Abstract

Background

This prospective, open-label, non-comparative, multicentre, long-term phase IV study is examining the efficacy and safety of somatropin [recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH)] in short children born small for gestational age (SGA) and its impact on the incidence of diabetes. This report is the first interim analysis of patients who have completed 1 year of treatment.

Methods

A total of 278 pre-pubertal patients were enrolled. Key eligibility criteria included height standard deviation score (HSDS) <−2.5; parental adjusted SDS <−1; birth weight and/or length <−2 SD and failure to show catch-up growth by ≥4 years of age. Patients were treated with rhGH 0.035 mg/kg/day. The primary objective was to evaluate the long-term effect of rhGH on carbohydrate metabolism [including fasting glucose, stimulated glucose (2-h oral glucose tolerance test, OGTT) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c)]. Secondary objectives included evaluation of height parameters [body height, HSDS, height velocity (HV), HVSDS]; insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) serum levels during treatment; and incidence and severity of adverse events (AEs).

Results

None of the children developed diabetes mellitus within the first year of treatment. Mean levels of fasting glucose, HbA1c and 2-h OGTT values remained stable during the study period. Treatment with rhGH was effective, as documented by all height parameters. Mean HSDS improved from −3.39 at baseline to −2.57 at Year 1. Mean HV increased markedly from 4.25 cm/year at baseline to 8.99 cm/year during the first year. Similarly, mean peak-centred HVSDS increased from −2.13 at baseline to +4.16 at Year 1. Mean IGF-I SDS and IGFBP-3 SDS also increased within the first year (by +1.80 and +0.41, respectively). 13 patients (4.7%) did not respond adequately to treatment (HVSDS <1); they were withdrawn from the study. In total, 192 children (69.3%) experienced treatment-emergent AEs; most (98.7%) were mild-to-moderate, and the majority (96.5%) were unrelated to study treatment.

Conclusion

This interim analysis shows that short children born SGA can be effectively and safely treated with rhGH and that rhGH treatment has no major impact on carbohydrate metabolism after the first year of treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Infants with birth size small for gestational age (SGA) can represent up to 10% of all live births each year, depending on the definition used [1]. While the majority of children born SGA achieve appropriate catch-up growth by the age of 2–3 years, approximately one in ten does not, and these children are at increased risk of childhood and adult short stature [2, 3]. Therefore, current guidelines recommend early intervention [in the form of treatment with recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH), somatropin] for short children born SGA who still show severe growth retardation by 2–4 years of age [4]. In addition, epidemiological evidence suggests that children born SGA may also be at an increased risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in later life [5, 6] and there is also an association between low birth weight and later health problems, such as heart disease and stroke [4].

The efficacy and safety of GH therapy for children born SGA has been demonstrated in several studies [7–10]. However, given that GH therapy can induce transient insulin resistance in children [11], concerns exist over its diabetogenic potential in individuals inherently predisposed to metabolic abnormalities, such as children born SGA.

Currently, there is a paucity of long-term data on the use of rhGH therapy in short children born SGA, as well as its impact on diabetes. This ongoing, long-term, phase IV multicentre study with rhGH (Omnitrope®, Sandoz GmbH, Kundl, Austria) is the largest prospective clinical study of GH therapy in SGA patients conducted to date. The safety and efficacy of rhGH therapy will be thoroughly evaluated, especially in terms of its diabetogenic potential and its ability to stimulate growth. Here we report data from the first interim analysis of patients who have completed 1 year of treatment.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This is a prospective, open-label, non-comparative, multicentre, phase IV study in children born SGA.

Eligible patients are pre-pubertal (Tanner stage I) children born SGA with growth disturbances defined as current height standard deviation score (HSDS) <−2.5 (and parental adjusted SDS <−1) for chronological age and sex according to country-specific references. Additional inclusion criteria are birth weight and/or length <−2 SD for gestational age; failure of catch-up growth [height velocity (HV) SDS <0 during the last year] by 4 years of age or later; height records available between 18 months and 6 months before the start of GH treatment.

Key exclusion criteria include onset of puberty; closed epiphyses; diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2; fasting blood glucose >100 mg/dL or >5.6 mmol/L; abnormal 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT, >140 mg/dL or >7.8 mmol/L); acute critical illness; previous treatment with any GH preparation; treatment with antidiabetic medication (e.g. metformin, insulin); known insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I) level above +2 SD for gender and age; and drug, substance, or alcohol abuse. Patients were also excluded if they had any other disease, genetic disorder or treatment known to be associated with growth retardation, e.g. Turner or Noonan syndrome, Laron syndrome, Russell–Silver syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome, skeletal dysplasias, chronic renal failure, cystic fibrosis, heart and liver diseases, malabsorption (coeliac disease), malnutrition, or were receiving radiation therapy of the head or spinal cord.

The study protocol and all amendments were reviewed by the Independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board for each centre. All procedures followed were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008, and in compliance with Good Clinical Practice, with written informed consent obtained from the parent(s) or legal guardian(s) of all participants. Patients could voluntarily withdraw from the study at any time.

Study Treatment

Patients were treated with rhGH 0.035 mg/kg/day by subcutaneous injection in the evening. The investigator trained the patients (or their legal guardians) to administer the study drug as prescribed. Doses had to be adjusted at each study visit within defined limits. Concomitant medications could be given at the investigator’s discretion.

Study Objectives

The primary objective is to evaluate the long-term effect of rhGH treatment on the development of diabetes mellitus in short children born SGA. In this paper we present data after 1-year of follow-up.

Secondary objectives include an evaluation of efficacy through changes in height parameters; measurement of rhGH-induced serum markers IGF-I and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3); incidence and severity of adverse events (AEs) and detection of anti-rhGH antibodies during treatment.

Timing of Assessments

Height was measured in cm and HV calculated. HSDS and HVSDS (based on country-specific reference tables) were assessed at baseline and at 3-month intervals throughout the first year. To determine bone age, X-rays of the left hand and wrist were obtained at baseline and once-yearly thereafter.

IGF-I and IGFBP-3 were measured by a central laboratory at screening and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months thereafter. IGF-I and IGFBP-3 serum levels were categorised as low (<−2 SD), normal, or high (>+2 SD), compared with the normal ranges, and serum level changes from baseline to Year 1 were analysed.

Fasting plasma glucose, 2-h OGTT, HbA1c and insulin levels were measured at baseline, 6 months, 12 months and annually thereafter. Homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) score (marker of insulin resistance) and the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) were calculated as previously described [12–14].

All AEs were recorded at each visit and their incidence is reported using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) preferred terms, version 14.0 or higher [15].

Treatment Failure

Treatment was discontinued after 1 year if HVSDS <1 (i.e. the patient is classed as a non-responder). All responders will continue treatment until final height is reached [HV <2 cm/year and/or confirmed bone age of >14 years (girls) or >16 years (boys)]. In cases where the investigator does not agree with the outcome of the central assessment of treatment failure (based on height measurement), the treatment response is reassessed by an independent bone-age reader.

Like all patients that are treated within this study, patients classed as “non-responders” are also offered the option to participate in a 10-year follow-up safety study (EP00-402; NCT01491854). During this 10-year follow-up, all patients included will be analysed for safety, with particular emphasis on the development of diabetes after the end of rhGH therapy.

Additional Safety Assessments

Physical examinations and vital signs were performed at each scheduled visit. Haematology, blood chemistry, thyroid function tests [free thyroxine (FT4) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels], lipids and urinalysis were assessed at baseline, 6 months and Year 1. Patients with hypothyroidism, who were untreated, inadequately treated or had been treated for less than 3 months, were excluded from the study.

Anti-GH antibodies were measured centrally using a previously validated radio-binding assay for non-neutralizing anti-GH antibodies, using radiolabelled (125I) rhGH as a ligand. The results are reported in index units calculated from a normal pool. The cut-off value (high reference range) for determining whether patients had developed anti-GH antibodies was 1.76.

Statistical Analyses and Patient Populations

The current analysis includes data from baseline up to the 1-year visit. Further analyses are planned for 2013 (2 year-visit) and 2021 (end of treatment).

All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1.3 or later (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). The probability for developing diabetes mellitus was calculated using the Poisson distribution. HOMA, QUICKI, IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and standard deviation scores (SDS) for IGF-I and IGFBP-3 were evaluated using descriptive statistics. Bone age (BA) and height age (HA) were derived during the analysis. Mean values and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were also calculated for males and females. Paired t tests were used to calculate p values, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05. The intent-to-treat (ITT) population comprised all subjects enrolled in the study who received at least one dose of study medication. The safety population consisted of all patients who received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one post-baseline safety assessment.

Results

Patients

A total of 32 centres have recruited and treated patients: 14 centres in Poland, 6 in Romania, 5 in Hungary, 3 in Czech Republic, 2 in Germany, 1 in Belgium and 1 in Georgia.

The study commenced in February 2008. At the time of database lock for this first interim analysis (19 October 2011) 333 patients had been screened, and 278 were enrolled into the study and received study medication. Of these, 277 had at least one post-baseline visit and 269 had completed their first year of treatment. The majority of patients were compliant with treatment (99.3% at the 12-month visit). Patient disposition is shown in Fig. 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Slightly more patients were males (53.2%) than females, mean age on admission to the study was 7.4 years (range 4–14 years) and almost all patients (98.9%) were of Caucasian ethnicity. Birth history was similar for boys and girls.

Impact of rhGH on Diabetes (Primary Endpoint)

The development of diabetes was evaluated by the fasting plasma glucose and 2-h OGTT. According to these assays, none of the children developed diabetes mellitus within the first year of treatment, since no fasting glucose or 2-h OGTT value exceeded the pre-defined upper limits (>126 or >200 mg/dL, respectively). Similarly, mean levels of HbA1c did not increase during the first year of treatment (5.3 at baseline and 5.4 at Year 1) (Table 2). Transient increases in fasting glucose occurred in 23 patients (8.3%), while 15 patients (5.1%) experienced transient impaired glucose tolerance.

Mean (±SD) HOMA score increased slightly from baseline (1.01 ± 1.03) to Year 1 (1.57 ± 1.11), while the QUICKI score decreased slightly from baseline (0.42 ± 0.10) to Year 1 (0.38 ± 0.05). These changes were considered by the investigators as not clinically significant. Shift table analyses of glucose parameters indicated that the majority of patients had normal values at baseline, which remained within this range at Year 1 (data not shown). Overall, there were no significant abnormalities in glucose parameters during the first year of treatment.

Impact of rhGH Treatment on BMI

Mean (SD) BMI SDS at baseline was −1.54 (1.36). This changed on slightly, to −1.64 (1.25), at Year 1.

Pubertal Status

Only pre-pubertal children were enrolled in the study (Table 1) and their pubertal status was monitored throughout. The vast majority of children remained pre-pubertal (Tanner stage I) from baseline to Year 1 [n = 216 (80.3%)]. No children reached Tanner stage V, but there were a few that reached Tanner stage II [n = 41 (15.2%)], III [n = 10 (3.7%)], or IV [n = 2 (0.7%)].

Additional Safety Assessments

A total of 649 treatment-emergent AEs were reported in 192 children (69.3%); most (98.7%) were mild-to-moderate in intensity and the majority (96.5%) were judged to be unrelated to study treatment.

The most frequently occurring AEs (by MedDRA preferred term) were nasopharyngitis (n = 53, 19.1%), pharyngitis (n = 51, 18.4%), upper respiratory tract infections (n = 25, 9%) and bronchitis (n = 23, 8.3%) (Table 3). AEs with a suspected relationship to study drug were rare; the most frequently reported were hypothyroidism (7 patients, 2.5%) and headache (3 patients, 1.1%).

Serious AEs were reported in 19 patients (6.9%), with only one suspected to be treatment-related (severe headache). No malignancies have been observed in the study to date, no patients have died during the first year of treatment and only one patient discontinued from the study due to a non-serious AE (crying, aggressiveness and refusing to take injections), which was considered unrelated to the study drug.

In total, 17 children had a positive anti-hGH antibody titre at one time point during the study. The number of patients with anti-hGH antibodies appeared to increase slightly over time but remained at a low level, with only seven patients (2.9%) testing positive at the 1-year visit.

Mean (SD) FT4 levels changed significantly (p < 0.0001) from baseline [16.42 (3.02) pmol/L, n = 268] to Year 1 [15.27 (2.78) pmol/L, n = 263]. TSH levels remained constant throughout the first year of treatment [baseline 2.84 (1.32) mU/L, n = 271; Year 1: 2.86 (1.42) mU/L, n = 265].

There were no clinically significant findings in haematological parameters, blood chemistry, urinalysis, or vital signs.

Efficacy Assessments (Secondary Endpoints)

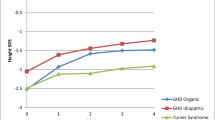

Body height increased steadily throughout the treatment period; mean changes from baseline were slightly greater in girls (9.29 cm) than in boys (8.90 cm). Likewise, mean HSDS showed a continuous increase and improved by 0.81 overall (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). While this reflects a net improvement of height, the values achieved indicate that the mean height of the study population was still shorter than average after 1 year of treatment.

Mean HV increased markedly during the first 3 months of treatment (10.72 cm/year compared with 4.25 cm/year at baseline; p < 0.0001) and then decreased slightly but remained higher than at baseline (8.99 cm/year after 1 year; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3a). There was no apparent difference between boys and girls in terms of mean change in HV (4.69 versus 4.79, respectively). Similarly, mean peak-centred HVSDS initially increased markedly from a negative value at baseline (−2.13), reaching 6.31 after 3 months (p < 0.0001) and remaining high (4.16) by Year 1 (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3b).

A small number of children (13/278, 4.7%) did not respond adequately to treatment after the first year (HVSDS <1) and were withdrawn from treatment.

IGF-I and IGFBP-3

IGF-I and IGFBP-3 were measured as surrogate indicators of treatment efficacy. Mean IGF-I SDS showed a steady increase from baseline (−1.08) to Year 1 (+0.72) (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4a). Shifts in IGF-I serum level categories indicated that at baseline most patients had normal (n = 208; 77.3%) or low (<−2 SD) IGF-I levels (n = 44; 16.4%). At 1 year, this distribution shifted, so that only two patients had low levels and the majority had normal (n = 202; 75.1%) or high (n = 40; 14.9%) IGF-I levels.

Mean IGFBP-3 SDS was +0.11 at baseline, increasing to +0.52 at Year 1 (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4b). Shifts in IGFBP-3 serum level categories showed that the majority of patients (n = 247; 91.8%) had normal IGFBP-3 levels at baseline. At Year 1, this distribution was essentially unchanged, with 232 patients (86.2%) having normal levels of IGFBP-3.

Molar IGF-I/IGFBP-3 ratios increased throughout the first year, and had almost doubled by Year 1, compared with baseline [0.23 versus 0.12, respectively; mean difference 0.11 (p < 0.0001)].

Discussion

Short children born SGA are predisposed to metabolic abnormalities, with the pattern of carbohydrate metabolism typically one of compensated insulin resistance without obvious abnormality of fasting or post-prandial glucose [16]. GH treatment, with its insulin antagonistic action, could potentially increase the risk of type 2 diabetes in this patient group [11].

The main objective of the present study is to evaluate the effect of rhGH treatment on the development of diabetes in short children born SGA. In this first interim analysis, no patients developed diabetes during the first year of treatment. Glucose levels (fasting plasma glucose), glucose tolerance (OGTT) and HbA1c remained stable over the first year of treatment, while fasting insulin increased slightly. These findings are consistent with the concept that, while GH treatment may increase insulin resistance in children born SGA, there is a compensatory hyperinsulinaemia that maintains normal glucose regulation during treatment [17].

These 1-year interim data are also consistent with data from a study of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity during GH treatment of 84 children born SGA, which reported that while a reduction in insulin sensitivity was observed, glucose tolerance remained normal [10]. In addition, other recent studies in children born SGA reported that any rhGH-induced changes in insulin levels reverted to normal upon treatment discontinuation, while fasting blood glucose remained within normal limits during a 2-year treatment period [18].

The incidence of anti-rhGH antibodies during the first year of treatment was low. This is consistent with findings from other longer-term studies examining the efficacy and safety of rhGH in children with GH deficiency, which have also reported low levels of anti-rhGH antibodies after 4–7 years of treatment [19, 20].

The incidence of treatment-related hypothyroidism (2.5%) and headache (1.1%) reported in this study was comparable to other clinical trials. Moreover, it is generally recognised that rhGH therapy has a good safety profile in children born SGA [1].

The increase in growth velocity and height gain during the first year of GH treatment in the present study was excellent and compares favourably with data reported in several other studies of SGA children treated with various rhGH products [7–10, 16].

When treating children born SGA, it is important to define an acceptable level of response to GH therapy so that decisions can be made promptly to discontinue treatment in the event of treatment failure. A change in HSDS <0.2 in a child aged 5 years has been proposed as a clinically insignificant response [21]. However, consensus guidelines consider a positive growth response within the first year of GH treatment as a change in HVSDS of more than +0.5 [4]. In the present study, this was achieved in all patients classified as responders, since the study protocol applied a stricter definition, i.e. HVSDS had to be at least +1 after the first year of treatment for patients to be eligible to continue with therapy.

An obvious limitation of the study is the lack of an (untreated) control group. Another potential limitation is that most patients were older than 4 years at initiation of rhGH therapy. However, the statistically significant treatment benefits that were observed in the majority of patients across all height parameters indicate that this is a GH-responsive population. The few non-responsive patients were withdrawn from the study at the 1-year visit, as stipulated by the approved study protocol.

Conclusions

The results of this first interim analysis show that short children born SGA can be effectively and safely treated with rhGH (Omnitrope®). Further scheduled interim analyses and the final analysis of this study, which is the largest prospective clinical study of rhGH treatment in SGA patients conducted to date, will enable a more comprehensive and conclusive assessment of long-term safety and efficacy in this patient population.

References

Saenger P, Czernichow P, Hughes I, Reiter EO. Small for gestational age: short stature and beyond. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:219–51.

Lee PA, Chernausek SD, Hokken-Koelega AC, et al. International Small for Gestational Age Advisory Board consensus development conference statement: management of short children born small for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1253–61.

Albertsson-Wikland K, Karlberg J. Postnatal growth of children born small for gestational age. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1997;423:193–5.

Clayton PE, Cianfarani S, Czernichow P, Johannsson G, Rapaport R, Rogol A. Management of the child born small for gestational age through to adulthood: a consensus statement of the International Societies of Pediatric Endocrinology and the Growth Hormone Research Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:804–10.

Bhargava SK, Sachdev HS, Fall CH, et al. Relation of serial changes in childhood body-mass index to impaired glucose tolerance in young adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:865–75.

Eriksson JG, Osmond C, Kajantie E, Forsén TJ, Barker DJ. Patterns of growth among children who later develop type 2 diabetes or its risk factors. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2853–8.

Sas T, De Waal W, Muler P, et al. Growth hormone treatment in children with short stature born small for gestational age: 5-year results of a randomized, double-blind, dose-response trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3064–70.

Sas TC, Gerver WJ, De Bruin R, et al. Body proportion during 6 years of GH treatment in children with short stature born small for gestational age participating in a randomised, double-blind, dose-response trial. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000;53:675–81.

Czernichow P. Growth hormone treatment strategy for short children born small for gestational age. Horm Res. 2004;62:137–40.

Cutfield WS, Lindberg A, Rapaport R, Wajnrajch MP, Saenger P. Safety of growth hormone treatment in children born small for gestational age: the US trial and KIGS analysis. Horm Res. 2006;65(Suppl 3):153–9.

Delemarre EM, Rotteveel J, Delemarre-van der Waal HA. Metabolic implications of GH treatment in small for gestational age. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157:S47–50.

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–9.

Katz A, Nambi SS, Malther K, et al. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2000;85:2402–10.

World Health Organisation (WHO). Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia. Report of a WHO/IDF consultation; 2006. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241594934_eng.pdf (Accessed January 13, 2014).

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) preferred terms, version 14.0 or higher. http://www.meddra.org/how-to-use/support-documentation (Accessed January 13, 2014).

Jung H, Rosilio M, Blum WF, Drop SL. Growth hormone treatment for short stature in children born small for gestational age. Adv Ther. 2008;25:951–78.

Cutfield WS, Jackson WE, Jefferies C, et al. Reduced insulin sensitivity during growth hormone therapy for short children born small for gestational age. J Pediatr. 2003;142:113–6.

Lebl J, Lebenthal Y, Kolouskova S, et al. Metabolic impact of growth hormone treatment in short children born small for gestational age. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76:254–61.

Romer T, Saenger P, Peter F, et al. Seven years of safety and efficacy of the recombinant human growth hormone Omnitrope® in the treatment of growth hormone deficient children: results of a phase III study. Horm Res. 2009;72:359–69.

López-Siguero J, Borrás Pérez MV, Balser S, Khan-Boluki J. Long-term safety and efficacy of the recombinant human growth hormone Omnitrope® in the treatment of Spanish growth hormone deficient children: results of a phase III study. Adv Ther. 2011;28:879–93.

Omokanye A, Onyekpe I, Patel L, et al. Defining criteria for poor responders to growth hormone (GH) in short children born small for gestational age (SGA). 37th meeting of the British Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, Reading; 2009 (Endocrine Abstracts 23 P10).

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals.

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were funded by Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals. Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this paper was provided by Tony Reardon of Spirit Medical Communications Ltd and funded by Sandoz International GmbH.

All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

H.P. Schwarz has received fees from Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals/Hexal AG as International Co-ordinating Investigator for the EP00-401 and EP00-402 studies.

J. Khan-Boluki is an employee of Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals.

E. Schuck is an employee of Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals.

D. Birkholz-Walerzak, M. Szalecki, M. Walczak, C. Galesanu and D.Metreveli declare no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The study protocol and all amendments were reviewed by the Independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board for each centre. All procedures followed were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008 and in compliance with Good Clinical Practice, with written informed consent obtained from the parent(s) or legal guardian(s) of all participants. Patients could voluntarily withdraw from the study at any time.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

ClinicalTrial.gov # NCT00537914; EudraCT number: 2006-002506-58.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwarz, HP., Birkholz-Walerzak, D., Szalecki, M. et al. One-Year Data from a Long-Term Phase IV Study of Recombinant Human Growth Hormone in Short Children Born Small for Gestational Age. Biol Ther 4, 1–13 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13554-014-0014-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13554-014-0014-4