Abstract

Homebound older adults are more likely than their ambulatory peers to suffer from depression. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of antidepressant medications alone in such cases is limited. Greater benefits might be realized if patients received both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy to enhance their skills to cope with their multiple chronic medical conditions, isolation, and mobility impairment; however, referrals to specialty mental health services seldom succeed due to inaccessibility, shortage of geriatric mental health providers, and cost. Since a large proportion of homebound older adults receive case management and other services from aging services network agencies, the integration of mental health services into these agencies is likely to be cost-efficient and effective. This review summarizes recent advances in home-based assessment and psychosocial treatment of depression in homebound recipients of aging services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite projections that overall disability rates in later life will continue to decline [1, 2], the rapid growth of the older-adult population is likely to increase the number of homebound older adults who require in-home support services for their physical, functional, and mental health needs. According to the 2011 U.S. Census data, of 40 million noninstitutionalized adults age 65 years and older, 9.2 million (23.5 %) had ambulatory disability and 6.2 million (15.8 %) had independent living disability [3]. In calendar year 2010, the Medicare home health care program served just fewer than 3 million older adults and paid out $16.8 billion ($5,669 per person) for their home health services, and the Medicare skilled nursing facility services served 2.3 million older adults and paid out $25.1 billion ($10,866 per admission) [4]. Home-based care tends to be less costly than institutional care. However, given many older adults’ strong preference for aging in place [5], the demand for home-based care for the chronic physical and mental health problems of the growing numbers of homebound older adults will continue to increase, requiring innovative and cost-effective solutions for this significant public health need.

Epidemiologic and other community-based studies over the past two decades consistently found that older adults who were homebound due to chronic illness and disability suffered from major depressive disorder (MDD) or clinically significant depressive symptoms at a rate two to three times higher than that of their ambulatory peers [6–10]. In one study, 13 % of homebound older-adult respondents reported suicidal ideation [10], and in other studies, almost half of homebound older adults with MDD reported symptoms of suicidal ideation, including 6 % who were actively suicidal [11, 12]. Both persistent and new-onset disability increase the risk for depression [13], and among low-income homebound older adults, social isolation and financial worries/hardship were also found to be depression risk factors [7, 14]. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms are more common than major or minor depression among homebound and other community-dwelling older adults, but they, like MDD, are associated with significantly increased functional and psychosocial impairments and may represent a common and integral part of the long-term course of MDD [15–18]. Regardless of its severity, untreated late-life depression has serious negative health effects, which in turn results in higher rates of healthcare service utilization, premature institutionalization, and mortality [19, 20].

Antidepressant medication use among older adults has significantly increased in recent years [21]. A significant proportion of depressed homebound older adults take antidepressant medications (e.g., from 11.5 % in 2000 to 39.5 % in 2007 regardless of diagnosis) [22], mostly prescribed by their primary care physicians; however, many have limited response to medication alone and remain symptomatic, due in part to subtherapeutic dosing, inadequate monitoring by the clinicians, and poor patient adherence [23–25]. Thus, despite rapid increase in the proportion of homebound older adults being prescribed antidepressants, depression remains insufficiently treated and persistent in the majority of these seniors.

Most depressed homebound older adults prefer psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy [26, 27], perhaps because only the former can teach skills to cope with their multiple chronic medical conditions, disability, social isolation, and limited financial resources [28, 29]. However, referring homebound older adults to specialty mental health services for psychotherapy seldom succeeds due to inaccessibility, shortage of geriatric mental health providers, and cost [30]. Providing in-person psychotherapy is especially expensive for homebound patients, given the costs associated with travel (of clinicians to homes or disabled patients to offices). Despite the high rate of depression among homebound older adults, their mental health needs are largely unmet.

Recent efforts to increase homebound older adults’ access to psychosocial interventions focus on integrating mental health provision into existing home-based care offered by aging services and home healthcare settings and/or on taking advantage of technological advances [31••, 32•]. In this paper, we review recent advances in assessment and psychosocial treatment of depression in homebound older adults who are served by the aging services network. For a summary of new developments in home healthcare service settings, please refer to an earlier work by the last author [33]. Following the definition of “homebound” older adults by Medicare [34], the term homebound adults in this study refers to older individuals who, due to medical conditions and/or mobility-affecting impairments, cannot freely leave their home and who require help in doing so.

Aging Services Settings

The 1965 enactment of the Older Americans Act (OAA) established federal and state agencies to address the social service needs of the aging population. The goal of the OAA was to help older adults (age 60 years and older) maintain maximum independence in their homes and communities and to promote a continuum of care for vulnerable older adults. In successive amendments, the Act created area agencies on aging (AAAs) and a host of service programs. The “aging services network” refers to the agencies, programs, and activities that are sponsored by the OAA [35]. Major services provided by the aging services network include access to services (information and referral, benefits counseling, case management, transportation); nutrition (nutrition counseling and education, congregate meals and home-delivered meals, or “Meals on Wheels”); home- and community-based long-term care (short-term homecare/housekeeping/personal assistance care, adult day care, family caregiver support); disease prevention and health promotion (immunization, fall prevention, medication management); vulnerable-elder rights program (long-term care ombudsman, elder abuse and neglect prevention, and legal assistance); and services to Native Alaskans, Native Hawaiians, and Native Americans. Current OAA organizations include 56 state units on aging, 629 area agencies on aging, 244 tribal and Native American organizations, and 20,000 local service organizations [36].

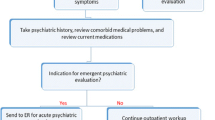

Since a large proportion of homebound older adults are served by aging services network agencies for case management and other social and health service needs, the integration of mental health services into aging services is likely to be a cost-efficient and effective way to serve the mental health needs of these vulnerable older adults. As a reflection of the increasing awareness of the importance of late-life mental health issues, the OAA Amendments of 2006 stipulate funding availability for mental health screening, diagnosis, and treatment as important parts of community-based agencies and strongly encourage OAA-funded agencies to directly provide or purchase mental health services for their clients [37]. Despite this potential funding availability, most aging services network agencies currently do not provide depression care for their clients because they lack staff trained in depression intervention. Most agencies also face barriers to referring their clients out for treatment because of the shortage of mental health professionals who are able and willing to provide in-home treatment. In recent years, however, some pioneering work has been done to integrate depression screening as part of case management assessments in aging services agencies and to provide home-based depression treatment using telehealth delivery, as summarized below.

Tools for Depression Screening of Homebound Older Adults Served by Aging Services

Given the high caseloads of aging service agencies, there is the need to identify the most efficient depression screening tool. The Patient Health Questionnare-9 [38, 39] has been widely used as an effective, efficient depression screening tool for both symptom severity and probable diagnosis in many randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of depression in primary care settings. The PHQ-9 was also successfully used as an assessment tool to identify depression in homebound older adults served by homecare agencies or home-delivered meals programs [7, 9, 10]. In 2010, Medicare required home healthcare agencies to use a revised version of the Outcome Assessment and Information Set (OASIS) that includes a two-item version of the PHQ or PHQ-2 [40]. Medicare also integrated the full PHQ-9 into the revised assessments (MDS 3.0) for nursing home residents in 2011 [41]. Many aging services agencies (e.g., in New York City) have begun augmenting their routine assessment with the PHQ-9 or the PHQ-2 [42].

A community-academic research partnership in Monroe County, N.Y., evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the PHQ-2 (score range 0–6), the PHQ-9 (score range 0–27), and the two-step PHQ-2/9 (calculation of PHQ-9 score among only those subjects who screened positive on the PHQ-2 at a cut point of ≥ 2) in a sample of 378 aging services clients [43]. The standard criterion was the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR. When they used a cut score of 3, the sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-2 were 0.80 and 0.78, respectively. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for the PHQ-2 was 0.87. When they used a cut score of 10, the sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-9 were 0.82 and 0.87, respectively, and the AUC was 0.91. The sensitivity and specificity of the two-stage PHQ-2/9 were 0.81 and 0.89, respectively. The findings show that in aging services settings where a false-positive test has high cost implications, the greater specificity of the PHQ-9 makes it more advantageous than the PHQ-2. The PHQ-2/9 also appears to be efficient for an agency to administer. The same community-academic research partnership also evaluated the performance of the PHQ-2 and the PHQ-9 for aging services clients with cognitive impairment (≥ 2 errors on the Six-Item Screen) [44•]. The PHQ-2, using a cutoff of 3, had a sensitivity of 0.78 and a specificity of 0.71, and the PHQ-9, using a cutoff of 10, had a sensitivity of 0.89, a specificity of 0.71, and an AUC of 0.85, indicating that the cognitive status needs to be considered when using the PHQ as a depression screener.

Another screening tool for depression (and anxiety) that has shown promise in its use with homebound older adults is the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) [45]. Investigators evaluated its factor structure, internal consistency, and concurrent validity in a sample of 142 homebound older adults, age 60 years and older, receiving in-home aging services in Florida. With the DSM-IV as the standard criterion, the BSI-18 depression subscale had an AUC of 0.89, a sensitivity of 0.88, and a specificity of 0.62 when using the cut score of T = 50. The AUC for the three-item depression scale was 0.88, its sensitivity was 0.88, and its specificity was 0.74 when using a cut score ≥ 3. The ROC analysis of the BSI-18 anxiety subscale yielded an AUC of 0.80 and a sensitivity of 0.88 and a specificity of 0.61 when using a T-score of 49. However, because only homebound older adults who had cognitive ability to consent and had no dementia diagnosis were selected to participate, it is not known if the BSI-18 will be a valid screening tool for those with cognitive impairment.

Treatment of Depression in Homebound Older Adults: Evidence-Based Psychosocial Interventions

In its 2011 publication on treatment of depression in older adults, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) lists the following psychotherapies as being evidence based: cognitive behavioral therapy; behavioral therapy; problem-solving therapy; interpersonal therapy; reminiscence therapy; and cognitive bibliotherapy [46]. Of these, problem-solving therapy (PST) has a growing evidence base for use with both ambulatory and homebound older adults. Our group recently completed an RCT of telehealth-delivered PST (tele-PST) for homebound older adults and found it to be as effective as in-person PST. Other treatments that have been found efficacious for helping homebound older adults are PATH (problem-adaptation therapy, PEARLS (Program to Encourage Active, Rewarding Lives for Seniors), and Healthy IDEAS (Identifying Depression, Empowering Activities for Seniors). Of these, the latter two (PEARLS and Healthy IDEAS) have been selected (along with the IMPACT program), as evidence-based programs for treating late-life depression by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors. They are multi-component, home-based interventions that collaborate with community-based agencies to provide depression screening, outreach, and treatments such as problem-solving skills training and behavioral activation in conjunction with geriatric case management and other aging services [47••]. This section also describes these and other recent developments in depression treatment for homebound older adults.

Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) and Telehealth-Delivered PST (Tele-PST)

Problem-solving therapy is a treatment based on the social problem-solving theory of depression, which posits that the relationship between stressors and depression is influenced by the availability of problem-solving skills [48, 49]. People with deficits in problem-solving skills become vulnerable to depression because such deficits lead to ineffective coping attempts under high stress levels. Problem-solving therapy facilitates optimistic orientation toward problem-solving and follows seven steps, including appraisal and evaluation of specific “here-and-now” problems, identification of the best possible solutions, and the practical implementation of those solutions, as well as addressing anhedonia and psychomotor retardation through behavioral activation and increased exposure to pleasant events [50, 51]. The efficacy of PST-PC (i.e., delivery of PST in fast-paced primary care settings), alone or in combination with antidepressant medications, has been supported in multiple RCTs, including the IMPACT study, a multisite RCT of late-life depression treatment in primary care settings [52, 53•, 54, 55]. An RCT that tested efficacy of in-home PST (six weekly sessions) for older-adult patients of a home healthcare agency in New York found a significant reduction in their depressive symptoms over a 6-month period [56].

Given that in-home, in-person PST is unlikely to be sustainable in aging service agencies due to its high cost, our group tested the efficacy of tele-PST, or PST sessions delivered via Skype video call to homebound older adults who were not cognitively impaired. Videoconferenced delivery has several advantages over telephone delivery because its visual contact, through which the therapist can see the client’s facial expression and body language, allows most of the benefits of in-person sessions and more effective therapeutic engagement than telephone sessions. Participants (121 low-income homebound older adults), who had moderately severe and severe depressive symptoms (24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAMD] ≥ 15) at baseline, were randomly assigned to six weekly sessions of tele-PST, in-person PST, and telephone care call (attention control). A laptop with Skype function and wireless card was loaned to each tele-PST participant. The follow-up assessments found (1) that tele-PST and in-person PST participants had significantly lower depression scores than telephone care call participants, and (2) that tele-PST and in-person PST participants were not different from each other. Standardized mean difference effect sizes for HAMD score changes were ES sm = 0.77 for tele-PST and ES sm = 0.70 for in-person PST at 12-week follow-up and ES sm = 0.66 for tele-PST and ES sm = 0.45 for in-person PST at 24-week follow-up [57•]. Although some participants were initially hesitant to engage in therapy via videoconferencing, almost all tele-PST participants ended up accepting and liking the tele-delivery method. Simple cost analysis showed that tele-delivery cost was lower than in-person delivery cost, including the therapist’s travel time and mileage. The acceptability, preliminary efficacy, and cost-saving potential of tele-PST point to its promise as a depression treatment modality for homebound older adults that can be integrated into aging service settings.

Positive outcomes of previous studies of PST with older adults who had mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [53•, 58] present possibilities for using tele-PST with homebound older adults who have MCI, by using longer sessions and an approach that is more therapist-directed and less client-driven than the protocol for the RCT described above. With the rapid advance of tele-technology, rapid uptake of computer and Internet use among older adults, and potential cost-effectiveness, tele-PST or other telehealth-delivered psychosocial interventions have strong potential for future implementation and long-term sustainability in aging services settings that serve depressed homebound older adults.

Problem-Adaptation Therapy (PATH)

For cognitively impaired homebound older adults, Kiosses and colleagues [59•] developed PATH, a 12-week home-delivered intervention designed to address depression and disability in this group of older adults. The PATH model is grounded in Lawton’s ecological model of adaptive functioning [60], which emphasizes the person’s ecosystem, including caregivers and home environment, and uses environmental adaptations to help the person gain a sense of competence within his/her home environment despite various functional and behavioral limitations. In a RCT with 30 patients assigned to either PATH or in-home supportive therapy, the developers found that the PATH group demonstrated a greater decrease in depressive symptoms and disability over the 12-week period than did the in-home supportive therapy group.

Program to Encourage Active, Rewarding Lives for Seniors (PEARLS)

The PEARLS program, a community-integrated, home-based depression treatment, was initially tested in an RCT with 138 older adults, age 60 years and older, receiving services from senior service agencies or living in senior public housing and meeting the DSM-IV minor depression or dysthymia diagnostic criteria [61]. The intervention, consisting of eight PST sessions modified to provide greater emphasis on social and physical activation, was compared to usual care. At 12 months, compared with the usual care group, patients receiving the PEARLS intervention were more likely to have at least a 50 % reduction in depressive symptoms (43 % vs. 15 %; odds ratio [OR], 5.21; 95 % confidence interval [CI], 2.01-13.49), to achieve complete remission from depression (36 % vs. 12 %; OR, 4.96; 95 % CI, 1.79-13.72), and to have greater health-related quality-of-life improvements in functional well-being (p = .001) and emotional well-being (p = .048). The PEARLS program has since been developed and implemented as a depression care management program provided by public and nonprofit aging service agencies and other existing community-based health and social service providers in several states. According to the PEARLS website (www.pearlsprogram.org), the program uses a team-based approach, involving PEARLS counselors, supervising psychiatrists and medical providers, and in its six to eight in-home sessions, it focuses on teaching clients brief behavioral techniques and skills to empower those who suffer from chronic medical conditions (including epilepsy [62]) and depression to take action. A recent paper [63•] on perspectives from the PEARLS staff and former clients reported that the community-based agency staff recognized PEARLS as a comprehensive program to help them meet clients’ mental health needs. On the other hand, these agency staff also pointed out the barriers to program implementation with respect to rigid eligibility criteria (e.g., not including MDD and other comorbid mental disorders such as schizophrenia) and time needed for two depression screens (11-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale followed by the PHQ-9), especially with the high caseloads of case managers who are expected to refer their clients to PEARLS. The PEARLS program is trying to alleviate these barriers in order to reach a greater number of depressed older adults.

Healthy IDEAS

Healthy IDEAS (http://careforelders.org/default.aspx?menugroup=healthyideas) is a home-based program that integrates depression awareness and management into existing case management services provided to older adults with chronic medical conditions and functional impairments. Its components are routine screening and assessment of depressive symptom severity as part of case management; educating older adults and caregivers about depression and self-care; linking older adults to primary care and mental health providers and to active assistance in obtaining further treatment; and coaching and supporting older adults to manage their depression through a behavioral activation approach that encourages involvement in meaningful activities. Through its linking service, which includes appropriate referrals, better communication, and effective partnerships, the program seeks to improve the linkage between community aging service providers (e.g., area agencies on aging) and health care professionals. Since the program started in Houston, Tex., it has been replicated by service providers in several states. Its outcome study found that participants showed reductions in depression severity and self-reported pain, increased knowledge of how to get help for depression, increased activity levels, and knowledge of ways to manage depressive symptoms [64].

Other Home-Based Depression Intervention Programs

Beat the Blues for Older African Americans (BTB)

A randomized trial is now underway for the BTB program, which is designed to reduce depressive symptoms and improve quality of life in 208 African Americans age 55 years and older [65]. . Care managers at a senior center screen for depressive symptoms using the PHQ-9, either by telephone or in person, on two separate occasions over a 2-week period, after which eligible older adults are referred to local mental health resources. The intervention group also receives referral to BTB. A licensed senior center social worker trained in BTB meets with each BTB participant in the participant’s home for up to 10 sessions over 4 months for assessments of care needs, referrals/linkages, depression education, learning of stress reduction techniques, and use of behavioral activation to identify goals and steps to achieve the goals. Although the BTB outcomes are not yet available, the BTB is very promising as a home-based depression intervention, especially because it utilizes a neighborhood senior center staff to screen depression and provide interventions. The research team reported the total costs per participant are $585 for 4 months or $146 per month, indicating that it may also be a relatively low-cost program.

Telemonitor-Based Depression Care Management

Sheeran and colleagues [66] tested the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary clinical outcomes of telemonitor-based depression care management for homebound older adults served by homecare service agencies in New York, Vermont, and Miami. The 48 participating older adults, both English- and Spanish-speaking, were already receiving telemonitoring as part of their home healthcare services, and the research team leveraged the existing telemonitor platform to incorporate evidence-based depression care management by programming questions and educational information on depressive symptoms (PHQ-2 administered via telemonitor), antidepressant adherence, and side effects for up to 3 weeks. Questions regarding antidepressant treatment were developed to use the same format that home telemonitors typically use for other disease management. Telehealth homecare nurses were trained as depression care managers, and the training was built on a depression care management protocol developed as part of an academic-practice partnership for in-person home healthcare [67]. The results of this pilot study supported the feasibility and positive clinical outcomes (depression severity) of using homecare’s existing telemonitoring technology to deliver depression care management to homebound older adults. Although these findings require rigorous testing in a RCT, they suggest that the delivery model is promising.

Conclusions

Due to their chronic medical conditions and the social isolation caused by mobility impairment, homebound older adults are more vulnerable to depression than their ambulatory peers. However, their homebound state is a barrier to detection and treatment of their depression. Regardless of symptom severity, untreated depression in late life has been found to lead to further impairments in physical and psychosocial function and higher healthcare costs among older adults. The high prevalence rate of depression in homebound older adults is a significant public health problem. This summary of recent trends focused on two approaches to this problem: (1) the growing effort to integrate depression screening into routine case management assessments of aging services agencies that already serve these homebound older adults and (2) effective and efficient psychosocial interventions that also can be provided by the aging services agency staff, or by licensed mental health professionals in partnership with aging service agencies. The integration of depression screening into routine aging service assessment has the potential to maximize reach to this group of older adults suffering from the costly burden of depression along with other medical problems. The evidence base of short-term psychosocial interventions for late-life depression is expanding, and the AoA and SAMHSA jointly call for the integration of these evidence-based interventions into aging services and for the utilization of technology to improve effectiveness and efficiency. Our review identified a few innovative and promising approaches that have the potential to be integrated into aging services.

In sum, there is a solid accumulated knowledge base regarding the potential effectiveness of the integration of mental health services into aging services settings. However, a remaining challenge is to find effective and efficient strategies not just to disseminate but also to support the uptake, implementation and sustainability of these interventions in routine care of aging service agencies [68, 69]. At the system level, major challenges include the overall geriatric mental health workforce shortage [70], insurance limitations (e.g., Medicare’s restricted payment rules for telemental health delivery) and other uncertainties regarding funding streams, and staff shortage and high caseload in most aging service settings. Along with developing the geriatric mental health workforce, implementation of evidence-based interventions requires dealing with issues related to licensing of interventionists, fidelity monitoring, and financial and other sustainability [71]. Future research needs to identify the most cost-effective, efficient, and sustainable ways to meet the treatment need of depressed homebound older adults.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

He W, Sengupta M, Veikoff VA, DeBarros KA. 65+ in the United States: 2005. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P23-209. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005.

Jacobs JM, Maaravi Y, Cohen A, et al. Changing profile of health and function from age 70 to 85 years. Gerontol. 2012;58:312–21.

United States Census Bureau. Table 35. Persons 65 Years and Over—Living Arrangements and Disability Status, 2009. Statistical Table Based on data from the 2009 American Community Survey. Available at http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0035.pdf. Accessed October 2012.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Supplemental Statistics, 2011. Tables 7.2 Persons Served, Visits, Total Charges, Visit Charges, and Program Payments for Medicare Home Health Agency Services: Calendar Year 2010; and Table 6.2 Covered Admissions, Covered Days of care, Covered Charges, and Program Payments for Skilled Nursing Facilities Used by Medicare Beneficiaries: Calendar Year 2010. Available at http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/2011.html. Accessed October 2012.

Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, et al. The meaning of "aging in place" to older people. Gerontologist. 2012;52:357–66.

Bruce ML, McVay J, Raue PJ, et al. Major depression in elderly home health care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1367–74.

Choi NG, Teeters M, Perez L, et al. Severity and correlates of depressive symptoms among recipients of Meals in Wheels: Age, gender, and racial/ethnic difference. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:145–54.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2358–62.

Ell K, Unützer J, Aranda M, et al. Routine PHQ-9 depression screening in home health care: Depression prevalence, clinical and treatment characteristics, and screening implementation. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2005;24:1–19.

Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Carpenter M, et al. Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among older adults receiving home-delivered meals. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:1306–11.

Raue PJ, Meyers BS, Rowe JL, et al. Suicidal ideation among elderly homecare patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:32–7.

Rowe JL, Conwell Y, Schulberg HC, Bruce ML. Social support and suicidal ideation in older adults utilizing home healthcare services. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:758–66.

Weinberger ML, Raue PJ, Meyers BS, Bruce ML. Predictors of new onset depression in medically ill, disabled older adults at 1 year follow-up. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:802–9.

Johnson CM, Sharkey JR, Dean WR. Indicators of material hardship and depressive symptoms among homebound older adults living in North Carolina. J Nutrition Grontol Geriatr. 2011;30:154–68.

Lyness JM, Kim J, Tang W, et al. The clinical significance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:214–23.

Lyness JM. Naturalistic outcomes of minor and subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:773–81.

Cui X, Lyness JM, Tang W, et al. Outcomes and predictors of late-life depression trajectories in older primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:406–15.

Lyness JM, Chappman BP, McGriff J, et al. One-year outcomes of minor and subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:60–8.

Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, et al. Increased medical care costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:897–903.

Unutzer J, Schoenbaum M, Katon WJ, et al. Healthcare costs associated with depression in medically ill fee-for-service Medicare participants. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:506–10.

Akincigil A, Olfson M, Walkup JT, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in older community-dwelling adults: 1992–2005. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1042–51.

Weissman J, Meyers BS, Ghosh S, Bruce ML. Demographic, Clinical and Functional Factors Associated with Antidepressant Use in the Home healthcare Elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:1042–5.

Choi NG, Bruce ML, Marinucci ML, et al. Self-reported antidepressant use among depressed, low-income homebound older adults: Class, type, correlates, and perceived effectiveness. Brain Behav. 2012;2:176–86.

Kales HC, Nease DE Jr, Sirey JA, et al. racial differences in adherence to antidepressant treatment in late life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012, Oct 10. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 23060311.

Maust DT, Oslin DW, Thase ME. Going Beyond Antidepressant Monotherapy for Incomplete Response in Nonpsychotic Late-Life Depression: A Critical Review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012, Oct 5. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 23044641.

Gum AM, Areán PA, Hunkeler E, et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist. 2006;46:14–22.

Choi N, Morrow-Howell N. Older adults’ attitudes toward depression treatment modalities: Within-group differences and comparison with their caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:422–33.

Areán PA, Reynolds CF. The impact of psychosocial factors on late-life depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:277–82.

Cohen A, Houck PR, Szanto K, et al. Social inequalities in response to antidepressant treatment in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:50–6.

Choi NG, Lee A, Goldstein M. Meals on Wheels: Exploring Potential for and Barriers to Integrating Depression Intervention for Homebound Older Adults. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2011;30:214–30.

•• Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Older Americans Behavioral Health Technical Assistance Center. Older Americans behavioral health issue brief: Series overview. 2012. Available at http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/AoA_Programs/HPW/Behavioral/docs/OA_Issue_BriefSeriesOverview.pdf. Accessed October 2012. This overview emphasizes the significance of the integration of aging services and mental health services and utilization of technology in doing so.

• Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Older Americans Behavioral Health Technical Assistance Center. Older Americans behavioral health issue brief 1. 2012. Available at http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/AoA_Programs/HPW/Behavioral/docs/OA_IssueBrief1_ServicesNetwork_508_12JUN07_dr.pdf. Accessed October 2012. This issue brief is one of the series produced by the SAMHSA about older adults’ mental health issues.

Bazelais KN, Pickett YR, Bruce ML. Late-life mood disorders and home-based services and interventions. In Late-life mood disorders. Edited by Lavrezsky H, Sajatovi M, Reynolds C. New York: Oxford University Press. In press.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Definition of Homebound. Available at http://www.medicare.gov/homehealthcompare/Resources/Glossary.aspx?toolAudiance=HHC&Language=English&TermID=0026. Accessed October 2012.

O’Shaughnessy CV. The Aging Services Network: Accomplishments and Challenges in Serving a Growing Elderly Population. National Health Policy Forum background paper. 2008. April 11. Available at http://www.nhpf.org/library/background-papers/BP_AgingServicesNetwork_04-11-08.pdf. Accessed October 2012.

Administration on Aging. Facts. 2012. Available at http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/Press_Room/Products_Materials/fact/pdf/AoA_Factsheet.pdf. Accessed October 2012.

Administration on Aging. Outline of 2006 Amendments to the Older Americans Act. 2011. Available at http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/aoa_programs/oaa/oaa.aspx. Accessed October 2012.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiat Ann. 2002;32:509–15.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Inter Med. 2001;16:606–813.

Sheeran T, Reilly CF, Raue PJ, et al. The PHQ-2 on OASIS-C: A new resource for identifying geriatric depression among home health patients. Home Healthc Nurse. 2010;28:92–102.

Saliba D, DiFilippo S, Edelen MO, et al. Testing the PHQ-9 interview and observational versions (PHQ-9 OV) for MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:618–25.

Berman J, Furst LM. Depressed older adults: Education and screening. New York: Springer; 2010.

Richardson TM, He H, Podgorski C, et al. Screening depression aging service clients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:1116–23.

• Boyle LL, Richardson TM, He H, et al. How do the PHQ-2, the PHQ-9 perform in aging services clients with cognitive impairment? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:952–60. This paper reports the first systematic evaluation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 among older adults served by aging-service agencies.

Petkus AJ, Gum AM, Small B, et al. Evaluation of the factor structure and psychometric properties of the brief Symptom Inventory-18 with homebound older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:578–87.

U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services, Center for Mental Health Services Administration. The Treatment of Depression in Older Adults: Selecting Evidence-Based Practices for Treatment of Depression in Older Adults. HHS PubNoSMA-11-4631. 2011. Rockville, MD.

•• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Association of Chronic Disease Directors. The State of Mental Health and Aging in America Issue Brief 2: Addressing Depression in Older Adults: Selected Evidence-Based Programs. Atlanta, GA: National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, 2009. This issue brief provides a summary of selected evidence-based psychotherapies for late-life depression.

D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention. New York: Springer; 1986.

Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Perri MG. Problem-solving therapy for depression: Theory, research, and clinical guidelines. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989.

D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Problem-Solving Therapy: A positive approach to clinical intervention. New York: Springer; 2007.

Mynors-Wallis L. Problem-solving treatment for anxiety and depression: A practical guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Areán PA, Hegel MT, Vannoy S, et al. Effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for older, primary care patients with depression: Results from the IMPACT study. Gerontologist. 2008;48:311–24.

• Areán PA, Raue PJ, Mackin S, et al. Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction. Am J Psychiat. 2010;167:1391–8. The paper reports the findings of a large randomized clinical trial that examined the effectiveness of in-person problem-solving therapy vis-à-vis supportive therapy for older adults with mild cognitive impairments.

Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kiosses DN, et al. Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction: Effect on disability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:33–41.

Cuijpers PA, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Problem-solving therapies for depression: A meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:9–15.

Gellis Z, McGinty J, Horowitz A, et al. Problem-solving therapy for late-life depression in home care: A randomized field trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:968–78.

• Choi NG, Hegel MT, Marti CM, et al. Telehealth Problem-Solving Therapy for Depressed Low-Income Homebound Older Adults: Acceptance and Preliminary Efficacy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012, Aug 31. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 22948295. This paper reports the feasibility and efficacy of home-based telehealth-delivered problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults.

Alexopoulos GS, Raue P, Areán PA. Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:46–51.

• Kiosses DN, Arean PA, Teri L, Alexopoulos GS. Home-delivered problem adaption therapy (PATH) for depressed, cognitively impaired, disabled elders: A preliminary study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:988–98. This paper reports the feasibility and efficacy of findings of a small randomized controlled trial of the PATH program for homebound, cognitively impaired older adults and their caregivers.

Lawton MP, Windely PG, Byerts TO. Aging and the environment: Theoretical approaches. New York: Springer; 1982.

Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, et al. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults. JAMA. 2004;29:1569–77.

Chaytor N, Ciechanowski P, Miller JW, et al. Long-term outcomes of the PEARLS randomized trial for the treatment of depression in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;20:545–9.

• Steinman L, Cristofalo M, Snowden M. Implementation of an evidenced-based depression care management program (PEARLS): Perspectives from staff and former clients. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:110250. This paper reports barriers to PEARLS delivery and recommended solutions by aging service agency staff.

Quijano LM, Stanley MA, Petersen NJ, et al. Healthy IDEAS: A depression intervention delivered by community based case managers serving older adults. J Applied Gerontol. 2007;26:139–56.

Gitlin LN, Harris LF, McCoy M, et al. A community-integrated home based depression intervention for older African Americans: description of the Beat the Blues randomized trial and intervention cost. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:4.

Sheeran T, Lotterman J, Brown S, et al. Feasibility and impact of telemonitor-based depression care management for geriatric homecare patients. Telemed e-Health. 2011;17:620–6.

Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Sheeran T, et al. Depression care for patients at home (Depression CAREPATH): Protocols and implementation, Part 2. Home Healthc Nurse. 2011;29(8):480–9.

Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Reilly CG, et al. Developing and piloting a web-based, long-distance implementation strategy for depression care in home healthcare patients. Presented at the National Institutes of Health Dissemination and Implementation Conference. Washington DC; March 22, 2012.

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(1):4–23.

Institute of Medicine. The Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands? A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012.

Areán PA, Raue PJ, Sirey JA, Snowden M. Implementing evidence-based psychotherapies in settings serving older adults: Challenges and solutions. Psych Serv. 2012;63:605–7.

Acknowledgments

N.G. Choi, J. Sirey, and M.L. Bruce are supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Disclosure

N.G. Choi: none; J. A. Sirey: none; M.L. Bruce: compensation from McKesson, Inc. for serving as a consultant, and payment for lectures (including service on speakers’ bureaus) from Dartmouth Medical College.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, N.G., Sirey, J.A. & Bruce, M.L. Depression in Homebound Older Adults: Recent Advances in Screening and Psychosocial Interventions. Curr Tran Geriatr Gerontol Rep 2, 16–23 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-012-0032-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-012-0032-3

Keywords

- Homebound older adults

- Chronic illness

- Mobility impairment

- Mental health

- Depression

- Depression screening

- Psychosocial intervention

- Evidence-based psychotherapy

- Antidepressant medication

- Older Americans Act

- Aging service settings

- In-home services

- PHQ-9

- BSI-18

- Cognitive impairment

- Problem-solving therapy

- Telehealth delivery

- Behavioral activation

- PEARLS

- Healthy IDEAS

- Problem adaptation therapy

- Beat the Blues