Abstract

Background

There is interest in the extent to which valuations of health may differ between different countries and cultures, but few studies have compared preference values of health states obtained in different countries.

Objective

We sought to estimate and compare two directly elicited valuations for SF-6D health states between the Japan and UK general adult populations using Bayesian methods.

Methods

We analysed data from two SF-6D valuation studies where, using similar standard gamble protocols, values for 241 and 249 states were elicited from representative samples of the Japan and UK general adult populations, respectively. We estimate a function applicable across both countries that explicitly accounts for the differences between them, and is estimated using data from both countries.

Results

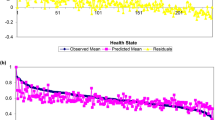

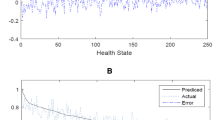

The results suggest that differences in SF-6D health-state valuations between the Japan and UK general populations are potentially important. The magnitude of these country-specific differences in health-state valuation depended, however, in a complex way on the levels of individual dimensions.

Conclusion

The new Bayesian non-parametric method is a powerful approach for analysing data from multiple nationalities or ethnic groups, to understand the differences between them and potentially to estimate the underlying utility functions more efficiently.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brazier JE, Ratcliffe J, Tsuchiya A, Solomon J. Measuring and valuing health for economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72.

Torrance GW, Feeny DH, Furlong WJ, Barr RD, Zhang Y, Wang QA. Multi-attribute utility function for a comprehensive health status classification system: Health Utilities Index Mark 2. Med Care. 1996;34(7):702–22.

Feeny DH, Furlong WJ, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zenglong Z, Depauw S, Denton M, Boyle M. Multi-attribute and single-attribute utility function for the Health Utility Index Mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40(20):113–28.

Hawthorne G, Richardson G, Atherton Day N. A comparison of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) with four other generic utility instruments. Ann Med. 2001;33:358–70.

Brazier JE, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21:271–92.

Revicki DA, Leidy NK, Brennan-Diemer F, Sorenson S, Togias A. Integrating patients’ preferences into health outcomes assessment: the multiattribute asthma symptom utility index. Chest. 1998;114(4):998–1007.

Brazier JE, Czoski-Murray C, Roberts J, Brown M, Symonds T, Kelleher C. Estimation of a preference-based index from a condition specific measure: the King’s Health Questionnaire. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(1):113–26.

Yang Y, Brazier JE, Tsuchiya A, Coyne K. Estimating a preference-based index from the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire. Value Health. 2009;12:159–66.

Yang Y, Brazier JE, Tsuchiya A, Young T. Estimating a preference-based index for a 5-dimensional health state classification for asthma derived from the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Med Decis Making. 2011;31:281–91.

Drummond MF, Sculpher M, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications; 2005.

Cruz LC, Camey SA, Hoffman JF, Rowen D, Brazier JE, Fleck MP, Polanczyk CA. Estimating the SF-6D value set for a Southern Brazilian Population. Value Health. 2011;14(5):S108–14.

Ferreira LN, Ferreira PL, Brazier J, Rowen D. A Portugese value set for the SF-6D. Value Health. 2010;13(5):624–30.

Brazier JE, Fukuhara S, Roberts J, Kharoubi S, et al. Estimating a preference-based index from the Japanese SF-36. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(12):1323–31.

McGhee SM, Brazier J, Lam CLK, Wong LC, Chau J, Cheung A, Ho A. Quality adjusted life years: population specific measurement of the quality component. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;17(Suppl 6):S17–21.

Norman R, Viney R, Brazier J, Burgess L, Cronin P, King M, et al. Valuing SF-6D health states using a discrete choice experiment. Med Decis Making. 2013;34(6):773–86.

Johnson JA, Luo N, Shaw JW, Kind P, Coons SJ. Valuations of EQ-5D health states; are the United States and United Kingdom different. Med Care. 2005;43:221–8.

Badia X, Roset M, Herdman M, Kind P. A comparison of United Kingdom and Spanish general population time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states. Med Decis Making. 2001;20:7–16.

Tsuchiya A, Ikeda S, Ikegami N, Nishimura S, Sakai S, Fukuda T, Hamashima C, Hisashige A, Tamura M. Estimating an EQ-5D population value set: the case of Japan. Health Econ. 2002;11:341–53.

Ferreira LN, Ferreira PL, Rowen D, Brazier J. Do Portuguese and UK health state values differ across valuation methods? Qual Life Res. 2011;20(4):609–19.

Kharroubi SA, O’Hagan A, Brazier JE. A comparison of United States and United Kingdom EQ-5D health state valuations using a nonparametric Bayesian method. Stat Med. 2010;29:1622–34.

Kharroubi SA, Brazier JE, McGhee S. A comparison of Hong Kong and United Kingdom SF-5D health state valuations using a nonparametric Bayesian method. Value Health. 2014;17(4):397–405.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83.

Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance GW, Barr R, Horsman J. Guide to design and development of health state utility instrumentation. Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis Paper 90-9, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, 1990.

Patrick DL, Starks HE, Cain KC, Uhlmann RF, Pearlman RA. Measuring preferences for health states worse than death. Med Decis Making. 1994;14:9–18.

Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, Hsiao A, Kurokawa K. Translation, adaptation and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;51:1037–44.

Fukuhara S, Ware JE, Kosinski M, Wada S, Gandek B. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1045–53.

Kharroubi SA, O’Hagan A, Brazier JE. Estimating utilities from individual health state preference data: a nonparametric Bayesian approach. Appl Stat. 2005;54:879–95.

Kharroubi SA, O’Hagan A, Brazier JE. Modelling covariates for the SF-6D Standard Gamble health state preference data using a nonparametric Bayesian method. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1242–52.

Kharroubi SA, McCabe C. Modelling HUI 2 health state preference data using a nonparametric Bayesian method. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:875–87.

Lam CL, Brazier J, McGhee SM. Valuation of the SF-6D health states is feasible, acceptable, reliable, and valid in a Chinese population. Value Health. 2008;11:295–303.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Prof. Tony O’Hagan for his continual support, useful guidance and invaluable insights during the manuscript preparation and J. Brazier, J. Roberts, S. Fukuhara, Y. Yamamoto, S. Ikeda, J. Doherty and K. Kurokawa who were investigators in the original Japan valuation survey.

Finally, the author confirms that there are no conflicts of interest and/or financial disclosures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Modification to \( \varvec{\beta}_{{\mathbf{0}}} \) and \( \varvec{\beta}_{{\mathbf{1}}} \) vectors given in (2) and (3)

Appendix: Modification to \( \varvec{\beta}_{{\mathbf{0}}} \) and \( \varvec{\beta}_{{\mathbf{1}}} \) vectors given in (2) and (3)

The SF-6D health state descriptive system is exactly the same for the UK [6] and Japan (Table 1) except for the role limitations dimension, i.e. when d = 2. The result is that

This corresponds to the second parameter in the β - vector, i.e. β 2. To model this we suggest the following:

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Japan | 0 | β 2 | 2β 2 | 3β 2 | 4β 2 |

UK | 0 | β* | γ* | β* + γ* |

Note that this dimension is a bit anomalous in the UK definition of levels. Level 2 is one type of restriction, level 3 is a different type of restriction and level 4 is no type. Therefore, we have two parameters β* and γ* for the loss of quality of life for each type of restriction.

Let β 0 be the vector of parameters that represent the UK, which comprise the constant term, the slopes for dimensions 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and the new pair of parameters for dimension 2. Let β 1 be the extra parameters that we need for Japan, which are increments to the constant terms and to the slopes in dimensions 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and the new slope in dimension 2. Let β be the combination of these two vectors. Now we write the expectation of \( u_{c} ({\mathbf{x}})\;{\text{as}}\;\varvec{\beta}^{{\prime }} {\mathbf{z}} \), where the vector z is a suitable function of the vector x of levels. For instance if x = (1, 2, 3, 4, 2, 1) and c = 0 then \( {\mathbf{z}} \) needs to be (1, 1, 1, 0, 3, 4, 2, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0), where the first 1 is multiplying the UK constant term, the second 1 is multiplying the UK slope parameter for dimension 1, the third 1 is multiplying the β* parameter for UK dimension 2, the first 0 is multiplying the γ* parameter for UK dimension 2, the following 3, 4, 2, 1 multiply the UK slope parameters for dimensions 3–6 and the remaining 7 zeroes multiply the Japanese parameters. For the same x and c = 1, z should be (1, 1, 0, 0, 3, 4, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 2, 1). This implies that if x = (1, 1, 3, 4, 2, 1), then

whereas if x = (1, 4, 3, 4, 2, 1), we get

Therefore, UK level 4 of dimension 2 has expectation β* + γ*.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kharroubi, S.A. A Comparison of Japan and UK SF-6D Health-State Valuations Using a Non-Parametric Bayesian Method. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 13, 409–420 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-015-0171-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-015-0171-8