Abstract

The importance of a hired workforce for the competitiveness of livestock farms emerges in a context of a decreasing family workforce and increasing farm size. Farmers’ need for a regular workforce to perform labor-intensive tasks can conflict with the attractiveness of jobs and high rates of turnover among farm employees. Within farmers’ strategies to attract and retain employees, little attention has been given to understand the role of work changes over time during the careers of employees on farms. We thus developed a framework to understand how employees’ work organization on farms change over time since recruitment. Key concepts from human resource management and organizational change are the theoretical guidelines used to shape the framework. This conceptual base indicates what needs to be considered to understand changes in employees’ work. Empirical data were used to transform the concepts into practical variables to analyze changes in employees’ work. We interviewed 14 employees and 8 farmers (their employers) on dairy farms and collected data on work organization and changes over time, focusing on tasks performed by employees since recruitment, team composition, and farm history. The framework is composed of 8 variables that describe how work evolves according to changes in task assignments, changes in the way work is organized (versatility vs. specialization), and the level of autonomy afforded to workers. It also considers what drives these evolutions and the rhythm of evolution over time. The framework can be used by researchers to better understand trade-offs between labor management and farm changes over time. This is a new approach for analyzing work organization on livestock farms considering changes in work from the perspective of employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Employees represent 40% of the agricultural workforce worldwide (International Labour Office 2007). A hired workforce is a critical factor for farm competitiveness in developed countries, where family workforces are declining and farms are becoming larger. This is a particular challenge for dairy farms, affected by low career attractiveness among employees and high rates of turnover (Nettle 2018). Milk is the only agricultural product in the world produced daily, which requires a permanent workforce to perform regular labor-intensive tasks (Douphrate et al. 2013).

These issues have increased the interest among agricultural scientists and advisors in human resource management on farms (Brasier et al. 2006; Hyde et al. 2011). Empirical studies have highlighted a diverse range of strategies to attract and retain employees, including attractive wages and monetary incentives based on employees’ performance (Przewozny et al. 2016), social benefits and safer working conditions (Dumont and Baret 2017), and psychosocially appropriate working environments (Kolstrup et al. 2008). However, these studies have focused on farmers’ practices for managing human resources (Bitsch et al. 2006) and the effect of these practices on farm performance (Hyde et al. 2008) rather than on employees and their motivations for leaving or staying on farms. Moreover, specialized literature in human resource management has indicated that incentives and benefits are not enough to avoid turnover when career perspectives are not considered as well (Wesarat et al. 2014). Performing repetitive tasks and staying in the same job position for a long time decreases job satisfaction, which is related to turnover (Foong-Ming 2008).

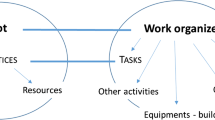

Researchers of work organization (defined by who does what and when) on livestock farms have indicated that changes in the work are related to the farm workers and the farm (Madelrieux and Dedieu 2008). Improving employees’ technical skills and knowledge through education and training is an important way to enable them to perform different tasks and advance in their job positions (Hutt and Hutt 1993). Individual technical skills and knowledge can change to match the needs of the skilled workforce on dairy farms (Bitsch and Olynk 2007; Mugera 2012) when adopting new technologies and practices (Cofre-Bravo et al. 2018). Nevertheless, less attention has been paid to how employees’ work changes on the farm over time, such as the tasks performed, the schedule of work (flexibility), and the freedom to take initiatives (Fig. 1). These factors have implications on employees’ job satisfaction and their intention to stay working in the farm (Nettle 2012).

The aim of the study was to develop a framework to understand how employees’ work organization on farm change since recruitment. It is necessary to develop approaches that better consider trade-offs between labor management and farm management over time and to provide insights into long-term retention of employees by developing their careers on farms.

In the following section, we present how empirical data were obtained from individual interviews with employees and their employers on dairy farms and then present the key concepts structuring the construction of our framework. In the final section, we present the results by describing the framework’s identification of different evolutions of employees’ work and its application to dairy farms.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Why choose non-familiar permanent employees on dairy farms in France?

We considered that the role of hired workers is more clearly defined than those of family members working on a farm. An employee who does not belong to the farmer’s family may have clear tasks to perform, clear instructions about how to perform the tasks and defined boundaries with regard to taking initiatives.

According to French agricultural statistics, demand for non-familiar permanent employees on dairy farms has increased by 2.3% per year since 2000, while demand on pig farms has increased to a lesser extent (0.9% per year), and decreased on beef cattle farms (0.8% per year) (Agreste 2014). We defined “permanent employees” as those who have regularly worked on the same farm for at least 1 year.

Permanent employees provide a workforce to perform regular labor-intensive tasks, especially milking on large dairy farms (Mugera 2012). However, dairy farms have a diverse range of tasks that can be performed by permanent employees, linked to the herd (e.g., feeding, calving, veterinary care), grasslands and crops (e.g., haymaking, silage, crop harvesting), or processing (e.g., cheesemaking).

2.2 Sampling criteria and data collection

Our aim was to identify generic variables to take into account the diversity of changes in employees’ work over time to build the framework. We sought to consider the broadest range of situations possible in terms of employees’ work and characteristics of the dairy farms. The five sampling criteria were as follows: (1) how frequently the employee works on the dairy farm (e.g., full-time, part-time, twice a week); (2) length of time the employee has worked on the dairy farm: from 1 year as the minimum amount of time to 15 years at the year of the interview as the maximum; (3) composition of the team working on the farm; (4) specialized dairy farms or diversified farms with milk production; and (5) geographic area (mountainous area or lowland).

Semi-directed interviews were conducted with eight farmers and their 14 employees. Farmers were interviewed in November 2014 about changes in employees’ activities since they were recruited. Three main topics discussed were (1) farm history: description of the structure and changes over time (e.g., size, herd size, technical practices) and changes in the composition of the team working on the farm over time; (2) employee recruitment: reasons for recruitment and job description; and (3) work organization: description of tasks performed by employees and changes (what, when, with whom and how).

Employees were interviewed in November 2015 about changes in their activities on the farm and the links between these changes and their working conditions. The main topics discussed were (1) changes in tasks performed, (2) reasons for these changes, (3) the consequences on their working conditions (e.g., instructions for performing tasks, work schedule, working alone), and (4) reasons to be an employee and perspectives in their career.

2.3 Sample description

The sample was composed of 14 employees working on eight large dairy farms in Auvergne, central France. The nine men and five women ranged in age from 22 to 50 years old. Eleven employees had technical education in agriculture or animal production, while the other three had neither technical education nor professional experience in agriculture. Seven employees were full-time workers (40 h/week); three employees were shared workers in an employer group and worked twice a week per farm (15 h/week); and four employees were part-time workers (25 h/week). Five farmers hired one employee, while the other three hired respectively, two, three, and four employees. The eight dairy farms were larger than the average French dairy farm in terms of farm and herd size: 150 ha and 93 dairy cows compared to 95 ha and 49 dairy cows, respectively (Agreste Primeur 2013). Half of the farms were specialized in dairy production, while the other half were diversified (crop and/or cheese production).

2.4 Building the framework with concepts and empirical data

2.4.1 Conceptual guidelines from management science to understand changes in employees’ work

We bring together two fields on management science—human resource management and organizational change—to better understand changes in the employees’ work organization on livestock farms since recruitment. The literature in the first field, human resource management, provides three useful concepts about development of employees’ careers in the non-agricultural sector: assignment of tasks, versatility vs. specialization, and autonomy (Vafaï and Anvar 1998; Everaere 2006, 2008).

Assignment of tasks is a way to organize work by defining each task to be performed and the associated technical responsibilities (Vafaï and Anvar 1998). According to the way tasks are assigned, work organization on farms can be centralized or decentralized. Centralized work means that most tasks and responsibilities are concentrated on one person, while decentralized work means that tasks and responsibilities are shared between people (Hutt and Hutt 1993). Thus, changes in tasks and responsibilities assigned to employees on livestock farms tend to increase centralization or decentralization over time.

Versatility and specialization are different ways to organize work. Specialization is strongly related to Taylorism. Based on a scientific division of work (Taylor 1914), production activities are divided into several tasks, with each task performed by one worker. The concept was largely used in industrial organizations, in which workers repeatedly perform a single task following strict prescription (Everaere 2008). A similar situation was observed on large dairy farms, where certain workers are assigned exclusively to milking (Harrison and Getz 2015). Versatility is a post-Taylorism form of work organization that recommends flexibility in work (Peaucelle 2009). Workers thus perform different jobs with several tasks (Everaere 2008). For example, on small mountain dairy farms, workers perform a range of tasks, including milking, feeding, soil preparation, and haymaking (Dupré 2010). Changes in the tasks and responsibilities assigned to employees affect their job positions on farms, which leads their careers on the farm to specialization or versatility.

Autonomy is defined as the room that a worker has to maneuver to perform a task according to the prescription (Everaere 2006). Prescription is defined as instructions on how to perform the tasks (Leplat 2004). The performance of tasks following strict prescription with no or few technical responsibilities indicates a low level of autonomy (Everaere 2006). This is the case for industrial workers who have to follow standard procedures (Peaucelle 2009). Meanwhile, performing tasks with the possibility to take initiatives or adapt the prescription indicates a high level of autonomy (Everaere 2006). This is the case of managers in industry or service sectors, such as managers of large supermarkets (Sguerzi-Boespflug 2008). Changes in the prescriptions that employees have for performing tasks on farms may lead to more or less autonomy in their work.

Those concepts from the literature in human resource management are useful to address the lack of knowledge about work content, job positions, and technical responsibilities of employees on livestock farms. Finally, assignment of tasks, versatility vs. specialization, and autonomy are the three dimensions of work that describe evolutions in employees’ work. These evolutions are diverse when considering combinations of the centralization or decentralization of tasks and responsibilities, the demand for versatile or specialized employees, and the degree of precision of the prescriptions.

The literature in the second field, organizational change, indicates that any longitudinal change is composed of three dimensions—content, motors, and time—and interactions between them (Pettigrew 1990; Ven and Poole 1995; Huy 2001). The content of changes represents the main elements that make up a pathway (Pettigrew 1990). We understand that content allows us to describe evolutions in employees’ work over time, which is composed of the three dimensions of work from human resource management literature (assignment of tasks, versatility vs. specialization, and autonomy).

Motors are mechanisms that generate changes by acting on the contents of the pathways (Ven and Poole 1995). The action of motors explains why changes or stability occur throughout time in the three dimensions of employees’ work (Brochier et al. 2010). Changes are produced over time when actions of motors are combined, while stability is produced when actions of motors are contradictory (Ven and Poole 1995). Motors are embedded in the context of evolutions (Pettigrew 1990). There are two types of context. Outer context refers to the frame in which evolutions take place, while inner context refers to characteristics and features of the entity that is evolving (Pettigrew 1990). On this basis, we understand that evolutions in employees’ work are related to the livestock farm and the employees themselves. Time is an intrinsic aspect when analyzing changes, since changes are observed over time (Pettigrew 1990; Huy 2001; Bidart et al. 2012). Evolutions in work may have different timings, yielding alternation between periods of change and stability. In this article, the timing of evolutions in work is related to the frequency of changes and their distribution during the period analyzed. The aim is to qualify the concentration or distribution of changes over time and the stability between changes.

Finally, the conceptual structure of our framework is composed of the following: three dimensions indicating changes in employees’ work (assignment of tasks, specialization vs. versatility, and autonomy); drivers of these changes, which are linked to employees themselves and the livestock farm; and rhythms of changes in employees’ work since recruitment.

2.4.2 Identification of variables describing changes in employees’ work on livestock farms

The conceptual structure of our framework indicates what needs to be considered to understand changes in employees’ work on a farm since recruitment. However, it does not describe how changes occurred over time or how diverse those changes can be. Therefore, we needed to identify variables to describe how employees’ work changes since recruitment. Empirical data were used to identify variables that describe the diversity of changes in employees’ work.

Data were analyzed in three steps. First, the data from each interview were analyzed in detail to describe how employees’ work evolved over time and to identify factors driving the observed evolutions and the rhythm of these evolutions. The interviews were transcribed in their entirety and systematically coded using NVivo 10 software (Hutchison et al. 2010). Coding themes emerged from the literature review of human resource management and organizational change, and from our empirical data. In a second step, analyses were compiled in a monograph for each employee per farm. Each monograph described two main parts: changes in the three dimensions of work (task assignments, versatility vs. specialization, and autonomy) and factors driving the evolutions and the rhythm of these evolutions. In a third step, the monographs were compared to identify all variables that described and explained evolutions in employees’ work on farms (Girard et al. 2008). The two most different monographs were compared to identify variables that describe the evolution in the three dimensions of work, the motors, and the rhythm of evolutions. The categories were built progressively by considering other monographs until no additional category was identified.

3 Results and discussion

The framework allows the description and explanation of evolutions in employees’ work organization on livestock farms. The framework is composed of the following: 19 variables describing how work evolves according to the three dimensions of work analyzed (assignment of tasks, versatility vs. specialization, and autonomy); three groups of motors explaining work evolutions; and three types of rhythm of evolutions that describe how the evolutions take place over time. A graphic representation demonstrated the articulations between framework items (Fig. 2). All components of the framework are presented in the following sections.

Graphic representation of framework of work evolution at individual level: its items and types of relations. The synergies (arrows) between motors act on the variables of each dimension (circles). It makes the evolution of work. The evolutions are described by categories (e.g., text next to axes extremity associated to gradient colors in the circles). The ways of evolutions are indicated by arrows according to the different rhythms of evolutions: progressive (arrow), sudden (thick arrow), and stable (thin arrow)

3.1 Three dimensions of work evolution according to changes in tasks assigned, trends between versatility and specialization, and the level of autonomy

Our sample revealed high diversity among employees in evolutions in tasks assigned, trends between versatility and specialization, and levels of autonomy. The variables and categories describing this diversity are summarized below (Table 1).

3.1.1 Three variables describing evolutions in assignment of tasks

Three variables describe evolutions in tasks performed by employees since their recruitment on farms (Table 1). The first variable, “evolution in the number of tasks,” indicates evolution in the quantity number of tasks assigned to employees since recruitment, with two categories (Table 1) characterizing an increase or stability in the number of tasks performed. In our sample, most employees had additional tasks to perform, such as employees 12 and 13. They were hired to perform milking (cows and goats), but they started to perform additional tasks such as feeding, monitoring animals, and veterinary care: “I milked cows [at recruitment and after a few months) I did everything that needed to be done for the goats, including feeding, medicines to give them, monitoring animals” (employee 13). Assigning more tasks over time is a common farmer behavior to improve work flexibility (Hutt and Hutt 1993); for employees, it is a way to learn new tasks by performing them (Madelrieux et al. 2009).

The second variable, “evolution in the frequency of task execution,” indicates changes in the regularity of tasks performed by employees since recruitment (Table 1). The first category describes changes due to a planned event (e.g., milking every day, haymaking every summer) or an unexpected event (e.g., feeding if the farmer is ill). The second category indicates a stable frequency of tasks performed since recruitment. For most employees, the new tasks assigned were integrated into their routine work (e.g., feeding or identification of cows in heat every day), while a few employees had new tasks assigned to make their routine work more flexible (e.g., milking if the farmer is ill). This is the case of employee 3, who started to perform milking to replace the farmer when he attended professional meetings: “I performed several tasks, except milking at the beginning. [But] if they ask me, if the farmer needs, I stay or I come [to perform milking], but that’s all. Otherwise, I couldn’t work until 8 pm... For me, that’s called giving a hand” (employee 3).

The routine work of permanent workers is clearly defined (tasks, hours, etc.) in order to better share the workload with other members in the work group. Meanwhile, flexible routine work is common for shared employees from an employer group due to the room to maneuver to adapt according to the needs of the moment (Madelrieux et al. 2009).

The third variable, “evolution in the nature of tasks,” indicates the evolution in the type of tasks performed by employees since their recruitment; it has two categories describing the evolution (Table 1). The first category is “increasing execution and responsibility tasks.” Execution tasks are operational tasks that make dairy farms run, such as milking, feeding, and cheesemaking. Responsibility tasks are technical tasks that adjust, regulate, and orient how a dairy farm runs, such as selecting breeding bulls and identifying cows in heat or animal diseases. The second category, “execution tasks since recruitment,” indicates no changes in the nature of the tasks. Most employees perform only execution tasks during their career on a farm, while farmers prefer to perform responsibility tasks to better control the farm’s technical performance. This is a common arrangement when employees want to work closely with the animals but do not want to have technical responsibilities (Madelrieux et al. 2009). In contrast, some farmers integrate employees in technical decision making, such as employee 5, who selected breeding bulls with the farmer and the veterinarian: “I give my opinion about each cow, its body condition, milk production. (…) The veterinarian suggests a breeding bull and we [employee and employer] tell him what faults we think the cow has and what needs to be improved” (employee 5).

3.1.2 Two variables describing evolutions in versatility and specialization

Two variables describe evolutions in the level of versatility or specialization (Table 1). The first variable, “evolution in the number of jobs,” shows the evolution in the number of jobs since recruitment of the employee. A job is defined as a group of tasks linked to a central object. For example, the group of tasks linked to the animal is milking, feeding, identification of cows in heat, monitoring cow health, and veterinary care. This group of tasks thus characterizes the job of herd manager. Two categories describe the evolutions. In the first category, “from one job to multiple jobs,” employees perform one job at recruitment and then additional jobs over time (e.g., an employee hired as a milker who later becomes a milker and an agricultural machine operator). In the second category, “stable,” employees perform the same job since recruitment. For example, employee 8 had always worked as a cheesemaker: “It’s worked like this for a long time, the cheesemaker doesn’t touch the cows (…) he’s [employee 8] never milked a cow in his life, it isn’t his job” (employer 6). Becoming a versatile worker is less common than remaining a specialized or versatile worker since recruitment. For some authors, this stability is related to farm characteristics, such as farm size and level of specialization. On specialized large farms, employees are more specialized, while on diversified farms, they are more versatile (Harrison and Getz 2015).

The second variable, “evolution of the job,” qualifies the changes in the employee’s job after recruitment, and has three categories describing these changes (Table 1). For the first category, “progressive,” the job gradually changes over time to strengthen it. For example, employee 4, an agricultural machine operator initially assigned to soil preparation and sowing, was later asked to harvest crops as well and, after some time, apply herbicides. For the second category, “sudden,” the job changes only once since recruitment. This change can involve a change in the type of job or diversification of jobs: for example, employee 2 was a milker who became a livestock technician (change in type of job), and employee 10 was a cheesemaker who became a cheesemaker and milker (diversification). For the third category, “stable,” there is no change in jobs. For example, employees 6 and 7 were herd managers who had performed the same tasks since recruitment: “We make sure not to overload [employees’] jobs. (…) We understand that they are here to work, but if we overload [them] the quality of the work may decrease” (employer 6). Major job changes are concentrated at a specific moment in most employees’ careers, especially from 1 to 3 years after recruitment. Building commitment between employer and employee is important during this period; to this end, employers test employees’ technical skills (Madelrieux et al. 2009).

3.1.3 Three variables describing evolutions in autonomy

Three variables describe evolutions in levels of autonomy (Table 1). The first variable, “evolution in the type of task instructions,” indicates the evolution in the instructions given to the employee about how to perform tasks. It is described by three categories. The first category, “room to manoeuver to perform most tasks since recruitment,” indicates that employees can choose how to perform tasks once farmers give them an objective to accomplish (e.g., to monitor animal health, the employee can choose when to do it and which signs to consider).

The second category, “strict instructions at recruitment but later room to manoeuver to perform responsibility tasks,” indicates that newly recruited employees have to follow technical instructions about how to perform tasks (e.g., for milking, and doing so every day at the same time), but that over time they can choose how to perform responsibility tasks (e.g., monitoring animal health). However, strict instructions remain in place for execution tasks. The third category, “strict instructions for most tasks since recruitment,” indicates that employees must always follow the technical instructions about how to perform tasks (e.g., making cheese and milking). It is common for farmers to give employees strict instructions about how to perform work when they are recruited, notably through practical demonstrations, as explained by employer 8: “I worked with each of the employees for 15 days, observing [them], showing what has to be done…to clean equipment, milk, clean the milking parlor.” For employees, depending on their career goals, executing a standardized procedure is not a negative working condition (Everaere 2006); for farmers, it is a way to maintain the quality of tasks performed, such as cleaning procedures during milking, to control milk quality in large dairy farms (Harrison and Getz 2015).

The second variable, “evolution in working in a pair with a farmer,” indicates changes in the presence of a family member working with the employee since recruitment, and is described by two categories (Table 1). For the first category, “especially at recruitment and later for some employee tasks,” farmers and employees work together almost all day long, then over time they often work separately (e.g., working together at recruitment to perform milking and feeding every day, and later working together for milking on the weekends). For the second category, “since recruitment for most employee tasks,” farmers and employees work together to perform several tasks, such as milking, cheesemaking, calf birthing, and veterinary care. For example, employee 4 frequently worked with one of the three farmers on tasks such as milking: “At milking time there must always be a supervisor: my wife, or me, or my daughter and then other people [employee 4 and apprentices]” (employer 4). Employees and farmers work in pairs at recruitment so that farmers can show how they currently work on the farm, indicate which tasks employees are to perform, and observe how the employees work. This practice is common, especially on family farms that hire an employee (Madelrieux et al. 2009). Over time, the frequency of work in pairs decreases according to the employees’ ability to perform tasks according to instructions. On large dairy farms with several employees, a herd manager is in charge to verify the tasks performed by milkers (Harrison and Getz 2015).

The third variable, “evolution in the frequency of controlling which tasks are performed,” indicates the variation in the regularity of farmers’ control of employees’ tasks, with three categories describing the variation (Table 1). In the first category, “from recurring to occasional,” tasks performed by employees are controlled almost every day immediately after recruitment, and then less frequently over time until it becomes irregular (e.g., daily verification of feeding decreases to one verification per week). In the second category, “from recurring to regular,” tasks performed by employees are controlled almost every day at recruitment, and then less frequently until it becomes regular (e.g., daily verification of cheesemaking decreases to verification 2 or 3 days per week). In the third category, “recurring since recruitment,” tasks continue to be verified almost every day (e.g., daily verification of milking). Decreasing the frequency of monitoring is more common than maintaining the same frequency. It is a sign of mutual commitment to work between employers and employees (Madelrieux et al. 2009) and increases opportunities for employees to take initiatives (Everaere 2006). For farmers, task verification is also a way to control the quality of products, as explained by employer 8 for cheesemaking: “I check twice a day (…) but it doesn’t mean that [the employee] has no skills. It’s me; I want a product to turn out exactly the way I want. I’m very demanding” (employer 6).

The variables and categories that describe evolutions in the assignment of tasks, the trends between versatility and specialization, and the level of autonomy allow one to highlight both quantitative aspects of work, such as the number and frequency of tasks or number of jobs, and qualitative aspects, such as the nature of tasks or type of instructions (Table 1). These kinds of work characteristics are not considered in analyses of work organization on livestock systems, which are focused mostly on combinations of tasks with different rhythms (routine and seasonal tasks) to be performed by different groups of workers (basic group or out of basic group) (Madelrieux and Dedieu 2008; Hostiou and Dedieu 2012).

The three dimensions of work related to the human resource management approach are an original perspective with which to analyze work at the individual level on livestock farms. Other approaches with the same level of analysis are focused on subjective dimensions of work (e.g., personal experiences, different rationalities, professional career perspectives) (Madelrieux et al. 2009; Fiorelli et al. 2010; Coquil et al. 2014). Our results show a new way of taking human resource management into account when analyzing farm work. Indeed, several studies assess impacts of human resource management (e.g., hiring, training, monitoring) on employees’ work performance (Hyde et al. 2008; Mugera 2012) or to qualify workforce strategies on farms according to the skills and experience of different members of the workforce (employees, farmers, and contractors) (Nettle et al. 2018a). With our approach, human resource management is used to analyze changes in employee work.

Compared to organizational approaches, which are based on the social and technical division of work (who does what) and rhythm of technical practices (e.g., daily tasks or seasonal tasks) (Hostiou and Dedieu 2012), our framework provides a new viewpoint about work on farms by integrating a temporal perspective of change and by considering the different natures of tasks, the diversity of tasks performed, and the room to maneuver to perform tasks.

3.2 Motors and rhythms of work evolutions

Motors were classified into three groups according to the reasons for the evolutions in employees’ work (Table 2). The “farm” group concerns changes in farm structure, such as increasing herd and farm size. Employer 4 explained that he had assigned more tasks to employee 4 after buying land to increase the size of crop fields: “We bought 105 ha, so we went from 160 ha to 265 ha. (…) Now, he [employee 4] sows wheat… he had never applied herbicide; now he applies it. He started by doing a little bit last year [2015] and seems to have done a lot more of it this year [2016]” (employer 4).

The “team” group concerns changes in the composition of the team and availability of its members to work, such as the arrival or departure of farm workers. Employer 8 explained how his parents’ retirement affected the work of employee 14 regarding the sale of cheese at the local market: “My mother has gone to the local market since the 80s (…). [Employee 14] went to the local market a few times, but eventually, as my mother stops doing it, [employee 14] will do it more frequently” (employer 8).

The “farm worker” group concerns changes related to the employees themselves, such as skills or demands. Employee 5 explained why she had asked to perform the online declaration of a calf birth: “I volunteered because [the farmer] didn’t have the time… and I don’t mind doing it; I type faster than him on the keyboard” (employee 5). The three groups of motors act differently according to the three dimensions of work (Table 2). Tasks assigned to employees evolve due to changes in the farm, team, and farm worker. This was the case for an employee working on a diversified dairy farm with three other employees. When she started working on the farm, she was responsible for milking, but after increase in the size of the herd and the retirement of family workers, she developed technical skills to perform additional tasks, such as monitoring herd health and identifying cows in heat.

The versatility or specialization of employees evolves due to changes in the farm and the team. This was the case for an employee who had worked on a diversified dairy farm with three family workers. He was recruited as a versatile worker to perform several tasks, such as milking and operating agricultural machines (e.g., soil preparation, sward and crop harvesting). After the arrival of a family farmer associated with an increase in herd and farm size, his versatility increased to perform more tasks (e.g., feeding, haymaking, manure spreading, herbicide application).

The autonomy of employees evolves due to changes in the team and the farm worker. This was the case for an employee on a specialized dairy farm with one farmer. She was recruited to perform milking. Due to a high workload and to develop her technical skills, the farmer and employee worked ever more separately, allowing her to perform more tasks (e.g., feeding, soil preparation, manure spreading).

Our results highlight that evolutions in work are not only strongly related to changes in livestock farms but are also linked to the workers themselves, especially their technical skills. The benefits of skill development are twofold. For workers, it is a way to develop their careers (Moffatt 2016). For farmers, investing in and retaining a skilled workforce represent a competitive advantage for their farms (Mugera 2012).

The workload is currently identified as a reason for assigning tasks (Hutt and Hutt 1993). Our results show that it is also a reason for increasing autonomy, since assigning tasks to share the workload decreases the frequency of working in pairs.

Considering motors from individual, collective, and farm levels together is a new way to explain work evolution on livestock farms. At present, changes in work are usually explained by individual reasons (Fiorelli et al. 2010; Coquil et al. 2014) or technical practices and equipment facilities (Madelrieux and Dedieu 2008; Cofre-Bravo et al. 2018).

Three types of rhythms of evolution in employees’ work were identified. The “progressive” rhythm indicates several changes in work distribution over time. For example, employee 4 had worked on a diversified dairy farm for 4 years. He was recruited as a versatile worker to perform feeding, soil preparation, haymaking, and crop harvest. Over time, his work changed twice. He started to milk cows with family members 1 year after recruitment and to sow crops 2 years after recruitment. The progressive rhythm describes minor changes that can produce major changes through accumulation (Pettigrew 1990), such as changes in feeding practices over time due to an increasing herd size (Aubron et al. 2016).

The “sudden” rhythm indicates one change over time or concentrated changes. For example, employee 14 had worked on a diversified dairy farm for 6 years. She was recruited as a cheesemaker and became a versatile worker 4 years after recruitment due to the retirement of farmers. Sudden rhythms describe major changes that modify paths deeply (Bidart et al. 2012), such as changes in routine work organization due to workforce availability (Madelrieux and Dedieu 2008).

The “stable” rhythm indicates an absence of change over time. For example, employee 8 had worked as a cheesemaker on a specialized dairy farm for 5 years. Stable rhythms describe the continuity or the inertia of a path (Pettigrew 1990). This stability is observed in dairy farms in mountainous areas with versatile permanent employees who perform several tasks over time (Dupré 2010).

3.3 Framework applications

The framework was tested on employees on dairy farms, and five pathways of evolution of work were identified: (1) continuing to perform daily tasks, (2) increasing versatility to perform all routine tasks, (3) becoming a versatile employee to occasionally replace the farmer, (4) becoming a highly skilled dairy farm technician, and (5) becoming a farmer (Malanski et al. 2017). Differences between pathways depend on stability or changes (progressive or sudden) in the three dimensions of work analyzed (e.g., assignment of tasks, versatility vs. specialization, autonomy), the increasing size of both herd and farm over time, the availability of workers to work, and the development of employees’ technical skills.

The five pathways showed that work changes to more operational tasks (pathways 1, 2, and 3) or technical responsibilities (pathways 4 and 5). None of the pathways indicates evolutions in work that include responsibilities for human resource management. This is, however, one of the roles of managers on large dairy farms in the USA (Bitsch and Olynk 2007).

Similarities were found on other types of farms. On pig farms in France, employees performing daily tasks (e.g., farm assistants) can replace farmers on weekends (pathway 3) (Hostiou et al. 2007), while on industrial farms in Denmark, specialized employees (e.g., piggery attendants) autonomously perform a variety of tasks (e.g., feeding, pig handling, treating diseases) (pathway 4) (Roguet et al. 2010).

In the advisory process, these pathways could help reduce turnover on livestock farms. Before recruitment, advisors and farmers could better define the profiles and roles of employees according to the needs of the farmer. After recruitment, advisors, farmers, and employees could regularly discuss better ways to develop the latest career. In Australia dairy sector, farmers have succeeded in retaining employees by offering opportunities for developing their career on the farm though job positions (from assistant farm hand to farm manager), flexible work organization, and training (Nettle 2012). Moreover, advisors integrate farm human resource management in their portfolio of skills in order to better support farmers (Nettle et al. 2018b).

4 Conclusion

We developed an original framework to analyze changes in employees’ work organization in livestock systems by integrating key concepts from human resource management and organizational change. The framework is composed of variables that describe how work evolves according to changes in task assignment, changes in the way work is organized (versatility vs. specialization), and the level of autonomy afforded to employees. It also considers what drives these evolutions and the rhythms of evolutions over time.

Our new work organization approach is based on qualitative and quantitative criteria, such as the nature of tasks, type of task instructions, number of jobs, and frequency of working in pairs. Since temporal dynamics are essential in our framework, all of the framework’s variables and categories indicate evolutions by noting what changes and what remains stable in the employees’ work.

This framework can be used by researchers to better understand trade-offs between labor management and changes in livestock farms. For example, to assess how technical changes impact the tasks and the workload of employees. Regarding advisory services, however, it is necessary to adapt the framework in a tool containing operational indicators rather than concepts and variables. This tool could be used by advisors, farmers, and employees to plan together the best career advancement on farm.

The current context of changes in livestock farms is affected by increasing demand for a hired workforce and a decreasing family workforce; thus, farmers must be able to decrease turnover and adapt their farm management to remain competitive. The impacts of these changes in employees’ careers on dairy farms can be better assessed using the criteria provided by our framework.

References

Agreste (2014) Le bilan annuel de l’emploi agricole selon l’orientation technico-économique de l’exploitation: Résultats 2012. http://agreste.agriculture.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/partie1cd225bspca.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2017

Agreste Primeur (2013) Des territoires laitiers contrastés. http://agreste.agriculture.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/primeur308.pdf. Accessed 07 Sept 2016

Aubron C, Noël L, Lasseur J (2016) Labor as a driver of changes in herd feeding patterns: evidence from a diachronic approach in Mediterranean France and lessons for agroecology. Ecol Econ 127:68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.02.013

Bidart C, Longo ME, Mendez A (2012) Time and process: an operational framework for processual analysis. Eur Sociol Rev 29:743–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs053

Bitsch V, Olynk NJ (2007) Skills required of managers in livestock production: evidence from focus group research. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 29:749–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2007.00385.x

Bitsch V, Kassa GA, Harsh SB, Mugera AW (2006) Human resource management risks: sources and control strategies based on dairy farmer focus groups. J Agric Appl Econ 38:l23–l36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1074070800022112

Brasier K, Hyde J, Stup RE, Holden LA (2006) Farm-level human resource management: an opportunity for extension. J Ext 44:33

Brochier D, Garnier J, Gilson A et al (2010) Propositions pour un cadre théorique unifié et une méthodologie d’analyse des trajectoires des projets dans les organisations. Manag Avenir 36:84–107. https://doi.org/10.3917/mav.036.0084

Cofre-Bravo G, Engler A, Klerkx L et al (2018) Considering the workforce as part of farmers’ innovative behaviour: a key factor in inclusive on-farm processes of technology and practice adoption. Exp Agric:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479718000315

Coquil X, Béguin P, Dedieu B (2014) Transition to self-sufficient mixed crop–dairy farming systems. Renew Agric Food Syst 29:195–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170513000458

Douphrate DI, Hagevoort GR, Nonnenmann MW et al (2013) The dairy industry: a brief description of production practices, trends, and farm characteristics around the world. J Agromedicine 18:187–197

Dumont AM, Baret PV (2017) Why working conditions are a key issue of sustainability in agriculture? A comparison between agroecological, organic and conventional vegetable systems. J Rural Stud 56:53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.07.007

Dupré L (2010) Spécificités du salariat permanent en élevage laitier de montagne: une première approche dans les Alpes du Nord. Cah Agric 19:366–370. https://doi.org/10.1684/agr.2010.0423

Everaere C (2006) Pour une échelle de mesure de l’autonomie dans le travail. Rev Int Sur Trav Société 4:105–123

Everaere C (2008) La polyvalence et ses contradictions. Rev Fr Gest Ind 27:89–104

Fiorelli C, Dedieu B, Porcher J (2010) Un cadre d’analyse des compromis adoptés par les éleveurs pour organiser leur travail. Cah Agric 19:383–390

Foong-Ming T (2008) Linking career development practices to turnover intention: the mediator of perceived organizational support. J Bus Public Aff 2:1–16

Girard N, Duru M, Hazard L, Magda D (2008) Categorising farming practices to design sustainable land-use management in mountain areas. Agron Sustain Dev 28:333–343. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro:2007046

Harrison JL, Getz C (2015) Farm size and job quality: mixed-methods studies of hired farm work in California and Wisconsin. Agric Hum Values 32:617–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9575-6

Hostiou N, Dedieu B (2012) A method for assessing work productivity and flexibility in livestock farms. Animal 6:852–862. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731111002084

Hostiou N, Dedieu B, Pailleux J (2007) Le salariat en élevage porcin et les régulations du travail. Journ Rech Porc En Fr 39:193

Hutchison AJ, Johnston LH, Breckon JD (2010) Using QSR-NVivo to facilitate the development of a grounded theory project: an account of a worked example. Int J Soc Res Methodol 13:283–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570902996301

Hutt MJ, Hutt GK (1993) Organizing the human resource: a review of centralization, decentralization and delegation in agricultural business management. J Dairy Sci 76:2069–2079

Huy QN (2001) Time, temporal capability, and planned change. Acad Manag Rev 26:601–623. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2001.5393897

Hyde J, Stup R, Holden L (2008) The effect of human resource management practices on farm profitability: an initial assessment. Econ Bull 17:1–10

Hyde J, Cornelisse SA, Holden LA (2011) Human resource management on dairy farms: does investing in people matter? Econ Bull 31:208–217

International Labour Office (2007) Agricultural workers and their contribution to sustainable agriculture and rural development. ILO-FAO, Geneva

Kolstrup C, Lundqvist P, Pinzke S (2008) Psychosocial work environment among employed Swedish dairy and pig farmworkers. J Agromedicine 13:23–36

Leplat J (2004) Éléments pour l’étude des documents prescripteurs. Activités. https://doi.org/10.4000/activites.1293

Madelrieux S, Dedieu B (2008) Qualification and assessment of work organisation in livestock farms. Animal. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175173110700122X

Madelrieux S, Dupré L, Rémy J (2009) Itinéraires croisés et relations entre éleveurs et salariés dans les Alpes du Nord. Écon Ru 313–314:6–21. https://doi.org/10.4000/economierurale.2367

Malanski PD, Hostiou N, Ingrand S (2017) Evolution pathways of employees’ work on dairy farms according to task content, specialization, and autonomy. Cah Agric. https://doi.org/10.1051/cagri/2017052

Moffatt J (2016) Understanding career pathways in agriculture: theorising the farmhand career. Aust J Career Dev 25:129–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416216676605

Mugera AW (2012) Sustained competitive advantage in agribusiness: applying the resource-based theory to human resources. Int Food Agribus Manag Rev 15:27–48

Nettle R (2012) Farmers growing farmers: the role of employment practices in reproducing dairy farming in Australia. In: 10th IFSA symposium. Aarhus, Denmark, 11p

Nettle R (2018) International trends in farm labour demand and availability (and what it means for farmers, advisers, industry and government). In: International agricultural workforce conference. Cork, Ireland, pp 8–16

Nettle R, Kuehne G, Lee K, Armstrong D (2018a) A new framework to analyse workforce contribution to Australian cotton farm adaptability. Agron Sustain Dev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-018-0514-6

Nettle R, Crawford A, Brightling P (2018b) How private-sector farm advisors change their practices: an Australian case study. J Rural Stud 58:20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.12.027

Peaucelle J (2009) Vices et vertus du travail spécialisé. Ann Mines - Gérer Compr. https://doi.org/10.3917/geco.097.0028

Pettigrew AM (1990) The longitudinal field research on change: theory and practice. Organ Sci 1:267–292. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.3.267

Przewozny A, Bitsch V, Peters KJ (2016) Performance-based pay and other incentive schemes on dairy farms in Germany. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2851082

Roguet C, Duflot B, Graveleau C, Rieu M (2010) La mutation de la production porcine au Danemark: modèles d’élevage, performances techniques, réglementations environnementales et perspectives. Journ Rech Porc En Fr 42:59–64

Sguerzi-Boespflug M (2008) La polycompétence: bénéfices, paradoxes et enjeux stratégiques. Une étude de cas dans la grande distribution. In: 17ème Conférence internationale de management stratégique. Aims, 25p

Taylor FW (1914) The principles of scientific management. Harper, New York

Vafaï K, Anvar S (1998) Délégation et hiérarchie. Rev Économique 49:1199–1225. https://doi.org/10.2307/3502771

Ven AHVD, Poole MS (1995) Explaining development and change in organizations. Acad Manag Rev 20:510–540. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1995.9508080329

Wesarat P, Sharif MY, Majid AHA (2014) A review of organizational and individual career management: a dual perspective. Int J Hum Resour Stud 4:101–113. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v4i1.5331

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the support of Science without Frontiers, from CAPES and Ministry of Education of Brazil. Partners of this work are as follows: RMT Travail, Fédération Nationale des Syndicats d’Exploitants Agricoles, and the Syndicat Interprofessionnel Saint Nectaire.

Funding

This study was funded by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) (grant number 99999.001251/2013-09).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Malanski, P.D., Ingrand, S. & Hostiou, N. A new framework to analyze changes in work organization for permanent employees on livestock farms. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 39, 12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-019-0557-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-019-0557-3