Abstract

Introduction

Pain is the most common symptom prompting an emergency department visit and emergency physicians are responsible for managing both acute pain and acute exacerbations of chronic pain resulting from a broad range of illnesses and injuries. The responsibility to treat must be balanced by the duty to limit harm resulting from analgesics. In recent years, opioid-related adverse effects, including overdose and deaths, have increased dramatically in the USA. In response to the US opioid crisis, emergency physicians have broadened their analgesic armamentarium to include a variety of non-opioid approaches. For some of these therapies, sparse evidence exists to support their efficacy for emergency department use. The purpose of this paper is to review historical trends and emerging approaches to emergency department analgesia, with a particular focus on the USA and Canada.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative review of past and current descriptive studies of emergency department pain practice, as well as clinical trials of emerging pain treatment modalities. The review considers the increasing use of non-opioid and multimodal analgesic therapies, including migraine therapies, regional anesthesia, subdissociative-dose ketamine, nitrous oxide, intravenous lidocaine and gabapentinoids, as well as broad programmatic initiatives promoting the use of non-opioid analgesics and nonpharmacologic interventions.

Results

While migraine therapies, regional anesthesia, nitrous oxide and subdissociative-dose ketamine are supported by a relatively robust evidence base, data supporting the emergency department use of intravenous lidocaine, gabapentinoids and various non-pharmacologic analgesic interventions remain sparse.

Conclusion

Additional research on the relative safety and efficacy of non-opioid approaches to emergency department analgesia is needed. Despite a limited research base, it is likely that non-opioid analgesic modalities will be employed with increasing frequency. A new generation of emergency physicians is seeking additional training in pain medicine and increasing dialogue between emergency medicine and pain medicine researchers, educators and clinicians could contribute to better management of emergency department pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pain is the most common reason for seeking emergency department (ED) care and, as a presenting complaint, pain accounts for up to seventy percent of ED visits [1]. Descriptive studies of ED pain practice began appearing in the 1990s and many of these investigators discovered that specific patient subgroups were at risk for inadequate pain treatment. Those at risk included the very young, older adults and members of minority ethnic groups [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. A number of efforts to increase awareness of unmet pain treatment needs, both in the ED and other settings, originated in the USA and Canada in the mid-1990s [10]. Educational campaigns to promote pain treatment became widespread throughout the healthcare system and, in particular, an increased emphasis on standardized pain assessment was promulgated by the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, soon to be renamed The Joint Commission [11].

As a consequence of these efforts, and in part due to industry marketing, pharmacologic approaches to pain treatment (particularly the use of opioids) became more aggressive. The opioid-centric nature of this change in practice soon became apparent, as the number of opioids prescribed by all healthcare providers increased dramatically over the following decade. US opioid prescribing peaked in 2010 at 782 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per capita. As of 2015, this volume had decreased to 640 MME per capita, but remained three times higher than levels in 1999 [12].

Importantly, the USA ranks number one in the consumption of prescription opioids globally, with a per capita consumption rate two to three times that of European countries [13]. Recent studies of prescription opioid misuse and abuse in Canada and Australia suggest increasing levels of harm while countries of the European Union report disparate rates of prescription opioid abuse [14,15,16]. The reasons for these cross-national consumption disparities are no doubt complex, related to multiple cultural and pharmaceutical marketing differences, and beyond the scope of this review.

In this paper, we present a qualitative review of past and current descriptive studies of ED pain practice, as well as clinical trials of emerging pain treatment modalities. Our purpose is to review historical trends and emerging approaches to ED analgesia, with a particular focus on the USA and Canada. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Current Standard Treatments and Approaches

A prospective, multicenter study published in 2007 provides a snapshot of US and Canadian ED practice at perhaps the height of an opioid-centric analgesic approach to pain treatment [17]. Investigators enrolled 842 patients age 8 years or older presenting to the ED with moderate to severe pain (> 3 on an 11-point numerical rating scale) to one of 20 EDs. Contrary to common belief that most ED pain results from injury or trauma, only 32% presented with pain of traumatic etiology (Table 1). Common nontraumatic diagnostic groups included neck and back pain, abdominal pain, headache, noncardiac chest pain and upper respiratory infection.

Pain intensity ratings on arrival ranged from 4 to 10 with a median pain score of 8. Only 50% of patients had a 2-point or greater reduction in numeric rating scale (NRS) pain intensity scores during the ED stay. Almost three quarters of patients were discharged in moderate pain (45%; NRS, 4–7) or severe pain (29%; NRS, 8–10).

Overall, 589 of 842 subjects (70%) expressed a desire for analgesics, and 506 of these (86%) received them. The median time interval from triage to analgesic administration was 90 min, and fewer than one third of patients received analgesics within 1 hour of arrival (Fig. 1). A total of 735 doses of 24 different analgesics were administered in the ED. The majority of analgesics administered were opioids (59%): morphine was the single most commonly administered analgesic (20%), followed by ibuprofen (17%; Table 2). Despite rather small reductions in pain intensity, patients expressed relatively high satisfaction with both overall pain treatment and staff responses to reports of pain (median scores of 5 on a 6-point scale; Fig. 2).

Reprinted from Todd et al. [17], with permission from Elsevier

Patient perceived need for, and administration of, analgesics.

Reprinted from Todd et al. [17], with permission from Elsevier

Patient satisfaction.

Over the first decade of the current century, evidence of prescription opioid-related harm, including overdose and death, became painfully obvious in the USA. Since 1999, overdose deaths involving prescription opioids, as well as total sales of prescription opioids, have quadrupled [18].

While it is difficult to estimate the precise contribution of ED opioid prescribing to the rise in prescription opioid harm in the USA, recent studies suggest that the contribution of emergency medicine is limited. In 2012, emergency medicine as a specialty accounted for only four percent of US opioid prescriptions, ranking behind dentists, surgeons, internists and family physicians [19]. The number of doses per prescription suggests an even smaller role for the specialty. In a study of 19 US EDs, 17% of patients received opioid prescriptions at discharge with an average of only 15 pills per prescription [20].

Nonetheless, over the last decade, initiatives to increase scrutiny of those seeking pain treatment in the ED, including widespread use of prescription drug monitoring programs, have become widespread [21]. Professional societies, regulatory bodies and individual EDs have created guidelines to limit and standardize opioid prescribing [22, 23]. As a result of these efforts, emergency physician opioid-prescribing rates dropped by almost ten percent between 2007 and 2012 [19]. With increasing frequency, emergency physicians are incorporating non-opioid alternatives and multimodal analgesic options into practice [24].

Emerging Treatments and Approaches

In the remainder of this review, we consider the increasing use of non-opioid and multimodal analgesic therapies, as well as the need for additional research and quality improvement activities to promote safe and effective ED pain management.

For treatment of some common ED pain presentations, such as benign headache, robust evidence exists to support non-opioid and migraine-specific modalities. Despite well-accepted evidence, progress toward standardizing US and Canadian ED headache treatment and giving primacy to non-opioid interventions of known efficacy (i.e., dopamine agonists, serotonin agonists) has been remarkably slow [25]. Almost 20 years after the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians published guidelines for the acute management of migraine headaches [26], evidence reviews reveal that opioids remain the first line of treatment for large proportions of US and Canadian ED patients with benign headaches [27,28,29,30]. While opioid administration is less common in non-North American EDs [31, 32], migraine-specific therapies are likely underutilized in ED settings worldwide. The crisis of prescription opioid harm in the USA provides additional stimulus to harmonize rational migraine therapy across national boundaries.

Emergency physician-administered regional anesthesia is another modality that is well supported by the literature and appears ripe for expansion. Fostered by the ubiquity of emergency medicine training programs in ultrasound, local and regional nerve blockade are increasingly employed for a large variety of painful injuries and illnesses [33,34,35,36].

A recent multicenter randomized controlled trial of regional nerve blockade for elderly patients with hip fractures illustrates the evolving role of emergency physicians in the delivery of regional anesthesia and the teamwork between emergency medicine and anesthesiology required to achieve optimal pain control and functional outcome for these often frail patients [37]. In this study, 161 ED patients with acute hip fractures from three New York City hospitals were randomized to receive either an ultrasound-guided, single-injection femoral nerve block administered by emergency physicians followed by placement of a continuous fascia iliaca block by anesthesiologists within 24 h, or opioid analgesics alone. Although both arms allowed opioids as needed, pain scores in the ED favored the intervention group over controls, as did pain scores on post-operative day 3 (Figs. 3, 4). Intervention subjects required one third fewer morphine milligram equivalents and reported fewer opioid adverse effects. Perhaps more surprisingly, intervention subjects reported superior functional status, including walking and stair climbing ability, up to 6 weeks after their initial fracture.

Reproduced with permission from Morrison et al. [37]

Mean pain scores with standard errors for pain at ED admission (baseline) and 1 and 2 h after admission for control (solid lines) and intervention (dashed lines).

Reproduced with permission from Morrison et al. [37]

Mean pain scores for pain at rest, with transfer out of bed, and with walking for control (shaded) and intervention (hashed) subjects on postoperative day 3.

Intravenous subdissociative-dose ketamine has also been the subject of a number of recent ED studies. Perhaps because ketamine has long been used for procedural sedation and as an induction agent for rapid sequence intubation, subdissociative-dose ketamine (0.1–0.4 mg/kg) as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy has become more rapidly adopted for use than other non-opioid analgesics.

In a recent position paper from the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, subdissociative-dose ketamine was judged safe and effective both as a single agent and in combination with opioids for the treatment of acute pain [38]. Although ketamine is well known to cause troubling neuropsychiatric adverse effects (emergence phenomena), in subdissociative doses these adverse effects appear to be minor and short-lived. Eight supportive studies of subdissociative-dose ketamine pertinent to pre-hospital and ED settings have been published over the last 10 years [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Another recent study examined adverse effects and analgesic efficacy of ketamine administered as either a single intravenous push (IVP) or a short infusion over 15 min [47]. Using a double-dummy design, the investigators reported similar analgesic efficacy with fewer reports of adverse effects for when ketamine was infused over a 15-min infusion period.

While subdissociative-dose ketamine, as either monotherapy or multimodal therapy, is generally supported by published evidence to date, emergency physicians should inform patients about potential side effects and avoid ketamine for patients with underlying psychiatric disorders or substance abuse-induced transient psychosis. Ketamine should be administered in accordance with established departmental policies and procedures.

Nitrous oxide has a long history of use as both an anxiolytic and analgesic among pediatric ED patients. Administered as a 50%–70% nitrous oxide vapor, it is used for children undergoing a number of procedures, including venipuncture, laceration repair, fracture reduction as well as incision and drainage of abscesses. Its use has been limited by the need for proper ventilation and scavenging equipment as well as the documented potential for staff recreational use [48]. Nitrous oxide has seen less use among adult ED patients. In a recent non-controlled pilot study of self-administered nitrous oxide among 85 ED patients with abscesses or orthopedic injuries, nitrous oxide appeared to be safe and well tolerated. Given the current emphasis on decreasing opioid use in the ED, it is likely that nitrous oxide use will increase over time [49].

In contrast to the modalities discussed above, a number of non-opioid analgesics for which there is less robust evidence are receiving increased attention. Analgesic therapies such as intravenous lidocaine, gabapentinoids, trigger point injections and even acupuncture, mind–body approaches and music therapy have recently been promoted for ED use [50].

Intravenous lidocaine has demonstrated efficacy for central pain syndromes and neuropathic pain, as well as opioid-sparing effects in the post-operative setting. Two Iranian research groups recently published studies of intravenous lidocaine for ED the treatment of renal colic. The first studied intravenous lidocaine as an adjuvant to opioid therapy in 110 patients presenting to the ED with typical renal colic symptoms [51]. The investigators reported that those treated with a combination of lidocaine and morphine reported fewer episodes of nausea and more rapid resolution of both pain and nausea than those treated with morphine alone. A second study of 240 patients with renal colic directly compared monotherapy with intravenous lidocaine to morphine [52]. Pain reduction was reported to be greater over the first 30 min for those treated with lidocaine. In another US study comparing intravenous lidocaine to intravenous ketorolac for ED patients with acute radicular back pain, lidocaine was less impressive, failing to reach a clinically significant reduction in reported pain intensity over 60 min [53].

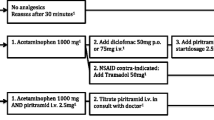

While intravenous lidocaine has thus far received limited investigation in the ED, other non-opioid and nonpharmacologic approaches, such as the use of gabapentinoids, trigger point injections and even acupuncture, mind–body therapies and music therapy, have received little rigorous study. Perhaps the most ambitious ED program encouraging non-opioid analgesic therapies as well as a variety of nonpharmacologic therapies is the Alternatives to Opiates Program (ALTO) developed by St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Patterson, New Jersey, USA [54]. Initiated formally in January 2016, ALTO encourages multimodal treatments for five specific conditions: acute low back pain, lumbar radiculopathy, renal colic, migraine and extremity fracture/dislocation. Condition-specific multimodal therapeutic protocols include a variety of non-opioid analgesics, specifically non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, ketamine, lidocaine/ropivacaine, benzodiazepines, corticosteroids, gabapentinoids and nitrous oxide. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia is advised for appropriate extremity fractures and dislocations. Although opioids are allowed as rescue analgesics in these protocols, alternatives to opioids are administered when possible. The program encourages discussions with patients of opioid adverse effects and addiction risks, and program goals include the incorporation of medically assisted treatment of opioid addiction, acupuncture and mind–body modalities. Although published data is limited, the program claims to have reduced opioid administration for selected conditions by almost 50%.

While this review concentrates on ED analgesics, the sole focus on pharmacologic intervention risks overlooking nonpharmacologic measures that can be employed effectively in the ED. Given the adverse effects associated with many opioid (and non-opioid) analgesics, it is important to understand and employ such treatments, including patient-centered communication techniques, physical interventions and relaxation techniques.

Additionally, for complaints such as pain, the emergency physician often lacks obvious confirmatory evidence of an inciting factor (e.g., migraine, low back pain). Those in pain often present with co-morbid anxiety and depression, or exhibit low self-efficacy, catastrophizing ideation or behaviors typical of chemical coping. Such patients may be perceived as “difficult” and challenge our professional competence and ability to maintain a positive therapeutic stance [55]. Negative stereotypes or stigmatization of those in pain impair the patient-physician relationship and predictably result in inadequate clinical care [56].

Particularly in the context of an ongoing national crisis of opioid harm, it is important that emergency physicians display empathy in treating patients who may (or may not) be at risk for opioid abuse. The concept of empathy for those in pain involves cognitive (the ability to envision standing in another’s shoes), affective (the appreciation of another’s emotional state) and action (patient-centered communication) elements. The ability to display empathy and provide patient-centered communication are core competencies for emergency physicians [57]. Patient-physician interactions characterized by empathy and trust are more likely to lead to optimal outcomes [58]. Although we lack sufficient ED research into the phenomenon, such “empathetic attention” has the potential reduce analgesic needs, particularly for patients with high levels of anxiety, and should be considered an integral tool in our therapeutic armamentarium [59].

Clinicians who successfully integrate these skills into practice will likely realize higher levels of patient satisfaction, enhanced treatment compliance and better clinical outcomes. To the extent that these practices promote patient self-efficacy and self-management of pain, healthcare costs related to unnecessary diagnostic imaging and adverse effects of inappropriate prescribing may also be reduced [60]. Finally, enhancing emergency physician empathy for those in pain has the potential to reduce career burnout [61, 62], increase physician well-being [63] and lower medicolegal risk [64].

Recent Developments and Conclusion

A number of recent developments are encouraging to those promoting excellence in ED pain management. After many years of discussion, emergency medicine residency training has become an accepted pathway into US pain medicine fellowships and a small but growing number of emergency physicians are now dual-certified in both specialties. Emergency physicians seeking dual certification will be more likely to pursue academic careers and promote a higher level of scholarship in pain-related emergency medicine, including the conduct of analgesic clinical trials pertinent to the ED. The recent publication of consensus-based recommendations for an emergency medicine pain management curriculum signals an increased interest in standardizing and enhancing the role of pain medicine in emergency medicine residency training [65]. Finally, the American College of Emergency Physicians has established a new Pain Management Section, with an inaugural meeting scheduled for late 2017. The Section’s goals are to promote further development of the subspecialty of pain medicine within emergency medicine, encourage additional research and education around the ED management of acute and chronic pain and ultimately develop an emergency medicine pain management fellowship with official recognition by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

Although the management of ED pain continues to challenge emergency physicians and our practice patterns evolve slowly, these are encouraging trends within our specialty that bode well for the future growth of a new subdiscipline of emergency medicine focused on the perennial problem of pain.

References

Cordell WH, Keene KK, Biles BK, Jones JB, Jones JH, Brizendine EJ. The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(3):165–9.

Brown JC, Klein EJ, Lewis CW, Johnston BD, Cummings P. Emergency department analgesia for fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(2):197–205.

Selbst SM, Clark M. Analgesic use in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(9):1010–3.

Friedland LR, Kulick RM. Emergency department analgesic use in pediatric trauma victims with fractures. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(2):203–7.

Jones JS, Johnson K, McNinch M. Age as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(2):157–60.

Hwang U, Belland LK, Handel DA, Yadav K, Heard K, Rivera-Reyes L, Eisenberg A, Noble M, Mekala S, Valley M, Winkel G, Todd KH, Morrison RS. Is all pain treated equally? A multicenter evaluation of acute pain care by age. Pain. 2014;155(12):2568–74.

Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA. 1993;269(12):1537–9.

Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, Goe L. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(1):11–6.

Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299(1):70–8.

Rupp T, Delaney KA. Inadequate analgesia in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(4):494–503.

Baker DW. History of the joint commission’s pain standards: lessons for today’s prescription opioid epidemic. JAMA. 2017;317(11):1117–8.

Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:697–704.

Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2016. https://www.incb.org/documents/Narcotic-Drugs/Technical-Publications/2016/Narcotic_Drugs_Publication_2016.pdf. Last accessed Oct 1, 2017.

Hauser W, Schug S, Furland AD. The opioid epidemic and national guidelines for opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: a perspective from different continents. Pain Rep. 2017;2(3):e599. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000000599.

Martins SS, Ghandour LA. Nonmedical use of prescription drugs in adolescents and young adults: not just a Western phenomenon. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):102–4.

King NB, Fraser V, Boikos C, Richardson R, Harper S. Determinants of increased opioid-related mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e32–42. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301966.

Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, Crandall CS, Fosnocht DE, Homel P, Tanabe P. Pain in the emergency department: results of the Pain and Emergency Medicine Initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain. 2007;8(6):460–6.

Prescription opioid overdose data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html. Last accessed Oct 1, 2017.

Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, US, 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:409–13.

Hoppe JA, Nelson LS, Perrone J, et al. Opioid prescribing in a cross section of US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:253–9.

Todd KH. Pain and prescription monitoring programs in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:24–6.

Cantrill SV, Brown MD, Carlisle RJ, Delaney KA, Hays DP, Nelson LS, O’Connor RE, Papa AM, Sporer KA, Todd KH. Clinical policy: critical issues in the prescribing of opioids for adult patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:499–525.

Juurlink DN, Dhalla IA, Nelson LS. Improving opioid prescribing: the New York City recommendations. JAMA. 2013;309:879–80.

Goett R, Todd KH, Nelson LS. Addressing the challenge of emergency department analgesia: innovation in the use of opioid alternatives. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2016;30(3):225–7.

Minen MT, Tanev K, Friedman BW. Evaluation and treatment of migraine in the emergency department: a review. Headache. 2014;54:1131–45.

Ducharme J. Canadian association of emergency physicians guidelines for the acute management of migraine headache. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:137–44.

Sahai-Srivastava S, Desai P, Zheng L. Analysis of headache management in a busy emergency room in the United States. Headache. 2008;48:931–8.

Vinson DR, Hurtado TR, Vandenberg JT, Banwart L. Variations among emergency departments in the treatment of benign headache. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:90–7.

Gupta MX, Silberstein SD, Young WB, et al. Less is not more: underutilization of headache medications in a university hospital emergency department. Headache. 2007;47:1125–33.

Colman I, Rothney A, Wright SC, Zilkalns B, Rowe BH. Use of narcotic analgesics in the emergency department treatment of migraine headaches. Neurology. 2004;62:1695–700.

Valade D, Lucas C, Calvel L, et al. Migraine diagnosis and management in general emergency departments in France. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:471–80.

Cvetković VV, Strineka M, Knezević-Pavlić M, Tumpić-Jaković J, Lovrencić-Huzjan A. Analysis of headache management in emergency room. Acta Clinica Croatica. 2013;52(3):281–8.

Dickman E, Pushkar I, Likourezos A, et al. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks for intracapsular and extracapsular hip fractures. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(3):586–9.

Heflin T, Ahern T, Herring A. Ultrasound-guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block for emergency management of a posterior elbow dislocation. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1324.e1–4.

Tezel O, Kaldirim U, Bilgic S, et al. A comparison of suprascapular nerve block and procedural sedation analgesia in shoulder dislocation reduction. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(6):549–52.

Frenkel O, Liebmann O, Fischer JW. Ultrasound-guided forearm nerve blocks in kids: a novel method for pain control in the treatment of hand-injured pediatric patients in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(4):255–9.

Morrison RS, Dickman E, Hwang U, Akhtar S, Ferguson T, Huang J, Jeng CL, Nelson BP, Rosenblatt MA, Silverstein JH, Strayer RJ, Torrillo TM, Todd KH. Regional nerve blocks improve pain and functional outcomes in hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2433–9.

Motov S, et al. Is there a role for intravenous subdissociative-dose ketamine administered as an adjunct to opioids or as a single agent for acute pain management in the emergency department? J Emerg Med. 2016;51(6):752–7.

Johansson P, Kongstad P, Johansson A. The effect of combined treatment with morphine sulphate and low-dose ketamine in a prehospital setting. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:61.

Jennings PA, Cameron P, Bernard S, et al. Morphine and ketamine is superior to morphine alone for out-of-hospital trauma analgesia: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:497–503.

Jennings PA, Cameron P, Bernard S. Ketamine as an analgesic in the pre-hospital setting: a systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55:638–43.

Galinski M, Dolveck F, Combes X, et al. Management of severe acute pain in emergency settings: ketamine reduces morphine consumption. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:385–90.

Ahern TL, Herring AA, Stone MB, Frazee BW. Effective analgesia with low-dose ketamine and reduced dose hydromorphone in ED patients with severe pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:847–51.

Beaudoin FL, Lin C, Guan W, Merchant RC. Low-dose ketamine improves pain relief in patients receiving intravenous opioids for acute pain in the emergency department: results of a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:1193–202.

Miller JP, Schauer SG, Ganem VJ, Bebarta VS. Low-dose ketamine vs morphine for acute pain in the ED: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:402–8.

Motov S, Rockoff B, Cohen V, et al. Intravenous subdissociative-dose ketamine vs. morphine for analgesia in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:222–9.

Motov S, et al. A prospective randomized, double-dummy trial comparing IV push low dose ketamine to short infusion of low dose ketamine for treatment of pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(8):1095–100.

Huang C, Johnson N. Nitrous oxide, from the operating room to the emergency department. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2016;4:11–8.

Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:269–73.

Hoffman J. An ER kicks the habit of opioids for pain. The New York Times; 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/14/health/pain-treatment-er-alternative-opioids.html?mcubz=3. Last accessed Sept 21, 2017.

Firouzian A, Alipour A, Rashidian Dezfouli H, Zamani Kiasari A, et al. Does lidocaine as an adjuvant to morphine improve pain relief in patients presenting to the ED with acute renal colic? A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(3):443–8.

Soleimanpour H, Hassanzadeh K, Vaezi H, Golzari SE, et al. Effectiveness of intravenous lidocaine versus intravenous morphine for patients with renal colic in the emergency department. BMC Urol. 2012;4(12):13.

Tanen DA, Shimada M, Danish DC, et al. Intravenous lidocaine for the emergency department treatment of acute radicular low back pain, a randomized controlled trial. J Emerg Med. 2014;47(1):119–24.

Innovative program targets five common pain syndromes with non-opioid alternatives. ED Manag. 2016;28(6):61–6. (PMID: 27295817).

De Ruddere L, Craig KD. Understanding stigma and chronic pain: a state-of-the-art review. Pain. 2016;157(8):1607–10.

Hooper C, Craig J, Janvrin DR, et al. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue among emergency nurses compared with nurses in other selected inpatient specialties. J Emerg Nurs. 2010;36(5):420–7.

Passik SD, Byers K, Kirsh KL. Empathy and the failure to treat pain. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5(2):167–72.

Thom DH, Stanford Trust Study Physicians. Physician behaviors that predict patient trust. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(4):323–8.

Tait RC. Empathy: necessary for effective pain management? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12(2):108–12.

Epstein RM, Franks P, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Miller KN, Campbell TL, Fiscella K. Patient-centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:415–21.

Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: a prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1338–40.

Sreenivas R, Wiechmann W, Anderson CL, et al. Compassion satisfaction and fatigue in emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):S51.

Shanafelt TD, West C, Zhao X, Novotny P, Kolars J, Habermann T, Sloan J. Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced empathy among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:559–64.

Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician–patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–9.

Poon SJ, Nelson LS, Hoppe JA, Perrone J, Sande MK, Yealy DM, Beeson MS, Todd KH, Motov SM, Weiner SG. Consensus-based recommendations for an emergency medicine pain management curriculum. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(2):147–54.

Acknowledgements

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The author meets the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and has given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Knox H. Todd has nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article, go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/C2DCF06008977E1B.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Todd, K.H. A Review of Current and Emerging Approaches to Pain Management in the Emergency Department. Pain Ther 6, 193–202 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-017-0090-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-017-0090-5