vaccine could fall from 68 to 33%, translating to additional child mortality [31]. The Lao PDR’s health system is already underfunded with two-thirds being financed out-of-pocket and through external funders [32]. There is an urgent need to build a resilient health system with service delivery and financing mechanisms [13].

The results of this analysis need to be viewed keeping a few limitations in mind. First, the cost analysis of immunization services was conducted from a financial perspective and includes salaries, vaccines, consumables, and program management costs. No increase in capital costs regarding implementation of the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) have been considered. Consultation with experts suggested that no augmentation in capital infrastructure would be needed in the next 5 years pertaining to vaccine delivery. However, these costs are not expected to bring major changes to the results unless significant reforms in infrastructure are undertaken by Government agencies for service delivery of immunization services in Laos. Second, we assumed a linear scale up for several vaccines over the reference years, so the costs also increase. In the absence of any published evidence on the patterns of increase in immunization service utilization during the initial years following EPI implementation, this was considered the best approach to follow. Moreover, input resources that have been valued are unlikely to have a non-linear cost function. Adapting the immunization services as a package to actual service utilization at the client level was a challenge wherein many services had to be segregated into components to accurately estimate costs. This was done using the latest program guidelines, which is the standard approach in these scenarios. The time spent by human resources for service provision was not elicited through a time motion study but determined using the expert group opinion which is again a well-established approach for costing. We did not estimate costs for quality improvement measures. Third, the costs of monitoring and supervision; information education and communication (IEC) and social mobilization; meetings; and training in the immunization program were not estimated normatively. In fact, costs were based on actual budgets, as no major changes were foreseen in the patterns of program monitoring and management by program experts. This may lead to underestimation of these costs; however, it will not affect the overall results significantly. This is because these costs comprise only a small proportion of total estimated costs; and these costs increase proportionate to any increase in estimated budget. Fourth, the fiscal analysis would have benefited from comprehensively evaluating the fiscal space (and fiscal deficit too) [33], which implies simulating the potential scenarios of availability of public resources, the state of tax revenues, improved efficiency, prioritization within the service package and other associated factors in the context of Lao PDR. This is beyond the scope of the present analysis for two reasons: granular data is currently not available for all potential factors to extend the fiscal analysis and the decomposition equation allows inclusion of limited variables. Lastly, the scope for improvement in efficiency of healthcare spending is a critical determinant of fiscal space for health. Assessment of efficiency typically requires a cost-effectiveness analysis to estimate the costs and outcomes associated with use of different strategies. This is beyond the scope of present analysis as only cost evaluation was done for the proposed ESP immunization. We recommend a comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis to fill the evidence gaps by incorporating the role of efficiency in prioritization of resources and enhancing fiscal space for health in general, and immunization in particular.

5 Conclusion and Recommendations

The routine immunization program in Lao PDR covers the usual traditional vaccines as part of the EPI program. In addition, the ESP aspires to cover several new vaccines to children and the adolescent population. The financing for immunization is shared almost equally between government spending, GAVI and other donors as well. However, GAVI plans to phase out from Lao PDR, beginning from 2021.

The present comparison of fiscal space with ESP requirements for financing immunization shows that, given the current trends in macroeconomic growth, ability to raise public expenditure, prioritization of health within the government spending, and prioritization of immunization within health budgets, the government financing of immunization would fall short of meeting the aspirational goals of ESP for the introduction of newer vaccines. Moreover, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has posed new and much more formidable challenges. While on one hand it has slowed the macroeconomic growth, which the present analysis shows as the single most important factor for ensuring adequate fiscal space, it has also introduced the need to immunize the population against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

As a result, the present analysis for fiscal space provides important evidence to support a greater role for GAVI to continue to finance immunization in Lao PDR. Phasing out of the GAVI from Lao PDR would significantly impact the introduction of the newer vaccines, as well as impede the mitigation of the COVID-19 impact. A publicly financed immunization model in Lao PDR would require significant strategic amendments with low short-term viability.

References

Jimenez-Soto E, Alderman K, Hipgrave D, Firth S, Anderson I. Prioritization of investments in reproductive, women’s and children’s health: evidence-based recommendations for low and middle income countries in Asia and the Pacific—a subnational focus. Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health (PMNCH) WHO. 2012.

Kaur G, Prinja S, Lakshmi P, Downey L, Sharma D, Teerawattananon Y. Criteria used for priority-setting for public health resource allocation in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2019;35(6):474–83.

Leech AA, Kim DD, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. Are low and middle-income countries prioritising high-value healthcare interventions? BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(2).

Ozawa S, Clark S, Portnoy A, Grewal S, Brenzel L, Walker DG. Return on investment from childhood immunization in low-and middle-income countries, 2011–20. Health Aff. 2016;35(2):199–207.

Ozawa S, Mirelman A, Stack ML, Walker DG, Levine OS. Cost-effectiveness and economic benefits of vaccines in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;31(1):96–108.

Batt K, Fox-Rushby JA, Castillo-Riquelme M. The costs, effects and cost-effectiveness of strategies to increase coverage of routine immunizations in low-and middle-income countries: systematic review of the grey literature. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:689–96.

Bundy DA, de Silva N, Horton S, Patton GC, Schultz L, Jamison DT, et al. Investment in child and adolescent health and development: key messages from Disease Control Priorities. Lancet. 2018;391(10121):687–99.

Munk C, Portnoy A, Suharlim C, Clarke-Deelder E, Brenzel L, Resch SC, et al. Systematic review of the costs and effectiveness of interventions to increase infant vaccination coverage in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):741.

Government of Laos. WHO. UNICEF. GAVI. Micro-Planning guide for Health Centres-Immunisation and integrated service delivery (English Version). Vientienne, Laos: Government of Laos; 2019.

Lao PDR National Immunization Programme: Updated Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2019-2025. Prelinary Draft. October 2018. 2018.

The World Bank. World Bank Open Data. Databank. https://databank.worldbank.org/home.aspx. Accessed 30 Nov 2020.

Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, Stegmuller A, Jackson BD, Tam Y, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the coronavirus pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-and middle-income countries. SSRN 3576549. 2020.

Bank W. Lao PDR Economic Monitor. MonitorLao PDR in the time of COVID-19. Thematic section: Building a resilient health system Macroeconomics, Trade and InvestmentEast Asia and Pacific Region. World Bank Group. June 2020.

Chapko MK, Liu CF, Perkins M, Li YF, Fortney JC, Maciejewski ML. Equivalence of two healthcare costing methods: bottom-up and top-down. Health Econ. 2009;18(10):1188–201.

Cunnama L, Sinanovic E, Ramma L, Foster N, Berrie L, Stevens W, et al. Using top-down and bottom-up costing approaches in LMICs: the case for using both to assess the incremental costs of new technologies at scale. Health Econ. 2016;25:53–66.

Olsson TM. Comparing top-down and bottom-up costing approaches for economic evaluation within social welfare. Eur J Health Econ. 2011;12(5):445–53.

Özaltın A, Cashin C. Costing of health services for provider payment. A practical manual based on country costing challenges, trade-offs, and solutions Arlington: Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage. 2014.

UNICEF Supply Division. UNICEF vaccine price data. 2018. Vaccines pricing data|UNICEF Supply Division. https://www.unicef.org/supply/pricing-data. Accessed 30 Nov 2020.

Barroy H, Sparkes S, Dale E, Mathonnat J. Can low-and middle-income countries increase domestic fiscal space for health: a mixed-methods approach to assess possible sources of expansion. Health Syst Reform. 2018;4(3):214–26.

Heller P. Back to basics fiscal space: what it is and how to get it. Financ Dev. 2005;42(002):3.

WHO. UHC Technical brief: strengthening health information systems. World Health Organization. 2017.

Tandon A, Cain J, Kurowski C, Postolovska I. Intertemporal dynamics of public financing for universal health coverage: accounting for fiscal space across countries: World Bank; 2018.

WHO. Global Health Expenditure Database. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/nha/database. Accessed 22 Nov 2020.

Sim SY, Watts E, Constenla D, Huang S, Brenzel L, Patenaude BN. Costs of immunization programs for 10 vaccines in 94 low-and middle-income countries from 2011 to 2030. Value Health. 2021;24(1):70–7.

Chatterjee S, Pant M, Haldar P, Aggarwal MK, Laxminarayan R. Current costs & projected financial needs of India’s Universal Immunization Programme. Indian J Med Res. 2016;143(6):801.

WHO. WHO/UNICEF joint reporting process. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/routine/reporting/en/. Accessed 25 Nov 2020.

Kamara L, Milstien JB, Patyna M, Lydon P, Levin A, Brenzel L. Strategies for financial sustainability of immunization programs: a review of the strategies from 50 national immunization program financial sustainability plans. Vaccine. 2008;26(51):6717–26.

Saxenian H, Cornejo S, Thorien K, Hecht R, Schwalbe N. An analysis of how the GAVI alliance and low-and middle-income countries can share costs of new vaccines. Health Aff. 2011;30(6):1122–33.

Cantelmo CB, Takeuchi M, Stenberg K, Veasnakiry L, Eang RC, Mai M, et al. Estimating health plan costs with the OneHealth tool, Cambodia. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(7):462.

Soeung SC, Grundy J, Maynard J, Brooks A, Boreland M, Sarak D, et al. Financial sustainability planning for immunization services in Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(4):302–9.

Preserve Essential Health Services During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Laos. Global Financing Facility. https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/country-briefs-preserve-essential-health-services-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

Alkenbrack S, Jacobs B, Lindelow M. Achieving universal health coverage through voluntary insurance. 2013.

Mathonnat J, Audibert M, Belem S. Analyzing the financial sustainability of user fee removal policies: a rapid first assessment methodology with a practical application for Burkina Faso. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(6):767–80.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support received from the Ministry of Health, Lao PDR for providing data, organizing the technical working groups and overall oversight for the study. We would also like to acknowledge the support received from World Health Organization, Swiss Red Cross, UNICEF, CHAI, ILO and the members of the ESP Costing technical advisory committee for their useful feedback in the study design and presentation of findings. Support from the WHO and CHAI for data collection is also gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SP and PB contributed to the study conception and design. Project administration was done by SP. Material preparation was performed by PB, EM, GJ and SP. Analysis was performed by PB, GJ and SP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PB, and all authors reviewed and edited the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding support

The study was supported by funding from World Bank and United Nations Population Fund.

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication (from patients/participants)

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data used for this analysis is available through open sources. The primary data on cost of immunization services in Laos can be requested from the corresponding author and will be made available subject to approval from the Ministry of Health, Lao People's Democratic Republic, as well as the World Bank office, Laos.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bahuguna, P., Masaki, E., Jeet, G. et al. Financing Comprehensive Immunization Services in Lao PDR: A Fiscal Space Analysis From a Public Policy Perspective. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 21, 131–140 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00763-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00763-8