Abstract

Brood parasites need to overcome host detection in order to exploit their target resource. Nest invasion by brood parasites is possibly enabled either by chemical mimicry (innate odour match with host), camouflage (acquired odour match with host) and/or chemical insignificance (odour reduction). We analysed which of these strategies may be used by the cuckoo bees Sphecodes monilicornis and S. puncticeps to sneak into the nests of their social Lasioglossum bee hosts. In staged dyadic encounters, the host bee workers interacted much more rarely towards S. monilicornis than towards nestmates, suggesting that the host bee may weakly detect this cuckoo bee in the nest. Cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) profiles of S. monilicornis included about 30–50% of compounds found on host bees, possessed exclusively linear alkanes, a class known to be generally less important in nestmate recognition, and lacked exclusive compounds. S. monilicornis may thus avoid recognition by hosts through chemical insignificance. On the other hand, S. puncticeps has a more complex CHC profile including several exclusive methyl-branched alkanes, though no alkenes. This cuckoo bee species does not seem to use either chemical mimicry or insignificance to invade host nests. However, only a large comparative study may elucidate the evolution of CHC adaptations in Sphecodes to their hosts’ template.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Natural enemies such as parasites and parasitoids are selected to evolve strategies aimed to reduce the probability of being detected by their hosts, and, in turn, hosts are selected to defend themselves by evolving mechanisms, e.g. to detect and escape their enemies (Poulin et al. 2000). These different selective forces lead to an evolutionary arms race between hosts and natural enemies (Dawkins and Krebs 1979; Schmid-Hempel 1998), in which reciprocal adaptations are as diverse as behavioural (e.g. Polidori et al. 2010; Foitzik et al. 2003), morphological (e.g. Ortolani and Cervo 2010) or chemical (e.g. Brandt et al. 2005; Wurdack et al. 2015).

Striking examples of the variety of strategies evolved in natural enemies to evade host defence come from parasitic aculeate Hymenoptera (bees, ants and stinging wasps) (e.g. Lenoir et al. 2001; Wurdack et al. 2015). This diverse group include brood parasitoids (females lay eggs on or into the host immatures) (O’Neill 2001), cleptoparasites (females lay eggs on the host food stores) (Michener 2007) and social parasites (reproductive females occupy and exploit the worker force of the host colony to raise their own offspring) (Lorenzi 2006).

Since chemical recognition and communication are central in both insect intra- and interspecific interactions (Howard and Blomquist 2005), several different chemical strategies have been observed in such natural enemies according to this diversity in parasitic lifestyle. In particular, studies from different lineages, particularly from wasps and ants, converged in identifying three ways in which natural enemies overcome host aggression while invading host nests. Chemical mimicry occurs when a parasite produces ex novo an odour matching that of the host, leading the host to recognize it as a conspecific (Strohm et al. 2008). Chemical camouflage, widespread in social parasites, also involves an odour match, but host odour is acquired during nest invasion (Lorenzi 2006). Chemical insignificance, on the other hand, occurs when the natural enemy shows a substantial reduction of recognition cues, so that hosts simply cannot perceive their presence in the nests (Cini et al. 2009; Uboni et al. 2012).

Cleptoparasitic (cuckoo) behaviour in bees, i.e. the use of host pollen and nectar stores to rear parasitic brood, is a widespread phenomenon evolved several times independently within at least three bee families (Michener 2007). However, compared with wasps and ants, cuckoo bee invasion strategies have been much less investigated. Mimicry, based on mandibular gland chemistry, was suggested between the cuckoo bee genus Nomada (Apidae) and its solitary host bees (Tengö and Bergström 1977). Chemical camouflage was reported in cuckoo bumblebees (Apidae: Bombus (Psythirus)) (social parasites) while invading their bumblebee host nests (Kreuter et al. 2012), and mimicry may be also involved (Martin et al. 2010). Chemical insignificance was reported in obligate social inquiline bumblebees but exclusively at the invasion stage, prior to camouflage (Dronnet et al. 2005). To develop a more comprehensive picture of parasitism strategy evolution in bees, it is thus important to investigate this topic in additional lineages.

Here, we investigated which chemical strategy may have evolved in the cuckoo bee genus Sphecodes (Halictidae), whose species are obligate parasites of ground-nesting bees. Sphecodes females sneak into the nests of both solitary and social bee hosts (Sick et al. 1994; Bogusch et al. 2006) and may remain for hours or even a few days in the host nest during a single invasion (Eickwort and Eickwort 1972; Knerer 1980), with some species reported to kill the host workers prior to egg-laying (Polidori et al. 2009). Previous observations on the interactions between Sphecodes bees and their hosts showed that, within laboratory nests or artificial arenas, the host bees are generally not very aggressive towards these cuckoo bees (Heide 1992; Polidori and Borruso 2012). Given these pieces of evidence, Sphecodes bees can be thus expected to have evolved some chemical strategy to be unrecognizable as a foe. The only previous attempt to study this possibility suggested an absence of mimicry, based on Dufour’s gland secretion chemistry (Sick et al. 1994). However, cuticular chemical profile, which is increasingly considered critical in Hymenoptera recognition and communication systems (Howard and Blomquist 2005; Leonhardt et al. 2016), has not yet been investigated in these bees.

Hence, we conducted a study on the recognition ability of host bees towards these cuckoo bees and we analysed the cuticular chemical profile of both hosts and cuckoo bees, in order to determine which chemical strategy introduced above may apply to Sphecodes cuckoo bees.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study species

Our model system includes the cuckoo bees Sphecodes monilicornis Kirby and Sphecodes puncticeps Thomson and four of their host bee species within the subgenus Evyleus of the genus Lasioglossum (Halictidae): Lasioglossum malachurum (Kirby), Lasioglossum calceatum (Scopoli), Lasioglossum laticeps (Schenck) and Lasioglossum politum (Schenck). Based on direct evidence of parasitism and/or observations of nest invasion, S. monilicornis is associated with the first three host bee species, while S. puncticeps is associated with the fourth species (Bogusch and Straka 2012). Sphecodes puncticeps seems to be ancestrally specialized in host range (two subgenera of Lasioglossum: Evylaues and Dialictus), while S. monilicornis seems to be ancestrally more generalist (at least two genera of Halictidae and Andrenidae) (Habermannová et al. 2013). All the host bee species studied here are obligate eusocial with the exception of L. calceatum, which is known to be socially polymorphic (i.e. some populations are solitary and other are eusocial) (Davison and Field 2016). On the other hand, L. laticeps has a less complex eusocial organization compared with L. malachurum and L. politum (Packer 1983). Queens of eusocial species establish their colonies in spring, followed by 1–3 worker phases and a last phase composed by males and reproductive females (Knerer 1992).

2.2 Behavioural experiments

The behavioural interactions between cuckoo and host bees were studied near Alberese, a small town inside the Maremma Regional Park (Tuscany, Italy: 42° 40′ 5″ N, 11° 6′ 23″ E), from 5 to 25 July 2008, where a nest aggregation of L. malachurum of > 1000 nests was previously studied (Polidori et al. 2009). At this site, nests are parasitized by S. monilicornis. Females of S. puncticeps were also observed to fly in the nesting area, but no evidence of parasitic interactions with L. malachurum was recorded.

Behavioural tests were performed between 900 h and 1500 h during the highest foraging activity period of the host bees and their cleptoparasites (Polidori et al. 2009). Only females of the cuckoo bees and female workers of the host bee were used. Lasioglossum malachurum females were collected while exiting from their nest, while females of S. monilicornis were collected after having visited a nest or while attempting to enter a nest. All the tested individuals were preserved and identified by specialist taxonomists (see “Acknowledgments”).

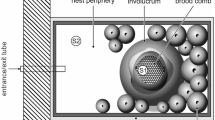

We studied the behavioural interactions between the host bees and their cuckoo bees by setting staged dyadic encounters in a circle-tube apparatus (e.g. Pabalan et al. 2000; Boesi and Polidori 2011), in order to test if the host bee reacts differently with the cuckoo bee and with a nestmate.

The circle-tube consisted of a 44-cm-long piece of clear sterile plastic tube of 0.7 cm inner diameter fashioned into circles. After having collected a pair of nestmate host bees for a trial, they were placed in the arena, first one bee and the second one after 2 min. In interspecific trials, the host bee entered first. In this way we tried to resume natural conditions, i.e. a bee worker inside its nest and a visitor (either a conspecific nestmate or a cuckoo bee) which entered the nest. Each trial lasted 15 min, a sufficient period to detect behavioural differences (Pabalan et al. 2000). Bees were handled with plastic gloves and each circle tube was used only once (Smith and Weller 1989). A total of 29 trials (19 intraspecific and 10 heterospecific trails) were performed, recording the behaviour of the bees on a tape recorder.

Previous studies showed that behaviours performed by L. malachurum in circle-tube arenas are mainly cooperative behaviours such as “mutual passing” (bees accommodate each other while they pass in opposite directions), “following” (a forward movement by a bee towards the other which walks backward through the circle tube), “stop in contact” (bees in a frontal encounter stop in contact and touch each other slowly with antennae and mandibles), with lower frequency of avoidance behaviours (“withdrawing” (WHD): a bee makes a 180° ± turn away from the other individual or backs quickly away from it), and very rare aggressions through the “C-posture” (a female curls her abdomen under the thorax with the intention to sting the other bee) and the “mandibular hold” (a female clamp the mandibles around the neck, limbs or antenna of the other bee) (Polidori and Borruso 2012). Because L. malachurum was shown to be extremely peaceful towards both nestmates and non-nestmates (Polidori and Borruso 2012), we did not use the number of aggressive interactions as a proxy for cuckoo bee vs. nestmate recognition. Instead, we counted the total number of interactions of any type (see below) as an estimate for cuckoo bee vs. nestmate detection, under the assumption that the lesser the level of interaction, the lower the detection of the other occupant on the arena. The overall number of host-parasite interactions was also used with a similar meaning in myrmecophile-ant associations (von Beeren et al. 2018). Aggressive interactions were, however, separately recorded in order to see if cuckoo bees attack the host bees in the experimental conditions. The raw behavioural data are available in the Supplementary file BehavDATA.xls.

2.3 Cuticular hydrocarbon profile (CHC)

Ten L. malachurum workers, 10 S. monilicornis females and 7 S. puncticeps females were collected by netting at the L. malachurum nest aggregation and on surrounding flowering plants. Workers of the other three host bee species (7 individuals each) were collected by netting on flowers at southern German localities in Baden-Württemberg (Freiburg (47° 59′ 41″ N, 7° 50′ 59″ E) and Ihringen (48° 02′ 35″ N, 7° 38′ 51″ E)), from end of April to end of July 2008–2010. Upon collection, individuals were killed by freezing and stored at − 20 °C until the CHCs were extracted.

To extract cuticular hydrocarbons, bees were allowed to thaw and immersed in n-hexane for 10 min (e.g. Wurdack et al. 2015). Hexane extracts were then concentrated with a gentle stream of N2 until approximately 80–100 μL of the extract remained and stored at − 20 °C. The bees were stored in 95% ethanol. CHC extracts were analysed with a HP 6890 gas chromatograph (GC) coupled to a HP 5973 Mass Selective Detector (MS) (Hewlett Packard, Waldbronn, Germany) or an Agilent 7890/5975 GC/MS System. The GC (split/splitless injector in splitless mode for 1 min, injected volume: 1 μL at 300 °C injector temperature) was equipped with a DB-5 Fused Silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID, df = 0.25 μm, J&W Scientific, Folsom, USA). Helium was used as carrier gas with a constant flow of 1 mL/min. For both GC/MS the temperature program starts at 60 °C with a subsequent increase of 5 °C/min until 300 °C and kept isotherm at 300 °C for 10 min. An ionization voltage of 70 eV (source temperature, 230 °C) was set for the acquisition of the mass spectra by electron ionization (EI-MS).

The software MSD ChemStation G1701EA E.02.02.1431 was used to record and analyse the chromatograms and mass spectra. The MS data base Wiley275 (John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA), the compound-specific retention time, Kovats indices, and the detected diagnostic ions (Carlson et al. 1998) were used to identify CHC compounds. For few substances eluting at similar retention times we combined these compounds and classified them as mixes.

In order to select peak which represents a specific species, we deleted all the compounds which add less than 0.5% to the overall relative amount within each species. If a compound shows more than 0.5% in a single species, we kept it in all investigated species for the comparative analysis. In a second step we eliminated all compounds which did not occur in at least 50% of all individuals within a species. The final matrix included 41 peaks (Table I). We also checked substances with lower abundance (> 0.1%) to verify the presence of rare compounds. Prior to the statistical analysis, we transformed all peak values to avoid undefined values for peaks with an area of zero (log10((relative peak area/geometric mean of relative peak area) + 1)) (Strohm et al. 2008, modified after Aitchison 1986). The raw chemical data are available in the Supplementary file ChemDATA.xls.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data from the behavioural experiments were not normally distributed, so that we used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by paired comparisons through Dunn’s procedure, to test for differences in the median number of interactions observed in intra- and interspecific behavioural trials.

To analyse the chemical data, we used two methods which do not require a priori grouping of species, meaning that these methods allow pattern formation which is exclusively based on CHC similarities. We first performed an agglomerative cluster analysis based on the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic means of Bray-Curtis dissimilarities, which is suitable for zero-inflated datasets (Leyer and Wesche 2007). The dissimilarity matrix was based on the proportions of the previously selected hydrocarbons as revealed by GC/MS analysis. Bray-Curtis dissimilarities were then used for ordinations using non-metric multidimensional scaling analysis (NMDS), which is a non-parametric method that avoids assuming linearity among variables (e.g. McCune et al. 2002) and whose resulting plot shows the spatial distances between individuals (i.e. their chemical differences). In the NMDS, deviations are expressed in terms of “stress”, for which values < 0.15 indicate a good fit of ordination (Kruskal and Carroll 1969). An analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) was performed to statistically test for differences between the studied species (9999 permutations). Similarity percentages (SIMPER) were calculated to identify the compounds that predominantly contributed to the Bray-Curtis dissimilarities (Clarke 1993), both overall among all species and both between all pairs of species, thus investigating which compounds differ between cuckoo bees and their host bees.

In the text and tables, mean values are expressed with their standard error (SE). The statistical analysis was performed in XLSTAT 2008 and in PAST 3.04 (Paleontological Statistics Software Package, Hammer et al. 2001).

3 Results

3.1 Do L. malachurum workers recognize Sphecodes cuckoo bees as foes?

Individuals placed in the circle tubes started to interact generally within 1–2 min from the start of the experiments (Figure 1A). Overall we recorded 541 interactions, most of them cooperative/tolerant (349, i.e. 64.3% of the total number of interactions). Aggressive interactions were rare (45, i.e. 8.3% of the total). The remaining interactions (147) showed avoidance behaviour. Lasioglossum malachurum interacted much more with a conspecific than with S. monilicornis (24.6 ± 3.2 vs. 3.2 ± 1.0 interactions/trial) (Figure 1B). Sphecodes monilicornis did start few interactions with the host bee (4.4 ± 1.7). Overall, the number of interactions performed by L. malachurum towards L. malachurum, L. malachurum towards S. monilicornis and S. monilicornis towards L. malachurum significantly differed (Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2 = 26.3, df = 2, P < 0.0001), but not in interspecific trials (Dunn’s procedure, P = 0.82). Almost all cooperative interactions were expressed as “passing” and “following” (91.7%, n = 349), while the few recorded aggressive behaviours were mainly performed by the cuckoo bee (60%, n = 45) (Figure 1A). The host bee rarely attacked the cuckoo bee (3.1%, n = 45) and if so, then only in response to cuckoo bee’s aggression.

(A) S. monilicornis and L. malachurum interacting in the circle-tube arena (the cuckoo bee is attacking the host bee by holding its neck with mandibles). (B) Box-and-whisker plots showing medians (horizontal lines within boxes), 1° and 3° quartile (horizontal lines closing the boxes), and maximum and minimum values (ends of the whiskers) for the number of behavioural interactions recorded in circle-tube experiments. Lm → Lm: behaviours of L. malachurum directed towards L. malachurum; Lm → Sm: behaviours of L. malachurum directed towards S. monilicornis; Sm → Lm: behaviours of S. monilicornis directed towards L. malachurum. Different letters above the bars were used to show the results of the multiple pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s procedure.

3.2 Comparison of Sphecodes CHC profiles with Lasioglossum CHC profiles

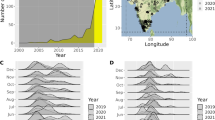

Linear alkanes, alkenes, monomethyl-branched alkanes and dimethyl-branched alkanes with chain lengths ranging from 21 to 31 carbon atoms (Table I, Figure 2 and S Figure 1) occurred as main components on the cuticle of all studied bees. Overall, linear alkanes clearly dominated the CHC profiles of studied species, while the rarest substance class was dimethyl-branched alkanes (Table I, Figure 2).

Main characteristics of the CHC profile of the studied species, when associated with their phylogenetic relationships (shown on the left, together with their host groups (for Sphecodes spp.) and their sociality (for Lasiglossum spp.)). Dashed grey lines connect the cuckoo bee species with their respective host species. The total number of peaks that make up > 0.5% per individual and are present in at least half of the group (see Section 2) and the mean relative % of each compound class are shown in correspondence with each species. Phylogenetic relationships follow Danforth et al. (2003).

Sphecodes monilicornis was by far the species with the lowest number of peaks (9), while S. puncticeps had 22 peaks and the host bee species had 17–27 peaks (Table I, Figure 2). Overall, no exclusive compounds were found in S. monilicornis, i.e. all of its compounds were found in at least one Lasioglossum species. Thus, its CHC profile is basically a subgroup (about 30–50%, depending on the host-cuckoo pair) of the host bee CHC profiles. On the other hand, S. puncticeps has 5 exclusive compounds which do not occur in any of the studied Lasioglossum species; this number increases if we only consider its unique host, L. politum, which lacks 10 compounds occurring in its associated cuckoo bee (Table I). Sphecodes monilicornis presented a CHC profile exclusively composed of linear alkanes. Sphecodes puncticeps, on the other hand, has a more complex profile with additionally methyl-branched alkanes, mainly monomethyl-branched alkanes, though no alkenes (Table I, Figure 2). The two Sphecodes species shared 9 compounds, which corresponded to the whole profile of S. monilicornis (Table I).

Lasioglossum species have even more complex profiles compared with Sphecodes, since they also include large proportions (5–32%) of alkenes, in addition to the abundant linear alkanes and, with the exception of L. laticeps, methyl-branched alkanes (Table I, Figure 2). Furthermore, much rarer compounds (below the 0.5% threshold criterion) from additional substance classes (alkadienes) were only found on Lasioglossum species. Overall, the number of compounds shared by all host bee species was 7, which corresponds to about 40% of the compounds found in L. politum, the species with the lowest number of compounds (Table I).

The cluster analysis (Figure 3) showed a first bifurcation between the individuals of S. puncticeps and all other species. Then, all individuals of L. malachurum and L. calceatum, plus 4 individuals of L. politum, are separated from the rest of individuals of the latter and S. monilicornis (Figure 3). Thus, at least a part of the cluster is congruent with the phylogenetic relationships among Lasioglossum species, i.e. their hierarchy (L. laticeps + (L. malachurum + L. calceatum)) (Figures 2 and 3). On the other hand, the two cuckoo bee species were largely separated in the cluster, in contrast to their close phylogenetic relationship.

The NMDS shows species-specific CHC profiles except for L. politum which overlaps to some extent with S. monilicornis (stress = 0.14) (Figure 4A). Indeed, the mean ranked distance between species was much larger (648.8) than the mean ranked distance within species (102.2) (Figure 4B). However, the ANOSIM test reveals a species-specific profile for all investigated species (R2 = 0.97, P = 0.0001) (Figure 4A). In detail, ANOSIM’s R2 were > 0.8 for all paired distances between species except for the distance of S. monilicornis towards L. politum (R2 = 0.78) (Table II). The SIMPER analysis reveals that alkenes and monomethyl-branched alkanes contribute most to species-species dissimilarities, while linear alkanes, except for few paired comparisons (5 out of 15), are less important (Table II, S Figure 2). This is true for the comparison between different Lasioglossum species and between Lasioglossum and Sphecodes species. Interestingly, while the differences between S. monilicornis and its three hosts rely almost exclusively on alkenes, the differences between S. puncticeps and its host rely exclusively on monomethyl-branched alkanes (Table II). Obviously, the dissimilarity between the two Sphecodes species does not depend on alkenes, while both species lack of this substance class (Table II).

4 Discussion

The hypothesis that Sphecodes cuckoo bees (as well as other closely related genera within the subtribe Sphecodina, such as Microsphecodes) may use a chemical strategy to avoid host aggression during nest invasion was initially suggested by behavioural studies showing that some species of cuckoo bees can stay in the host nests for hours or even days together with their hosts (Eickwort and Eickwort 1972; Knerer 1980). During nest invasion, the cuckoo female may kill the adult workers and eject them from the nest (Marchai 1890; Knerer and Atwood 1967; Polidori et al. 2009) or share the nest with host workers provisioning the brood of the parasite (which replaced the killed host brood) (Sakagami and Moure 1962; Eickwort and Eickwort 1972). It is likely that cuckoo bees would be attacked if recognized by the host, given that in social Lasioglossum the guards at nest entrances allow only nestmates to enter on the basis of differences in odours (Bell 1974; Bell and Hawkins 1974; Smith and Weller 1989), although the discrimination ability may change in its strength among species (Smith and Breed 1995; Soro et al. 2011; Polidori and Borruso 2012). Thus, we hypothesised in the present study that cuckoo bees evolved a chemical strategy to sneak into host nests bypassing any host discrimination.

Here, we provide evidence that the strategy used by at least one of the two studied cuckoo bee species, S. monilicornis, may be chemical insignificance. Chemical insignificance was previously reported among bees only in obligate social inquiline bumblebees at the invasion stage, prior to camouflage (Dronnet et al. 2005). Thus, this would be the first observation of this type of strategy for cleptoparasitic bees. Our conclusions for this species are supported by both the behavioural and the chemical data, as discussed below.

The circle-tube experiments support the hypothesis that S. monilicornis cuckoo bees are not recognized either as foes or as a nestmate (which would imply a camouflage strategy) by their host bees. In fact, L. malachurum showed weak interest in interacting with the cuckoo bee. Heide (1992) also reports similar interactions between Sphecodes hyalinatus Hagens and its solitary host Lasioglossum fratellum (Perez). On the other hand, S. monilicornis attacks sometimes the host bee, a behaviour which normally occurs during nest invasion (Polidori et al. 2009), and the very few aggressions by the host bee were indeed responses towards these attacks. These results may explain why under field conditions fights between Sphecodes and Lasioglossum may occur during a nest attack (Sick et al. 1994). The cuckoo bee enters the nest by attacking the guard bee first, which evokes an aggressive response by the host bee.

However, L. malachurum workers are very peaceful in circle tubes, rarely showing aggression towards both nestmate and non-nestmate conspecifics (Polidori and Borruso 2012), while the general trend for social species in similar experiments is to be tolerant towards nestmates but aggressive towards non-nestmates (e.g. Pabalan et al. 2000; Boesi and Polidori 2011). Indeed, social parasites have to camouflage themselves by acquiring the host colony odours in order to escape such finely developed nestmate recognition (Turillazzi et al. 2000; Cini et al. 2011; Kreuter et al. 2012). Lasioglossum malachurum may not have a strong nestmate recognition ability and this is in accordance with the frequent shifts of workers observed among nests (Paxton et al. 2002). However, this halictid bee still seems to have the ability to discriminate between conspecifics and heterospecifics, given that defensive reactions were observed in the field against both Sphecodes and other natural enemies such as mutillid wasps (Polidori et al. 2009). In an experimental context such as nest-mimicking circle-tube arenas, however, the very few interactions observed suggest that the presence of S. molinilicornis is weakly detected.

The CHC composition of S. molinilicornis showed that a strong mimicry or camouflage by Sphecodes has to be excluded, since no strong resemblance of CHCs between the parasites and their hosts was found. Instead, the chemical data support the hypothesis of chemical insignificance as a strategy. Overall, our chemical results show for S. molinilicornis one of the simplest CHC profiles in aculeate parasitic hymenopterans.

First, S. molinilicornis presented a much lower number of peaks than their hosts, a pattern also observed in the solitary velvet ant Mutilla europea L., a cleptoparasite of social paper wasps which is chemically insignificant (Uboni et al. 2012), as well as in socially parasitic paper wasps and socially parasitic ants before host colony invasion/integration, when they are chemically insignificant (Lorenzi et al. 2004; Lenoir et al. 2001).

Second, S. molinilicornis CHC profile is almost exclusively composed of linear alkanes. This pattern is similar to that observed in the social parasitic ant Polyergus breviceps (Emery), in which newly mated queens, before host colony invasion (i.e. when it has an insignificant profile), possess only six hydrocarbons of which five are linear alkanes (Johnson et al. 2001). Similarly, the socially parasitic hornet Vespa dybowskii (André) lays eggs that are, in contrast to those of its host, covered almost exclusively by linear alkanes and are therefore probably insignificant (Martin et al. 2008). In other cases of chemical insignificance, parasites seemed to rely more on reducing the amount of hydrocarbons rather than on excluding entire substance classes (Uboni et al. 2012; Lorenzi and Bagnères 2002; Lorenzi et al. 2004). Furthermore, in most of the known cases of chemical insignificance, parasites possess at least a species-specific set of compounds not present in their hosts (e.g. Bagnères et al. 1996; Turillazzi et al. 2000), while in our study this was not seen for this cuckoo bee species.

The strongly linear alkane-based CHC profile of S. molinilicornis supports the insignificance hypothesis, since alkanes are known to be the substance class less likely involved in nestmate discrimination/recognition in social Hymenoptera (Dani et al. 2001; Dani et al. 2005). For example, kin-based odour differences in L. malachurum are mainly based on linear alkanes (Soro et al. 2011), but because of their simple structure, these substances might have lower information content compared with alkenes and methyl-branched alkanes (Breed 1998; Dani et al. 2001, 2005). Furthermore, alkenes, which S. molinilicornis lacks but are abundant in their hosts, are known to play an important role in various recognition systems both as species-specific pheromones and for nestmate recognition in eusocial insects (van Zweden and d’Ettorre 2010). Thus, it is also not surprising that chemical distances between pairs of Lasioglossum species in this study were mainly driven by alkenes.

Further evidence supporting the insignificance hypothesis in S. molinilicornis comes from Sick et al. (1994), who showed in fact that Dufour’s gland extracts of six Sphecodes species lacked macrocyclic lactones, which are dominant in their hosts’ glands, and lactones were suggested to have an important role in different Lasioglossum communication contexts, e.g. queen dominance (Smith and Weller 1989).

Although there is evidence for chemical insignificance in S. molinilicornis, the chemical data of our study do not support the insignificance hypothesis for the other cuckoo bee species, S. puncticeps. This species has a complex CHC profile, very similar to that of Lasioglossum species in terms of number of peaks and diversity of substance classes, but it largely diverges from all tested species in CHC composition. However, this species is similar to S. monilicornis in lacking alkenes. Possibly, the insignificance strategy in Sphecodes cuckoo bees is based on the absence of alkenes, which are known to be very important in communication in other insect species (van Zweden and d’Ettorre 2010). However, these cuckoo bee species possess many methyl-branched alkanes, also strongly related to communication in insects (Breed 1998; Dani et al. 2001, 2005). It is thus not possible at the moment to accept the insignificance hypothesis for S. puncticeps.

We have also detected similarities between CHCs of S. monilicornis and L. politum, which, however, is not reported as a host for this cuckoo bee. On the other hand, L. politum is a host of S. puncticeps, which did not show any evident chemical strategy in this study. We cannot exclude that cuckoo bees also use a weak mimicry or camouflage strategy, to an extent perhaps related to the degree of host specialization. Indeed, an association between specialization level and a parasite’s chemical strategy is expected: while specialist natural enemies often show mimicry (e.g. Strohm et al. 2008; Wurdack et al. 2015), generalist natural enemies more likely evolve chemical insignificance (e.g. Uboni et al. 2012; Parmentier et al. 2017). Although we have found several lines of evidence for a chemical insignificance strategy in S. monilicornis, we cannot exclude an coevolutionary arms race and signs of local adaptation between parasites and hosts on a population level (e.g. Lenoir et al. 2001; Casacci et al. 2019), since (except for S. monilicornis and L. malachurum) we had no access to hosts and parasites at the host nesting sites for our chemical comparison. From this point of view, and given its higher degree of host specialization, S. puncticeps may perhaps show both insignificance and even mimicry at a given host aggregation via local adaptations. In future, a comparative study with a broader sample of Sphecodes and their host species from different populations will provide a better understanding of the possible link between chemical strategies and host specialization and of potential local adaptation.

References

Aitchison, J. (1986) The Statistical Analysis of Compositional Data. Monographs in statistics and applied probability. London: Chapman and Hall.

Bagnères, A.-G., Lorenzi, M. C., Clément, J.-L., Dusticier, G., Turillazzi, S. (1996) Chemical usurpation of a nest by paper wasp parasites. Science 272, 889–892

Bell, W. J. (1974) Recognition of resident and non-resident individuals in intraspecific nest defense of a primitively eusocial halictine bee. J. Comp. Physiol. 93, 195–202

Bell, W. J., Hawkins, W. A. (1974) Patterns of intraspecific agonistic interactions involved in nest defense of a primitively eusocial halictine bee. J. Comp. Physiol. 93, 183–193

Boesi, R., Polidori, C. (2011) Nest membership determines the levels of aggression and cooperation between females of a supposedly communal digger wasp. Aggress. Behav. 37, 405–416

Bogusch, P., Straka, J. (2012). Review and identification of the cuckoo bees of central Europe (Hymenoptera: Halictidae: Sphecodes). Zootaxa 3311, 1–41

Bogusch, P., Kratochvíl, L., Straka, J. (2006). Generalist cuckoo bees are species specialist at the individual level (Hymenoptera: Apoidea, Sphecodes). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 60, 422–429

Brandt, M., Heinze, J., Schmitt, T., Foitzik, S. (2005) A chemical level in the coevolutionary arms race between an ant social parasite and its hosts. J. Evol. Biol. 18, 576–586

Breed, M. D. (1998) Chemical cues in kin recognition: criteria for identification, experimental approaches, and the honey bee as an example, in: Vander Meer R. K., Breed M. D., Espelie K. E, Winston M. L. (Eds.), Pheromone communication in social insects. Westview, Boulder, pp. 56–78

Carlson, D. A., Bernier, U. R., Sutton, B. D. (1998) Elution patterns from capillary GC for methyl-branched alkanes. J. Chem. Ecol. 24, 1845–1865

Casacci L. P., Schönrogge, K., Thomas, J. A., Balletto, E., Bonelli, S. & Barbero, F. (2019) Host specificity pattern and chemical deception in a social parasite of ants. Sci. Rep. 9, Article number: 1619, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38172-4.

Cini, A., Gioli, L., Cervo, R. (2009) A quantitative threshold for nestmate recognition in a paper social wasp. Biol. Lett. 5, 459–461

Cini, A., Bruschini, C., Signorotti, L., Pontieri, L., Turillazzi, S., Cervo, R. (2011) The chemical basis of host nest detection and chemical integration in a cuckoo paper wasp. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3698–3703

Clarke, K. R. (1993) Non-parametric multivariate analysis of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 18, 117–143.

Danforth, B. N., Conway, L., Ji, S. (2003) Phylogeny of eusocial Lasioglossum reveals multiple losses of eusociality within a primitively eusocial clade of bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). Syst. Biol. 52, 23–36.

Dani, F. R., Jones, G. R., Destri, S., Spencer, S. H., Turillazzi, S. (2001) Deciphering the recognition signature within the cuticular chemical profile of paper wasps. Anim. Behav. 62, 165–171

Dani, F. R., Jones, G. R., Corsi, S., Beard, R., Pradella, D., Turillazzi, S. (2005) Nestmate recognition cues in the honey bee: differential importance of cuticular alkanes and alkenes. Chem. Senses 30, 477–489

Davison, P. J., Field, J. (2016) Social polymorphism in the sweat bee Lasioglossum (Evylaeus) calceatum. Insect. Soc. 63, 327–338

Dawkins, R., Krebs, J. R. (1979) Arms races between and within species. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 205, 489–511

Dronnet, S., Simon, X., Verhaeghe, J. C, Rasmont, P., Errard, C. (2005) Bumblebee inquilinism in Bombus (Fernaldaepsithyrus) sylvestris (Hymenoptera, Apidae): behavioural and chemical analyses of host-parasite interactions. Apidologie 10, 59–70

Eickwort, G. C., Eickwort, K. R. (1972) Aspects of the biology of Costa Rican Halictine bees. II1. Sphecodes kathleenae, a social kleptoparasite of Dialictus umbripennis (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). J. Kans. Entomol. Soc. 45, 529–541

Foitzik, S., Fischer, B., Heinze, J. (2003) Arms races between social parasites and their hosts: geographic patterns of manipulation and resistance. Behav. Ecol. 14, 80–88.

Habermannová, J., Bogusch, P., Straka, J. (2013) Flexible host choice and common host switches in the evolution of generalist and specialist cuckoo bees (Anthophila: Sphecodes). PLoS ONE 8, e64537

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T., Ryan, P. D. (2001) PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Version 2.15. Paleontol. Eletronica 4, 9. http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm.

Heide, A. v. D. (1992) Zur Bionomie yon Lasiogtossum (Evylaeus) fratellum (P6rez), einer Furchenbiene mit ungew6hnlich langlebigen Weibchen (Hymenoptera, Halictinae). Drosera 92, 89–206

Howard, R. W., Blomquist, G. J. (2005) Ecological, behavioral, and biochemical aspects of insect hydrocarbons. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 50, 371–393

Johnson, C. A., Vander Meer, R. K., Lavine, B. (2001) Changes in the cuticular hydrocarbon profile of the slave-maker ant queen, Polyergus breviceps Emery, after killing a Formica host queen (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 27, 1787–1804

Knerer, G. (1980) Biologie und Sozialverhalten von Bienenarten der Gattung Halictus Latreille (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). Zool. Jb. Syst. 107, 511–536

Knerer, G. (1992) The biology and social behaviour of Evylaeus malachurus (K.) (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) in different climatic regions in Europe. Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Syst. Oekol. Geogr. Tiere 119, 261–290

Knerer, G., Atwood, C. E. (1967) Parasitization of social halictine bees in southern Ontario. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Ontario 97, 103–110

Kreuter, K., Bunk, E., Lückemeyer, A., Twele, R., Francke, W., Ayasse, M. (2012) How the social parasitic bumblebee Bombus bohemicus sneaks into power of reproduction. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 66, 475–486

Kruskal J., Carroll J. D. (1969) Geometrical models and badness-of-fit functions. In Multivariate analysis (P. R. Krishnaiah, Ed.), pp. 639–671. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Lenoir, A., d’Ettorre, P., Errard, C., Hefetz, A. (2001) Chemical ecology and social parasitism in ants. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 46, 573–599

Leonhardt, S. D., Menzel, F., Nehring, V., Schmitt, T. (2016) Ecology and evolution of communication in social insects. CELL 164, 1277–1287

Leyer, I., Wesche, K. (2007) Multivariate Statistik in der Ökologie. Berlin: Springer.

Lorenzi, M. C. (2006) The result of an arms race: the chemical strategies of Polistes social parasites. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 43, 550–563

Lorenzi, M. C., Bagnères, A.-G. (2002) Concealing identity and mimi-cking hosts: A dual chemical strategy for a single social parasite? (Polistes atrimandibularis, Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Parasitology 125, 507–512

Lorenzi, M. C., Cervo, R., Zacchi, F., Turillazzi, S., Bagnères, A.-G. (2004) Dynamics of chemical mimicry in the social parasite wasp Polistes semenowi (Hymenoptera Vespidae). Parasitology 129, 643–651.

Marchai, P. (1890) Formation d’une espece par le parasitisme. Etude sur le Sphecodes gibbus. Rev. Scient. 45, 199–204

Martin, S. J., Takahashi, J., Ono, M., Drijfhout, F. P. (2008) Is the social parasite Vespa dybowskii using chemical transparency to get her eggs accepted? J. Insect Physiol. 54, 700–707

Martin, S. J., Carruthers, J. M., Williams, P. H., Drijfhout, F. P. (2010) Host specific social parasites (Psithyrus) indicate chemical recognition system in bumblebees. J. Chem. Ecol. 36, 855–863

McCune, B., Grace, J., Urban, D. (2002) MjM Software Design. Analysis of Ecological Communities. Gleneden Beach, Oregon.

Michener, C. D. (2007) The bees of the World. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

O’Neill, K.M. (2001) Solitary Wasps: Natural History and Behavior. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Ortolani, I., Cervo, R. (2010) Intraspecific body size variation in Polistes paper wasps as a response to social parasitism pressure. Ecol. Entomol.35, 352–359

Pabalan, N., Davey, K. G., Packer, L. (2000) Escalation of aggressive interactions during staged encounters in Halictus ligatus Say (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), with a comparison of circle tube behaviors with other halictine species. J. Insect. Behav. 13, 627–650

Packer, L. (1983) The nesting biology and social organisation of Lasioglossum (Evylaeus) laticeps (Hymenoptera, Halictidae) in England. Insect. Soc. 30, 367–375

Parmentier, T., Dekoninck, W., Wenseleers, T. (2017) Arthropods associate with their red wood ant host without matching nestmate recognition cues. J. Chem. Ecol. 43, 644–61

Paxton, R. J., Ayasse, M., Field, J., Soro, A. (2002) Complex sociogenetic organization and reproductive skew in a primitively eusocial sweat bee, Lasioglossum malachurum, as revealed by microsatellites. Mol. Ecol. 11, 2405–2416

Polidori, C., Borruso, L. (2012) Socially peaceful: foragers of the eusocial bee Lasioglossum malachurum are not aggressive against non-nestmates in circle-tube arenas. Acta Ethol. 15, 15–23

Polidori, C., Borruso, L., Boesi, R., Andrietti, F. (2009) Segregation of temporal and spatial distribution between kleptoparasites and parasitoids of the eusocial sweat bee, Lasioglossum malachurum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae, Mutillidae). Entomol. Sci. 12, 116–129

Polidori, C., Bevacqua, S., Andrietti, F. (2010) Do digger wasps time their provisioning activity to avoid cuckoo wasps (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae and Chrysididae)? Acta Ethol. 13, 11–21.

Poulin, R., Morand, S., Skorping, A. (2000) Evolutionary biology of host–parasite relationships: theory meets reality. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Sakagami, S. F., Moure, J. S. (1962) Sphecodes russeiclypeatus, n. sp., obtido de um ninho de Dialictus (Chloralictus) seabrai (Moure, 1956) (Hymenoptera-Apoidea). Bol. Univ. Paraná, Zool. 1, 1–6

Schmid-Hempel, P. (1998) Parasites in social insects. : Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Sick, M., Ayasse, M., Tengö, J., Engels, W., Lübke, G., Francke, W. (1994) Host-parasite relationships in six species of Sphecodes bees and their halictid hosts: Nest intrusion, intranidal behavior, and Dufour’s gland volatiles. J. Insect Behav. 7, 101–117

Smith, B. H., Breed, M. D. (1995) The chemical basis for nest-mate recognition and mate discrimination in social insects. In: Cardé R. T., Bell W. J. (Eds.), Chemical ecology of insects 2. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 287–317

Smith, B. H., Weller, C. (1989) Social competition among gynes in Halictine bees – the influence of bee size and pheromones on behavior. J Insect Behav. 2, 397–411

Soro, A., Ayasse, M., Zobel, M. U., Paxton, R. J. (2011) Kin discriminators in the eusocial sweat bee Lasioglossum malachurum: the reliability of cuticular and Dufour’s gland odours. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 641–653

Strohm, E., Kroiss, J., Herzner, G., Laurien-Kehnen, C., Boland, W., Schreier, P., Schmitt, T. (2008) A cuckoo in wolves’ clothing? Chemical mimicry in a specialized cuckoo wasp of the European beewolf (Hymenoptera, Chrysididae and Crabronidae). Front. Zool. 5, 2.

Tengö, J., Bergström, G. (1977) Cleptoparasitism and odor mimetism in bees: Do Nomada males imitate the odor of Andrena females? Science 196, 1117–1119

Turillazzi, S., Sledge, M. F., Dani, F. R., Cervo, R., Massolo, A., Fondelli, L. (2000) Social hackers: integration in the host chemical recognition system by a paper wasp social parasite. Naturwissenschaften 87, 172–176.

Uboni, A., Bagnères, AG., Christidès, J. P., Lorenzi, C. M. (2012) Cleptoparasites, social parasites and a common host: chemical insignificance for visiting host nests, chemical mimicry for living in. J. Insect Physiol., 58, 1259–1264

van Zweden, J. S., d’Ettorre, P. (2010) Nestmate recognition in social insects and the role of hydrocarbons. G. J. Blomquist, A.-G. Bagnères (Eds.), Insect Hydrocarbons. Biology, Biochemistry, and Chemical Ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 222-243

von Beeren, C., Brückner, A., Maruyama, M., Burke, G., Wieschollek, J., Kronauer, D. J. C. (2018) Chemical and behavioral integration of army ant-associated rove beetles – a comparison between specialists and generalists. Front. Zool. 15, 8

Wurdack, M., Herbertz, S., Dowling, D., Kroiss, J., Strohm, E., Baur, H., Niehuis, O., Schmitt, T. (2015) Striking cuticular hydrocarbon dimorphism in the mason wasp Odynerus spinipes and its possible evolutionary cause (Hymenoptera: Chrysididae, Vespidae). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci.282, 20151777

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Maximilian Schwarz and Andreas Ebmer, who kindly identified the specimens. Thanks are due to the administration office at Maremma Regional Park for issuing the permits necessary to carry out the fieldwork. We are indebted to Marco Marandola for helping in field data collection and to Marie Christine Melchior for helping in CHC extraction and GC/MS analysis. Experiments comply with the current Italian and German laws.

Funding

The study was funded by a project of Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (España) (CGL2017- 83046-P). CP was funded with a post-doctoral contract from the Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha and the European Social Fund (ESF) and by a mobility fellowship from the Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha (2016-II Call).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CP and TS conceived the study and designed the experiments; CP and TS collected the sample and the data; CP, TS and MG performed the experiments and the analyses; CP took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Manuscript editor: James Nieh

L’abeille coucou, Sphecodes, utilise-t-elle un camouflage chimique pour envahir les nids de leurs hôtes sociaux Lasioglossum ?

Halictidae / Sphecodes / Lasioglossum / cleptoparasitisme / camouflage chimique.

Benutzen Sphecodes Kuckucksbienen chemische Unscheinbarkeit, um in die Nester ihrer Lasioglossum Wirte einzudringen ?

Halictidae / Sphecodes / Lasioglossum / Kleptoparasitismus / chemische Unscheinbarkeit.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Polidori, C., Geyer, M. & Schmitt, T. Do Sphecodes cuckoo bees use chemical insignificance to invade the nests of their social Lasioglossum bee hosts?. Apidologie 51, 147–162 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00692-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00692-x