Abstract

Changes in fertility patterns are hypothesized to be among the many second-order consequences of armed conflict, but expectations about the direction of such effects are theoretically ambiguous. Prior research, from a range of contexts, has also yielded inconsistent results. We contribute to this debate by using harmonized data and methods to examine the effects of exposure to conflict on preferred and observed fertility outcomes across a spatially and temporally extensive population. We use high-resolution georeferenced data from 25 sub-Saharan African countries, combining records of violent events from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) with data on fertility goals and outcomes from the Demographic and Health Surveys (n = 368,765 women aged 15–49 years). We estimate a series of linear and logistic regression models to assess the effects of exposure to conflict events on ideal family size and the probability of childbearing within the 12 months prior to the interview. We find that, on average, exposure to armed conflict leads to modest reductions in both respondents’ preferred family size and their probability of recent childbearing. Many of these effects are heterogeneous between demographic groups and across contexts, which suggests systematic differences in women’s vulnerability or preferred responses to armed conflict. Additional analyses suggest that conflict-related fertility declines may be driven by delays or reductions in marriage. These results contribute new evidence about the demographic effects of conflict and their underlying mechanisms, and broadly underline the importance of studying the second-order effects of organized violence on vulnerable populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

All data sets used are publicly available from the DHS, ACLED, and UCDP. Programming code is available upon request from Brian Thiede.

Notes

The casualty figure is for all African countries from the period January 1, 2000–January 1, 2018. It includes deaths from intrastate and interstate conflicts, violent protests, terrorism, and government violence against civilians.

Evidence of such weak institutions and political instability comes from the World Bank’s Governance Effectiveness and Political Stability and Absence of Violence indicators. Both indicators range between –2.50 and 2.50. For 1996–2018, our sample’s mean score is –0.75 for Governance Effectiveness and –0.65 for Political Stability and Absence of Violence.

Fertility may also increase in response to perceived child mortality risk due to conflict (i.e., “insurance effects”). However, such processes would require women to perceive that conflict will increase mortality risk over sustained periods, which has not been demonstrated empirically.

One study that has used high-resolution conflict and demographic data across a large multinational population focused on maternal and child health rather than fertility (Østby et al. 2018).

DHS estimates are nationally representative when survey weights are applied.

The DHS has implemented multiple phases of the survey, and in some cases, response options are tailored to the local context. However, the data sets and variables included in our analytic sample were sufficiently alike to permit harmonization. The use of IPUMS-DHS data also facilitated harmonization for many countries in the sample (Boyle et al. 2018).

The countries (samples) in our data are Angola (2015), Benin (2001), Burkina Faso (2003), Burundi (2016–2017), Cameroon (2004), Democratic Republic of the Congo (2007), Eswatini (2006), Ethiopia (2000, 2005, 2016), Ghana (2003, 2006), Guinea (2005), Kenya (2003, 2008–2009), Lesotho (2004, 2009), Liberia (2007), Madagascar (2008), Malawi (2000, 2004, 2010, 2016), Mali (2001, 2006), Namibia (2000, 2006), Nigeria (2003, 2008), Rwanda (2005), Senegal (2005), Sierra Leone (2008), Tanzania (2004, 2015), Uganda (2001, 2006, 2016), Zambia (2007, 2013), and Zimbabwe (2005–2006, 2015).

See Table A1 (online appendix) for the distribution of observations by country and the proportion of each sample exposed to conflict, as defined in the main specification.

We exclude nonnumeric responses (e.g., “up to God”) from the analysis. The prevalence of such responses is typically less than 10% and has declined over time in sub-Saharan Africa (Frye and Bachan 2017).

ACLED includes other categories of violent events, such as violence against civilians and violent protests or riots. We exclude such events for two reasons. First, we are interested in the effects of armed conflict specifically rather than unrest and instability in general. Second, comparable measures for these types of violence are not available in the UCDP database, which we use to test the robustness of our findings with ACLED.

We account for the error around GPS coordinates in the public-use DHS data by defining a 10-km radius as the minimum buffer in our analysis. The DHS program randomly displaces the GPS coordinates for all clusters to maintain confidentiality. The coordinates are displaced by 0–2 km for urban clusters and by 0–5 km for rural clusters, with 1% of rural clusters displaced by 0–10 km (Burgert et al. 2013). Our approach is consistent with that of other high-quality sources, including the DHS program’s own geospatial data set and IPUMS-DHS.

Some countries and regions in the sample did not experience conflict events during the study period. We check the robustness of our results to excluding these places from the analytic sample in Models A1–A4 of the online appendix.

We assume a nine-month gestational period and that the average birth during the prior 12 months occurred at the midpoint of the interval.

Models of any contraceptive use (current or previous) yield similar results.

The number of children ever born is excluded as a control in the model of women’s marital status. Although premarital childbearing is common and/or increasing in some parts of the region, a substantial majority of women still do not have a child before marriage (Clark et al. 2017), raising concerns about endogeneity.

Women who recently had children are less likely to be using contraception because of ongoing breastfeeding. We therefore estimate an identical model of current contraceptive use limited to the sample of women who did not have a child within the past 12 months (Model A5, Table A6; online appendix). We also estimate a comparable model that predicts unmet need for family planning (Model A6, Table A7). We find no statistically significant conflict effects in either model.

Some analyses of fertility ideals have focused on this subpopulation under the assumption that such women’s ideal family size is more dynamic and less prone to ex post rationalization (Bongaarts and Casterline 2013).

References

Adhikari, P. (2012). Conflict-induced displacement, understanding the causes of flight. American Journal of Political Science, 57, 82–89.

Agadjanian, V., & Prata, N. (2002). War, peace, and fertility in Angola. Demography, 39, 215–231.

Agadjanian, V., Yabiku, T., & Boaventura, C. (2011). Men’s migration and women’s fertility in rural Mozambique. Demography, 48, 1029–1048.

Akresh, R., Lucchetti, L., & Thirumurthy, H. (2012). Wars and child health: Evidence from the Eritrean–Ethiopian conflict. Journal of Development Economics, 99, 330–340.

Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). (2019). Available online at https://www.acleddata.com/data/

Behrman, J. A. (2015). Does schooling affect women’s desired fertility? Evidence from Malawi, Uganda, and Ethiopia. Demography, 52, 787–809.

Berrebi, C., & Ostwald, J. (2015). Terrorism and fertility: Evidence for a causal influence of terrorism on fertility. Oxford Economic Papers, 67, 63–82.

Blake, J. (1981). Family size and the quality of children. Demography, 18, 421–442.

Blanc, A. (2004). The role of conflict in the rapid fertility decline in Eritrea and prospects for the future. Studies in Family Planning, 35, 236–245.

Bohra-Mishra, P., & Massey, D. S. (2011). Individual decisions to migrate during civil conflict. Demography, 48, 401–424.

Bongaarts, J. (1990). The measurement of unwanted fertility. Population and Development Review, 16, 487–506.

Bongaarts, J. (2001). Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. Population and Development Review, 27, 260–281.

Bongaarts, J., & Casterline, J. (2013). Fertility transition: Is sub-Saharan Africa different? Population and Development Review, 38, 153–168.

Boyle, E. H., King, M., & Sobek, M. (2018). IPUMS-Demographic and Health Surveys: Version 5 [Data set]. Minneapolis: Minnesota Population Center and ICF international. https://doi.org/10.18128/D080.V5

Brunborg, H., & Urdal, H. (2005). The demography of conflict and violence: An introduction. Journal of Peace Research, 42, 371–374.

Buhaug, H., & Rød, J. K. (2006). Local determinants of African civil wars, 1970–2001. Political Geography, 25, 315–335.

Burgert, C. R., Colston, J., Roy, T., & Zachary, B. (2013). Geographic displacement procedure and georeferenced data release policy for the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS Spatial Analysis Reports No. 7). Calverton, MD: ICF International.

Caldwell, J. C. (1976). Toward a restatement of demographic transition theory. Population and Development Review, 2, 321–366.

Caldwell, J. C. (2004). Social upheaval and fertility decline. Journal of Family History, 29, 384–406.

Casterline, J. B., & El-Zeini, L. O. (2007). The estimation of unwanted fertility. Demography, 44, 729–745.

Cetorelli, V. (2014). The effect on fertility of the 2003–2011 war in Iraq. Population and Development Review, 40, 581–604.

Chi, P. C., Bulage, P., Urdal, H., & Sundby, J. (2015). Perceptions of the effects of armed conflict on maternal and reproductive health services and outcomes in Burundi and northern Uganda: A qualitative study. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0045-z

Clark, S., Koski, A., & Smith-Greenaway, E. (2017). Recent trends in premarital fertility across sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 48, 3–22.

Coale, A. (1973). The demographic transition reconsidered. In International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Population Conference (Vol. 1, pp. 53–72). Liege, Belgium: Editions Ordina.

Cohen, D. K., & Nordås, R. (2014). Sexual violence in armed conflict: Introducing the SVAC dataset, 1989–2009. Journal of Peace Research, 51, 418–428.

Collier, P., Elliot, V. L., Hegre, H., Hoeffler, A., Reynal-Querol, M., & Sambanis, N. (2003). Breaking the conflict trap: Civil war and development policy (World Bank Policy Research Report No. 26121). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Corno, L., Hildebrandt, N., & Voena, A. (2017). Age of marriage, weather shocks, and the direction of marriage payments (NBER Working Paper No. 23604). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Czaika, M., & Kis-Katos, K. (2009). Civil conflict and displacement: Village-level determinants of forced migration in Aceh. Journal of Peace Research, 46, 399–418.

Dabalen, A., & Paul, S. (2014). Estimating the effects of conflict on education in Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Development Studies, 50, 1631–1646.

Dossa, N. I., Zunzunegui, M. V., Hatem, M., & Fraser, W. (2014). Fistula and other adverse reproductive health outcomes among women victims of conflict-related sexual violence: A population-based cross-sectional study. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 41, 5–13.

Eloundou-Enyegue, P. M., & Giroux, S. C. (2012). Demographic change and rural-urban inequality in sub-Saharan Africa: Theory and trends. In L. J. Kulcsár & K. J. Curtis (Eds.), International handbook of rural demography (pp. 125–135). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Frye, M., & Bachan, L. (2017). The demography of words: The global decline in non-numeric fertility preferences, 1993–2011. Population Studies, 71, 187–209.

Gerland, P., Raftery, A., Ševčíková, H., Danan Gu, H., Spoorenberg, T., & Alkema, L. (2014). World population stabilization: Unlikely this century. Science, 346, 234–237.

Ghobarah, H., Huth, P., & Russett, B. (2003). Civil wars kill and maim people—Long after the shooting stops. American Political Science Review, 97, 189–202.

Hagan, J., Rymond-Richmond, W., & Palloni, A. (2009). Racial targeting of sexual violence in Darfur. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 1386–1392.

Hayford, S. R., & Agadjanian, V. (2011). Uncertain future, non-numeric preferences, and the fertility transition: A case study of rural Mozambique. African Population Studies, 25, 419–439. https://doi.org/10.11564/25-2-239

Hossain, M., Phillips, J. F., & Legrand, T. K. (2007). The impact of childhood mortality on fertility in six rural thanas of Bangladesh. Demography, 44, 771–784.

Human Rights Watch. (2008). Collective punishment: War crimes and crimes against humanity in the Ogaden area of Ethiopia’s Somali regional state. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch.

Islam, A., Ouch, C., Smyth, R., & Choon Wang, L. (2016). The long-term effects of civil conflicts on education, earnings, and fertility: Evidence from Cambodia. Journal of Comparative Economics, 44, 800–820.

Korf, B. (2004). War, livelihoods and vulnerability in Sri Lanka. Development and Change, 35, 275–295.

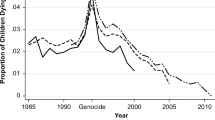

Kraehnert, K., Brück, T., Di Maio, M., & Nisticò, R. (2019). The effects of conflict on fertility: Evidence from the genocide in Rwanda. Demography, 56, 935–968.

Lindskog, E. (2016). Effects of violent conflict on women and children: Sexual behavior, fertility, and infant mortality in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Doctoral dissertation). Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University, Department of Sociology.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Berhanu, B. (1999). The impact of war, famine, and economic decline on marital fertility in Ethiopia. Demography, 36, 247–261.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Kiros, G.-E. (2007). The impact of infant and child death on subsequent fertility in Ethiopia. Population Research and Policy Review, 26, 31–49.

McGinn, T. (2000). Reproductive health of war-affected populations: What do we know? International Family Planning Perspectives, 26, 174–180.

McGinn, T., Austin, J., Anfinson, K., Amsalu, R., Casey, S. E., Fadulalmula, S. I., . . . Yetter, M. (2011). Family planning in conflict: Results of cross-sectional baseline surveys in three African countries. Conflict and Health, 5, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-5-11

Minoiu, C., & Shemyakina, O. (2012). Child health and conflict in Côte d’Ivoire. American Economic Review, 102, 294–299.

Nobles, J., Frankenberg, E., & Thomas, D. (2015). The effects of mortality on fertility: Population dynamics after a natural disaster. Demography, 52, 15–38.

Olsen, R. (1980). Estimating the effect of child mortality on the number of births. Demography, 17, 429–443.

Østby, G. (2016, September). Violence begets violence: Armed conflict and domestic sexual violence in sub-Saharan Africa. Paper presented at the Workshop on Sexual Violence and Armed Conflict, New Research Frontiers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Østby, G., Urdal, H., Tollefsen, A. F., Kotsadam, A., Belbo, R., & Ormhaug, C. (2018). Organized violence and institutional child delivery: Micro-level evidence from sub-Saharan Africa, 1989–2014. Demography, 55, 1295–1316.

Pallitto, C. C., & O’Campo, P. (2004). The relationship between intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy: Analysis of a national sample from Colombia. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30, 165–173.

Palmer, J. J., & Storeng, K. T. (2016). Building the nation’s body: The contested role of abortion and family planning in post-war South Sudan. Social Science & Medicine, 168, 84–92.

Peterman, A., Palermo, T., & Bredenkamp, C. (2011). Estimates and determinants of sexual violence against women in the Democratic Republic of Congo. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 1060–1067.

Raleigh, C., Linke, A., Hegre, H., & Karlsen, J. (2010). Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset: Special data feature. Journal of Peace Research, 47, 651–660.

Sahn, D. E., & Stifel, D. C. (2003). Urban-rural inequality in living standards in Africa. Journal of African Economies, 12, 564–597.

Schindler, K., & Brück, T. (2011). The effects of conflict on fertility in Rwanda (Policy Research Working Paper No. WPS 5715). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Smith-Greenaway, E., & Clark, S. (2018). Women’s marriage behavior following a premarital birth in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80, 256–270.

Smith-Greenaway, E., & Trinitapoli, J. (2014). Polygynous contexts, family structure, and infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Demography, 51, 341–366.

Sundberg, R., & Melander, E. (2013). Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset. Journal of Peace Research, 50, 523–532.

Torche, F., & Shwed, U. (2015). The hidden costs of war: Exposure to armed conflict and birth outcomes. Sociological Science, 2, 558–581. https://doi.org/10.15195/v2.a27

Torres, A. F. C., & Urdinola, B. P. (2019). Armed conflict and fertility in Colombia, 2000–2010. Population Research and Policy Review, 38, 173–213.

Tsui, A. O., Brown, W., & Li, Q. (2017). Contraceptive practice in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review, 43(S1), 166–191.

United Nations Statistics Division. (1999). Standard country or area codes for statistical use, 1999 (Rev. 4). New York, NY: United Nations.

Urdal, H. (2006). A clash of generations? Youth bulges and political violence. International Studies Quarterly, 50, 607–629.

Urdal, H., & Che, C. P. (2013). War and gender inequalities in health: The impact of armed conflict on fertility and maternal mortality. International Interactions, 39, 489–510.

Verwimp, P., & van Bavel, P. (2005). Child survival and fertility of refugees in Rwanda. European Journal of Population, 21, 271–290.

Williams, N. E. (2013). How community organizations moderate the effect of armed conflict on migration in Nepal. Population Studies, 67, 353–369.

Williams, N. E., Ghimire, D. J., Axinn, W. G., Jennings, E. A., & Pradhan, M. S. (2012). A micro-level event-centered approach to investigating armed conflict and population responses. Demography, 49, 1521–1546.

Williams, P. D. (2017). Continuity and change in war and conflict in Africa. Prism, 6(4), 32–45.

Woldemicael, G. (2008). Recent fertility decline in Eritrea: Is it a conflict-led transition? Demographic Research, 18, 27–58. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.18.2

Woldemicael, G. (2010). Declining fertility in Eritrea since the mid-1990s: A demographic response to military conflict. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 4, 150–168. https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-2821

Wood, E. J. (2014). Conflict-related sexual violence and the policy implications of recent research. International Review of the Red Cross, 96, 457–478. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383115000077

World Bank. (2011). World development report 2011. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (2018). World governance indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Wulifan, J. K., Brenner, S., Jahn, A., & De Allegri, M. (2016). A scoping review on determinants of unmet need for family planning among women of reproductive age in low and middle income countries. BMC Women’s Health, 16, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0281-3

Yeatman, S., Sennott, C., & Culpepper, S. (2013). Young women’s dynamic family size preferences in the context of transitioning fertility. Demography, 50, 1715–1737.

Zimmerman, F. J., & Carter, M. R. (2003). Asset smoothing, consumption smoothing and the reproduction of inequality under risk and subsistence constraints. Journal of Development Economics, 71, 233–260.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Yosef Bodovski and Matthew Brooks for programming assistance. Thiede acknowledges the assistance provided by the Population Research Institute at Penn State, which is supported by an infrastructure grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD041025). Thiede and Piazza also acknowledge support from the Penn State Social Science Research Institute and the Penn State Center for Security Research and Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study concept and design. Data management, data analysis, and the preparation of the manuscript were led by Brian Thiede with significant contributions from all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and Consent

The authors report no ethical issues.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 50 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thiede, B.C., Hancock, M., Kodouda, A. et al. Exposure to Armed Conflict and Fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Demography 57, 2113–2141 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00923-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00923-2