Abstract

Key message

Climate change is likely to heavily affect the provision of goods and services of Mediterranean forests. Our results strongly point out the need to develop adaptive strategies to mitigate the impact of climate change in order to assure the maintenance of the stands aiming their multifunctionality, more than their monetary revenues.

Context

Climate change in the Mediterranean region may heavily affect the provision of forest goods and services. Thus, options for adaptive forest management should be proposed.

Aims

The aims of this study are to analyze the climate-related sensitivity of Pinus pinea forests in the Northern Plateau in Spain and to assess the vulnerability of multiobjective forest management to climate change by means of a simulation study, focusing on timber and cone production.

Methods

The forest model PICUS v1.41, integrating a module for P. pinea cone and nut production, was used to simulate P. pinea stands at six site types under three forest management regimes (focus on timber, cones, and combined objectives) and five climate scenarios (current climate, four climate scenarios combining increases in temperature by +1 and +4 °C and decreases in precipitation by −10 and −30 %).

Results

Combined timber + cones management generated always the highest incomes from timber and cones. With the exception of the most productive site types, the combined timber + cone management produced also more timber volume than the cone and timber managements. Provisioning of ecosystem services decreased at all sites under all climate change scenarios. At very dry sites simulated, forests suffered from dieback events.

Conclusion

Provisioning of ecosystem services decreased at all sites under all climate change scenarios analyzed and will be extremely limited on poor sites. Benefits and weaknesses of the assessment approach are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Projected climatic changes in course of the twenty-first century will impact on forest ecosystems and affect the provisioning of ecosystem services. Mediterranean forests provide a diversity of goods (timber, firewood and mainly non-wood forest products such as pine nuts, cork, aromatic plants, game, mushrooms) but also high-value services (recreation, protection against erosion, livestock grazing, biodiversity conservation, CO2 sequestration, regulation of water balance) which are important to assure the well-being of human society. Multifunctionality is therefore a key characteristic of Mediterranean forest management.

Mediterranean forests are especially threatened by climate change (IPCC 2007; EEA 2012). The Mediterranean basin may be confronted to longer and more frequent droughts and heat waves, resulting potentially in forest dieback and mortality (Lindner and Calama 2013), decline in forest productivity (Nadal-Sala et al. 2013), and reduction in the production of valuable non-wood products (Mutke et al. 2005). Thus, the Mediterranean basin is likely to experience the most adverse effects of climate change in Europe, whilst being the least prepared to cope with such drastic impacts (Lindner and Calama 2013). In this context, it is important to understand the vulnerability of current management systems to climate change and to explore adaptation strategies in the Mediterranean forests (Masiero et al. 2013).

In this study, the focus is on Mediterranean stone pine (Pinus pinea L.), which is one of the most characteristic tree species in the Mediterranean because of its characteristic umbrella-shaped crown and the ancient use of its large, nut-like edible seeds for human consumption. It occupies more than 400,000 ha in Spain, both in inland and coastal regions (Calama et al. 2008), being the main tree species in sandy continental areas of central Spain, where water is the main limiting factor for forest production (Calama et al. 2013; Pardos et al. 2010). Economic benefits from P. pinea stands for the forest owner include edible pine nuts, timber, firewood, and grazing, whilst current management objectives also include social aspects such as recreational use, biodiversity conservation, soil protection against erosion, and CO2 fixation. From all these ecosystem services (ESs), cone production is currently the most profitable ES for the owners of stone pine forests, even higher than timber and other products (Ovando et al. 2010). For instance, the Spanish nut industry has a share of about 45 % in total world pine nut production (Mutke et al. 2000). Nevertheless, cone production is limited by site quality, stand stocking, and masting habit (which is mainly triggered by weather conditions during cone development; Calama et al. 2008) and subordinated to the ecological and social functions of these forests (Mutke et al. 2005).

Currently, the sandy flatlands of inner central Spain are the genuine habitats for stone pine, with very few tree species being able to grow at such highly permeable sites (Sanchez-Palomares et al. 2013). However, this is one of the most limiting regions in terms of precipitation that defines the lower xeric limit for species survival. Thus, planned adaptation measures in the management of Mediterranean P. pinea forests need to address especially the main climate change threat in the region which is severe summer drought. In meeting this challenge, process-based forest ecosystem models can help to assess impacts and to design management strategies (Seidl et al. 2011). Different model-based climate change vulnerability assessments are available for temperate and boreal regions (e.g., Lexer et al. 2002; Seidl et al. 2005; Briceño-Elizondo et al. 2006) and Mediterranean regions (e.g., Sabaté et al. 2002; Rathgeber et al. 2003). Currently, there is a growth and yield model available which has been specifically developed for P. pinea (PINEA v.2, Calama et al. 2007) that also projects the masting pattern of the species, but which does not tackle changing climatic conditions. To circumvent these shortcomings and to address the climate-related vulnerability of P. pinea forests, we used the hybrid forest patch model PICUS v.1.41 (e.g., Seidl et al. 2005) which has been extended by a cone and nut production submodule for P. pinea (Calama et al. 2011).

The main objectives of this paper are to analyze the climate-related sensitivity of P. pinea forests in the Northern Plateau and to assess the vulnerability of multiobjective forest management to climate change by means of a simulation study. Our particular aims were as follows: (i) to calibrate and validate the process-based model PICUS v1.41 for predicting stand dynamics of P. pinea forests under climate change, (ii) to evaluate the provision of the ESs assessed (timber, cone productivity and carbon sequestration) from the P. pinea stands under the current (baseline) climate, and (iii) to analyze the potential impacts of climate change and forest management on stand development and on the related ES.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study material

2.1.1 Study area

The study was conducted in the Northern Plateau (province of Valladolid, central Spain, Fig. 1), where P. pinea is the main tree species. It occupies more than 50,000 ha in pure even-aged stands. The landscape is characterized by a smooth orography at the western and southern parts and at the north and eastern parts of the province. From geomorphological perspective, two strata can be distinguished: the flat sedimentary basin of the river Duero (“sandy lands”) and the limestone plateaus which are remains of non-eroded calcareous hills. The climate is Mediterranean continental characterized by comparably cold and long winters (mean annual temperature 12.2 °C, minimum mean temperature of the coldest month (i.e., January) is −0.5 °C), short but hot and dry summers (maximum mean temperature of warmest month (July) is 30.7 °C, 20 mm of precipitation on average between July and September) and moderate but irregularly distributed rainfalls (annual rainfall 440 mm, ranging between 250 and 700 mm).

2.1.2 Site types

Based on a site stratification scheme by Calama et al. (2003), six site types (ST1 to ST6) were distinguished for the assessment (Table 1). For ST1, upwelling of water from the ground water table into the root horizon has been considered (Calama et al. 2003). Site types include, inter alia, poor to medium fertility sites with acidic-neutral pH and low water holding capacity due to 85–90 % sand content in soil texture (ST2, ST3, ST4) and alkaline soils of medium fertility which are relatively shallow but have a considerable content of clay and, subsequently, medium to high water holding capacity (ST5, ST6).

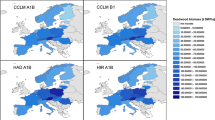

2.1.3 Climate data

To assess the vulnerability to climate change conditions, five different climate data sets were prepared to drive the forest model. Data set for the baseline climate (C1) is a detrended stochastic time series of monthly mean temperature, precipitation, vapor pressure deficit (VPD), and global radiation over the 120-year simulation period. The baseline climate was generated from available daily instrumental data for the period 1973–2010 from a nearby meteorological weather station (735 m a.s.l.; X: 4° 45′ 16″ W; Y: 41° 38′ 27″ N). VPD values were calculated from daily minimum, mean, and maximum temperatures, relative humidity, radiation from day length, temperature, and humidity data and aggregated to monthly values. Based on the scenarios compiled by the ENSEMBLES project (Hewitt and Griggs 2004) that show, for central Spain, increases in mean annual temperature of +3 to +6.5 °C and, for precipitation, changes from −25 to −50 %, the data sets C2 to C5 were constructed by combining to the baseline climate changes in temperature (+1, +4 °C) and precipitation (−10, −30 %) to represent a range of climate projections for the twenty-first century (IPCC 2007): C2 (+1 °C, −10 % P), C3 (+1 °C, −30 % P), C4 (+4 °C, −10 % P), and C5 (+4 °C, −30 % P).

2.2 Assessment approach

2.2.1 PICUS v1.41

The main tool for the assessment of climate-related vulnerability of P. pinea stands in this study is an extended version of the hybrid forest patch model PICUS v1.41 (Seidl et al. 2005). The model PICUS combines components of a 3D gap model (Lexer and Hönninger 2001) with a process-based production model. Spatial frame of the simulation is a 10 × 10-m2 patch array extended into the z-dimension by 5 m crown cells. Spatial interactions between the patches are considered via a detailed three-dimensional model of the light regime and spatially explicit seed dispersal. Stand-level primary production is expressed as a function of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation. Carbon gain is redistributed from stand level to the individual trees according to their relative competitiveness within the stand. Tree mortality considers competition-induced resource limitations for individual trees, environmental stress (e.g., water, temperature), and chance events (Seidl et al. 2011). PICUS v1.41 also includes a flexible management module. The model requires monthly input of temperature, precipitation, radiation, and VPD (see Lexer and Hönninger (2001) and Seidl et al. (2005) for a detailed description of the model). PICUS offers a detailed projection of stand dynamics under the simulated management and climate conditions, including individual-tree information such as diameter, height, and volume.

2.2.2 A cone and nut production submodule for P. pinea

An additional module for P. pinea cone and nut production based on Calama et al. (2011) has been integrated into PICUS. This module predicts annual cone and seed production at tree level taking into account climate (e.g., precipitation and freezing events) during the 4-year period that is relevant for the development of the cones (reproductive bud differentiation in year 0, flowering and pollination in year 1, cone development during year 2, fecundation and cone maturation in year 3, and cone opening and subsequent seed dispersal in year 4), together with site attributes, maturity of a tree, stand stocking, competition by other trees, and tree size. The module follows a two-stage approach, predicting, first, the probability (π) that a tree bears cones in a given year and, second, the seed production of the tree, conditional to the occurrence of a cone crop for that tree and year (see Appendix 1 for details on the cone model).

2.3 P. pinea calibration and model validation

PICUS v1.4 has been parameterized, evaluated, and applied to questions of sustainable forest management under climate change in a broad set of temperate and alpine central European tree species (e.g., Lexer and Hönninger 2001; Seidl et al. 2005 and 2011). P. pinea has not been present in former tree species sets and applications. Based on a thorough literature review focusing mainly on physiological ecology of P. pinea and biometric information on height (Calama et al. 2003) and diameter growth (Calama and Montero 2005) as well as biomass allometries (Ruiz-Peinado et al. 2011), species parameters related to the key ecosystem processes growth, mortality, and reproduction have been defined (for details on the calibration procedure see http://picus.boku.ac.at/doku.php?id=calibration).

The model setup has been checked for plausibility of simulated growth and mortality behavior by simulating generic mono-species stands along environmental gradients from dry and poor to moist and rich sites. The simulations were initialized from thicket stage and run over 200 years without management interventions. The response of volume production and stand height growth to site conditions as well as emerging height-diameter relationships in the simulated stands were compared with available information from the literature (e.g., Montero et al. 2004). To test the settings for tree mortality during the stem exclusion phase, the simulated self-thinning process was compared to the theoretical self-thinning model based on the 3/2 power law (Zeide 1987) while in later stand development stages, tree mortality is at very low levels unless harsh environmental conditions exceed the tolerance limits of P. pinea. In these evaluation runs, model behavior was consistent with literature.

Model output was also compared to long-term observational data from 12 long-term monitoring plots with an average size of 2000 m2 located within the study region (see Fig. 1). The plots were installed in 1966 and have been measured four times (1966-71-81-90). At each plot, DBH of all trees and height of 40 trees per plot were measured. All the plots represent pure, even-aged P. pinea stands, and cover broad age and site gradients (Table 2). Available information from soil surveys in course of the inventories was used to link the plots to the site stratification system by Calama et al. (2003). For the validation runs, the management interventions on the plots (defined by removed stem numbers per ha) as recorded by the inventories were mimicked with PICUS v1.41. The 25-year inventory time span was simulated using the historic climate record as model driver and considering the historic management interventions. For each plot, the simulated values for mean DBH, basal area, mean and dominant stand height, and standing volume stock were compared to the observed values from the recent remeasurement in 1990. The matches between observed and predicted values were analyzed by means of mean error, modeling efficiency, root-mean-square error, and relative error (average value of mean error divided by observed value). Together with this, a linear regression was fitted between the observed and predicted values for each variable, and independent t tests were employed to evaluate whether the intercept = 0 and slope = 1.

2.4 Simulation experiments

2.4.1 Management alternatives

P. pinea forests in the Northern Plateau have had a multifunctional management history since the end of the nineteenth century. These forests have been traditionally managed in pure even-aged stands in order to jointly enhance cone and timber production, although uneven-aged mixed structures have been also proposed recently. Traditional even-aged stand management in P. pinea is based on shelterwood systems (Gordo et al. 2012). Three management regimes are currently practiced in naturally regenerated P. pinea stands, here denoted as timber production (TP), cone production (CP), and a combination of timber and cone production (CTP). These alternatives differed in the rotation length, type, and time of thinning and stocking density (Table 3). All three alternatives start not only with a tending operation to reduce and to homogenize the stand density to 600 stems ha−1 (when dominant height reaches 3 m, at stand ages between 8 and 23 depending on site quality), but also as a preventive measure against forest fires. Management for TP is based on a relatively short rotation length and delayed and less-intensive thinnings. Management for CP focuses on early and heavy thinnings, promoting trees with large crowns in order to increase the individual tree CP, and extended rotations over 120 years. The combined timber and cone (CTP) management schedule is meant to be a combination of the two former approaches. All the schedules propose to regenerate the stand following a uniform shelterwood approach that includes four fellings during a 20-year regeneration period, leaving four to five large trees per hectare at the end of the rotation for biodiversity purposes (Table 3).

2.4.2 ES indicators

The analyzed ESs in this study are carbon storage, timber, and cone production. TP over the full rotation was assessed by mean annual increment (sum of harvested volume + natural tree mortality + standing volume at the end of the rotation period, divided by rotation length; average annual increment in total volume (MAI), in m3 ha−1 year−1) and mean harvested volume of saw logs during the rotation period (MHsaw, in m3 ha−1 year−1). Timber volume is merchantable volume under bark where three-dimensional assortments are distinguished: saw timber for logs with end diameter >35 cm, pulp wood for logs with end diameter between 10 and 35 cm, and fuel wood for logs with end diameter <10 cm.

CP was assessed as annual average CP per hectare (CPha, in kg ha−1 year−1) and per tree (CPtree, in kg tree−1 year−1). In addition, we calculated the equivalent annual income (EAI) of cash flows from harvested timber and cropped cones as the annualized net present value (NPV) employing stumpage prices for cones (0.3€ per kg) and timber assortments (12.5€ per m3 for pulp, 17.5€ per m3 for saw logs, 8.1€ per m3 for fuel wood) and an interest rate (p) of 4 % (Eqs. (1) and (2)). Costs of management are covered by the governmental administration and have not been included in the calculations. Thus, EAI represents the current landowner perspective.

where U is the rotation period and t is the year (from 1 to U)

The carbon pool in living trees (stem, branches, needles, carbon storage (CS)) in kilogram C per hectare was considered as indicator for carbon sequestration.

2.5 Experimental setup

The PICUS model was employed to simulate each of the three management regimes (Table 3) at the six site types (Table 1) under the baseline climate as well as under four climate change scenarios over a full rotation. The development of stem number and volume stock was used to evaluate the persistence of P. pinea stands. ANOVAs were used to identify significant main effects of climate scenarios, site types, and management alternatives on ES provisioning as well as their first-order interactions (SAS v. 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Vulnerability of ES provision to climatic changes was evaluated by analyzing the sensitivity of the studied variables relative to the baseline climate C1 (i.e., the ratio between the expected values under baseline conditions and under the different climate change scenarios).

3 Results

3.1 Model validation

Comparing simulated dominant and mean stand height, basal area, mean diameter, and standing volume with independent observed data from 12 long-term monitoring plots yielded promising results (Fig. 2). Modeling efficiency (ME; analogous to R 2 statistics for linear regression) for the five variables was between 50 and 70 %, indicating good agreement of predictions and observations. The model produced unbiased estimates (p value >0.01) for all variables. For basal area and mean DBH, there was a slight tendency of the model to underestimate. Relative error was below 13 % for all the studied variables. Results from the t tests to evaluate the assumptions of an intercept = 0 and a slope = 1 in the linear regression of observed versus predicted values were not significant. Thus, the null hypothesis of equality could not be rejected for all the analyzed variables. In addition, the CP model from Calama et al. (2008, 2011) was successfully integrated within PICUS. The sensitivity of the CP model to short-term climate conditions is shown in Fig. 3.

3.2 Stand persistence under climate change

P. pinea stands on site types ST3 and ST4 are severely threatened under climate scenarios with 30 % decrease in precipitation (C3 and C5). For instance, the climate scenario C5 resulted in severe tree mortality in sandy soils of site type ST3 when managed under the TP management regime and on site types ST3 and ST4 under any management regime. Similar results emerge under climate scenario C3 at site type ST4 under mixed objective management (CTP). Thus, simulations indicate that local die-off phenomena are to be expected especially in sandy soils mainly due to the direct effect of the 30 % reduction in rainfall in combination with a large increase in temperature. On better site types, tree populations could be maintained in the simulations, although growth was negatively affected under all climate change scenarios.

3.3 Provision of ES under baseline climate

Over a rotation period, the ANOVA showed a significant effect of site type and management regime for natural timber (MAI) and CP indicators and CS. However, the management alternatives did not differ significantly in the accumulated monetary income indicator EAI which was only affected by site type (Table 4). Simulations showed the highest production in terms of timber (MAI = 2.97 m3 ha−1 year−1) and cones (CPha = 333.2 kg ha−1 year−1) and also the highest income (EAI = 862.4 €) on site type ST1, followed by ST5 (MAI = 2.01 m3 ha−1 year−1, CPha = 174.6 kg ha−1 year−1, EAI = 484.0 €) with the lowest values occurring on site type ST4 (MAI = 0.52 m3 ha−1 year−1, CPha = 9.2 kg ha−1 year−1, EAI = 91.8 €). This confirms the productivity ranking of the site types based on empirical site index information (Montero et al. 2008).

Cone-oriented management significantly improved the individual tree production (p value < 0.0001), although no differences between CP and CTP management regimes were found for mean CP per hectare. As expected, TP is promoted not only by TP management, but also by the combined CTP management regime. The CP regime has very strong thinnings which negatively affected overall TP. However, when the main interest is in saw logs, the CP and CTP management regimes outperform the TP regime as these treatments strongly promote the growth of a relatively small number of dominant trees. Related to this, timber management (TP) under current climate (C1) in site types ST3 and ST4 produces very low cone crops (25 kg cones ha−1 year−1 and 4.7 kg cones ha−1 year−1, respectively). CP on the other site types under the TP regime varies between 62 kg cones ha−1 year−1 in ST6 and 265 kg cones ha−1 year−1 in ST1.

3.4 Vulnerability of ES provision under climate change conditions

Timber and CP, CS, and annual income responded sensitive to the climate change scenarios C2–C5 and are lower under any of the analyzed management regime at all sites when compared to results under baseline climate (Fig. 4). Particularly severe is the response under the 30 % decrease in precipitation in scenarios C3 and C5 with a mean reduction of 78 % in EAI and CS (Table 5). CP dropped by 95 % which, particularly at ST3 and ST4, does not just diminish profitability of forest management but renders natural regeneration of P. pinea impossible (mean CP over all sites is 14 kg ha−1 year−1). The annual income (EAI) decreased between 38 % under climate scenarios C2 (260.5 € ha−1 year−1) and 44 % under C4 (244.7 € ha−1 year−1) and between 69 % under climate scenario C3 (121.8 € ha−1 year−1) and 78 % under C5 (88.3 € ha−1 year−1), when compared to the baseline climate C1 (423.2 € ha−1 year−1). The average decrease in CP (CPha) under climate change conditions (C2, 53 %; C3, 91 %; C4, 53 %; C5, 95 %) is more dramatic than the average decrease in TP (MAI) (C2, 12 %; C3, 44 %; C4, 28 %; C5, 73 %).

The significant interaction of site type and climate shows that climate change impacts will be intensified on poor sites (Fig. 5). Though the management regime is a significant factor for all indicators except EAI, interaction is significant neither with site type nor with climate. Interestingly, the timber management regime (TP) shows always the higher decrease in TP (44 % decrease in MAI), CP (69 % decrease), and CS (51 % decrease), compared to cone management (CP) and the mixed cone and timber management (CTP; see Table 5 and Fig. 4).

4 Discussion

4.1 Calibration of the forest model PICUS

The available knowledge on ecology and growth of P. pinea is well developed, and estimating the relevant model parameters for that species imposed no major difficulties. This was reflected by the results of the model evaluation exercises. In PICUS, biomass production emerges as a result of the interplay of soil attributes, climate, and vegetation structure. In view of uncertainty in the estimates for soil water storage capacity and available nitrogen alone, the correspondence between a set of simulated target variables (dominant and mean stand height, mean diameter at breast height, basal area, and volume) and corresponding observations from long-term monitoring plots can be considered as excellent. This set of variables characterizes stand structure very well, and the fact that all five variables were consistently projected over 25 years indicates that the production and allocation processes in P. pinea stands have been well captured. The CP model from Calama et al. (2008, 2011) was successfully integrated within PICUS. Interfaces were clearly defined and fitted well to the internal structure and processes of PICUS. The CP model is climate dependent, thus highly sensitive to short-term changes in climate conditions, mainly to spring and fall precipitations (see Fig. 3,). The CP model also includes the site index (SI) as predictor variable. SI is a cumulative indicator of stand growth integrating height development of a stand over several decades depending on the SI system used. As such SI is inherently based on the assumption of stable site conditions, the use of SI under transient climate change conditions would have been therefore problematic. This supports the use of climate scenarios which do not include temporal trends in temperature and precipitation over the 120-year simulation period. In our analysis, SI under the climate scenarios C2–C5 had been estimated in simulation runs prior to the full simulation experiment for the vulnerability assessment.

The flexibility of the management module of PICUS allowed to realistically implement and to simulate the pine management regimes. The PICUS version for P. pinea provides, for the first time, the opportunity to analyze climate change-related vulnerability of ES provisioning from stone pine forests in Spain.

4.2 Provision of ES from P. pinea forests in the Northern Plateau

Under the baseline climate, the suitability of each site and alternative management affected CS, cone, and timber production. Values in timber and CP obtained from the simulations under current climate are in the range of the values recorded for the species in the Northern Plateau (Montero et al. 2008). High-quality stands (ST1 and ST5) showed high CS capacity and high productivity; however, on low-quality sites (ST4), productivity decreased drastically. Overall, the CP management regime moderately increased CS (1.6-fold) and annual average CP (1.7-fold) and greatly increased volume of saw logs at final harvest (3.9-fold) compared to the TP management. Interestingly, the mixed cone and timber management regime proved very efficient regarding average annual volume increment over the rotation period. Obviously, the standard TP regime is too passive regarding density control and promotion of socially dominant trees in a stand. Another factor to take into consideration is that, in natural stone pine forests, many trees (30–80 % in any year) do not bear any cones and nearly 10 % of the pines never produce cones. Factors such as stand age, high stocking densities, soils with low water-holding capacity, and dry conditions increase the proportion of trees with null crops (Calama et al. 2011).

Simulations over the rotation period under the baseline climate show that stone pine would generate different annual incomes (expressed as EAI) from timber and cones according to the natural suitability of each site and the applied management. Site type ST1, which benefits from uptake of water via the water table yielded the highest incomes. At ST5 and ST6, the higher clay content and, related to this, the better water supply increased the productivity of these stands (Calama et al. 2008). In contrast, the low-quality stands on sandy soils (ST4) have such low annual incomes that any other agricultural crop will likely be more profitable for the landowners. For instance, at these sites, from the perspective of income generation, traditional P. pinea stands can hardly compete with dryland cereal fields (Mutke et al. 2000), which is the preferred choice for farmers, even with government incentives for afforestation (Ovando et al. 2010).

In stone pine-dominated forests, cones and pine nuts are currently the economically most important products, providing a higher income to the forest owners than timber and other products (Ovando et al. 2010). However, two issues should be considered when discussing monetary revenues in stone pine stands managed only for CP. First, average CP varies greatly in time (due to the masting habit of the species, mainly ruled by climate conditions) and in space (related to site quality, soil water holding capacity, stand maturity, and stocking) (Calama et al. 2008; Mutke et al. 2005). Second, cone stumpage prices are subject to huge interannual variations that would have a negative effect on the profitability of these stands (Ovando et al. 2010). Thus, based on these considerations and the results of the current analysis, a mixed cone and timber management seems to be the most promising economic alternative to the landowners when only market goods and services are considered.

However, beside the economic owner interests, the multifunctionality of Mediterranean forests where recreation, carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, soil protection against erosion, and water regulation are high-value services (Masiero et al. 2013) needs special consideration.

4.3 Are stone pine stands viable in the Northern Plateau in the long term?

Many studies identify the Mediterranean, in general, and the Northern Plateau, in particular, as a climate change hotspot for the coming years (Masiero et al. 2013; Spathelf et al. 2014). Our study agrees with others (e.g., Bravo-Oviedo et al. 2010; Nadal-Sala et al. 2013; Lindner and Calama 2013) that, under climate change, the productivity of Mediterranean forests will severely decline mainly due to temperature increases during the summer and intensified drought periods. Particularly severe will be the decrease in the provision of the analyzed ES under a 30 % decrease in precipitation (climate change scenarios C3 and C5), which will be a realistic scenario based on the recent climate change projections for the Mediterranean region (Lindner and Calama 2013). For instance, average summer temperatures are projected to increase between 3.4 and 5.1 °C, while summer precipitation will be reduced between 28 and 51 % in the Mediterranean area (Lindner and Calama 2013). Such future climatic conditions will convert Mediterranean forests in sources rather than sinks for carbon dioxide (Sabaté et al 2002).

In our simulations, the reduction of 30 % in precipitation (scenarios C3 and C5) triggered stand mortality, mainly in low-quality sites on sandy soils (ST3 and ST4), for all currently practiced management alternatives. Local die-off processes in less-productive areas have already been identified for stone pine forests in the Central Range of Spain (Lindner and Calama 2013; Spathelf et al. 2014). This effect will be aggravated by the predicted failure on natural regeneration for the species under drier conditions (Manso et al. 2014). For instance, our simulations predict a 95 % drop in CP that will not only affect the profitability of these stands, but also greatly limit natural regeneration. Previous findings result in an expected substitution of stone pine by more xeric species (Felicisimo 2011). However, on the Northern Plateau, severely limited soil water supply at sites with high sand content in the soil prevents the substitution by other species such as Quercus ilex. Thus, in these locations, P. pinea is the last stage of tree vegetation, resulting in expected losses not only of monetary revenues but also of essential ES such as protection against soil erosion. On the other hand, at better sites, P. pinea is expected to displace Pinus pinaster (Ledo et al. 2014), which is another Mediterranean pine with high vulnerability to climate change (Bravo-Oviedo et al. 2010). For instance, by 2080, P. pinaster is expected to reduce its site quality by 1–2 SI classes in the less-productive areas in the south of Spain (Lindner and Calama 2013).

For the region represented by our analysis, the results point out the need to develop adaptive management strategies to assure the maintenance of ES provisioning. Particularly at sandy sites with low productivity, soil protection is of higher importance than monetary revenues for the landowner. In these site types, representing more than 25 % of the total area of stone pine distribution in the Northern Plateau, particular attention should be drawn in developing adaptive strategies to climate change. In these stands, adaptation and conservation strategies through silvicultural ractices such as early and heavier thinnings to reduce water losses through evapotranspiration and introduction of more resistant provenances (García-Güemes and Calama 2014) are potential options to maintain a minimum of ES provisioning in the future (Mazza et al. 2014). The need to adapt management strategies to expected changes in climate will be very important to sustain the functioning of Mediterranean forest, especially to overcome severe periods of drought and high temperatures (Sabaté et al. 2002).

References

Bravo-Oviedo A, Gallardo-Andrés C, Del Río M, Montero G (2010) Regional changes of Pinus pinaster site index in Spain using a climate-based dominant height model. Can J For Res 40:2036–2048

Briceño-Elizondo E, Garcia-Gonzalo J, Peltola H, Kellomäki S (2006) Carbon stocks in the boreal forest ecosystem in current and changing climatic conditions under different management regimes. Environ Sci Policy 9:237–252

Calama R, Montero G (2005) Multilevel linear mixed model for tree diameter increment in stone pine (Pinus pinea L.): a calibrating approach. Silva Fennica 39(1):37--54

Calama R, Cañadas N, Montero G (2003) Inter-regional variability in site index models for even-aged stands of Stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) in Spain. Ann For Sci 60:259–269

Calama R, Sánchez-González M, Montero G (2007) Management oriented growth models for multifunctional Mediterranean forests: the case of the stone pine (Pinus pinea L.). In: Palahí M, Birot Y, Rois M (eds) Scientific tools and research needs for multifunctional Mediterranean forest ecosystem management. EFI Proceedings no. 56:57–68

Calama R, Mutke S, Gordo J, Montero G (2008) An empirical ecological-type model for predicting Stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) cone production in the Northern Plateau (Spain). For Ecol Manag 255:660–673

Calama R, Mutke S, Tomé J, Gordo J, Montero G, Tomé M (2011) Modelling spatial and temporal variability in a zero-inflated variable: the case of stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) cone production. Ecol Model 222:606–618

Calama R, Puértolas J, Madrigal G, Pardos M (2013) Modeling the environmental response of leaf net photosynthesis in Pinus pinea L. natural regeneration. Ecol Model 251:9–21

EEA (European Environmental Agency) (2012) Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2012. EEA Report No 12/2012

Felicísimo ÁM (coord.) (2011) Impactos, vulnerabilidad y adaptación al cambio climático de la biodiversidad española. 2. Flora y vegetación. Oficina Española de Cambio Climático, Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino. Madrid, 552 p

García-Güemes C, Calama R (2014) La práctica de la selvicultura para la adaptación al cambio climático. In: Zavala MA (eds) Estrategias de Adaptación y casos prácticos. In press

Gordo J, Calama R, Pardos M, Bravo F, Montero G (eds) (2012) La regeneración natural de Pinus pinea L. y Pinus pinaster Ait. en los arenales de de la Meseta Castellana. IUGFS. ISBN: 978-84-615-9823-6. 254 pp

Hewitt CD, Griggs DJ (2004) Ensembles-based predictions of climate changes and their impacts (ENSEMBLES). EOS Trans Am Geophys Union 85:566. doi:10.1029/2004EO520005

IPCC Climate Change (2007) The physical science basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ledo A, Cañellas I, Barbeito I, Gordo FJ, Calama R, Gea-Izquierdo G (2014) Species coexistence in a mixed Mediterranean pine forest: spatio-temporal variability in trade-offs between facilitation and competition. For Ecol Manag 322:89–97

Lexer MJ, Hönninger K (2001) A modified 3D-patch model for spatially explicit simulation of vegetation composition in heterogeneous landscapes. For Ecol Manag 144:43–65

Lexer MJ, Hoenninger K, Scheifinger H, Matulla C, Groll N, Kromp-Kolb H, Schadauer K, Starlinger F, Englisch M (2002) The sensitivity of Austrian forests to scenarios of climatic change: a large-scale risk assessment based on a modified gap model and forest inventory data. For Ecol Manag 162:53–72

Lindner M, Calama R (2013) Climate change and the need for adaptation in Mediterranean forests. In: Lucas-Borja NE (ed) Forest Management of Mediterranean forests under the new context of climate change. Building alternatives for the coming future. Nova Science Pub.: 13–30

Manso R, Pukkala R, Pardos M, Miina J, Calama R (2014) A multistage stochastic regeneration model for Pinus pinea in the Northern Plateau. Can J For Res. doi:10.1139/cjfr-2013-0179

Masiero M, Calama R, Lindner M, Pettenella D (2013) Forests in the Mediterranean region. In: Lucas-Borja NE (ed) Forest management of Mediterranean forests under the new context of climate change. Building alternatives for the coming future. Nova Science Pub.: 3–12

Mazza G, Cutini A, Manetti MC (2014) Site-specific growth responses to climate drivers of Pinus pinea L. tree rings in Italian coastal stands. Ann For Sci. doi:10.1007/s13539-014-0391-3

Montero G, Candela JA, Rodríguez A (2004) El pino piñonero (Pinus pinea L.) en Andalucía. Junta de Andalucía. 261 p

Montero G, Calama R, Ruiz-Peinado R (2008) Selvicultura de Pinus pinea L. In: Serrada R, Montero G, Reque JA (eds) Compendio de Selvicultura aplicada en España, INIA, Fundación Conde del Valle de Salazar, 1178 p

Mutke S, Díaz-Balteiro L, Gordo J (2000) Análisis comparativo de la rentabilidad comercial privada de plantaciones de Pinus pinea L. en tierras agrarias de la provincia de Valladolid. Inv Agr Sist Rec For 9:269–303

Mutke S, Gordo J, Gil L (2005) Variability of Mediterranean stone pine cone yield: yield loss as response to climate change. Agric For Meteorol 132:263–272

Nadal-Sala D, Sabaté S, Gracia C (2013) GOTILWA+: un modelo de procesos que evalúa efectos del cambio climático en los bosques y explora alternativas de gestión para su mitigación

Ovando P, Campos P, Calama R, Montero G (2010) Landowner net benefit from Stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) afforestation of dry-land cereal fields in Valladolid, Spain. J For Econ. doi:10.1016/j.jfe.2009.07.001

Pardos M, Puértolas J, Madrigal G, Garriga E, de Blas S, Calama R (2010) Seasonal changes in the physiological activity of regeneration under a natural light gradient in a Pinus pinea regular stand. For Syst 19:367–380

Rathgeber C, Nicault A, Kaplan JO, Guiot O (2003) Using a biogeochemistry model in simulating forests productivity responses to climatic change and CO2 increase: example of Pinus halepensis in Provence (south-east France). Ecol Model 166:239–255

Ruiz-Peinado R, Montero G, del Río M (2011) New models for estimating the carbon sink capacity of Spanish softwood species. For Syst 20:176–188

Sabaté S, Gracia CA, Sánchez A (2002) Likely effects of climate change on growth of Quercus ilex, Pinus halepensis, Pinus pinaster, Pinus sylvestris and Fagus sylvatica forests in the Mediterranean region. For Ecol Manag 162:23–37

Sanchez-Palomares O, López-Senespleda E, Calama R, Ruiz-Peinado R, Motenro G (2013) Autoecología paramétrica de Pinus pinea L. en la España peninsular. Monografias INIA: serie forestal 26. INIA. Madrid, 305 pp

Seidl R, Lexer MJ, Jäger D, Hönninger K (2005) Evaluating the accuracy and generality of a hybrid patch model. Tree Physiol 25:939–951

Seidl R, Rammer W, Lexer MJ (2011) Climate change vulnerability of sustainable forest management in the eastern Alps. Climate Change 106:225–254

Spathelf P, Van Der Maaten E, Van Der Maaten-Theunissen M, Campioli M, Dobrowolska D (2014) Climate change impacts in European forests: the expert-views of local observers. Ann For Sci 71:131–137

Zeide B (1987) Analysis of the 3/2 power law of self-thinning. For Sci 33(2):517--537

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the projects AGL2010-15521, AT2010-007, S2009AMB-1668, RTA2013-00011-C02-00, and the EU FP7 project ARANGE-289437.

Funding

This study was financed by the projects AGL2010-15521, AT2010-007, S2009AMB-1668, and the EU FP7 project ARANGE- 289437. Project S2009AMB-1668 and the EU FP7 project ARANGE-289437 financed M. Pardos a two one-week stay to discuss the results at BOKU. M. Pardos was funded with a 2-month STSM with Cost Action FP0703 to work in the calibration and validation of PICUS and to run the model.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling Editor: Lluis Coll

Contributions of the co-authors

M. Pardos and R. Calama designed the experiments, defined the alternative managements and ES to analyze, and ran the data analysis. R. Calama provided data for calibration and validation of the forest PICUS model and for the integration of the PINEA submodule. M. Maroschek helped M. Pardos running PICUS, under M.J. Lexer supervision. W. Rammer prepared the climate data sets to drive PICUS and implemented the PINEA submodule into PICUS. M. Pardos wrote the manuscript, supervised by R. Calama and M.J. Lexer.

Appendix 1. Model for annual cone production

Appendix 1. Model for annual cone production

where ppjn3 is the May to June precipitation (mm) in the year previous to flowering; ppon3 is the October to November precipitation (mm) in the year previous to flowering; ppjas2 is the precipitation (mm) in the summer (July to September) after flowering; ppfmam0 is the February to May precipitation (mm) in the year of cone maturation; nfr is the number of days with frost (minimum temperature below −5 °C) during the first winter after flowering; N is the stand density (stems ha−1); SI is the site index (m); T 20 and T 50 are the categorical variables, with value of 1 when stand age is <20 or 50 years old, respectively, and 0, for the rest; d/dg is the quotient between dbh (d, in cm) and quadratic mean diameter (dg, in cm); and NU1 and NU2 are the parameters characterizing subregions within the Northern Plateau.

Provision of timber production and cone production over the rotation period. The horizontal lines are the indicator value under baseline climate (C1), the vertical whisker represents min/max indicator values under climate change scenarios C2–C5, and the symbol on the vertical whiskers is the mean value under C2–C5. MAI mean annual volume increment, EAI Timber equivalent annual income from timber production, CP cone production, EAI Cones equivalent annual income from cone production, CP cone production, TP timber production, CTP combination of timber and cone production

Interaction plots between climate and site type for the sensitivity value (estimated value for climate scenarios (C2 to C5) divided by the estimated value for the baseline climate, C1) of a carbon storage (CS), b mean annual volume increment (MAI), c annual average cone production per ha (CPha), and d annual average cone production per tree (CPtree). C2/C1  , C3/C1

, C3/C1  , C4/C1

, C4/C1  , C5/C1

, C5/C1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pardos, M., Calama, R., Maroschek, M. et al. A model-based analysis of climate change vulnerability of Pinus pinea stands under multiobjective management in the Northern Plateau of Spain. Annals of Forest Science 72, 1009–1021 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-015-0520-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-015-0520-7

, ST2

, ST2  , ST3

, ST3  , ST4

, ST4  , ST5

, ST5  , ST6

, ST6