Abstract

Purpose

Persistence of herbicides in soil is a major concerning world issue due to their negative impacts on environment and human health. Laboratory and bioassay experiments were conducted to evaluate the effects of municipal waste compost (MC) and sheep manure (SM) on metribuzin degradation and phytotoxicity of this herbicide.

Methods

In degradation studies, soil samples were mixed separately with amendments at a rate of 2.5% (w/w) and metribuzin at a concentration of 5 mg kg−1 soil was used for fortification of selected samples. A liquid extraction method was chosen and final extracts were analyzed by HPLC. In bioassay study, the phytotoxic effects of different concentrations of metribuzin (0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 1 mg kg−1 soil) on oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) were evaluated.

Results

The results indicated 88.8% degradation of metribuzin in MC during 120-day period followed by SM recording 72.2%, compared to non-amended soil where 59.8% of metribuzin were removed. The half-life was 119.48 days in non-amended soil as compared to 87.72 and 103.43 days in MC and SM application, respectively. MC was the most efficient treatment to accelerate metribuzin dissipation from the soil. Bioassay results showed that metribuzin residues had a negative effect on root and shoot biomass of oilseed rape. However, the root parameter was more sensitive than the shoot.

Conclusions

It could be concluded that application of organic amendments to agricultural soils is an eco-friendly strategy to improve soil conditions and non-target crop protection as well as the removal of herbicide residues from soil environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Triazine herbicides are one of the most widely used herbicide classes and play a major role in managing the weed populations in the agricultural production systems. These herbicides are valued because of their low costs, moderate persistence, and long season weed control in agroecosystems; however, the intensive utilization of these compounds may cause serious risks including environmental safety, water sources’ pollution (Martinez et al. 2016; Guillon et al. 2018; Montiel-León et al. 2019) as well as human, animal, and crop health (Ahsan and Del-Valls 2011; Baranowska et al. 2006; Kroon et al. 2014; Husak et al. 2016; Mehdizadeh and Gholami Abadan, 2018; Mehdizadeh, 2019). Haarstad and Ludvigsen (2007) analyzed the groundwater next to agricultural fields and found high quantities of metribuzin herbicide. It was reported that there is a significant relationship between application of this class of herbicides and cytotoxicity as well as breast cancer (Kettles et al. 1997; Huang et al. 2014). Every year in so many countries excessive amounts of soil-applied herbicides are used in agricultural lands; therefore, it seems that the need to provide safe and effective methods for herbicides removal and degradation from environment are very crucial. Nowadays, biological degradation is an important environmentally friendly strategy for detoxification and dissipation of herbicides from environment (Zhang and Quiao 2002). Metribuzin is a soil-applied highly water-soluble herbicide for the control of many broad-leaved and grass weeds in soya beans, sugar cane, and cereals (Tomlin 2000; Henriksen et al. 2002). Microbial degradation is the main pathway for metribuzin degradation from soil environment (Boreen et al. 2003; Lin and Reinhard 2005). Risk assessment of triazine herbicides needs to estimate their potential for persistence in environment considering soil components. However, among soil characteristics, organic matter content is a key factor that has important effect on herbicide degradation and movement in the soil (Moorman et al. 2001; Gamiz et al. 2017). Application of organic-based fertilizers can improve edaphic qualities and change the fate of any herbicide (Majumdar and Singh 2007; Marín-Benito et al. 2019). However, determining the behavior of herbicides in soil amended with non-chemical fertilizers is difficult. Some researchers reported that the application of organic-based fertilizers under different situations increases the herbicide degradation and movement in soil and under other conditions may decrease them (Singh 2008; Fernandez-Bayo et al. 2009; Kravvariti et al. 2010). The effects of non-chemical fertilizers on removal and sorption of pesticides have been extensively studied and different results have been reported. Some researchers found that the application of soil organic amendments could increase the persistence of herbicides by increasing the sorption process (Barker and Bryson 2002; Wanner et al. 2005). Different studies showed that the addition of organic matter including manures, composts, and plant residues to soils is a widely accepted non-chemical approach for improving the soil characteristics as well as the different crop production (Garcia-Gomez et al. 2002; Perez-Murcia et al. 2006; Bastida et al. 2008; Mehdizadeh et al. 2013; Pampuro et al. 2017a). Cox et al. (2000) concluded that the infertile soils had a minimum effect on herbicide movement; therefore, the presence of organic matter can be considered as an important adsorbent for herbicides.

Recently, the modification of fields’ soil by non-chemical fertilizers and its effects on herbicide’s fate in environment was considered to manage the environmental pollutions due to pesticide application in agroecosystems. However, the influence of different soil organic amendments on herbicide’s fate is very complicated (Briceno et al. 2007). Depending on the type of amendments and chemical structure of applied herbicide, the persistence and dissipation responses of these chemicals can be different (Umar et al. 2012). The sorption of triazine herbicides in soils incorporated with plant residues such as olive oil can be increased (Cabrera et al. 2008). Whereas Fuscaldo et al. (1999) found the higher persistence of atrazine, metribuzin, and simazine in non-amended soil. Different bioassay and analytical methods have been considered for the detection of triazine herbicides from soil environment, including plant bioassay (Fuscaldo et al. 1999), thin-layer chromatography (Johnson and Pepperman 1995), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Lawrence et al. 1993; Papadakis and Papadopoulou 2002; Sondhia and Singh 2018; Janaki et al. 2018) or mass spectrometry detection (Henriksen et al. 2002). The objective of this work was to study the influence of municipal waste compost and sheep manure on the fate and half-life of metribuzin using high-performance liquid chromatography and assess the carryover effect on oilseed rape using a bioassay method.

Materials and methods

Degradation study

To evaluate the degradation and persistence of metribuzin along with the application of two different soil organic amendments, experiments under controlled conditions were conducted during 2012–2014.

Amendments and soil

A silty loam soil from an unplanted field with no history of metribuzin application was chosen. Municipal waste compost (MC) and sheep manure (SM) were locally purchased. Soil and two amendment characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Chemicals

Two Bayer company (Germany) production of metribuzin including a commercial grade (Sencor® 70% w/w) and a technical grade active ingredient (99.8% purity) was used during experiments. Methanol and other chemicals were of analytical grade and obtained from Merck Company (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Preparation of soil samples

Soil (1000 g) was taken from the topsoil layer (0–15 cm) of unplanted soil, dried at 25–30 °C and homogenized by passing through a standard sieve (2 mm mesh) and separately amended with MC and SM in 2.5 percent rate (w/w). Commercial grade of metribuzin at the rate of 5 mg kg−1 soil was applied to soil samples and let to be balanced for 24 h at 4 °C. The moisture content of soil samples was regulated at 70% field capacity level and samples were incubated for a 120 day period in dark condition at room temperature (Fuscaldo et al. 1999). Metribuzin extraction was performed by taking 20 g of subsamples at 1, 5, 15, 30, 50, 90, and 120 days after herbicide application and kept at − 20 °C before analysis by HPLC (Shah et al. 2011). The next step was two times extraction of samples by adding 20 ml methanol and shaking for 90 min. Then the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. After stabilization of tube contents, 10 ml of supernatant was removed and concentrated on a rotary evaporator at 39 °C for obtaining solvent-free extracts. The final step was dilution of extracts by adding 5 ml analytical-grade methanol and kept the extracts at 5 °C until injection to HPLC.

Analytical procedure

Metribuzin analysis performed by a HPLC (Shimadzu model 10A, Japan) prepared with proper equipment including an integrated degasser, a quaternary pump to deliver methanol/water (80:20 v/v) as mobile phase at flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1, and an ultraviolet detector with selected wavelengths of 290 nm according to the UV spectra of the herbicide. The reversed-phase column was a 250 × 4.6 mm i.d. Adsorbosphere C18 and the injection volume was 20 µL. Known concentrations of metribuzin range 5.0–0.1 mg L−1 was provided in analytical-grade methanol and injected to HPLC and the peak area was calculated. The residual quantities of metribuzin were determined by comparing the peak area of extracts with calibrated standards. Dissipation of metribuzin in soil was confirmed to follow the first-order kinetics. The degradation rate of metribuzin was measured from the following equation:

where C is the residual concentration of metribuzin (mg kg−1 soil), k is the degradation rate constant, t is time and Ci is the initial concentration of herbicide (mg kg−1 soil) (Maheswari and Ramesh 2007; Mehdizadeh et al. 2017). DT50 and DT90 of metribuzin were calculated from the following equations:

where DT50 and DT90 denote the time required for 50% and 90% degradation of herbicide, respectively.

Bioassay study

Bioassay experiments were conducted to study the determination of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) sensitivity to metribuzin at different concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1 mg kg−1 soil) applied to the soil incorporated with MC and SM amendments. Soil samples were collected from a field with no history of triazine herbicide application and amended with MC and SM in 2.5 percent rate (w/w). Each concentration of herbicide was separately sprayed and thoroughly mixed with soil samples. Then 15 cm diameter plastic pots were filled with a modified soil with four replications for each concentration. Ten oilseed rape seeds were distributed uniformly in five regular positions on the surface soil and they were thinned to five seedlings per pot after germination (Mehdizadeh et al. 2016). The pots were kept under controlled environmental conditions, and shoot and root were harvested 4 weeks after emergence, and dry weights were measured.

Equation 4 is a log-logistic model that represents plant response of root and shoot dry weights per pot (Y) as a function of metribuzin doses, x. Data were analyzed by R software using drc package:

In this model d parameter is the upper asymptote (maximum biomass per pot), b denotes the slope of the curve around the ED50, which denotes the dose that inflicts a 50% biomass reduction relative to d. The log-logistic model fitted well to the plant response for metribuzin. The ED10 and ED90 were calculated on the original fit.

Results and discussion

Degradation study

Decomposition of herbicide slowly occurred. This confirmed that the complete degradation of 5 mg kg−1 metribuzin in controlled conditions requires more than 120 days. First-order kinetics model provided an excellent fit with the degradation of metribuzin affected by MC and SM application with large regression coefficient (R2 ≥ 0.96). The same results were reported by previous researchers (Henriksen et al. 2004; Maqueda et al. 2009). Metribuzin standard residues in the soil treatments were measured by applying a seven-point calibration graph (0.1–5 mg kg−1 soil). As shown in Fig. 1, this method presented a proper fitting line for metribuzin standard data (R2 > 0.99). The peak results of HPLC analysis of metribuzin standard are presented in Table 3. Metribuzin residues in amended soils were degraded increasingly over time. Nonetheless, the intensity of degradation depended on the nature of organic amendment. After 120 days (the end of experiments), only 11.2% and 27.8% of metribuzin residues remained in soil amended with MC and SM, respectively. However, 40.2% of residues remained in the non-amended soil. Degradation constant (K) and DT values are shown in Table 4.

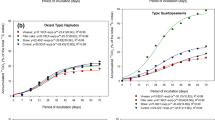

MC and SM soil amendments showed variation in the dissipation rate of metribuzin during incubation times. During the first few days after herbicide treatment, metribuzin residues decreased at the same rates in the non-amended and amended soils (Fig. 2). Results showed that degradation rate for the first 15 days after soil treatment with mitribuzin were not significantly different between non-amended and soil amended with MC and SM (P = 0.05). After 15 days of incubation, comparison of MC, SM, and non-amended soil effect on metribuzin degradation showed significant differences. After the final incubation time, metribuzin was not completely removed from soil samples in all treatments; it confirmed that complete removal of metribuzin under the conditions of this experiment needs a time more than 4 months. Half-life more than 1 year for metribuzin and its primary metabolites in subsoil was reported (Henriksen et al. 2004). Degradation of metribuzin in 24 different soils was investigated by Juhler et al. (2008). They reported that in soils with higher organic matter content, the removal of herbicide was faster than soils with organic matter content. Organic amendments have great sources of N, C, and other nutritional elements that can be assumed as proper conditions for living organisms in the soil. As presented in Table 1, MC and SM had high level of nutrients and enhanced degradation of metribuzin in these treatments was expected. Drenovsky and Richards (2005) found that soils amended with organic fertilizers had a higher quantity and activity of microorganisms. Metribuzin degradation rate had a proper correlation with carbon–nitrogen ratio in applied organic amendments. This ratio for MC (15.42) was lower than SM (19). Therefore, municipal waste compost had the most effect on the metribuzin dissipation and probably had a greater impact on dynamics of soil microbial communities leading to increased herbicide degradation. Previous studies have shown that atrazine biodegradation was significantly affected by application of different organic manures (Kadian et al. 2008; Sadegh-Zadeh et al. 2017). Cox et al. (2001) reported that organic matter addition to soil increased pesticide biodegradation. Except for abiotic degradation, one of the most important pathways for degradation of metribuzin in soil environment is biodegradation due to existence of different groups of microorganisms (Henriksen et al. 2004; Benoit et al. 2007). Therefore, soil organic matter substances had a facilitator role on removal of herbicides from agricultural fields. Kah and Brown (2007) found a direct correlation between metribuzin degradation and soil characteristics including organic C content as well as the C/N ratio. Vinther et al. (2008) concluded that both biotic and non-biotic degradation of metribuzin in soil environment was intensively affected by level of organic matter in the soil. Many studies reported that the addition of organic amendments can also accelerate or enhance herbicide biodegradation by stimulating microbial growth in different soils (Sanchez et al. 2004; Agamuthu et al. 2013; Herrero-Hernández et al. 2015).

On the contrary to our findings, Dolaptsoglou et al. (2007) reported that the soil application of municipal waste, composted poultry manure and plant residues of corn field reduced the degradation of terbuthylazine. Koner et al. (2012) reported that application of silica gel waste increased the removal of 2,4-D herbicide from agricultural wastewater via adsorbing the herbicide molecules. Whereas, other studies have reported that organic matter amendment has no effect on pesticide dissipation. Soil dissipation of glyphosate herbicide was not affected by application of compost to the soil (Getenga and Kengara 2004). However, in his earlier study Getenga (2003) found that compost added to the same soil increased atrazine degradation. These differences may be due to the nature of herbicides, type of organic amendments, and different properties of experimental soils.

Half-lives and DT90 values of metribuzin in amended soils were significantly lower than non-amended soil (P ≤ 0.01) which indicates that the soil microbial population had a key role in metribuzin dissipation. Previous studies also reported that microbial degradation was a major pathway for metribuzin removal from agroecosystems (Benoit et al. 2007; Maqueda et al. 2009). The half-life of herbicide in non-amended soil was 119.48 days. However, this value was 87.72 and 103.43 days in the MC and SM application, respectively (Table 4). Among all treatments, MC was most effective on removal of metribuzin in silty loam soil. On the contrary to our half-life results, other researchers reported lower half-lives (11–46 days) for soil dissipation of metribuzin in different conditions (Lechon et al. 1997; Di et al. 1998). Nevertheless, higher than 145 days also have been reported for metribuzin half-life in the soil (Webb and Aylmore 2002). Moorman et al. (2001) found that removal of metribuzin in soil amended by different organic fertilizers was faster than non-amended soils. However different results have been reported by Lopez-Pineiro et al. (2012). They found that application of olive oil extraction residues significantly increased the half-life of terbuthylazine residues in agricultural soil.

Bioassay study

The responses of oilseed rape root and shoot biomass were well described by logistic model with acceptable limits for metribuzin. The model parameter estimates are shown in Table 5. Oilseed rape was susceptible to metribuzin soil residues in all concentrations and plant biomass was significantly reduced. As shown in Table 5, the root biomass was more susceptible than shoot biomass, where the EDs were smaller for root than for shoot biomass. Also the application of organic amendments has led to increased oilseed rape tolerance to metribuzin residues in soil, since the required metribuzin doses for 10, 50, and 90% biomass reduction of oilseed rape in the soil amended with MC and SM were more than that for non-amended soil (Table 5). This could be due to the direct impacts of organic amendments on improving the growth components of oilseed rape (Nkoa et al. 2014) and on the other hand, the effect of these amendments on degradation of metribuzin in soil. MC had the most impact on enhancement of oilseed rape tolerance to herbicide residues in the soil (Figs. 3, 4). As reported in the degradation study, application of MC amendment had the most impact on metribuzin degradation compared to other treatments. Triazine herbicides have high to moderate persistence in soil environment (Mercurio et al. 2015). This tends to be a great risk deal to their phytotoxic effects on susceptible crops in rotation.

Selecting a suitable herbicide to use, and planting a resistant or tolerant species in rotation is very important in agricultural management. More information about the sensitivity of plant species to herbicides can give us some managerial perspectives to handle the negative side effects of herbicide residues. By knowing the level of metribuzin residues in the soil and the effect on particularly sensitive crops, agricultural managers can apply the necessary considerations about crop rotations if sensitive crop such as oilseed rape is supposed to be planted in the field that was previously treated with triazine herbicides. The present study revealed that metribuzin residues at concentrations higher than 0.2 mg kg−1 soil had an irretrievable effect on oilseed rape; however, the application of MC and SM has led to a decrease in the susceptibility of this plant to metribuzin residues in the soil.

Conclusion

Based on the obtained results, it can be concluded that application of organic amendments enhanced the degradation of metribuzin and reduced the toxicity effects of its residues on oilseed rape. The higher dissipation of metribuzin by adding amendments to soil indicates that the soil microorganisms are able to remove metribuzin from agricultural soils and this practice can be considered in improving conventional agricultural management. The fact that there are microorganisms that are able to metabolize metribuzin in field soil, and organic amendments such as compost and manure may stimulate their activity, suggests that it may be possible to influence the fate and degradation of metribuzin and other chemicals applied to soil, but are difficult to adopt on large surfaces because the difficulties, and the costs to transport the product from the area where it is available to those where it can be applied to soil and the difficulties in application itself (Pampuro et al. 2017b). An additional obstacle to adoption of organic amendments is the farmers’ knowledge and awareness about the effects of such products in improving biological characteristics of soil (Pampuro et al. 2018). The present study suggests that application of non-chemical amendments can lead to faster removal of metribuzin in soil environment. However, conducting more studies under different situations seems to be necessary. Application of residual herbicides such as metribuzin can impose many harmful effects on the environment; therefore, the application of organic amendments can be considered as an eco-friendly strategy for management of the pesticide residues in environment.

References

Agamuthu P, Tan YS, Fauziah SH (2013) Bioremediation of hydrocarbon contaminated soil using selected organic wastes. Proc Environ Sci 18:694–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2013.04.094

Ahsan DA, Del-Valls TA (2011) Impact of arsenic contaminated irrigation water in food chain: an overview from Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res 5:627–638. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijer.2011.370

Baranowska I, Barchanska H, Pacak E (2006) Procedures of trophic chain samples preparation for determination of triazines by HPLC and metals by ICP-AES methods. Environ Pollut 143:206–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2005.11.039

Barker AV, Bryson GM (2002) Bioremediation of heavy metals and organic toxicants by composting. Sci World J 2:407–420. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2002.91

Bastida F, Kabdeler E, Moreno JL, Ros M, Garcia C, Hernandez T (2008) Application of fresh and composted organic wastes modifies structure, size and activity of soil microbial community under semiarid climate. Appl Soil Ecol 40:318–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2008.05.007

Benoit P, Perceval J, Stenrod M, Moni C, Eklo OM, Barriuso E, Sveistrup T (2007) Availability and biodegradation of metribuzin in alluvial soils as affected by temperature and soil properties. Eur Weed Res 47:517–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3180.2007.00589.x

Boreen AL, Arnold WA, McNeill K (2003) Photodegradation of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment: a review. Aquat Sci 65:320–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-003-0672-7

Briceno G, Palma G, Duran N (2007) Influence of organic amendment on the biodegradation and movement of pesticides. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 37:233–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643380600987406

Cabrera A, Cox L, Koskinen W, Sadowsky M (2008) Availability of triazine herbicides in aged soils amended with olive oil mill waste. J Agric Food Chem 56:4112–4119. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf800095t

Cox L, Celis R, Hermosin MC, Cornejo J, Zsolnay A, Zeller K (2000) Effect of organic amendments on herbicide sorption as related to the nature of the dissolved organic matter. Environ Sci Technol 34:4600–4605. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0000293

Cox L, Cecchi A, Celis R, Hermosin MD, Koskinen WC, Cornejo J (2001) Effect of exogenous carbon on movement of simazine and 2, 4-D in soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 65:1688–1695. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2001.1688

Di HJ, Aylmore LA, Kookana RS (1998) Degradation rates of eight pesticides in surface and subsurface soils under laboratory and field conditions. Soil Sci 163:404–411. https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-199805000-00008

Dolaptsoglou C, Karpouzas DG, Menkissoglu-Spiroudi U, Eleftherohorinos I, Voudrias EA (2007) Influence of different organic amendments on the degradation, metabolism, and adsorption of terbuthylazine. J Environ Qual 36:1793–1802. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2006.0388

Drenovsky RE, Richards JH (2005) Nitrogen addition increases fecundity in the desert shrub Sarcobatus vermiculatus. Oecologia 143:349–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1821-y

Fernandez-Bayo JD, Nogales R, Romero E (2009) Assessment of three vermicomposts as organic amendments used to enhance diuron sorption in soils with low organic carbon content. Eur J Soil Sci 60:935–944. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2009.01176.x

Fuscaldo F, Bedmr F, Monterubbianesi G (1999) Persistence of atrazine, metribuzin and simazine herbicides in two soils. Pesq Agropec Bras 34:2037–2044. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X1999001100009

Gamiz B, Velarde P, Spokas KA, Hermosin MC, Cox L (2017) Biochar soil additions affect herbicide fate: importance of application timing and feedstock species. J Agric Food Chem 63:3109–3117. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.7b00458

Garcia-Gomez A, Bernal MP, Roig A (2002) Growth of ornamental plants in two composts prepared from agroindustrial wastes. Bioresour Technol 83:81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00211-5

Getenga ZM (2003) Enhanced mineralization of atrazine in compost-amended soil in laboratory studies. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 71:933–941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-001-8952-4

Getenga ZM, Kengara FO (2004) Mineralization of glyphosate in compost-amended soil under controlled conditions. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 72:266–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-003-9004-9

Guillon A, Videloup C, Leroux C, Bertin H, Philibert M, Baudin I, Bruchet A, Esperanza M (2018) Occurrence and fate of 27 triazines and metabolites within French drinking water treatment plants. Water Supply 19:463–471. https://doi.org/10.2166/ws.2018.091

Haarstad K, Ludvigsen GH (2007) Ten years of pesticide monitoring in Norwegian ground water. Groundwater Monit Remediat 27:75–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6592.2007.00153.x

Henriksen T, Svensmark B, Juhler RK (2002) Analysis of Metribuzin and transformation products in soil by pressurized liquid extraction and liquid chromatographic–tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 957:79–87

Henriksen T, Svensmark B, Juhler RK (2004) Degradation and sorption of metribuzin and primary metabolites in a sandy soil. J Environ Qual 33:619–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(01)01453-4

Herrero-Hernández E, Marín-Benito JM, Andrades MS, Sánchez-Martín MJ, Rodríguez-Cruz MS (2015) Field versus laboratory experiments to evaluate the fate of azoxystrobin in an amended vineyard soil. J Environ Manag 163:78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.08.010

Huang P, Yang J, Song Q (2014) Atrazine affects phosphoprotein and protein expression in MCF-10A human breast epithelial cells. Int J Mol Sci 15:17806–17826. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms151017806

Husak VV, Mosiichuk NM, Maksymiv IV, Storey JM, Storey KB, Lushchak VI (2016) Oxidative stress responses in gills of goldfish, Carassius auratus, exposed to the metribuzin-containing herbicide Sencor. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 45:163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2016.05.028

Janaki P, Bhuvanadevi S, Dhananivetha M, Murali-Arthanari P, Chinnusamy C (2018) Persistence of quizalofop ethyl in soil and safety to ground nut by ultrasonic bath extraction and HPLCDAD detection. J Res Weed Sci 1:63–74. https://doi.org/10.26655/jrweedsci.2018.9.1

Johnson RM, Pepperman AB (1995) Analysis of metribuzin and associated metabolites in soil and water samples by solid-phase extraction and reversed-phase thin-layer chromatography. J Liq Chromatogr 18:739–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826079508009269

Juhler RK, Henriksen T, Ernstsen V (2008) Impact of basic soil parameters on pesticide disappearance investigated by multivariate partial least square regression and statistics. J Environ Qual 37:1719–1732. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2006.0230

Kadian N, Gupta A, Satya S, Kumari R, Malik A (2008) Biodegradation of herbicide atrazine in contaminated soil using various bioprocessed materials. Biores Technol 99:4642–4647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.06.064

Kah M, Brown CD (2007) Prediction of the adsorption of ionizable pesticides in soils. J Agric Food Chem 55:2312–2322. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf063048q

Kettles MK, Browning SR, Prince TS, Horstman SW (1997) Triazine herbicide exposure and breast cancer incidence: an ecologic study of Kentucky countries. Environ Health Perspect 105:1222–1227. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.971051222

Koner S, Pal A, Adak A (2012) Use of surface modified silica gel factory waste for removal of 2,4-D pesticide from agricultural wastewater: a case study. Int J Environ Res 6:995–1006. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijer.2012.570

Kravvariti K, Tsiropoulos NG, Karpouzas DG (2010) Degradation and adsorption of terbuthylazine and chlorpyrifos in biobed biomixtures from composted cotton crop residues. Pest Manag Sci 66:1122–1128. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.1990

Kroon FJ, Hook SE, Jones D, Metcalfe S, Osborn HL (2014) Effects of atrazine on endocrinology and physiology in juvenile barramundi, Lates calcarifer (Bloch). Environ Toxicol Chem 33:1607–1614. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2594

Lawrence JR, Eldam M, Sonzogni WC (1993) Metribuzin and metabolites in Wisconsin (USA) well water. Water Res 27:1263–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1354(93)90212-Z

Lechon Y, Garcia-Valcarcel AI, Matienzo T, Sanchez-Brunete C, Tadeo JL (1997) Laboratory and field studies on metribuzin persistence in soil and its prediction by simulation models. Toxicol Environ Chem 63:47–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/02772249709358516

Lin AYC, Reinhard M (2005) Photodegradation of common environmental pharmaceuticals and estrogens in river water. Environ Toxicol Chem 24:1303–1309. https://doi.org/10.1897/04-236R.1

Lopez-Pineiro A, Albarran A, Cabrera D, Pena D, Becerra D (2012) Environmental fate of terbuthylazine in soils amended with fresh and aged final residue of the olive-oil extraction process. Int J Environ Res 6:933–944. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijer.2012.564

Maheswari ST, Ramesh A (2007) Adsorption and degradation of sulfosulfuron in soils. Environ Monit Assess 127:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-006-9263-0

Majumdar K, Singh N (2007) Effect of soil amendments on sorption and mobility of metribuzin in soils. Chemosphere 66:630–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.07.095

Maqueda C, Villaverde J, Sopena F, Undabeytia S, Morillo S (2009) Effects of soil characteristics on metribuzin dissipation using clay-gel-based formulations. Agric Food Chem 57:3273–3278. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf803819q

Marín-Benito JM, Carpio MJ, Sánchez-Martín MJ, Rodríguez-Cruz MS (2019) Previous degradation study of two herbicides to simulate their fate in a sandy loam soil: effect of the temperature and the organic amendments. Sci Total Environ 635:1301–1310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.015

Martinez S, Delgado M, Jarvis P, Tobeh A (2016) Removal of Herbicide Mecoprop from surface water using advanced oxidation processes (AOPS). Int J Environ Res 10:291–296

Mehdizadeh M (2019) Sensitivity of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) to soil residues of imazethapyr herbicide. Int J Agric Environ Food Sci 3:46–49. https://doi.org/10.31015/jaefs.2019.1.10

Mehdizadeh M, Gholami Abadan F (2018) Negative effects of residual herbicides on sensitive crops: impact of rimsulfuron herbicide soil residue on sugar beet. J Res Weed Sc 1:1–6. https://doi.org/10.26655/jrweedsci.2018.6.1

Mehdizadeh M, Izadi-Darbandi E, Naseri-Rad H, Tobeh A (2013) Growth and yield of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) as influenced by different organic fertilizers. Int J Agron Plant Prod 4:734–738

Mehdizadeh M, Alebrahim MT, Roushani M, Streibig JC (2016) Evaluation of four different crops’ sensitivity to sulfosulfuron and tribenuron methyl soil residues. Acta Agric Scand B Soil Plant Sci 66:706–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2016.1212919

Mehdizadeh M, Alebrahim MT, Roushani M (2017) Determination of two sulfonylurea herbicides residues in soil environment using HPLC and phytotoxicity of these herbicides by lentil bioassay. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 99:93–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-017-2076-8

Mercurio P, Mueller JF, Eaglesham G, Flores F, Negri AP (2015) Herbicide persistence in seawater simulation experiments. PLoS One 10:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136391

Montiel-León JM, Vo Duy S, Munoz G, Bouchard MF, Amyot M, Sauvé S (2019) Quality survey and spatiotemporal variations of atrazine and desethylatrazine in drinking water in Quebec, Canada. Sci Total Environ 671:578–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.228

Moorman TB, Cowan JK, Arthur EL, Coats JR (2001) Organic amendments to enhance herbicide biodegradation in contaminated soils. Biol Fertil Soils 33:541–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003740100367

Nkoa R, Ondoua B, Voroney P, Tambong J (2014) Evidence of the interaction between crop species and organic amendments: modelling of the differential grain yield response of wheat, soybean, and canola to organic amendments. Sustain Agric Res 3:33–45. https://doi.org/10.5539/sar.v3n4p33

Pampuro N, Bertora C, Sacco D, Dinuccio E, Grignani C, Balsari P, Cavallo E, Bernal MP (2017a) Fertilizer value and greenhouse gas emissions from solid fraction pig slurry compost pellets. J Agric Sci 155:1646–1658. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002185961700079X

Pampuro N, Bagagiolo G, Priarone PC, Cavallo E (2017b) Effects of pelletizing pressure and the addition of woody bulking agents on the physical and mechanical properties of pellets made from composted pig solid fraction. Powder Technol 311:112–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2017.01.092

Pampuro N, Caffaro F, Cavallo E (2018) Reuse of animal manure: a case study on stakeholders’ perceptions about pelletized compost in Northwestern Italy. Sustainability 10:2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062028

Papadakis EN, Papadopoulou E (2002) Determination of metribuzin and major conversion products in soils by microwave-assisted water extraction followed by liquid chromatographic analysis of extracts. J Chromatogr A 962:9–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00537-X

Perez-Murcia MD, Moral R, Moreno-Caselles J, Perez-Espinosa A, Paredes C (2006) Use of composted sewage sludge in growth media for broccoli. Bioresour Technol 97:123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.005

Sadegh-Zadeh f, Abd-Wahid S, Jalili B (2017) Sorption, degradation and leaching of pesticides in soils amended with organic matter: a review. Adv Environ Technol 2:119–132. https://doi.org/10.22104/AET.2017.1740.1100

Sanchez ME, Estrada IB, Martinez O, Martin-Villacorta J, Aller A, Moran A (2004) Influence of the application of sewage sludge on the degradation of pesticides in the soil. Chemosphere 57:673–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.07.023

Shah J, Rasul Jan M, Ara B, Shehzad FN (2011) Quantification of triazine herbicides in soil by microwave-assisted extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography. Environ Monit Assess 178:111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-010-1676-0

Singh N (2008) Biocompost from sugar distillery effluent: effect on metribuzin degradation, sorption and mobility. Pest Manag Sci 64:1057–1062. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.1598

Sondhia S, Singh PK (2018) ioefficacy and fate of pendimethalin residues in soil and mature plants in chickpea field. J Res Weed Sci 1:28–339. https://doi.org/10.26655/jrweedsci.2018.6.4

Tomlin CDS (2000) The pesticide manual, 12th edn. British Crop Protection Council, Farnham

Umar AF, Tahir F, Larkim M, Oyawoye OM, Musa BL, Yerima MB, Agbo EB (2012) In-situ biostimulatory effect of selected organic wastes on bacterial atrazine biodegradation. Adv Microbiol 2:587–592. https://doi.org/10.4236/aim.2012.24076

Vinther FP, Brinch UC, Elsgaard L, Fredslund L, Iversen BV, Torp S, Jacobsen CS (2008) Field-scale variation in microbial activity and soil properties in relation to mineralization and sorption of pesticides in a sandy soil. J Environ Qual 37:1710–1718. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2006.0201

Wanner U, Fuhr F, Burauel P (2005) Influence of the amendment of corn straw on the degradation behaviour of the fungicide dithianon in soil. Environ Pollut 133:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2004.04.013

Webb KM, Aylmore LAG (2002) The role of soil organic matter and water potential in determining pesticide degradation. Dev Soil Sci 28:117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2481(02)80048-4

Zhang J, Quiao C (2002) Novel approaches for remediation of pesticide pollutants. Int J Environ Pollut 18:423–433. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEP.2002.002337

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehdizadeh, M., Izadi-Darbandi, E., Naseri Pour Yazdi, M.T. et al. Impacts of different organic amendments on soil degradation and phytotoxicity of metribuzin. Int J Recycl Org Waste Agricult 8 (Suppl 1), 113–121 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-019-0280-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-019-0280-8