Abstract

Background

Neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) is a leading cause of blind registrations in the developed world. Standard therapy includes the use of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) drugs, and whilst the clinical efficacy is well established, there is variability in the clinical effect of visual outcome. The purpose of this systematic review is to identify whether there is evidence for the influence of demographic and clinical factors on the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy in patients with nAMD, in settings comparable to the National Health Service (NHS).

Methods

This systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews. Electronic databases Medline, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library were searched for studies dated from 2005 onwards. Studies were appraised using the Newcastle–Ottawa Score, and a narrative synthesis was used.

Eligibility Criteria

Population: Patients with nAMD being treated with anti-VEGF therapy. Comparator: Presence or absence of potential predictive demographic and clinical factors. Settings: Comparable settings to NHS hospitals. Outcomes: Predicting demographic and clinical factors. Study designs: Randomised controlled trials, prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies and case series dated from 2005.

Results

Thirty papers were identified in this review. The evidence suggests that the number of anti-VEGF injections that patients receive, age and lesion size at baseline are factors that influence how effective anti-VEGF therapy is in the short and long term. There was also evidence that suggested that baseline visual acuity influenced the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy at longer time points of more than 2 years. Due to a lack of standardised statistical reporting among the included studies, it was not possible to undertake a meaningful statistical synthesis or meta-analysis.

Conclusions

This review has demonstrated that there is some evidence of clinical and demographic factors that affect the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy and hence variation in visual acuity (VA) outcome. However, this review was unable to identify as wide a range of factors as was hoped. The findings of this review are important because some of the factors, such as VA and lesion size at diagnosis and the number of injections, are potentially modifiable through improvements in early diagnosis and service provision. Future work also needs to focus on the importance of this variation, such as the effect on patients’ quality of life, and how variation can be minimised.

Systematic Review Registration

This review has been registered with PROSPERO (Registration number CRD42018094191).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The burden of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) is growing with an ageing population, and is one of the leading causes of blindness in the developed world. |

While anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) prevents sight loss in some patients, some patients still lose their sight, and the reasons for this are largely unknown. |

This study asked whether from the current evidence, demographic and clinical factors that influence the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy in patients with nAMD. |

What was learned from this study? |

The study found that age, baseline visual acuity, lesion size and number of injections influenced the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy. |

However, it did not find any other significant factors from the literature, and was not able to undertake a statistically meaningful assessment of the findings. |

This study has revealed that more information needs to be gathered on factors that could influence the success of anti-VEGF therapy, and that perhaps there needs to be more standardisation of how findings in nAMD studies are reported, to enable statistical analysis. |

Introduction

It is well established that nAMD is one of the leading causes of blind registrations in the developed world [1,2,3]. With an ageing population in developed countries, this will lead to an increase in the burden of visual disability due to nAMD [1, 2, 4].

Untreated nAMD leads to severe visual loss in most patients over a 2-year period [5]. Anti-VEGF treatment given regularly stabilises vision in around 95% of those with nAMD [5,6,7]. It has been shown that over a 4-year period of treatment with ranibizumab, the cumulative incidence of new blind registrations was 5.1% in year 1, 8.6% in year 2, 12% in year 3 and 15.6% in year 4, demonstrating significant reductions in blind registrations once treatment was initiated [8]. However, there is variability in both individual and patient group clinical response and consequently visual outcomes [9]. Real-world clinical effectiveness has broadly not managed to reproduce this efficacy. One real-world study demonstrates slow visual loss from baseline over 1–2 years [10]. The pivotal phase III clinical trials of anti-VEGF agents demonstrate this individual variability in outcome amongst their sample of participants [5, 6]. This trial found that of 140 patients receiving 0.5 mg ranibizumab, 96.4% had lost fewer than 15 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letters and visual acuity improved by 15 letters or more in 40.3% at 12 months. It has been questioned whether there are demographic and clinical factors that could affect this variation in clinical response.

It is important to understand why this variation occurs, and to understand whether any causes of this variation are potentially modifiable. The Lord Carter Report [11] recognised the importance of understanding variation in healthcare provision, when it found that variation due to modifiable factors is worth £5 billion in terms of efficiency, and accounts for nearly 10% of the money spent by acute trusts. In addition, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for age-related macular degeneration [12] recommend further research into how service design affects long-term effectiveness of treatment.

The aim of this review is to identify whether there is evidence, in patients with nAMD being treated with anti-VEGF therapy that demographic and clinical factors contribute to the variation in the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy for nAMD.

Methods

The methodology of this systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol for this review is registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42018094191). It can be found at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. As this was a review of published literature, there was no requirement to seek ethical approval. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

The electronic databases Medline, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library were searched for relevant published literature. The search strategy was designed with the assistance of a specialist librarian. The search took place between January and March 2018. Information on studies in progress, unpublished research or research reported in the grey literature were sought by searching a range of relevant databases including the National Research Register, Current Controlled Clinical Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Standard Randomised Clinical Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry. Bibliographies of retrieved articles were also examined. For an example of the search strategy used please refer to Appendix 1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

Eligibility Criteria

Table 1 gives the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the search. For the purposes of this review, the term ‘demographic factors’ refers to individual patient characteristics such as age and ethnicity. The term ‘clinical factors’ refers to clinical features of the disease at diagnosis, such as lesion size, and features of patients’ treatment in nAMD clinic, such as number of injections. Similar definitions of demographic and clinical factors were used in a large retrospective study of intra-centre variation in the UK [13]. The present review focused on settings comparable to UK hospitals for the sake of comparability, as it would be more difficult to compare treatment patterns and outcomes with those in some developing countries, for example, as treatment for nAMD may not be as widely established or available at all. Hospitals that were comparable to UK hospitals were defined as hospitals in developed countries that were able to provide treatment to patients with nAMD. It was decided to only include papers from 2005 onwards, because anti-VEGF treatment was not widely used to treat nAMD until then.

Study Selection

The citations identified by the search strategy were assessed for inclusion in two stages and by two independent reviewers. In stage 1, two reviewers (CG, RG) independently screened all relevant titles and abstracts identified via electronic searching to identify potentially relevant studies for inclusion in the review. Stage 2 focused on the independent assessment of the full-text copies of those studies identified by the two reviewers (CG, RG) in phase 1. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion at each stage.

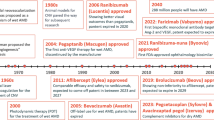

Of the 4835 citations identified from the search, 2604 titles and abstracts were screened (stage 1), and 28 were included in stage 2 screening. Three additional papers were identified from hand searching, and one paper was unavailable. Overall, 30 papers were included in this review, comprising three prospective cohort studies, 19 retrospective cohort studies and eight retrospective studies of trial data. The included studies represented > 24,500 patients in total. The characteristics and outcomes assessed in each study are presented in Tables S1 and S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material. Overall, the included studies were observational cohort studies, case series or retrospective studies. Figure 1 gives a flow diagram of the study selection process.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. This was done at the study level. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale is a widely used tool for assessing the quality of non-randomised observational studies. A judgement as to the possible risk of bias in each of the six domains was made from the extracted information, rated as ‘high risk’ or ‘low risk’. Where there was insufficient detail reported in the study, the risk of bias was recorded as ‘unclear’. The quality of the individual studies was assessed by one reviewer (CG), and a sample of quality assessments independently was checked by a second reviewer (CH). Disagreements were resolved through consensus.

Overall, the methodological quality of the included studies was very good. For all the studies, quality was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, and studies were rated as being at low risk of bias. All studies scored at least 5 out of a possible 7 stars, with most of the studies achieving 6 stars. One study only scored 5 stars because its follow-up procedures were unclear. All the other studies scored 6 stars, and were not awarded 7 stars only because they did not have a comparison arm. The high quality of the studies included in this review informed the narrative synthesis of the findings.

Results

Demographic Factors

Gender

Ten studies explored the impact of gender as an influencing factor on the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy [10, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] (please see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material), nine of which found it to be a non-statistically significant influence on visual outcome. SE refers to standard error, OR to odds ratio, and CI to confidence interval. The only study that found gender to be a statistically significant factor in influencing visual outcomes was a 2014 study of 210 eyes from 192 patients [19]. The authors found that the mean change in reference central retinal thickness (RCRT) at 6 months after the last injection in men vs. women was −6.47 (SE ± 7.18, p = 0.05), highlighting that men had a greater reduction in RCRT than women. This was the only paper that looked at the effect of gender on central retinal thickness (CRT) rather than on visual score, which may explain why it was the only study that found it to be a significant factor.

Age

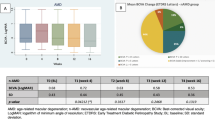

Fourteen studies explored the influence of age on the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy [5, 14,15,16,17,18,19, 21,22,23,24,25] (please see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material), eight of which reported age to be a statistically significant predictor of visual outcomes. From these studies, the overall effect of age was that the higher the age at baseline, the lower the visual outcome at time points of 1, 2 and 3 years. As it was not statistically possible to combine the data from the studies to give a statistical effect size with confidence intervals, the studies with some of the largest sample sizes are highlighted in the text below. Figure 2 demonstrates this distribution of studies with their sample sizes.

For example, one of the studies with a sample of 1185 patients [25] found significantly higher odds of gaining ≥ 3 letters at 12 months for younger patients (aged 50–69 years) than for older patients (> 70) (p = 0.008). In another study [22], age was found to be a significant predictor of VA change at the year 2 time point, but not at the year 1 time point (Y1: −0.106, 95% CI −0.2 to 0.052; Y2: −0.1, 95% CI −0.3 to −0.0. Age at first injection was also found to be a non-statistically significant predictor of visual outcomes over 4 years [15] (year 2: p = 0.126; year 3: p = 0.262; and year 4: p = 0.090 time points).

Higher age at diagnosis may lead to worse visual outcomes because older patients are more likely to have a larger extent of damage and may have developed resistance to treatment agents. However, this could be further hampered by the fact that they are less likely to still be able to drive and may therefore have difficulty getting to clinic often enough if they are relying on hospital transport, relatives or public transport to get to clinic.

Other Demographic Factors

One paper also looked at aspirin use, warfarin use, diabetes, family history of AMD, glaucoma, clopidogrel use, smoking history and use of statins [15]. However, none of these factors was found to be statistically significant. None of the included studies looked at the effect of ethnicity.

Clinical Factors

Baseline VA or BCVA

Of the 21 studies that explored the impact of baseline VA or best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) on the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy [5, 10, 13, 14, 17,18,19,20,21,22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] (please see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material), 18 reported it to be a statistically significant predictor of visual acuity. The overall effect of baseline VA on visual outcome was that the lower the baseline VA, the lower the visual outcome at time points of 1 year and later. It was not statistically possible to combine the data from studies to calculate a statistical effect size and confidence intervals; however, Fig. 3 shows the distribution and study size of the studies with a statistically significant finding for baseline VA. The study with one of the largest samples [22] of 2227 patients found that baseline VA was a statistically significant predictor of VA at both 1 and 2 years (Y1: −0.21 95% CI −0.35 to −0.21; Y2: −0.39, 95% CI −0.46 to −0.32).

Lesion Size

Ten studies explored the impact of baseline lesion size on the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy [5, 6, 14, 15, 17, 20, 21, 23, 25, 28] (please see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material), and seven of these were statistically significant. The overall effect of lesion size on VA was that the smaller the lesion size at baseline, the better the VA at time points longer than 12 months. It was not statistically possible to combine the data from studies to calculate a statistical effect size and confidence intervals; however, Fig. 4 shows the distribution and size of the studies with a statistically significant finding for lesion size. The studies with some of the largest sample sizes are highlighted in the text below.

One study reported that the odds of BCVA ≥ 70 with a total lesion size < 4 disc area (DA) were three times the odds of those with a lesion size ≥ 4 DA at 12 months [14] (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.25–7.40). Ying et al. [25] found the same odds that patients with smaller baseline lesion areas would gain ≥ 3 letters at 12 months [patients with baseline area of CNV (mm2) ≥ 2.54: OR 1.00, > 2.54 to ≤ 5.08: OR 0.71 CI 0.47, 1.07, > 5.08 to ≤ 10.2: OR 0.67, CI 0.38, 1.18, cannot measure: OR 0.44, CI 0.25, 0.76, p = 0.04].

Number of Injections

Eleven studies explored the impact of the number of injections on visual outcomes [10, 13, 16, 21, 22, 27, 30, 32, 33, 35, 36] (please see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material), with all of these studies finding the number of injections to be a statistically significant predictor of visual outcomes. The overall effect of the number of injections on visual acuity was that a greater change in VA was seen as the number of injections increased, with an average per year of 8–12 injections needed as an optimum number. It was not statistically possible to combine the data from studies to calculate a statistical effect size and confidence intervals.

The study with the largest sample size [22] found that the number of injections was a statistically significant predictor of VA change at both years 1 and 2 (Y1: 5.41, 95% CI 2.44–8.38. Y2: 1.93, 95% CI 0.85–3.02).

Discussion

Key Findings

The main finding of this review was that a higher numbers of anti-VEGF injections received, a lower age at baseline and smaller lesion size at baseline were all factors that positively influenced the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy. Higher visual acuity at baseline positively influenced the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy at longer time points of at least 2 years. The review also found that age, visual acuity and lesion size at baseline were more likely to be detected in larger, international studies of clinical trial data than in small, retrospective single-centre studies. There are some who would argue, however, that studies of routine data, although much smaller in sample size, are more representative of real-world patient populations. Although this is a valid argument, the collection of routine clinical data is unlikely to be of equal quality to data collection in clinical trials. Nevertheless, the, number of injections was detected as a significant factor in all types of studies, including smaller retrospective studies. The main findings of this review appear to be in keeping with the general body of literature on factors affecting visual outcome in nAMD.

The papers in this review suggest that the optimal number of injections for patients to avoid above average visual loss is 8–12 per year. However, many services may fail to deliver this due to high demand and shortages of staff. It must also be asked whether better VA outcome leads to better patient-reported outcomes. Do patients with better VA outcomes report better outcomes in terms of quality of life?

Impact of Study Quality on Results

As described earlier, all the included studies were of good quality. It is therefore concluded that the quality of the studies had no impact on the results of the review. The studies that were retrospective reviews of clinical trial data were rated as slightly lower in quality than the prospective and retrospective studies of hospital data, as the trial participants were potentially a selective sample of the study population. However, the trial populations did have larger sample sizes.

Differences Between Statistically Significant and Non-Significant Study Findings

Age

When considering all of the studies that looked at age together, there were some differences between those that found age to be a statistically significant predictor of visual outcomes and those that did not. The studies that found age to be a statistically significant predictor of visual outcomes were largely international multicentre trial data, with large data sets of at least 500 patients in all but one study. The studies that did not find age to be a predictor were generally single-centre retrospective reviews of routine data, with all but one study having sample sizes of less than 300. This suggests that larger sample sizes of at least 500 participants are needed to detect the effect of age on visual outcomes. It may also be linked to the fact that trial data tend to be more comprehensive, with fewer missing data, than routine clinical data. However, despite their much larger sample sizes, it could be argued that studies of trial data recruit patients according to strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, and therefore although studies of routine data tend to have much smaller sample sizes, they are more representative of real-world patient populations.

Baseline VA

There were similar differences between studies that found baseline visual acuity to be a statistically significant factor and those that did not. Of the studies that found visual acuity to be a statistically significant factor, most had international study populations, were multicentre and had large sample sizes, and many studies involved clinical trial data. The studies that did not find baseline visual acuity to be a statistically significant factor were all retrospective studies of routine clinical data, were all carried out in only one country, and all bar one were single-centre studies and had small sample sizes of less than 100. The one study that did have a larger sample size of 1063 and was a multicentre study was carried out in the Czech Republic. Therefore, it seems that larger sample sizes are needed to detect the influence of baseline visual acuity, and that large international trial data are more likely to do this. It is acknowledged that patients with better VA at baseline tend to have better VA at years 1 and 2, but some of the studies in this review did show differences in the number of letters gained and lost between patients.

Lesion Size

The difference between the studies that did not find lesion size to be a statistically significant factor and those that did is that those who did not find it to be a statistically significant factor were all retrospective studies of routine clinical data, with just 1–2 study centres in just one country. None of these studies had a sample size larger than 150. The studies that did find lesion size to be a statistically significant factor were again mostly larger, international studies of clinical trial data. Once again, it also seems that the effect of lesion size at baseline is more likely to be detected in large, international, multicentre clinical trial data than in smaller retrospective studies of routine data. Figure 4 shows this distribution of studies and their sample sizes.

Number of Injections

The fact that all the studies identified number of injections as a statistically significant clinical factor indicates that it had a highly detectable effect size, so that even smaller, retrospective studies of routine data were able to detect it, not just large, international clinical trial data.

Lack of Standardisation of Reported Data

The intention of this review was to identify factors that influence the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy. It was originally intended to pool the studies in a meta-analysis to quantify the magnitude of the individual factors on visual outcomes, but given the poor reporting, this was not possible. There was a lack of standardisation in the reporting of data in the included studies, with many not reporting results in enough detail. For example, 17 of the 30 papers included in this review simply presented p values with no inclusion of mean values or standard deviations (SDs) (or information to calculate the SD). Therefore, a literature review of the evidence was undertaken.

Limitations of the Review Process

During the review process, it was not possible to access one eligible paper; however, this is unlikely to have significantly changed the findings. The authors do acknowledge the possibility that other eligible papers may have been missed during the screening process. This review is also limited by the inclusion of only papers that were published in English, which could have introduced bias. It is also limited by the fact that perhaps papers that did not have significant findings may not have published their work. However, attempts were made to search unpublished literature.

It is acknowledged that one of the studies [22] was a study of the use of pegaptanib, which is no longer used in the treatment of nAMD. However, its findings on the effectiveness of treatment in terms of clinical and demographic factors was deemed relevant by the authors. It is also acknowledged that studies that used VA rather than best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) were included in this study, even though BCVA is a more accurate measure. However, again, the results of these studies were still considered to be relevant by the authors.

Factors Not Reported On

Medical History

Although this review reported on age and gender, there was only one paper identified that looked at other demographic factors [e.g. smoking status, body mass index (BMI) and past medical history such as stroke and diabetes], none of which was found to be statistically significant.

Socioeconomic Status

None of the included papers looked at socioeconomic status.

Individual Anti-VEGF Agents

This review did not examine the effects of individual anti-VEGF agents, because there already exist a significant number of comparative head-to-head studies. The review similarly did not look at genetic factors, because this has already been well reported in current evidence.

Ethnicity

This review did aim to examine ethnicity, but there was insufficient evidence available to comment on this.

Clinical Implications of Results

Which Results Are Modifiable?

Treatment regimen is modifiable, and identifying factors which impact on early diagnosis, start date, length of treatment and intensity may lead to improved outcomes and quality of life. Although age clearly cannot be considered a modifiable factor, time to diagnosis can be. This poses questions around whether more needs to be done to diagnose nAMD cases and start treatment promptly. Current guidelines recommend that on diagnosis of nAMD, treatment should be commenced within 2 weeks [3]. This review also identified number of injections as a modifiable factor, which also raises questions around whether service provision is currently adequate, and whether improvements to service provision are needed in terms of capacity, demand and accessibility. The goal of treatment should be to avoid undertreatment. These modifiable factors also pose questions to clinicians around whether addressing such factors has any impact on reported quality of life for these patients. This matters, because if addressing factors that affect visual outcome does not lead to improvements in quality of life, it could lead to future consideration of allocation of resources. It is not yet known how variation in the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy affects quality of life. Even in patients with good VA outcome, quality of life may be affected by having to undergo treatment and regular hospital visits. However, there may also be other modifiable factors that we are not aware of. The results of this review highlight the importance of patients receiving early anti-VEGF injections to achieve the best possible visual outcomes. This means that the role that the factors studied in this review play in the variation in visual outcomes in patients with nAMD needs to be investigated and addressed in future research. Future research must also address the need for more standardisation in how observational studies in the field of nAMD are reported.

Unanswered Questions

-

Are there other modifiable factors that influence the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy?

-

What can be done to improve early access to diagnosis and treatment, and to address any gaps in service provision?

-

Does variation in VA outcome affect quality of life?

Conclusions

This review has demonstrated that there is some evidence of clinical and demographic factors that affect the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy and hence the variation in VA outcome. It revealed that better visual acuity at baseline, smaller lesion size when present, lower age at baseline, and receipt of at least eight injections per year resulted in better visual outcomes for patients with nAMD who were treated with anti-VEGF therapy. However, this review was unable to identify as wide a range of factors as was hoped, and was unable to analyse the evidence that it did find in a meaningful statistical way.

The results also highlight the importance of clinicians and specialist nurses in ensuring timely diagnosis and commencement of treatment, and in ensuring adherence to treatment regimens.

References

Chakravarthy U, Evans J, Rosenfeld PJ. Age related macular degeneration. BMJ. 2010;340:c981. https://www.bmj.com/content/333/7574/869.

Owen CG, Fletcher AE, Donoghue M, Rudnicka AR. How big is the burden of visual loss caused by age related macular degeneration in the United Kingdom? Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:312–7. https://bjo.bmj.com/content/87/3/312.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Guidelines for Management. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/2013-SCI-318-RCOphth-AMD-Guidelines-Sept-2013-FINAL-2.pdf. Accessed 21 Nov 2017.

Cruess AF, Zlateva G, Xu X, Soubrane G, Pauleikhoff D, Lotery A, Mones J, Buggage R, Schaefer C, Knight T, Goss TF. Economic burden of bilateral neovascular age-related macular degeneration: multi-country observational study. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:57–73. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200826010-00006.

Rosenfeld P, Brown D, Heier J, Boyer D, Kaiser P, Chung C, Kim R. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–31. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa054481.

Brown D, Kaiser P, Michels M, Soubrane G, Heier J, Kim R, Sy J, Schneider S, ANCHOR Study Group. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–44.

Schmidt-Erfurth U, Kaiser P, Korobelnik J, Brown D, Chong V, Nguyen Q, Ho A, Ogura Y, Simader C, Jaffe G, Slakter J, Yancopoulos G, Stahl N, Vitti R, Berliner A, Soo Y, Anderesi M, Sowade O, Zeitz O, Norenberg C, Sandbrink R, Heier J. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: ninety-six-week results of the VIEW studies. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.011.

Johnston RL, Lee AY, Buckle M, Antcliffe R, Bailey C, McKibbin M, Chakravarthy U, Tufail A, UK AMD EMR User Groups. UK age-related macular degeneration electronic medical record system (AMD EMR) users group report IV: incidence of blindness and sight impairment in ranibizumab-treated patients. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(11):2386–92. https://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(16)30743-6/fulltext.

Pedrosa A, Sousa T, Pinheiro-Costa J, Beato J, Falcao M, Falcio-Reis F, Carneiro A. Treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with anti-VEGF agents: predictive factors of long-term visual outcomes. J Opthalmol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4263017.

Tufail A, Xing W, Johnston R, Akerele T, McKibbin M, Downey L, Natha S, Chakravarthy U, Bailey C, Khan R, Antcliff R, Armstrong S, Varma A, Kumar V, Tsaloumas M, Mandal K, Bunce C. The neovascular age-related macular degeneration database: multicenter study of 92 976 ranibizumab injections: report 1: visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1092–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.031.

Department of Health. Operational productivity and performance in English NHS acute hospitals: unwarranted variations. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/productivity-in-nhs-hospitals. Accessed 24 Jan 2019.

NICE. Age-related macular degeneration. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng82/chapter/Recommendations-for-research. Accessed 25 Jan 2019.

Liew G, Lee A, Zarranz-Ventura J, Stratton I, Bunce C, Chakravarthy U, Lee C, Keane P, Sim D, Akerele T, McKibbin M, Downey L, Natha S, Bailey C, Khan R, Antcliff R, Armstrong S, Varma A, Kumar V, Tsaloumas M, Mandal K, Egan C, Johnston R, Tufail A. The UK neovascular AMD database report 3: inter-centre variation in visual acuity outcomes and establishing real-world measures of care. Eye. 2016;30(11):1462–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.149.

Bloch S, la Cour M, Sander B, Hansen L, Fuchs J, Lund-Anderson L, Larsen M. Predictors of 1-year outcome in neovascular age-related macular degeneration following intravitreal ranibizumab treatment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:42–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02268.x.

Chae B, Jung J, Mrejen S, Gallego-Pinazo R, Yannuzzi N, Patel S, Chen C, Marsiglea M, Boddu S, Bailey Freund K. Baseline predictors for good versus poor visual outcomes in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy [abstract]. Retina. 2015;5040–7. https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2423305.

Chatziralli I, Nicholson L, Vrizidou E, Koutsiouki C, Menon D, Sergentanis T, Citu M, Hamilton R, Patel P, Hykin P, Sivaprasad S. Predictors of outcomes in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration switched from ranibizumab to 8-weekly aflibercept. Am Acad Ophthalmol. 2016;123:1762–70.

Chrapek O, Jarkovsky J, Sin M, Studnicka J, Kolar P, Jirkova B, Dusek L, Pitrova S, Rehak J. Prognostic factors of early morphological response to treatment with ranibizumab in patients with wet age-related macular degeneration. J Ophthalmol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/867479.

Fang K, Tian J, Qing X, Li S, Hou J, Li J, Yu W, Chen D, Hu Y, Li X. Predictors of visual response to intravitreal bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. J Ophthalmol. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/676049.

Guber J, Josifova T, Henrich P, Guber I. Clinical risk factors for poor anatomic response to ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Open Ophthalmol J. 2014;8:3–6.

Van Asten F, Rovers M, Lechanteur Y, Smailhodzic D, Meuther P, Chen J, den Hollander A, Fauser S, Hoyng C, van der Wilt G, Klevering B. Predicting non-response to ranibizumab in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014;21(6):347–55.

Gupta A, Raman R, Biswas S. Comparison of two intravitreal ranibizumab treatment schedules for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(3):386–90.

Holz F, Tadayoni R, Beatty S, Berger A, Cereda M, Hykin P, Staurenghi G, Wittrup-Jensen K, Altemark A, Nilsson J, Kim K, Sivaprasad S. Key drivers of visual acuity gains in neovascular age-related macular degeneration in real life: findings from the AURA study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(12):1623–8.

Korb C, Zwiener I, Lorenz K, Mirshahi A, Pfeiffer N, Toffelns B. Risk factors of a reduced response to ranibizumab treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration—evaluation in a clinical setting. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013;20:18–34.

Regillo C, Busbee B, Ho A, Ding B, Haskova Z. Baseline predictors of 12-month treatment response to ranibizumab in patients with wet age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(5):1014–23.

Ying G, Maguire M, Daniel E, Ferris F, Jaffe G, Grunwald J, Toth C, Huang J, Martin D. Association of baseline characteristics and early vision response with 2-year vision outcomes in the comparison of AMD treatments trials (CATT). Ophthalmology. 2015;122(12):2523–31.

Rush R, Simunovic M, Vandiver L, Aragon A, Ysasaga J. Treat-and-extend bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the importance of baseline characteristics. Retina. 2014;34(5):846–52.

Airody A, Venugopal D, Allgar V, Gale R. Clinical characteristics and outcomes after 5 years pro re nata treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with ranibizumab. Acta Opthalmol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.12618.

Chhablani J, Kim J, Freeman W, Kozak I, Wang H, Cheng L. Predictors of visual outcome in eyes with choroidal neovascularization secondary to age related macular degeneration treated with intravitreal bevacizumab monotherapy. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6:62–6.

El-Mollayess G, Mahfoud Z, Schakal A, Salti H, Jaafar D, Bashshur Z. Intravitreal bevacizumab in the management of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: effect of baseline visual acuity. Retina. 2013;33(9):1828–35.

Gale R, Korobelnik J, Yang Y, Wong T. Characteristics and predictors of early and delayed responders to ranibizumab treatment in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a retrospective analysis from the ANCHOR, MARINA, HARBOR, and CATT trials. Ophthalmologica. 2016;236(4):193–200.

Jonas J, Tao Y, Rensch F. Bilateral intravitreal bevacizumab injection for exudative age-related macular degeneration: effect of baseline visual acuity. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2011;27(4):401–5.

Ozkaya A, Alkin Z, Osmanbasoglu O, Ozkaya H, Demirok A. Intravitreal ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration patients with good baseline visual acuity and the predictive factors for visual outcomes. J Fr Ophthalmol. 2014;37(4):280–7.

Razi F, Haq A, Tonne P, Logendran M. Three-year follow-up of ranibizumab treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration: influence of baseline visual acuity and injection frequency on visual outcomes. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:313–9.

Shona O, Gupta B, Vemala R, Sivaprasad S. Visual acuity outcomes in ranibizumab-treated neovascular age-related macular degeneration; stratified by baseline vision. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;39(1):5–8.

Subhi Y, Sørensen T. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration in the very old (≥ 90 years): epidemiology, adherence to treatment, and comparison of efficacy. J Ophthalmol. 2017.

Calvo P, Abadia B, Ferrares A, Ruiz-Moreno O, Lecinena J, Torron C. Long-term visual outcome in wet age-related macular degeneration patients depending on the number of ranibizumab injections. J Ophthalmol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/820605.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge specialist librarian David Brown, University of York, for his assistance in developing the search strategy for this review.

Funding

This study and Rapid Service Fee were funded as part of a PhD studentship by Bayer UK (Grant no. UKBAY09160131).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

This manuscript is based on work that was previously presented at the British Gerontological Society Conference, July 2019, Liverpool, United Kingdom.

Disclosures

Claire Gill is in receipt of a PhD studentship from Bayer UK. Bayer UK had no input on this work or the findings. Catherine Hewitt, Tracy Lightfoot and Richard Gale have no conflict of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12746495.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gill, C.R., Hewitt, C.E., Lightfoot, T. et al. Demographic and Clinical Factors that Influence the Visual Response to Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy in Patients with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review. Ophthalmol Ther 9, 725–737 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-020-00288-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-020-00288-0