Abstract

Background

As performance-based financing (PBF) is increasingly implemented across sub-Saharan Africa, some authors have suggested that it could be a ‘stepping stone’ for health-system strengthening and broad health-financing reforms. However, so far, few studies have looked at whether and how PBF is aligned to and integrated with national health-financing strategies, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Objective

This study attempts to address the existing research gap by exploring the role of PBF with reference to: (1) user fees/exemption policies and (2) basic packages of health services and benefit packages in the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria.

Methods

The comparative case study is based on document review, key informant interviews and focus-group discussions with stakeholders at national and subnational levels.

Results

The findings highlight different experiences in terms of PBF’s integration. Although (formal or informal) fee exemption or reduction practices exist in all settings, their implementation is not uniform and they are often introduced by external programmes, including PBF, in an uncoordinated and vertical fashion. Additionally, the degree to which PBF indicators lists are aligned to the national basic packages of health services varies across cases, and is influenced by factors such as funders’ priorities and budgetary concerns.

Conclusions

Overall, we find that where national leadership is stronger, PBF is better integrated and more in line with the health-financing regulations and, during phases of acute crisis, can provide structure and organisation to the system. Where governmental stewardship is weaker, PBF may result in another parallel programme, potentially increasing fragmentation in health financing and inequalities between areas supported by different donors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Performance-based financing (PBF) is influential in shaping the de facto package of care offered in fragile and conflict-affected settings (FCAS), including through its influence on fee-exemption or fee-reduction policies. |

PBF can be a factor for either coherence or fragmentation, depending on the context and the existing leadership and stewardship of national actors. |

Policy-makers should use PBF to support an integrated national primary-care package, with agreed financial access policies, rather than selective indicators and exemptions, varying by donors’ preferences, budget available, time period and geographical area. |

1 Introduction

Performance-based financing (PBF) schemes have been increasingly implemented in sub-Saharan Africa to improve coverage in health services and trigger positive systemic effects, by clarifying roles and responsibilities and improving transparency and accountability [1]. Under the PBF model described by Fritsche et al. [2], PBF entails a payment to healthcare providers based on their performance, measured by the quantity of services provided (based on a list of pre-identified indicators) and often adjusted by a measure of structural quality. The cash payment (or performance bonus) is normally used to cover facility running costs as well as individual staff incentives in a fixed proportion. This is typically combined with facility autonomy in deciding their use, based on a business plan. PBF schemes often include verification procedures to check the accuracy of the providers’ reports in terms of quantity, structural quality and community or client perceptions (community verification).

As PBF gained popularity, an increasing number of impact evaluations have been conducted with mixed results [3, 4], and the debate on its relevance and effectiveness continues [5]. From a theoretical perspective, some authors have called for broader conceptualisation of PBF as a ‘stepping stone’ for health-system strengthening and health-financing reforms [6]. In this context, it is important to gain a better understanding of the degree of alignment of PBF to national policies and of how PBF integrates with (and potentially strengthens) health-financing policies at country level, or contributes to further fragmentation. However, so far little literature has focused empirically on the issue of the integration of PBF with the health-financing architecture, meaning its policies and institutional set-up, in particular in fragile and conflict-affected settings (FCAS) where coordination is a challenge, and where a major evidence gap remains.

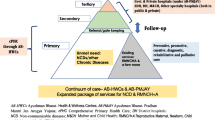

To address this gap, this study provides a comparison across three settings (Box 1) to explore the role of PBF within health-financing policies at country level. In particular, we focus on two key elements of health financing, which tend to be in place in most FCAS: (1) the user-fee reduction or exemption policies, which reflect the broader focus on equity in access to and financing of healthcare, and (2) the existing basic packages of health services (BPHS) and benefit packages, which define the services that health providers should make available to communities and patients and at what price. Although health-financing strategies aimed at Universal Health Coverage (UHC) are much broader than this focus, the definition of a health-benefit package and the reduction of out-of-pocket expenditure through user fee exemption or reduction policies for these services are cornerstones of any move towards UHC.

This work is part of a larger body of research exploring PBF in conflict-affected and humanitarian settings. A literature review of health financing in fragile settings [7] noted the growing literature on the topic of PBF and contracting approaches in such contexts and discussed some hypotheses for their proliferation in these environments. This topic was deepened by a more recent review [8], which tested these and more hypotheses and called for empirical study in a number of areas, including examining the adaptation of PBF to humanitarian settings. A comparative case study of PBF in three humanitarian settings highlighted the pragmatic adaptations that had been necessary for the model to be deployed in these challenging settings [9]. Another study examined in closer detail how PBF impacts on healthcare purchasing functions in three fragile case studies, and found PBF to remain an ‘add-on’ payment method, which had achieved some benefits but had not systematically transformed purchasing, as some early literature had hoped [10]. Given the high and increasing number of people in need of humanitarian support, estimated at 125 million people globally [11], there is a growing interest in effective financing mechanisms to ensure access to healthcare services for conflict-affected populations [12]. In line with this, improving the evidence available on the integration between PBF and health financing in humanitarian and conflict-affected settings is particularly relevant.

2 Methods

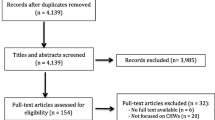

The study design adopted for this research is a comparison of multiple, embedded case studies [15]. The advantage of such a design is that case studies allow for an exploration of a phenomenon in its context, particularly when, as in this case, the context is an integral part of what is being studied, and the comparison strengthens explanatory power and analytic generalisability [16].

2.1 Data Collection

This study is based on two main sources of data: (1) secondary data collected through a review of relevant documents, and (2) primary data collected through key informant interviews (KIIs) and focus-groups discussions (FGDs) in the three study settings. We reanalysed the sources that were used for a prior linked study, for which a standard topic guide was developed so that data would be comparable across the cases. The topic guide is provided as a supplementary file to that publication [9]. In the process of data collection, a more inductive approach was followed, whereby the topic guide was tailored to each group, respondent and setting to allow for contextually relevant questions, following up on themes that came out of previous interviews and the emergence of unexpected findings. Triangulation between these different sources allowed for cross-validation, contextualisation and capturing different dimensions of the data.

The document search was carried out between June and November 2017 and focused on published and unpublished documents in each setting, including health (financing) policies and strategies, and basic packages of health services, as well as documents on the design and implementation of PBF (e.g., PBF implementation manuals, list of indicators, evaluations and annual reviews). Documents were retrieved through the database put together for this research [8, 9] and through key informants and direct knowledge of the context. In total, 25 documents were reviewed for South Kivu, 24 for Nigeria and 16 for CAR.

A mix of KIIs and FGDs were carried out between June and November 2017. FGDs and KIIs were carried out in person in Nigeria (JT, NA), remotely via phone, Skype or WhatsApp for DRC (MPB), and a mix of phone interviews and in-person KIIs and FGDs in CAR (EJ). Participants were identified through the document review, by contacting the implementing/purchasing agency and/or the MoH in each study setting, and using a snowball technique by asking interviewees to suggest others. Participants’ selection was purposeful and aimed at being as comprehensive as possible, although not all levels of the health system are included in all settings. Since the KIIs and FGDs mainly served to check policy and programmatic details, recall bias was a risk in some cases. Therefore, depending on the questions we felt different respondents could answer and the opportunities that we encountered, a choice was made between an individual KII or a FGD. The choice to conduct a FGD was in some cases also made to take advantage of existing opportunities, such as meetings that were already organised that gathered relevant stakeholders. In total, 34 KIIs and 18 FGDs among stakeholders at various levels of the health system were carried out, as shown in Table 1. The KII and FGD data were mainly used to triangulate information from the document review and did not focus on eliciting the perceptions, individual opinions or experiences from the respondents.

2.2 Data Analysis

KIIs were recorded and/or detailed notes were taken during interviews and FGDs. Interviews and FGDs lasted between 45 and 120 min. Data analysis was carried out deductively based on a framework approach [17] by manually coding and extracting information from documents and detailed interview notes based on a list of predefined, descriptive themes (provided as supplementary material), approved by all authors, which focused on (1) PBF features (history, design, institutional arrangements); (2) PBF and user fee exemption/equity mechanisms (health-financing regulatory framework, equity bonus, effectiveness of implementation, degree of integration of health-financing policies); (3) PBF, BPHS and benefit packages (national BPHS, official benefit packages, list of services included in PBF at different levels, the role of PBF in the de facto implementation of BPHS). A three-country matrix was created with input from all authors to summarise the information and to compare and contrast findings across the settings, identifying emerging patterns and differences, which are described in Sect. 3 below.

In terms of positionality, all authors have (at different levels in each country) in-depth knowledge of a network of contacts and perceived legitimacy in the respective settings where they collected data, based on previous work. However, we remain ‘outsiders’, as in ‘not local’ to those contexts. Our ‘mixed’ positionality brings advantages in terms of retaining autonomy vis-à-vis decision-makers [18] and yet being close enough to access documentation and key informants [19]. On the other hand, in our analysis we remained aware and reflective of the geographical distance and the exploratory and short-term nature of this specific study. For example, we are cognisant of the externally defined nature of the research questions we set out to explore and our deductive approach to the interpretation of the findings.

3 Findings

Detailed information about PBF’s adoption, design and implementation in the three study settings is provided in an earlier paper [9]. We focus here on the key PBF features in relation to the specific research question, looking at the integration of PBF within the health system, in particular in relation to user-fee exemptions and BPHS. Box 2 provides background on the PBF programmes in each setting.

3.1 User-Fee Exemption Mechanisms and Performance-Based Financing (PBF)

Formally committed to the goal of UHC, DRC, CAR and Nigeria have all in general terms proclaimed the need to strengthen access to healthcare through increased financial risk protection in their national health plans [20,21,22]. However, in terms of health financing and equity mechanisms, both DRC and CAR do not have official national policies in place envisaging concrete exemptions from user fees, and the national reference documents, the Plan National de Développement Sanitaire (PNDS) and health sector transition plan, for both countries are not explicit about this. As shown in Table 2, household out-of-pocket payments amount to around 40% of total health expenditure in CAR and DRC, and out-of-pocket payments are even higher in Nigeria.

In the DRC, the PNDS stipulates that ‘national solidarity mechanisms’ should be developed, such as community-based health insurance, flat payments instead of fee-for-service-based user fees, and third-party payment mechanisms or equity funds [13]. In practice, several of these measures are implemented in an ‘informal’ way in some areas of the country but remain localised and externally led. For example, unofficial exemption policies exist for most preventative services (e.g., vaccination), which are de facto free and provided under a vertical approach [23]. Similarly, NGOs have experiences implementing programmes that include partial exemptions, equity funds for indigents or the introduction of flat fees [24]. Additionally, during acute crisis phases, humanitarian NGOs often introduce free care (total exemptions) for their catchment populations. These policies usually only last during the emergency phase and are found to be difficult to align with longer-term development approaches adopted by other external partners operating in those same areas, as exemplified by a case of Shabunda Health Zone in South Kivu in 2009 [9, 25].

In CAR, the national user-fee policy was modified during the height of the crisis in 2014. At the time, a policy of free healthcare for women (covering perinatal services), children and loosely defined ‘emergency’ services was instituted nationwide and implemented with external funding through all the different programmes and projects operating in the country [26]. However, this policy appeared to be a temporary emergency measure and was scaled down in stable areas, although it is in theory still in place in the most insecure areas (KIIs/FGDs).

Key informants described how, in Adamawa, in 2012 the Governor at the time declared maternal and child health services to be provided free of charge in the state. However, this policy has not been well implemented. The government initially provided free drugs for the services covered in order to support the exemption policy. However, this soon led to a large increase in service demand and facilities ran out of the drugs, which led them to charge for exempted services again. The policy was then abolished and no (selective) free-care policy was in place anymore at the time of research. A national insurance scheme exists but applies only to federal government workers [27].

PBF operated against this regulatory background, and in all three contexts PBF programmes introduced their own fee exemption mechanisms in addition to, or in the absence of, national policies on the matter. However, the methodology for selection of beneficiaries varied, and their effectiveness was often unclear.

In South Kivu, while overall PBF aimed at a reduction of user fees for all patients in agreement with the facilities and the local Health Committees, fee exemptions were initially not included in the PBF design. However, a mechanism to exempt the very poor (or indigents) from user fees through an equity fund (with reimbursement of payments waived by the purchasing agencies) was later introduced [28]. Nevertheless, subsequent project evaluations noted that these mechanisms were largely not functioning and not having the desired equitable effects [29, 30]. Additionally, in terms of equitable resource allocation between areas, little was done as there was no ‘equity bonus’ available to support more isolated and remote facilities (including those in conflict-affected areas) [28]. The equity bonus is a mechanism often introduced to increase the PBF envelope available for certain disadvantaged areas. More successful were the exemptions introduced for Internally Displaced People (IDPs) during times of acute crisis. In such times, the PBF design was adapted in order to allow facilities to provide free healthcare to IDPs by increasing the PBF bonus paid for services to them, while user fees continued to apply to local residents. This allowed providing free care to about 20,000 IDPs [25], and this model later served as example to other settings, including CAR [9, 31,32,33].

In CAR, a mechanism to exempt indigents from paying fees is in place under the Projet d’Appui au Système de Santé (PASS) programme, and health facilities receive compensation for the lost income as each indicator has two levels of bonus attached – a lower one for general patients, and a higher one for indigents [34]. However, selection of indigents is left open to communities to decide, without standardised criteria. Under the Bekou project, at the time of research around half of health facilities (those located in crisis-affected areas) still fell under the ‘total free care’ directive that was declared in 2014. For the other health facilities, a policy of targeted free care for maternal, neonatal and child health as well as indigents was in place [26]. Similar to the mechanism under PASS, Cordaid provides ‘equity bonuses’ to compensate for lost income to vulnerable groups (KIIs/FGDs).

In Adamawa State, PBF guidelines stipulated the introduction of fee exemptions for the very poor for outpatient consultations only. However, the identification of the very poor is done by the facilities, which have little incentive to exempt them. In crisis-affected areas, all care was provided for free to registered IDPs by the newly created outreach clinics in the IDP camps by providing additional funding to the facilities [9, 35]. In contrast with the example of Shabunda (South Kivu) above, in Adamawa State, the State Primary Healthcare (PHC) Development Agency in charge of purchasing PHC, provided essential leadership that enabled the coordinated response of humanitarian, development agencies and government, which were able to effectively share tasks (some providing in-kind support and others channeling funds to facilities via the PBF programme) and avoid duplication (KIIs/FGDs).

3.2 Basic Packages of Health Services, Health-Benefit Packages and PBF

An essential or basic package of health services (BPHS) is defined as a selection of cost-effective services and interventions that a government has identified as priority and aims to provide to the entire population. On the other hand, a health benefit package (or simply, benefit package) specifies an explicit set of services (usually a sub-set of the BPHS) and the cost sharing requirements for beneficiaries to access those services [36], often within specific schemes. BPHS play a critical role, especially in FCAS where health interventions and funding are multiple and fragmented, to help establish clear priorities, provide a sense of direction for all the intervening agencies and harmonise development partner activities [7, 37, 38]. At the same time, the World Health Organization stresses that it is essential that health benefit packages (i.e., who is entitled to what services, and what, if anything, they are they meant to pay at the point of service delivery) are clear and explicit, that the population is informed about them and that the promised benefits are aligned with provider payment mechanisms, so that providers are in the position to actually offer those services [39].

Similar to fee exemption, national health plans in all of the three countries mention benefit packages as one of the instruments in realising UHC, but their scope and applicability appears to vary. In DRC, regulations for the basic package are defined in the Minimum Package of Health Services (Paquet Minimum d’Activités, PMA) for health centres operating at primary level, and in the Complementary Package of Health Services (Paquet Complementaire d’Activités, PCA) for secondary hospitals [40]. However, the PMA and the PCA are defined broadly, and (as explained above) most services listed are subject to user fees [41], with variations across areas and services, depending on donors’ and NGOs’ interventions. Consequently no clear, single-benefit package in DRC exists and benefits vary across areas and individuals (depending on their employment and other factors) [36]. The situation is similar in the CAR where PMA and PCA exists, but benefits are fragmented and unclear (KIIs/FGDs). In Nigeria, the official BPHS includes 20 indicators at primary-care level (Minimum Package of Services, MPA) and 21 indicators at secondary level (Complementary Package of Services, CPA) [42]. However, this is not matched in the actual benefit package as most services are charged for and health insurance covers only a small population share, so that benefits remain fragmented, depending on individuals’ entitlements and resources [27].

In such contexts, by defining a list of indicators for which a payment (or bonus) is provided, PBF indirectly shapes the benefit package as facilities are encouraged to remove or reduce fees for those services. In South Kivu, PBF indicators were chosen based on the broad BPHS as defined by the MoH. However, the list of indicators as well as the bonus attached to each (which did not cover the full costs of providing the service, but only a portion to incentivise increased coverage) varied over time depending on the budget available and the funder(s)’ preferences, and only rarely were all services included (KIIs). The situation was similar in CAR, where the indicator list included in PBF programmes is based on the national BHPS, although not all services are included. There have also been efforts to harmonise the list between PASS and Fonds Bekou PBF programmes so that it is now common for the two, although payment rates differ between the programmes (KII/FGDs). In contrast, in Nigeria, the PBF pilot was meant to fund PHC services and therefore covered all services included in the BPHS. However, in the areas affected by the insurgency in Adamawa State, the list of indicators covered by PBF for the pre-existing facilities was reduced to include only seven to eight high-impact interventions from the MPA and the list of indicators for the newly created and subcontracted mobile clinics in the IDP camps was even more limited to five key interventions (antenatal care, deliveries, outpatient consultations, growth monitoring and immunization).

4 Discussion

Our analysis provides evidence on PBF’s integration within and impact on health-financing policies, focusing on three FCAS and two particular aspects, which are interconnected. However, the study has limitations and our findings are exploratory. The study draws on interviews whose number is relatively limited, due to availability and accessibility of respondents. Due to resource constraints, we could not record and transcribe all KIIs and FGDs. Data from these sources was mainly used to triangulate and contextualise information from the document review, to better understand the policy processes and not to elicit the experiences or perceptions of respondents. Some degree of respondent bias is possible because respondents were identified through contacts provided by implementing agencies. Although we captured the views of the MoH, and other governmental and non-governmental organisations, the sample is unbalanced towards those involved in PBF implementation, and we did not capture the views of the communities they serve. Additionally, some of the interviews were carried out remotely and we have not yet developed local research partnerships in all countries. Despite these important limitations, our research provides a first empirical analysis of the issue of the integration of PBF with two health-financing policies, focusing on FCAS where coordination is a challenge, and where a major evidence gap remains.

Free healthcare or fee-exemption policies were common across the study settings, especially during acute crisis phases. However, they were often ‘informal’ (i.e., not defined by the central government) and their implementation was not uniform in time, across geographical areas and in terms of benefits, based on external partners’ presence and preferences, and on the availability of funds. As exemptions or fee reductions (including PBF-related ones) were introduced locally and in an uncoordinated fashion, they resulted in tensions on the ground between actors adopting different approaches [8]. The resultant patchwork mirrors the implementation of user fee and benefit package guidelines that was observed in Tajikistan [43]. Moreover, exemption policies for the very poor introduced by PBF remain only partially successful often due to issues with beneficiaries’ identification, as also confirmed by other countries’ experiences [44, 45]. Our analysis also highlights that, although BPHS may be helpful in setting priorities and aligning support to health services [38], they were often too broad, and there was little or no effort to link BPHS with effective and clear benefits. In practice, selective support to specific services still determined the degree to which patients and communities could access health services. In this context, PBF programmes indirectly shaped the benefit package by defining a list of services for which a payment is provided and fees reduced or removed. However, often payment was linked to a limited number of interventions within the BPHS. Since rarely, across the three cases, the payment attached to each indicator covered the entire costs of providing that service (but rather a partial subsidy to incentivise service coverage), an argument could be made to subsidise the entire national BPHS, in order to promote better alignment and avoid leaving some services un-incentivised. However, under this approach concerns may exist about the level of payment, which would have been too low to represent a real incentive (especially in projects such as the one in South Kivu where budget per capita was overall low). Ultimately, it appears that the degree to which PBF service packages were aligned to the official national package of services varied across cases, and was influenced by factors such as development partners’ priorities, coordination among external actors and budgetary concerns during PBF implementation. Only in Adamawa State (in non-crisis-affected areas) did we note a substantial alignment of BPHS and PBF indicators (although not all BPHS services were included as PBF indicators), so that PBF contributed to standardise and improve the provision of primary care, even if outside of a free-care policy.

In general, and perhaps unsurprisingly, our findings suggest that PBF is better integrated and aligned with health-financing regulations where governmental leadership is stronger and where it is designed to fit pre-existing national structures. This was evident in the case of northern Nigeria where PBF is approached as a tool to channel funds for PHC, and remained so during acute crisis phases, providing structure and organisation to the system. This is not dissimilar to the case of Burundi where PBF is integrated with, and in support to, the national free healthcare policy [46]. In more precarious governance settings, with a weak regulatory environment and leadership such as the DRC and CAR, PBF remains implemented ‘vertically’ and (external) implementers can shape health governance, financing and service delivery as a de facto policymaker [9]. It must be noted that in the three cases we explored, PBF was implemented (at the time) as a pilot programme, rather than a national policy. This has implications and might in part explain why PBF has not been fully integrated with other policies [47, 48]. However, given that the policies we considered are cornerstones of the health-financing architecture, PBF programmes, even at pilot stage, should arguably have been designed to incorporate those principles. When this is not realised, and especially in the contexts where governance and government’s leadership are particularly weak, there is the risk of PBF operating as a parallel programme, potentially increasing fragmentation in health financing in general, as well as between areas supported by different donors. Our findings on the risks of fragmentation and parallel implementation are in line with the broader literature on health-financing reforms aiming to reach UHC. For example, Richard et al. [49] looked at maternal healthcare fee exemptions introduced in 11 countries of sub-Saharan Africa as a first step towards UHC and stressed the necessity of embedding such exemptions in a national framework to avoid further health-financing fragmentation. Looking specifically at PBF, our findings are consistent with work that was recently done on the impact of PBF on strategic purchasing in FCAS, which highlighted the importance of context – particularly the degree of stability and authority of government– the design of the PBF programme, and the potential for effective integration of PBF in existing systems as key factors behind differences in strategic purchasing effects noted [10]. They also reinforce a growing interest in the role of actors and the political economy of PBF and health-financing policies more generally; recent studies highlight how ideology, interests and networks shape the adoption and implementation of PBF, especially in FCAS, given capacity and funding asymmetries, which in turn affect not just access, equity and financial protection (i.e. the realisation of UHC), but also the material interests of the health-system stakeholders [50,51,52,53]. Finally, our findings are relevant to a wider debate about the role of PBF and relative importance of different mechanisms within it, including whether its main function is really to incentivise change or (especially within FCAS) to channel funds to under-resourced primary health systems [50, 54].

5 Conclusions

Integration of PBF within the existing health-financing mechanisms remains crucial to ensure long-term improvement of comprehensive and equitable service delivery. In particular, caution should be exercised with a long-term focus of performance-based financing on a small selection of indicators to avoid distortion of the delivery of a de facto benefit package and support the delivery of an integrated national primary-care package. Secondly, creating parallel PBF programmes may weaken existing health-financing mechanisms, or impede their development. Instead, the overhaul of the provider-purchaser-regulator relationship that PBF usually entails should be used as an opportunity to reform and strengthen existing structures and policies, such as harmonisation of fee exemption policies and aligned benefit packages.

Overall, we find that where national leadership is stronger, PBF is better integrated and in line with the health-financing policies and, during phases of acute crisis, can provide structure and organisation to the system. Where governmental stewardship is weaker, PBF may result in another parallel programme, potentially increasing fragmentation in health financing and inequalities between areas supported by different donors. These findings have important policy implications to ensure that health-financing interventions in fragile and humanitarian settings support not just immediate equitable access to healthcare but also longer-term health system strengthening and institution-building.

Change history

30 November 2020

.

References

Meessen B, Soucat A, Sekabaraga C. Performance-based financing: just a donor fad or a catalyst towards comprehensive health-care reform? Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:153–6.

Fritsche G, Soeters R, Meessen B. Performance-based financing toolkit. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2014.

Witter S, Fretheim A, Kessy F, Lindahl A. Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries (Review). Cochrane Collab. 2012.

Diaconu K, Falconer J, Facuseh AV, Fretheim A, Witter S. Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries (Update of a Cochrane review). Cochrane Collab. 2019.

Paul E, Albert L, Bisala BN, Bodson O, Bonnet E, Bossyns P, et al. Performance-based financing in low-income and middle-income countries: isn’t it time for a rethink? BMJ Glob Heal [Internet]. 2018;3:e000664. http://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000664.

Soucat A, Dale E, Mathauer I, Kutzin J. Pay-for-performance debate: not seeing the forest for the trees. Heal Syst Reform [Internet]. 2017;3:74–9.

Witter S. Health financing in fragile and post-conflict states: what do we know and what are the gaps? Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:2370–7.

Bertone MP, Falisse J-B, Russo G, Witter S. Context matters (but how and why?) A hypothesis-led literature review of performance based financing in fragile and conflict-affected health systems. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195301.

Bertone MP, Jacobs E, Toonen J, Akwataghibe N, Witter S. Performance-based financing in three humanitarian settings : principles and pragmatism. Confl Health. Conflict and Health; 2018;12:28.

Witter S, Bertone MP, Namakula J, Chandiwana P, Chirwa Y, Ssennyonjo A, et al. (How) does RBF strengthen strategic purchasing of health care? Comparing the experience of Uganda, Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2019;4:3.

Thompson R. Universal coverage in crisis-affected contexts: the rethoric and the reality. HSG Blog; 2017. http://www.healthsystemsglobal.org/blog/254/Universal-Health-Coverage-in-crisis-affected-contexts-the-rhetoric-and-the-reality.html. Accessed Oct 2017.

UN. Political Communiqué for the World Humanitarian Summit. 2016.

MSP. Plan National de Developpement Sanitaire 2011–2015. Kinshasa: Ministère de la Santé Publique. 2010.

NPHCDA. Implementation Guide. Integrating Primary Health Care Governance in Nigeria (PHC Under One Roof). Abuja: National Primary Health Care Development Agency. 2013.

Scholz R, Tietje O. Embedded case study methods: Integrating quantitative and qualitative knowledge. Sage Publications. 2002.

Yin R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 3rd edition. London: Sage Publications. 2003.

Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice. London: Sage Publications; 2003.

MacGregor H, Bloom G. Health systems research in a complex and rapidly changing context: ethical implications of major health systems change at scale. Dev World Bioeth. 2016;16:158–67.

Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, Murray SF, Brugha R. ‘Doing’ health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23:308–17.

MSP. Plan National de Developpement Sanitaire, 2016–2020: vers la couverture sanitaire universelle. Kinshasa: Ministere de la Sante Publique, Republique Democratique du Congo. 2016.

Federal Ministry of Health. National Health Policy 2016. Promoting the health of Nigerians to accelerate socio-economic development. 2016.

MSP. Plan de transition du Secteur Sante 2015–2017. Bangui: Ministere de la Sante et de la Population. Republique Centrafricaine. 2015.

Bertone MP, Lurton G, Mutombo PB. Investigating the remuneration of health workers in the DR Congo: implications for the health workforce and the health system in a fragile setting. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31:1143–51.

Dijkzeul D, Lynch CA. Supporting local health care in a chronic chrisis: management and financing approaches in the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Washington, DC: National Research Council—Roundtable on the Demography of Forced Migration, Committee on Population. 2006. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17441690600658792. Accessed Oct 2017.

Mushagalusa P. Contribution du programme de financement basé sur la performance au renforcement du système de santé dans un contexte de conflit. Cas des Zones de santé de Shabunda et Lulingu au Sud Kivu/RD Congo. 2012.

MSP. Directives relatives aux modalites d’application de la gratuite des soins dans les formation sanitaires publiques et privees à but non lucrat en RCA. Bangui: Ministere de la Sante Publique, des affaires sociales, de la promotion de genre et de l’action humanitaire. 2014.

Wright J. Essential Package of Health Services Country Snapshot: Nigeria. Bethesda, MD: Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc.; 2015.

Mayaka S, Muvudi M, Bertone MP, de Borman N. Le financement basé sur la performance en République Démocratique du Congo : comparaison de deux expériences pilotes. PBF CoP Working Paper Series—WP6. 2011.

Paalman M, Renaud A. Programme de Financement Basé sur la Performance Sud Kivu, République Démocratique du Congo. Évaluation externe. The Hague: Cordaid. 2010.

Sondorp E, Coolen A, Lodenstein E, Vaughan K. Evaluation du Programme de Renforcement de l’Etat dans le Sud Kivu, Basé sur la Performance, 2010–2012. Amsterdam: KIT; 2013.

Soeters R, editor. Performance-based financing in action. Theory and Instruments—Course Guide. 8th editio. The Hague: SINA Health. 2017.

Banga-Mingo JP, Kossi-Mazouka A, Soeters R, Love J. Evaluation du Financement basé sur la Performance dans la Préfecture de Nana Mambéré pendant la crise humanitaire 2013–2014. The Hague: Cordaid; 2014.

Shu Atanga J, Tsafack JP, Moussoume E, Kum Ghabowen I. How Performance Based Financing empowers the community and improves access to quality care in Eastern and North-Western Cameroon [Internet]. World Bank RBF Health. 2015. https://www.rbfhealth.org/sites/rbf/files/HowPBFEmpowerstheCommunityinCameroon.pdf. Accessed Oct 2017.

PASS/MSHPP. Manuel d’execution du financement base sur la performance (FBP) en Republique Centrafricaine. Bangui: Projet d’Appui au Systeme de Sante - Ministere de la Santé, de l’Hygiene Publique et de la Population. 2017.

Hyeladzira G, Mbunya S, Ihebuzor N, Olubajo L, Margwa P. Building Resilient Systems through Performance-Based Financing in Fragile & Conflict-affected States: Case of Insurgency Affected Districts in Adamawa State, Nigeria. Presentation at AfHEA 2016 conference. 2016.

Mathew J, Abiodun O. The Essential Package of Health Services and Health Benefit Plans in Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bethesda, MD: Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc. 2017.

Eldon J, Waddington C, Hadi Y. Health Systems Reconstruction: Can it Contribute to State-building?. London: HLSP Institute; 2008.

Newbrander W, Waldman RJ, Shepherd-Banigan M. Rebuilding and strengthening health systems and providing basic health services in fragile states. Disasters. 2011;43:639–60.

Kutzin J, Witter S, Jowett M, Bayarsaikhan D. Developing a national health financing strategy: a reference guide. Geneva: World Health Organization—Health Financing Guidance Series No 3. 2017.

MSP. Recueil des Normes de la Zone de Santé. Kinshasa: Ministere de la Santé Publique. 2006.

Wright J. Essential Package of Health Services Country Snapshot: The Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bethesda, MD: Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc. 2015.

Federal Ministry of Health. Project Implementation Manual. Nigeria State Health Investment Project (NSHIP). Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health; 2012.

Jacobs E. The politics of the basic benefit package health reforms in Tajikistan. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2019;4:14.

De Allegri M, Bertone MP, McMahon S, Mounpe Chare I, Robyn PJ. Unraveling PBF effects beyond impact evaluation: results from a qualitative study in Cameroon. BMJ Glob Heal. 2018;3:e000693.

Flink I, Ziebe R, Vagaï D, van de Looij F, van ‘T Riet H, Houweling T. Targeting the poorest in a performance-based financing programme in northern Cameroon. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31:767–76.

Falisse J-B, Ndayishimiye J, Kamenyero V, Bossuyt M. Performance-based financing in the context of selective free health-care: an evaluation of its effects on the use of primary health-care services in Burundi using routine data. Health Policy Plan. 2014;30:1251–60.

Shroff ZC, Bigdeli M, Meessen B. From scheme to system (part 2): findings from ten countries on the policy evolution of results-based financing in health systems. Heal Syst Reform. 2017;3:137–47.

Meessen B, Shroff ZC, Por I, Bigdeli M. From scheme to system (Part 1): notes on conceptual and methodological innovations in the multicountry research program on scaling up results-based financing in health systems. Heal Syst Reform. 2017;3:129–36.

Richard F, Antony M, Witter S, Kelley A, Meessen B, Sieleunou I. Fee exemption for maternal care in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of 11 countries and lessons for the region. Glob Heal Gov. 2013;VI.

Witter S, Chirwa Y, Chandiwana P, Munyati S, Pepukai M, Bertone MP. The political economy of results-based financing: the experience of the health system in Zimbabwe. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2019;4.

Bertone MP, Wurie HR, Samai MH, Witter S. The bumpy trajectory of performance-based financing for healthcare in Sierra Leone: agency, structure and frames shaping the policy process. Global Health. 2018;14:99.

Gautier L, De Allegri M, Ridde V. How is the discourse of performance-based financing shaped at the global level? A poststructural analysis. Global Health. 2019;15:6.

Sparkes SP, Bump JB, Özçelik EA, Kutzin J, Reich MR. The Political Economy of Health Financing Reform: Analysis and Strategies to Support Universal Health Coverage. Heal Syst Reform. 2019.

Paul E, Renmans D. Performance-based financing in the heath sector in low- and middle-income countries: Is there anything whereof it may be said, see, this is new? Int J Health Plann Manage. 2017;Advanced A.

Soeters R, Peerenboom PB, Mushagalusa P, Kimanuka C. Performance-based financing experiment improved health care in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Health Aff. 2011;30:1518–27.

Mangala A, Mutuapikay K, Soeters R. Etude de Faisabilité pour le programme « Achat de Performance » dans les Zones de Santé du District Sanitaire Nord du Sud Kivu, 2006–2009. Bukavu: Cordaid; 2005.

Dukhan S. Assistance Technique de démarrage du projet ‘Amélioration des soins de santé de base dans les régions sanitaires 1&6 (ASSB1&6) en République Centrafricaine.’ Bangui: Programme FED de l’Union européenne en République Centrafricaine. 2007.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the key informants who participated in the study, Cordaid and AEDES, which provided access for data collection at country level and shared documents, Valéry Ridde and the participants of the African Economic Research Council’s Final Review Workshop (31 May–1 June 2018) for their comments and suggestions, and Heloise Widdig who provided valuable research assistance.

Author Contributions

Under Sophie Witter’s (SW) lead, all authors contributed to the design of the study. Maria Paola Bertone (MPB) collected data for the DRC case study, Eelco Jacobs (EJ) for the CAR, Jurrien Toonen (JT) and Ngozi Akwataghibe for Nigeria. MB, EJ, JT and SW analysed the data and discussed the findings together. EJ drafted the manuscript, on which all other authors provided comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Panel of Queen Margaret University (Edinburgh). Informed consent was obtained from every interviewee and FGD participant, after they had been informed of the study objectives and been offered the possibility to refrain from answering or withdraw from the interview/discussion at any point without further consequences. The authors declare that they have no competing interests. We acknowledge the financial support of The UK Department for International Development (DFID) through the ReBUILD grant, as well as the support of the African Economic Research Council. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect official policies of the UK government or of our funders.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset (i.e., interview notes, recordings and transcripts) generated and analysed for this study is not publicly available in order to preserve the anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jacobs, E., Bertone, M.P., Toonen, J. et al. Performance-Based Financing, Basic Packages of Health Services and User-Fee Exemption Mechanisms: An Analysis of Health-Financing Policy Integration in Three Fragile and Conflict-Affected Settings. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 18, 801–810 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-020-00567-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-020-00567-8