Abstract

Background

Access to safe drinking water has been on the global agenda for decades. The key to safe drinking water is found in household water treatment and safe storage systems.

Objective

In this study, we assessed rural and urban household demand for a new gravity-driven membrane (GDM) drinking-water filter.

Methods

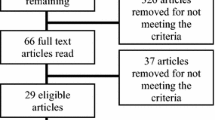

A choice experiment (CE) was used to assess the value attached to the characteristics of a new GDM filter before marketing in urban and rural Kenya. The CE was followed by a contingent valuation (CV) question. Differences in willingness to pay (WTP) for the same filter design were tested between methods, as well as urban and rural samples.

Results

The CV follow-up approach produces more conservative and statistically more efficient WTP values than the CE, with only limited indications of anchoring. The effect of the new filter technology on children with diarrhea is among the most important drivers behind choice behavior and WTP in both areas. The urban sample is willing to pay more in absolute terms than the rural sample irrespective of the valuation method. Rural households are more price sensitive, and willing to pay more in relative terms compared with disposable household income.

Conclusion

A differentiated marketing strategy across rural and urban areas is expected to increase uptake and diffusion of the new filter technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The average exchange rate (Ksh to US$) in the month of January 2012 was 0.0114.

The outcome of the likelihood ratio (LR) test when comparing the preference parameters between the two models for Nessuit and Nakuru, whilst keeping the scale parameter constant, was 27.4 (p < 0.002). The equality of scale parameters is rejected at p < 0.01 by the same test (LR = 11.39, 1 degree of freedom).

Attribute attendance was also tested by estimating latent class models for both subsamples using the so-called 2K model in NLOGIT 5, and we found that a larger share of the respondents in the rural sample did not consider storage capacity in their choices. The attribute flow rate was ignored in both samples, as is reflected in its statistical insignificance.

This was the only variable that also produced a significant interaction effect with the diarrhea choice attribute in the urban sample.

The standardized Mann–Whitney test statistic comparing the two contingent valuation willingness-to-pay values equals −11.723 (p < 0.0001).

Test results are available from the authors upon request.

The Mann–Whitney test statistic comparing the central tendency of the relative share of willingness to pay with household income between the two samples equals −7.475 (p < 0.0001).

References

WHO-UNICEF. Progress in drinking water and sanitation: 2012 update. New York: WHO and UNICEF; 2012.

Government of Kenya. Population and housing census results, Ministry of Planning and Vision 2030. Nairobi: Government of Kenya; 2009.

USAID, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Demographic and health survey. Nairobi: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2009.

Murage EW, Ndingu AM. Quality of water the slum dwellers use, the case of a kenyan slum. J Urban Health. 2007;84:829–38.

Peter-Varbanets M, Hammes F, Vital M, Pronk W. Stabilization of flux during dead-end ultra-low pressure ultrafiltration. J Water Res. 2010;44:3607–16.

Tornheim JA, Manya AS, Oyando N, Kabaka S, O’Reilly CE, Breiman RF, Feikin DR. The epidemiology of hospitalization with diarrhea in rural Kenya: the utility of existing health facility data in developing countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e499–505.

Mirza MN, Caulfield LE, Black RE, Macharia WM. Risk factors for diarrheal duration. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:776–85.

Sobsey MD. Managing water in the home: accelerated health gains from improved water supply. Water, Sanitation and Health, Department of Protection of the Human Environment. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2002.

Peter-Varbanets M, Zurbrügg C, Swartz C, Pronk W. Decentralized systems for potable water and the potential of membrane technology. J Water Res. 2009;43:245–65.

Peter-Varbanets M, Margot J, Traber J, Pronk W. Mechanisms of membrane fouling during ultra-low pressure ultrafiltration. J Membr Sci. 2011;377:42–53.

Hanley N, Mourato S, Wright RE. Choice modelling approaches: a superior alternative for environmental valuation? J Econ Surv. 2001;15(3):435–62.

Birol E, Koundouri P, editors. Choice experiments informing environmental policy: a European perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2008.

Carson RT, Louviere J. A common nomenclature for stated preference elicitation approaches. Environ Resour Econ. 2011;49(4):539–59.

Hensher DA, Shore N, Train K. Water supply security and willingness to pay to avoid drought restrictions. Econ Rec. 2006;82(256):56–66.

Hasler B, Lundhede T, Martinsen L, Neye S, Schou JS. Valuation of groundwater protection versus water treatment in Denmark by choice experiments and contingent valuation. Technical report no. 543. Denmark: National Environmental Research Institute (NERI), Ministry of the Environment; 2005.

Yoshida K, Kanai S. Estimating the economic value of improvements in drinking water quality using averting expenditures and choice experiments. Multilevel Environmental Governance for Sustainable Development, Discussion Paper No. 07-02. 2007.

Tarfasa S, Brouwer R. Estimation of the public benefits of urban water supply improvements in Ethiopia: a choice experiment. Appl Econ. 2013;45(9):1099–108.

Null C, Kremer M, Miguel E, Garcia Hombrados J, Meeks R, Peterson Zwane A. Willingness to pay for cleaner water in less developed countries: systematic review of experimental evidence. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie), Systematic Review 006; 2012.

Briscoe J, Furtado de Castro P, Griffen C, North J, Olsen O. Toward equitable and sustainable rural water supplies: a contingent valuation study in Brazil. World Bank Econ Rev. 1990;4(2):115–34.

Griffin CC, Briscoe J, Singh B, Ramasubban R, Bhatia R. Contingent valuation and actual behavior: predicting connection to new water systems in the state of Kerala, India. World Bank Eco Rev. 1995;9:373–95.

Venczel L. Evaluation and application of a mixed oxidant disinfectant system for waterbourne disease prevention. PhD dissertation submitted to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1997.

Goldblatt M. Assessing the effective demand for improved water supplies in informal settlements: a willingness to pay survey in Vlakfontein and Finetown, Johannesburg. Geoforum. 1999;30(1):27–41.

Raje RV, Dhobe PS, Deshpande AW. Consumer’s willingness to pay more for municipal supplied water: a case study. Ecol Econ. 2002;42:391–400.

Whittington D, Pattanayak SK, Yang J, Bal Kumar KC. Household demand for improved piped water services: evidence from Kathmandu, Nepal. Water Policy. 2002;4:531–56.

Clasen T, Brown J, Collin S, Suntura O, Cairncross S. Reducing diarrhea through the use of household-based ceramic water filters: a randomized, controlled trial in rural Bolivia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70(6):651–7.

Ahmad J, Goldar B, Misra S. Value of arsenic-free drinking water to rural households in Bangladesh. J Environ Manag. 2005;74(2):173–85.

Casey JF, Kahn JR. Willingness to pay for improved water service in Manaus Amazonas, Brazil. Ecol Econ. 2006;58(2):365–72.

Vasquez WF, Mozumder P, Hernandez-Arce J, Berrens RP. Willingness to for safe drinking water: evidence from Parral Mexico. J Environ Manag. 2009;90(11):3391–400.

Khan N, Brouwer R, Yang H. Household’s willingness to pay for arsenic safe drinking water in Bangladesh. J Environ Manag. 2014;143:151–61.

US EPA 2003. Children’s health valuation handbook. EPA report 100-R-03-003.

Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, Boschi-Pinto C, Black RE. Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:220.

Scapecchi P. Valuation differences between adults and children. In: Economic valuation of environmental health risks to children. OECD. 2006. p. 79–119.

Cameron TA, DeShazo JR, Johnson JA. The effect of children on adult demands for health-risk reductions. J Health Econ. 2010;29:364–76.

Hammitt JK, Haninger K. Valuing fatal risks to children and adults: effects of disease, latency, and risk aversion. J Risk Uncertain. 2010;40:57–83.

Hynes S, Campbell D, Howley P. A holistic vs. an attribute-based approach to agri-environmental policy valuation: Do welfare estimates differ? J Agric Econ. 2011;62(2):305–29.

Rolfe J, Windle J. The sequencing effects of paired experiments with choice experiments and contingent valuation. Istanbul: Paper presented at the World Congress of Environmental and Resource Economists; 2014.

Scarpa R. Contingent valuation versus choice experiments: Estimating the benefits of environmentally sensitive areas in Scotland: comment. J Agric Econ. 2000;51(1):122–8.

Cameron TA, Poe GL, Ethier RG, Schulze WD. Alternative nonmarket value-elicitation methods: are the underlying preferences the same? J Environ Econ Manag. 2002;44(3):391–425.

Foster V, Mourato S. Elicitation format and sensitivity to scope. Environ Resour Econ. 2003;24(2):141–60.

Mogas J, Riera P, Bennett J. A comparison of contingent valuation and choice modelling with second-order interactions. J For Econ. 2006;12(1):5–30.

van der Kroon B, Brouwer R, van Beukering P. The impact of the household decision environment on fuel choice behavior. Energy Econ. 2014;44:236–47.

Nakuru District Statistical Office: Nakuru; 2012.

Yillia PT, Kreuzinger N, Mathooko JM. The effect of in-stream activities on the Njoro River, Kenya. Part II: microbial water quality. Phys Chem Earth Parts A/B/C. 2008;33:729–37.

Silas K, Moses LK, Mwaniki NEN, Okemo PO. Bacteriological quality and diarrhoeagenic pathogens on river Njoro and Nakuru municipal water, Kenya. Int J Biotechnol Mol Biol Res. 2011;2(9):150–62.

Kiruki S, Limo M, Njagi E, Paul O. Bacteriological quality and diarrhoeagenic pathogens on River Njoro and Nakuru Municipal water, Kenya. Int J Biotechnol Mol Biol Res. 2011;2:150–62.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya facts and figures 2012. Nairobi; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2012.

Swait J, Louviere J. The role of the scale parameter in the estimation and comparison of multinomial logit models. J Mark Res. 1993;30(3):305–14.

Bhat CR. Quasi-random maximum simulated likelihood estimation of the mixed multinomial logit model. Transp Res Part B. 2001;35:677–93.

Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis: a primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Krinsky I, Robb AL. On approximating the statistical properties of elasticities. Rev Econ Stat. 1986;68:715–9.

Poe GL, Giraud KL, Loomis JB. Computational methods for measuring the difference of empirical distributions. Am J Agric Econ. 2005;87(2):353–65.

Hensher DA, Shore N, Train K. Households’ willingness to pay for water service attributes. Environ Resour Econ. 2005;32(4):509–31.

Jin J, Wang Z, Ran S. Comparison of contingent valuation and choice experiment in solid waste management programs in Macao. Ecol Econ. 2006;57(3):430–41.

Ryan M, Watson V. Comparing welfare estimates from payment card contingent valuation and discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2009;18(4):389–401.

Whitty JA. Insensitivity to scope in contingent valuation studies: new direction for an old problem. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2012;10(6):361–3.

Søgaard R, Lindholt J, Gyrd-Hansen D. Insensitivity to scope in contingent valuation studies: reason for dismissal of valuations? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2012;10 (6):397-405.

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by the Netherlands Organisation for International Cooperation in Higher Education (Nuffic) for Fumbi Crescent’s stay at Eawag is gratefully acknowledged. Roy Brouwer carried out this work as part of his appointment at Eawag.

Conflict of interest

Roy Brouwer, Fumbi Crescent Job, Bianca van der Kroon, and Richard Johnston confirm that no conflicts of interest exist in relation to the publication of this article.

Contributions of the Individual Authors

Roy Brouwer contributed to the design of the questionnaire, design of the CE, and analysis of the collected data, and is the main author of the paper. Fumbi Crescent Job helped with the design of the questionnaire and was responsible for the data collection. He carried out the pre-tests together with Bianca van der Kroon, and entered the data in a database. Bianca van der Kroon helped with the design of the CE, pretesting of the questionnaire, and contributed to the analysis of the data and helped with the writing of the paper. Richard Johnston helped with the design of the questionnaire.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Annex

Annex

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brouwer, R., Job, F.C., van der Kroon, B. et al. Comparing Willingness to Pay for Improved Drinking-Water Quality Using Stated Preference Methods in Rural and Urban Kenya. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 13, 81–94 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-014-0137-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-014-0137-2