Abstract

The development of blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology as tools for screening the general population, and as the first step in a multistep process to determine which non-demented individuals are at greatest risk of developing AD dementia, is essential. Proteins that are reflective of AD pathology, such as amyloid beta 42 (Aβ42), tau proteins [total tau (T-tau) and phosphorylated tau (P-tau)], and neurofilament light chain (NfL), are detectable in the blood. However, a major challenge in measuring these blood-based proteins is that their concentrations are much lower in plasma or serum than in the cerebrospinal fluid. Single molecule array (SiMoA) is an ultrasensitive technology that can detect proteins in blood at sub-femtomolar concentrations (i.e., 10−16 M). In this review, we focus on the utility of SiMoA assays for the measurement of plasma or serum Aβ42, P-tau, T-tau, and NfL levels and discuss future directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A major challenge in measuring blood-based proteins of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) pathology is that their concentrations are much lower in plasma or serum than in cerebrospinal fluid. |

Single molecule array (SiMoA) is the most established ultrasensitive technology in the field of blood-based biomarkers of AD pathology from a research perspective. Kits to measure plasma or serum amyloid-beta (Aβ42), phosphorylated tau (p-Tau), total tau (T-tau), and neurofilament light chain (NfL) are available. |

Initial studies of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 support a potential role in screening for amyloid at the population level, but additional research is needed to ascertain the degree to which vascular factors affect plasma levels. |

Little research to date has examined blood phosphorylated tau using SiMoA. |

Blood neurofilament light chain and total-tau are promising non-specific markers of neurodegeneration and have shown potential as prognostic markers or as surrogate endpoints of neurodegeneration in clinical trials. |

Introduction

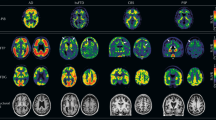

Within the context of developing disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), there is an urgent need to identify and validate biomarkers of AD pathology, such as amyloid-beta (Aβ), tau, and neurodegeneration. Based on the current state of science, the AT(N) scheme [β amyloid (A), pathological tau (T), and neurodegeneration (N)] of the new National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) Research Framework suggests cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) biomarkers for Aβ, tau, and neurodegeneration [1, 2]. Biomarkers of Aβ include amyloid PET imaging or MR Aβ42 imaging. Biomarkers of paired helical filament tau include CSF phosphorylated tau (P-tau) or PET tau imaging. Lastly, biomarkers of neurodegeneration include CSF total tau (T-tau), fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET hypometabolism, or atrophy in specific brain regions based on structural MRI. However, from the perspective of healthcare policy and economics, it is not feasible to quantify AD pathology at the population level using neuroimaging modalities (e.g., amyloid PET, tau PET, and MRI) nor is it feasible to conduct a lumbar puncture for the collection of CSF due to cost and resource availability. Thus, the development of blood-based biomarkers of AD pathology are essential for screening the general population, as well as for representing the first step in a multistep process to determine which non-demented individuals are at greatest risk of AD dementia [3]. It would also be more feasible to obtain serial measures of blood than to perform PET or CSF punctures when the goal is to assess the rate of disease progression and to determine the effect modification of potential therapies on the disease process.

The NIA-AA Research Framework left open the possibility of new markers of A, T, and N as new technologies are developed and new research shows the utility of the markers [1, 2]. Notably, proteins that are reflective of AD pathology, such as Aβ42, tau proteins (T-tau and P-tau), and neurofilament light chain (NfL), are detectable in blood. However, a major challenge in measuring these blood-based proteins is that their concentrations are much lower in plasma or serum than in the CSF. For example, the concentrations of Aβ42 [4] and tau [5] in plasma are approximately 30- and 100-fold lower, respectively, than those in the CSF. A second challenge is that plasma and serum have a higher total protein concentration (i.e., 50–70 g/L for an adult) and a more complex protein matrix than does the CSF. The binding of blood Aβ42 to many proteins in plasma or serum (e.g., albumin, lipoproteins, Aβ autoantibodies, fibrinogen, immunoglobulin, apolipoprotein J, apolipoprotein E, transthyretin, α-2-macroglobulin, serum amyloid p component, plasminogen, and amylin) [6,7,8,9] can further reduce the concentration of blood Aβ42 available for measurement. Current mainstream immunoassays typically measure proteins in blood at concentrations > 10−12 M [10]. Thus, more sensitive technologies are needed to quantify markers of AD pathology at blood concentrations in the range of 10−15 to 10−12 M.

Over the past few years, technologies such as single molecule array (SiMoA) [10], immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry (IP–MS) [11, 12], immunomagnetic reduction–superconducting quantum interference (MagQu) [13], and the interdigitated microelectrode sensor system [14] have emerged. These ultrasensitive technologies provide new opportunities for the development of blood-based biomarkers of AD pathology.

In this review, we focused on SiMoA assays for the measurement of AD-related blood-based biomarkers. Given the large and increasing number of articles reporting the use of SiMoA for the measurement of AD biomarkers, we did not conduct a comprehensive review of all articles but highlighted studies with the largest sample sizes or those that specifically examine certain aspects of the assays (i.e., stability over multiple freeze–thaw cycles). We first briefly review the measurement principle of SiMoA and then discuss published evidence on plasma or serum SiMoA assays (Aβ42 or Aβ42/Aβ40, T-tau, P-tau, and NfL) in the context of AD screening, diagnosis, and prognosis. We have attempted to distinguish between commercially available and home-brewed SiMoA assays when possible because home-brewed assays can perform differently and there may be a difference between blood plasma assay and serum assay results.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Measurement Principle of the SiMoA

Single molecule array is an ultrasensitive technology that can detect proteins in blood at sub-femtomolar concentrations (i.e., 10−16 M) [10]. Traditional immunoassays are conducted in a relative large reaction volume of 50–100 μL (e.g., wells in 96-well plates), which results in a diluted and diffuse signal molecule and limited sensitivity to the picomolar range (i.e., 10−12 M). In contrast, SiMoA restricts this diffusion by confining a single magnetic bead coupled with enzyme and substrate to femtoliter-sized wells. When the enzyme label catalyzes substrate conversion to a fluorescent product, the resulting fluorophores are confined to the well, creating a measurable fluorescence signal within a short period of time. The field of view of the camera encompasses hundreds of thousands of microwells; thus, thousands of single-molecule signals in the array can be counted simultaneously. The counting of active and inactive wells constitutes a digital signal corresponding to the presence or absence of single enzyme molecules. This extreme sensitivity permits the use of low quantities of labeling reagent, which in turn lowers nonspecific interactions and dramatically increases signal–background ratios [15]. To date, kits have been developed for measurement of Aβ40, Aβ42, T-tau, P-tau, and NfL in either the serum or plasma. In addition, a 3-plex of Aβ40, Aβ42, and T-tau and a 2-plex of Aβ42 and T-tau are currently available.

Blood-Based SiMoA Aβ40 and Aβ42 Assays

Amyloid-beta peptides of various lengths are found in the plasma or serum [16]. It has been estimated that 30–50% of the Aβ peptide pool in the central nervous system is transported to the blood for clearance [17]. The most commonly measured Aβ peptides examined in the context of AD are Aβ40 and Aβ42, which exist as both monomers and aggregates (i.e., oligomers) [14]. The SiMoA Aβ40 and Aβ42 assays utilize the same capture antibody targeting the N-terminus of Aβ40 and Aβ42 but different C-terminus detection antibodies, namely, 2G3 and 21F12, respectively [18]. The peptide standards for Aβ40 and Aβ42 are also made by different manufacturers: the SiMoA Aβ40 assay uses the Aβ1-40 peptide from AnaSpec (Fremont, CA, USA) and the SiMoA Aβ42 assay uses the Aβ1-42 peptide from Covance Inc. (Princeton, NJ, USA) [4]. Presumably, the SiMoA Aβ40 and Aβ42 assays measure monomeric forms of Aβ40 and Aβ42. A study examining the effect of up to four freeze–thaw cycles on Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations found no significant difference in plasma Aβ42 levels after four cycles [19], but there was a small reduction in plasma Aβ40 after the third freeze–thaw cycle and a further reduction after the fourth.

Some studies of the plasma AB40 and AB42 examine the AB42/AB40 ratio whereas other studies examine the AB40/AB42 ratio. The results are often similar but the direction is in the opposite direction (for example a high AB40/AB42 ratio vs. a low AB42/AB40 ratio). Studies of participants with subjective memory concerns have reported lower plasma Aβ42 levels and higher Aβ40/Aβ42 ratios compared to cognitively unimpaired controls without memory complaints [20, 21]. A number of studies have also examined the predictive ability of plasma Aβ42 level for brain amyloid. The best diagnostic cut-points for plasma Aβ42 had a sensitivity of 52% and a specificity of 78% for detecting elevated brain amyloid via amyloid PET or CSF amyloid; the sensitivity for the plasma Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio ranged from 76 to 78% and the specificity from 75 to 76%. Further, the plasma Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio slightly improved models to predict brain amyloid deposition after age was taken into consideration, 10-word delayed recall or the Mini-Mental State Examination score, and the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE) [22]. Taken together, this evidence suggests that the plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio as determined by SiMoA may have clinical utility for screening for elevated brain amyloid. Of note, however, studies have shown that vascular disease conditions, such as white matter lesions, cerebral microbleeds, hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease, can increase plasma Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40 levels measured by the SiMoA [4]. Therefore, additional research is needed to determine the degree to which vascular factors and other comorbidities affect plasma amyloid levels. The SiMoA HD-1 analyzer (Quanterix Corp., Billerica, MA, USA) has a throughput of 66 tests per hour, thus supporting a potential role in screening for amyloid at the population level [15].

Although the plasma level of Aβ42 and the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio measured by SiMoA have been shown to be lower in older adults with AD dementia than in cognitively unimpaired individuals [4], consistent with results using IP-MS methods [11, 12], a study using MagQu reported the opposite, namely, lower levels in AD dementia patients than in cognitively unimpaired individuals [13]. These contrasting plasma Aβ levels may be due to methodological differences between the assays. A major difference between the SiMoA and MagQu assays is that SiMoA resembles a traditional enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and uses monoclonal capture and detection antibodies, whereas MagQu uses polyclonal antibodies that specifically capture the C-terminal (amino acids 37–42) of Aβ42 [23]. The design of the MagQu assay is such that it has a higher probability of detecting Aβ42 in isolated, complex, or oligomeric forms [23]. Despite the differences in these methods, they are all ultrasensitive, and the results obtained suggest that measurement of the plasma Aβ42 level or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio may have potential clinical utility for screening general populations for elevated brain amyloid deposition.

Plasma SiMoA P-tau Assay

Although both CSF P-tau and T-tau are elevated in patients with prodromal AD or AD dementia, T-tau is also elevated in patients with stroke, traumatic brain injury, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease whereas P-tau is not [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Thus, P-tau is thought to be more specific to the pathophysiological state associated with the accumulation of AD-type tau pathology and is considered to be the ‘T’ in the AT(N) scheme of the NIA-AA Research Framework [1, 2].

Blood P-tau levels, however, have been difficult to measure due to their low levels. To date, only a few studies using the SiMoA platform have been published. Tatebe et al. [30] reported higher plasma P-tau 181 (pTau181) levels in 20 AD dementia patients compared to 15 age-matched controls (all purchased samples) and higher levels in 20 patients with Down syndrome compared to 22 age-matched controls. However, the authors did not use the pTau181 SiMoA kit for their assays; instead, they used the SiMoA-HD1 hTau kit and modified the detector reagent to use the AT270 mAb specific for pTau181. They also used a standard from a different kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) without providing sufficient sensitivity and specificity for the “new” assay [30]. Thus, interpretation of the results regarding their measurements of blood P-tau level is difficult. Another study using the pTau181 SiMoA kit reported that plasma pTau181 correlated with the severity of Braak tau staging, defined using tau PET AV-1451, among a group of 76 participants [52 cognitively normal, 9 with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and 15 with AD dementia] [31]. A limitation of this study was that plasma pTau181 was only quantifiable in 51 of the 76 participants, which is in contrast to plasma T-tau which was quantifiable in 75 of the 76 participants. The reasons for the lack of quantification of pTau181 in one-third of the participants were not discussed by the authors, but this limitation is concerning. A third study of 172 cognitively unimpaired participants, 57 participants with MCI, and 40 AD dementia patients reported that pTau181 levels were higher in AD dementia patients than in those who were cognitive unimpaired [32]. In addition, plasma pTau181 was more strongly associated with both amyloid and tau PET, compared to plasma T-tau, was a more sensitive and specific predictor of elevated brain amyloid than plasma T-tau, and was as good as, or better than, the combination of age and APOE. Although plasma T-tau in this study was measured using a SiMoA kit, measurement of pTau181 was performed on a streptavidin small spot plate using the Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) platform (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, USA) with different antibodies compared to the SiMoA kit. However, development of a pTau181 SiMoA kit with these different antibodies is currently being investigated. In addition to kits for measuring pTau181, a SiMoA kit for the measurement of P-tau 231 is available, but little research has been published with this kit to date.

Plasma SiMoA T-tau Assay

The commercially available SiMoA T-tau assay measures mid regions of tau protein isoforms, hence the term total tau (T-tau). Tau protein isoforms in the blood are different from those in the CSF in that full-length tau is the dominant isoform in plasma but not in the CSF. This difference suggests that the majority of plasma tau comes from peripheral sources rather than from the brain [33]. Using the SiMoA assay, levels of T-tau have been found to be stable up to four freeze–thaw cycles [19]. Indeed, plasma T-tau has been found to have weak correlations with CSF T-tau or P-tau and with Tau PET AV-1451 [32, 34, 35]. Elevated plasma T-tau and CSF T-tau have also been associated with differential brain atrophy patterns in gray matter density [36]. In one small study, however, the plasma T-tau/Aβ42 ratio was predictive of brain tau deposition [31].

Cross-sectional studies of the SiMoA total tau assay have shown elevated plasma T-tau levels in AD dementia patients compared to cognitively normal controls, as well as associations with lower cortical thickness [32, 34, 36, 37]. Higher levels have also been found in those with MCI compared to cognitively unimpaired controls, but there was considerable overlap in levels between diagnostic groups. In longitudinal studies, higher plasma T-tau levels been associated with cognitive decline and risk of MCI, and this association was independent of brain amyloid levels [38]. A more recent study reported, in two independent samples, that higher plasma T-tau levels were associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia and AD dementia as well as hippocampal volume loss [35]. However, pathological confirmation and amyloid PET data were not available to confirm the diagnosis of AD dementia, which was solely based on a clinical diagnosis.

Together, these results suggest that plasma T-tau, as measured by SiMoA, will not be a useful stand-alone biomarker for the diagnosis of preclinical or prodromal AD. Moreover, given that the association of plasma T-tau with cognition and MCI has been found to be independent of elevated brain amyloid, this marker is not specific to the pathophysiological process of AD. However, plasma T-tau could be useful as a prognostic marker of non-specific cognitive decline and neurodegeneration and fits into the AT(N) scheme of the new NIA-AA Research Framework as a potential blood-based measure of neuronal injury and neurodegeneration (‘N’) [1]. Additional research is therefore needed to elucidate what plasma T-tau is indicative of in terms of brain structure and function and which aspect of neurodegeneration. Plasma T-tau has been reported to be higher in those with a history of diabetes, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and myocardial infarction, suggesting the possibility that plasma T-tau could also be indicative of cerebrovascular pathology [37].

Plasma SiMoA Neurofilament Light Assay

Neurofilament light chain is a recognized biomarker of subcortical large-caliber axonal degeneration [39, 40]. Unlike T-tau, multiple studies have reported modest, yet similar, correlations between plasma and CSF NfL, ranging from 0.569 in the The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative to 0.590 in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging [41, 42]. Moreover, plasma NfL has been shown to have similar effect sizes to CSF NfL in terms of short-term change in cognition and imaging measures of neurodegeneration [42].

Historically, plasma NfL has been measured using ELISA technology and electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assay technology. However, the sensitivity of ELISA for quantifying plasma NfL has been found to be insufficient, and ECL is not sufficiently sensitive to detect the lowest concentrations of plasma NfL. Therefore, studies now utilize SiMoA technology for measuring blood NfL due to its higher sensitivity [43, 44]; in contrast, CSF NfL can be measured with other technologies because of the relatively higher concentration of NfL in the CSF. The levels of NfL are higher in serum than in plasma, but the majority of studies have utilized plasma to quantify NfL. A study utilizing serum NfL reported that concentrations were stable up to four freeze–thaw cycles [19]. In contrast, a study examining plasma NfL reported little change after one freeze–thaw cycle, but found that subsequent cycles were associated with slight but significant increases [45]. Whether the difference in the two studies is due to using plasma versus serum to quantify NfL is not known, but additional research is needed to clarify the effect of multiple freeze–thaw cycles on NfL measurements. In other analyses assessing the stability of plasma NfL, samples kept for 5 days at room temperature or stored in a refrigerator had higher plasma NfL levels than those which were subjected to rapid freezing [45].

Elevated plasma NfL levels have been found in multiple neurodegenerative conditions associated with neuronal axonal damage, including frontotemporal dementia [46], multiple sclerosis [47], traumatic brain injury [48], atypical parkinsonian disorders [49], and AD dementia [32, 50]. Thus, NfL is hypothesized to be a non-specific marker of neurodegeneration and, like T-tau, fits into the AT(N) scheme of the new NIA-AA Research Framework as a potential fluid-based measure of neuronal injury and neurodegeneration (‘N’). Indeed, among participants who are cognitively unimpaired or have MCI, the relationship between plasma or CSF NfL and longitudinal changes in cognition or brain imaging measures of neurodegeneration are independent of elevated brain amyloid [32, 50].

Cross-sectional studies have shown that blood NfL increases with increasing symptom severity across the clinical AD spectrum and as familial AD mutation carriers age comes closer to the estimated age of onset [51]. However, although significant differences in NfL levels are often shown in comparisons of AD dementia patients and cognitively normal individuals, with excellent accuracy based on the area under the curve, reports of significant differences between those with MCI and cognitively normal individuals have been mixed (e.g., [50, 52]). Individuals with more rapidly progressing neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., frontotemporal dementia, HIV-associated dementia) have higher levels of plasma NfL that do AD dementia patients because of the greater rate of axonal degeneration in the former diseases, but plasma NfL levels again have been found to overlap across diagnostic groups [53]. Thus, given the lack of disease specificity of blood NfL, or even CSF NfL, it is unlikely that NfL can be used as a diagnostic tool for AD [44].

In longitudinal studies, plasma NfL has been found to predict short- (15 months) and longer-term (up to 4 years) change in cognition among cognitively unimpaired individuals and those with a diagnosis of MCI or AD dementia [42, 52]. Rates of change in plasma NfL have also been found to correlate with rates of change in cognition, CSF Aβ42 and P-tau markers, hippocampal volume loss, and FDG-PET hypometabolism [42, 52]. These results suggest that plasma NfL may be a useful as a prognostic marker of cognitive decline and neurodegeneration and to track longitudinal neurodegeneration in AD. This marker could also be useful as a surrogate endpoint of neurodegeneration in clinical trials.

Conclusion

The technological advances in the last decade have led to increasing opportunities to measure blood-based biomarkers of AD pathology, including Aβ42, Aβ40, P-tau, T-tau, and NfL. The development of ultrasensitive technologies has been particularly important in moving the field forward. SiMoA is the most established ultrasensitive technology in the field of blood-based biomarkers of AD pathology from the research perspective. However, it is still uncertain whether the current ultrasensitive technologies, including SiMoA, will be readily available in clinical laboratories for screening for AD pathology and longitudinally tracking neurodegeneration in AD patients. The translation of blood-based AD biomarkers into diagnostic biomarkers for routine use in patient care will involve many steps, including well-defined intended use, validation of analytical and clinical performance in the context of intended use, and regulatory approval (e.g., United States Food and Drug Administration). Even though regulatory approval may not be required for a biomarker to be used clinically [e.g., available as a laboratory-developed test through Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) by CLIA-certified clinical laboratories], the wide adoption of a clinical test is mainly driven by clinical needs. Clinical needs of blood-based biomarkers of AD pathology will most likely be driven by the availability of disease-modifying treatments and precision medicine (e.g., the right drug for the right patient). It remains to be seen whether SiMoA assays will be used in the clinical setting for patient care. Nevertheless, the exciting scientific evidence generated by SiMoA assays to date and in the future will continue to enhance and influence our understanding of AD.

References

Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–62.

Blennow K, Hampel H. CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(10):605–13.

O’Bryant SE, Mielke MM, Rissman RA, et al. Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer disease: current state of the science and a novel collaborative paradigm for advancing from discovery to clinic. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(1):45–58.

Janelidze S, Stomrud E, Palmqvist S, et al. Plasma beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26801.

Blennow K. A review of fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: moving from CSF to blood. Neurol Ther. 2017;6[Suppl 1]:15–24.

Kuo YM, Emmerling MR, Lampert HC, et al. High levels of circulating Abeta42 are sequestered by plasma proteins in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257(3):787–91.

Kuo YM, Kokjohn TA, Kalback W, et al. Amyloid-beta peptides interact with plasma proteins and erythrocytes: implications for their quantitation in plasma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268(3):750–6.

Ono K, Noguchi-Shinohara M, Samuraki M, et al. Blood-borne factors inhibit Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2006;202(1):125–32.

Biere AL, Ostaszewski B, Stimson ER, Hyman BT, Maggio JE, Selkoe DJ. Amyloid beta-peptide is transported on lipoproteins and albumin in human plasma. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(51):32916–22.

Rissin DM, Kan CW, Campbell TG, et al. Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(6):595–9.

Ovod V, Ramsey KN, Mawuenyega KG, et al. Amyloid beta concentrations and stable isotope labeling kinetics of human plasma specific to central nervous system amyloidosis. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(8):841–9.

Nakamura A, Kaneko N, Villemagne VL, et al. High performance plasma amyloid-beta biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2018;554(7691):249–54.

Yang SY, Chiu MJ, Chen TF, Horng HE. Detection of plasma biomarkers using immunomagnetic reduction: a promising method for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Ther. 2017;6[Suppl 1]:37–56.

Kim Y, Yoo YK, Kim HY, et al. Comparative analyses of plasma amyloid-beta levels in heterogeneous and monomerized states by interdigitated microelectrode sensor system. Sci Adv. 2019;5(4):eaav1388.

Wilson DH, Rissin DM, Kan CW, et al. The Simoa HD-1 analyzer: a novel fully automated digital immunoassay analyzer with single-molecule sensitivity and multiplexing. J Lab Autom. 2016;21(4):533–47.

Kaneko N, Yamamoto R, Sato TA, Tanaka K. Identification and quantification of amyloid beta-related peptides in human plasma using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2014;90(3):104–17.

Roberts KF, Elbert DL, Kasten TP, et al. Amyloid-beta efflux from the central nervous system into the plasma. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(6):837–44.

Lue LF, Guerra A, Walker DG. Amyloid beta and tau as Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers: promise from new technologies. Neurol Ther. 2017;6[Suppl 1]:25–36.

Keshavan A, Heslegrave A, Zetterberg H, Schott JM. Stability of blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease over multiple freeze–thaw cycles. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:448–51.

Verberk IMW, Slot RE, Verfaillie SCJ, et al. Plasma amyloid as prescreener for the earliest Alzheimer pathological changes. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(5):648–58.

Vergallo A, Megret L, Lista S, et al. Plasma amyloid beta 40/42 ratio predicts cerebral amyloidosis in cognitively normal individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(6):764–75.

Palmqvist S, Insel PS, Zetterberg H, et al. Accurate risk estimation of beta-amyloid positivity to identify prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: cross-validation study of practical algorithms. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(2):194–204.

Teunissen CE, Chiu MJ, Yang CC, et al. Plasma amyloid-beta (Abeta42) correlates with cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(4):1857–63.

Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(7):673–84.

Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, Mattsson N, et al. Detailed comparison of amyloid PET and CSF biomarkers for identifying early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;85(14):1240–9.

Hesse C, Rosengren L, Andreasen N, et al. Transient increase in total tau but not phospho-tau in human cerebrospinal fluid after acute stroke. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297(3):187–90.

Ost M, Nylen K, Csajbok L, et al. Initial CSF total tau correlates with 1-year outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1600–4.

Skillback T, Rosen C, Asztely F, Mattsson N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Diagnostic performance of cerebrospinal fluid total tau and phosphorylated tau in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: results from the Swedish Mortality Registry. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(4):476–83.

Buerger K, Otto M, Teipel SJ, et al. Dissociation between CSF total tau and tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 231 in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(1):10–5.

Tatebe H, Kasai T, Ohmichi T, et al. Quantification of plasma phosphorylated tau to use as a biomarker for brain Alzheimer pathology: pilot case–control studies including patients with Alzheimer’s disease and down syndrome. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):63.

Park JC, Han SH, Yi D, et al. Plasma tau/amyloid-beta1-42 ratio predicts brain tau deposition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2019;142(3):771–86.

Mielke MM, Hagen CE, Xu J, et al. Plasma phospho-tau181 increases with Alzheimer’s disease clinical severity and is associated with tau- and amyloid-positron emission tomography. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(8):989–97.

Chen Z, Mengel D, Keshavan A, et al. Learnings about the complexity of extracellular tau aid development of a blood-based screen for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):487–96.

Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Janelidze S, et al. Plasma tau in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2016;87(17):1827–35.

Pase MP, Beiser AS, Himali JJ, et al. Assessment of plasma total tau level as a predictive biomarker for dementia and related endophenotypes. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):598–606.

Deters KD, Risacher SL, Kim S, et al. Plasma tau association with brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(4):1245–54.

Dage JL, Wennberg AM, Airey DC, et al. Levels of tau protein in plasma are associated with neurodegeneration and cognitive function in a population-based elderly cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(12):1226–34.

Mielke MM, Hagen CE, Wennberg AMV, et al. Association of plasma total tau level with cognitive decline and risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia in the Mayo Clinic Study on Aging. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(9):1073–80.

Hoffman PN, Cleveland DW, Griffin JW, Landes PW, Cowan NJ, Price DL. Neurofilament gene expression: a major determinant of axonal caliber. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(10):3472–6.

Norgren N, Rosengren L, Stigbrand T. Elevated neurofilament levels in neurological diseases. Brain Res. 2003;987(1):25–31.

Khalil M, Teunissen CE, Otto M, et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(10):577–89.

Mielke MM, Syrjanen JA, Blennow K, et al. Plasma and CSF neurofilament light: relation to longitudinal neuroimaging and cognitive measures. Neurology. 2019;93(3):e252–60.

Disanto G, Barro C, Benkert P, et al. Serum neurofilament light: a biomarker of neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(6):857–70.

Gaetani L, Blennow K, Calabresi P, Di Filippo M, Parnetti L, Zetterberg H. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(8):870–81.

Lewczuk P, Ermann N, Andreasson U, et al. Plasma neurofilament light as a potential biomarker of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):71.

Scherling CS, Hall T, Berisha F, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament concentration reflects disease severity in frontotemporal degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(1):116–26.

Teunissen CE, Dijkstra C, Polman C. Biological markers in CSF and blood for axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(1):32–41.

Shahim P, Gren M, Liman V, et al. Serum neurofilament light protein predicts clinical outcome in traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36791.

Hansson O, Janelidze S, Hall S, et al. Blood-based NfL: a biomarker for differential diagnosis of parkinsonian disorder. Neurology. 2017;88(10):930–7.

Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Association of plasma neurofilament light with neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(5):557–66.

Preische O, Schultz SA, Apel A, et al. Serum neurofilament dynamics predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2019;25(2):277–83.

Mattsson N, Cullen NC, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Association between longitudinal plasma neurofilament light and neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(7):791–9.

Bridel C, van Wieringen WN, Zetterberg H, et al. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein in neurology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1534.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Effort for this work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging grants U01 AG006786, R01 AG049704, and R01 AG059654. No funding was received for the publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Danni Li receives research support from NIH and Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Michelle Mielke served as a consultant to Eli Lilly and receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Defense, and unrestricted research grants from Biogen.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9792602.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Mielke, M.M. An Update on Blood-Based Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease Using the SiMoA Platform. Neurol Ther 8 (Suppl 2), 73–82 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00164-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00164-5