Abstract

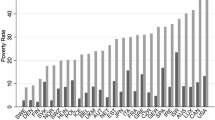

We examine the influence of individual characteristics and targeted and universal social policy on single-mother poverty with a multilevel analysis across 18 affluent Western democracies. Although single mothers are disproportionately poor in all countries, there is even more cross-national variation in single-mother poverty than in poverty among the overall population. By far, the United States has the highest rate of poverty among single mothers among affluent democracies. The analyses show that single-mother poverty is a function of the household’s employment, education, and age composition, and the presence of other adults in the household. Beyond individual characteristics, social policy exerts substantial influence on single-mother poverty. We find that two measures of universal social policy significantly reduce single-mother poverty. However, one measure of targeted social policy does not have significant effects, and another measure is significantly negative only when controlling for universal social policy. Moreover, the effects of universal social policy are larger. Additional analyses show that universal social policy does not have counterproductive consequences in terms of family structure or employment, while the results are less clear for targeted social policy. Although debates often focus on altering the behavior or characteristics of single mothers, welfare universalism could be an even more effective anti-poverty strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We code couples using the variable “married,” which includes married and nonmarried cohabiting couples (including same-sex couples). Unfortunately, the LIS does not provide sufficient information to identify the mother of the children. So, our sample includes other 18- to 54-year-old women residing in the household. We address this problem by controlling for other adults and multiple earners in the household and by estimating the models on lone mothers. Although Rainwater and Smeeding (2004:109–110) defined single-mother households simply as female-headed households with children present, we employ an even more stringent definition by including only those not married or cohabiting.

DPI includes disposable cash and noncash income after taxes and transfers (including food stamps; housing allowances; and tax credits, such as the EITC).

The categories are (a) less than secondary (low), (b) secondary or some tertiary (medium), and (c) completed tertiary or more (high). Unfortunately, the LIS does not provide sufficient detail to code vocational/technical secondary education.

In analyses available upon request, we variously add head of household’s age-squared, age of the respondent, and dummy variables for the respondent or head being under age 25. The results are consistent.

Slightly more than one-third of the sample has a child under 5, and the average single-mother household has 1.7 children (see Table 1). We define targeted benefits for a mother with a child under 3 because this maximizes the value of targeted benefits, giving this measure the best chance of being consequential (i.e., countries usually give greater benefits for young children). One could construct alternative single-mother entitlement rates for various numbers and ages of children; however, it is difficult to reduce these to one estimate per country.

For the United States, this is the mean benefit of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) across states. One could include the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program. However, we were unable to identify any cross-national source on means-tested in-kind benefits. We did not include food stamps and/or housing assistance because those are means-tested for all and not targeted for single mothers. Adding in-kind benefits in the United States would only raise the already above-average single-mother entitlement and thus would lead to an even less significant effect (cf. Tables 2 and 3).

We use the term “nonemployed” to make clear that we do not include unemployment benefits here. Although a nonemployed single mother might qualify for unemployment benefits, this is not a benefit targeted at single mothers. (It is targeted at the unemployed.) Moreover, many single mothers have not been previously employed long enough to qualify for unemployment insurance.

“Total government assistance” sums social insurance, social assistance transfers, alimony, and child support. To equivalize this measure, we divide by the square root of household members. We tested several derivations of this measure, and the results are robust (e.g., concentrating on social assistance targeted to low-income households and adding or subtracting social insurance, alimony/child support, child/family benefits, unemployment compensation, and maternity/family leave benefits). We present the comprehensive measure because there is often targeting implicit in what are statutorily considered universal programs.

Yet another alternative would measure the mean total government assistance received by single mothers (in each country standardized over the median) that is not received by the general population. This “absolute” measure of targeted benefits would be the difference between what the target group and general population receive. In analyses available upon request, this produces results nearly identical to the targeting ratio.

In analyses available upon request, we substitute each of these indicators as well some alternatives (e.g., family assistance as percentage of GDP). The results are consistent. Also, there is no evidence of significant interaction effects of our welfare state measures with welfare regimes or of regime main effects.

We also include the Ns for each country. Please note that a few countries have samples of fewer than 200 cases. For these (e.g., the Netherlands), the mean level of single-mother poverty should be read with caution.

The single-mother entitlement is calculated as a percent of median equivalized household income, and poverty is defined as less than 50% of median equivalized household income. Thus, France is the only country with a value higher than 50%.

For both Italy and Spain, the single-mother entitlement is 0. Both provide family assistance only as a supplement to employment earnings. For example, a single mother in Italy is eligible for family assistance if she is employed, the only wage earner in the family, and low-income. As explained in the Methods section, this measure assumes nonemployment, following the argument that this benefit is solely for being a mother with young children.

Even though unemployment was significant in Models 1 and 2, both economic context variables would be insignificant if included, and the other results would be consistent.

These models are intentionally parsimonious, including only a few individual-level controls. The results are not sensitive to the inclusion of other individual-level controls. Although we include both social policy measures in the same models, the results are robust if modeled separately. The first four are multilevel logit models, and the last is a multilevel Poisson model.

Although not shown, the welfare state index would be negatively signed and insignificant, and the single-mother entitlement would be positively signed and insignificant. As shown in Table 6, the universal replacement rate is negatively signed and insignificant for lone motherhood as well.

References

Ananat, E. O., & Michaels, G. (2008). The effect of marital breakup on the income and poverty of women with children. Journal of Human Resources, 43, 611–629.

Bane, M. J., & Ellwood, D. T. (1994). Welfare realities: From rhetoric to reform. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barry, B. (1990). The welfare state versus the relief of poverty. Ethics, 100, 503–529.

Barth, M. C., Cargano, G. J., & Palmer, J. L. (1974). Toward an effective income support system: Problems, prospects, and choices. Madison: University of Wisconsin, Institute for Research on Poverty.

Behrendt, C. (2000). Do means-tested benefits alleviate poverty? Evidence on Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom from the Luxembourg Income Study. Journal of European Social Policy, 10, 23–41.

Besley, T. (1990). Means testing versus universal provision in poverty alleviation programmes. Economica, 57, 119–129.

Bianchi, S. M. (1999). Feminization and juvenilization of poverty: Trends, relative risks, causes, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 307–333.

Blank, R. M. (1997). It takes a nation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Blau, F. D., Kahn, L. M., & Waldfogel, J. (2004). The impact of welfare benefits on single motherhood and headship of young women: Evidence from the census. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 382–404.

Brady, D. (2003). Rethinking the sociological measurement of poverty. Social Forces, 81, 715–752.

Brady, D. (2009). Rich democracies, poor people: How politics explain poverty. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brady, D., Fullerton, A., & Moren-Cross, J. (2009). Putting poverty in political context: A multi-level analysis of adult poverty across 18 affluent Western democracies. Social Forces, 88, 271–300.

Brady, D., & Kall, D. (2008). Nearly universal, but somewhat distinct: The feminization of poverty in affluent Western democracies, 1969–2000. Social Science Research, 37, 976–1007.

Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2007). Why welfare states persist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Carlson, M., Garfinkel, I., McLanahan, S., Mincy, R., & Primus, W. (2004). The effects of welfare and child support policies on union formation. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 513–542.

Chen, W.-H., & Corak, M. (2008). Child poverty and changes in child poverty. Demography, 45, 537–553.

Christopher, K. (2002). Welfare state regimes and mothers’ poverty. Social Politics, 9, 60–86.

Christopher, K., England, P., Smeeding, T. M., & Ross, K. (2002). The gender gap in poverty in modern nations: Single motherhood, the market, and the state. Sociological Perspectives, 45, 219–242.

Collier, P., & Dollar, D. (2001). Can the world cut poverty in half? How policy reform and effective aid can meet international development goals. World Development, 29, 1787–1802.

Creedy, J. (1996). Comparing tax and transfer systems: Poverty, inequality and target efficiency. Economica, 63, S163–S174.

Currie, J. (2006). The take-up of social benefits. In A. J. Auerbach, D. Card, & J. M. Quigley (Eds.), Public policy and the income distribution (pp. 80–148). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

DeFina, R. H., & Thanawala, K. (2003). International evidence on the impact of taxes and transfers on alternative poverty indexes. Social Science Research, 33, 322–338.

Edin, K., & Lein, L. (1997). Making ends meet. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindustrial economies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fitzgerald, J. M., & Ribar, D. C. (2004). Welfare reform and female headship. Demography, 41, 189–212.

Garfinkel, I., & McLanahan, S. S. (1986). Single mothers and their children: A new American dilemma. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Gilbert, N. (2002). Transformation of the welfare state: The silent surrender of public responsibility. New York: Oxford University Press.

Goodin, R. E., & Le Grand, J. (1987). Not only the poor. London, UK: Allen and Unwin.

Gornick, J. (2004). Women’s economic outcomes, gender inequality and public policy: Findings from the Luxembourg Income Study. Socio-Economic Review, 2, 213–238.

Greenstein, R. (1991). Universal and targeted approaches to relieving poverty: An alternative view. In C. Jencks & P. E. Peterson (Eds.), The urban underclass (pp. 437–459). Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Gundersen, C., & Ziliak, J. P. (2004). Poverty and macroeconomic performance across space, race, and family structure. Demography, 41, 61–86.

Handler, J. F., & Hasenfeld, Y. (2007). Blame welfare, ignore poverty and inequality. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Heuveline, P., & Weinshenker, M. (2008). The international child poverty gap: Does demography matter? Demography, 45, 173–191.

Hicks, A. (1999). Social democracy and welfare capitalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Huber, E., & Stephens, D. (2001). Development and crisis of the welfare state. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Huber, E., Stephens, J. D., Bradley, D., Moller, S., & Nielsen, F. (2009). The politics of women’s economic independence. Social Politics, 16, 1–39.

Huber, E., Stephens, J. D., Ragin, C., Brady, D., & Beckfield, J. (2004). Comparative welfare states data set. University of North Carolina, Northwestern University, Duke University, and Indiana University.

Kakwani, N., & Subbarao, K. (2007). Poverty among the elderly in sub-Saharan Africa and the role of social pensions. Journal of Development Studies, 43, 987–1008.

Kamerman, S. B. (1995). Gender role and family structure changes in the advanced industrialized West: Implications for social policy. In K. McFate, R. Lawson, & W. J. Wilson (Eds.), Poverty, inequality, and the future of social policy (pp. 231–256). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kilkey, M., & Bradshaw, J. (1999). Lone mothers, economic well-being, and policies. In D. Sainsbury (Ed.), Gender and welfare state regimes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the Western countries. American Sociological Review, 63, 661–687.

Krishna, A. (2007). For reducing poverty faster: Target reasons before people. World Development, 35, 1947–1960.

Le Grand, J. (1982). The strategy of equality: Redistribution and the social services. London, UK: George Allen and Unwin.

Leisering, L., & Leibfried, S. (1999). Time and poverty in Western welfare states: United Germany in perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lichter, D. T., McLaughlin, D. K., & Ribar, D. C. (1997). Welfare and the rise of female-headed families. The American Journal of Sociology, 103, 112–143.

Lichter, D. T., Qian, Z., & Mellott, L. M. (2006). Marriage or dissolution? Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography, 43, 223–240.

Lindbeck, A. (1998). The welfare state and the employment problem. American Economic Review, 84, 71–75.

Lindert, P. H. (2004). Growing public (Vol. I). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database (n.d.). [Data file, multiple countries; analyses based on data available December 2009]. Luxembourg: LIS. Retrieved from http://www.lisdatacenter.org

Mahler, V. A., & Jesuit, D. K. (2006). Fiscal redistribution in the developed countries: New insights from the Luxembourg Income Study. Socio-Economic Review, 4, 483–511.

Martin, M. A. (2006). Family structure and income inequality in families with children, 1976 to 2000. Demography, 43, 421–445.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

Mead, L. M. (1986). Beyond entitlement. New York: Free Press.

Misra, J. (2002). Class, race, and gender and theorizing welfare states. Research in Political Sociology, 11, 19–52.

Misra, J., Moller, S., & Budig, M. J. (2007). Work-family policies for partnered and single women in Europe and North America. Gender and Society, 21, 804–827.

Moffitt, R. (2000). Welfare benefits and female headship in U.S. time series. American Economic Review, 90, 373–377.

Moller, S., Bradley, D., Huber, E., Nielsen, F., & Stephens, J. D. (2003). Determinants of relative poverty in advanced capitalist democracies. American Sociological Review, 68, 22–51.

Musick, K. A., & Mare, R. D. (2004). Family structure, intergenerational mobility, and the reproduction of poverty: Evidence for increasing polarization? Demography, 41, 629–648.

Nelson, K. (2004). Mechanisms of poverty alleviation. Journal of European Social Policy, 14, 371–390.

Nelson, K. (2007). Universalism versus targeting: The vulnerability of social insurance and means-tested minimum income protection in 18 countries, 1990–2002. International Social Security Review, 60, 33–58.

Orloff, A. (1993). Gender and the social rights of citizenship: The comparative analysis of gender relations and welfare states. American Sociological Review, 58, 303–328.

Piven, F. F., & Cloward, R. A. (1993). Regulating the poor. New York: Vintage.

Rainwater, L., & Smeeding, T. M. (2004). Poor kids in a rich country. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Rank, M. R. (2005). One nation, underprivileged. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rose, R. (1995). Lone parents: The Canadian experience. In K. McFate, R. Lawson, & W. J. Wilson (Eds.), Poverty, inequality and the future of social policy (pp. 327–366). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sainsbury, D. (1999). Gender and welfare state regimes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schellekens, J. (2009). Family allowances and fertility: Socioeconomic differences. Demography, 46, 451–468.

Seccombe, K. (2000). Families in poverty in the 1990s: Trends, causes, consequences, and lessons learned. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1094–1113.

Sefton, T. (2006). Distributive and redistributive policy. In M. Moran, M. Rein, & R. E. Goodin (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public policy (pp. 607–623). New York: Oxford University Press.

Sidel, R. (2006). Unsung heroines: Single mothers and the American dream. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Skocpol, T. (1991). Targeting within universalism: Politically viable policies to combat poverty in the United States. In C. Jencks & P. E. Peterson (Eds.), The urban underclass (pp. 411–436). Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Skocpol, T. (1992). Protecting soldiers and mothers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smeeding, T. (2006). Poor people in rich nations: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 69–90.

Sorensen, A. (1994). Women’s economic risk and the economic position of single mothers. European Sociological Review, 10, 173–188.

Squire, L. (1993). Fighting poverty. American Economic Review, 83, 377–382.

Thomas, A., & Sawhill, I. (2002). For richer or for poorer: Marriage as an anti-poverty strategy. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 21, 587–599.

Tullock, G. (1997). Economics of income redistribution (2nd ed.). Norwell, MA: Kluwer.

Whitehead, M., Burstrom, B., & Diderichsen, F. (2000). Social policies and the pathways to inequalities in health: A comparative analysis of lone mothers in Britain and Sweden. Social Science & Medicine, 50, 255–270.

Wilensky, H. L. (2002). Rich democracies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wilson, W. J. (1996). When work disappears. New York: Norton.

Wu, L. L. (2008). Cohort estimates of nonmarital fertility for U.S. women. Demography, 45, 193–207.

Zuberi, D. (2006). Differences that matter. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Acknowledgments

We thank Demography reviewers, guest editor Suzanne Bianchi, editor Stewart Tolnay, as well as Liz Ananat, Lane Destro, Andrew Fullerton, Bob Jackson, Stephanie Moller, Jennifer Moren Cross, Stephen Morgan, Emilia Niskanen, and David Reingold for assistance and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Online Resource 1

Targeting, Universalism, and Single-Mother Poverty: A Multilevel Analysis Across 18 Affluent Democracies David Brady and Rebekah Burroway (DOCX 76 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brady, D., Burroway, R. Targeting, Universalism, and Single-Mother Poverty: A Multilevel Analysis Across 18 Affluent Democracies. Demography 49, 719–746 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0094-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0094-z