Abstract

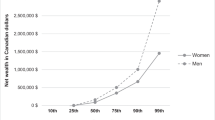

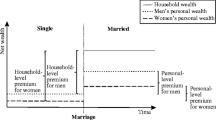

To assess and explain the United States’ gender wealth gap, we use the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study to examine wealth accumulated by a single cohort over 50 years by gender, by marital status, and limited to the respondents who are their family’s best financial reporters. We find large gender wealth gaps between currently married men and women, and between never-married men and women. The never-married accumulate less wealth than the currently married, and there is a marital disruption cost to wealth accumulation. The status-attainment model shows the most power in explaining gender wealth gaps between these groups explaining about one-third to one-half of the gap, followed by the human-capital explanation. In other words, a lifetime of lower earnings for women translates into greatly reduced wealth accumulation. After controlling for the full model, we find that a gender wealth gap remains between married men and women that we speculate may be related to gender differences in investment strategies and selection effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Other tables that include the non-BFR are available from the lead author by request.

References

Anderson, J. M. (1999). The wealth of U.S. families: Analysis of recent census data. Chevy Chase, MD: Capital Research Associates.

Bajtelsmit, V. L., & Bernasek, A. (1996). Why do women invest differently than men? Financial Counseling and Planning, 7, 1–10.

Bernheim, B. D., & Garrett, D. M. (2003). The effects of financial education on the workplace: Evidence from a survey of households. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 1487–1519.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2007). The gender pay gap. Economists’ Voice, 4(4), 5.

Blau, P. M., & Duncan, O. D. (1967). The American occupational structure. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Chand, H., & Gan, L. (2003). The effects of bracketing in wealth estimation. The Review of Income and Wealth, 49, 273–287.

Cox, D. (2003). Private transfers within the family: Mothers, fathers, sons and daughters. In A. H. Munnell & A. Sunden (Eds.), Death and dollars: The role of gifts and bequests in America (pp. 168–216). Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Deere, C. D., & Doss, C. R. (2006). The gender asset gap: What do we know and why does it matter. Feminist Economics, 12(1–2), 1–50.

Denton, M., & Boos, L. (2007). The gender wealth gap: Structural and material constraints and implications for later life. Journal of Women & Aging, 19, 105–119.

Dietz, B. E., Carrozza, M., & Ritchey, P. N. (2003). Does financial self-efficacy explain gender differences in retirement saving strategies? Journal of Women & Aging, 15, 83–96.

Duncan, O. D., Featherman, D. L., & Duncan, B. (1972). Socioeconomic background and achievement. New York: Seminar Press.

Elder, H. W., & Rudolph, P. M. (2003). Who makes the financial decisions in the households of older Americans? Financial Services Review, 12, 293–308.

Gale, W. G., & Scholz, J. K. (1994). Intergenerational transfers and the accumulation of wealth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8, 145–160.

Gibson, J., Le, T., & Scobie, G. (2006). Household bargaining over wealth and the adequacy of women’s retirement incomes in New Zealand. Feminist Economics, 12, 221–246.

Ginn, J., & Arbor, S. (1996). Patterns of employment, gender and pensions: The effect of work history on older women’s non-state pensions. Work, Employment and Society, 10, 469–490.

Grinstein-Weiss, M., Yeo, Y. H., Zhan, M., & Pajarita, C. (2008). Asset holding and net worth among households with children: Differences by household type. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 62–78.

Hanna, S. D., & Lindamood, S. (2005, October). Risk tolerance of married couples. Paper presented at the meeting of the Academy of Financial Services, Chicago, IL.

Hardy, M. A., & Shuey, K. (2000). Pension decisions in a changing economy: Gender structure, and choice. Journal of Gerontology, Social Sciences, 55, S271–S277.

Hauser, R. M., & Willis, R. J. (2005). Survey design and methodology in the health and retirement study and the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. In L. J. Waite (Ed.), Aging, health, and public policy: Demographic and economic perspectives (pp. 209–235). New York: Population Council.

Henmon, V. A. C., & Nelson, M. J. (1954). The Henmon-Nelson tests of mental ability. Manual for administration. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin.

Hurd, M. D. (1999). Anchoring and acquiescence bias in measuring assets in household surveys. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19, 111–136.

Hurd, M. D., & Rodgers, W. (1998). The effects of bracketing and anchoring on measurement in the health and retirement study. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Kapteyn, A., Alessie, R., & Lusardi, A. (2005). Explaining the wealth holdings of different cohorts: Productivity growth and social security. European Economic Review, 49, 1361–1391.

Land, K. C. (1996). Wealth accumulation across the adult life course: Stability and change in sociodemographic covariate structures of net worth data in the survey of income and program participation, 1984–1999. Social Science Research, 25, 426–462.

Lindamood, S., & Hanna, S. D. (2005, October). Determinants of the wife being the financially knowledgeable spouse. Paper presented at the Academy of Financial Services Meeting, Chicago, IL.

Marini, M. M. (1978). The transition to adulthood: Sex differences in educational attainment and age at marriage. American Sociological Review, 43, 483–507.

Marini, M. M. (1989). Sex differences in earnings in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 15, 343–380.

Ozawa, M. N., & Lee, Y. (2006). The net worth of female-headed households: A comparison to other types of households. Family Relations, 55, 132–145.

Ozawa, M. N., & Lum, Y. S. (2001). Taking risks in investing in the equity market: Racial and ethnic differences. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 12, 1–12.

Rodgers, W. L., & Thornton, A. (1985). Changing patterns of first marriage in the United States. Demography, 22, 265–279.

Ruel, E., & Hauser, R. M. (2007). Gender, education and wealth: A prospective study (CDE Working Paper 2007–003). Madison: Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Schmidt, L., & Sevak, P. (2006). Gender, marriage, and asset accumulation in the United States. Feminist Economics, 12, 139–166.

Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., & Ohlendorf, G. W. (1970). The educational and early occupational status attainment process: Replication and revision. American Sociological Review, 35, 1014–1027.

Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., & Portes, A. (1969). The educational and early occupational attainment process. American Sociological Review, 34, 82–92.

Sewell, W. H., Hauser, R. M., Springer, K. W., & Hauser, T. S. (2004). As we age: The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, 1957–2001. In K. Leicht (Ed.), Research in social stratification and mobility (Vol. 20, pp. 3–111). London, UK: Elsevier.

Sierminska, E. M., Fricky, J. R., & Grabka, M. M. (2010). Examining the gender wealth gap. Oxford Economic Papers, 62, 669–690.

Sunden, A. E., & Surette, B. (1998). Gender differences in the allocation of assets in investment savings plans. The American Economic Review, 88, 207–211.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2001). Household net worth and asset ownership, 1995 (No. 70–71). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration.

Warren, T., Rowlingson, K., & Whyley, C. (2001). Female finances: Gender wage gaps and gender asset gaps. Work, Employment and Society, 15, 465–488.

Warren, J. R., Sheridan, J. T., & Hauser, R. M. (1998). Choosing a measure of occupational standing: How useful are composite measures in analyses of gender inequality in occupational attainment? Sociological Methods & Research, 27, 3–76.

Watson, J., & McNaughton, M. (2007). Gender differences in risk aversion and expected retirement benefits. Financial Analysts Journal, 63(4), 52–62.

Wilmoth, J., & Koso, G. (2002). Does marital history matter? Marital status and wealth outcomes among preretirement adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 254–268.

Wolff, E. N. (2000). Recent trends in the size distribution of household wealth (Working Paper No. 300). Annandale-on Hudson, NY: Bard College, Jerome Levy Economics Institute.

Yamokoski, A., & Keister, L. A. (2006). The wealth of single women: Marital status and parenthood in the asset accumulation of young baby boomers in the United States. Feminist Economics, 12(1–2), 167–194.

Yuan, Y. C. (2000). Multiple imputation for missing data: Concepts and new development (SAS Paper P267–25). Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dawn Baunach and Meredith Greif for commenting on an early draft of this article. The research reported herein was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG-9775, P01-AG21079 and T32-AG00129), by the William Vilas Estate Trust, and by the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ruel, E., Hauser, R.M. Explaining the Gender Wealth Gap. Demography 50, 1155–1176 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0182-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0182-0