Abstract

Trade in processed small pelagic fish and informal cross-border trade (ICBT) are linked to livelihood activities in West Africa. Although these fish products are being traded informally in West Africa, research on this topic is limited. This study builds on a multi-partner supported ‘FishTrade’ initiative in Africa to illuminate the volume and value of informal fish trade across the Ghana–Togo–Benin (GTB) borders, and the socio-demographic determinants supporting participation and profitability in this trade. We used a structured survey and focus group interviews to obtain data from women fish traders, who handle the entire fish trade in three major Ghanaian markets where ICBT activities are concentrated. Our results showed ICBT across these borders constitutes significant economic and livelihood potential, estimated at about 6000 MT in volume and US$14 million in market value per annum. Furthermore, socio-demographic factors, such as fish traders’ years of experience and membership in an unofficial market cooperative, positively influence participation and profitability, but access to market information negatively affects participation. However, geographical distance, large household size and access to micro-finance negatively affect ICBT profitability. Our findings illuminate that consumers’ purchasing power, fish taste and preference, ICBT’s economic opportunities and a shared heritage and connection significantly influence this form of trading along the GTB borders. We conclude that ICBT in these small pelagic processed fish represents untapped potential for local livelihood and highlight the need for further research on this topic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, more than 116 million people are directly or indirectly employed in the fisheries sector, among whom 90% are engaged in small-scale fishing activities and value chains (Kelleher et al. 2012; Teh and Sumaila 2013; Mancha-Cisneros et al. 2019). Small-scale fisheries (SSFs), specifically those dealing in small pelagic fish, contribute significantly to livelihoods, poverty alleviation, food security and wellbeing for people in low- and middle-income countries (Béné and Friend 2011; Sowman et al. 2014; Nyiawung et al. 2022). For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa, small pelagic fish provide 15–19% of the population’s intake of animal protein and related micronutrients, minerals and fatty acids (Chan et al. 2019). However, the potential and contribution of these fish, specifically the low-cost products from processing these fish, are often underreported because of the limited data available or because of data unavailability (Belhabib et al. 2016; Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO] 2017).

The formal and informal trading and distribution of processed low-cost small pelagic fish represent significant income-generating opportunities for women fish traders in low- and middle-income countries (Marquette et al. 2002; Mills et al. 2011; Neiland 2006). Women constitute approximately 47% of the labour workforce involved in fisheries-related economic activities (FAO 2017), contributing an estimated market value of US$5.6 billion and providing support in activities across the fish value chain (Harper et al. 2020). In West Africa, women coordinate the small pelagic fish value chain’s labour arrangements for fish processing, marketing and distribution. Men are primarily engaged in pre-harvesting and fish harvest activities (Appiah et al. 2021; Harper et al. 2013; Thorpe et al. 2014). However, despite compelling evidence that women have an active role in the fish value chain (FAO 2017; Harper and Kleiber 2019), scholarly accounts of their participation in this chain are less illuminated compared with those of men in low-and-middle-income countries (Lawless et al. 2019, 2021; Uduji and Okolo-Obasi 2020). Moreover, the unique role of women fish traders in the informal cross-border trade (ICBT) in West Africa remains underreported and overlooked in policy discourses.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, ICBT constitutes a hazy form of trading activities, outperforming, in some cases, formal cross-border trade (Ackello-Ogutu and Echessah 1997; Titeca 2012). ICBT has contributed significantly to economic activities at the national level and economic integration at the regional level (Nshimbi and Moyo 2017; Titeca and De Herdt 2010). ICBT activities consist of relatively small consignments of goods, handled mainly by individuals and small to medium-sized businesses (Golub 2015). This trade is coordinated by people without formal business licenses and leads to tax evasion and other formal cross-border trade irregularities (Lesser and Leeman 2009). ICBT activities in West Africa are driven by market, economic and infrastructure factors (Fadahunsi and Rosa 2002). For instance, informal trading activities evade taxes and customs charges, resulting in a pricing advantage for customers over formally traded goods. In addition, the lack of and (or) scarcity of specific commodities (such as fish) across different geographical boundaries, and exchange rate gains from trading in neighbouring nations contribute to promoting ICBT (Lesser and Leeman 2009; Little 2007). The economic climate in West Africa, characterised by rising unemployment numbers, also encourages people, especially those in border communities, to participate in ICBT for their livelihoods (Faleye 2014). They consider ICBT a viable economic option (Peberdy 2000; Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa [COMESA] 2007), particularly because it requires minimum capital investment (Akinboade 2005).

In West Africa, women are the primary ICBT actors in the processed small pelagic fish trade. They market and distribute these processed fish, such as smoke and dried marine anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus), sardinella (Sardinella aurita) and herring (Clupeidae), and a small proportion of catfish (Clarias gariepinus) from inland water bodies (Ayilu et al. 2016). Yet, the scale and importance of these trade activities are seldomly acknowledged, are poorly understood, and have received insufficient scholarly attention in the West African context. Most studies on fisheries tend to focus on fishers and ignore the actors and the processes in the midstream and downstream sectors of the value chain, including domestic trade and cross-border trade (Belton et al. 2022). The aspects of ICBT, particularly for small-scale fisheries, deserves the needed consideration by academics and policymakers because they provide significant economic and livelihood potentials. In this study, we illuminate the ICBT in processed small pelagic fish in West Africa, which is coordinated mainly by women. This study highlights three important aspects: (1) the trade volumes and values of ICBT in processed small pelagic fish along the Ghana–Togo–Benin (GTB) borders, (2) the socio-demographic determinants of trade participation and profitability and (3) socioeconomic factors influencing ICBT activities (i.e. consumers’ purchasing power, business opportunities, shared heritage and connections and taste and preference). The study adds to the existing literature on fisheries by providing a picture of the small pelagic fish trade in West Africa and discusses the ways in which the trade and commodity flows are intertwined with social cultural and economic structures and processes (Belton et al. 2022; Fröcklin et al. 2013).

This study is the outcome of the ‘FishTrade’ project financed by WorldFish, African Union Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources, New Partnership for Africa’s Development and the European Union. The FishTrade project assisted regional and pan-African organisations in integrating intra-regional fish trade into their development and food security agendas. Our study illuminates the economic viability of the processed small pelagic fish trade in the SSF value chain in the West African subregion. Notably, ICBT in these processed fish is a key source of food, nutritional livelihood and business opportunity in the West African fish value chain.

The paper is divided into four sections. The next section “Methodology” presents the research methods and data analysis, including the empirical model specification, followed by the “Results”. We then provide a discussion (“Discussion”) of our results, and finally, the “Conclusion” discusses the need for more research to illuminate the potential and contribution of ICBT in small pelagic in small-scale fisheries.

Methodology

We employed a mixed methods approach for data collection. Quantitative techniques were used to ascertain the volume and value of ICBT transactions and explore the various socio-demographic determinants associated with ICBT. The qualitative data, collected through in-depth focus group interviews with participants, were used to identify the intrinsic and extrinsic factors influencing the trade flow. This methodological approach was adopted because it provides a more holistic understanding of the small pelagic fish trade in terms of scale, magnitude and the ICBT socio-demographic determinants. In addition, we use peer-reviewed, and grey published materials to support our discussions and arguments. The rest of this “Methodology” section presents the study sites, the data collection and analysis methods, the estimation of trade volume and value and the model specifications.

Study sites

The study was conducted in the three largest fish markets in Ghana: Denu, Dambai and Accra — Tuesday market (see Fig. 1). The markets were chosen as the means for data collection because it was difficult to meet traders at the border checkpoint. ICBT traders tend to avoid study teams at border crossings, for they assume the teams are border authorities disguising themselves as researchers. Although Ghana has numerous local marketplaces, these three markets are the biggest in terms of the fish trade and principally for cross-border fish traders to neighbouring Togo and Benin. The traders are mostly Togolese and Beninese, with a small number of Ghanaians residing along the border. They purchase the fish in these markets from their Ghanaian merchant partners and sell to retail agents and consumers in Togo and Benin.

Accra — Tuesday Market

Accra Tuesday market is situated in the heart of Ghana’s capital city, Accra, adjacent to the Atlantic Ocean. The market draws traders from all over Ghana and neighbouring Togo and Benin. It is open for business every Tuesday, earning its nickname ‘Tuesday market’. The traders belong to a small informal market group that promotes social and economic welfare activities. The majority of market participants are small to medium-sized traders and wholesale merchants. In addition, men are hired to pack, load and transport fish products around the market. The market is supplied primarily with processed fish products from various small towns along Ghana’s coast.

Dambai Market

The market in Dambai, the capital of the Oti region, is one of Ghana’s largest markets for inland freshwater fish products. Fish merchants and traders from small towns along Lake Volta transport large quantities of processed freshwater fish to this market. Fish are also sourced from major rivers in the Bono region (Yeji, Buipe, Kajeji and Bui). A large portion of the fish sold in this market is smoke-dried and salted-dried fish. Women entrepreneurs transport the products to markets in Accra’s capital and Kumasi, Ghana’s second-largest city, to serve high-income households and restaurants. ICBT entrepreneurs also transport a large portion of processed fish from this market to markets in neighbouring Togo and Benin.

Denu Market

Denu is a border town located in the Ketu South District of the Volta region of Ghana and is near the Atlantic Ocean. The market is about 10 km from Lomé, the capital of Togo. This significant fish market attracts traders from Togo and Benin. It is a source market for fish and draws fishmongers from all the communities on the south-eastern coast of Ghana and the Volta Lake and Keta Lagoons. Although it is poorly developed, it is one of the biggest fish markets that supplies processed fish products to Togo and Benin. Notably, informal traders dominate most of the trade activities for processed small pelagic fish in this market.

Data collection and analysis

We employed a multi-stage sampling technique through which we assigned each market a proportional allocation based on the trader population provided by the market cooperative. We purposively sampled the leadership of the fish trader cooperatives at the three markets for the focus group interviews. We used a survey to collect data from 223 fish traders on socio-demographics; the infrastructural, institutional and marketing factors associated with trade participation; and the profitability of the trade, for conducting a statistical analysis. These factors included years of experience in fish trade, educational level, access to market information, access to financing, cooperative membership, road condition and language diversity. We also collected data on traders’ cash inflows and outflows and on the price and quantity of fish related to ICBT. The survey questions were pretested (Bolton 1993). The pretest helped addressed the gaps in the questionnaire before the actual fieldwork. Following the pretest, the questions were modified to reflect the informality of the trade. For example, we considered average estimations, and instead of engaging the traders at the border, we opted for market areas, which was more feasible to gain access to ICBT traders. STATA (version 15) was used to conduct the regression analysis on trade participation and profitability.

The focus group interviews were held with five executives of the local market association at each market using a semi-structured interview guide to supplement the quantitative data. The data collection was conducted using two local languages (Twi and Ewe) commonly spoken along the GTB border. The data were collected between July and December in 2018, during the peak season for the small pelagic fish in Ghana. In West Africa, in general, seasonality plays an important role in the trade of these fish in terms of the volume of fish products available and species diversity (Jueseah et al. 2020). The focus group interviews covered the ICBT products, the trade flow routes and the intrinsic and extrinsic social and economic factors that influence this flow. The research team coded the transcribed data manually, thematically grouped the themes and then discussed these themes (Yin 2003). Given that women dominate this trade (Ayilu and Appiah 2020), the survey and semi-structured interviews were both not sex-disaggregated (i.e. the sample comprised only women).

Trade estimation

We calculated the volume and value of the trade transactions for the low-cost processed small pelagic fish by using an approach used to estimate informal trade proposed by Ackello-Ogutu (1996). This approach is used in contexts in which it is challenging to ascertain the accurate trade records of participants. To demonstrate the volume and value of the ICBT, we asked questions ranging from the number of trips a trader embarked on per month, the estimated quantity of baskets of fish purchased for export and the average price of a fish basket (P). The average price per basket of smoke-dried fish during the interview period (July–December 2018) was GHc 130 (US$ 35) in the various markets. We recorded the average volume (Qd) of fish products per basket in kilograms by weighing samples provided by the study participants (average weight = 8 kg) and extrapolated the annual average volume and value using monthly data. We used Microsoft Excel to compute the average daily trade volume (ADTV), annual trade volume (ATV) and annual trade value (AV) using the following Ackello-Ogutu (1996) informal trade approach (Eq. 1):

The calculation was done for individual traders in the sample, N is the number of days in a month a trader exported fish from the market; Qd is the quantity (kg) of fish exported per market day (number of baskets); P refers to the average price of fish per basket and i represents the individual traders.

Model specification

The probit model was used to evaluate the determinants of trade participation. This model was selected rather than the logit model because it accounts for non-constant error variances, such as heteroskedasticity, which results in a more robust statistical regression. The model is robust when analysing individual or firm behaviour in a scenario in which individuals’ desire to optimise the highest satisfaction from their economic decisions, and the observed choice represents a continuous latent variable reflecting the propensity to choose a specific option over others (Mulatu et al. 2018). The dependent variable in the model represents small pelagic fish traders’ decision choices: the decision to engage in ICBT is assigned the value 1 and the decision to not engage in ICBT is assigned 0 (Eq. (2)).

In the equation, ∅ is the standard cumulative normal; β describes the interpretation parameter of the determinants and X represents the following determinants: age, membership in a fish trade cooperative, access to market information, level of education, trader experience, location of trader’s residence, credit availability, household size and perceived road conditions (Table 1).

The determinants of profits of those participating in ICBT were assessed using ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation. This method was considered because the profit value (dependent variable) is continuous. The profit estimation used in the model was selectively limited to only those engaged in ICBT. Therefore, some variables in the participation model were dropped from the profitability model because they were statistical non-significant in determining ICBT participation. Profits earned by those engaged in ICBT were calculated in an MS Excel sheet by using a simple formula, namely, total sales revenue minus total costs.

The OLS model for assessing the determinants of profitability is expressed in Eq. (3).

In which a is a constant term; δ is the interpretation parameter of the determinants and X represents the following determinants: cooperative membership, market information access, trader experience, trader location, credit availability, household size and perceived road conditions. The random error term ε in the equation represents all aspects of the actual population that were not captured in the observed data. The statistical significance of the independent variables in the probit and OLS models were tested at the 10% (p < 0.10), 5% (p < 0.05) and 1% (p < 0.001) levels.

Sample statistics

The summary statistics are presented in Table 1. The age of the fish traders ranged from 20 to 60 years; their mean age was 46 years, and their average mean experience was about 17 years. The means of the dummy (coded 1 and 0) variables in Table 1 represent the fraction of respondents who fall in a specified group. For instance, 0.21 is associated with ‘membership in cooperative’, which indicates that about 21% of the respondents were members of a cooperative. The highest level of educational attainment was high school, and about 48% of the respondents had only basic education. The mean value for ICBT participation suggests that 35% of the surveyed small pelagic fish traders engaged in ICBT and with average annual earnings of approximately US$38,000.

Results

Illuminating trade quantities and mobility dynamics

Volume and value of processed small pelagic fish trade

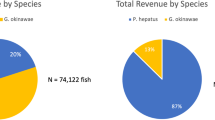

We estimated the valuation of processed fish trade with the aim of showing the volume and value of the trade by considering the price paid by traders who purchased processed small pelagic fish in Ghana. We used the average basket of these processed fish to determine the volume and the average basket price to determine the value. The estimated volumes and values of ICBT in processed pelagic fish products along the GTB borders are presented in Fig. 2. The estimated annual flow of various forms of processed low-cost fish products is approximately 6000 MT (metric tons). This quantity of fish represents a total estimated market value of US$14 million of products transported from the three markets in Ghana through informal channels to neighbouring Togo and Benin. In terms of the distribution by country, 5000 MT of the processed fish (worth US$11.4 million) is transported to Togo, and a total share of 1000 MT (with an estimated market of US$3.5 million) is transported to Benin. It is difficult to calculate reliable estimates of the extent of ICBT in small pelagic fish along the GTB corridor owing to the informality of this trade and estimation limitations. Nevertheless, these estimates illuminate the substantial volume and value of ICBT in processed small pelagic fish products along that trade corridor.

Mobility dynamics of traders

The flow of processed small pelagic fish products broadly represents a dynamic form of trade, and the traders involved employ routes available to reach communities living on both sides of the Ghana–Togo–Benin borders (see Table 2). When transporting large quantities of fish across country borders, traders employ a range of mobility patterns, including rental cargo trucks (used by a group of traders to travel together), rented small vehicles (often used by individual traders) and shared passenger buses with cargo compartments. The most important transnational border checkpoint along GTB is in Aflao town. Here, commuters are subjected to the formal border procedures on both sides of the border. However, most fish traders typically employ minor neighbourhood routes along the town to cross to the other side of the border, which they refused to disclose during the interviews conducted in this study. A limited number of traders also use the main checkpoint; however, they make unofficial payments to border officials to cross the border without submitting to formal customs procedures (Brenton et al. 2011; Golub 2015). Some traders employ the services of unofficial border facilitating agents (intermediaries), with whom they have built a relationship of trust, in order to transport consignments across borders for a fee (Honyenuga 2019). Other main informal routes into and out of Ghana to Togo and Benin are through local border towns on the Ghana side of the border, namely, Nkwanta, Kpassa and Kadjebi. Immigration, custom and military personnel manage these border points. Yet, these three border points remain underdeveloped and are used by neighbouring communities and clans residing on both sides of the borders on a daily basis.

Socio-demographic determinants and marketing dimensions of processed small pelagic fish trade

Socio-demographic characteristics of traders

The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 3. The majority (44.4%) of the women traders were aged between 40 and 50 years. This age range is consistent with that of Nigerian fish marketers observed by Bassey et al. (2014). However, it contrasts with the age proportion engaging in other ICBT merchandise in Africa, who were younger than 40 years (Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), 2007; Little, 2007; Peberdy, 2000). Also, most (81.2%) of the fish traders were married, and another significant cohort consisted of widows (11.2%). In terms of educational attainment, most (65%) had some primary/secondary school education. The remaining cohort (35%) had no formal education, which is consistent with the educational attainment status reported for fish marketers in Nigeria (Bassey et al. 2014). Furthermore, most (47.5%) of the respondents had been in the business for 11 to 20 years, whereas 25.6% had spent 0–10 years in the occupation. Only 0.9% had been in the trade for more than 40 years. About 36.8% of the fish traders had a household size of six and above. The proportion of traders with a household size of four and five were 26.5% and 20.6%, respectively. Only 2.2% had a household size of two persons.

Marketing dimension

Another contextual characteristic commonly associated with processed low-cost SSF product trade worth noting are marketing dimensions, including price determination. We found that 22.7% of the traders who participated in the research considered their operational cost in setting the prices of their products. Also, 22.3% of traders considered seasonality in setting the price, while 21.6% of the traders took into consideration the type of fish species, and 17.1% considered the fish size. Furthermore, 10.5% of other price-setting systems were the market queen’s price determination (i.e. those who act as the leader of a cooperative), 5.0% fish quality (measured by scent and structure, whether broken or not) and 0.7% on fish weight. In addition, trusted relationships and the capacity to make instant cash payments formed the two primary ICBT transactions. For example, the proportion of credit transactions and arrangements were 50%; cash payments were 47% and bank transfers (2.1%) were the least used payment approach.

Socio-demographic determinants of ICBT in small pelagic fish products

All the models were statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the independent variables jointly influence ICBT participation and profitability. The R-squared (pseudo) for the OLS and probit models were, respectively, 27% and 38% (Table 4), which indicates the ability of the independent variables to explain the changes in the dependent variables.

We statistically assessed the various independent variables in the model. The results are presented in Table 4. The Age variable is an important demographic factor related to participation in ICBT, consistent with Ama et al.’s (2014) and Mussa et al.’s (2017) findings. Age shows a negative impact on ICBT participation for small pelagic fish traders. The reference age group was 40–49 years, implying that younger (20–39 years) and old (50 and above) fish traders are less likely to participate in ICBT. Household size was significant at the 1% level (p < 0.001), meaning household size plays an important role in ICBT trade. The negative impact of household size on the profitability of ICBT in small pelagic fish products supports Peberdy’s (2000) finding, which shows that informal traders with large family size along the South Africa and Mozambique border make less profit. However, large household sizes have been proven to provide cheap on- and off-farm labour for other agricultural activities, such as crop farming in developing countries (McNamara and Weiss 2005).

Education was significant at the 1% level (p < 0.001) with a positive coefficient (β = 0.503), which suggests that small pelagic fish traders with some primary education were more likely than their uneducated counterparts to participate in ICBT. As a result, obtaining a primary or secondary level of education increases the likelihood of these actors participating in ICBT by 0.503, consistent with prior research findings (Ama et al. 2014; Jari and Fraser 2009).

Access to market information was significant for ICBT participation at (p < 0.001) with a negative coefficient (β = − 0.720). We specifically attributed this result to the considerable decline in pelagic fish stocks in West Africa. Access to market information is framed to ascertain whether small pelagic fish traders have prior knowledge of small pelagic fish prices and supply availability in the market. Membership in a cooperative is significant at (p < 0.001) and positively influences ICBT participation and profitability, which suggests that small pelagic fish traders who joined a trade cooperative or association were more likely to engage in ICBT and earn a higher profit than those traders who did not. Other studies in Sub-Saharan Africa have also reported similar findings as regards farmers’ market participation (see Gani and Adeoti 2011; Olwande and Mathenge 2010).

For both ICBT participation and profitability, the distance (km) travelled between fish source markets and destination markets was significant at (p < 0.001). Although distance had a positive impact on ICBT participation, it negatively affected profitability, a result consistent with that of Mussema and Dawit (2012) in Ethiopia among red pepper marketers. The availability of good roads positively affected ICBT profitability at (p < 0.001), consistent with the results of other studies in Ethiopia (Gabre-Madhin 2001) and South Africa (Jari and Fraser 2009). The model also showed that the experience level of small pelagic fish traders, as measured by the number of years they were engaged in small pelagic fish trading, positively affected ICBT participation and profitability at (p < 0.001). Lastly, access to credit was significant at the 5% and 1% levels for ICBT participation and profitability. However, contrary to our expectations, credit availability negatively affected both participation and profitability.

Discussion

This section discusses the results in two parts: the first part discusses the trade volumes and values and other factors influencing the trade dynamics, and the second part discusses the determinants of ICBT trade participation and profitability.

Illuminating the small pelagic fish trade

As presented in the “Results”, a substantial amount of processed low-cost small pelagic fish is traded informally along the GTB borders, principally from Ghana’s three biggest fish markets to neighbouring Togo and Benin. The current estimated volumes show that this trade with Togo and Benin remains significant and has more than doubled since the estimates for the 1990s by Tettey and Klousseh (1992). In addition to the difference in the estimation, the reasons for this increase are the population growth and increased fish demand and consumption (Wake and Geleto 2019). Ghana, a prominent fish producer in the region, accounts for more than 448,211 MT of fish production per year during 2017 (Coastal Resources Center 2018). In comparison, Benin and Togo produce about 43,067 MT and 24,132 MT, respectively, in the same period (FAO 2021). As Gordon et al. (2011) noted, Ghana’s small pelagic fish products is transported to neighbouring countries, including Togo and Benin, in order to meet the fish demand by consumers in the region.

In addition, based on the interviews with traders, fish trade along the GTB borders is associated with other social cultural and economic factors. These factors are discussed below in four themes, namely, consumers’ purchasing power, business opportunities, shared heritage and connections and taste and preference for certain fish products.

Consumers’ purchasing power

Fish price remains an important demand-side factor that influences household purchasing behaviour for small pelagic fish products. Low-income households have been found to rely on small fish products as necessities owing to their inability to afford alternative nutritional value products (Dey 2000). In particular, in the global South, dried fish products have been found to contribute to food and nutrition security, health, livelihoods and the social and cultural wellbeing of low-income households (Belton et al. 2022). The demand for these low-cost small pelagic fish products has been growing owing to their relatively low price and their availability in local markets (Ayilu and Appiah 2020). As one seller explained:

You know, life is more challenging in Togo than in Ghana, so the big fish is expensive for them [Togolese], with the small smoke-dried herrings and other small pelagic smoke-dried fish products more affordable (Interview #2, a 54-year-old trader).

This quote suggests that fish consumers prefer certain fish species to others mainly because of the cost. For example, fish sellers often refer to smoked tuna and salmon as ‘big fish’, which is considered more expensive for consumers than small pelagic fish. These low-cost fish products are also easily accessible and affordable. Consumers can purchase these products in small quantities according to their preferences and can preserve these for a considerable period (Aheto et al. 2012; Hasselberg et al. 2020).

Business opportunity

Across different geographical areas, the trade and distribution of small pelagic fish products have increased significantly, supported by a better exchange of information, the commoditisation of fish and an increasing trend in fish demand (FAO 2018; O’Neill and Crona 2017). In West Africa, ICBT in low-cost small pelagic fish products also provides a livelihood and an economic opportunity for women fish traders (Ayilu et al. 2016; Ama et al. 2014; Yusuff 2014; Tall 2005; Baumol 1996), who use it as a means to empower themselves and to provide for their family. This finding is in line with that of others, who similarly found that women fish traders felt empowered (Belton et al. 2022; Béné and Heck, 2005), for example having improved decision-making power in the household and/or in the society at large (Fröcklin et al. 2013). Traders also benefit from exchange rate gains by using Ghanaian currency (cedis) to purchase processed small pelagic fish products in Ghana and sell them in CFA franc in Togo and Benin (Raunet 2016). A trader affirmed:

Since I started purchasing fish from Ghana to Togo for the past 10 years … I have built my house through this business … It is a good business for us, and that is who we are – fish traders (Interview #3, a 48-year-old trader).

Another trader emphasised:

We engage in this trade because through it, we can better care for our families and children ((Interview #1, a 50-year-old trader).

The estimated average annual turnover of women traders in ICBT was $38,000, significantly higher than the minimum wage in Ghana ($74.4), Togo ($63.0) and Benin ($64.0) in 2018 (Countryeconomy.com 2021). The profitability of the trade underscores that the economic benefits associated with the trade serve as significant motivation.

Shared heritage and connection

For many traders in the West African region, national boundaries are virtually meaningless as barriers to the movement of processed small pelagic fish products. Communities sharing similar social cultural practices have been divided by colonial interests and remain divided to date (Howard 2007). As noted by Howard (2007), border markets in most West African countries predate the colonial period and represent international gateways in contemporary trade. For small pelagic fish traders in West Africa, the existing official border routes are a colonial legacy; as such, they cannot constitute a moral barrier to their identity and livelihood (Raunet 2016). Moreover, the spatial similarities and economic patterns in West Africa, including the fluidity of territorial borders (Walther 2012), constitute an enabling condition for low-cost fish trade. In addition, they rely on improvised tactics, such as smuggling and bribing border officials, to cross the border (Mussa et al. 2017; Bensassi and Jarreau 2019). Most of these activities evade formal government regulation and taxation; however, they provide the population with economic opportunities, livelihoods and nutritional needs (Ackello-Ogutu and Echessah 1997; Lesser and Leeman 2009; Titeca 2012).

Taste and preference

Lastly, the processed small pelagic fish trade is influenced by a taste and preference in Togo and Benin for Ghana’s processed small pelagic fish products. Ghanaian processed fish has become popular because of the traditional processing method used (Bomfeh et al. 2019). Women process these fish in local coastal fishing communities using traditional processing methods, such as smoking with Chorkor smoking kilns, sun-drying and salting, to increase the products’ shelf life, and to add value (Akintola and Fakoya 2017; Stolyhwo and Sikorski 2005). Although most of these processed fish products are destined for local consumption in domestic markets, consumers in Togo and Benin prefer Ghanaian smoked-fish products. This processing technique has been adopted for fish processing in these countries, too, yet consumers regard Ghanaian smoked fish to be of superior quality. For example, the entire anchovy and herring, that is, with the head, are smoked without any considerable processing, such as scaling, and are thus very nutritious for consumers. One trader reported:

This processed fish is preferred in Togo and Benin because of the taste; it is delicious when blended into soups (Interview #2, a 48-year-old trader).

Socio-demographic determinants of ICBT participation and profitability

Age, household size and education are key factors in business decision-making in the small pelagic fish trade (Kuépié et al. 2016). Age is related to knowledge and experience, which are crucial success determinants for informal sector businesses (Fadahunsi and Rosa 2002; Casson 2005). The results show that young inexperienced fish traders are less likely than more experienced fish traders to engage in ICBT. This finding is in line with those of Ama et al. (2014), who showed that the number of years spent engaging in ICBT in Botswana is a significant determinant of profit and participation. More experienced traders have accumulated adequate knowledge and understanding of profit-enhancing trading techniques over the years. Similarly, as Fadahunsi and Rosa (2002) observed, inexperienced traders are more likely to be risk-averse and thus less willing to accept the risk of product confiscation connected with ICBT or dealing with border agents. In addition, young traders in the current study indicated that they lacked a network with border authorities and unofficial intermediaries for assuring accessible transit at the border, unlike older traders with better networks owing to their prolonged trading experience.

Education level also plays an essential role in traders’ ability to conduct basic business arithmetic. Basic numerical literacy helps traders to easily convert currency, which is critical for ICBT in West Africa. In particular, in West Africa, which does not have a common currency, most currency exchanges in the informal economy are through the illegal (black) market (Fadahunsi and Rosa 2002). The finding suggests that participation in informal cross-border trading involves a fundamental understanding of currency conversion.

Other factors affecting ICBT participation and profitability include (1) market information, (2) membership in an unofficial trade cooperative, (3) distance and road difficulties and (4) credit availability. Firstly, with regard to market information, recent years have seen a general decline of small pelagic fish catches in West Africa (Atta‐Mills et al. 2004). This affects the available volumes of processed fish at fish markets and has inflated prices (Failler and Binet 2011). We theorise that, as a result, when traders receive market information on product shortages and frequent upward price adjustments for a basket of fish at source markets in Ghana, they are more likely to be discouraged from engaging in ICBT.

Secondly, membership in an unofficial trade cooperative provides the needed network for small pelagic fish traders to promote welfare and confidence among traders, allowing them to take risks and explore new prospects (Ayilu and Appiah 2020; Fadahunsi and Rosa 2002). This finding is consistent with the works on Meagher (2006) in Nigeria which shows that social networks provide ICBT traders with a platform to share creative improvisation ideas for effectively navigating border control checkpoints. Furthermore, as observed in Ghana by Britwum (2009), older fish traders share knowledge and pass their experience by grooming their daughters or trusted relatives to continue the trading business. This finding implies that substantial peer mentoring is required to improve the participation of younger traders in the ICBT, which can be accomplished partly through trade cooperatives. Interestingly, the older, more seasoned traders who participated in the study were willing to mentor newcomers and encourage them to embrace ICBT as a viable alternative livelihood occupation.

Thirdly, infrastructural and logistic challenges, such as distance and road conditions, affect profitability and increase the stress and risk for ICBT traders. Longer distances combined with a poor road system directly affect traders’ profits through transportation costs, which account for a considerable proportion of the revenue from cross-border trade transactions (Jari and Fraser 2009; Mussema and Dawit 2012).

Finally, access to financial credit has a negative effect on ICBT participation and profits. We attribute this to the fact that most of the traders in the informal sectors rely on unregulated financial means to gain access to credit, such as borrowing from local moneylenders at high-interest rates, which can have a negative impact on their profits and lead to business collapse. Thus, financial problems remain a significant determinant of engaging in ICBT (Webb et al. 2013).

Conclusion

Research on the social, economic, historical and cultural dimensions of the processed small pelagic fish trade in West Africa remains limited, despite its contribution to livelihood and food security. In this study, we focused on the informal cross-border fish trade between Ghana and neighbouring Togo and Benin. The study illuminates the potential of ICBT in processed small pelagic fish, in terms of trade volume and value, the trade flow dynamics and the various socio-demographic determinants of participation and profitability. Owing to the increasing importance of these processed products and the volume transported through ICBT channels, these channels have become a significant mode of distributing fish products from Ghana to meet consumption and consumers’ needs in Benin and Togo. Beyond food and nutrition security, ICBT has also become a business opportunity for women in West Africa’s fish value chain, yet there are sociodemographic, infrastructural and logistic challenges.

Despite the research limitations in terms of sample size, the trade volume and the value estimations because of the difficulties related to examining this type of informal trade, our findings illuminate the untapped potential of ICBT in processed small pelagic fish in West Africa. To better optimise the economic potential and value of these forms of fish trade, we strongly recommend the inclusion of ICBT on the agenda at the national and the regional levels of trade policy discussion. There is untapped potential that could be utilised effectively to address the issues of unemployment, poverty and food security in the West African region. Moreover, future research is needed with a more expanded sample size to accentuate the livelihood and economic potential and contributions of ICBT in processed small pelagic fish in this region.

References

Ackello-Ogutu, C. 1996. Methodologies for estimating informal crossborder trade in Eastern and Southern Africa: Kenya/Uganda border, Tanzania and its neighbors, Malawi and its neighbours Mozambique and its neighbours. Retrieved from: http://41.204.161.209/bitstream/handle/11295/49521/DOC4513.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 24 Sept 2021.

Ackello-Ogutu, C., and P Echessah. (1997). Unrecorded cross-border trade between Kenya and Uganda Implications for Food Security. SD Publication Series Office of Sustainable Development Bureau for Africa. Technical Paper No. 59

Aheto, D.W., N.K. Asare, B. Quaynor, E.Y. Tenkorang, C. Asare, and I. Okyere. 2012. Profitability of small-scale fisheries in Elmina, Ghana. Sustainability 4 (11): 2785–2794.

Akintola, S.L., and K.A. Fakoya. 2017. Small-scale fisheries in the context of traditional post-harvest practice and the quest for food and nutritional security in Nigeria. Agriculture & Food Security 6 (1): 1–17.

Akinboade, O.A. 2005. A review of women, poverty and informal trade issues in East and Southern Africa. International Social Science Journal 57 (184): 255–275.

Ama, N.O., K.T. Mangadi, F.N. Okurut, and H.A. Ama. 2014. Exploring the challenges facing women entrepreneurs in informal cross-border trade in Botswana. Gender in Management 29 (8): 505-522. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-02-2014-0018

Appiah, S., T.O. Antwi-Asare, F.K. Agyire-Tettey, E. Abbey, J.K. Kuwornu, S. Cole, and S.K. Chimatiro. 2021. Livelihood vulnerabilities among women in small-scale fisheries in Ghana. European Journal of Development Research 33 (6): 1596–624. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00307-7

Atta‐Mills, J., J. Alder, and U.R. Sumaila. 2004. The decline of a regional fishing nation: the case of Ghana and West Africa. In Natural Resources Forum (Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 13–21). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Ayilu, R. K., and S. Appiah. 2020. Fish traders and processors network: Enhancing trade and market access for small-scale fisheries in the West Central Gulf of Guinea. In Securing sustainable small-scale fisheries: Showcasing applied practices in value chains, post-harvest operations and trade, 652, Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, 71.

Ayilu, R. K., T. O. Antwi-Asare, P. Anoh, A. Tall, N. Aboya, S. Chimatiro, and S. Dedi. 2016. Informal artisanal fish trade in West Africa: Improving cross-border trade, 2016–2037. Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish. Program Brief.

Baumol, W.J. 1996. Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Business Venturing 11 (1): 3–22.

Bassey, N.E., O.E. Uwemedimo, I.U. Uwem, and N.E. Eteyen. 2014. Analysis of the determinants of fresh fish marketing and profitability among captured fish traders in South-South Nigeria: The case of Akwa Ibom State. British Journal of Economics Management & Trade 5 (1): 35–45.

Belton, B., D.S. Johnson, E. Thrift, J. Olsen, M.A.R. Hossain, and S.H. Thilsted. 2022. Dried fish at the intersection of food science, economy, and culture: A global survey. Fish and Fisheries 23 (4): 941–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12664

Belhabib, D., A. Mendy, Y. Subah, N.T Broh, A.S. Jueseah, N. Nipey, ... and D. Pauly. 2016. Fisheries catch under-reporting in The Gambia, Liberia and Namibia and the three large marine ecosystems which they represent. Environmental Development 17: 157–174.

Béné, C., and S. Heck. 2005. Fish and food security in Africa. NAGA, Worldfish Center Quarterly, Vol. 28. http://hdl.handle.net/1834/25699. Accessed Jan 2022.

Béné, C., and R.M. Friend. 2011. Poverty in small-scale fisheries: Old issue, new analysis. Progress in Development Studies 11 (2): 119–144.

Bensassi, S., and J. Jarreau. 2019. Price discrimination in bribe payments: Evidence from informal cross-border trade in West Africa. World Development 122: 462–480.

Bolton, R.N. 1993. Pretesting questionnaires: Content analyses of respondents’ concurrent verbal protocols. Marketing Science 12 (3): 280–303.

Bomfeh, Kennedy, Liesbeth Jacxsens, Wisdom Kofi Amoa-Awua, Isabella Tandoh, Emmanuel Ohene Afoakwa, Esther Garrido Gamarro, Yvette Diei Ouadi, and Bruno De Meulenaer. 2019. Reducing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contamination in smoked fish in the Global South: A case study of an improved kiln in Ghana. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 99 (12): 5417–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.9802

Brenton, P., Bucekuderhwa, C. B., Hossein, C., Nagaki, S., & Ntagoma, J. B. 2011. Risky business: Poor women cross-border traders in the great lakes region of Africa. Africa Trade Policy Note, 11. Retrieved from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/742571468007855952/pdf/601120BRI0Afri11public10BOX358310B0.pdf. Accessed 23 Aug 2021.

Britwum, A. O. (2009). The gendered dynamics of production relations in Ghanaian coastal fishing. Feminist Africa.

Casson, M. 2005. Entrepreneurship and the theory of the firm. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 58 (2): 327–348.

Chan, C.Y., N. Tran, S. Pethiyagoda, C.C. Crissman, T.B. Sulser, and M.J. Phillips. 2019. Prospects and challenges of fish for food security in Africa. Global Food Security 20: 17–25.

Chimatiro, S., J. Linton, B. Omitoyin, and J. de Bruyn. 2017. Informal cross-border fish trade: invisible, fragile and important. WorldFish Center, Policy Brief No. 2

Coastal Resources Center. 2018. Republic of Ghana fisheries and Aquaculture sector development plan. Retrieved from: http://rhody.crc.uri.edu/gfa/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2018/04/Ghana-Fisheries-and-Aquaculture-Sector-Development-Plan-2011-2016.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2021.

Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). 2007. Report of the regional consultative meeting on the implementation of the COMESA simplified trade regime, August 2007, CS/TCM/STR/I/2.

Countryeconomy.com. 2021. Monthly minimum wage. Retrieved from: https://countryeconomy.com/countries/compare/togo/benin. Accessed 26 June 2021.

Dey, M.M. 2000. Analysis of demand for fish in Bangladesh. Aquaculture Economics & Management 4 (1–2): 63–81.

Fadahunsi, A., and P. Rosa. 2002. Entrepreneurship and illegality: Insights from the Nigerian cross-border trade. Journal of Business Venturing 17 (5): 397–429.

Failler, P., and T. Binet. 2011. A critical review of the European Union West African fisheries agreements. Oceans the new frontier. AFD IDDRI TERI 166–170. Accessed 9 Nov 2021.

Faleye, O.A. 2014. Impact of informal cross border trade on poverty alleviation in Nigeria: Kotangowa Market [Lagos] in perspective. Crossing the Border: International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2 (1): 13–22.

FAO. 2017. Towards gender-equitable small-scale fisheries governance and development: a handbook. Biswas N, editor. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 174 p. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7419e.pdf. Accessed 3 June 2022.

FAO. 2018. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Rome. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/state-of-fisheries-aquaculture. Accessed 3 Jul 2021.

FAO. 2021. Fishery and aquaculture country profiles – the Republic of Benin. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/fishery/facp/BEN/en#:~:text=Aquaculture%20employment%20was%20reported%20at,sea%20of%20200%20nautical%20miles. Accessed 5 Aug 2021.

Fröcklin, S., M. de la Torre-Castro, L. Lindström, et al. 2013. Fish traders as key actors in fisheries: Gender and adaptive management. Ambio 42: 951–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-013-0451-1

Gabre-Madhin, E.Z. 2001. Market institutions, transaction costs, and social capital in the Ethiopian grain market, vol. 124. Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

Gani, B.S., and A.I. Adeoti. 2011. Analysis of market participation and rural poverty among farmers in northern part of Taraba State Nigeria. Journal of Economics 2 (1): 23–36.

Golub, S. 2015. Informal cross-border trade and smuggling in Africa. Edward Elgar Publishing In Handbook on trade and development.

Gordon, A., A. Pulis and E. Owusu-Adjei. 2011. Smoked marine fish from Western Region, Ghana: a value chain assessment. The WorldFish Center. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1834/25248. Accessed 9 Oct 2021.

Gorodnichenko, Y., and L. Tesar. 2005. A re-examination of the border effect (No. w11706). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w11706/w11706.pdf. Accessed 23 May 2021.

Harper S., and D. Kleiber. 2019. Illuminating gender dimensions of hidden harvests. SPC Women in Fisheries Information Bulletin. 2019 Sep; Issue 30.

Harper, S., M. Adshade, V.W. Lam, D. Pauly, and U.R. Sumaila. 2020. Valuing invisible catches: Estimating the global contribution by women to small-scale marine capture fisheries production. PLoS One 15 (3): e0228912.

Harper, S., D. Zeller, M. Hauzer, D. Pauly, and U.R. Sumaila. 2013. Women and fisheries: Contribution to food security and local economies. Marine Policy 39: 56–63.

Hasselberg, A. E., I. Aakre, J. Scholtens, R. Overå, J. Kolding, M.S. Bank, ... and M. Kjellevold. 2020. Fish for food and nutrition security in Ghana: challenges and opportunities. Global Food Security 26: 100380.

Howard, A. M. 2007. Mande Kola traders of Nortwestern Sierra Leone, late 1700s to 1930. Mande Studies 9 (2007): 83–102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44080896

Honyenuga, B.Q. 2019. Informal Cross Border Women Entrepreneurship (ICBWE) in West Africa: Opportunities and Challenges. In: Ramadani, V., Dana, LP., Ratten, V., Bexheti, A. (eds) Informal Ethnic Entrepreneurship. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99064-4_7

International Collective in Support of Fishworkers. 2002. Report of the study on the problems and prospects of artisanal fish trade in Africa. Chennai, India. 86 pp. Accessed: http://aquaticcommons.org/256/1/rep_WAfrica_artisanal_fishtrade.pdf

Jari, B., and G.C.C. Fraser. 2009. An analysis of institutional and technical factors influencing agricultural marketing amongst smallholder farmers in the Kat River Valley, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. African Journal of Agricultural Research 4 (11): 1129–1137.

Jueseah, A.S., O. Knutsson, D.M. Kristofersson, and T. Tómasson. 2020. Seasonal flows of economic benefits in small-scale fisheries in Liberia: A value chain analysis. Marine Policy 119: 104042.

Kelleher, K., L. Westlund, E. Hoshino, D. Mills, R. Willmann, G. de Graaf and R. Brummett. 2012. Hidden harvest: the global contribution of capture fisheries. World bank; WorldFish. Retrieved from: https://digitalarchive.worldfishcenter.org/handle/20.500.12348/992. Accessed 10 Dec 2021.

Kuépié, M., M. Tenikue, and O.J. Walther. 2016. Social networks and small business performance in West African border regions. Oxford Development Studies 44 (2): 202–219.

Lawless, S., P.J. Cohen, S. Mangubhai, D. Kleiber, and T.H. Morrison. 2021. Gender equality is diluted in commitments made to small-scale fisheries. World Development 140: 105348.

Lawless, S., P.J. Cohen, C. McDougall, G. Orirana, F. Siota, and K. Doyle. 2019. Gender norms and relations: Implications for agency in coastal livelihoods. Maritime Studies 18 (3): 347–358.

Lesser, C., and E.M. Leeman. 2009. Informal cross-border trade and trade facilitation reform in Sub-Saharan Africa. OECD Trade Policy Working Papers, No.86. OECD Publishing.

Little, P.D. 2007. Unofficial Cross-Border Trade in Eastern Africa Paper presented at the FAO Workshop on Staple Food Trade and Market Policy Options for Promoting Development in Eastern and Southern Africa. Rome: FAO.

Mancha-Cisneros, M. D. M., X. Basurto, N. Franz and S. Funge-Smith. 2019. Illuminating hidden harvests: the global and local contributions and impacts of small-scale fisheries to sustainable development. Retrieved from: https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/10515/Mancha-Cisneros%20et%20al_10June2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Accessed 12 Apr 2022.

Marquette, C.M., K.A. Koranteng, R. Overå, and E.B.D. Aryeetey. 2002. Small-scale fisheries, population dynamics, and resource use in Africa: the case of Moree, Ghana. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 31 (4): 324–336.

McNamara, K.T., and C. Weiss. 2005. Farm household income and on-and off-farm diversification. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 37 (1): 37–48.

Meagher, K. 2006. Social capital, social liabilities, and political capital: Social networks and informal manufacturing in Nigeria. African Affairs 105 (421): 553–582.

Mills, D. J., L. Westlund, G. de Graaf, Y. Kura, R. Willman, and K. Kelleher. 2011. “Under-reported and undervalued: small-scale fisheries in the developing world.” In Small-scale fisheries management: Frameworks and approaches for the developing world. London, UK: CAB international. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845936075.0001

Mulatu, D.W., P.R. van Oel, V. Odongo, and A. van der Veen. 2018. Fishing community preferences and willingness to pay for alternative developments of ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) for Lake Naivasha, Kenya. Lakes & Reservoirs: Research & Management 23 (3): 190–203.

Mussa, H., E. Kaunda, S. Chimatiro, K. Kakwasha, L. Banda, B. Nankwenya, and J. Nyengere. 2017. Assessment of informal cross-border fish trade in the Southern Africa Region: A case of Malawi and Zambia. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology B 7 (5): 358–366.

Mussema, M., and A. Dawit. 2012. Red pepper marketing in Siltie and Alaba in SNNPRS of Ethiopia: Factors affecting households’ marketed pepper. International Research Journal of Agricultural Science and Soil Science 2 (6): 261–266.

Neiland, A.E. 2006. Contribution of fish trade to development, livelihoods and food security in West Africa: Key issues for future policy debate Portsmouth. UK: IDDRA Ltd.

Nshimbi, C., and I. Moyo. 2017. Migration, cross-border trade and development in Africa. Palgrave Studies of Sustainable Business in Africa). Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nyiawung, R.A., R.K. Ayilu, N.N. Suh, N.N. Ngwang, F. Varnie, and P.A. Loring. 2022. COVID-19 and small-scale fisheries in Africa: Impacts on livelihoods and the fish value chain in Cameroon and Liberia. Marine Policy 141: 105104.

O’Neill, E.D., and B. Crona. 2017. Assistance networks in seafood trade–a means to assess benefit distribution in small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy 78: 196–205.

Olwande, J., and M. K Mathenge. 2010. Market participation among poor rural households in Kenya. Egerton University and World Agroforestry Center Tegemeo Institute of Agricultural Policy and Development.

Peberdy, S.A. 2000. Border crossings: Small entrepreneurs and cross-border trade between South Africa and Mozambique. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 91 (4): 361–378.

Raunet, N. 2016. Chiefs, Migrants and the State: Mobility in the Ghana–Togo Borderlands. International Migration Institute (IMI). Working Paper Series. 128. Retrieved from: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:14df751e-cf4d-49c8-8087-9e674bb1bf3a. Accessed 23 Aug 2022.

Sowman, M., J. Sunde, S. Raemaekers, and O. Schultz. 2014. Fishing for equality: Policy for poverty alleviation for South Africa’s small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy 46: 31–42.

Stołyhwo, A., and Z. Sikorski. 2005. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in smoked fish – a critical review. Food Chemistry 91 (2): 303–311.

Tall, A. 2005. Obstacles to the development of small-scale fish trade in West Africa. INFOPECHE, Abidjan, p. 18. Last accessed August 16, 2020. Accessed: https://www.oceandocs.org/bitstream/handle/1834/745/Infopeche.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Teh, L.C., and U.R. Sumaila. 2013. Contribution of marine fisheries to worldwide employment. Fish and Fisheries 14 (1): 77–88.

Tettey, E.O., and K. Klousseh. 1992. Transport of cured fish from Ghana to Cotonou Trade formalities and constrain. Abdiyah Regional Programme to improve post-harvest utilisation of artisanal fish catch in West African. Bonga Fish Tech. Report Series 1: 92–97.

Thorpe, A., N. Pouw, A. Baio, R. Sandi, E.T. Ndomahina, and T. Lebbie. 2014. Fishing Na everybody business: Women’s work and gender relations in Sierra Leone’s fisheries. Feminist Economics 20 (3): 53–77.

Titeca, K. 2012. Tycoons and contraband: Informal cross-border trade in West Nile, north-western Uganda. Journal of Eastern African Studies 6 (1): 47–63.

Titeca, K., & T. De Herdt. 2010. Regulation, cross-border trade and practical norms in West Nile, north-western Uganda. Africa 80 (4): 573-594. https://doi.org/10.3366/afr.2010.0403.

Uduji, J.I., and E.N. Okolo-Obasi. 2020. Does corporate social responsibility (CSR) impact on development of women in small-scale fisheries of sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence from coastal communities of Niger Delta in Nigeria. Marine policy 118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.10.036

Wake, A.A., and T.C. Geleto. 2019. Socio-economic importance of Fish production and consumption status in Ethiopia: A review. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 7 (4): 206–211.

Walther, O. 2012. Traders, agricultural entrepreneurs and the development of cross-border regions in West Africa. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 24 (3–4): 123–141.

Webb, J.W., G.D. Bruton, L. Tihanyi, and R.D. Ireland. 2013. Research on Entrepreneurship in the Informal Economy: Framing a Research Agenda. Journal of Business Venturing 28 (5): 598–614.

Yin, R. K. 2003. Designing case studies. Qualitative Research Methods, 359–386. London: SAGE Publication.

Yusuff, S.O. 2014. Gender dimensions of informal cross border trade in West-African sub-region (ECOWAS) borders. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences 29: 19–33.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers and the guest editor of the special issue whose comments have tremendously improved the quality of paper. We would like to also acknowledge support from the Journal Article Award as part of the 8th Global Conference on Gender in Aquaculture and Fisheries (GAF8), presented by Gender in Aquaculture Section of the Asian Fisheries Society with the CGIAR research program on Fish Agri-Food Systems (FISH) led by WorldFish and the CGIAR gender Platform. We would want to recognize a special friend and colleague, the late Dr. Isaac Ankamah-Yeboah for his initial mentoring during the WorldFish Zambia Office writeshop.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions These study design and data collection were undertaken as part of the European Union-funded Fish Trade Programme in Africa implemented through the WorldFish, Lusaka Zambia office. No funding was allocated for the development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RKA conceptualised the research, data analysis and drafted the first version of the manuscript. RAN contributed in revising the manuscript. All the authors contributed in literature review, analysis, discussion and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and by no means those of the European Union or WorldFish.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayilu, R.K., Nyiawung, R.A. Illuminating informal cross-border trade in processed small pelagic fish in West Africa. Maritime Studies 21, 519–532 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-022-00284-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-022-00284-z