Abstract

Introduction

Little is known about the burden of hereditary transthyretin (ATTRv) amyloidosis, a genetic, progressive, and fatal disease caused by extracellular deposition of transthyretin amyloid fibrils. The study’s aim was to estimate costs and disease burden associated with ATTRv amyloidosis in a real-world setting.

Methods

Using IBM® MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental data, we identified patients at least 18 years of age with newly diagnosed ATTRv amyloidosis. Diagnosis required at least one medical claim with relevant diagnosis code (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] 277.30–.31, 277.39; ICD-10-CM E85.0–.4, E85.89, E85.9) between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016, and at least one additional criterion occurring during study period (2013–2017): at least 15 days diflunisal use without more than a 30-day gap; liver transplant; or claim with codes E85.1 or E85.2. First diagnosis date was study index. Continuous enrollment 1-year pre-index (baseline) and post-index (follow-up) was required. Patients with baseline amyloidosis diagnosis were excluded. Outcomes of interest were comorbidities and 1-year follow-up healthcare utilization and costs (also reported quarterly).

Results

Among 185 qualifying patients, mean age was 59.2 years (standard deviation 15.2), 54.1% were female, and baseline Charlson comorbidity index was 2.2 (2.5). Neuropathy (30.3%), diabetes (27.0%), and cardiovascular-related comorbidities, including dyspnea (25.9%) and congestive heart failure (21.6%), were common during follow-up. Nearly a quarter of patients (24.9%) were hospitalized during follow-up. Most hospitalizations and emergency department visits occurred in the first quarter post-diagnosis (18.9%, 17.8%, respectively) and dropped in subsequent quarters. The annual mean total cost was $64,066, with inpatient services contributing the majority of the expenses ($34,461), followed by outpatient ($23,853), and then pharmacy ($5752). As with utilization, costs were highest in the first quarter post-diagnosis and dropped in subsequent quarters.

Conclusion

Patients newly diagnosed with ATTRv amyloidosis have substantial healthcare utilization and costs in the first year, primarily the initial months, post-diagnosis. Further research should examine later costs associated with disease progression and end-of-life care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The economic burden of hereditary transthyretin (ATTRv) amyloidosis in the USA has not been quantified |

Previous studies of different variations of amyloidosis have shown significant healthcare utilization and costs associated with amyloidosis |

This study’s aim was to estimate the costs and disease burden associated with ATTRv amyloidosis in a real-world setting |

What was learned from the study? |

Patients newly diagnosed with ATTRv amyloidosis have substantial healthcare utilization and costs in the first year, primarily the initial months, following diagnosis |

Further research should examine later costs associated with disease progression and end-of-life care |

Introduction

Hereditary transthyretin (ATTRv) amyloidosis is a rare, progressive, multisystemic, and fatal form of amyloidosis caused by extracellular deposition of transthyretin amyloid fibrils primarily synthesized by the liver [1,2,3]. The worldwide prevalence is estimated to be around 50,000 based on the limited available data (e.g., clinical trial, survey, autopsy) [1, 4, 5], but this number is likely underestimated as a result of diagnostic uncertainty.

Patients with ATTRv amyloidosis commonly experience polyneuropathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, and autonomic, gastrointestinal, ocular, and renal dysfunction [1]. This varied symptom manifestation often results in misdiagnoses, with an accurate diagnosis taking multiple years and specialist visits [6,7,8]. For example, polyneuropathy symptoms have been mistakenly attributed to neuropathic conditions other than ATTRv amyloidosis, leading to misdiagnoses [1, 9,10,11]. If left untreated, symptoms worsen with death occurring 3–15 years after clinical presentation [1, 12]. Delayed diagnosis in amyloidosis is associated with poorer quality of life and productivity, as well as an increased disease burden [1, 5, 13,14,15].

Standard treatment options for ATTRv are limited, with organ transplantation being the primary approach [1]. However, transplant is associated with risks, such as morbidity due to chronic immunosuppression, and has been shown to be ineffective in the long-term improvement of quality of life and slowing of disease progression [1, 16, 17]. Several novel pharmacological options have been showing efficacy for treating early stages of ATTRv amyloidosis, including TTR stabilizers (e.g., tafamidis, diflunisal), RNA interference (RNAi) therapy (e.g., patisiran), and antisense oligonucleotides (e.g., inotersen) [18]. The above options, minus tafamidis, have been approved and are available for use in the USA.

The economic burden of ATTRv amyloidosis in the USA has not been quantified. The few articles examining burden and amyloidosis in a real-world setting have focused on other forms of amyloidosis, including systemic light chain (AL) amyloidosis and cardiac amyloidosis [19, 20]. These studies have indicated significant healthcare utilization and costs associated with amyloidosis, which we hypothesize would likely extend to the ATTRv form. This study’s aim was to estimate the costs and disease burden associated with ATTRv amyloidosis in a real-world setting.

Methods

This was a retrospective claims analysis of IBM® MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases.Footnote 1 The MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases represent health services of more than 41.1 million employees, dependents, and retirees in the USA with primary or Medicare supplemental coverage through privately insured fee-for-service, point-of-service, or capitated health plans. The databases include enrollment information and claims with healthcare utilization information (e.g., inpatient and outpatient services, and prescription drug claims) [21]. All data were compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Institutional review board approval was not required as MarketScan data are recorded in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. Meeting these conditions makes this research exempt from the requirements of 45 CFR 46.101 under the Department of Health and Human Services [22].

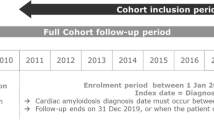

Adult patients with ATTRv amyloidosis were identified by the presence of at least one medical claim (inpatient or outpatient) for any form of amyloidosis, except light chain or wild type, (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes: 277.30, 277.31, 277.39; ICD-10-CM: E85.0, E85.1, E85.2, E85.3, E85.4, E85.89, E85.9) in any diagnosis field of a claim during the identification (ID) period (January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2016). Since diagnosis codes specific to hereditary amyloidosis (E85.1, E85.2) were not available until the introduction of ICD-10, patients included in the analysis who did not have one of these two codes were also required to have either (1) use of diflunisal for at least 15 days, or (2) liver transplant during the study period (January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2017). To identify newly diagnosed patients, patients who had a diagnosis of amyloidosis in the 1 year before index (washout period) were excluded. Additionally, we excluded patients who were not continuously enrolled for at least 1 year prior to the index (baseline period) and at least 1 year after index (follow-up period). The index date was the first diagnosis of amyloidosis in the ID period. See Fig. 1 for study time frame.

Baseline measures included patient demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, gender, region, insurance type, and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [23, 24]. Outcome measures of interest included inpatient and outpatient healthcare utilization (i.e., hospitalization, inpatient days, emergency department (ED) and physician office visits, and pharmacy utilization) and total costs (i.e., inpatient and outpatient services, and pharmacy). These measures were created using claims from the follow-up period. Additional measures included ATTRv-related comorbidities and selected procedures of interest, also created using claims from the follow-up period.

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations (SD), and relative frequencies and percentages for continuous and categorical data, respectively, were reported. Follow-up and outcome measures of interest were reported by quarter (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4) and at 1 year after index. All data transformations and statistical analyses were performed using SAS© version 9.4.

Results

Sample Selection and Patient Characteristics

Of the 9802 identified patients with at least one amyloidosis claim, 367 had either ICD-10-CM codes E85.1 or E85.2 or an additional qualifier for ATTRv amyloidosis. After removal of patients who were not continuously enrolled in a healthcare plan or who were not disease free during the baseline period, 253 patients remained. Of these, 68 patients were further excluded for not having 1-year continuous enrollment during follow-up. The final study sample consisted of 185 patients with ATTRv amyloidosis (Table 1).

The mean (SD) age of the study population was 59.2 (15.2) years, with the highest proportion of patients being in the 65+ age group (34.1%). The majority of patients were female (54.1%) and covered by Preferred Provider Organization (PPO)/Point of Service (POS) insurance (65.9%) (Table 2).

During the 1-year follow-up period, patients had a variety of nervous system, ocular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and metabolic comorbidities. Of these potentially ATTRv-related comorbidities, neuropathy affected the most patients [n (%) = 56 (30.3%)] and vitreous opacity the least [5 (2.7%)] (Fig. 2). Of the selected procedures performed during follow-up, electrocardiography and echocardiogram were the most common [55.7% and 38.4%, respectively (results not shown)].

Healthcare Utilization and Costs in the 1-Year Follow-Up

Nearly a quarter of patients (24.9%) were hospitalized in the year following diagnosis, with on average (SD) 20.2 (39.1) inpatient days annually among utilizers. Most hospitalizations and ED visits occurred in the first quarter following diagnosis (18.9%, 17.8%, respectively) and dropped in subsequent quarters (quarterly values shown in Table 3). The same trend was seen in the number of physician office visits (Table 3).

The 1-year mean (SD) total cost was $64,066 (214,317), with inpatient services contributing the majority of the expenses [$34,461 (179,301)], followed by outpatient [$23,853 (51,325)], and then pharmacy [$5752 (16,774)]. As with utilization, costs were highest in the first quarter following diagnosis and dropped in subsequent quarters (Fig. 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of nationally representative claims databases, we found that patients with ATTRv amyloidosis have substantial healthcare utilization and costs in the first year following diagnosis. The largest proportion of cost in the first year occurred in the first quarter after diagnosis.

This is the first real-world study examining healthcare costs associated with ATTRv amyloidosis in the USA. As such, there are no published cost estimates that are clearly comparable to our current estimates. A 2018 retrospective study focusing on amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis reported mean total annual all-cause healthcare costs of $122,180, with $56,466 from outpatient (including ED visits) and $54,053 from inpatient services. Total costs decreased from the first to second year after diagnosis, consistent with the decline we observed over a shorter period [20]. The earlier estimates were higher than ours, likely a result of clinical differences between the populations as patients with AL amyloidosis are more likely to have severe cardiac involvement than those with ATTRv amyloidosis [1, 25, 26]. A 2019 study of costs among hospitalized patients with cardiac amyloidosis (excluding hereditary forms) found mean total cost of $20,584 per admission [19]. However, neither the prior studies nor the current one estimated long-term healthcare utilization and costs. A 2018 survey of patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy found that patients in later stages of the disease had more ED visits and hospitalizations than those in earlier stages, but they did not estimate costs [27]. A real-world analysis incorporating longer follow-up in later stages of ATTRv amyloidosis would be informative, and we are contemplating such a study. Two recent international articles examined societal and public costs of ATTRv amyloidosis. A 2016 study of patients with ATTRv polyneuropathy in Portugal found a mean cost (including direct and indirect costs) per patient of €28,152 with treatment costs contributing the largest portion (52%) [28]. Similar to our study, Inês et al. found the greatest proportion of patients with amyloidosis in the older age groups [28]. Additionally, the study reported the greatest disease burden for this group [28]. A fiscal cost model found that patients with ATTRv amyloidosis in the Netherlands pay less taxes and receive incrementally more in government intervention, with the conclusion that halting disease progression early would result in economic benefits beyond health benefits [14]. In the simulated disease scenarios, patients with severe cardiomyopathy had less significant health costs due to early mortality compared to patients without severe cardiomyopathy. While not directly comparable to our study, both of these studies identified substantial burden and costs associated with the disease.

The current study provides the first real-world estimates of healthcare costs associated with ATTRv amyloidosis in the USA. These cost estimates may be useful for comparing the value of different treatment strategies, including any novel therapies that may emerge.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, our approach to patient identification has not validated using medical records; however, the majority of patients in the final sample were included because they had codes for hereditary amyloidosis (ICD-10-CM codes: E85.1 or E85.2), increasing our confidence that the correct population was identified. Second, the fixed 1-year follow-up period would have excluded those who died within 12 months of diagnosis, which might have resulted in an underestimate of cost. As information on disease stage is not available in the data source used, the patient population could have been skewed towards those patients with an earlier stage of ATTRv amyloidosis. This might have also resulted in an underestimate of costs, as chronic diseases generally incur higher costs over time due to disease progression [20, 29, 30]. Third, this study examines only direct healthcare costs and does not include indirect costs such as reduced work productivity. Moreover, while we did not examine the effect of demographic factors, such as age, on the burden of illness, we would expect to find greater burden in certain populations similar to what has been found in other amyloidosis studies [14, 28]. Additionally, costs prior to diagnosis, which may also contribute to burden, were not captured.

Conclusion

Quantifying the true economic burden of ATTRv amyloidosis remains a challenge due to diagnostic delays, lack of disease awareness, the disease’s rarity, and its wide variety of symptoms and clinical presentations. Patients newly diagnosed with ATTRv amyloidosis have substantial healthcare utilization and costs in the first year, primarily the initial months, following diagnosis. Further analysis is needed of longer-term—beyond 1 year through end-of-life—healthcare utilization and costs associated with ATTRv amyloidosis, and of the determinants of such burden.

Notes

MarketScan is a trademark of IBM Corporation in the USA and other countries.

References

Gertz MA. Hereditary ATTR amyloidosis: burden of illness and diagnostic challenges. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23:S107–S112112.

Ihse E, Ybo A, Suhr O, Lindqvist P, Backman C, Westermark P. Amyloid fibril composition is related to the phenotype of hereditary transthyretin V30M amyloidosis. J Pathol. 2008;216:253–61.

Koike H, Nishi R, Ikeda S, et al. The morphology of amyloid fibrils and their impact on tissue damage in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: an ultrastructural study. J Neurol Sci. 2018;394:99–106.

Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L, et al. Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2658–67.

Hawkins PN, Ando Y, Dispenzeri A, Gonzalez-Duarte A, Adams D, Suhr OB. Evolving landscape in the management of transthyretin amyloidosis. Ann Med. 2015;47:625–38.

Parman Y, Adams D, Obici L, et al. Sixty years of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy (TTR-FAP) in Europe: where are we now? A European network approach to defining the epidemiology and management patterns for TTR-FAP. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016;29(Suppl 1):S3–13.

Gertz MA, Benson MD, Dyck PJ, et al. Diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy of transthyretin amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2451–66.

Rossi K. New program may help cut time to diagnosis for hATTR patients. Rare Disease Report. 2018 Jun 21. https://www.raredr.com/news/new-program-may-help-cut-time-diagnosis-hattr-patients. Accessed 2018 Oct 29.

Ando Y, Coelho T, Berk JL, et al. Guideline of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis for clinicians. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:31.

Adams D, Suhr OB, Hund E, et al. First European consensus for diagnosis, management, and treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016;29:S14–S26.

Koike H, Hashimoto R, Tomita M, et al. Diagnosis of sporadic transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a practical analysis. Amyloid. 2011;18:53–62.

Koike H, Tanaka F, Hashimoto R, et al. Natural history of transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: analysis of late-onset cases from non-endemic areas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:152–8.

McCausland KL, White MK, Guthrie SD, et al. Light chain (AL) amyloidosis: the journey to diagnosis. Patient. 2018;11:207–16.

Connolly MP, Panda S, Patris J, Hazenberg BPC. Estimating the fiscal impact of rare diseases using a public economic framework: a case study applied to hereditary transthyretin-mediated (hATTR) amyloidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14:220.

Yarlas A, Gertz MA, Dasgupta NR, et al. Burden of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis on quality of life. Muscle Nerve. 2019;60:169–75.

Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O’Riordan WD, et al. Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:11–21.

Coelho T, Maia LF, Martins da Silva A, et al. Tafamidis for transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2012;79:785–92.

Luigetti M, Romano A, Di Paolantonio A, Bisogni G, Sabatelli M. Diagnosis and treatment of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) polyneuropathy: current perspectives on improving patient care. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:109–23.

Quock TP, Yan T, Tieu R, D’Souza A, Broder MS. Untangling the clinical and economic burden of hospitalization for cardiac amyloidosis in the United States. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;11:431–9.

Quock TP, Yan T, Chang E, Guthrie S, Broder MS. Healthcare resource utilization and costs in amyloid light-chain amyloidosis: a real-world study using US claims data. J Comp Eff Res. 2018. https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/10.2217/cer-2017-0100. Accessed 2018 Feb 15.

IBM Watson Health™. IBM MarketScan Research Databases for Health Services Researchers. Somers, NY: IBM Corporation; 2019 Apr. https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/6KNYVVQ2. Accesed 29 Oct 2018.

Department of Health and Human Services. Protection of Human Subjects. 45. Sect. CFR §46 Oct 1, 2005. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CFR-2005-title45-vol1/CFR-2005-title45-vol1-part46. Accesed 1 Apr 2020.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis: 2016 update on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:947–56.

Hassan W, Al-Sergani H, Mourad W, Tabbaa R. Amyloid heart disease. New frontiers and insights in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:178–84.

Schmidt H, Lin H, Agarwal S, et al. Impact of hereditary transthyretin mediated amyloidosis on use of health care services: an analysis of the APOLLO Study. Kumamoto, Japan; 2018. https://www.alnylam.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/3.-Healthcare-Burden_FINAL-1.pdf. Accesed 29 Oct 2018.

Inês M, Coelho T, Conceição I, Landeiro F, de Carvalho M, Costa J. Societal costs and burden of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis polyneuropathy. Amyloid. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13506129.2019.1701429.

Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:196.

Dunlay SM, Shah ND, Shi Q, et al. Lifetime costs of medical care after heart failure diagnosis. Circulation. 2011;4:68–75.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by Akcea Therapeutics, and Akcea will be responsible for the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Annual European Congress 2019, November 2–6, 2019, Copenhagen, Denmark; ISPOR 2018, May 19–23, 2018, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; AMCP Managed Care and Specialty Pharmacy Annual Meeting 2018, April 23–26, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Disclosures

Montserrat Vera-Llonch and Michael R. Pollock are employees of Akcea Therapeutics. Spencer Guthrie was an employee of Akcea Therapeutics at the time of study and is now an employee of Aurora Bio, San Francisco, CA, USA. Sheila R. Reddy, Eunice Chang, Ryan S. Tieu, Marian H. Tarbox, and Michael S. Broder are employees of Partnership for Health Analytic Research, LLC, which was paid by Akcea to perform the research described in this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Institutional review board approval was not required as MarketScan data are recorded in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. Meeting these conditions makes this research exempt from the requirements of 45 CFR 46.101 under the Department of Health and Human Services [22].

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to licensing restrictions, but are available with the permission of IBM Watson Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12249746.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

About this article

Cite this article

Reddy, S.R., Chang, E., Tarbox, M.H. et al. The Clinical and Economic Burden of Newly Diagnosed Hereditary Transthyretin (ATTRv) Amyloidosis: A Retrospective Analysis of Claims Data. Neurol Ther 9, 473–482 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-020-00194-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-020-00194-4