Abstract

Introduction

Relapse is common after treatment discontinuation for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. The objective of this study was to understand the remission duration and long-term outcomes in psoriasis patients after biologic withdrawal.

Methods

We retrospectively included the follow-up data of 184 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis after the end of 11 biologic or tofacitinib trials conducted between 2004 and 2016.

Results

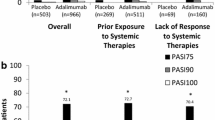

Among the 232 treatment courses, 95 achieved (psoriasis area and severity index) PASI 75 at the end of the studies. At 6 months after treatment discontinuation, the systemic treatment-free rates of our patients who entered the PRESTA, PRISTINE, PEARL, ERASURE, CLEAR, the global tofacitinib study, and the IXORA-P study were 66.7%, 66.7%, 75.0%, 16.7%, 22.2%, 33.3%, and 29.2%, respectively. Pooled data showed a serious adverse event incidence rate of 1.5/100 person-years. The proportions of systemic treatment-free episodes were 16.8%, 7.4%, 4.3%, 3.2%, and 3.2% at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years, respectively. Biologics were reinitiated in 41.9%, 66.7%, 77.1%, 83.5%, and 86.1% at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years, respectively. Multivariate generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression analysis demonstrated that predictors for a longer relapse-free duration were baseline PASI, PASI improvement, biologic naivety, and early biologic intervention. Patients who received early biologic intervention, who achieved PASI 90, and who were biologic naive showed significantly higher relapse-free rate by Kaplan–Meier analysis with log rank test.

Conclusions

Systemic treatment was required in 86.1% of patients within 12 months after biologic withdrawal and biologics were reinitiated in 77.1% of patients after 3 years. However, early biologic administration within 2 years after diagnosis demonstrated a lower risk of relapse in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common chronic immune-mediated disease [1] which impairs patients’ quality of life significantly [2, 3]. The treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis used to be difficult [4], but improved understanding of the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis has led to the development of highly effective targeted therapies, mainly biologics, in the last decade [5]. Currently, reductions in the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) of 75% or even 90% are expected in the majority of patients since the introduction of anti-IL17 drugs [6].

Biologic therapy is mainly used in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and often in those who failed phototherapy and systemic therapy. Most patients meeting the criteria in clinical trials had a disease history of more than 10 years [7, 8], and usually experience disease relapse after treatment discontinuation. Nevertheless, hypotheses have been proposed that early treatment may result in better clinical control and even alter the natural course of the disease in the long term [9,10,11].

Long-term treatment is recommended for patients with psoriasis because of its chronic relapsing nature. Yet, treatment duration in clinical trials of biologics varies between 3 months and at most 5 years, and drug discontinuation is inevitable after the end of the trials. In real-world practice, treatment interruption is also common, mainly because of loss of efficacy [12]. Thus, it is important to understand the remission duration and long-term outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated by biologics after treatment discontinuation.

In our study, we evaluated clinical relapse in biologics and tofacitinib responders with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who discontinued trial drugs. Clinical features predictive of long-term remission were analyzed and long-term severe adverse events were collected.

Methods

We retrospectively included 184 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who participated in 11 biologic or tofacitinib clinical studies conducted between 2004 and 2016 in our clinic (Table 1). Medications prescribed included efalizumab [13], alefacept [14], etanercept [15, 16], ustekinumab [17], secukinumab [18, 19], tofacitinib [20, 21], ixekizumab [22], and guselkumab [23] (in time sequence). During safety follow-up periods of the trials, subjects were free from concomitant systemic therapy per protocols. All treatments were given as monotherapy, yet 37 patients took part in multiple trials; therefore, 232 courses of therapies were given. Participants were at least 20 years old with a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis which involved at least 10% body surface area (BSA) at baseline with PASI at least 10 or 12 according to protocols.

Subjects from 11 studies were evaluated separately and also pooled to evaluate time to relapse and outcome. Clinical relapse of psoriasis was defined as the 5-item scale Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) ≥ 2, or initiation of oral systemic anti-psoriasis agents (methotrexate, acitretin, and cyclosporine), phototherapy, or biological therapy after achieving at least 75% reduction in PASI (PASI 75) compared to baseline. In our clinical practice, patients with unstable courses, occurrence of many newly onset lesions, extensive plaques, significantly impaired quality of life, or pruritic plaques resistant to topical treatment were given systemic treatment. Relapse-free duration was defined as the period between relapse and the last administration of investigational agent. Biologics were given when patients met the inclusion criteria of further trials or the reimbursement guideline set by the national health insurance. The latter was PASI and BSA at least 10 in patients who had failed, were intolerant, or contraindicated to two out of three conventional systemic agents (methotrexate, acitretin, and cyclosporine) and phototherapy, each for 12 weeks. Long-term outcome was evaluated on the basis of medical records and patient interviews, and was collected during the trial follow-up periods and also after the trials. Special attention was paid for new-onset inflammatory joint pain suggestive of psoriatic arthritis and erythroderma (BSA ≥ 75%) which developed after discontinuation of investigational agents. Patients who missed office appointments were contacted by telephone. In accordance with the 1996 Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, ethical approvals were obtained from the National Taiwan University Research Ethics Committee for all trials.

Statistical Analysis

To compare intergroup discrepancy, Student’s t test and the Wilcoxon test were used for continuous variables and the Fisher’s exact or Chi-square tests were applied for discrete variables. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) was implemented to estimate predictors of duration to relapse after withdrawal of biologics. GEE methodology has taken into consideration for multiple treatment courses of the same patient. Confounding factors including age, sex, body weight, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) were taken into account in the GEE analysis. Survival analysis was executed to evaluate the proportions of relapse-free subjects. Kaplan–Meier analysis with log rank test (Mantel–Cox test) was performed to assess the difference between early and delayed biologic intervention, patients who achieved PASI 90 and those who only achieved PASI 75, and biologic-naive and biologic-experienced patients. Two-tailed tests were conducted and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were carried out using SPSS version 25.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical outcomes are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Mean follow-up duration was 83 months, while the median duration was 4.7 years (range 0.1–14.4). Among patients without a previous history of arthritis, 40 patients developed arthralgia/arthritis after discontinuation of biologics in a total of 1432.2 person-years (PY) of follow-up. Pooled data showed an incidence rate of 2.8/100 PY. PsA was most commonly observed in patients who discontinued efalizumab (n = 12), but intergroup differences were not significant. On the contrary, newly developed arthritis was not documented in the NAVIGATE protocol. The incidence rate of erythrodermic psoriasis varied, with the highest one observed in the ERASURE study (7.4/100 PY). No patients experienced erythroderma after the PRESTA study. Generalized pustular psoriasis was observed in one subject who was injected with secukinumab during the entire follow-up period of this pooled analysis.

Serious adverse events (SAE), as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization, developed in 21 subjects during a median follow-up of 60.5 months. The incidence rate of SAE was 1.5 per 100 PY. The most common SAE was cerebral vascular event (n = 7), followed by death (n = 5). Causes of death included two cardiac arrests, two heart failures, and one pancreatic cancer. Malignancy accounted for four cases, specifically two nasopharyngeal cancers, one colon cancer, and one parotid cancer. Other issues were acute retinal necrosis (n = 2), chronic kidney disease (n = 2), and coronary artery disease. Among different studies, SAE were observed in most trials except the tofacitinib in Asian, the IXORA-P, and the NAVIGATE study.

Of the 232 treatment courses screened for eligibility, a total of 95 treatment courses achieved PASI 75 at the end of each study. Median time to relapse was 7.6 months. Regarding the relapse-free rate for each study, all of the PASI 75 responders who received efalizumab (4/25), alefacept (1/14), the Asian tofacitinib trial (NCT01815424) (5/14), and guselkumab (n = 10/14) relapsed within 5 months. At 6 months after treatment discontinuation, the relapse-free rates of our patients who entered the PRESTA, PRISTINE, PEARL, ERASURE, CLEAR, the global tofacitinib study (NCT01815424), and the IXORA-P study were 66.7%, 66.7%, 75.0%, 16.7%, 22.2%, 33.3%, and 29.2%, respectively. At 12 months, the proportions were 50%, 33.3%, 33.3%, 11.1%, 0, 16.7%, and 16.7%, respectively. In total, the proportions of relapse-free treatment episodes were 16.8% (16/95) at 1 year, 7.4% (7/94) at 2 years, 4.3% (4/93) at 3 years, 3.2% (3/93) at 4 years, and 3.2% (3/93) at 5 years. Biologics were reinitiated in 41.9% (39/93) at 1 year, 66.7% (62/93) at 2 years, 77.1% (64/83) at 3 years, 83.5% (66/79) at 4 years, and 86.1% (68/79) at 5 years after the end of the trials.

Predictors for remission duration were estimated with 95 treatment courses in patients who had achieved PASI 75 at the end of the trials (Table 3). After correction of the covariates including age, sex, body weight and PsA at baseline, multivariate GEE regression analysis demonstrated that predictors for a longer relapse-free duration after biologic cessation were baseline PASI [95% confidence interval (CI) − 0.226, − 0.074; p < 0.001), PASI improvement during treatment (95% CI 0.062, 0.204; p < 0.001), biologic naivety (95% CI 0.213, 1.007; p < 0.001), and early biologic intervention (95% CI 0.457, 1.046; p = 0.003).

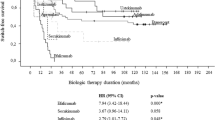

A total of 95 (40.9%) treatment episodes reached PASI 75 at the end of the trials. Patients were further grouped by the duration between the diagnosis of psoriasis and the initiation of the trial drugs, PASI improvement at the end of the studies, and status of previous biological treatment experience (Table 4). Patients who received early biologic intervention within 2 years of diagnosis showed significantly higher relapse-free rates by Kaplan–Meier analysis with log rank test (p = 0.002) (Fig. 1). The median time to relapse for early and delayed biologic intervention was 15 and 27 weeks. At 6, 12, and 24 months, the cumulative relapse-free rates for early versus delayed administration of biologic group were 51.5% versus 22.6%, 33.3% versus 8.1% and 15.2% versus 4.8%, respectively.

Relapse-free rates after discontinuing biologics. Survival functions derive from Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrated the difference in relapse interval after biologics cessation. Stratified survival curves demonstrated significant longer relapse-free duration of biologic naivety (p < 0.001), early-biologic intervention (p = 0.002) and patients reaching PASI 90 at end of trials (p = 0.006). PASI psoriasis area and severity index

The treatment courses in patients who were biologic naive demonstrated a smaller proportion of relapse by survival analysis when compared with those who experienced biologics (p < 0.001). Lower relapse rate was also observed in patients who achieved PASI 90 when compared to those achieved PASI 75 (p = 0.006) (Fig. 1). The patients who reached a PASI 90 at the end of the trial had a similar median time to relapse of 5.5 months as those who were biologic naive irrespective of PASI at the end of the trial. Subjects who reached PASI 90 showed a higher relapse-free rate compared to those who only achieved PASI 75 at 6 months (46.8% cf. 18.7%) and 1 year (21.3% and 12.5%). Those who were never exposed to biologics also demonstrated better relapse-free rate compared to those who failed previous biologics at 6 months (25% cf. 23.3%) and 1 year (11.4% and 5.7%).

Discussion

The goal of anti-psoriatic treatments has been revised in the light of modern targeted immune therapies which showed dramatic efficacy [5]. The efficacy expectation has evolved beyond greater PASI reduction to include faster onset, better drug sustainability, longer remission duration, and recapture of efficacy after reinitiation. Despite the advance in treatment, some questions remain underexplored, such as the possibility of disease modification or predictors for long-term remission. Long-term outcomes after treatment discontinuation were also poorly studied. In controlled studies, patients were typically followed up for 2 weeks [21, 24] to 12 weeks [23] after the end of study for safety reasons. Therefore, there is a lack of knowledge about remission duration and long-term outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who discontinued biologic treatments.

Before the era of biological agents, delayed systemic treatment was common. Fifty percent of patients reported experiencing at least 3 years of uncontrolled psoriasis before systemic therapy was initiated [25]. A similar trend for delayed therapy was observed in biologics. The disease duration of psoriasis ranges between 12 and 20 years for patients participating in biologic trials [26]. Nonetheless, the benefits of early aggressive strategy have been established in some inflammatory rheumatic diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis [27], Crohn’s disease [28], and ankylosing spondylosis [29]. A similar treatment algorithm of early aggressive intervention for psoriasis is still in its infancy, mainly because of the lack of apparent irreversible structural damage in psoriasis skin lesions [10]. The current treatment guidelines in psoriasis still recommend the use of biologics only in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, but do take into consideration the quality of life issue in addition to the skin severity, i.e., PASI, BSA, and PGA [7, 30]. In this study, unlike the definition of loss of PASI 50 proposed by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Advisory Board [31], relapse was defined as loss of PGA 0 or 1 or need of re-treatment with systemic therapy or phototherapy. Most of our patients initiated a systemic therapy before the loss of 50% of PASI improvement. A PGA ≥ 2 is more consistent with the decision to re-treat. PASI score is a non-linear scale that does not allow reliable measurement [28] of small affected or residual areas [32, 33], while PGA is more often used in long-term study in real-world practice [34, 35].

It appears that relapse occurs predominantly within the first 6 months regardless of different biologics. All patients in the efalizumab, alefacept, NAVIGATE study, and one JAK inhibitor study relapsed in the first 6 months. Higher 6 month relapse-free rates were observed in patients who used etanercept and those in the PEARL study, while they were lower for IL-17 and JAK inhibitor. Previous studies concluded that time to relapse was longest in responders who were withdrawn from alefacept, followed by ustekinumab, infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, and efalizumab despite different definitions of relapse, treatment durations, and numbers of subjects [36]. Specifically, median time to relapse for each biologic agent was 29.9 weeks (alefacept), 22 weeks (ustekinumab), 19.5 weeks (infliximab), 18 weeks (adalimumab), 12.1 weeks (etanercept), and 9.6 weeks (efalizumab), respectively, in this previous review [36]. Median time to relapse was between 24 and 28 weeks in different trials of secukinumab [37, 38]. The proportion of patients without relapse was 21% at 1 year and 10% at 2 years after discontinuation of 300 mg secukinumab [39]. As for tofacitinib, the median time to relapse was 16 weeks [24]. The median time to relapse (PASI ≤ 50) for ixekizumab was 20.4 weeks in Japanese patients who achieved PASI 75 after 1 year of treatment [40]. Another pooled analysis of ixekizumab revealed similar median relapse duration of approximately 20 weeks despite different relapse criteria set as static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPG) ≥ 3 [41]. At 6 and 12 months after ixekizumab discontinuation, 26% and 7% of patients retained their initial PASI 75 responses.

Factors such as treatment response, biologics naivety, family history of psoriasis, and use of immunosuppressant were reported to be significant predictors of relapse-free duration after withdrawal of ustekinumab [42]. In the current integrated analysis of data from various biologics, predictors of more effective disease control were identified as lower baseline PASI, PASI 90, biologics naivety, and early biologic use. Lower disease severity and significant improvement are related to longer remission. Findings in our study are consistent with previously reported results [42] and suggest an increasing role of biologics in the early stage of disease management. Hypotheses and ongoing studies are investigating the molecular and pathological modification caused by biological agents in psoriasis, especially when administered early and aggressively [9, 10]. In the survival analysis, better treatment response defined with PASI and biologics-naive treatment courses demonstrated lower relapse rates and longer drug-free periods. An early biologic intervention, i.e., within 2 years of diagnosis, is also associated with better treatment outcome in terms of relapse-free duration after cessation of systemic treatment. Although rapid response to ustekinumab was reported to be predictor of longer remission duration in a previous study [42], the difference between patients achieving PASI 75 within or later than 12 weeks was not significant (p = 0.250) when analyzed in our combined data set. Drug onset speed and duration of effect are dependent on mode of action [36, 43] and thus could account for this result.

In a prior study in Chinese psoriasis patients, six patterns of the natural course of psoriasis were described [44]. During the follow-up of three decades, 21.4% of patients suffered from only one episode of psoriasis, usually guttate type, which resolved within 1 year, and another 12.4% of patients experienced remission after 2 years of frequent attacks. Thus, it remains to be determined whether the longer remission observed in patients with shorter disease duration is due to disease modification from biologics or simply selecting out subjects who have a tendency for long-term remission by natural course irrespective of treatment. A controlled study has been initiated to answer this question by comparing remission duration between phototherapy and secukinumab treatment in new-onset psoriasis [10].

Biologics have demonstrated an overall favorable safety profile in psoriasis patients compared to conventional systemic therapy [45]. The rates of serious cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular accidents were 20, 7, and 3 events in a 4-year etanercept study of 506 patients, indicating an incidence rate of 1.5, 0.5, and 0.2 per 100 PY, respectively [46]. Our integrated data revealed a consistent safety profile. The cumulative rate of SAE was 1.5/100 PY. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death, happened in 12 participants in our study, giving an incidence rate of 0.8 per 100 PY, which is lower but not significant (p = 0.129) compared to the result from the 4-year etanercept experience [46]. Similar to our result, the event rate of MACE after secukinumab, despite dosage difference, was 0.7/100 PY. The incidence rate of cerebrovascular accidents in the pooled analysis of 11 studies was comparable at 0.5 events/100 PY (p = 0.426). Besides, the annual event rate per 100 patients for malignancies other than skin cancers was reported to be 0.61–0.63 in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who discontinued ustekinumab [47]. Five participants developed malignancy during our follow-up. The incidence rate was 0.3/100 PY but not significantly lower (p = 0.329). No SAE was monitored in one of the tofacitinib trials, IXORA-P, and NAVIGATE study, which is significantly lower (p = 0.046) when compared with other trials in our study.

Estimation of the prevalence rate of PsA in the general population is still in dispute, while in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis it is generally believed to be approximately 2–30% [48]. The incidence rate of PsA was 2.7 cases per 100 PY [48], and different epidemiologic surveys came to the same conclusion that the incidence rate has increased over the past decade [49, 50]. High prevalence of severe psoriasis was associated with patients with psoriatic arthritis [51], and paradoxical onset of arthritis was described after initiation of biologics such as etanercept and ustekinumab [52]. In our report, the incidence rate of PsA after withdrawal of biologics was 2.8/100 PY, which is compatible with the background 2.7/100 PY (p = 0.972). The incidence rate was not significantly different between each study when analyzed by Poison regression. Of note, the incidence rate reported here is in addition to the new onset or aggravation of existing arthritis occurring during clinical trials, which was efalizumab (28.6%) [13], alefacept (7%) [14], etanercept (5.84%) [16], ustekinumab (5%) [17], secukinumab (4.01%), [53]. secukinumab (10.75%), [19]. tofacitinib (7.58%) [20], ixekizumab (4.11%) [22], guselkumab (11.9%) [23].

Evident strengths of this 15-year experience are the real-world practice setting and the length of follow-up. Although the participants were trial subjects, the reinitiation of treatments was based on the need for systemic treatment, reflecting both the extent and stability of lesions as well as quality of life. This represented the actual clinical scenario in daily practice, and is consistent with the indication of current biologics i.e., moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy. This preliminary study has several potential limitations that should be considered. First, drugs with different modes of action and exposure duration were pooled together. It is theoretically not acceptable to combine the different biologic groups and analyze them even though it has been done and published by others. However, despite the different transcriptomic biomarker changes at early time points for drugs with different modes of action [54, 55], the residual disease genomic profile may be similar for successful treatment [56,57,58]. Individual drug or grouped drug action analysis would add to the article despite the small numbers. The second limitation is the retrospective study design. Nonetheless, most patients were followed by the same physician in the same clinic after the end of the studies as extensions of the prior controlled studies in a similar way until there is a need for systemic treatment. Third, there is a lack of control group and head-to-head study group to compare the adverse events as a result of a paucity of data. However, the pooled incidence risk seems comparable to the published data.

Conclusions

Despite the variety and efficacy of current biologics, systemic treatment was needed in 50–90.3% of patients within 12 months after treatment discontinuation, and biologics were reinitiated in 77.1% of patients after 3 years. However, early administration, namely within 2 years of diagnosis, of biological agents demonstrated a lower risk of relapse after discontinuation in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. The occurrence of SAE including PsA or MACE in the long-term follow-up was comparable to the published background incidence. However, it remains to be verified if early aggressive treatment actually alters the disease course of psoriasis, and whether medications with different modes of action share the same disease-modifying potentials.

References

Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):205–12.

Ko W-C, Tsai T-F, Tang C-H. Health state utility, willingness to pay, and quality of life among Taiwanese patients with psoriasis. Dermatol Sin. 2016;34(4):185–91.

Tsai T-F, Ho J-C, Chen Y-J, et al. Health-related quality of life among patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in Taiwan. Dermatol Sin. 2018;36(4):190–5.

Bechet PE. Psoriasis: a brief historical review. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1936;33(2):327–34.

Hawkes JE, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Psoriasis pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted immune therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):645–53.

Puig L. PASI90 response: the new standard in therapeutic efficacy for psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):645–8.

Tsai T-F, Lee C-H, Huang Y-H, et al. Taiwanese Dermatological Association consensus statement on management of psoriasis. Dermatol Sin. 2017;35(2):66–77.

Tsai TF, Wang TS, Hung ST, et al. Epidemiology and comorbidities of psoriasis patients in a national database in Taiwan. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63(1):40–6.

Gardinal I, Ammoury A, Paul C. Moderate to severe psoriasis: from topical to biological treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(11):1324–6.

Iversen L, Eidsmo L, Austad J, et al. Secukinumab treatment in new-onset psoriasis: aiming to understand the potential for disease modification—rationale and design of the randomized, multicenter STEPIn study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(11):1930–9.

Saraceno R, Griffiths CE. A European perspective on the challenges of managing psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(3 Suppl 2):S81–4.

Levin AA, Gottlieb AB, Au SC. A comparison of psoriasis drug failure rates and reasons for discontinuation in biologics vs conventional systemic therapies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(7):848–53.

Tsai TF, Liu MT, Liao YH, Licu D. Clinical effectiveness and safety experience with efalizumab in the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in Taiwan: results of an open-label, single-arm pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(3):345–52.

Huang PH, Liao YH, Wei CC, Tseng YH, Ho JC, Tsai TF. Clinical effectiveness and safety experience with alefacept in the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis in Taiwan: results of an open-label, single-arm, multicentre pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(8):923–30.

Sterry W, Ortonne JP, Kirkham B, et al. Comparison of two etanercept regimens for treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: PRESTA randomised double blind multicentre trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c147.

Strohal R, Puig L, Chouela E, et al. The efficacy and safety of etanercept when used with as-needed adjunctive topical therapy in a randomised, double-blind study in subjects with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (the PRISTINE trial). J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(3):169–78.

Tsai TF, Ho JC, Song M, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Taiwanese and Korean patients (PEARL). J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63(3):154–63.

Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326–38.

Thaci D, Blauvelt A, Reich K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: clear, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(3):400–9.

Papp KA, Menter MA, Abe M, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: results from two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(4):949–61.

Zhang J, Tsai TF, Lee MG, et al. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in Asian patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;88(1):36–45.

Langley RG, Papp K, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous every-2-week dosing of ixekizumab over 52 weeks in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in a randomized phase III trial (IXORA-P). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(6):1315–23.

Langley RG, Tsai TF, Flavin S, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):114–23.

Bissonnette R, Iversen L, Sofen H, et al. Tofacitinib withdrawal and retreatment in moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(5):1395–406.

Maza A, Richard MA, Aubin F, et al. Significant delay in the introduction of systemic treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: a prospective multicentre observational study in outpatients from hospital dermatology departments in France. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(3):643–8.

Tsai YC, Tsai TF. A review of clinical trials of biologic agents and small molecules for psoriasis in Asian subjects. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;151(4):412–31.

Sizova L. Approaches to the treatment of early rheumatoid arthritis with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(2):173–8.

Girolomoni G, Griffiths CE, Krueger J, et al. Early intervention in psoriasis and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a hypothesis paper. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(2):103–12.

Barkham N, Keen HI, Coates LC, et al. Clinical and imaging efficacy of infliximab in HLA-B27-positive patients with magnetic resonance imaging-determined early sacroiliitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(4):946–54.

Nast A, Spuls PI, van der Kraaij G, et al. European S3-Guideline on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris—update apremilast and secukinumab—EDF in cooperation with EADV and IPC. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(12):1951–63.

Gordon KB, Feldman SR, Koo JY, Menter A, Rolstad T, Krueger G. Definitions of measures of effect duration for psoriasis treatments. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(1):82–4.

Navarini AA, Poulin Y, Menter A, Gu Y, Teixeira HD. Analysis of body regions and components of PASI scores during adalimumab or methotrexate treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(5):554–62.

Otero ME, van Geel MJ, Hendriks JC, van de Kerkhof PC, Seyger MM, de Jong EM. A pilot study on the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) for small areas: presentation and implications of the low PASI score. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(4):314–7.

Menter A, Thaci D, Papp KA, et al. Five-year analysis from the ESPRIT 10-year postmarketing surveillance registry of adalimumab treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(3):410–9.

Moreno-Ramirez D, Ojeda-Vila T, Ferrandiz L. Disease control for patients with psoriasis receiving continuous versus interrupted therapy with adalimumab or etanercept: a clinical practice study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15(6):543–9.

Kamaria M, Liao W, Koo JY. How long does the benefit of biologics last? An update on time to relapse and potential for rebound of biologic agents for psoriasis. Psoriasis Forum. 2010;16(2):36–42.

Blauvelt A, Langley R, Szepietowski J, et al. Secukinumab withdrawal leads to loss of treatment responses in a majority of subjects with plaque psoriasis with retreatment resulting in rapid regain of responses: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 trials: 3719. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):AB273.

Mrowietz U, Leonardi CL, Girolomoni G, et al. Secukinumab retreatment-as-needed versus fixed-interval maintenance regimen for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial (SCULPTURE). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(1):27–36.

Martin G. Abstracts of poster presentations: mauiDerm 2017: March 20–24, 2017 Grand Wailea Maui, Hawaii. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(Suppl):S7–31.

Umezawa Y, Torisu-Itakura H, Morisaki Y, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety results from an open-label phase III study (UNCOVER-J) in Japanese plaque psoriasis patients: impact of treatment withdrawal and retreatment of ixekizumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(3):568–76.

Okubo Y, Mabuchi T, Iwatsuki K, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in Japanese patients with erythrodermic or generalized pustular psoriasis: subgroup analyses of an open-label, phase 3 study (UNCOVER-J). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(2):325–32.

Chiu H-Y, Hui RC, Tsai T-F, et al. Predictors of time to relapse following ustekinumab withdrawal in patients with psoriasis who had responded to therapy: an eight-year multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.035.

Papp KA, Lebwohl MG. Onset of action of biologics in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;17(3):247–50.

Koo K, Nakamura M, Lebwohl M. Article commentary: the natural course of psoriasis: data from a rare ‘experiment of nature’ in Maoist China. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2017;2(3):39–40.

Mansouri Y, Goldenberg G. Biologic safety in psoriasis: review of long-term safety data. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8(2):30–42.

Papp KA, Poulin Y, Bissonnette R, et al. Assessment of the long-term safety and effectiveness of etanercept for the treatment of psoriasis in an adult population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):e33–45.

Reich K, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. An update on the long-term safety experience of ustekinumab: results from the psoriasis clinical development program with up to four years of follow-up. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(3):300–12.

Eder L, Haddad A, Rosen CF, et al. The incidence and risk factors for psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(4):915–23.

Wang TS, Hsieh CF, Tsai TF. Epidemiology of psoriatic disease and current treatment patterns from 2003 to 2013: a nationwide, population-based observational study in Taiwan. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84(3):340–5.

Eder L, Widdifield J, Rosen CF, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in Ontario, Canada: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23743.

Busquets-Perez N, Rodriguez-Moreno J, Gomez-Vaquero C, Nolla-Sole JM. Relationship between psoriatic arthritis and moderate-severe psoriasis: analysis of a series of 166 psoriatic arthritis patients selected from a hospital population. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(1):139–43.

Napolitano M, Balato N, Caso F, et al. Paradoxical onset of psoriatic arthritis during treatment with biologic agents for plaque psoriasis: a combined dermatology and rheumatology clinical study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(1):137–40.

Wu NL, Hsu CJ, Sun FJ, Tsai TF. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in Taiwanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: subanalysis from ERASURE phase III study. J Dermatol. 2017;44(10):1129–37.

Visvanathan S, Baum P, Vinisko R, et al. Psoriatic skin molecular and histopathologic profiles after treatment with risankizumab versus ustekinumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;143:2158–69.

Brodmerkel C, Li K, Garcet S, et al. Modulation of inflammatory gene transcripts in psoriasis vulgaris: differences between ustekinumab and etanercept. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1965–9.

Tian S, Krueger JG, Li K, et al. Meta-analysis derived (MAD) transcriptome of psoriasis defines the “core” pathogenesis of disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44274.

Suarez-Farinas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Lowes MA, Krueger JG. Resolved psoriasis lesions retain expression of a subset of disease-related genes. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(2):391–400.

Zaba LC, Suarez-Farinas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with etanercept is linked to suppression of IL-17 signaling, not immediate response TNF genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(5):1021–395.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Tsen-Fang Tsai has conducted clinical trials or received honoraria for serving as a consultant for Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli-Lilly, Galderma, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Merck-Serono, Novartis International AG, and Pfizer Inc. Yi-Wei Huang has nothing to disclose. Tsen-Fang Tsai is a member of the journal’s Editorial Board.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

In accordance with the 1996 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, ethical approvals were obtained from National Taiwan University Research Ethics Committee for all trials. Informed consent corresponding to each study was explained. Sufficient time was allowed for questions and all subjects provided written informed consent forms prior to study participation. Mandatory Reporting of National Clinical Trial (NCT) Identifier of the trials were NCT00602823, NCT00422617, NCT00245960, NCT00663052, NCT01276639, NCT01815424, NCT02513550, NCT01365455, NCT01544595, NCT02074982, NCT00747344, NCT02203032.

Data Availability

The manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8307182.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, YW., Tsai, TF. Remission Duration and Long-Term Outcomes in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis Treated by Biologics or Tofacitinib in Controlled Clinical Trials: A 15-Year Single-Center Experience. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 9, 553–569 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-019-0310-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-019-0310-5