Abstract

• Background

Production of seedlings, especially in containers, requires simultaneous germination and emergence. Mechanical scarification often speeds up the growth of embryo axes, increases the percentage of germinating seeds and seedling emergence. Cutting off the distal ends of cotyledons is a mechanical scarification technique sometimes used in the container production of oak seedlings. However the consequences of this procedure for seedling development are little known. We wanted to determine these effects on development and metabolic changes of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) seedlings.

• Results

The majority of seedlings from acorns with cut cotyledons emerged two weeks earlier, more simultaneously and their total emergence (due to rejecting spoiled acorns) was ca. 20% higher. The main result is that the strong damage to cotyledons (more than one fifth of acorn mass) caused a decrease of seedling height and mass even after the second growing season. Negative consequences on seedling root/shoot ratio or on their metabolism were not observed.

• Conclusion

We conclude that this method is useful for seedling production in containers when acorn mass is reduced by one fifth.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In recent years, the production of forest tree seedlings (including oaks) very often occurs in container nurseries. Production of seedlings in containers requires simultaneous germination and emergence, because if there are large differences in the time of germination, the earlier germinated plants quickly develop leaves which overshadow neighbor seedlings and restrict access to water (Suszka 2006). European oaks — pedunculate (Quercus robur L.) and sessile oak (Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) — germinate unevenly under natural conditions. The difference between first and last germinating acorns can be up to a few weeks (Suszka et al. 2000). A technique that helps cause faster and more uniform germination in germination tests is to remove pericarp from the distal end of the seed (ISTA 1999). A modified version of this method—to cut off about 1/3 of the distal ends of the acorns—is sometimes used in container nurseries (Suszka 2006). It is obvious that cutting off the distal ends of acorns damages and reduces the cotyledons. However, the process of damaging the pericarp and cotyledons without lethal consequences for seedlings sometimes occurs in natural conditions too, when mice bite off parts of acorns before seed germination (Andersson and Frost 1996). In the case of Quercus suber, cotyledon damage by insects causes faster and more synchronous germination of acorns (Branco et al. 2002). Oak germinates hypogeally; the acorns remain below the ground surface and do not take part in photosynthetic activity, remaining storage organs only. The consequences of cotyledon removal just after emergence of Quercus robur seedlings are very significant for seedling growth (Garcia-Cebrian et al. 2003). The growth, maturation and flowering of some dicotyledonous grassland species is also affected by cotyledon damage (Hanley and Fegan 2007). Kennedy et al. (2004) found that seed reserves have an important effect, especially for early performance of Lithocarpus densiflora seedlings. Total nitrogen content in the first Quercus mongolica leaves declined due to cotyledon damage caused by insects (Yi and Zhang 2008). However, Suszka et al. (2000), in their monograph on seeds of forest broadleaf species, state that removal of pericarp does not alter germination, emergence and development of seedlings. Valbuena and Tarrega (1998), also showed a lack of negative influence of mechanical scarification on germination of Quercus pyrenaica acorns. Therefore, the effects of cotyledon reduction on metabolic changes and development of seedlings are still not known (Giertych and Suszka 2010).

The aim of this study was to determine the influence of cutting away an increasing part of the distal (cap scar) end of acorns on development metabolism of pedunculate oak seedlings. We hypothesized that a small reduction of cotyledon size will be favorable for seedlings because the reduction of cotyledon reserves will be compensated by speeding up emergence and prolonging the first growing season. Greater reduction of the acorn mass should cause a significant decrease in seedling height.

We assumed that the restriction of growth will be greater for shoots of seedlings than for roots (i.e., enhanced root/shoot ratio), because the earlier developing root uses the majority of cotyledon reserves. The increasing of root/shoot ratio may decrease carbon assimilation due to decreasing area of leaf surface (Yi and Zhang 2008). We also hypothesized that the consequences of reducing cotyledons will not depend on acorn size. Acorn reduction decreases the amount of cotyledon reserves and may change seedling metabolism, especially nitrogen uptake (Villar-Salvador et al. 2010). We hypothesized that this procedure, by restriction of storage reserves within the cotyledons, causes changes in metabolism of young seedlings, and decreases the leaf and root content of carbohydrates and costly defense metabolites such as phenolic compounds.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Plant material

Acorns of three Polish provenances of Quercus robur (Krotoszyn 51°39’N; 17°27’E, Roszków 51°57’N; 17°26’E, Oborniki Śląskie 51°17’N; 16°54’E) were obtained from the forest storehouse in Jarocin, Poland. Mature acorns were collected in autumn 2003; they were subjected to a standard procedure of thermotherapy and fungicide — Dithane M-45, 1.5g/kg (Suszka et al. 2000). After 7 months storage (at −3°C), they were sown horizontally at 2–3cm depth (24.05.2004) individually in 2-liter pots filled with a 1:1 ratio (v/v) mixture of forest soil and peat with the addition of Osmocote® fertilizer, with a controlled release over a period of 5–6 months. Before sowing acorns were randomly assigned to five experimental treatments: 1 — untreated control, 2 — cutting off the scar of the pericarp and seed coat (DC), 3 — cutting off 1/5 of the distal end of acorns , 4 — cutting off 1/2 of the distal end of acorns , 5 — cutting off 2/3 of the distal end of acorns. Each of the five treatments had 108 acorns except the control, which had 132 acorns. The number of control acorns was greater because during preparation of other treatments we threw away all damaged acorns, and we wanted to get a similar number of seedlings for the biometrical and chemical analyses. Each acorn was weighed before and after preparation to control the mass of reduction. Two blocks were established, and pots were placed under the cover of polypropylene shade cloth, 2 m above the floor, with 50% light transmittance. The final experimental design had 18 (22 for control) acorns (replicates) for each block, provenance and experimental treatment. The seedlings were watered as necessary. During winter, the pots were covered with sawdust to protect the roots from freezing damage. The experiment was carried out in the experimental field of the Institute of Dendrology in Kórnik, Poland (52°14’N; 17°06’E; 75 m altitude).

2.2 Growth parameters, morphological and chemical analyses

Every week, seedling emergence was noted, and the height of all seedlings was measured through the end of the first growing season. The measurements of height started 6 weeks after sowing, when almost all seedlings had emerged. In August and October of the first growing season and October of the second growing season, 60 seedlings (four from each provenance and preparation treatment) were randomly chosen for morphological and chemical analyses. After rinsing the roots, each seedling was divided into: main root, fine roots (<2 mm), stem, and leaves. All parts of seedlings were oven-dried (65°C for 48 h), powdered in a Mikro-Feinmühle Culattimill (IKA Labortechnik Staufen, Germany) and stored in plastic boxes. Nitrogen (N) and carbon (C) concentration in the leaves and roots were measured using the Elemental Combustion System CHNS-O (Constech Analytical Technologies Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). The concentration of phenolic compounds (TPh) was measured colorimetrically using Folin and Ciocalteu’s Phenol Reagent (SIGMA F-9252), following Johnson and Schaal (1957) as modified by Singleton and Rossi (1965). The content of total phenols was expressed in μmol of chlorogenic acid g-1 dry mass. Total soluble carbohydrates and starch concentrations were determined by a modification of the method described by Hansen and Møller (1975) and Haissig and Dickson (1979). Sugars were extracted from the tissue powder in methanol–chloroform–water, and tissue residuals were used for starch content determination.

2.3 Statistical analyses

We used χ2 tests to recognize differences in emergence between experimental treatments. Seedling emergence data were examined by fitting temporal data for each treatment with the Richards' function (Richards 1959) using JMP statistical software (JMP version 7.0.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The Richards function was proposed for analyses of cumulative germination (Vannella 2003), and it can also be used for analyses of seedling emergence. The time trends derived from Richards function fittings are often more biologically meaningful than those of polynomial exponentials, and are recommended for use in plant growth analysis (Venus and Causton 1979). The form of the function was:

where Y is the total % of seedling emergence, a the asymptotic value for the function, b, c and d the shape parameters for the function, and x the number of days after sowing when the last measurement was made.

Mean absolute emergence rate (G; % day-1) over the whole period was calculated using parameters derived from a fitted Richards function. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the influence of provenance and preparation treatment on seedling height, leaf, shoot and root mass, leaf and root TPh, carbohydrates, N and C concentration. We did not observe any (except leaf nitrogen at the end of the first growing season) significant influence of provenance on the studied parameters, and we did not describe these results (see Appendices 1 and 2). The results expressed as percentages were arcsin transformed for analyses by ANOVA. The post hoc Tukey test was used to assess the differences among treatments. Normality of the distribution was tested using Shapiro–Wilk statistics. Linear regression analyses were done to estimate the consequence acorn size on seedling height for all experimental treatments. All analyses were conducted with JMP software (version 7.0.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Seedling emergence and growth dynamics

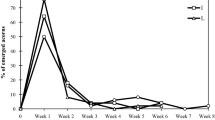

The reduction of acorn cotyledons caused faster and more uniform seedling emergence (Fig. 1). The damaged acorns (DC; 1/5; 1/2; 2/3 treatments) emerged significantly (χ2=22.0; p < 0.002) better (83–88%) than the controls (68%). The first seedlings from acorns with cut cotyledons (1/5; 1/2; 2/3 treatments) emerged 2 weeks after sowing. The majority of seedlings emerged nearly simultaneously, during 2 weeks between 17 and 30 days after sowing (Fig. 2). After 7 weeks, almost 80% emergence was observed. The first seedlings from DC and the control treatment also started emergence 2 weeks after sowing; however, the emergence rate of the majority of seedlings was longer and lasted 17 and 21 days for DC and control treatments, respectively. After 2 months, 50% of control seedlings emerged, and the last seedlings started emergence even after 10 weeks (Fig. 1).

Richards growth function for cumulative emergence (%) of pedunculate oak seedlings. The mean is shown for all provenances combined for each of the five experimental treatments (1 – untreated control, 2 – cutting off the scar of the pericarp and seed testa (DC), 3 – cutting off of 1/5 of the distal end of acorns, 4 – cutting off 1/2 of the distal end of acorns, 5 – cutting off 2/3 of the distal end of acorns)

Seedlings from all treatments ceased to grow at almost the same time (end of August), between the 240th and 248th day of the year, ca. 100 days after sowing (Fig. 3). In spite of the shorter duration of their growing season, the seedlings from DC and control treatments achieved a greater height (Figs. 3 and 4). The seedlings were significantly lower when the reduction of the acorn mass was 1/2 or 2/3.

Influence of experimental treatments on mean pedunculate oak seedling height (cm) at the end of the first growing season (See first figure for explanations). Means with the same letter are not significantly different (p < 0.05 ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test). Means shown in figures are average of all provenances. The vertical lines represent ±1 standard error of the mean

The cutting of acorns also alters the mass of seedlings and their parts. The effects of acorn reduction were evident at the end of the second growing season (Fig. 5). Significantly lower dry leaf mass of seedlings from the 1/2 and 2/3 treatments was found only when they were harvested at the end of August of the first year (Fig.5b). In the cases of shoot and root mass, significant consequences of acorn reduction were evident at the end of the second growing season (Fig. 5c,d). The influence of this procedure on the shoots and the roots of seedlings was similar and we did not find changes in the root/shoot mass ratio.

Influence of experimental treatments on mean pedunculate oak seedling (a), shoot (b), leaf (c) and root (d) dry mass (g), twice in the first and at the end of the second growing season. Means with the same letter are not significantly different between treatment at the same time (p < 0.05 ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test). Means shown in figures are average of all provenances. The vertical lines represent ±1 standard error of the mean. (See first figure for explanations)

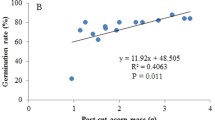

The seedling height at the end of the first growing season significantly depended on the size of acorns (Fig. 6); however, for higher levels of damage (1/2; 2/3 treatments) we did not observe this relationship.

3.2 Chemical composition

The influence of acorn reduction on nitrogen and carbon levels in the leaves and roots was not significant. The mean content of nitrogen and carbon stayed within the normal range for oak seedlings — leaf N 2.48(0.46); root N 2.06(0.41); leaf C 47.27(1.84); 45.3(3.53) — (all data for elements and carbohydrates are given in percentage of dry weight with SD in parenthesis). Among experimental variables only the date of harvest had a significant influence on the level of leaf nitrogen (lower at the end of the growing season) and root nitrogen and carbon (higher at the end of growing season).

Cotyledon reduction did not alter levels of carbohydrate and phenolic compounds in oak seedlings. Content of soluble carbohydrates in the leaves 6.3(1.8) and roots 4.7(1.9) was typical for oak seedlings and significantly increased at the end of the first growing season. Starch content in the roots was higher 3.6 (4.4) than in the leaves 0.6(0.3) but we did not observe differences among the sampling dates. The level of phenolic compounds in leaves and roots was very similar, 243.6(57) μmol d.wt and 247.8(64.2) μmol respectively. At the end of the growing season, we noted a significant 20% increase of phenolic compounds only in the roots.

4 Discussion

4.1 Biological aspects

As we expected, seedlings from the damaged acorns emerged earlier than those from controls. A similar reaction from simulated seed predation was described by Vallejo-Marin et al. (2006) for some neotropical rain forest tree species. Suszka (2006) also mentioned that similar effects were caused by cutting off about 1/3 of the distal ends of acorns. This meets the expectations of seedling producers, especially when the seedlings are cultivated in container nurseries. In the literature there is still a lack of information about consequences of this procedure for seedling development, because the previous studies on simulated seed damage dealt mainly with seed germination or emergence rate. The reason for faster germination of damaged acorns is unknown. According to (Finch-Savage and Clay 1994), mature acorns require a supply of external water to split the pericarp and begin radicle extension, so this procedure probably allows faster penetration of water into the seed. A second explanation for faster germination of damaged acorns is increased levels of plant growth regulators connected with germination, particularly IAA — indoleacetic acid (Finch-Savage and Farrant 1997; Prewein et al. 2006). The increase of IAA in cotyledons may be connected with better water supply; a similar phenomenon has been observed in coffee flower buds soon after plants were released from water stress (Schuch et al. 1994).

The procedure (removing part of the tips of acorns) studied here takes advantage of the natural ability of oak seeds to tolerate small levels of damage. Oaks are zoochoric species and acorns are dispersed and very often partially damaged by rodents, squirrels and birds. The jay (Garrulus glandarius L.) hoards and hides acorns in the ground in the autumn, and in the spring it locates young seedlings and removes and eats cotyledons (Ouden et al. 2005; Sonesson 1994). The removal of cotyledons 3 weeks after emergence did not influence the mass and height of Quercus robur seedlings (Andersson and Frost 1996). However, significant consequences of cotyledon removal on seedling mass were observed when the cotyledons were removed during the first 2 weeks after emergence (Garcia-Cebrian et al. 2003). Our results show that the degree of acorn damage is very important. Cutting off 1/5 of the distal end of acorns caused over 10% reduction of seedling height after the first growing season, and reduction of height after the second year was not significant. However, higher damage (1/2 or 2/3 acorn mass) caused significant reductions in first and second year heights, 32% and 45% respectively.

The reduction of seedling heights after insect damage of Quercus suber acorns was noted also by Branco et al. (2002). However, in the case of the large-seeded tropical species Gaustavia superba, tolerance of partial (even 50%) damage caused by simulating insect attacks has been shown (Dalling and Harms 1999). Results of our experiment and literature data suggest that the amount of reserve substances in oak cotyledons is greater than the needs of young seedlings if they grow under optimal conditions. This extra investment of parental resources in the progeny is due to better seed dispersion. According to Gomez et al (2008) heavier acorns were dispersed further, and were more likely to be cached and survive than lighter acorns. The loss of small parts of cotyledons, or their removal a few weeks after germination, does not have negative consequences for seedling development.

In oaks, the roots start to develop first and the epicotyls 20 days later (Suszka et al. 2000). We hypothesized that at the end of the growing season the shoots of seedlings will be more restricted than roots when a larger part of the cotyledons is damaged, because the root will use up the majority of reserve substances from the cotyledons. However, the root/shoot mass ratio did not differ among the treatments. Removal of cotyledons 1 week after emergence also did not influence these proportions (Sonesson 1994); this means that cutting of a small part or removal of cotyledons at that time does not influence shoot development more, as we had assumed.

In many tree species, initial seedling growth is positively correlated with seed mass (Howe and Richter 1982; Vaughton and Ramsey 1998; Sousa et al. 2003; Kennedy et al. 2004), and this is also true in oak species (Merouani et al. 2001; Grossman et al. 2003). Furthermore, larger oak acorns have a higher germination rate (Gomez 2004; Tilki 2010). In our experiment the second relationship did not exist, and the first was significant only for controls and slightly damaged acorns. Bigger seedlings grew from heavier acorns. However, the height of seedlings from strongly damaged acorns (1/2; 2/3 treatments) did not depend on the initial acorn mass (Fig. 6). We do not know why the growth reduction of young seedlings caused by cutting off the distal ends of acorns is greater for bigger acorns. This may be connected with the unequal distribution of metabolites in the cotyledons. Steele et al. (1993) concluded that the content of tannins differed significantly between basal and distal parts of acorns, and it was higher near the embryo axis to protect it from predators (rodents or birds) and insects. It is also probable that storage metabolites in oak cotyledons are unequally distributed, although we had no evidence that heavier acorns have more reserves in the distal portion. Other explanations for this result may be connected with the surface area of the cut, which was greater in bigger acorns. This could cause more desiccation of sensitive cotyledons, and could change the water potential gradient driving water flow to the axis from the cotyledons (Finch-Savage and Clay 1994). These results did not confirm our initial hypothesis that consequences of reducing acorns do not depend on their size.

Reduction of storage substances (Bonfil 1998; Garcia-Cebrian et al. 2003) and nutrients (Milberg and Lamont 1997) in cotyledons can alter the survival and development of seedlings. Kennedy et al. (2004) demonstrated that the amount of seed reserves, as well as the removal of cotyledons, significantly influenced photosynthesis and carbon management in very young Lithocarpus densiflora seedlings. There is a lack of information in the literature on oak seedling physiology and metabolism after cotyledons are damaged. Our results showed that after cutting the distal end of cotyledons, the level of carbohydrates, total soluble phenolic compounds, and the content of the main elements carbon and nitrogen in leaves or roots of the young seedlings, were not affected at the end of the growing season. Carbon supplies from cotyledons and other carbohydrate reserves in some tropical tree species enhanced the ability of seedlings to cope with herbivores and disease (Kitajima 2003). The lack of significant changes we observed in levels of the main metabolites is very advantageous for seedling producers, because the seedlings from damaged acorns would have an ability to defend themselves against herbivores and diseases similar to that of the controls. Changes in the content of nitrogen, carbon, and phenolic compounds in leaves and roots observed during growth were connected with physiological senescence.

4.2 Implications for nursery practices

The method of acorn damage before sowing has both advantages and disadvantages. Significant acceleration and simultaneous emergence of seedlings are advantages. In the case of container production of oak seedlings, this allows use of the same space in the greenhouses more than once during one season. The next advantage is the ca. 20% better seedling emergence caused by rejecting spoiled acorns when the distal ends are cut off. The seedlings obtained have appropriate proportions between the roots and shoots, but they are somewhat shorter, and in the case of large reductions (2/3 of acorn mass) as much as 45% shorter. The disadvantage of this method is that the acorn reduction must be performed manually. On the basis of our results we can say that only a small reduction of acorns (max. 1/5 acorn mass) would be optimal for seedling producers.

References

Andersson C, Frost I (1996) Growth of Quercus robur seedlings after experimental grazing and cotyledon removal. Acta Bot Neerl 45:85–94

Bonfil C (1998) The effects of seed size, cotyledon reserves, and herbivory on seedling survival and growth in Quercus rugosa and Q. laurina (Fagaceae). Am J Bot 85:79–87

Branco M, Branco C, Merouani H, Almeida MH (2002) Germination success, survival and seedling vigour of Quercus suber acorns in relation to insect damage. For Ecol Manage 166:159–164

Dalling JW, Harms KE (1999) Damage tolerance and cotyledonary resource use in the tropical tree Gustavia superba. Oikos 85:257–264

Finch-Savage WE, Clay HA (1994) Water relations of germination in the recalcitrant seeds of Quercus robur L. Seed Sci Res 4:315–322

Finch-Savage WE, Farrant JM (1997) The development of desiccation-sensitive seeds in Quercus robur L: Reserve accumulation and plant growth regulators. Seed Sci Res 7:5–39

Garcia-Cebrian F, Esteso-Martinez J, Gil-Pelegrin E (2003) Influence of cotyledon removal on early seedling growth in Quercus robur L. Ann For Sci 60:69–73

Giertych MJ, Suszka J (2010) Influence of cutting off distal ends of Quercus robur acorns on seedling growth and their infection by the fungus Erysiphe alphitoides in different light conditions. Dendrobiology 64:73–77

Gomez JM (2004) Bigger is not always better: Conflicting selective pressures on seed size in Quercus ilex. Evolution 58:71–80

Gomez JM, Puerta-Pinero C, Schupp EW (2008) Effectiveness of rodents as local seed dispersers of Holm oaks. Oecologia 155:529–537

Grossman BC, Gold MA, Dey DC (2003) Restoration of hard mast species for wildlife in Missouri using precocious flowering oak in the Missouri River floodplain, USA. Agroforest Syst 59:3–10

Haissig BE, Dickson RE (1979) Starch measurement in plant tissue using enzymatic hydrolysis. Physiol Plant 47:151–157

Hansen J, Møller I (1975) Percolation of starch and soluble carbohydrates from plant tissue for quantitative determination with anthrone. Anal Biochem 68:87–94

Hanley ME, Fegan EL (2007) Timing of cotyledon damage affects growth and flowering in mature plants. Plant Cell Environ 30:812–819

Howe F, Richter WM (1982) Effects of seed size on seedling size in Virola surinamensis; a within and between tree analysis. Oecologia 53:347–351

ISTA (1999) Proceedings of the International Seed Testing Association. International rules for seed testing. Seed Sci Technol 27:1–333

Johnson G, Schaal LA (1957) Accumulation of phenolic substances and ascorbic acids in potato tuber tissue upon injury and their possible role in disease and resistance. Am Potato J 34:200–202

Kennedy PG, Hausmann NJ, Wenk EH, Dawson TE (2004) The importance of seed reserves for seedling performance: an integrated approach using morphological, physiological, and stable isotope techniques. Oecologia 141:547–554

Kitajima K (2003) Impact of cotyledon and leaf removal on seedling survival in three tree species with contrasting cotyledon functions. Biotropica 35:429–434

Merouani H, Branco C, Almeida MH, Pereira JS (2001) Effects of acorn storage duration and parental tree on emergence and physiological status of cork oak (Quercus suber L.) seedlings. Ann For Sci 58:543–554

Milberg P, Lamont BB (1997) Seed/cotyledon size and nutrient content play a major role in early performance of species on nutrient-poor soils. New Phytol 137:665–672

Ouden J den, Jansen PA, Smit R (2005) Jays, mice and oaks. Predation and dispersal of Quercus robur and Q. petraea in north-western Europe. In: Forget PM, Lambert JE, Hulme PE, Vander Wall SB (eds) Seed fate: predation, dispersal and seedling establishment. CAB International, Wallingford, pp 223–239

Prewein C, Endemann M, Reinohl V, Salaj J, Sunderlikova V, Wilhelm E (2006) Physiological and morphological characteristics during development of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) zygotic embryos. Trees 20:53–60

Richards FJ (1959) A flexible growth function for empirical use. J Exp Bot 10:290–300

Schuch UK, Azarenko AN, Fuchigami LH (1994) Endogenous IAA levels and development of coffee flower buds from dormancy to anthesis. Plant Growth Regul 15:33–41

Singleton VI, Rossi JA (1965) Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagent. Am J Enol Viticult 16:144–158

Sonesson LK (1994) Growth and survival after cotyledon removal in Quercus robur seedlings, grown in different natural soil types. Oikos 69:65–70

Sousa WP, Kennedy PG, Mitchell BJ (2003) Propagule size and predispersal damage by insects affect establishment and early growth of mangrove seedlings. Oecologia 135:564–575

Steele MA, Knowles T, Bridle K, Simms EL (1993) Tannins and partial consumption of acorns — implications for dispersal of oaks by seed predators. Am Midl Nat 130:229–238

Suszka B (2006) Generative propagation. In: Bugała W. (Ed.) Dęby (Quercus robur L.; Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) — Nasze drzewa leśne. Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Poznań, pp 305–388

Suszka B, Muller C, Bonnet-Masimbert M (2000) Nasiona Drzew Leśnych. Od zbioru do siewu. PWN, Warszawa-Poznań, 307 p

Tilki F (2010) Influence of acorn size and storage duration on moisture content, germination and survival of Quercus petraea (Mattuschka). J Environ Biol 31:325–328

Valbuena L, Tarrega R (1998) The influence of heat and mechanical scarification on the germination capacity of Quercus pyrenaica seeds. New For 16:177–183

Vallejo-Marin M, Dominguez CA, Dirzo R (2006) Simulated seed predation reveals a variety of germination responses of neotropical rain forest species. Am J Bot 93:369–376

Vannella S (2003) Mathematical function applied in the cumulative germination studies. Seed Sci Technol 31:231–248

Vaughton G, Ramsey M (1998) Sources and consequences of seed mass variation in Banksia marginata (Proteaceae). J Ecol 86:563–573

Venus JC, Causton DR (1979) Plant growth analysis: a re-examination of the methods of calculation of relative growth and net assimilation rates without using fitted functions. Ann Bot 43:633–638

Villar-Salvador P, Heredia N, Millard P (2010) Remobilization of acorn nitrogen for seedling growth in holm oak (Quercus ilex), cultivated with contrasting nutrient availability. Tree Physiol 30:257–263

Yi XF, Zhang ZB (2008) Influence of insect-infested cotyledons on early seedling growth of Mongolian oak, Quercus mongolica. Photosynthetica 46:139–142

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Ms. Alicja Bukowska, Ms. Ewa Mąderek and Ms. Anna Nowak for their help with the chemical analysis. We are grateful to Dr. Lee Frelich from University of Minnesota for correcting language in the final version of the manuscript, and thank three anonymous reviewers for useful comments and suggestions. This study was supported by Institute of Dendrology Polish Academy of Sciences.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling Editor: Gilbert Aussenac

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Giertych, M.J., Suszka, J. Consequences of cutting off distal ends of cotyledons of Quercus robur acorns before sowing. Annals of Forest Science 68, 433–442 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-011-0038-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-011-0038-6