Abstract

This paper is to inform the recent situations of work by the foreign domestic workers (FDWs) in Hong Kong through the lens of Covid-19. Through the interviews with seven informants — two employers and five FDWs, stories describing the changes in their working conditions, rights and entitlement, and the contextual environment related to the impacts of Covid-19 were collected. They were analysed through three theoretical tools — visibility/invisibility, mobility/immobility, and work boundary. The findings show that under the Covid-19 crisis, the FDWs experienced more hardships and struggles in both the home country and host country. The paradoxes of visibility/invisibility and mobility/immobility together with blurred work boundary were found in their experience of work, rights and entitlement, and the contextual environment. On one hand, the employers’ power of controlling FDWs has increased, but the agency to resist by the FDWs has decreased making them to turn to more passive means of resistance which could harm the FDWs’ physical and mental health and wellbeing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The outbreak of Covid-19 has affected the foreign domestic workers (FDWs) who have been contributing to the Hong Kong economy. Hong Kong has one of the highest densities of FDWs in the world (Huang & Yeung, 2018) with an average of one FDW for every eight households, and one for every three in households with children (Hong Kong Census Statistics Department, 2019). The nature of employment is unique as all FDWs are required to live-in (work and reside) employer’s residence. Covid-19 has forced some employers to work from home (WFH) which has in turn increased the face-to-face interactions between the FDWs and their employers. This study is to investigate the impacts of Covid-19–induced changes on FDWs’ work and livelihood at the home and host country. Although numerous researches have been done on FDWs worldwide and Hong Kong (Amnesty International, 2020; Bern, 2004; Constable, 2009; Groves & Lui, 2012; Huang et al., 2015; ILO, 2010), current understanding of how Covid-19 has disrupted FDWs’ ordinary livelihood is insufficient and needs to be studied systematically.

This paper reports a qualitative investigation into the experiences of nine FDWs who provided their personal accounts of the changing demands of work and work-related environment, and how they felt and responded to their changes during the pandemic. This paper intends to unfold the impacts of Covid-19 on the FDWs in both home and host country which has largely not been examined.

Literature review

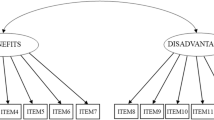

Existing literature reported that FDWs faced many inequalities (In, 2016; Siu, 2018; Yu, 2016); it is expected that Covid-19 would aggravate the inequalities. From early to mid-March, the Asian Migrants Coordinating Body conducted a survey of 1127 FDWs, and the results disclosed that 40% of FDWs reported having their labour rights curtailed over February 2020 due to Covid-19 outbreak (Wong, 2020). The legal requirements stipulated in the FDWs’ employment contract — live in and 2-week rule (requiring leaving Hong Kong in 2 weeks once terminated) have been reported as the major causes for the deprivation of FDWs’ human rights (Cheung et al., 2017). This research analysed these impacts by three theoretical tools visibility/invisibility (Arat-koç, 2012; Brush & Vasupuram, 2006; Scotland-Stewart, 2007), mobility/immobility (Cook & Butz, 2016, 2018; Dobusch & Kreissl, 2020; Elliot & Urry, 2010), and boundary work (Lamont, 1992; Lan, 2003b, 2006; Nippert-Eng, 1995).

Methodology

This paper used a qualitative research methodology.

Data collection and participants

Two FDW personal acquaintances — one each from the Philippines and Indonesia were invited to interview. After that, they were asked to introduce their friends who either intended to work or were working for dual income households with children. Through their network, snowball sampling was employed (Goodman, 1961), and a total of nine female participants (5 Filipinos and 4 Indonesians) were obtained. Table 1 reports their demographic profile.

The data was collected via one-to-one interviews during the period between February and June 2020 by audio-conferencing meetings because of social distancing measures. English was used in all interviews, and each interview lasted for 1 to 1.5 h. The interviews followed an interview protocol covered three aspects: demographic data, changes experienced in environments and work after Covid-19 in home country and host country, and impacts on their work and livelihood. Phenomenological approach (Conklin, 2007; Creswell, 2013) was adopted to engage participants to tell critical incidents/stories about their personal experiences (Boje, 2001; Gabriel, 2000) so as to achieve rich illustrative accounts (Bitner et al., 1994). Due to the sensitivity of the subject matter and confidentiality, the FDWs’ employers mentioned in the interviews were not used for corroborative evidence. An open-ended and probing questioning strategy was implemented to facilitate full, descriptive narratives for each critical incident (Miles et al., 2020). Two to three stories were acquired from each interview. Prior to the interviews, the researcher sought ethical approval from all participants who gave their explicit consent to be interviewed and recorded anonymously. They were reassured about confidentiality, and this report uses pseudonyms to maintain the confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Since the raw data consisted participants’ stories which were subjective rather than objective measurements, the researcher did not judge if the stories were “true” reflections of reality during data analysis (Gabriel, 1995; Spiegelberg, 1978). Since the stories could also manifest “culturally-shaped notions in terms of which people organised their views of themselves, others, and the world in which they live” (Bruner, 1990: 137), data analysis employed a process explication (Conklin, 2007) in which “researchers attend to their awareness, feelings, thoughts, beliefs, and judgments as a prelude to the understanding that is derived from conversations and dialogues with others” (Brisola & Cury, 2016).

The data analysis obtained categories, and consistent comparisons were engaged between the stories and the categories and subcategories. A repeated re-categorisation of the various aspects of each story was conducted until consistency and accuracy of the analysis were achieved to the point of theoretical saturation (Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

Results

Two major types of findings were solicited from the interviews. The first type involved the participants’ experiences, encounters, and perceived impacts of Covid-19 in their home country. The second type entailed the changes of work demand, working environment, and perceived impacts of Covid-19 they experienced in the host country of Hong Kong.

Home country

There were three categories of FDWs, namely the departing FDWs to the host country which comprised of those had already been employed in Hong Kong, and those new ones who had not been employed. Another category was the returning FDWs from Hong Kong back home.

Travel restriction

At the beginning of Covid-19 pandemic, the departing FDWs were restricted by their home country from travelling to Hong Kong. It was estimated that there were around 10,000 Filipinos waiting to return to Hong Kong from the Philippines in January after Chinese New Year holiday (Progressive Labour Union of Domestic Workers in Hong Kong, 2020). When the travel ban was lifted in February, many stranded Filipino FDWs were confused by the Filipino government about the request to sign written declarations to indicate they went back to Hong Kong at their own risk instead of receiving clear precautionary arrangements for their return (Carvalho et al. 2020). Below is the quote from F2’s description of her story:

I am stranded in Manila as I can’t fly back Hong Kong. I have no income but have to pay for the accommodation. I have almost used up all my money after two weeks. My employer SMS me saying that if I can’t go back soon, she will find an Indonesian to replace me. I’m living in constant fear for losing my job as my family depends on my salary. I guess I have to sign whatever given to me as long as I can go back Hong Kong to work.

The Covid-19 had caused immobility (Enrich, 2019) of the FDWs by delaying them from going back to work, which also plunged them into financial difficulties and threatened their family’s livelihood. The travel restrictions could be linked to inequalities as those who refused to sign the risk declarations were prohibited from going back Hong Kong. The immobility reinforced the already inequality regimes based on social class, gender, and migration relations, thereby the FDWs were perceived as less valued and potentially disposable (Dobusch & Kreissl, 2020). This in turn continued to embody FDWs as “production agents” (De Janvry & Garramon, 1977: 214).

The lockdown at the home country

The mobility of the returning Filipino FDWs became restricted again in mid-March when the Philippines government imposed Manila lockdown. Many Filipino FDWs had already planned to return home during Easter holiday but had to cancel their flights (Carvalho, 2020). The story of F1 illustrates how the lockdown hampered her mobility and affected her emotional wellbeing:

I have booked my flight back. However, the lockdown in Manila means I can’t go back home to see my family because all domestic land, sea, and air travel to and from Manila are stopped. I live in a remote island which is only connected by a ferry from Manila. You know, Easter is a family celebration and I really miss my family. I try to remit some money back home, but the lockdown may cause difficulty for them to receive it because the banks and remittance centres are closed. I worry my children will go hungry when they have no money, and I feel so sad that I spend every evening crying quietly.

The consequences of the Manila lockdown had triggered fear, anxiety, and depression among FDWs, and the immobility of both the FDWs and their money could endanger the finance of their families. F1’s worry demonstrates that the FDWs were burdened with gendered responsibilities for their own families at home. The simultaneous occupancy of paid domestic labour in Hong Kong and unpaid labour at home is segmented into distinct spatial settings which underscores FDWs’ agency in their bargain with both monetary and emotional value of their labour (Lan, 2003a).

New FDWs also faced immobility since their application of new employment contracts was stalled by the government agencies (Ranada, 2020). Jakarta, Indonesia, also faced lockdown in April (Listiyorini, 2020). Story of I2 demonstrates how her immobility as a result of Jakarta lockdown was exploited by her employment agency:

I go to Jakarta to look for a new job as FDW. I have to borrow money to pay for the employment agency. When I arrive at Jakarta, I stay in a training centre to learn to speak Cantonese and how to cook Chinese food. The costs of residence and training fee are expensive. I expect to pass the training test and can go to Hong Kong when my travel and employment documents are available around mid-April. However, the Jakarta lockdown has made me stuck in Jakarta for more than 2 months until late May. During the lockdown, my supervisor intentionally made me fail in my training tests three times, so I have to pay more money to them. I have to borrow more money to pay for the training and boarding fees, and I have incurred a huge amount of loans.

The uncertain and unpredictable situations during Covid-19 pandemic had plunged many FDWs, especially those who had no work experiences, into the traps of financial exploitation by the employment agencies.

In sum, home country’s intention to contain Covid-19 had paradoxically produced significant forms of involuntary immobility among the FDWs, and this extreme form of immobility created by travel restriction, lockdown, and quarantine had downgraded the FDWs’ agency against the exploitation by the employment agencies and the employers. Even after the lockdown ended, the FDWs would not be able to resume their normal self (Sutrisno, 2020). It is because the forced immobility on FDWs as a result of Covid-19 not only had caused them financial difficulties but also effected their emotional wellbeing.

Apart from the constraints faced in their home country, FDWs also faced changes in work in the host country which is examined in the next session.

Host country

To prevent the spread of Covid-19, the Hong Kong government enforced WFH and school suspension, creating a full house when all family members stayed at home. This had created negative impacts of increasing conflicts between FDWs and their employers, and FDWs’ workload.

Worsening working condition

Before the Covid-19, most FDWs working for the dual income nuclear families used to have a certain amount of free time and space of their own when their employers were working in office and children were at school. However, the pandemic had eroded their freedom as F5 recounted on the changes of her daily work routine:

I used to have some time on my own between 8am to 3pm when my employer’s kid was in school. As long as I could finish all the household chores, I could call my family when nobody was at home. I could even facetime my friends when I finished my work early. My employer didn’t border me too much as long as I could make her home tidy. I also enjoyed my time waiting outside the school gate because I could talk to other helpers.

However, since the Covid-19, every family member is at home. I have lost all my free time, my employer is constantly inspecting my work, and I have to give up my room to her son after he came back for the UK lockdown. Since then, I have to sleep in the kitchen, and I have lost touch with my family and friends as my employer isn’t happy to see me using my phone. My family isn’t happy as I can’t call them which has made me very sad. I can’t do anything apart from crying secretly in the evening when I can’t sleep. I feel like I’m living in a prison cell because my employer checks on my work and told me follow her Chinese work styles.

The social distancing measures such as WFH have caused a paradoxical effect on FDWs in terms of home space utilisation — the full house had resulted in closer contacts and more frequent interaction between FWDs and employers than before Covid-19 because of the live-in requirement. The impacts of Covid-19 include first, FDWs experienced a decrease in the quality of space and privacy in their workplace/home. Since the FDWs’ social boundary between workplace and home was blurred, they needed to constantly negotiate the socio-spatial boundaries segregating the private and public spheres (Lamont, 1992; Nippert-Eng, 1995). The public social distancing measures had ended up causing an opposite effect on social distancing at the private home space (the workplace of FDWs), and the FDWs’ privacy had been invaded. The socio-categorical boundaries had become more obvious along the divides of class and ethnicity/nationality between the employer and the employee (Lan, 2003a). The pandemic-induced increase in social interactions between employers and FDWs had enhanced the boundaries that divide them (Ozyegin, 2001) in particular the racial differences as demonstrated in the remark made by the employer of F5 suggesting her to follow the Chinese ways of work.

In addition, the requirement of F5 to move out of her room to make way for her employer’s son symbolises the status distinction among household members, demonstrating the unequal rights to the use of space (Constable, 2009; Rollins, 1985). During the Covid-19 pandemic, F5 became excluded from being sheltered in a private environment from the chaotic public world (Cheal, 1991; Lasch, 1977). In order to keep her privacy, F5 ended up not calling her family and friends, and was forced to become a “socially dead” (Anderson, 2000: 121) and was “socially inaccessible” (Zerubavel, 1981:138). This FDWs’ response had caused a high toll on their emotional health.

Another impact of Covid-19 on the FDWs was the increase of workload. According to a March survey, more than half of surveyed FDWs reported increased workload after the outbreak (Wong, 2020). The story of I1 revealed that the increased workload was related to the Covid-19–induced practices such as WFH and Zoom teaching:

Prior to the virus outbreak, I used to cook only two meals: breakfast and dinner. Now, everyone is staying home, I have to cook three meals and snacks. After midnight, I have to serve my employer’s two daughters who attend evening/mid-night Zoom classes in the US. I can’t go to sleep earlier.

Furthermore, the story of I3 illustrates the higher hygiene expectations from many Hong Kong employers during Covid-19:

My employer sets up cleaning procedures that every time I come back home, I must have a shower and wash all my clothes immediately, but she doesn’t allow me to use washing machine for my clothes. I also need to regularly clean surface tops, door knobs, washing basins, etc. However, my employer refuses to buy me any gloves. I’m totally exhausted by the extra cleaning work and my hands have itchy rashes after frequent use of detergents.

Additional chores were created as a result of Covid-19, and the FDWs were expected to take on additional duties with unquestioning compliance. The employer asserted her ownership of the FDWs’ body (Lyon, 2004). To the employer, hygiene was not only related to the fear of the virus but also to their regard of the FDWs as impurity and pollution and their clothes should not be washed in the family’s washing machine (Barbosa, 2007). They also had dismissed the FDWs’ bodies as tireless and invincible (Pinho, 2015) and did little consideration about the toxic effects of the detergents causing I3’s allergic reactions. By requiring additional hygienic work from the FDWs, the employer put the FDW’s body and personality into the continuum of cleanliness and dirt which resonated with the idea that FDWs equated with dirt and pollution, reinforcing the FDWs’ inferiority in terms of class, gender, and migration embedded in inequality. The fact that the employer did not assume the responsibility to protect the FDWs from the damages caused by the overuse of toxic cleaning products also reflected the disposable position of FDWs (Anderson, 2000).

Prior literature informed that FDWs had a certain agency to resist the unreasonable demands by resigning from the job or looking for a better employer (Tam, 2019). However, during the Covid-19 pandemic, many of them had lost their agency as the story of F4 illustrates such powerlessness:

I don’t dear to say no to her (employer) command. My friend answered back her employer and got fired last month. She can’t find a new job after two weeks and has to go home. But after Manila lockdown, there are not many flights and the price of a one-way ticket to Manila costs more than HK$4,000 which is triple of the normal fare. When she arrives at Manila, she was stuck there because all the transportations have been cancelled and she doesn’t know when she can go back home. I don’t want to end up like her.

The 2-week rule remained a determining factor for decreasing the bargaining power of FDWs. It was detrimental to the FWDs’ wellbeing and welfare during the Covid-19 pandemic since they could not negotiate with their employer’s increasing work demand for fear that they would be terminated. In addition, immobility in the home country had also played a role diminishing the FDWs’ bargaining power.

Worsening employment rights and entitlements

Another impact of the pandemic was that they had to work during their rest days (Chan, 2020). The employment contract of FDWs had given them the right to take one day-off per week. During their day-off, FDWs could build up their social capital by enhancing social contacts and networks so as to get information on their rights (Kang, 2016). However, they were advised not to go out on their rest days (Hong Kong Government, 2020). At the same time, the social media had criticised FDWs’ social gatherings violating social distancing measures which had been under the spotlights of surveillance by the public (RTHK, 2000; Zhang, 2020). The employers also put pressure on the FDWs from leaving home during their days off. However, when FDWs stayed at home, they “lived at work” (Chan, 2020) since some employers requested them to perform more work which had deprived them from resting.

F1 recounted her experience of going out during Covid-19 s wave:

I stay at home because my employer told me to. However, I told her that I like to rest in the small corner behind the kitchen. However, they keep on coming around my rest place to ask me to do things. I asked my employer if she can pay me instead, but she doesn’t respond to my request. Then, I tell her I need to go to church on my off-days, she argues it isn’t safe and he doesn’t want me to bring back any virus. I find her argument doesn’t make sense because I have to go to the wet market more often when everyone eats at home.

FDWs were not protected from illegal dismissal when they refused to work on their rest days. Some FDWs reported that they had not gone out on their off-days for more than nine consecutive weeks (Wong, 2020), and were forced to play “socially dead” (Anderson, 2000: 121) to minimise any risk of unemployment. The FDWs had neither any formal routes to pressure the employers to abide the employment contract nor any negotiation power to voice out their rights openly which had allowed some employers to become “wage thefts” (Segarra & Prasad, 2019: 180). The live-in requirement had turned “home” into workplace which had no boundary between them, and when the FDWs could not go out to their self-created “private zones” in the public areas (Yeoh & Huang, 1998) during off-days, their physical and mental health was harmed (Negi, 2011).

The employers restricted the FDWs’ mobility in their off-days arguing that could protect the FDWs from catching the virus in public. However, the employers contradicted themselves by forcing another form of mobility on the FDWs to run an increasing number of errands in the public due to the fact that the employers wanted to stay safe at home. Thereby, it reveals a categorisation into those whose lives are highly valued and preserved and those whose lives are less valued and potentially disposable (Bejan, 2020). Therefore, a link can be seen between immobility governance and pre-existing inequality regimes by the case of Covid-19. In other words, this denied mobility is an exploitative means by which the employers could conveniently asked the FDWs to do more work while they stayed at home. The double standards imply the conflicting objectives when FDWs were obliged to be exposed to Covid-19 while they physically went out to keep the employer’s household running but without taking into consideration of their health risk (Levitas, 1996).

Discussion

The experience of FDWs in Covid-19 shows that their rights were denied which was connected to their social positioning, both shaping and being shaped by social relations and power asymmetries (Cook & Butz, 2018; Cresswell, 2010). This contrasting capacity of FDWs’ socio-spatial mobility indicated that they were socially excluded as they could not choose to move and do things at their own will during the Covid-19 epidemic. The immobility, visibility, and blurred work boundary had created a combination of effects on the worsening working conditions experienced by the FDWs.

Covid-19 had resulted in an intensified form of precariousness (Butler, 2012) experienced by the FDWs. Their existence in Hong Kong depended on those who navigate the hegemonic institutions that structure the Hong Kong society (Butler, 2012: 148) in which race, gender, class, and migration status inform the substance and degree of precariousness (Fotaki & Prasad, 2015). In some of its most extreme forms, the precariousness experienced by the FDWs can be analytically understood by accounting for its underlying enabling mechanism of dehumanisation such as the employer’s conflicting demands on the FDWs.

Prior to the Covid-19, FDWs had already been working in an invisible form of employment as their work takes place at home, without any co-workers, and in isolation behind closed doors (Andall, 2000). During the Covid-19 epidemic, their work had experienced dramatic changes — on one hand, being more visible and exposed to the employers’ scrutiny when their employers WFH, and on the other hand, being more invisible outside employer’s home since they were advised not to go out on their off-days. Their capacity to demonstrate agency (Näre, 2007) had been diminished by Covid-19. Their amplified visibilities/invisibilities and mobility/immobility were the major causes contributing to the decrease of their agency. Their work had become more undervalued with diminished agency.

Through the lens of Covid-19 pandemic, two major types of paradoxes — visibility/invisibility and mobility/immobility — were discovered in relation to recent developments in FDWs’ employment relations in Hong Kong. These two paradoxical forces had moved simultaneously and increasingly subject the FDWs to worsening conditions in both home and host countries. It can be argued that the simultaneous paradoxes are in fact an instrumentalisation of FDWs in current FDWs’ work discourses and practices in Hong Kong (Dobrowolsky, 2007). The FDWs, who used to be considered an anomaly, had their basic labour rights of FDWs further denied under the Covid-19 pandemic.

Their harsher working conditions constitute one of the examples for how gender and race inequalities were constructed, condoned, and/or reproduced by the government which disregarded the FDWs’ rights and protections in the neoliberal labour market (Lee & Wong, 2004). The highly restrictive, exploitative, and abusive relationships enabled by the government impacted negatively on the wellbeing and welfare of the FDWs.

Covid-19 had prolonged FDWs’ experience of being unseen by others when they worked in a private place inside employer’s home without any co-workers but at the same time, experiencing the increased supervision from WFH employers. This contributes to their invisibility/visibility paradox. Their sense of connectedness to the surrounding world (Scotland-Stewart, 2007) could only be re-established when they go out attending social gatherings on their rest days. However, their only rights of the days off was deprived by social distancing measures which could create within individual FDW a feeling of not being a person of worth (Franklin & Boyd-Franklin, 2000).

The employers sustained a hierarchical distance from their FDWs transforming them into an embodied class “habitus” (Bourdieu, 1977). With the economic downturn brought by Covid-19 pandemic, the FDWs had to display more subservience to safeguard their employment. The Covid-19 pandemic had highlighted the hierarchical difference between the employer and FDWs, and FDWs were downgraded to a mere marginal existence during Covid-19.

Conclusion

Covid-19 had caused the FDWs to face constellations of inequalities in multiple ways.

In summary, the FDWs were exposed to mobility/immobility measures imposed both at the national, familial, and individual levels, subject to the paradoxes of visibility/invisibility, pressured to intensified labour, deprived of legal labour entitlement subject to more employment insecurity, subject to more exploitation from various stakeholders: employment agencies, governments, employers, etc., subject to less agency and less power to resist and bargaining power, and exposed to more physical and mental health risks.

The ambivalences involved in the work was that their labour was intensified as Covid-19 had also exposed them to various mobility/immobility measures imposed both at the national, familial, and individual levels which in turn made the FDWs more subject to the paradoxes of visible/invisible and mobility/immobility. It has negatively impacted on the FDWs’ attempts to resist during Covid-19, and they had to turn to a more passive mode of resistance as “socially dead” when their privacy was intruded rather than a more active resistance approach of resignation which they could use before Covid-19.

Limitations and strengths

This paper examines female FDHs only, and might not be applicable to male FDHs who make up 2% of FDHs in Hong Kong. Furthermore, the paper complements existing studies which viewed the phenomenon of FDHs from a sociological or feminist perspective, focusing on the rights of FDHs working in a constrained environment (Hochschild, 2000; Yeoh & Huang, 1998) as it took a phenomenological research design to providing a voice to FDHs.

Implications

This study reveals the necessity for the government to review the situations of FDHs as the demand of FDWs is projected to increase in double from 380,000 to 600,000 in 10 years due to the ageing population in Hong Kong. Furthermore, the Chinese government has indicated to open up its labour market and would pay up to three times the salary than those of Hong Kong (Siu, 2018). It may cause a drain of the supply of FDWs from Hong Kong. If the negative impacts of Covid-19 experienced by the FDWs were not improved, the FDWs might choose to work somewhere else which would be detrimental to Hong Kong’s economy.

References

Amnesty International (2020). Refugees and migrants forgotten in COVID-19 crisis response, 14 May https://reliefweb.int/report/world/refugees-and-migrants-forgotten-covid-19-crisis-response

Andall, J. (2000). Gender, migration and domestic service. Ashgate.

Anderson, B. (2000). Doing the dirty work” the global politics of domestic labour. University of Chicago Press.

Arat-koç, S. (2012). Paradoxical invisibility and hyper-visibility of gender in policy making and policy discourse in neoliberal Canada. Canadian Woman Studies, 29(3), 6–18.

Barbosa, S. (2007). Domestic workers and pollution in Brazil’. In B. Campkin & R. Cox (Eds.), Dirt: New Geographies of Cleanliness and Contamination (pp. 25–33). I.B. Tauris.

Bejan, R. (2020). COVID-19 and disposable migrant workers, Verfassungsblog, 16 April, https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/78985/COVID-19%20and%20Disposable%20Migrant%20Workers%20_%20Verfassungsblog.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

Bern, P.L. (2004). Domestic service and the formation of European identity: Understanding the globalization of domestic work, 16th–21st centuries.

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994). Critical service encounters: The employee’s viewpoint. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 95–106.

Boje, D. M. (2001). Narrative methods for organization research and communication research. Sage.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

Brisola, E. B. V., & Cury, V. E. (2016). Researcher experience as an instrument of investigation of a phenomenon: An example of heuristic research. Estudos De Pasiigo, 33(1), 95–105.

Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Brush, B., & Vasupuram, R. (2006). Nurses, nannies and caring work: Importation, visibility and marketability. Nursing Inquiry, 13(3), 181–185.

Butler, J. (2012). Precarious life, vulnerability, and the ethics of cohabitation. Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 26(2), 134–151.

Carvalho, R. (2020). Limited food, no wages’: Domestic workers struggle amid quarantine in Hong Kong, 21 June, South China Morning Post.

Carvalho, R., Cheung, E. & Siu, P. (2020). Coronavirus: Hong Kong families await return of thousands of stranded domestic helpers as the Philippines lifts travel ban, 18 February, South China Morning Post.

Chan, A. (2020). Hong Kong’s domestic workers: When ‘Stay at Home’ means ‘Live at Work’, 14 April, The Diplomat.

Cheung, C. K., Chung, S. F., Ho, W. C., & Fung, E. (2017). Employers’ concern does not help foreign domestic workers sustain quality of life in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 27(3–4), 174–186.

Cheal, D. J. (1991). Family and the state of theory. University of Virginia.

Conklin, T. A. (2007). Method or madness: Phenomenology as knowledge creator. Journal of Management Inquiry, 16(3), 275–287.

Cook, N., & Butz, D. (2016). Mobility justice in the context of disaster. Mobilities, 11(3), 400–419.

Cook, N., & Butz, D. (2018). Gendered mobilities in the making: Moving from a pedestrian to vehicular mobility landscape in Shimshal. Pakistan. Social & Cultural Geography, 19(5), 606–625.

Constable, N. (2009). Migrant workers and the many states of protest in Hong Kong. Critical Asian Studies, 41(1), 143–164.

Cresswell, T. (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. In T. Cresswell & P. Merriman (Eds.), Geographies of mobility: Practices, spaces, subjects. Ashgate.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

De Janvry, A., & Garramon, C. (1977). The dynamics of rural poverty in Latin America. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 4(3), 206–216.

Dobusch, L., & Kreissl, K. (2020). Privilege and burden of im-/mobility governance: On the reinforcement of inequalities during a pandemic lockdown. Gender, Work and Organization. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12462

Dobrowolsky, A. (2007). (In)Security of citizenship: Security, im/migration and shrinking citizenship regimes. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 8(2), 629–661.

Elliot, A. & Urry, J. (2010). Mobile Lives: Self, Excess and Nature. Routledge, U.K.

Enrich (2019). The challenges for Hong Kong’s domestic workers, https://helpfordomesticworkers.org/en/key-issues/

Fotaki, M., & Prasad, A. (2015). Neoliberal capitalism and economic inequality in business schools. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 14(4), 556–575.

Franklin, A. J., & Boyd- Franklin, N. (2000). Invisibility syndrome: A clinical model of the effects of racism on African-American males. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 33–41.

Gabriel, Y. (1995). The unmanaged organization: Stories, fantasies, subjectivity. Organization Studies, 16(3), 477–501.

Gabriel, Y. (2000). Storytelling in organizations: Facts, factions, and fantasies. Oxford University Press.

Goodman, L. A. (1961). Snowball sampling. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32(1), 148–170.

Groves, J. M., & Lui, L. (2012). The ‘Gift’ of help: Domestic helpers and the maintenance of hierarchy in the household division of labour. Sociology, 46(1), 57–73.

Hochschild, A.R. (2000). Global care chains and emotional surplus value. In W. Hutton, & A. Giddens, (Eds.), On the edge: Living with global capitalism. London: Jonathan Cape.

Hong Kong Census & Statistics Department (2019). Domestic helpers, https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/sp430.jsp

Hong Kong Government (2020). Frequently asked questions on new requirements to reduce gatherings, https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/social_distancing-faq.html

Huang, F. & Yeung, H. (2018). Institutions and economic growth in Asia: The case of Mainland China, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia. Routledge, New York.

Huang, S., Teoh, B. S., & Toyota, M. (2015). Caring for the elderly: The embodied labour of migrant care workers in Singapore. Global Networks, 12(2), 195–215.

ILO (2010). Decent work for domestic workers, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_104700.pdf

In, N.H. (2016) .Helper abuse still widespread in Hong Kong, says 'Erwiana: Justice for all filmmaker, 25 June, Forbes.

Kang, J. (2016). Study reveals 95% of Filipino, Indonesian helpers in Hong Kong exploited or forced labor, 18 March, Forbes.

Lamont, M. (1992). Money, morals and manners: The culture and the French and the American Upper Middle Class. University of Chicago Press.

Lan, P. C. (2003a). Maid Or madam? Filipina Migrant Workers and the Continuity of Domestic Labor, Gender & Society, 17(2), 187–208.

Lan, P. C. (2003b). Negotiating social boundaries and private zones: The micropolitics of employing migrant domestic workers. Social Problems, 50(4), 525–549.

Lan, P. C. (2006). Global Cinderellas: Migrant domestics and newly rich employers in Taiwan. Duke University Press.

Lasch, C. (1977). Haven in a heartless world. Basic Books.

Lee, K. M., & Wong, H. (2004). Marginalized workers in postindustrial Hong Kong. The Journal of Comparative Asian Development, 3(2), 249–280.

Levitas, R. (1996). The concept of social exclusion and the new Durkheimian hegemony. Critical Social Policy, 16, 5–20.

Listiyorini, E. (2020). Jakarta orders offices to close, bans gatherings to combat virus. 7 April, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-07/jakarta-orders-offices-to-close-bans-gatherings-to-combat-virus

Lyon, S. (2004). An anthropological analysis of local politics and patronage in a Pakistani Village. Edwin Mellen Press.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). Sage.

Näre, L. M. (2007). A remarkable study on transnational caregiving. Finnish Journal of Ethnicity and Migration, 2(2), 44–46.

Negi, N. J. (2011). Identifying psychosocial stressors of well-being and factors related to substance use among Latino Day laborers’. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(4), 748–755.

Nippert-Eng, C. (1995). Home and Work: Negotiating Boundaries through Everyday Life. University of Chicago Press.

Ozyegin, G. (2001). Untidy gender: Domestic work in Turkey. Temple University Press.

Pinho, P. S. (2015). The dirty body that cleans: Reproductions of domestic workers in Brazilian common sense. Meridian, 13(1), 103–28.

Progressive labour union of domestic workers in Hong Kong (2020). https://www.facebook.com/pludwhkunite/

Ranada, P. (2020). Explainer: What’s modified ECQ and modified GCQ?, 12 May Rappler, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/260650-explainer-what-is-modified-ecq-gcq

Rollins, J. (1985). Between women: Domestics and their employers. Temple University Press.

RTHK (2000). Close pedestrian areas to stop helpers gathering, 30 March, https://news.rthk.hk/rthk/en/component/k2/1517693-20200330.htm

Scotland-Stewart, L. (2007). Social invisibility as social breakdown: Insights from a phenomenology of self, world, and other. Stanford University Press.

Segarra, P., & Prasad, A. (2019). Colonization, migration, and right-wing extremism: The constitution of embodied life of a dispossessed undocumented immigrant woman. Organization, 27(1), 174–187.

Siu, J. (2018). Why foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong must live in their employers’ home, 14 Feb, South China Morning Post, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/community/article/2133377/why-hong-kong-wants-foreign-domestic-helpers-live-their

Spiegelberg, H. (1978). The essentials of the phenomenological method. In H. Spiegelberg (Ed.), The phenomenological movement: A historical introduction (pp. 653–701). Vol. 2, 2nd edition.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Sage.

Sutrisno, B. (2020). 50 days of Indonesia’s partial lockdown. Is it enough for the ‘new normal’? 29 May, Jakarta Post, https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/05/28/50-days-of-indonesias-partial-lockdown-is-it-enough-for-the-new-normal.html.

Tam, D. (2019). Bordering are: The care of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong. Cultural Studies, 33(6), 989–1007.

Wong, R. (2020). Coronavirus: Hong Kong migrant domestic workers ‘vulnerable’ during outbreak – NGO, 17 March, Hong Kong Free Press, https://hongkongfp.com/2020/03/17/coronavirus-hong-kong-migrant-domestic-workers-vulnerable-outbreak-ngo/

Yeoh, B., & Huang, S. (1998). Negotiating public space: Strategies and styles of migrant female domestic workers in Singapore. Urban Studies, 35, 583–602.

Yu, T.W. (2016). Foreign domestic workers’ living conditions survey, Transient Workers Count Too, June https://idwfed.org/en/resources/foreign-domestic-workers-living-conditions-survey/@@display-file/attachment_1

Zerubavel, E. (1981). Hidden rhythms: Schedules and calendars in social life. University of Chicago Press.

Zhang, K. (2020). Coronavirus: Hong Kong’s domestic helpers getting used to new normal as social distancing keeps them apart on only day off, 29 March, South China Morning, Post https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/3077463/coronavirus-hong-kongs-domestic-helpers-getting-used-new-normal

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

May, W.M.L. The impacts of Covid-19 on foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong. Asian J Bus Ethics 10, 357–370 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-021-00135-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-021-00135-w