Abstract

Intensification of CaCO3 nanoparticle production process through RPB is investigated in this work. More controllability attainment for a process is one of the objectives in the process intensification. Therefore, the study of the affecting factors on quality and quantity of the produced nanoparticles is very important. The suitable device was designed and manufactured for CO2 and Ca(OH)2 reaction and crystallization in the nanoparticle form. The effect of packing type, rotating speed, gas and liquid flowrates was studied on the reaction time, the precipitation amount and the particle size in the liquid phase, according to the analysis of experiments designed based on the standard method. The results showed that the obtained particles in the system equipped with the Saddle type packing have smaller size compared to the system equipped with Pall type one. A theoretical model has been proposed to estimate the intermediate species, supersaturation, induction time and theoretical precipitation amount. The model implies that pH 11.4 is the best condition to have higher product rate. In addition, a new residence time distribution model for the recycled systems is proposed and experimentally evaluated for the setup.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term of “process intensification” is referred to special improvements of different processes regarding the process flexibility, product quality, speed to market and inherent safety in order to reach smaller equipment, higher efficiency or less environmental problems. Higee, in which gravity is replaced by a centrifugal force, is categorized as a process intensification that has been used in various processes such as distillation, chemical reactions and nanoparticle production. The height of transfer unit of the RPB is low and the efficiency of mass transfer and micromixing can be up to 1–3 orders of magnitude larger than that in a conventional packed bed, exhibiting prominent process intensification characteristics [1, 2]. Different geometry and improvements on rotating reactor have been reported [3]. Nano-fibers of aluminum hydroxide, TiO2, silver, CuO, magnesium carbonate, ZnO, Fe3O4 and drug nanoparticles are some of the nanoparticles produced by Higee [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Uniform, small particles were produced in the RPB due to the presence of a sharp supersaturation interface accompanied by the very short liquid residence time in the device [14]. Also, it is expected to have more control over the product quality and quantity through various adjustable factors of RPB as will be discussed in this work.

Calcium carbonate is used in the bioinspired composites, thermoplastics and rubbers to improve the modulus and heat stability, as a filler in the paper, etc. [15,16,17,18]. Calcium carbonate nanoparticles have been observed to be biocompatible for use in medicine, pharmaceutical industries, and drug delivery systems [19]. Various reactions can be applied for CaCO3 production including Na2CO3 + CaCl2, (NH2)2CO + CaCl2 with the assistance of MgCl2 or Ca(OH)2 + CO2 [14, 20, 21]. Synthesis of CaCO3 nanoparticles through the last reaction using RPB reactor has been investigated by some authors, especially Chen et al. [11, 13, 14, 22].

The effects of the radial thickness of packing, liquid flow rate and rotating speed on the product particle size were investigated for BaSO4 precipitation in RPB. The results indicated that the mean particle size of precipitates decreases with the increase of rotating speed and liquid flow rate [23]. Experiments using an RPB with blade packings and static baffles show that pressure drop increased as the gas flow rate and rotational speed increased and was not significantly affected by liquid flow rate. The mass transfer coefficient increased as gas flow rate, liquid flow rate, and rotational speed increased [24]. Calculation of RTD of RPB showed that it is equivalent to two mixed tanks in series and the related RTD varies with liquid flow rate and rotating speed nevertheless gas flow has no influence on liquid flow distribution [25]. The RTD analysis showed that the flow pattern became closer to plug flow with an increase of spinning speed and flow rate for an innovative enzymatic reaction intensification technology called the spinning cloth disc reactor (SCDR) [26]. Yang et al. studied mixing at the molecular scale (micromixing) using the diazo-coupling test reactions in a horizontal-axis RPB and iodide–iodate test reactions in a vertical-axis RPB. They defined segregation index (0 < XS < 1) where XS = 0 and XS = 1 indicate maximum micromixing and total segregation, respectively. They concluded that Xs decreases distinctly with increasing rotational speed but decreases slightly as the augment of flow rates and RPB has a distinct advantage in improving micromixing efficiency [27].

The study of reaction crystallization is more difficult than that of classical crystallization because the crystal generation depends on the chemical reaction, crystallization, and mixing, which all have their kinetics [28]. For example, the kinetics of crystallization of calcium carbonate was studied by following the changes in pH of solutions of CaCI2, NaHCO3 and NaOH in the presence of calcite seed crystals and 24 variables were determined using an iterative calculation procedure on the independent equations [29]. Recently, the kinetics of calcium carbonate crystallization have been studied in various fields [30,31,32,33].

Calcium carbonate is found naturally as the following polymorphs: aragonite (orthorhombic form), calcite (hexagonal crystal) and vaterite that the structure of calcite is the most common mineral. Aragonite is formed if precipitation is carried out at a temperature approaching the boiling point of water (higher than 85 ℃), whereas when precipitation is carried out at room temperature, only calcite is resulted. Vaterite is formed by precipitation at 60 ℃ [34]. Usually, high supersaturation favors the formation of vaterite and dendritic aragonite which is easily agglomerated to form a rosette particle morphology. On the other hand, calcite nucleates at mild supersaturation and moderate temperature as rhombohedron. However, the crystal forms of sparingly soluble salts produced by the primary mechanism are difficult to control. Operating conditions, such as solution composition, pH, temperature, additives and agitation speed, are important factors [35]. Among the various polymorphs, calcite is thermodynamically stable and can be synthesized with various morphologies: rhombohedral or cubic, scalenohedral or rosette and colloidal. The polymorph aragonite is metastable and has a needle-like or whisker shape morphology [36]. Throughout the whole temperature range of the diagram, calcite is stable, both aragonite and vaterite are metastable, and aragonite is more stable than vaterite [37].

In this work, an RPB for production of CaCO3 nanoparticles was manufactured based on the reaction of Ca(OH)2 and CO2 and the effect of various factors including packing type, rotating speed, gas and liquid flowrates was studied on various responses including reaction time, precipitation amount and particle size in the liquid phase. In addition, a simple kinetic model and also a suitable RTD model are proposed.

Experiments

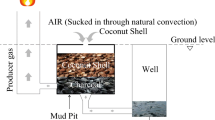

An experimental setup as depicted in Fig. 1 is used for the production of CaCO3 nanoparticles. The RPB reactor (Stainless steel 307) as shown in Fig. 2 consists of three sections including a (1) stationary part that is an SS-307 cover (length 100 mm and diameter 200 mm) with inlet and outlet of gas and liquid (each one is 1/8 in. pipe with length 100 mm); (2) a rotating part that rotates with a motor in the range of 3000–4000 rpm and consists of a grating form vessel (inner diameter 50 mm, outer diameter 150 mm) containing packings and (3) a distributer that is a pipe (length = 48 mm, width = 1 mm) with fine holes for spraying the feed. The extent of the reaction progress is measured by the pH (via a digital pH meter, AZ instrument, China, with the precision equal to 0.1) of the output solution from RPB. Every experiment was terminated at neutralization condition (pH about 7). The reaction time is measured by a chronometer with the precision of 0.01 s. The electrical conductivity (EC) to determinate RTD is measured using a conductivity pen (AZ instrument, China). The size of the particles in the final product was measured by the analysis of FESEM (Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy) figures as reported by the Nano Electronic laboratory of School of Electrical and Computer Engineering of the University of Tehran. The precipitation amount was weighted by a balance with the precision of 0.01 g. The applied packings were polypropylene Pall type and ceramic Saddle type.

The carbon dioxide gas was supplied with the 40 kg CO2 cylinder from Orsa Gas Co. with the purity of 98% and the applied Ca(OH)2 feed (4.5 L) was produced via mixing of lime (7.155 g CaO for 4.5 L feed from a local mine) and water in the continuously stirred feed tank (a polyethylene vessel with the dimensions of 40 × 40 × 15 cm) during the experiments. The required KCl (Potassium chloride) for RTD experiments is supplied from Dr. Mojallali industrial chemical complex, Iran.

Here with the assumption of the existence of curvature in the response surface, Box-Behnken Design (BBD) was selected to study the effect of three factors as: (1) rotating speed in the range of 3000–4000 rpm, (2) gas flow rate in the range of 3–5.5 L/min and (3) liquid flow rate in the range of 3–9 L/min on three responses including (1) reaction time (the time to reach pH 7), (2) precipitation amount and (3) particle size in the liquid phase. All experiments were done for Pall and Saddle type packings.

In a typical experiment, the affecting factors (motor speed, gas and liquid flowrates) were adjusted at prescribed values. The specified flow rate (measured by KSK—All-Plastic Low-Flow Flowmeter, KOBOLD, Germany) of the feed was pumped to the RPB via a pump (CS-0720B-CSE, Gear pump, Korea) through the distributer beside the injection of CO2 and recycled to the feed tank. During the reaction with the CO2, the suspension pH was reduced from about 13–7. The suspension pH values against time were read online and when the neutralization condition was reached, the precipitation amount was weighted and 250 mL of the liquid product was taken for FESEM analysis. The laboratory expert evaporates the water of 1 mL of the sample for FESEM analysis and gives us the range of nanoparticle size as reported in Tables 1 and 2.

The proposed model

Based on the inspiration from the work of Wiecher et al. [29], it is proposed that the following nine equations can be used to estimate the concentration of nine species that are probably the intermediates of the reaction Ca(OH)2 with CO2. The calculations are explicit unless in the case of activity factor for monovalent and divalent ions (fM and fD, respectively). The estimated concentrations are used to evaluate theoretical solid formation amount, induction time and supersaturation as will be explained in this section. The input data are pH at the specified time (measured by pH meter) and total calcium in the system (TCa equal to the moles of initial used CaO). The values of fM and fD depend on the species concentration; therefore, the guessed value at the beginning of the calculations is unity and optimized to converge at a fixed value with an accepted error. The sequence of calculations for nine species is as follows:

-

1.

Calculate the concentration of H+

$$ \left[ {{\text{H}}^{ + } } \right] = \frac{{10^{\text{ - pH}} }}{{f_{M} }} $$(1) -

2.

Calculate the concentration of HO−

$$ \left[ {{\text{HO}}^{ - } } \right] = \frac{{K_{w} }}{{\left[ {{\text{H}}^{ + } } \right]f_{M}^{2} }} $$(2) -

3.

Calculate the concentration of HCO3− and

-

4.

Ca2+ from a set of two equations derived using the conservation of total calcium and neutrality conditions as

$$ \left\{ \begin{aligned} \left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right] = \frac{{T_{\text{Ca}} }}{{1 + \frac{{K_{2} f_{D} }}{{K_{{{\text{CaCO}}_{3} }} \left[ {{\text{H}}^{ + } } \right]}}\left[ {{\text{HCO}}_{3}^{ - } } \right] + \frac{{f_{D} \left[ {{\text{HCO}}_{3}^{ - } } \right]}}{{K_{{{\text{CaHCO}}_{3} }} }} + \frac{{f_{D} \left[ {{\text{HO}}^{ - } } \right]}}{{K_{\text{CaOH}} }}}} \hfill \\ \left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right]\left[ {{\text{HCO}}_{3}^{ - } } \right]\frac{{f_{D} }}{{K_{{{\text{CaHCO}}_{3} }} }} + 2\left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right] + \left[ {{\text{H}}^{ + } } \right] + \left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right]\frac{{f_{D} \left[ {{\text{HO}}^{ - } } \right]}}{{K_{\text{CaOH}} }} - 2\frac{{k_{2} f_{D} }}{{\left[ {{\text{H}}^{ + } } \right]}}\left[ {{\text{HCO}}_{3}^{ - } } \right] \hfill \\ \begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} & {} & {} \\ \end{array} - \left[ {{\text{HCO}}_{3}^{ - } } \right] - \left[ {{\text{HO}}^{ - } } \right] = 0 \hfill \\ \end{aligned} \right. $$(3,4) -

5.

Calculate the concentration of CaOH+

$$ \left[ {{\text{CaOH}}^{ + } } \right] = \frac{{f_{D} }}{{K_{\text{CaOH}} }}\left[ {{\text{HO}}^{ - } } \right]\left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right] $$(5) -

6.

Calculate the concentration of H2CO3

$$ \left[ {{\text{H}}_{2} {\text{CO}}_{3} } \right] = \frac{{f_{M}^{2} }}{{K_{1} }}\left[ {{\text{H}}^{ + } } \right]\left[ {{\text{HCO}}_{3}^{ - } } \right] $$(6) -

7.

Calculate the concentration of CaCO3

$$ \left[ {{\text{CaCO}}_{3} } \right] = \frac{{K_{2} f_{D} }}{{K_{{{\text{CaCO}}_{3} }} }}\frac{{\left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right]\left[ {{\text{HCO}}_{3}^{ - } } \right]}}{{\left[ {{\text{H}}^{ + } } \right]}} $$(7) -

8.

Calculate the concentration of CaHCO3+

$$ \left[ {{\text{CaHCO}}_{3}^{ + } } \right] = \frac{{K_{{{\text{CaCO}}_{3} }} }}{{K_{{{\text{CaHCO}}_{3} }} K_{2} }}\left[ {{\text{H}}^{ + } } \right]\left[ {{\text{CaCO}}_{3} } \right] = \frac{{f_{D} }}{{K_{{{\text{CaHCO}}_{3} }} }}\left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right]\left[ {{\text{HCO}}_{3}^{ - } } \right] $$(8) -

9.

Calculate the concentration of CO32−

where the K values are taken as thermodynamic equilibrium constants as follows:

and T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin. The ionic strength of solution is defined as:

and activity factor for monovalent and divalent ions derived through

where \( F\left( I \right) = I\left( {\frac{\sqrt I }{1 + \sqrt I } - 0.3I} \right) \). The corrected fM and fD are used to recalculate the concentration of nine species and this work is repeated to have stationary values. Here, the following relation is checked to have stationary values

The solubility of calcite, aragonite and vaterite in CO2–H2O solutions between 0 and 90 °C has been correlated [38]. Here, the solubility product proposed by Langmuir is used [29].

where \( - \log \left( {K_{\text{sp}} } \right) = 0.01183T + 8.03 \) and T in this equation is temperature in Celsius. Similarly, the concentration product at equilibrium can be written as \( K_{c} = \frac{{K_{\text{sp}} }}{{f_{D}^{2} }} \) and the equilibrium concentration as \( C* = \sqrt {K_{c} } \). In addition, supersaturation is defined as \( S = \frac{{\left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right]\left[ {{\text{CO}}_{3}^{2 - } } \right]}}{{K_{c} }} \) [28].

Saturation index (SI) indicates CaCO3 precipitation or dissolution tendencies and determines whether the solution is oversaturated, saturated, or undersaturated concerning CaCO3. A positive SI connotes a water oversaturated concerning CaCO3; a negative SI signifies undersaturated water and SI of zero represents water in equilibrium with CaCO3. It is defined as:

where pHs is pH of the water if it were in equilibrium with CaCO3 at the existing calcium ion [Ca2+] and bicarbonate ion [HCO3−] and according to Eq. (21) is calculated as:

where p preceding a variable designates − log of that variable [39]. It should be mentioned that for the derivation of Eq. (22) from Eq. (21), the relation of \( pf_{D} = 4pf_{M} \) is used according to Eqs. (17, 18). It is assumed that only CaCO3 is precipitated during this process and precipitation of CaCO3 results in a reduction of [Ca2+] and other species except H+ and HO− (because the calculations are performed at the specified pH values) in the solution. Therefore, in this work for precipitation amount calculations, at first the calculated [Ca2+] is denoted as \( {\text{Ca}}_{0}^{2 + } \), then if pH—pHs > 0.1 (the precision of pH meter), the new compositions are estimated as:

where infinitesimal conversion of dissolved [Ca2+] to precipitated [CaCO3] is assumed as \( \varepsilon = 10^{ - 4} \). It is noteworthy that during the calculation the condition of \( \left[ {{\text{CO}}_{3}^{2 - } } \right] - \left[ {{\text{Ca}}^{2 + } } \right]\varepsilon \ge 0 \) should be satisfied. The theoretical precipitation amount at each pH in mol/L will be

The calculation of precipitated amount is started at initial high pH and continued for next lower pH values by replacing \( T_{{{\text{Ca}},i}} = T_{{{\text{Ca}},i - 1}} - {\text{Prec}}_{i} ; \) where i is related to descending pH values and the final theoretical precipitation amount is

where V is the volume of suspension and Mw∙CaCO3 is the molecular weight of calcium carbonate. In this work, the related MATLAB program is written to perform the above-mentioned algorithms.

RTD model for the recycled batch system

A schematic setup to establish the model for RTD of the recycled batch system is presented in Fig. 3. Without loss of generality, it is assumed that the volume of pipes is negligible and a vessel with the capacity of V [L] represents the lumped volume of the system and v [L/min] of pure water is recycled to the system. At t = 0, M [mol] of a tracer like KCl is introduced at the entrance of the vessel. The vessel is not perfectly mixed and the solution has a concentration gradient. However, the mean concentration of the tracer in the vessel (a time-dependent value) is denoted by C(t). Since the volume of pipes is negligible, all the output tracer at time t will be instantly added to input flow (not to vessel, the tracer will enter the vessel during \( \tau \)) and the mass balance on the vessel can be expressed as:

By defining \( \tau = \frac{V}{v} \) and \( C_{0} = \frac{M}{V} \) and integration on time for 0 to t that matches to concentration 0 to C, the relation of C(t) can be obtained as:

The relation for RTD can be expressed as:

Results and discussion

It is assumed that at the end of the process the liquid and precipitated phases mainly consist of smaller and bigger particles, respectively. Therefore, because the main goal of this work is the investigation on the nanoparticles, the particle size in the liquid phase was only studied (the particle size in the precipitated phase was not considered) and it can be noted that lower amount of precipitation is more favorable. Table 1 represents the experimental data of different responses at the design conditions for the Saddle type packing and Table 2 shows the same data for the Pall type packing. The last columns of these tables show the range of particle size according to the analysis of FESEM figures. For example, Fig. 4 shows the FESEM figures of two samples. Since except packing type, other experimental conditions of Table 1 are repeated in Table 2, the effect of the packing type on each response (reaction time, precipitation amount or particle size in the liquid phase) can be evaluated through the paired comparison of the data in the corresponding columns. The calculated p value in the case of reaction time is 0.08 and in the case of precipitated amount is 0.87. Therefore, at reasonable level of significance (0.05 as the default of the function t test() in MATLAB), the type of packing cannot be considered to be effective on the reaction time and does not disturb the precipitation amount in this process. As a result, it can be reasonable to consider the column of reaction time in Table 2 as the repeated experiments of the corresponding column in the Table 1 and this conclusion will be consistent in the case of precipitation amount as well. However, according to this statistical model particle size relates (mean particle size is considered) to packing type. The mean size of the particles produced through RPB equipped with Saddle type packing is significantly smaller compared to the setup with Pall type packing. Table 3 shows the p values of different factors on the reaction time as well as precipitation amount regardless of the packing type effect. According to this table, neither factors -in the studied ranges- have significant effect on the considered responses. However, it can be said that omitting the liquid flow effect is more reasonable compared to the other factors. This conclusion is acceptable since the system is semi-batch type and the liquid flow will only have the mixing effect that is compensable with the high rotating speed. In addition, according to a similar statistical analysis, the effect of all the studied factors on particle size can be ignored for saddle as well as pall packing. Nevertheless, the mentioned conclusions are limited to the range of the factors of the experimental setup and the results will be probably changed if a pilot scale with wider range of factors is used. This assumption verified by fitting a second-order response surface to the reaction time of saddle type packing loaded RPB versus two main factors (rotating speed and gas flow rate). Although the adjusted R2 statistic of this model is as low as 0.57, its p value of the test for significance of regression is 0.006 and implies that at least one factor contributes significantly to the model.

The proposed model is used to evaluate total carbonate species according to

As Fig. 5 shows the total concentration of carbonates increases by decreasing of pH in accordance with the injection of CO2 during the reaction, although in the model only the values of TCa and pH are used to estimate other species. According to this figure, the solution of CO2 is higher at some ranges of pH values (pH > 12, 9.5 < pH < 11 and 7 < pH < 7.5). Figure 6 shows equilibrium concentration and supersaturation against pH. The maximum value of C* and S is related to pH 11.4 and theoretically implies that a process with pH control around 11.4 will result in higher product amount. The relation of C* to pH at constant temperature and Ksp is due to relation of fD to pH. The calculations of Figs. 5 and 6 were accomplished for initial 7.155 g of CaO. The pH of maximum supersaturation has a week relation to initial amount of CaO, e.g., for CaO initial amount in the range of 6–9 g, the pH of maximum S varies between 11.33 and 11.42. However, the values of maximum S for CaO initial amount of 6 and 9 g are, respectively \( 9.1 \times 10^{4} \) and \( 1.8 \times 10^{5} \)(the figure does not show here). The induction time that is the time in which supersaturation start to decrease and the crystallization starts on an observable level [28] may be matched to pH of 11.4 according to the theoretical modeling in this work. Although it varies for different experiments of Tables 1 and 2, a typical value is about 20 s according to the data of pH against time (do not presented here). Figure 7 shows the final theoretical precipitation amount of CaCO3 according to Eq. (30) for Test No. 1 of Table 1 and Test No. 26 of Table 2. It can be concluded that after about 100 s the chemical reaction is nearly completed and then the crystallization process without chemical reaction prevails the amount and size of the precipitated CaCO3. In addition, low values of experimental precipitation amount compared to theoretical ones imply that the most of the produced solid particles remain in the liquid phase having nano-size scale.

In this work, KCl is used as a tracer for RTD study and its concentration is estimated using its relation with EC. The relation is obtained by a separate experiment and since the EC of pure water is \( 340\frac{\mu S}{cm} \), it should be subtracted from the measured EC of prepared solutions in the range of CKCl = 0.05–0.15 mol/L. The fitted line obeys the following relation:

where EC* is the measured electrical conductivity in \( \mu S/cm \) minus 340. The RTD experiments were done without gas flow and under 3000 rpm and 3.5 L/min of liquid flow. The initial KCl was added thoroughly in order to run a pulse experiment and to have the following relation:

Figure 8 compares the experimental RTD of the system equipped with pall and saddle packings and theoretical RTD proposed in this work for recycled batch system in addition to RTD of plug and mixed flow. According to this figure, the proposed model is the best one for RPB, unless the first point of the experimental data. The deviation of model at the beginning of the test can be attributed to experimental measurement procedure. According to the derivation of theoretical RTD, the mean concentration of tracer in the vessel should be obtain in order to calculate RTD. However, in this work the EC of output flow from vessel was measured. The associated error will be maximum at the beginning and will tend to zero at the end of the experiment. The analysis of the experimental data shows that although \( \tau = 77s \), for pall type packing the mean residence time of the system is \( \bar{t} \approx 75s \) and for saddle type \( \bar{t} \approx 89s \). The difference between two packing type can be related to the actual free volume and overprediction of the model may be attributed to the experimental errors and numerical integration in the Eq. (36).

Conclusion

According to the experimental data of CaCO3 nanoparticle production via RPB in this work, packing type has the significant effect on particle size but gas flow rate and rotating speed should be investigated in the wider ranges. A simpler and more explicit model for determination of intermediates is proposed for the reaction of CO2 with Ca(OH)2 compared to previous ones. According to this theoretical model, pH 11.4 is proposed to obtain more products. An RTD model is proposed and test for RPB reactors.

References

Kiss, A.A.: Process intensification technologies for Biodiesel Production. Springer, Cham (2014)

Zhao, H., Shao, L., Chen, J.F.: High-gravity process intensification technology and application. Chem. Eng. J. 156, 588–593 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2009.04.053

Visscher, F., van der Schaaf, J., Nijhuis, T.A., Schouten, J.C.: Rotating reactors—a review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 91(10), 1923–1940 (2013)

Fan, H.L., Zhou, S.F., Qi, G.S., Liu, Y.Z.: Continuous preparation of Fe3O4nanoparticles using impinging stream-rotating packed bed reactor and magnetic property thereof. J. Alloy. Compd. 662, 497–504 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.12.025

Lin, C.C., Wu, M.S.: Continuous production of CuO nanoparticles in a rotating packed bed. Ceram. Int. 42, 2133–2139 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.09.123

Sun, B., Zhou, H., Arowo, M., Chen, J., Chen, J., Shao, L.: Preparation of basic magnesium carbonate by simultaneous absorption of NH3 and CO2 into MgCl2 solution in an RPB. Powder Technol. 284, 57–62 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2015.06.043

Lin, C.C., Lin, Y.C.: Preparation of ZnO nanoparticles using a rotating packed bed. Ceram. Int. 42, 17295–17302 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.08.025

Chen, J., Shao, L., Zhang, C., Chen, J., Chu, G.: Preparation of TiO2 nanoparticles by a rotating packed bed reactor. J. Mater. Sci. 22, 437–439 (2003)

Hu, T.T., Wang, J.X., Shen, Z.G., Chen, J.F.: Engineering of drug nanoparticles by HGCP for pharmaceutical applications. Particuology 6, 239–251 (2008)

Tai, C.Y., Wang, Y.H., Kuo, Y.W., Chang, M.H., Liu, H.S.: Synthesis of silver particles below 10 nm using spinning disk reactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 64, 3112–3119 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2009.03.041

Chen, J.F., Wang, Y.H., Guo, F., Wang, X.M., Zheng, C.: Synthesis of nanoparticles with novel technology: high-gravity reactive precipitation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 39, 948–954 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1021/ie990549a

Chen, J-F., Shao, L., Guo, F., Wang, X-M.: Synthesis of nano-fibers of aluminum hydroxide in novel rotating packed bed reactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 58(3–6), 569–575 (2003)

Sun, B.-C., Wang, X.-M., Chen, J.-M., Chu, G.-W., Chen, J.-F., Shao, L.: Synthesis of nano-CaCO3 by simultaneous absorption of CO2 and NH3 into CaCl2 solution in a rotating packed bed. Chem. Eng. J. 168, 731–736 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.01.068

Chen, J., Shao, L.: Mass production of nanoparticles by high gravity reactive precipitation technology with low cost. China Particuol. 1, 64–69 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1672-2515(07)60110-9

Passaretti, J.D., Young, T.D., Herman, M.J., Duane, K.S., Bruce, D.: Application of high-opacity precipitated calcium carbonate. Tappi J. 76, 135–140 (1993)

Dong, W., Cheng, H., Yao, Y., Zhou, Y., Tong, G., Yan, D., Lai, Y., Li, W.: Bioinspired synthesis of calcium carbonate hollow spheres with a nacre-type laminated microstructure. Langmuir 27, 366–370 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1021/la1034799

Declet, A., Reyes, E., Suarez, O.M.: Calcium carbonat precipitaion: a review of the carbonate crystallization process and applications in ioinspired composite. Int. J. Adv. Mater. Sci. 44, 87–107 (2016)

Mitsuishi, K., Kodama, S., Kawasaki, H.: Mechanical properties of polyethylene/ethylene vinyl acetate filled with calcium carbonate. Polym. Compos. 9, 112–118 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.750090203

Kamba, A.S., Tengku, T.A.: Synthesis and characterisation of calcium carbonate aragonite nanocrystals from cockle shell powder (Anadara granosa). J. Nanomater. 2013, 1–9 (2013)

Ghadam, G.J.: Characterization of CaCO3 nanoparticles synthesized by reverse microemulsion technique in different concentrations of surfactants. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 32, 27–35 (2013)

Ren, M., Dong, C., An, C.: Large-scale growth of tubular aragonite whiskers through a MgCl2-assisted hydrothermal process. Mater. (Basel). 4, 1375–1383 (2011). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma4081375

Chen, J., Wang, Y.: Synthesis and application of nanoparticles by multiphase reactive precipitation in a high-gravity reactor: I: experimental. In: Processing by Centrifugation. Springer, Boston, MA, pp. 19–28 (2001)

Xiang, Y., Wen, L., Chu, G., Shao, L., Xiao, G., Chen, J.: Modeling of the precipitation process in a rotating packed bed and its experimental validation. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 18, 249–257 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1004-9541(08)60350-X

Sung, W.Der, Chen, Y.S.: Characteristics of a rotating packed bed equipped with blade packings and baffles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 93, 52–58 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2012.03.033

Guo, K., Guo, F., Feng, Y., Chen, J., Zheng, C., Gardner, N.C.: Synchronous visual and RTD study on liquid flow in rotating packed-bed contractor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 55, 1699–1706 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2509(99)00369-3

Feng, X., Patterson, D.A., Balaban, M., Emanuelsson, E.A.C.: Characterization of liquid flow in the spinning cloth disc reactor:residence time distribution, visual study and modeling. Chem. Eng. J. 235, 356–367 (2014)

Yang, H.J., Chu, G.W., Xiang, Y., Chen, J.F.: Characterization of micromixing efficiency in rotating packed beds by chemical methods. Chem. Eng. J. 121, 147–152 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2006.04.010

Mersmann, A.: Crystallization technology handbook. Dry. Technol. 13, 1037–1038 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1080/07373939508917003

Wiechers, H., Sturrock, P., Marais, G.: Calcium carbonate crystallization kinetics. Water Res. 9, 31–36 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1021/i100005a006

Coto, B., Martos, C., Peña, J.L., Rodríguez, R., Pastor, G.: Effects in the solubility of CaCO3: experimental study and model description. Fluid Phase Equilib. 324, 1–7 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fluid.2012.03.020

Al Nasser, W.N., Al Salhi, F.H.: Kinetics determination of calcium carbonate precipitation behavior by inline techniques. Powder Technol. 270, 548–560 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2014.05.025

de Moel, P.J., van der Helm, A.W.C., van Rijn, M., van Dijk, J.C., van der Meer, W.G.J.: Assessment of calculation methods for calcium carbonate saturation in drinking water for DIN 38404–10 compliance. Drink. Water Eng. Sci. 6, 115–124 (2013). https://doi.org/10.5194/dwes-6-115-2013

Wolthers, M., Nehrke, G., Gustafsson, J.P., Van Cappellen, P.: Calcite growth kinetics: modeling the effect of solution stoichiometry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 77, 121–134 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.11.003

Ropp, R. (ed.): Chapter 10. Group 6 (Cr, Mo and W) Alkaline earth compounds. In: Encyclopedia of the Alkaline Earth Compounds, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 795–868 (2013)

Tai, C.Y., Chen, P.: C: nucleation, agglomeration and crystal morphology of calcium carbonate. AIChE J. 41, 68–77 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690410108

Thriveni, T., Um, N., Nam, S.Y., Ahn, Y.J., Han, C., Ahn, J.W.: Factors affecting the crystal growth of scalenohedral calcite by a carbonation process. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 51, 107–114 (2014). https://doi.org/10.4191/kcers.2014.51.2.107

Kawano, J., Shimobayashi, N., Miyake, A., Kitamura, M.: Precipitation diagram of calcium carbonate polymorphs: Its construction and significance. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 21(42), 425102 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/21/42/425102

Plummer, L.N., Busenberg, E.: The solubilities of calcite, aragonite and vaterite in CO2–H2O solutions between 0 and 90°C, and an evaluation of the aqueous model for the system CaCO3–CO2–H2O. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 46(6), 1011–1040 (1982)

APHA: Standard Methods for examination of water and wastewater (standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater). Stand. Methods. 5–16 (1998)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contribution statement

ME conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, developing theoretical model, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. MS participated in the design and coordination of the study and performed the measurement. SB participated in the design and coordination of the study and performed the measurement.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Emami-Meibodi, M., Soleimani, M. & Bani-Najarian, S. Toward enhancement of rotating packed bed (RPB) reactor for CaCO3 nanoparticle synthesis. Int Nano Lett 8, 189–199 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40089-018-0244-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40089-018-0244-4