Abstract

We report the general public’s perceptions and those of 15-year-old school students, about aspects of mathematics learning. For the adult sample, survey data were gathered from pedestrians and Facebook users in Australia, Canada and the UK—countries in which English is the dominant language spoken. Participants responded to items about the teaching and learning of mathematics, the gender stereotyping of mathematics and the perceived importance of studying mathematics for future careers. Collection of the data from the pedestrian samples partially overlapped with the period of data gathering via Facebook and coincided loosely with the administration of the Programme for International Student Assessment [PISA] 2012 in the three countries of interest. We examined participants’ views/beliefs by country and by respondent age. We also compared the results of the adult samples with student responses to four PISA 2012 attitudinal items for which the foci were comparable to items administered to the general public. Thus, we were able to compare the responses of three different age groups. While participants considered mathematics to be important for everyone to study, and important for employment, vestiges of traditional gender stereotyped beliefs and expectations were evident, more so among the younger than older respondents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Information retrieved (September 2014) from: http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/action/showMostAccessedArticles?journalCode=jresematheduc

In this article, we use gender to describe differences between males and females that are not attributable to biology; sex is used to denote biologically based differences. Gender, as a term, evolved following debates on whether all differences can be attributed to biology alone. Researchers in earlier times often used sex when today gender would be used; as appropriate, we have respected earlier authors’ terminology use.

Facebook’s advertising system is competitive, that is, the amount paid influences the frequency that an advertisement might appear on the Facebook pages of random users. Clicking on the advertisement was necessarily voluntary, as was completion of the survey. A detailed description of the procedure used to invite participants via Facebook is provided in Forgasz, Leder and Tan (2014).

The ABS data for 2012 guided the original selection of 40 years as the cut-off point. The ABS (2016) data confirmed thestability of the median age of the Australian population.

References

Archer, L., Dewitt, J., Osborne, J., Dillon, J., Willis, B., & Wong, B. (2012). Balancing acts: elementary school girls’ negotiations of femininity, achievement, and science. Science Education, 96(6), 967–989.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2007). Life matters. Gender equity in Australia: All for nothing? Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/lifematters/gender-equity-in-australiaall-for-nothing/3395734.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012). 3235.0—Population by age and sex, regions of Australia, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/3235.0∼2012∼Main+Features

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016). 3101.0 - Australian Demographic Statistics, Jun 2016 Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/1CD2B1952AFC5E7ACA257298000F2E76?OpenDocum

Australian Human Rights Commission (2014). Face the facts. Retrieved from http://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications

Bank, B. J. (2007). Gender and education: an encyclopedia. Westport, CN: Praeger.

Buschor, C. B., Kappler, C., Frei, A. K., & Berweger, S. (2014). I want to be a scientist/a teacher: students’ perceptions of career decision-making in gender-typed, non-traditional areas of work. Gender and Education, 26(7), 743–758.

Gómez-Chacón, I., Leder, G., & Forgasz, H. (2014). Personal beliefs and gender gaps in mathematics. In P. Liljedahl, C. Nicol, S. Oesterle, & D. Allan (Eds.), Proceedings of the Joint Meeting of PME 38 and PME-NA 36 (Vol. 3, pp. 193–200). Vancouver, Canada: The International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education.

Connell, R. W. (2002). Gender. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Corder, G. W., & Foreman, D. I. (2009). Nonparametric statistics for non-statisticians: a step-by-step approach. New Jersey: Wiley & Sons.

Cotter, D. A., Hermsen J. M., & Vanneman, R. (2012). CCF gender revolution symposium: is the gender revolution over? Retrieved from https://contemporaryfamilies.org/is-the-gender-revolution-over/

Damarin, S. K. (2000). The mathematically able as a marked category. Gender and Education, 12(1), 69–85.

Department of Labour and Mattingly Advertising. (1989). Summary of two stage campaign evaluation study. Girls’ career and subject choice. Melbourne: Author.

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2013). The nature-nurture debates: 25 years of challenges in understanding the psychology of gender. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(3), 340–357. doi:10.1177/1745691613484767.

Eccles, J. S. (1994). Understanding women’s educational and occupational choices: applying the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18, 585–609.

Eccles, J. S. (1986). Gender-roles and women’s achievement. Educational Researcher, 15(6), 15–19.

Eccles (Parsons) J., Adler T. F., Futterman R., Goff S. B., Kaczala C. M., Meece J. L., & Midgley C. (1983). Expectations, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

EFA global monitoring report team. (2015). Gender and the EFA 2000–2015: achievements and challenges. Paris, France: UNESCO Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/2015-efa-gender-report.

Else-Quest, N. M., Hyde, J. S., & Linn, M. C. (2010). Cross-national patterns of gender differences in mathematics: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 103–127.

Farley, R., & Haaga, J. (2005). The American people: census 2000. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Fennema, E., & Sherman, J. (1977). Sex-related differences in mathematics achievement, spatial visualization and affective factors. American Educational Research Journal, 14, 51–71.

Fennema, E., & Sherman, J. A. (1976). Fennema-Sherman mathematics attitude scales: instruments designed to measure attitudes toward the learning of mathematics by females and males. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 7, 324–326.

Forgasz, H. J., Leder, G. C., & Tan, H. (2014). Public views on the gendering of mathematics and related careers: international comparisons. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 87, 369–388.

Francis, B. (2010). Girls’ achievement: contesting the positioning of girls as the relational ‘achievers’ to ‘boys’ underachievement’. In C. Jackson, C. F. Paechter, & E. Renold (Eds.), Girls and education 3–16: continuing concerns, new agendas (pp. 21–37). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Francis, B., & Skelton, C. (2005). Reassessing gender and achievement. Questioning contemporary key debates. New York: Routledge.

Hall, J. (2014). Gender-neutral, yet gendered: exploring the Canadian general public’s views of mathematics. In P. Liljedahl, C. Nicol, S. Oesterle, & D. Allan (Eds.), Proceedings of the Joint Meeting of PME 38 and PME-NA 36 (Vol. 3, pp. 225–232). Vancouver, Canada: The International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education.

Halpern, D. F., Benbow, C. P., Geary, D. C., Gur, R. C., Hyde, S. H., & Gernsbacher, M. A. (2007). The science of sex differences in science and mathematics. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 8, 1–51.

Henrion, C. (1997). Women in mathematics. The addition of difference. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Hyde, J. S., & Meertz, J. E. (2009). Gender, culture, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, 106, 8801–8807.

Leder, G. C. (1992). Mathematics and gender: changing perspectives. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 597–622). New York: Macmillan.

Leder, G. C., & Forgasz, H. J. (2010). I liked it till Pythagoras: the public’s views of mathematics. In L. Sparrow, B. Kissane, & C. Hurst (Eds.), Shaping the future of mathematics education: Proceedings of the 33rd annual conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia (pp. 328–335). Fremantle, Australia: MERGA.

Leder, G. C., & Forgasz, H. J. (2011). The public’s views on gender and the learning of mathematics: does age matter? In J. Clark, B. Kissane, J. Mousley, T. Spencer, & S. Thornton (Eds.), Mathematics: traditions and [new] practices (pp. 446–454). Adelaide: AAMT and MERGA.

Leder, G. C., Forgasz, H. J., & Jackson, G. (2014). Mathematics, English and gender issues: do teachers count? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(9).

Leder, G. C., Forgasz, H. J., & Solar, C. (1996). Research and intervention programs in mathematics education: a gendered issue. In A. Bishop, K. Clements, C. Keitel, J. Kilpatrick, & C. Laborde (Eds.), International handbook of mathematics education, part 2 (pp. 945–985). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Marginson, S, Tytler, R, Freeman, B and Roberts, K (2013). STEM: country comparisons. Report for the Australian Council of Learned Academies. Retrieved from www.acola.org.au

McAnalley, K. (1991). Encouraging parents to stop pigeon-holing their daughters: the “Maths Multiplies Your Choices” campaign. Victorian Institute of Educational Research Bulletin, 66, 29–38.

McHugh, M. L. (2013). The chi-square test of independence. Biochemia Medica, 23(2), 143–149 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900058/.

OECD. (2003). Literacy skills for the world of tomorrow. Further results from PISA 2000. OECD/UNESCO-UIS 2003. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/2960581.pdf

OECD. (2013a). OECD skills outlook 2013: first results from the Survey of Adult Skills. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204256-en

OECD. (2013b). PISA 2012 results in focus. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results.htm

OECD. (2013c). PISA 2012 results: ready to learn. Volume III. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results.htm

OECD. (2014). PISA. Are boys and girls equally prepared for life? Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/PIF-2014-gender-international-version.pdf

OECD. (2015). The ABC of gender equality in education: aptitude, behaviour, confidence. PISA: OECD Publishing Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264229945-en.

OECD. (n.d.) About PISA. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/aboutpisa

Powlishta, K. K. (2002). Measures and models of gender differentiation. The developmental course of gender differentiation: conceptuality, measuring and evaluating constructs and pathways. In L. S. Liben & R. Bigler (Eds.), Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 67(2), 167–178.

Survation charities & campaign groups (2016). Attitudes to gender in 2016 Britain—8,000 sample study for Fawcett Society. Retrieved from survation.com/uk-attitudes-to-gender-in-2016-survation-for-fawcett-society/

Thomson, S., De Bortoli, L., & Buckley, S. (2013). PISA 2012: how Australia measures up. Camberwell, Vic: Australian Council for Educational Research [ACER].

van Egmond, M., Baxter, J., Buchler, S., & Western, M. (2010). A stalled revolution. Gender role attitudes in Australia, 1986-2005. Journal of Population Research. Retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com/content/83t4k56g58866h43/fulltext.pdf

Wiersma, W. (1995). Research methods in education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Karen Skilling (UK) and Jennifer Hall (Canada) for gathering the pedestrian survey data in the UK and Canada, and Natalie Kalkhoven for assisting with the production of the graphs and data analyses. Funding to support the conduct of this study was received from the Faculty of Education, Monash University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The full set of survey items, with closed response options and supplementary prompts shown in parentheses:

-

When you were at school, did you like learning Mathematics? [Yes/No/Unsure. Why do you say that?]

-

Were you good at Mathematics? [Yes/No/Average. Why do you say that?]

-

Has the teaching of Mathematics changed since you were at school? [Yes/No/Don’t know. If “yes”, how?]

-

Should students study Mathematics when it is no longer compulsory? [Yes/No/Don’t know. Why do you say that?]

-

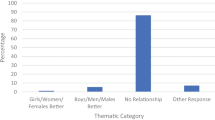

Who are better at Mathematics, girls or boys? [Girls/Boys/Same/Don’t know. Why do you say that]

-

Do you think this has changed over time? [Yes/No/Don’t know. If “Yes”, how have things changed?]

-

Who do parents think are better at Mathematics, girls or boys? [Girls/Boys/Same/Don’t know. Why do you say that?]

-

Who do teachers think are better at Mathematics, girls or boys? [Girls/Boys/Same/Don’t know. Why do you say that?]

-

Do you think that studying Mathematics is important for getting a job? [Yes/No/Don’t know. If “Yes”, why do you say that?]

-

Is it more important for girls or boys to study Mathematics? [Girls/Boys/Same/Don’t know. Why do you say that?]

-

Who are better at using calculators, girls or boys? [Girls/Boys/Same/Don’t know. Why do you think that?]

-

Who are better at using computers, girls or boys? [Girls/Boys/Same/Don’t know. Why do you think that?]

-

Who are more suited to being scientists, girls or boys? [Girls/Boys/Same/Don’t know. Why do you think that?]

-

Who are more suited to working in the computer industry, girls or boys? [Girls/Boys/Same/Don’t know. Why do you think that?]

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forgasz, H.J., Leder, G.C. Persistent gender inequities in mathematics achievement and expectations in Australia, Canada and the UK. Math Ed Res J 29, 261–282 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-017-0190-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-017-0190-x