Abstract

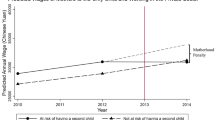

Using North Carolina data for the period 1990–2010, we estimate the effects of economic downturns on the birthrates of 15- to 19-year-olds, using county-level business closings and layoffs as a plausibly exogenous source of variation in the strength of the local economy. We find little effect of job losses on the white teen birthrate. For black teens, however, job losses to 1 % of the working-age population decrease the birthrate by around 2 %. Birth declines start five months after the job loss and then last for more than one year. Linking the timing of job losses and conceptions suggests that black teen births decline because of increased terminations and perhaps also because of changes in prepregnancy behaviors. National data on risk behaviors also provide evidence that black teens reduce sexual activity and increase contraception use in response to job losses. Job losses seven to nine months after conception do not affect teen birthrates, indicating that teens do not anticipate job losses and lending confidence that job losses are “shocks” that can be viewed as quasi-experimental variation. We also find evidence that relatively advantaged black teens disproportionately abort after job losses, implying that the average child born to a black teen in the wake of job loss is relatively more disadvantaged.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the early years of the sample, the Latino population in North Carolina was too small to provide stable county-level measures of teen birthrates. Throughout the article, the terms “white” and “black” are used to refer to non-Hispanic members of those racial groups.

In July 2010, North Carolina instituted a new birth certificate form, with changes in the type and measurement of outcomes, and post-June data are not comparable to pre-June data.

We considered three sources of time-varying measures of county population: decennial census data with linear interpolation used for intercensus years (estimates from the North Carolina Governor’s Office, and Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results estimates from the National Cancer Institute). Each source provided data that correlated above .99 with each other source, and estimates were robust to using any source.

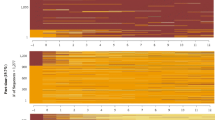

When separate measures for job losses in each of a series of three-month intervals preceding the conception are included in a model, effects for one to three, four to six, and seven to nine months are significant and of similar magnitude, while effects more than nine months prior to conception are small and insignificant; results are presented in Table 8 in the Appendix. For efficiency, we combine job losses for one to nine months into a single measure and do not include job losses for earlier periods in our main specification.

Attempts were made to analyze micro-level North Carolina abortion data; however, these data were missing important demographic indicators in such a high percentage of cases as to render the data unusable. Nationally, both black and white teens have significant abortion rates (Jones et al. 2010).

Authors’ calculations, using data obtained from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (retrieved from http://data.bls.gov).

In other specifications, we considered whether job loss was nonlinearly related to teen fertility by squaring job loss, by logging job loss, and by dividing our continuous measure of job loss into dichotomous categories (e.g., no job loss, .01 to 1 % job loss). We also considered specifications in which the effect of job loss varied by the level of preexisting unemployment. We found little evidence supporting a nonlinear model of the relationship between job losses and teen fertility, or that the effect of job loss varied by levels of preexisting unemployment.

These analyses can be conducted only with Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data, because SEER measures vary nonlinearly within decade, population group, and county. Monthly population counts of teenagers are not available. In other work (Ananat et al. 2011), we estimated the effect of job losses last year on this year’s county public school enrollment for various grades and found no relationship; because those data represent actual counts rather than population estimates, they provide a stronger additional falsification test and lend confidence that endogenous migration is not occurring.

Other measures of disadvantage, such as whether the mother used Medicaid to pay for the birth, are not available until December 2010.

“Mass” is defined as 50 or more workers. BLS does not collect data on layoffs or closings affecting fewer than 50 workers.

State-level estimates of effects of job losses on black and white teen fertility are consistent with our North Carolina estimates. However, because job loss data for other states are provided only quarterly, it is not possible to estimate our models using state-level data.

The miscarriage rate for women is estimated to range from 11 to 12 miscarriages per 1,000 pregnancies (Knudsen et al. 1991; Regan et al. 1989; Warburton and Fraser 1964). Assuming a miscarriage rate of 12 %, then the implied pregnancy rate is 84.2 (based on a birthrate of 74.1 births per 1,000 women and pregnancy rate of 74.1 / (100 – .12), or 84.2 %). A miscarriage rate of 12 % would thus translate into 10.1 losses per 1,000 black teens (82.6 – 74.1); for miscarriage rate of 11 %, 9.2 losses would be found. The observed decrease of more than two births for this group, if caused by increased miscarriage, implies more than a 20 % increase in the miscarriage rate due to job loss.

Immediate changes in funding for community services, however, are unlikely to be responsible for the decrease in teen fertility because effects occur too quickly after job losses to be driven by government or nonprofit funding cycles.

References

Abma, J. C., Martinez, G. M., & Copen, C. E. (2010). Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, National Survey of Family Growth 2006–2008 (Vital and Health Statistics 23(30)). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Ananat, E. O., Francis, D. V., Gassman-Pines, A., & Gibson-Davis, C. (2013). Children left behind: The effects of statewide job loss on student achievement (NBER Working Paper No. 17104). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ananat, E. O., Gassman-Pines, A., & Gibson-Davis, C. (2011). The effects of local employment losses on children’s educational achievement. In G. J. Duncan & R. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality and the uncertain life chances of low-income children (pp. 299–313). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Ananat, E. O., Gruber, J., Levine, P. B., & Staiger, D. (2009). Abortion and selection. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91, 124–136.

Arkes, J., & Klerman, J. A. (2009). Understanding the link between the economy and teenage sexual behavior and fertility outcomes. Journal of Population Economics, 22, 517–536.

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In G. S. Becker (Ed.), Demographic and economic change in developed countries (pp. 209–231). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1976). Child endowments and the quantity of children. Journal of Political Economy, 84, S143–S162.

Betts, J. R., & McFarland, L. L. (1995). Safe port in a storm: The impact of labor market conditions on community college enrollments. Journal of Human Resources, 30, 741–765.

Black, D. A., McKinnish, T. G., & Sanders, S. S. (2005). Tight labor markets and the demand for education: Evidence from the coal boom and bust. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 59, 3–15.

Bongaarts, J., & Feeney, G. (1998). On the quantum and tempo of fertility. Population and Development Review, 24, 271–291.

Buhi, E. R., & Goodson, P. (2007). Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: A theory-guided systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 4–21.

Burton, G. J., & Jauniaux, E. (2004). Placental oxidative stress: From miscarriage to preeclampsia. Reproductive Sciences, 11, 342–352.

Caldwell, C. H., & Antonucci, T. C. (1997). Childbearing during adolescence: Mental health risks and opportunities. In J. Schulenberg, J. L. Maggs, & K. Hurrelmann (Eds.), Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence (pp. 220–245). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Carpenter, C. (2005). Youth alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: Evidence from underage drunk driving laws. Journal of Health Economics, 24, 613–628.

Catalano, R. F., Goldman-Mellor, S., Saxton, K., Margerison-Zilko, C., Subbaraman, M., LeWinn, K., & Anderson, E. (2011). The health effects of economic decline. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 431–450.

Chamberlain, G. (1982). Multivariate regression models for panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 18, 5–45.

Darity, W. A., Jr., & Nicholson, M. J. (2005). Racial wealth inequality and the black family. In V. C. McLoyd, N. E. Hill, & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity (pp. 78–85). New York: The Guilford Press.

Dehejia, R., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2004). Booms, busts, and babies’ health. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 1091–1130.

Fairlie, R. W., & Kletzer, L. G. (1998). Jobs lost, jobs regained: An analysis of black/white differences in job displacement in the 1980s. Industrial Relations, 37, 460–477.

Farber, H. S. (2004). Job loss in the United States, 1981–2001. Research in Labor Economics, 23, 69–117.

Fishback, P. V., Haines, M. R., & Kantor, S. (2007). Births, deaths, and New Deal relief during the Great Depression. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89, 1–14.

Fletcher, J. M. (2007). Social multipliers in sexual initiation decisions among U.S. high school students. Demography, 44, 373–388.

Goddijn, M., & Leschot, N. J. (2000). Genetic aspects of miscarriage. Baillière’s Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 14, 855–865.

Gruber, J., Levine, P., & Staiger, D. (1999). Abortion legalization and child living circumstances: Who is the “marginal child”? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 263–291.

Guiliano, P., & Spilimbergo, A. (2009). Growing up in a recession: Beliefs and the macroeconomy (NBER Working Paper No. 15321). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2010). Births: Preliminary data for 2009 (National Vital Statistics Reports 59(3)). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Jacobson, L. S., LaLonde, R. J., & Sullivan, D. G. (1993). Earnings losses of displaced workers. American Economic Review, 83, 685–709.

Jones, R. K., Finer, L. B., & Singh, S. (2010). Characteristics of U.S. abortion patients, 2008. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

Kearney, M. S., & Levine, P. B. (2012). Why is the teen birth rate in the United States so high and why does it matter? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 141–166.

Kirby, D. (2001a). Emerging answers: Research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy.

Kirby, D. (2001b). Understanding what works and what doesn’t in reducing adolescent sexual risk-taking. Family Planning Perspectives, 33, 276–281.

Kletzer, L. G. (1998). Job displacement. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12, 115–136.

Knudsen, U. B., Hansen, V., Juul, S., & Secher, N. J. (1991). Prognosis of a new pregnancy following previous spontaneous abortions. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, 39, 31–36.

Levine, P. (2001). The sexual activity and birth-control use of American teenagers. In J. Gruber (Ed.), Risky behavior among youths: An economic analysis (pp. 167–217). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Levine, P. (2002). The impact of social policy and economic activity throughout the fertility decision tree (NBER Working Paper No. 9021). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Sutton, P. D., Ventura, S. J., Mathews, T. J., & Osterman, M. J. K. (2010). Births: Final data for 2008 (National Vital Statistics Reports 59). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Ventura, S. J., Osterman, M. J. K., Wilson, E. C., & Mathews, T. J. (2012). Births: Final data for 2010 (National Vital Statistics Reports 60(2)). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Martinez, G., & Copen, C. E. (2010). Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, National Survey of Family Growth 2006–2008 (Vital Health Statistics 23(30)). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2011). Counting it up: The public costs of teen childbearing. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy.

Regan, L., Braude, P. R., & Trembath, P. L. (1989). Influence of past reproductive performance on risk of spontaneous abortion. British Medical Journal, 299, 541–545.

Regan, L., & Rai, R. (2000). Epidemiology and the medical causes of miscarriage. Baillière's Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 14, 839–854.

Rindfuss, R. R., Morgan, S. P., & Swicegood, G. (1988). First births in America: Changes in the timing of parenthood. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schaller, J. (2012). Booms, busts, and fertility: Testing the Becker model using gender-specific labor demand. Davis: University of California–Davis.

Stevens, A. H. (1997). Persistent effects of job displacement: The importance of multiple job losses. Journal of Labor Economics, 15, 165–188.

Vesely, S. K., Wyatt, V. H., Oman, R. F., Aspy, C. B., Keglerd, M. C., Rodine, S., & McLeroy, K. R. (2004). The potential protective effects of youth assets from adolescent sexual risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34, 356–365.

Warburton, D., & Fraser, F. C. (1964). Spontaneous abortion risks in man: Data from reproductive histories collected in a medical genetics unit. American Journal of Human Genetics, 16, 1–25.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eric Bannister, Dania Francis, Matthew Panhans, and Megan Reynolds for their outstanding research assistance. They gratefully acknowledge the support of the Smith Richardson Foundation; Ananat and Gibson-Davis gratefully acknowledge the support of the William T. Grant Foundation; and Gassman-Pines gratefully acknowledges the support of Foundation for Child Development. Helpful feedback on this article was provided by seminar participants at the University of California–Davis Economics Department; meeting participants at the Population Association of America; and members of the Beyond Test Scores research team at Duke University, especially Charlie Clotfelter, Phil Cook, Ken Dodge, Helen Ladd, and Jake Vigdor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors listed alphabetically to denote equal contributions.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ananat, E.O., Gassman-Pines, A. & Gibson-Davis, C. Community-Wide Job Loss and Teenage Fertility: Evidence From North Carolina. Demography 50, 2151–2171 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0231-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0231-3