Abstract

Introduction

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare, potentially life-threatening, neutrophilic, autoinflammatory skin disease characterised by recurrent flares of generalised sterile pustules and associated systemic features. Inconsistent diagnostic criteria and a lack of approved therapies pose serious challenges to GPP management. Our objectives were to discuss the challenges encountered in the care of patients with GPP and identify healthcare provider (HCP) educational needs and clinical practice gaps in GPP management.

Methods

On 24 July 2020, 13 dermatologists from 10 countries (Brazil, Canada, China, Egypt, France, Germany, Japan, Malaysia, the UK and the USA) attended a workshop to share experiences in managing patients with GPP. Educational needs and clinical practice gaps grouped according to healthcare system level were discussed and ranked using interactive polling.

Results

Lack of experience of GPP among HCPs was identified as an important individual HCP-level clinical practice gap. Limited understanding of the presentation and pathogenesis of GPP among non-specialists means misdiagnosis is common, delaying referral and treatment. In countries where patients may present to general practitioners or emergency department HCPs, GPP is often mistaken for an infection. Among dermatologists who can accurately diagnose GPP, limited knowledge of treatments may necessitate referral to a colleague with more experience in GPP. At the organisational level, important needs identified were educating emergency department HCPs to recognise GPP as an autoinflammatory disease and improving communication, cooperation and definitions of roles within multidisciplinary teams supporting patients with GPP. At the regulatory level, robust clinical trial data, clear and consistent treatment guidelines and approved therapies were identified as high priorities.

Conclusions

The educational imperative most consistently identified across the participating countries is for HCPs to understand that GPP can be life-threatening if appropriate treatment initiation is delayed, and to recognise when to refer patients to a colleague with more experience of GPP management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The rarity of GPP makes it impossible for all clinical centres to develop an adequate level of experience in the management of this disease. |

Thirteen practising dermatologists from 10 countries across five regions attended a virtual workshop to share experiences in managing patients with GPP and identify educational needs and clinical practice gaps. |

What was learned from the study? |

The most important educational imperative identified by the workshop participants was that both non-dermatologists and dermatologists should appreciate that GPP can be life-threatening if the initiation of correct treatment is delayed and understand when to refer patients with GPP to a specialist for diagnosis and/or treatment and ongoing management. |

Academic- and community-based practices that regularly care for patients with GPP should strive to learn from their experiences and collaborate with less experienced clinical centres to help ensure the delivery of consistent, best-practice treatment. |

Digital Features

This article is published with a Japanese translation, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21534162.

Introduction

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare, neutrophilic, autoinflammatory skin disease characterised by episodes (or flares) of widespread sterile, macroscopically visible pustules that can occur with or without systemic inflammation [1,2,3]. The reported prevalence of GPP varies widely, ranging from 1.76 per 1,000,000 persons in France to 7.46 per 1,000,000 persons in Japan and 5 per 10,000 persons in Germany [4,5,6]. Accurate estimates are difficult to obtain because of a historical lack of consistency in diagnosis and nomenclature. GPP is genetically, phenotypically and pathologically distinct from plaque psoriasis (psoriasis vulgaris) and can present differently among patients and across episodes within the same patient [3]. GPP flares may occur multiple times a year (relapsing disease) or may be more persistent and occur intermittently, with many years between episodes (persistent disease) [1,2,3].

Since its initial description by von Zumbusch in 1909, the pathogenesis of GPP has been poorly understood, leading to wide variation in the nomenclature, classification, diagnosis and treatment of the disease [1, 7]. Historically, GPP has been classified into different subtypes including acute GPP (von Zumbusch variant), pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (previous misnomer: impetigo herpetiformis) and infantile/juvenile pustular psoriasis [3, 8, 9]. Irrespective of subtype, GPP is associated with a considerable clinical burden, as symptoms and comorbidities can greatly affect patient quality of life [2, 3, 10, 11]. Furthermore, if left untreated, GPP may be life-threatening because of complications such as sepsis and multisystem organ failure [2, 4, 11, 12]. Several studies published at the beginning of this century have resulted in an improved understanding of GPP pathogenesis, highlighting the role of the interleukin (IL)-36 inflammatory pathway and mutations in the gene encoding the IL-36 receptor antagonist (IL36RN) [13,14,15,16,17].

The rarity of GPP means that management guidelines for the disease are widely based on strategies for managing plaque psoriasis, along with limited case studies and results of single-arm, open-label studies in GPP [2, 18, 19]. Recommended treatment generally includes systemic therapies, such as retinoids, methotrexate, cyclosporine and infliximab, as first-line agents. Biologic therapies are only approved specifically for the treatment of GPP in Japan, Taiwan and Thailand. Successful management of GPP flares requires rapid treatment with the most appropriate agent; however, lack of experience of GPP often means it is neither diagnosed promptly nor referred appropriately, resulting in treatment delays that can have a negative impact on response. There is a need for more widespread awareness of this debilitating disease.

Methods

On 24 July 2020, 13 practising dermatologists from 10 countries (Brazil, Canada, China, Egypt, France, Germany, Japan, Malaysia, the UK and the USA), the authors of this manuscript, attended a global virtual workshop, organised by Boehringer Ingelheim, to share personal experiences of the diagnosis, treatment and management of patients with GPP. The workshop participants practise in a wide range of settings, including private and public clinics as well as university departments and government hospitals, with annual experience in the management of GPP ranging from 1 patient per year to more than 50 patients per year (median 5 patients per year), including treatment of patients with single and/or multiple recurring GPP flares.

The overarching aims of the workshop were to review the current real-world standards of care in GPP (and variation between countries) and to identify healthcare provider (HCP) educational needs and clinical practice gaps in GPP management. Specific topics discussed were based on a web-based questionnaire that was completed prior to the meeting. In this questionnaire, we provided our thoughts on the key challenges in the clinical management of patients with GPP in our respective regions. Specific questions included in the questionnaire were agreed upon by the sponsor in consultation with the meeting chairs, Bruce Strober and Yukari Okubo. We considered clinical practice gaps at three different levels: macro (system) level, meso (organisational/institutional) level and micro (individual HCP) level. During the workshop, key challenges and barriers to GPP management identified in the questionnaire were discussed and ranked using an interactive online voting system. This article provides an overview of the main discussion topics during the workshop and details the educational needs and clinical practice gaps that were identified on the basis of our personal opinions and experiences of GPP diagnosis and treatment.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies as well as personal experience and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Standards of Care in GPP: Perspectives and Challenges

Key perspectives and challenges identified from the pre-meeting questionnaire and discussed in the workshop are summarised in Table 1.

Diagnosis

Timely GPP diagnosis is critical to ensure prompt and appropriate treatment. Among the workshop participants, there was a consensus that GPP diagnosis can be difficult, with 75% (9/12) of those who responded reporting it to be “challenging” or “sometimes challenging”. While the diagnosis itself may not be challenging for an experienced dermatologist, non-dermatologists frequently misdiagnose GPP as a periodic fever syndrome or an infection, and initiate treatment with systemic corticosteroids or systemic antimicrobials, respectively, rather than immediately referring the patient to a dermatologist. This is a particular problem when patients initially present to a general practitioner or a hospital emergency department HCP, as this can result in critical delays in initiating the correct treatment. On the basis of our experience, misdiagnosis may be less common in countries where patients are more likely to present directly to a dermatologist, such as Brazil, Egypt, Germany, China and Japan.

We agreed that the key challenges to a prompt GPP diagnosis are the heterogeneous clinical presentation (in terms of history of plaque psoriasis, age of onset, severity and natural history) as well as differential diagnosis from other conditions with predominantly neutrophilic inflammation, particularly acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). A detailed medical history can help differentiate between GPP and AGEP; for example, 90% of AGEP cases are associated with certain medications, such as systemic antimicrobials, whereas GPP may be suspected in patients who have a history of plaque psoriasis and quick tapering of a systemic treatment, such as corticosteroids or a tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) inhibitor [20,21,22]. The clinical course of the disease may also provide clues because AGEP has a more abrupt onset than GPP and generally resolves much more quickly than GPP.

Historically, the nomenclature and classification of GPP have varied widely [1]. More recently, accumulating clinical experience and improvements in the understanding of GPP pathogenesis have led to the development and publication of standardised diagnostic criteria for GPP by the Japanese Dermatological Association (JDA) and the European Rare and Severe Psoriasis Expert Network (ERASPEN) (Table 2) [1, 2]. We felt that both these definitions are associated with some limitations. The JDA definition fails to consider the presence or absence of psoriatic plaques, whereas the ERASPEN definition lacks inclusion of characteristic histopathological findings and the clinical finding of lakes of pus, both very typical features of GPP. Nevertheless, these published criteria may help to clarify ambiguous textbook descriptions of GPP that could be confusing for less experienced dermatologists; for example, the ERASPEN definition excludes cases in which pustulation is restricted to psoriatic plaques, which are often included in textbook descriptions.

Treatment

One of the most challenging aspects of GPP treatment identified during the workshop is the rapid decision-making needed to ensure that the cutaneous and systemic symptoms of the disease are controlled. In addition to the diagnostic challenges, other conditions must be excluded before treatment can be initiated (e.g. tuberculosis and malignancy), meaning that patients are unlikely to receive the most appropriate treatment within 48 h of symptom onset. Physicians may also be unaware of new treatment innovations, resulting in further delays. Another major challenge is the lack of GPP-specific therapy approved in most countries. At the time of writing, biologic therapies for GPP have only been approved in Japan, Taiwan and Thailand, on the basis of small, single-arm clinical trials. Standard treatment guidelines are also lacking.

Consistent with the published literature, the treatments that we use most widely for GPP are retinoids, methotrexate and cyclosporine [2, 9, 13]. Cyclosporine is often used to treat GPP in pregnant women, if no other treatment is available, because it has previously been well tolerated in pregnant women who were renal transplant recipients, and is not likely to be teratogenic [2]. Corticosteroids should be used with caution during pregnancy because of concerns that inappropriate tapering may induce a GPP flare [2, 9].

We also discussed comorbidities as a key challenge in GPP treatment because most therapeutic options are associated with several potential toxicities and contraindications [2]. For example, careful consideration must be given to the pros and cons of methotrexate in patients with liver abnormalities and in women of childbearing potential.

We found that our expectations of treatment responses vary depending on what therapy is used and we agreed that expectations should be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, acitretin can help to control fever and clear pustules within a few days or up to a week, whereas responses to methotrexate generally take longer. Some workshop participants suggested that if responses to acitretin have not been observed within a week, physicians may be hesitant to increase the treatment dose because of concerns relating to adverse events and decreased tolerability. If a patient receiving cyclosporine has not obtained a response within 3–6 months, treatment is generally switched to an alternative systemic therapy.

Dermatologists from Japan noted that GPP management has improved with the availability of biologic therapies. Several biologics approved in Japan can be used in GPP treatment, including monoclonal antibodies against TNFα (adalimumab, infliximab and certolizumab pegol) [2, 23]; IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab and brodalumab) [2]; and IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab and risankizumab) [24, 25]. In countries where biologics are not approved specifically for GPP treatment, their use is more limited. In some countries, biologics are not widely used because of their prohibitive cost. Specific regulatory approval is usually a prerequisite for coverage by insurance companies, and even with approval, there is often a requirement that patients have failed or are intolerant to other systemic therapies before they can access biologics. Thus, even in countries where biologics are available, the requirement for the patient to bear the cost is a major barrier to their early use. The need for long-term treatment of GPP can also present further financial challenges to patients. It should be noted that the costs associated with inadequate initial disease control (including but not limited to financial impact of work and school absenteeism; repeated visits to outpatient clinics and emergency departments; and multiple hospital admissions) may prove to be greater than the cost of more effective (albeit more expensive) treatments from the outset.

Ongoing Management

We agreed that the follow-up of patients receiving GPP treatment is hampered by a lack of validated assessment tools for monitoring treatment response, with most tools unable to capture the rapid day-to-day changes inherent to the dynamic nature of GPP. Development of a scoring system that can guide evaluation of the area and severity of the pustules, oedema and erythema observed in patients with GPP would help physicians assess disease severity and determine whether systemic treatment and hospitalisation are required [26]. The aim of long-term GPP management is also to delay or prevent further flares. Although some treatments can help with this, it is important to understand the role of patients themselves in avoiding potential triggers. Patient expectations may need to be established after careful monitoring over time. A cohesive multidisciplinary team might be important for addressing the wider needs of the patient and their family, such as appropriate psychological follow-up and genetic counselling. The psychological burden that GPP places on patients, both in terms of the challenges of treatment non-response and the financial pressures associated with funding long-term treatment, is considerable. In addition, children with GPP require specific specialist support.

Clinical Practice Gaps and Educational Needs

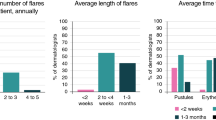

Having discussed the challenges and barriers to effective GPP management, we considered the importance of addressing specific clinical practice gaps and educational needs to ultimately improve outcomes for patients with GPP. These gaps and needs were grouped according to healthcare system levels: at the “macro” level, regulatory-, economic- and system-level factors; at the “meso” level, organisational or hospital-level factors; and at the “micro” level, individual HCP-level factors. During the workshop, we voted on which of the gaps presented important challenges to GPP management in our respective regions (Fig. 1).

Key clinical practice gaps and educational needs identified by workshop participants as important in their country: regulatory-, economic- and system-level factors (a); organisational or hospital-level factors (b); and individual HCP-level factors (c). The clinical practice gaps/educational needs were based on information provided in the pre-meeting questionnaire. During the virtual meeting, the participating dermatologists were asked to indicate which three clinical practice gaps/educational needs in each group were most important in their country. The bars show how many dermatologists selected each clinical practice gap/educational need. GPP generalized pustular psoriasis, HCP healthcare provider

Regulatory-, Economic- and System-Level Factors (“Macro” Level)

At the regulatory level, a lack of robust clinical trial data was most frequently identified as an important clinical practice gap, followed by a lack of treatment guidelines and a lack of approved treatments (although the latter did not apply to Japan; Fig. 1a). Key elements of management that warrant further guidance include clear first- and second-line treatment options for GPP; treatment during GPP flare recurrence and “rescue” treatments for GPP; management of GPP and comorbidities; and rehabilitation for patients with GPP. The safety and efficacy of treatments for GPP are based on limited data because the rarity of the disease makes it difficult to recruit sufficient patient numbers for large randomised controlled trials. Furthermore, the spontaneously self-limiting episodic pattern of GPP complicates efficacy assessments for new interventions in this population. While numerous published case reports and case series are cited in available guidelines and reviews [2, 9, 18, 27], these data are potentially biased, as negative case results are rarely submitted for publication. A lack of robust data makes it difficult to construct clear GPP management guidelines with strong recommendations, and in many countries, treatment for GPP still follows existing guidelines for plaque psoriasis. In the USA, treatment recommendations for pustular psoriasis were published in 2012 and have not yet been updated to include new biologic therapies that have become available [8, 18]. More recently updated (2018) GPP-specific guidelines are available in Japan [2]. While these provide a framework for physicians to use in clinical practice, they are not intended as definitive recommendations because of the aforementioned data limitations. Because evidence-based recommendations are lacking, physicians are reliant on anecdotal approaches formed from their own clinical experience of different treatments. Experience with certain treatments varies considerably between countries, so the development of a one-size-fits-all treatment guideline is not possible on the basis of the clinical data that are currently available. The Japanese guidelines are not appropriate for use in other countries because the availability and funding of treatments vary widely, and the nature of GPP in Japan cannot be generalised to the rest of the world. A lack of specific approved therapies was identified as an important clinical practice gap by five of the workshop participants from countries where there are no approved therapies. A quarter of the workshop participants indicated that funding and access to therapies was an issue.

Organisational- or Hospital-Level Factors (“Meso” Level)

At an organisational level, the clinical practice gap most frequently identified as important was the need to educate emergency department HCPs to recognise GPP as an autoinflammatory disease rather than an infection (Fig. 1b). In countries where it is not easy to visit a dermatologist directly (e.g. Canada and Malaysia), patients may be more inclined to bypass their primary care physician by going directly to a hospital emergency department; however, misdiagnosis is a common issue when patients with GPP visit emergency departments. GPP symptoms are often construed and treated as an infection, rather than an autoinflammatory disease, resulting in emergency department HCPs often prescribing inappropriate treatments. As a result, patients usually make several visits to the emergency department before being referred to the right specialist.

Another important organisational-level clinical practice gap identified in the workshop was the need to enhance communication and patient transfer within and between centres managing patients with GPP throughout treatment and rehabilitation. Defining clear roles and responsibilities within the multidisciplinary team involved in GPP management, including allocation of a primary point of contact for patients, was agreed to be of great importance. Several stakeholders may be involved in the management of patients with GPP, including those working in dermatology, rheumatology, genetics, cardiology and high-dependency/intensive care units. In some cases, specialists in dietetics may be involved in long-term patient management, helping to optimise the chance of treatment success in frail patients. While it is important to include all these specialities when creating an informed management plan for each patient, working within a multidisciplinary team can present its own challenges. As an example, for paediatric patients with GPP, some dermatologists would look to prescribe systemic anti-inflammatory treatments but may be challenged by other physicians who feel that this is inappropriate for patients of such a young age.

A further organisational-level clinical practice gap related to treatment is the need for more streamlined processes for authorisation and insurance approval of certain treatments, particularly biologics.

Individual HCP-Level Factors (“Micro” Level)

At the individual level, the key educational and clinical practice GPP management gaps identified mostly concerned diagnosis and initial treatment. Lack of experience of GPP among both non-dermatologists and dermatologists was identified as an important gap at the individual level (Fig. 1c). In some countries, patients with GPP may visit their primary care physician after symptom onset because direct access to dermatologists is not possible (e.g. Canada and Malaysia). This can result in misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment. Although there is no expectation for primary care physicians to correctly identify GPP, it is important that they understand the need to refer patients with suspected GPP as soon as possible so they can be treated quickly and appropriately. In contrast, in many countries (e.g. Brazil, Egypt, Germany, Japan and the USA), there is not a culture of visiting a primary care physician after GPP symptom onset; rather, patients with GPP symptoms visit their dermatologist directly. While it might seem obvious for non-dermatologists to refer suspected cases of GPP to a dermatologist to ensure accurate diagnosis, it is equally important for dermatologists to refer patients to a colleague if they feel unsure or uncomfortable with treating GPP. Less experienced dermatologists, who are likely to have seen textbook descriptions of GPP, may only encounter a handful of patients with GPP over the course of their career. Moreover, these patients are often referred to or managed by more experienced dermatologists, so the opportunity of less experienced dermatologists to follow patients over the course of diagnosis, treatment and follow-up is limited. The key challenges in this case are the lack of awareness of the latest treatments and how they should be used. The important educational imperative is that both non-dermatologists and dermatologists appreciate that GPP can be life-threatening if the initiation of correct treatment is delayed, and that they understand when to refer patients to a specialist.

A need to enhance patient–physician relationships was also suggested as a key clinical practice gap. The psychological burden that GPP places on patients is substantial, and consistent long-term follow-up and support are important. Patients also need to actively engage in their own post-flare management by adhering to maintenance therapy and avoiding potential triggers of GPP. It is therefore important to educate patients on their role in ongoing GPP management and flare avoidance.

Conclusions

The rarity of GPP makes it impossible for all clinical centres to develop an adequate level of experience in the management of the disease. The most important educational imperative is that both non-dermatologists and dermatologists appreciate that GPP can be life-threatening if the initiation of correct treatment is delayed, and that they understand when to refer patients to a specialist for diagnosis and/or treatment and ongoing management. HCPs in academic- and community-based practices that provide care for multiple patients with GPP should strive to efficiently learn from their experiences and to further develop their capabilities in the field of GPP diagnosis and treatment. Such specialist centres could then collaborate with other centres to ensure delivery of consistent, best-practice treatment for patients with GPP.

Change history

07 December 2022

“A Japanese translation was retrospectively added to this publication.”.

References

Navarini AA, Burden AD, Capon F, et al. European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1792–9.

Fujita H, Terui T, Hayama K, et al. Japanese guidelines for the management and treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis: the new pathogenesis and treatment of GPP. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1235–70.

Bachelez H. Pustular psoriasis: the dawn of a new era. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00034.

Augey F, Renaudier P, Nicolas JF. Generalized pustular psoriasis (Zumbusch): a French epidemiological survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:669–73.

Schäfer I, Rustenbach SJ, Radtke M, Augustin J, Glaeske G, Augustin M. Epidemiology of psoriasis in Germany–analysis of secondary health insurance data. Gesundheitswesen. 2011;73:308–13.

Ohkawara A, Yasuda H, Kobayashi H, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in Japan: two distinct groups formed by differences in symptoms and genetic background. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:68–71.

von Zumbusch LR. Psoriasis und pustulöses exanthem. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1909;99:335–46.

Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, Mansouri B. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:131–44.

Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:907–19.

Golembesky AK, Kotowsky N, Gao R, Yamazaki H. PRO16 Healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) in Japan: a claims database study. Value Health Reg Issues. 2020;22:S98.

Choon SE, Lai NM, Mohammad NA, Nanu NM, Tey KE, Chew SF. Clinical profile, morbidity, and outcome of adult-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: analysis of 102 cases seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:676–84.

Borges-Costa J, Silva R, Gonçalves L, Filipe P, Soares de Almeida L, Marques Gomes M. Clinical and laboratory features in acute generalized pustular psoriasis: a retrospective study of 34 patients. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:271–6.

Boehner A, Navarini AA, Eyerich K. Generalized pustular psoriasis—a model disease for specific targeted immunotherapy, systematic review. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:1067–77.

Furue K, Ulzii D, Tanaka Y, et al. Pathogenic implication of epidermal scratch injury in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2020;47:979–88.

Akiyama M, Takeichi T, McGrath JA, Sugiura K. Autoinflammatory keratinization diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1545–7.

Akiyama M, Takeichi T, McGrath JA, Sugiura K. Autoinflammatory keratinization diseases: an emerging concept encompassing various inflammatory keratinization disorders of the skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;90:105–11.

Neuhauser R, Eyerich K, Boehner A. Generalized pustular psoriasis—dawn of a new era in targeted immunotherapy. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:1088–96.

Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279–88.

Umezawa Y, Ozawa A, Kawasima T, et al. Therapeutic guidelines for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) based on a proposed classification of disease severity. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295(Suppl 1):S43–54.

Crowley JJ, Pariser DM, Yamauchi PS. A brief guide to pustular psoriasis for primary care providers. Postgrad Med. 2021;133:330–44.

Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

Kardaun SH, Kuiper H, Fidler V, Jonkman MF. The histopathological spectrum of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) and its differentiation from generalized pustular psoriasis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1220–9.

UCB. CIMZIA® (certolizumab pegol) now available for patients in Japan living with multiple psoriatic diseases. 2020. https://www.ucb.com/stories-media/Press-Releases/article/CIMZIA-certolizumab-pegol-now-Available-for-Patients-in-Japan-living-with-Multiple-Psoriatic-Diseases. Accessed 21 Jan 2021.

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Report on the deliberation of results. Tremfya subcutaneous injection 100 mg syringe (guselkumab). 2018. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000234741.pdf. Accessed Dec 2020.

Abbvie. AbbVie announces first regulatory approval of SKYRIZI™ (risankizumab) for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, generalized pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in Japan. 2019. https://news.abbvie.com/news/abbvie-announces-first-regulatory-approval-skyrizi-risankizumab-for-treatment-plaque-psoriasis-generalized-pustular-psoriasis-and-erythrodermic-psoriasis-and-psoriatic-arthritis-in-japan.htm. Accessed 21 Jan 2021.

Stephenson C, Prajapati VH, Hunter C, Miettunen P. Novel use of Autoinflammatory Diseases Activity Index (AIDAI) captures skin and extracutaneous features to help manage pediatric DITRA: a case report and a proposal for a modified disease activity index in autoinflammatory keratinization disorders. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:670–6.

Wang WM, Jin HZ. Biologics in the treatment of pustular psoriasis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19:969–80.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The workshop described in this manuscript was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. Ogilvy Health (London, UK) assisted with the organisation of the virtual workshop, funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. The authors did not receive payment related to the development of the manuscript. Agreements between Boehringer Ingelheim and the authors included the confidentiality of the study data. Boehringer Ingelheim funded the journal’s Rapid Service fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

In the preparation of this manuscript, Esther Race and Leigh Church, PhD, of OPEN Health Communications (London, UK) provided medical writing, editorial and/or formatting support, which was contracted and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Author Contributions

All authors (Bruce Strober, Joyce Leman, Maja Mockenhaupt, Juliana Nakano de Melo, Ahmed Nassar, Vimal H. Prajapati, Paolo Romanelli, Julien Seneschal, Athanasios Tsianakas, Lee Yoong Wei, Masahito Yasuda, Ning Yu, Ana C. Hernandez Daly, and Yukari Okubo) equally contributed to the concept, design and drafting of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies as well as personal experience, and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

To ensure independent interpretation of clinical study results, Boehringer Ingelheim grants all external authors access to all relevant material, including participant-level clinical study data, and relevant material as needed by them to fulfil their role and obligations as authors under the ICMJE criteria. Furthermore, clinical study documents (e.g. study report, study protocol, statistical analysis plan) and participant clinical study data are available to be shared after publication of the primary manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal and if regulatory activities are complete and other criteria met per the BI Policy on Transparency and Publication of Clinical Study Data: https://vivli.org/ Prior to providing access, documents will be examined, and, if necessary, redacted and the data will be de-identified, to protect the personal data of study participants and personnel, and to respect the boundaries of the informed consent of the study participants. Clinical Study Reports and Related Clinical Documents can also be requested via the link https://vivli.org/. All requests will be governed by a Document Sharing Agreement. Bona fide, qualified scientific and medical researchers may request access to de-identified, analysable participant clinical study data with corresponding documentation describing the structure and content of the datasets. Upon approval, and governed by a Data Sharing Agreement, data are shared in a secured data-access system for a limited period of 1 year, which may be extended upon request. Researchers should use https://vivli.org/ link to request access to study data and https://www.mystudywindow.com/msw/datasharing for further information.

Disclosures

Bruce Strober has served as a consultant (honoraria) for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Arena, Aristea, Asana, Boehringer Ingelheim, Immunic Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Connect Biopharma, Dermavant, Equillium, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly, Maruho, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera, Novartis, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, UCB Pharma, Sun Pharma, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme and Ventyxbio; a speaker for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen and Sanofi Genzyme; co-Scientific Director (consulting fee) for CorEvitas (Corrona) Psoriasis Registry; an investigator for Dermavant, AbbVie, Corrona Psoriasis Registry, Dermira, Cara Therapeutics and Novartis; and Editor-in-Chief (honorarium) for the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Joyce Leman declares part-time employment as a scientific fellow in biodermatology with LEO Pharma, and receipt of consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH for the GPP advisory board. Maja Mockenhaupt declares grants related to specific analyses of cutaneous adverse reactions via contracts between the university (for the research unit “dZh-RegiSCAR”) and Tibotec-Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Pharma, Sanofi-Aventis and Janssen; cutaneous adverse reactions consulting fees from Merck and Pfizer; payment of honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Vivantes Clinics Berlin, DERFO Essen, Forum Derma Mannheim, Interdisziplinäre Fobi Dresden, SIMID Verona, Galderma Symposium Stockholm, Derma Fobi Freiburg, and Medicademy course Copenhagen; and payment for an expert testimony in a court case of a severe cutaneous adverse reaction. Ahmed Nassar has served as an investigator for Sanofi and Boehringer Ingelheim, as well as receiving consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH for the GPP advisory board. Vimal H. Prajapati has served as an investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, AnaptysBio, Arcutis, Arena, Asana, Bausch Health, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, Cor-Evitas (Corrona), Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Nimbus Lakshmi, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, UCB Pharma and Valeant; and an advisor, consultant and/or speaker for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Aralez, Arcutis, Aspen, Bausch Health, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Cipher, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Homeocan, Janssen, LEO Pharma, L'Oreal, Medexus, Novartis, Pediapharm, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, Sun Pharma, Tribute, UCB Pharma and Valeant. Lee Yoong Wei has received consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH for the GPP advisory board, and honoraria for presentations from AbbVie. Masahito Yasuda is a clinical study investigator for Eli Lilly. Ana C. Hernandez Daly is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. Yukari Okubo declares grants or contracts from Eisai, Maruho and Shiseido Torii; consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharma, JIMRO, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Novartis Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, Taiho, Tanabe-Mitsubishi, Torii and UCB Pharma; honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharma, JIMRO, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Novartis Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, Taiho, Tanabe-Mitsubishi, Torii and UCB Pharma. Juliana Nakano de Melo, Paolo Romanelli, Julien Seneschal, Athanasios Tsianakas and Ning Yu have nothing to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Strober, B., Leman, J., Mockenhaupt, M. et al. Unmet Educational Needs and Clinical Practice Gaps in the Management of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis: Global Perspectives from the Front Line. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 12, 381–393 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00661-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00661-2