Abstract

Introduction

Post-inflammatory erythema (PIE) and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) are the most common acne-related sequelae with no effective treatments. By combining different cut-off filters, intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy can effectively treat these conditions with few side effects. While the safety and effectiveness of IPL for treating post-burn hyperpigmentation is well known, there is little evidence for its benefits for acne-related PIH. In this article, we evaluate the efficacy and safety of IPL for the treatment of acne-related PIE and PIH.

Methods

This retrospective study evaluated 60 patients with more than 6 months of PIE and PIH treated by the same IPL device and similar protocols. The treatment included three to seven sessions at 4–6-week intervals, and three cut-off filters (640 nm, 590 nm and 560 nm) were used sequentially in each session. Using the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS), Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI), and Erythema Assessment Scale (EAS), patients were evaluated on the basis of their facial photographs. The facial brown spots and red areas were visualised and analysed using the VISIA-CR system. Six months after the last treatment, the patients were assessed for acne relapse or any side effects.Please check and confirm that the authors and their respective affiliations have been correctly processed and amend if necessary.Checked and confirmed. No further corrections.

Results

On the basis of the GAIS, 49 of 60 patients (81.7%) showed complete or partial clearance of erythema and hyperpigmentation. The CADI and EAS scores showed significant improvement (p < 0.01) after IPL treatment compared with pre-treatment. A significant reduction (p < 0.01) in the facial brown spots and red areas was seen after IPL treatment. While no long-term side effects were reported, seven patients (11.7%) experienced acne relapse at follow-up.

Conclusion

IPL is an effective and safe treatment for acne-related PIE and PIH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since post-inflammatory erythema (PIE) and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) are the most common acne-related sequelae with no effective treatments, treatment using energy-based devices is increasingly preferred by physicians and patients because of their effective performance, short downtime, and fewer adverse effects. |

By combining different cut-off filters, we found significant improvement in PIE and PIH using intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy. |

IPL could be an effective and safe therapeutic option for acne-related PIE and PIH, with few side effects. |

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common types of acne, with an incidence as high as 85% in adolescent men and women. However, 12% of women and 3% of men remain affected until middle age [1]. Owing to time-consuming and cost-intensive treatments, patients suffer from significantly reduced quality of life and serious psychological problems [2, 3]. Adolescent patients, especially, often suffer from stigma, anxiety, depression, withdrawal, discrimination and other psychological distress due to facial acne. The impact of acne, which exceeds that of asthma and epilepsy, makes it difficult for adolescents to integrate into a group [4].Please confirm the section headings are correctly identified.Confirmed.

The skin lesions of acne vulgaris tend to occur on the face. Owing to chronic inflammation, the patients experience pain, itching and various sequelae. The most common acne-related sequelae are post-inflammatory erythema (PIE) and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), which often present together. PIE consists of telangiectasia and erythematous papules, usually present after the clearance of inflammatory acne. These vascular lesions are mainly located very close to the skin surface and have a red appearance due to the concentration of minor blood vessels in that area [5]. Although facial PIE very slowly improves with time, in some cases, it is never completely cleared [6]. Acne-related PIH presents as localised or diffuse brown-to-grey-brown macules at sites of acne lesions and becomes most apparent after PIE has resolved. An Asian Acne Board study found PIH in 58.2% of patients with acne. Besides, PIH persists for at least 1 year in more than 50% of these patients and 5 years or longer in 22.3% of patients [7]. However, to date, no criteria are available for predicting the outcome of PIH/PIE, which is cosmetically unacceptable for patients and leads to psychological distress. Conventional treatments, such as chemical peeling and isotretinoin, are effective in treating PIE and PIH, but the long treatment period and adverse reactions are often difficult to tolerate.

Intense pulsed light (IPL) has been widely used to treat a variety of skin pigmentation and vascular diseases. IPL devices are broadband-filtered xenon flashlamps based on selective photothermolysis. Most IPL devices emit 400–1200 nm wavelengths targeting porphyrin, melanin, haemoglobin and water. Recent studies have reported the successful application of IPL for acne treatment [8,9,10].

Despite these available treatment options, an effective and safe procedure for managing acne that resolves its vascular sequelae and reduces pigmentary disorders is still needed. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and largest study that evaluates the long-term effects of IPL treatment on acne-induced PIE and PIH.

Methods

Study Design

Patients treated using IPL in our department between January 2020 and December 2021 were screened for the following criteria: diagnosed with acne-induced PIE and PIH for more than 6 months without self-relieving trends, no combined therapy, a unified treatment protocol (use of the same IPL devices, cut-off filters and treatment intervals), and at least 6 months of follow-up. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to the initiation of IPL treatment. The procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. Finally, 60 patients were included in this retrospective analysis.

Treatment

The wavelength spectrum of the IPL device (BBL, Sciton, Inc, Palo Alto, CA) used in this study ranged from 400 to 1200 nm. Three cut-off filters were sequentially used in each session: 640 nm (8–12 J/cm2, 30–35 ms), 590 nm (8–12 J/cm2, 15–20 ms) and 560 nm (6–10 J/cm2, 12–15 ms), cooling to 12–15 °C, one pass, with 10–20% overlap. The treatments involved three to seven sessions at 4–6-week intervals depending on the severity of acne in each patient. No topical anaesthesia was required prior to IPL irradiation. A 5–8-mm-thin layer of coupling gel was applied to the entire face. Following the procedure, patients were advised to use an ice bag for 15 min. Sunscreen is recommended 2 weeks before the procedure and thereafter.

Evaluations

Photographs were taken with a digital camera (60D camera; Canon, Tokyo, Japan) and VISIA-CR (Canfield Scientific, Fairfield, NJ) before each session and 6 months after the final session. The patients filled out a questionnaire on-site or remotely, including the 5-point Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) [11] and Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) [12]. Two independent dermatologists evaluated the Erythema Assessment Scale (EAS) [13] on the basis of the patients’ photographs. The persistence or clearing of lesions was evaluated on the basis of visual examination using standardised photography and quantitative analysis using the VISIA digital imaging system. Post-treatment responses including erythema, oedema and other side effects were recorded for each patient.

Data Analysis

The data obtained were analysed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The non-normal data (CADI, EAS and brown spots) were evaluated using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Differences in the normally distributed data (red areas) were compared using paired t-test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

A total of 60 patients (52 women and 8 men) were included in this retrospective analysis. The mean age of the participants was 29 (range 22–37) years. While 38 patients (63.3%) had a Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) III, 22 (36.7%) had an FST IV. Thirty-five patients (58.3%) had PIE and PIH for > 6 months but < 12 months, while 25 (41.7%) had them for > 12 months. While 1 patient (2%) received 7 sessions of treatment, 2 (4%), 34 (56.7%), 11 (18.3%) and 12 patients (20%) received 6, 3, 4, and 5 sessions, respectively.

GAIS, CADI and EAS

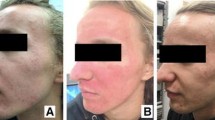

Two participants demonstrated ‘exceptional improvement’, and one, shown in Fig. 1a, had almost total clearing of PIE and PIH along with an overall rejuvenated appearance (tone, glossiness and laxity). Further, 21 participants (35%, Fig. 1b) were assessed as ‘very improved’, while 26 (43.3%, Fig. 1c) had ‘improved’ and 11 (18.3%) remained ‘unaltered’. In short, 49 of 60 patients (81.7%) showed complete or partial clearance of erythema and hyperpigmentation.

Improvement of facial PIE and PIH. Photographs before (a, c) and after (b, d) IPL treatment show improvement in facial PIE and PIH. In addition, visual examination shows clearance of PIE and PIH, reduced acne lesions, and improvement in skin texture and tone. 1A, GAIS = 1, exceptional improvement; 1B, GAIS = 2, marked improvement; 1C, GAIS = 3; improvement. IPL intense pulsed light, PIE post-inflammatory erythema, PIH post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, GAIS Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale

In accordance with the GAIS trends, compared with the baseline, the CADI at follow-up (6 months after the last session) showed significant improvement (Fig. 2a). The overall mean CADI score before IPL treatment was 9 (IQR 7–10), suggesting moderate quality of life (QOL) impairment. However, at the end of follow-up, the mean CADI score was 7 (6–8), suggestive of mild QOL impairment and significant improvement (p < 0.01). The EAS was also significantly reduced after the IPL treatments (Fig. 2b, p < 0.01).

Changes in CADI and EAS scores following IPL treatment. The CADI (a) and EAS (b) scores before and after IPL treatment are shown. Since these scores did not conform to a normal distribution, the data are shown using median (IQR) and were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. **p < 0.01. IPL intense pulsed light, CADI Cardiff Acne Disability Index, EAS Erythema Assessment Scale

VISIA-CR Images

The facial photographs of 17 patients were recorded with the VISIA-CR digital imaging system at baseline and the end of follow-up. The red facial areas and brown spots were quantitatively analysed (Fig. 3). These two features showed significant improvement after IPL treatment (Fig. 4a, b, p < 0.01).

Improvement in PIE and PIH after IPL treatment. Statistical analysis shows an improvement in the red areas (a) and brown spots (b). The brown spots did not conform to a normal distribution and were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The red areas conformed to a normal distribution and were compared using paired t-test. **p < 0.01

Relapse and Side Effects

All patients tolerated IPL treatment-related pain well without topical anaesthetic agents. Adverse events were limited to transient erythema, dryness and itching at treatment sites, which resolved within 48 h in most patients. Acne relapsed in seven patients (11.7%) at the end of follow-up.

Discussion

In general, the GAIS and CADI values showed that IPL treatment significantly improved the overall facial appearance and the quality of life of patients with acne. The combined use of different cut-off filters targeted not only melanin and haemoglobin but also ‘rejuvenated’ the skin (restored skin elasticity, reduced wrinkles and shrank pores) by promoting collagen growth through photothermal and biochemical effects [14, 15]. The change in CADI values indicated an improved quality of life and positive impact of IPL treatment.

Since PIE is resistant to topical and oral drugs [16], energy-based devices are increasingly preferred by physicians and patients because of their effective performance, short downtime and fewer adverse effects. The 595 nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) is generally the first-line modality for treating superficial vascular skin lesions, such as telangiectasia, rosacea and port-wine stains. In a pilot study, Ho et al. reported clinical improvement of PIE, decreased lesion counts and enhanced skin elasticity following treatment with 595 nm PDL (fluence 9.5–11 J/cm2, pulse width 10 ms, spot size 7 mm, two sessions every 4 weeks) [5]. However, another split-face study that used almost similar parameters (fluence 8 J/cm2, pulse width 10 ms, spot size 7 mm, two sessions every 2 weeks) could not reproduce the positive clinical outcomes [17].

Fractional microneedling radiofrequency has also been evaluated for the treatment of PIE [18] given its anti-inflammatory effects and ability to cause dermal remodelling [5, 19]. Clinical improvement and consistent histological changes were attributed to controlled inflammation and modulated neovasculogenesis. Consistent with a previous report [20], we found decreased EAS and red areas recorded by the VISIA-CR system. IPL-induced vascular destruction is mainly caused by selective photothermolysis. As the targeted chromophores, the major absorption peaks of oxy-/deoxy-haemoglobin are 418 nm, 542 nm and 577 nm/555 nm. Thus, 560 nm and 590 nm are the most frequently used cut-off filters to deliver the wavelength around the absorption of haemoglobin to cause coagulation and thrombosis of dermal vessels.

PIH is more common than PIE in the darker FSTs (III–VI) owing to the activation/proliferation of melanocytes in response to stimulation by prostaglandins, leukotrienes and other inflammatory molecules [21, 22]. Acne-related overproduction of melanin and abnormal pigment deposition generally occurs in the epidermal tissue and may improve with time [23]. However, in several patients, acne-related PIH is characterised mainly by increased melanin deposition or melanophages in the dermis, which tends to persist for several years and may be permanent in some cases [24]. The reported energy-based devices (non-ablative fractional lasers and microneedling) treat PIH by increasing epidermal regeneration and decreasing pigmented cells [25, 26]. Notably, in darker FSTs, inappropriate treatment with these devices tends to cause or exacerbate PIH owing to irritation. While several studies have shown IPL to be an effective and safe modality for improving post-burn hyperpigmentation [27, 28], there is little evidence for its effects on acne-related PIH. The 560 nm cut-off filters are generally used for treating pigment disorders in Asian patients with significant improvement and low risk of PIH [29, 30]. Using digital photography and VISIA-CR system to count and analyse dark spots, we found significant improvement in acne-related pigment sequelae with IPL treatments. While the exact mechanism remains unclear, regulation of inflammation and cytotoxic effects on Propionibacterium acnes through selective photothermolysis have been proposed as potential underlying mechanisms [31, 32].

As mentioned previously, only those patients who presented with PIH and PIE for more than 6 months were recruited in our study. Before treatment, their lesions did not present self-relieving trends. Among the participants, only 6% received more than five IPL sessions. No serious IPL treatment-related side effects were reported. In our study, only 11.7% of patients experienced a relapse of acne at the end of the 6-month follow-up. Compared with the 5.6% relapse rate in participants who received oral isotretinoin therapy (period ranging from 1 to 12 months) [33], this long-term relapse prevention with IPL is acceptable because of the reduced downtime and very few side effects. Considering the above evidence, we suggest that IPL therapy should be considered as a strategy backed by sufficient scientific justification and risk–benefit analysis.Please confirm this change.Confirmed.

The major limitation of our study is its retrospective nature. Since PIH and PIE in a number of patients with acne could improve with time, comparison with a control group may increase the validity and reliability of the results. Further investigations involving a split-face design are needed to confirm the therapeutic efficacy of IPL.

Conclusion

For the first time, we reported the safety and effectiveness of IPL as a therapeutic option for both acne-related PIE and PIH. Furthermore, IPL prevents acne relapse for a longer period compared with other treatments.

References

Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, Hill K, Eaton SB, Brand-Miller J. Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(12):1584–90.

Chernyshov PV, Zouboulis CC, Tomas-Aragones L, Jemec GB, Manolache L, Tzellos T, et al. Quality of life measurement in acne. Position paper of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Forces on quality of life and patient oriented outcomes and acne, rosacea and hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(2):194–208.

Hosthota A, Bondade S, Basavaraja V. Impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and self-esteem. Cutis. 2016;98(2):121–4.

Davern J, O’Donnell AT. Stigma predicts health-related quality of life impairment, psychological distress, and somatic symptoms in acne sufferers. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0205009.

Yoon HJ, Lee DH, Kim SO, Park KC, Youn SW. Acne erythema improvement by long-pulsed 595-nm pulsed-dye laser treatment: a pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19(1):38–44.

Park KY, Ko EJ, Seo SJ, Hong CK. Comparison of fractional, nonablative, 1550-nm laser and 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of facial erythema resulting from acne: a split-face, evaluator-blinded, randomized pilot study. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16(3):120–3.

Abad-Casintahan F, Chow SK, Goh CL, Kubba R, Hayashi N, Noppakun N, et al. Frequency and characteristics of acne-related post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. J Dermatol. 2016;43(7):826–8.

Chen S, Wang Y, Ren J, Yue B, Lai G, Du J. Efficacy and safety of intense pulsed light in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris with a novel filter. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2019;21(6):323–7.

Deshpande AJ. Efficacy and safety evaluation of high-density intense pulsed light in the treatment of grades II and IV acne vulgaris as monotherapy in dark-skinned women of child bearing age. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(4):43–8.

Mokhtari F, Gholami M, Siadat AH, Jafari-Koshki T, Faghihi G, Nilforoushzadeh MA, et al. Efficacy of intense-pulsed light therapy with topical benzoyl peroxide 5% versus benzoyl peroxide 5% alone in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris: a randomized controlled trial. J Res Pharm Pract. 2017;6(4):199–205.

Fabi SG, Massaki A, Eimpunth S, Pogoda J, Goldman MP. Evaluation of microfocused ultrasound with visualization for lifting, tightening, and wrinkle reduction of the décolletage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6):965–71.

Walker N, Lewis-Jones MS. Quality of life and acne in Scottish adolescent schoolchildren: use of the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) and the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(1):45–50.

Karsai S, Schmitt L, Raulin C. The pulsed-dye laser as an adjuvant treatment modality in acne vulgaris: a randomized controlled single-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(2):395–401.

Cuerda-Galindo E, Díaz-Gil G, Palomar-Gallego MA, Linares-GarcíaValdecasas R. Intense pulsed light induces synthesis of dermal extracellular proteins in vitro. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(7):1931–9.

Faucz LL, Will SE, Rodrigues CJ, Hesse H, Moraes AC, Maria DA. Quantitative evaluation of collagen and elastic fibers after intense pulsed light treatment of mouse skin. Lasers Surg Med. 2018;50:644–50.

Harper JC. An update on the pathogenesis and management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(1 Suppl):S36–8.

Lekwuttikarn R, Tempark T, Chatproedprai S, Wananukul S. Randomized, controlled trial split-faced study of 595-nm pulsed dye laser in the treatment of acne vulgaris and acne erythema in adolescents and early adulthood. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(8):884–8.

Min S, Park SY, Yoon JY, Kwon HH, Suh DH. Fractional microneedling radiofrequency treatment for acne-related post-inflammatory erythema. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(1):87–91.

Lee SJ, Goo JW, Shin J, Chung WS, Kang JM, Kim YK, et al. Use of fractionated microneedle radiofrequency for the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris in 18 Korean patients. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(3):400–5.

Mathew ML, Karthik R, Mallikarjun M, Bhute S, Varghese A. Intense pulsed light therapy for acne-induced post-inflammatory erythema. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9(3):159–64.

Isedeh P, Kohli I, Al-Jamal M, Agbai ON, Chaffins M, Devpura S, et al. An in vivo model for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: an analysis of histological, spectroscopic, colorimetric and clinical traits. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(4):862–8.

Silpa-Archa N, Kohli I, Chaowattanapanit S, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a comprehensive overview: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and noninvasive assessment technique. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):591–605.

Elbuluk N, Grimes P, Chien A, Hamzavi I, Alexis A, Taylor S, et al. The pathogenesis and management of acne-induced post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(6):829–36.

Wang RF, Ko D, Friedman BJ, Lim HW, Mohammad TF. Disorders of Hyperpigmentation. Part I. Pathogenesis and clinical features of common pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;2(10):S0190-9622(22)00251-1.

Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(Suppl 3):91–7.

Bae YC, Rettig S, Weiss E, Bernstein L, Geronemus R. Treatment of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with darker skin types using a low energy 1927 nm non-ablative fractional laser: a retrospective photographic review analysis. Lasers Surg Med. 2020;52(1):7–12.

Siadat AH, Iraji F, Bahrami R, Nilfroushzadeh MA, Asilian A, Shariat S, et al. The comparison between modified Kligman formulation versus Kligman formulation and intense pulsed light in the treatment of the post-burn hyperpigmentation. Adv Biomed Res. 2016;5:125.

Li N, Han J, Hu D, Cheng J, Wang H, Wang Y, et al. Intense pulsed light is effective in treating postburn hyperpigmentation and telangiectasia in Chinese patients. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20(7–8):436–41.

Negishi K, Wakamatsu S, Kushikata N, Tezuka Y, Kotani Y, Shiba K. Full-face photorejuvenation of photodamaged skin by intense pulsed light with integrated contact cooling: initial experiences in Asian patients. Lasers Surg Med. 2002;30(4):298–305.

Kawada A, Shiraishi H, Asai M, Kameyama H, Sangen Y, Aragane Y, et al. Clinical improvement of solar lentigines and ephelides with an intense pulsed light source. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(6):504–8.

Hamilton FL, Car J, Lyons C, Car M, Layton A, Majeed A. Laser and other light therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris: systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(6):1273–85.

Bakus AD, Yaghmai D, Massa MC, Garden BC, Garden JM. Sustained benefit after treatment of acne vulgaris using only a novel combination of long-pulsed and Q-switched 1064-nm Nd: YAG lasers. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(11):1402–10.

Shahidullah M, Tham SN, Goh CL. Isotretinoin therapy in acne vulgaris: a 10-year retrospective study in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33(1):60–3.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant No. 81903201) and the medical‐engineering cross fund project of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Grant No. ZH2018QNA03). The study sponsor is also funding the journal’s Rapid Service Fees.

Author Contributions

Xianglei WU, Xue WANG, Xiujuan WU and Xiaoxi LIN designed the study, performed the research, analysed data, and wrote the paper. Qingqing CEN, Wenjing XI, Ying SHANG, Zhen ZHANG contributed to refining the ideas, carrying out additional analyses and finalizing this paper.

Disclosures

Xianglei WU, Xue WANG, Xiujuan WU, Qingqing CEN, Wenjing XI, Ying SHANG, Zhen ZHANG and Xiaoxi LIN have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All patients provided written, informed consent. All procedures were approved by Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital Ethics Committee. Procedures operated in this research were completed in keeping with the standards set out in the Announcement of Helsinki and laboratory guidelines of research in China.

Data Availability

The analysed data sets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Wang, X., Wu, X. et al. Intense Pulsed Light Therapy Improves Acne-Induced Post-inflammatory Erythema and Hyperpigmentation: A Retrospective Study in Chinese Patients. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 12, 1147–1156 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00719-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00719-9