Abstract

The current study relies upon the 2004 National Politics Study to examine the association between exposure to race-based messages within places of worship and White race-based policy attitudes. The present study challenges the notion that, for White Americans, religiosity inevitably leads to racial prejudice. Rather, we argue, as others have, that religion exists on a continuum that spans from reinforcing to challenging the status quo of social inequality. Our findings suggests that the extent to which Whites discuss race along with the potential need for public policy solutions to address racial inequality within worship spaces, worship attendance contributes to support for public policies aimed at reducing racial inequality. On the other hand, apolitical and non-structural racial discussions within worship settings do seemingly little to move many Whites to challenge dominant idealistic perceptions of race that eschews public policy interventions as solutions to racial inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is comparable to the median response rate (30 %) reported by Groves (2006) in his study of over 200 response rates in 35 published articles.

These measures were not combined in an additive index because of its low alpha score (0.554).

We recognize the limitation of dichotomously ordered variables aimed at measuring exposure to issue based discussions and sermons in houses of worship. While not excusing this limitation, we would like to point out that the discourse variables in this study are measured nearly identically to the way which these constructs have been measured by survey-based for nearly 50 years. The 1964 Negro Politics Study, the 1968 and 1969 Detroit Area Studies, 1997 Civic Involvement Study, studies commissioned by the Pew Charitable Trust, the Religion and Politics Studies of 1996 and 2000, and other large surveys all assess worship discourse in a nearly an identical manner as the National Politics Study.

We recognize that the alpha score for the racial discourse congregation index falls below the standard threshold of 0.7 for conducting indices. However, the results of the relationship between racial discourse congregation and race-based policy attitudes are nearly identical to what we find when we separately examine the relationship between exposure to race-based sermons and attending a congregation that hosts forums race relations with race-based policy attitudes. Furthermore, because the alpha score is partially based upon the number of items examined, it is quite plausible that our limited number items-2-impacts our alpha score. To that end, we utilize the current index for our study.

Religious Faith: This study relies upon Steensland et al.’s (2000) RELTRAD classification of religious faiths. This classification scheme is largely based upon the theology, political ideology, and racial backgrounds of varying religious adherents, and provides the best statistical fit in classifying religious groupings to date. This scheme is fairly consistent with the religious faith membership in national religious organizations, such as the National Council of Churches and the National Association of Evangelicals. Using the RELTRAD classifications, various Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran, Presbyterian, and Episcopalian denominations are grouped into Evangelical and Mainline Protestant traditions. The nominal categories of Catholic, Non-Christian, and the religiously unaffiliated are also included as faith traditions.

Missing values for worship attendance, age, and income are replaced by the Imputation by Chained Equations multiple imputation method on STATA 10. The imputed variables do not substantively or significantly change the outcomes of these analyses.

Although we did not display a table on the matter, we also examined the moderating role of religious denomination on the relationship between exposure to racial discourse in houses of worship and racial attitudes. Because we found no statistical difference in the interaction term, we did not include it in the manuscript. We also ran separate analyses for Mainline Protestants, Evangelical Protestants, and Catholics to determine if the relationship between exposure to race discourse and racial attitudes was substantively different among these groups; it was not. These analyses are available upon request.

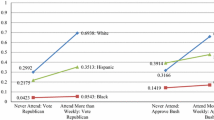

The probability estimates listed in Figs. 1 and 2 are derived from logit regression analyses that examine the likelihood of individuals supporting a race-based policy by the degree to which they attend racial discourse congregations while holding all of the control variables listed in Table 2 at their mean. The estimates for Figs. 1 and 2 are based upon the following formula; Pr(y = 1|\( \overline{\text{X}} \), max xk) − Pr(y = 1| \( \overline{\text{X}} \), min xk), in which Y represents Support for Job Preferences/Affirmative Action and X represents attending a racial discourse congregation.

References

Allen II, L.Dean. 2000. Promise keepers and racism: Frame resonance as an indicator of organizational vitality. Sociology of Religion 6I(1): 55–172.

Allen, Richard L., and Cheng Kuo. 1991. Communication and beliefs about racial inequality. Discourse & Society 2(3): 259–279.

Allport, Gordon W. 1979. The nature of prejudice: 25th anniversary edition. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Alumkal, Antony W. 2004. American evangelicalism in the post-civil rights era: A racial formation theory analysis. Sociology of Religion 65(3): 195–213.

Bartkowski, John P. 2004. The promise keepers: Servants, soldiers, and godly men. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Boff, Leonardo, and Clodovis Boff. 1987. Introducing liberation theology. New York: Orbis.

Brown, R.Khari, and Ronald E. Brown. 2003. Faith and works: Church-based social capital resources and African American political activism. Social Forces 82(2): 617–641.

Brown, R.Khari. 2009. Denominational differences in support for race-based policies among White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48(3): 604–615.

Brown, R.Khari. 2011. Religion, political discourse, and activism among varying racial/ethnic groups in America. Review for Religious Research 53(3): 301–322.

Brown, R.Khari, Angela Kaiser, and Anthony Daniels. 2010. Religion and the interracial/ethnic common good. Journal of Religion & Society 12: 1–12.

Cavendish, James C. 2004. A research report commemorating the 25th anniversary of Brothers and Sisters to Us. Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Inc. http://www.usccb.org/saac. Accessed 1 June 2012.

Djupe, Paul A., and Christopher P. Gilbert. 2008. The political influence of churches. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Edgell, Penny, and Eric Tranby. 2007. Religious influences on understandings of racial inequality in the United States. Social Problems 54(2): 263–288.

Eitle, Tamela McNulty, and Matthew Steffens. 2009. Religious affiliation and racial attitudes. Social Science Journal 46: 506–520.

Emerson, Michael O., and Christian Smith. 2001. Divided by faith: Evangelical religion and the problem of race in America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Green, John C., Robert P. Jones, and Daniel Cox. 2009. Faithful, engaged, and divergent: A comparative portrait of conservative and progressive religious activists in the 2008 election and beyond. Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics and Public Religion Research. (September) University of Akron, Akron, OH. http://www.uakron.edu/bliss/research/archives/2008/ReligiousActivistReport-Final.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2012.

Groves, Robert M. 2006. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. The Public Opinion Quarterly 70(5): 646–675.

Hinojosa, Victor J., and Jerry Z. Park. 2004. Religion and the paradox of racial inequality attitudes. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 229–238.

Jackson, James S., Vincent L. Hutchings, Ronald Brown, and Cara Wong. National Politics Study. 2004. [Computer file]. ICPSR24483-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2009-03-23. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR24483.

Jones, Jeffrey M. 2005. “Race, Ideology, and Support for Affirmative Action: Personal politics has little to do with blacks’ support.” The Gallup Poll. (August 23). Accessed on July 24, 2013 from http://www.gallup.com/poll/18091/race-ideology-support-affirmative-action.aspx.

Jones, Jeff and Lydia Saad. 2011. USA Today/Gallup Poll: August Wave 1—FINAL TOPLINE, August 4–7. http://www.gallup.com/poll/149087/Blacks-Whites-Differ-Government-Role-Civil-Rights.aspx. Accessed 1 June 2012.

Kluegel, James R., and Eliot R. Smith. 1981. Beliefs about stratification. Annual Review of Sociology 7: 29–56.

Kluegel, James R., and Eliot R. Smith. 1983. Affirmative action attitudes: Effects of self-interest, racial affect, and stratification beliefs on whites’ views. Social Forces 61(3): 797–824.

Kluegel, James R. 1985. If there isn’t a problem, you don’t need a solution”: The bases of contemporary affirmative action attitudes. American Behavioral Scientist 28(6): 761–784.

Kluegel, James R. 1990. Trends in Whites’ explanations of the Black-White Gap in socioeconomic status, 1977–1989. American Sociological Review 55(4): 512–525.

Kravitz, David A. 1995. Attitudes toward affirmative action plans directed at blacks: Effects of plan and individual differences. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 25(24): 2192–2220.

Lincoln, C.Eric, and Lawrence H. Mamiya. 1990. The black church in the African American experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

MOSES. 2012. M.O.S.E.S. Profile. http://www.mosesmi.org/profile.html. Accessed 15 June 2012.

Pattillo-McCoy, Mary. 1998. Church culture as a strategy of action in the black community. American Sociological Review 63: 767–784.

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. 2007. Optimism about black progress declines: blacks see growing values gap between poor and middle class. (November 13). http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/Race-2007.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2012.

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. 2009. Trends in political values and core attitudes: 1987–2009. (May 21). http://www.people-press.org/files/legacy-pdf/517.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2012.

Roozen, David A., William McKinney, and Jackson W. Carroll. 1984. Varieties of religious presence: Mission in public life. Hartford, CN: The Pilgrim Press.

Schuman, Howard, Charlotte Steeh, Lawrence D. Bobo, and Maria Krysan. 1998. Racial attitudes in America: Trends and interpretations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Steensland, Brian, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Robert D. Woodberry. 2000. The measure of American religion: Toward improving the state of the art. Social Forces 79(1): 291–318.

Summers, Russel J. 1995. Attitudes toward different methods of affirmative action. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 25(12): 1090–1104.

Swarts, Heidi J. 2008. Organizing urban America: Secular and faith-based progressive movements. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Taylor, Marylee C., and Stephen M. Merino. 2011. Race, religion, and beliefs about racial inequality. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 634: 60–77.

Tuch, Steven A., and Michael Hughes. 1996. Whites’ racial policy attitudes. Social Science Quarterly 77(4): 723–745.

Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry Brady. 1995. Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Verter, Bradford. 2002. Furthering the freedom struggle: Racial justice activism in the mainline churches since the civil rights era. In The quiet hand of god: Faith-based activism and the public role of mainline Protestantism, ed. Robert Wuthnow, and John H. Evans, 181–212. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

Warren, Mark. 2001. Dry bones rattling: Community building to revitalize American democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Warren, Mark, and Richard L. Wood. 2002. A different face of faith-based politics: social capital and community organizing in the public Arena. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 22(9/10): 6–54.

Wood, Richard L. 2002. Faith in action: Religion, race, and democratic organizing in America. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press.

Wuthnow, Robert. 2000. The Religion and Politics Study, 2000. Funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts. http://thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/RELPOL2000.asp.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khari Brown, R., Kaiser, A. & Jackson, J.S. Worship Discourse and White Race-Based Policy Attitudes. Rev Relig Res 56, 291–312 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-013-0139-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-013-0139-9