Abstract

Studies of depression and its outcomes in older people living with HIV (PLWH) are currently lacking in sub-Saharan Africa. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in PLWH aged ≥ 50 years in Tanzania focussing on prevalence and 2-year outcomes of depression. PLWH aged ≥ 50 were systematically recruited from an outpatient clinic and assessed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Neurological and functional impairment was assessed at year 2 follow-up. At baseline, 253 PLWH were recruited (72.3% female, median age 57, 95.5% on cART). DSM-IV depression was highly prevalent (20.9%), whereas other DSM-IV psychiatric disorders were uncommon. At follow-up (n = 162), incident cases of DSM-IV depression decreased from14.2 to 11.1% (χ2: 2.48, p = 0.29); this decline was not significant. Baseline depression was associated with increased functional and neurological impairment. At follow-up, depression was associated with negative life events (p = 0.001), neurological impairment (p < 0.001), and increased functional impairment (p = 0.018), but not with HIV and sociodemographic factors. In this setting, depression appears highly prevalent and associated with poorer neurological and functional outcomes and negative life events. Depression may be a future intervention target.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There are over 38 million people living with HIV (PLWH) worldwide (UNAIDS 2019). New infections total 1.7 million annually, two thirds of which occur in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (UNAIDS 2019). Rapidly expanding access to combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) has markedly increased life expectancy of PLWH. In Africa, the population aged ≥ 50 is expected to triple by 2030 from 74.4 to 235.1million (UNAIDS 2014). SSA currently accounts for 60% of all PLWH over the age of 50 (UNAIDS 2014). This newly emergent ageing population brings new challenges in the form of chronic HIV-associated comorbidities.

Mental disorders (primarily depression) are predicted to become the leading cause of disability worldwide by 2030, with over 322 million people currently affected (Bing et al. 2001; Kang et al. 2015). Prevalence data for depression in SSA are currently limited. Based on limited available evidence, an estimated 4% of the adult community population of the WHO Africa region meet criteria for depression, with substantially higher rates in small hospital-based studies (Gbadamosi et al. 2022). Globally, the rates of depression in PLWH appear to be 2–4 times higher than the general population (Bernard et al. 2017) with an estimated pooled prevalence of 9–32% reported in PLWH in SSA. This is important, because depression is well-recognised to negatively impact HIV disease outcomes (in SSA and elsewhere) resulting in treatment failure, higher HIV viral load, and increased mortality.

The pathophysiology of depression in HIV is not well understood. Current hypothesised aetiologies include biological and psychosocial pathways (Nanni et al. 2015). The biological pathway attributes depression to persistent viral presence in the central nervous system (CNS), thus acting as a reservoir (Nanni et al. 2015). This prolongs immunological activation and releases toxic viral proteins and inflammatory cytokines which results in depression as part of a spectrum of neurological impairment due to the resultant neuronal damage (Nanni et al. 2015). This links with the increasingly recognised ‘inflammatory’ hypothesis of depression aetiology in conditions other than HIV, as well as in HIV infection (Mudra Rakshasa-Loots et al. 2022; Osimo et al. 2019; Bell et al. 2017). The psychosocial pathway attributes depression to the psychological burden of living with a chronic, disabling, and stigmatised disease (Nanni et al. 2015), which is particularly pertinent in HIV. Therefore, both biological and psychosocial stressors are likely to be highly relevant in the aetiology of depression in PLWH. Depression and HIV may also have a bidirectional relationship in that depression appears to be both a risk factor for and consequence of HIV infection (Goin et al. 2020). An additional challenge is that depression may be associated with individual cART medications (e.g. efavirenz) and with common comorbidities (particularly tuberculosis (TB)) (Munoz-Moreno et al. 2009; Sweetland et al. 2017).

Despite the newly ageing HIV population on cART, few studies have investigated depression in older PLWH. These studies, appraised in the discussion, mostly use cross-sectional data and longitudinal data are lacking (Rabkin et al. 1997; Johnson et al. 1999; Olley et al. 2006; Rodkjaer et al. 2011; Orlando et al. 2002) (see supplementary Table 4). In addition, existing SSA longitudinal studies of depression in HIV focus almost exclusively on younger populations and/or specific higher risk groups, such as intravenous drug users, marginalised groups, and untreated populations(Antelman et al. 2007; Marwick and Kaaya 2010). Current data, therefore, lack applicability to the cART-treated ageing population rapidly increasing in SSA.

Older PLWH may be at specific increased risk of neurological impairment and disability. For example, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) affect up to 50% of older PLWH worldwide (Heaton et al. 2010). Since depression is a well-recognised risk for and consequence of neurodegenerative dementias (Cipriani et al. 2015), data on neurocognitive outcome of depression in older PLWH is needed and currently lacking.

In summary, depression and HIV are predicted to become the first and second leading causes of disability worldwide by 2030 resulting in huge potential individual and societal consequences for those affected (Bing et al. 2001; World Health Organisation 2020). There is a critical gap in current knowledge regarding depression in older PLWH, potentially modifiable aetiological factors and outcomes. Without assessment of the longer-term effect of depression, progress in low-resource settings may not be prioritised due to lack of evidence to inform policy makers.

We therefore aimed to:

-

1.

Estimate prevalence and risk factors of depression, in the context of other psychiatric disorders, in older PLWH in Tanzania.

-

2.

Estimate longitudinal prevalence of depression and its neurological and functional outcomes in PLWH aged ≥ 50 years receiving standard HIV clinic follow-up.

-

3.

Explore the relationship of depression to the biological and psychological hypothesised aetiological pathways.

Methods

Setting

The study took place at Mawenzi Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) HIV Care and Treatment Centre (CTC) in the Kilimanjaro region of Northern Tanzania. This clinic is a government-run, free-of-charge service. The estimated national prevalence of HIV infection in Tanzania is 4.6% with 71% of those aware of their HIV status receiving treatment (UNAIDS 2018). At baseline (2016), 820 PLWH aged ≥ 50 years were registered with the MRRH clinic. MRRH has a psychiatric clinic, though a trained psychiatrist (responsible for the entire Kilimanjaro region) was recruited only in 2018. Currently, Tanzania has only 0.52 qualified mental health workers per 100,000 population (World Health Organisation 2017).

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research and Kilimanjaro Christian Medical College Research Ethics Committee (No. 896). Verbal and written information was given to each participant before informed consent was obtained. If participants lacked capacity to consent, assent was sought from a close relative. Consent was rechecked at follow-up. The study protocol included locally agreed referral pathways for individuals diagnosed with significant psychiatric disorders.

Recruitment, sampling, and background data

The primary purpose of the baseline study was identification and screening of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) criteria (Antinori et al. 2007). A detailed description of recruitment and baseline assessment has previously been published (Kellett-Wright et al. 2021). In brief, a systematic sample (every third eligible individual) was recruited from March to May 2016. Inclusion criteria were individuals aged ≥ 50 years attending routine follow-up. Those attending emergency appointments too physically unwell to comfortably participate or newly diagnosed were excluded.

Individuals included at baseline were offered annual follow-up to coincide with routine clinic appointments during the annual study follow-up (resource-limited to March to May annually). Longitudinal analysis was limited to individuals completing follow-up evaluation between March and May 2018. Detailed HIV disease severity, e.g. CD4 count or viral load, and comorbidity data were obtained from standardised clinic records as previously reported (Kellett-Wright et al. 2021). Other demographic data were self-reported and corroborated by informants where necessary.

Assessment of psychiatric disorders

Baseline screening and diagnosis of depression and other psychiatric disorders were completed by a doctorate-level specialist nurse and specialist nurse with experience of older person’s mental health research (JR, AK). A local translation of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to screen for depression. The GDS-15 was selected despite cultural limitations as it is widely used in SSA, including in large epidemiological studies (Sarfo et al. 2017; Sokoya and Baiyewu 2003), and no robustly validated alternative currently exists. The GDS translation used had undergone forward and backward translation by local clinicians experienced in mental health care. A cut-off of 5/15 (previously used for ICD-10/DSM-IV depression in SSA) was applied. The GDS was interviewer-administered, an accepted method in low-literacy settings(Almeida and Almeida 1999). Psychiatric disorders were identified using a local translation of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), a widely used structured ‘stem and leaf’ tool which utilises the DSM-IV criteria and is validated for depression screening in PLWH in SSA (Tsai 2014).

Neurological impairment and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder

Neurological symptoms were self-reported by structured questionnaire (supplementary Table 1) and included memory, thinking, balance impairment, subjective slowness, and loss of feeling in the hands/feet.

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) by AAN (2007) criteria were classified by consensus panel (SMP, EML, RA, TL). Full HAND assessment (details previously published (Eaton et al. 2020)) included locally normed low-literacy neuropsychological test battery, structured mental state examination, abbreviated neurological examination, and creation of summary case notes for consensus panel review. As per AAN criteria, HAND were not diagnosed if another more likely neurological or psychiatric cause (including severe depression) was identified.

Functional impairment

Subjective functional impairments (employment/home responsibilities) were self-reported (supplementary Table 1). Informant collateral history to confirm/refute cognitive or functional impairment was obtained, usually from a close relative (by telephone where necessary), with participants’ consent. Informants were told this was a general ageing study and HIV was not mentioned to protect patients’ confidentiality. Overall clinician rating of function was recorded using the Karnofsky performance scale (0–100%) (Peus et al. 2013) widely used in HIV settings. This rating considered self-reported impairment, clinical assessment, and collateral history.

Follow-up assessment

Follow-up assessment (2018) was similar to baseline, with the following changes. (1) All individuals were screened with the GDS-15 and, only if screen positive (≥ 5/15), the DSM-IV depression element of the MINI completed (AK). Other DSM-IV psychiatric disorders were not evaluated due to very low prevalence of disorders other than depression at baseline and to avoid participant fatigue. (2) At follow-up, participants were asked if they had experienced any significant negative life event in the previous 2 years (e.g. bereavement, significant loss, or other negative life event) to ensure these issues were not missed. (3) HIV viral load measurement became locally available in 2017 (following a change in national guidelines) and was included as a HIV disease severity outcome at follow-up. Viral suppression was defined as ≤ 20 copies/ml.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was supported by IBM SPSS (version 26; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Standard descriptive statistics (e.g. mean, median, standard deviation (SD), interquartile range (IQR), and frequency) and inferential tests (e.g. chi-squared, Mann–Whitney U, and t test) were used for group comparisons depending on the level and distribution of the data. All data analyses were two-tailed at a 5% significance level. Only those with full data at both time points were included in longitudinal analysis (253 and 162 participants in 2016 and 2018, respectively).

Results

Of 253 individuals with complete data at baseline 2016, 162 (64.0%) were followed up in 2018 (Table 1). Demographic, HIV disease, and comorbidity characteristics at baseline are summarised in supplementary Table 2 and are also previously published (Kellett-Wright et al. 2021; Eaton et al. 2020). The majority were female (72.3%), educational level was low (64% completed primary education), and current HIV disease control was good (95.5% cART-treated, mean CD4 526.5 mm/l), though most (60%) had advanced disease (WHO stage 3 or 4).

Depression and other psychiatric disorders at baseline (2016)

Affective and non-affective psychiatric disorders by DSM-IV MINI criteria are listed in Table 1. Depression was highly prevalent by both GDS-15 (53, 20.9%) (Table 4) and MINI DSM-IV criteria (42, 16.6%) (Table 1). Few were treated with psychiatric medication (DSM-IV n = 2 (3.8%), GDS-15 n = 3 (7.1%) prescribed low-dose amitriptyline). Other psychiatric disorders (anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders) were uncommon. Alcohol dependence was reported by one participant, and no participants reported other substance misuse.

Neurological and functional impairment at baseline (2016)

Neurological and functional impairments were common (Table 1) particularly neuropathy, headaches, and difficulties with home and work tasks. Almost half (47.0%) met AAN HAND criteria.

Depression at baseline and non-significant outcomes

DSM-IV depression at baseline was not associated with HIV disease severity markers including legacy effect (proxy measure: nadir CD4), current efavirenz prescription or TB treatment, measured sociodemographic factors, or presence of neurocognitive or functional impairments (Table 2).

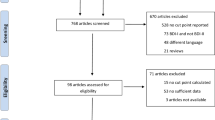

Follow-up cohort 2016–2018

A total of 162 individuals were fully assessed at baseline and follow-up. Those not followed up were not necessarily lost to follow-up by the clinic, but the majority (n = 71) did not attend during the study follow-up window. Those followed up did not significantly differ in demographic (% female, median age, % primary educated) or HIV disease severity factors (mean CD4, WHO stage 1/2 vs 3/4) from those not followed up (supplementary Table 3). Only a small minority (n = 8) had died.

Demographic and HIV disease data at each time point are summarised in supplementary data Table 3. Between baseline and follow-up, GDS-15 depression significantly decreased (20.9% to 13.0% χ2: 4.30, p = 0.038), but there was a non-significant decrease of depression by DSM-IV criteria (16.6% to 11.1%, χ2: 2.41, p = 0.12) (supplementary Table 3, Fig. 1).

Study flowchart. Those followed up in 2018 did not significantly differ in demographic (%female 70.4 95%CI, χ2: 0.87, p = 0.35; median age 59 95%CI, t test: 0.16, p = 0.75; %primary educated 67.9 95%CI, χ2: 6.64, p = 0.25) or HIV disease severity factors (mean CD4 530.2 95%CI, t test: 1.47, p = 0.39, WHO stage 1/2 14.8%, WHO stage 3/4 93.2%) from those not followed up

Two-year outcome of depression at baseline

Outcomes of those with and without DSM-IV and GDS-15 depression at baseline are outlined in Table 3 and supplementary data Table 4, respectively. Most HIV disease outcomes (CD4, viral suppression, WHO stage, medication adherence) were not significantly different in those with and without depression at baseline. There was a trend of higher prevalence of unsuppressed HIV viral load in individuals with both DSM-IV (43.5% n = 10 vs 30.2%, n = 43, p = 0.45) and GDS-15 depression (41.9%, n = 13 vs 29.8%, n = 39, p = 0.83). The use of efavirenz significantly decreased (supplementary Table 3) (53.0% to 31.5% χ2: 91.30, p<0.001), and those on second line cART treatment increased (Tables 3 and 4).

Psychosocial outcomes

Individuals meeting DSM-IV or GDS-15 depression criteria in 2016 were significantly more likely to report negative life events in the previous year at follow-up in 2018 compared to those who did not meet depression criteria at baseline in 2016 (Table 3, supplementary data Table 4). Unemployment at follow-up was associated with baseline depressive symptoms by the GDS-15 (Table 4) but not DSM-IV criteria (Table 3).

Neurological outcomes

Self-reported neurological outcomes are illustrated in Fig. 2. Figure 2 shows those depressed at baseline had poorer neurological outcomes at follow-up compared to those not depressed at baseline. Baseline DSM-IV depression was significantly associated with self-reported neurological impairment (impaired concentration, balance, slow hand movements) at follow-up but not a formal HAND diagnosis (Table 3).

Functional impairment

Figure 3 shows those depressed by both MINI DSM-IV and GDS-15 criteria have poorer functionality by the Karnofsky performance status compared to non-depressed participants. At follow-up, self-reported difficulties with everyday tasks were twice as likely and with home responsibilities three times as likely, in those with depression at baseline (Fig. 2, Table 3). Similarly, over 20% of those with depression at baseline were clinician-rated as substantially functionally impaired (Karnofsky ≤ 70%, indicating need for assistance with daily living activities) compared with ≤ 5% of those without baseline depression (Fig. 3). Prevalence of both HAND and functional impairment increased by 12.3% and 5.1%, respectively, in 2016–2018 though self-reported neurological symptoms decreased by 7.3%.

Discussion

This study is the first to report longitudinal prevalence of depression in older PLWH in SSA alongside biological, psychosocial, and functional outcomes. We report a high depression prevalence (20.9% DSM-IV, 16.6% GDS-15) but were unable to identify other SSA studies using comparable diagnostic criteria.

One South African study (n = 422) reported prevalence of 14.8% by ICD-10 criteria in a demographically similar rural cohort (median age 60 vs 57, % primary educated 52.4 vs 64.0) but with substantially lower cART treatment rates (95.5% vs 49.3%) (Nyirenda et al. 2013). ICD-10 includes more somatic symptoms than DSM-IV, potentially resulting in over-reporting in chronic disease (Almeida and Almeida 1999).

Other high-income (USA) (Balderson et al. 2013; Grov et al. 2010) and middle-income settings (Brazil) (Filho et al. 2012) report prevalence of 39.1% (CES-D), 14.0% (DSM-IV), and 34.6% (GDS), respectively. These are socio-demographically different to this Tanzanian cohort (USA median age 54–55.8, %female 28–28.9, completed high school 78.7–82%) (Balderson et al. 2013; Grov et al. 2010) (Brazil mean age 57.6, %female 44.2, %literate 76.9, cART-treated 94.2%) (Filho et al. 2012).

These studies, like ours, report a high depression prevalence (highest in higher-income settings) despite differing in population demographics and proportion receiving cART. This is surprising as we might expect a higher depression prevalence among cART-untreated individuals given the biological inflammatory pathway hypothesis (Bhatia and Munjal 2014).

Baseline depression did not correlate with the HIV disease severity variables we investigated in contrast to cross-sectional studies which frequently report worse HIV disease outcomes and cART adherence. An East African study (Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda, n = 2307, 58.3%female, median age 34–48) reported that depression was associated with 50% lower cART adherence and increased HIV viral load (Meffert et al. 2019). This older cohort may be unusual given that almost all received cART (vs 68% in the East African study), and self-reported adherence was high (Meffert et al. 2019). We may be observing a ‘healthy survivor’ effect which may be present in other older PLWH cohorts.

Prevalence of other psychiatric disorders

There are few studies reporting prevalence of non-mood psychiatric disorders in HIV, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, and we were unable to identify other studies of psychiatric disorders in older PLWH in SSA. Comparisons with other studies are therefore challenging.

Psychiatric disorders other than depression were low which is consistent with similar findings in the Global Burden of Disease survey (anxiety disorders 3.4% alcohol disorders 1.4% (The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2016)). SSA studies of younger PLWH report higher levels of both anxiety and alcohol disorders. A South African study (n = 65, md age 30) reported a MINI DSM-IV generalised anxiety disorder prevalence of 6.7% and 10.1% alcohol dependence(Olley et al. 2006), whereas 21.7% met anxiety disorder criteria in a larger Nigerian study (n = 300, median age 37) (Olagunju et al. 2012).

Though our cohort included individuals in ‘middle age’, the skew towards older age may be relevant. Anxiety disorders peak in middle age and decrease in older age (Bandelow and Michaelis 2015). Similarly, alcohol misuse peaks at age 25–34 in South African general population data (Trangenstein et al. 2018).

Social circumstances may also be important. Much of our cohort were employed (88.5%) and lived with others (83%) compared to the younger South African cohort where a third lacked family support and unemployment rates were high (24.7%) (Olagunju et al. 2012).

The prevalence of mental disorders tends to be higher in those with chronic disease such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and COPD and increases with the number of chronic diseases (Prince et al. 2007; The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2016). A meta-analysis investigating mental disorders in chronic disease reported a 36.6% prevalence of anxiety and/or depression in chronic disease, compared to 4.4% in the general population, and that chronic disease increased the risk of anxiety and/or depression by 310% using DSM-V and ICD-10 criteria (Dare et al. 2019). The population prevalence of comorbid mental disorders (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia) with chronic diseases is estimated at 45.8% in SSA (Prince et al. 2007; The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2016). It is surprising therefore that this older cohort with a chronic disease burden appears to have lower levels of both depression and other mental disorders (Dare et al. 2019).

Outcomes of depression at baseline

This is the only study we are aware of which investigates longitudinal outcomes of depression in older adults with HIV in SSA. The prevalence of depression appeared to decrease between baseline and follow-up though this was only significant by GDS and not DSM-IV criteria. Longitudinal reductions in depression have been reported in other studies of PLWH (supplementary Table 4), though these are majority male populations in high-income countries and/or intravenous drug user (IVDU) settings. One SSA study reported 8.9% reduction over 6 months, in the context of young PLWH before and after commencing cART (Olley et al. 2006). However, comparing existing data to our majority female cohort of older people stable on cART is challenging.

Persistent depression and chronic inflammation hypothesis

At follow-up, individuals depressed at baseline were more likely to ‘screen-positive’ on the GDS (depressive symptoms) but not to meet case-level DSM-IV. Depression is an episodic disorder and may remit over the 2-year follow-up. However, prior episodes may increase the risk of subsequent ones, in part due to the ‘kindling’ hypothesis where the level of stressor resulting in depression is thought to have less of an effect (Rabkin et al. 1997; Johnson et al. 1999). It is unclear whether these GDS findings represent subthreshold depression.

Chronic ‘subthreshold’ depressive symptoms are common in other chronic inflammatory diseases and also in conditions resulting in damage to frontal pathways (e.g. cerebrovascular disease) commonly reported to occur in chronic HIV infection (Harrison 2017). Increased CNS and peripheral inflammatory biomarkers are reported in depression and may reduce with antidepressant medication (Hegdahl et al. 2016).

HIV disease severity

We hypothesised that depression could be associated with ongoing HIV-related inflammation in this cohort, but baseline depression was not significantly associated with HIV disease severity including viral suppression at follow-up. In contrast, other cross-sectional SSA studies report associations with poor medication adherence, high HIV viral load, and low CD4 count (Ammassari et al. 2004; Olisah et al. 2015). This again may reflect the ‘healthy survivor’ effect and good HIV management seen in this cohort where cART adherence and HIV disease outcomes improved. HIV viral load testing introduction in 2017 may have contributed to this finding, as proportionally, more individuals receiving second-line therapy (indicating treatment failure) increased, and cART adherence also improved, potentially due to improved disease monitoring and clinician feedback.

Lack of association with HIV viral load does not exclude ongoing chronic inflammation as shown by an increased proportion receiving second-line therapy at follow-up. Chronic inflammation resulting from HIV infection may lead to depression (as with other chronic inflammatory conditions) despite a peripherally suppressed HIV viral load, given that the CNS is a ‘reservoir site’ for the HIV virus, due to limited CNS cART penetration (Gray et al. 2014). This potential ongoing CNS inflammation and damage might explain the association of depression with poorer neurological outcomes but not the measured HIV disease outcomes.

There is a high percentage of viraemic individuals at follow-up despite good reported cART adherence, and a larger proportion classified WHO stage 3 or 4 (advanced disease). Several factors may explain this finding. Some evidence suggests older age is hypothesised to increase risk of higher viral load and incomplete immune recovery (Pirrone et al. 2013). Although self-reported medication adherence is high, this may not represent objective adherence. Current guidelines suggest enhanced adherence counselling for low-level viraemia, and since viral load testing became available only a short while before our follow-up phase, many individuals may have undergone counselling prior to a switch to second-line therapy. Additionally, treatment failure may have contributed to this outcome, but we lack data on local resistance patterns.

Neurological impairment

Baseline depression was significantly associated with self- reported neurological and functional impairments at follow-up. It is unclear whether this represents a true increase.

Somatic manifestations of depression are common in older people and in SSA (Grover et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2008). Limited access to mental health services in SSA may result in misdiagnosis of depression as physical illness (Lee et al. 2008). Self-reported ‘slow hand movements’ could represent residual depression symptoms (psychomotor retardation, anergia), somatic representations of distress, or neurological impairment.

Similarly, ‘negative cognitions’ are well-recognised in depression and may persist despite remission, potentially leading depressed individuals to over-report symptoms and impairment.

Self-reported neurological symptoms were associated with depression but the (potentially more objective) clinical diagnosis of HAND. In PLWH, depressive symptoms, but not objective neuropsychological performance, may explain the variance between self-reported and clinical findings (Rourke et al. 1999). Furthermore, self-reported functional impairment may be inaccurate in those with cognitive impairment (Thames et al. 2011). However, over-reporting is unlikely, as baseline neurological and functional impairments were not associated with depression, and other psychiatric diagnoses were uncommon. The significant follow-up associations were self-reported and clinician-rated and included the objective measure of employment. This suggests that negative cognitive biases associated with depression are not the major explanation for our findings.

Psychosocial factors

Given that we found no association between depression and HIV disease factors, psychosocial factors may be relevant. Multiple factors such as isolation, discrimination, stigma, and living with chronic disease have been linked to depression in HIV (Munoz-Moreno et al. 2009). At baseline, we found no association between living alone, unemployment, educational background, and depression, but depression symptoms (GDS-15 ≥ 5) were associated with unemployment at follow-up.

Self-reported significant negative life events at follow-up were more likely in those depressed at baseline though overall depression prevalence reduced. Significant life stress is well-recognised to predict depression (Munoz-Moreno et al. 2009). Our findings suggest a possible bidirectional relationship. As discussed for neurological impairment, events may have been viewed more negatively due to negative cognitive biases (Wenzlaff and Bates 1998).

HIV is well-recognised to negatively impact long-term social and economic outcomes for families (Talman et al. 2013). Kenyan and South African data suggest earnings are lower in PLWH and that reduced earning potential results in sale of valuable assets such as livestock causing ongoing health and economic vulnerability (Talman et al. 2013). PLWH with depression may also be more likely to experience disability and reduced work productivity. In India, depression in HIV was associated with poorer environmental and social quality of life indicators (unemployment, low-income, poor diet, inadequate housing, and lack of life partner) (Charles et al. 2012). Similarly, a Ugandan study reported PLWH with depression (PHQ-9 and MINI) to be more likely to be unemployed and/or have lower weekly income than those without depression (Wenzlaff and Bates 1998). Therefore, depressed PLWH may be at higher risk of negative socioeconomic life events (Deshmukh et al. 2017).

Individuals with depression may be more likely to experience difficult social situations, negative interactions, and selectively focus on negative emotional stimuli (Steger and Kashdan 2009). This may result in fewer intimate relationships, greater negative responses from others, and greater emotional distress in response to social stressors (Steger and Kashdan 2009). Consequently, PLWH with depression may be more likely to experience stressful life events and also respond more negatively to them, creating a double burden of disability, whilst having lower ‘reserve’ due to lower socioeconomic status (Wagner et al. 2012). Conversely other studies report lower subsequent negative life events and stressors at follow-up in those with depression (Olley et al. 2006).

In summary, though comparable longitudinal data are lacking, it seems plausible that both HIV and depression may interact to result in greater self-reported negative life events and worse functional outcomes (‘objective’ and self-reported). Our data indicates that inflammation from HIV onto the CNS and physical stressors work together to manifest depression in PLWH.

Limitations

We selected a local translation of the GDS-15 based on extensive use in SSA but recognise that limitations in transcultural settings are well-recognised (Howorth et al. 2019). Similarly, we used a local translation of the MINI, previously used in the same clinic (Sumari-de Boer et al. 2018), but the low observed prevalence of some psychiatric disorders could be attributable to cultural differences in understanding of the MINI questions. We nevertheless could not identify any robustly validated cultural alternative. Though we report on psychosocial outcomes, we did not obtain information on self-perceived stigma and socioeconomic background, risk, and outcome factors which may have been relevant.

At baseline, psychiatric screening was completed by registered Tanzanian nurses with mental health research experience (one at doctoral level). Despite efforts to develop rapport, sensitivity of the questions and well-recognised stigma associated with mental illness may have led to under-reporting of psychiatric symptoms. Similarly, self-reported negative life events may have been under- or over-reported depending on rapport. Due to scarcity of specialist mental health services in Tanzania, previous psychiatric disorders are likely to be undiagnosed and subsequently under-reported. Similarly, since depression is episodic, depression which was not present during the study period will have been missed.

In 2018, the psychiatric interview was abbreviated to prevent participant fatigue and retain as many participants as possible. Since there were low rates of other psychiatric disorders, we decided to focus on depression. This may have impacted longitudinal findings.

Neurological symptoms were self-reported. A neurological examination was completed at baseline and follow-up but was insufficiently comprehensive to fully corroborate symptoms (e.g. peripheral neuropathy). The lack of HIV viral load testing at baseline limited assessment of HIV disease severity.

We had a relatively high rate of loss to follow-up. However, we were able to verify from clinic records that almost all not evaluated (72/91) remained under active HIV clinic follow-up and only 8/91 were recorded to have died. Though those seen and not seen at follow-up did not differ in recorded sociodemographic factors, it is not clear whether the follow-up cohort was representative in terms of outcome. Individuals with more severe depression may be less likely to engage with medical services, potentially skewing our results (DiMatteo et al. 2000; Dixon et al. 2016).

Study data collection corresponded with the crop-planting (rainy) season. Those failing to attend clinic may have been fitter and prioritising the annual community agricultural activities or, conversely, less able to travel in difficult road conditions.

Conclusion

This is the first longitudinal study of prevalence and outcomes of depression in older PLWH in SSA. Despite well-controlled disease, significant associations were found with neurological and functional impairment and an increased risk of subsequent negative significant life events. This suggests that depression may have long-lasting effects despite remission. This cohort, demographically typical of PLWH in Tanzania, markedly differs from high-income studies of older PLWH. There are likely to be differing aetiologies and risk factors for depression that are not currently understood. Further research should replicate these findings in SSA; identify those at greatest risk; and determine whether interventions can reduce these observed negative outcomes.

Availability of data and material

The authors confirm that deidentified data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, where necessary subject to a data transfer agreement and permission from the Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR).

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Almeida OP, Almeida SA (1999) Short versions of the geriatric depression scale: a study of their validity for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 14:858–865

Ammassari A, Antinori A, Aloisi MS, Trotta MP, Murri R, Bartoli L, Monforte AD, Wu AW, Starace F (2004) Depressive symptoms, neurocognitive impairment, and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. Psychosomatics 45:394–402

Antelman G, Kaaya S, Wei R, Mbwambo J, Msamanga GI, Fawzi WW, Fawzi MC (2007) Depressive symptoms increase risk of HIV disease progression and mortality among women in Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 44:470–477

Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE (2007) Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology 69(18):1789–1799. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b

Balderson BH, Grothaus L, Harrison RG, McCoy K, Mahoney C, Catz S (2013) Chronic illness burden and quality of life in an aging HIV population. AIDS Care 25:451–458

Bandelow B, Michaelis S (2015) Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 17:327–335

Bell JA, Kivimäki M, Bullmore ET, Steptoe A, Carvalho LA (2017) Repeated exposure to systemic inflammation and risk of new depressive symptoms among older adults. Transl Psychiatry 7:e1208

Bernard C, Dabis F, de Rekeneire N (2017) Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12:e0181960

Bhatia MS, Munjal S (2014) Prevalence of depression in people living with HIV/AIDS undergoing ART and factors associated with it. J Clin Diagn Res 8:WC01–4

Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, Turner BJ, Eggan F, Beckman R, Vitiello B, Morton SC, Orlando M, Bozzette SA, Ortiz-Barron L, Shapiro M (2001) Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:721–728

Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Carlesi C, Danti S, Nuti A (2015) Depression and dementia. A Review. Eur Geriatr Med 6:479–486

Charles B, Jeyaseelan L, Pandian AK, Sam AE, Thenmozhi M, Jayaseelan V (2012) Association between stigma, depression and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) in South India - a community based cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 12:463

Dare LO, Bruand PE, Gerard D, Marin B, Lameyre V, Boumediene F, Preux PM (2019) Co-morbidities of mental disorders and chronic physical diseases in developing and emerging countries: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 19:304

Deshmukh NN, Borkar AM, Deshmukh JS (2017) Depression and its associated factors among people living with HIV/AIDS: can it affect their quality of life? J Family Med Prim Care 6:549–553

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW (2000) Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 160:2101–2107

Dixon LB, Holoshitz Y, Nossel I (2016) Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: review and update. World Psychiatry 15:13–20

Eaton P, Lewis T, Kellett‐Wright J, Flatt A, Urasa S, Howlett W, Dekker M, Kisoli A, Rogathe J, Thornton J, McCartney J (2020). Risk factors for symptomatic HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder in adults aged 50 and over attending a HIV clinic in Tanzania. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

Filho SM, Fernandes M, Lacerda HR, de Melo HRL (2012) Frequency and risk factors for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder and depression in older individuals with HIV in northeastern Brazil. Int Psychogeriatr 24:1648–1655

Gbadamosi IT, Henneh IT, Aluko OM, Yawson EO, Fokoua AR, Koomson A, Torbi J, Olorunnado SE, Lewu FS, Yusha’u Y, Keji-Taofik ST, Biney RP, Tagoe TA (2022) Depression in sub-Saharan Africa. IBRO Neurosci Rep 12:309–322

Goin DE, Pearson RM, Craske MG, Stein A, Pettifor A, Lippman SA, Kahn K, Neilands TB, Hamilton EL, Selin A, MacPhail C, Wagner RG, Gomez-Olive FX, Twine R, Hughes JP, Agyei Y, Laeyendecker O, Tollman S, Ahern J (2020) Depression and incident HIV in adolescent girls and young women in HIV Prevention Trials Network 068: targets for prevention and mediating factors. Am J Epidemiol 189:422–432

Gray LR, Roche M, Flynn JK, Wesselingh SL, Gorry PR, Churchill MJ (2014) Is the central nervous system a reservoir of HIV-1? Curr Opin HIV AIDS 9:552–558

Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE (2010) Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care 22:630–639

Grover S, Sahoo S, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A (2019) Anxiety and somatic symptoms among elderly patients with depression. Asian J Psychiatr 41:66–72

Harrison NA (2017) Brain structures implicated in inflammation-associated depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 31:221–248

Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M (2010) HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurol 75:2087–2096

Hegdahl HK, Fylkesnes KM, Sandoy IF (2016) Sex differences in HIV prevalence persist over time: evidence from 18 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 11:e0148502

Howorth K, Paddick SM, Rogathi J, Walker R, Gray W, Oates LL, Andrea D, Safic S, Urasa S, Haule I, Dotchin C (2019) Conceptualization of depression amongst older adults in rural Tanzania: a qualitative study. Int Psychogeriatr 31:1473–1481

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2016) Global burden of disease study 2016. Accessed 10 Jul 2020. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

Johnson JG, Rabkin JG, Lipsitz JD, Williams JB, Remien RH (1999) Recurrent major depressive disorder among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative intravenous drug users: findings of a 3-year longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry 40:31–34

Kang HJ, Kim SY, Bae KY, Kim SW, Shin IS, Yoon JS, Kim JM (2015) Comorbidity of depression with physical disorders: research and clinical implications. Chonnam Med J 51:8–18

Kellett-Wright J, Flatt A, Eaton P, Urasa S, Howlett W, Dekker M, Kisoli A, Duijinmaijer A, Thornton J, McCartney J, Yarwood V, Irwin C, Mukaetova-Ladinska E, Akinyemi R, Lwezuala B, Gray WK, Walker RW, Dotchin CL, Makupa P, Paddick SM (2021) Screening for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) in adults aged 50 and over attending a government HIV clinic in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Comparison of the International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) and IDEA Six Item Dementia Screen. AIDS Behav 25:542–553

Lee B, Kaaya SF, Mbwambo JK, Smith-Fawzi MC, Leshabari MT (2008) Detecting depressive disorder with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 in Tanzania. Int J Soc Psychiatry 54:7–20

Marwick KF, Kaaya SF (2010) Prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in HIV-positive outpatients in rural Tanzania. AIDS Care 22:415–419

Meffert SM, Neylan TC, McCulloch CE, Maganga L, Adamu Y, Kiweewa F, Maswai J, Owuoth J, Polyak CS, Ake JA, Valcour VG (2019) East African HIV care: depression and HIV outcomes. Glob Ment Health (camb) 6:e9

Mudra Rakshasa-Loots A, Whalley HC, Vera JH, Cox SR (2022) Neuroinflammation in HIV-associated depression: evidence and future perspectives. Mol Psychiatry 27:3619–3632

Munoz-Moreno JA, Fumaz CR, Ferrer MJ, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Molto J, Negredo E, Clotet B (2009) ’Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with efavirenz: prevalence, correlates, and management. A Neurobehavioral Review’, AIDS Rev 11:103–109

Nanni MG, Caruso R, Mitchell AJ, Meggiolaro E, Grassi L (2015) Depression in HIV infected patients: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17:530

Nyirenda M, Chatterji S, Rochat T, Mutevedzi P, Newell ML (2013) Prevalence and correlates of depression among HIV-infected and -affected older people in rural South Africa. J Affect Disord 151:31–38

Olagunju AT, Adeyemi JD, Ogbolu RE, Campbell EA (2012) A study on epidemiological profile of anxiety disorders among people living with HIV/AIDS in a sub-Saharan Africa HIV clinic. AIDS Behav 16:2192–2197

Olisah VO, Adekeye O, Sheikh TL (2015) Depression and CD4 cell count among patients with HIV in a Nigerian University Teaching Hospital. Int J Psychiatry Med 48:253–261

Olley BO, Seedat S, Stein DJ (2006) Persistence of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa: a 6-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res 61:479–484

Organisation, The World Health (2017) "United Republic of Tanzania - Mental Health Atlas 2017 Member State Progile." In Mental Health Atlas 2017

Organisation, The World Health (2020) Depression - Key Facts', The World Health Organisation. Accessed 16 May 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

Orlando M, Burnam MA, Beckman R, Morton SC, London AS, Bing EG, Fleishman JA (2002) Re-estimating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a nationally representative sample of persons receiving care for HIV: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 11:75–82

Osimo EF, Baxter LJ, Lewis G, Jones PB, Khandaker GM (2019) Prevalence of low-grade inflammation in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of CRP levels. Psychol Med 49:1958–1970

Peus D, Newcomb N, Hofer S (2013) Appraisal of the Karnofsky performance status and proposal of a simple algorithmic system for its evaluation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 13:72

Pirrone V, Libon DJ, Sell C, Lerner CA, Nonnemacher MR, Wigdahl B (2013) Impact of age on markers of HIV-1 disease. Future Virol 8:81–101

Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, Rahman A (2007) No health without mental health. Lancet 370:859–877

Rabkin JG, Johnson J, Lin SH, Lipsitz JD, Remien RH, Williams JB, Gorman JM (1997) Psychopathology in male and female HIV-positive and negative injecting drug users: longitudinal course over 3 years. AIDS 11:507–515

Rodkjaer L, Laursen T, Christensen NB, Lomborg K, Ostergaard L, Sodemann M (2011) Changes in depression in a cohort of Danish HIV-positive individuals: time for routine screening. Sex Health 8:214–221

Rourke SB, Halman MH, Bassel C (1999) Neurocognitive complaints in HIV-infection and their relationship to depressive symptoms and neuropsychological functioning. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 21:737–756

Sarfo FS, Jenkins C, Singh A, Owolabi M, Ojagbemi A, Adusei N, Saulson R, Ovbiagele B (2017) Post-stroke depression in Ghana: characteristics and correlates. J Neurol Sci 379:261–265

Sokoya OO, Baiyewu O (2003) Geriatric depression in Nigerian primary care attendees. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 18:506–510

Steger MF, Kashdan TB (2009) Depression and everyday social activity, belonging, and well-being. J Couns Psychol 56:289–300

Sumari-de Boer M, Schellekens A, Duinmaijer A, Lalashowi JM, Swai HJ, de Mast Q, van der Ven A, Kinabo G (2018) ’Efavirenz is related to neuropsychiatric symptoms among adults, but not among adolescents living with human immunodeficiency virus in Kilimanjaro. Tanzania’, Trop Med Int Health 23:164–172

Sweetland AC, Kritski A, Oquendo MA, Sublette ME, Norcini Pala A, Silva LRB, Karpati A, Silva EC, Moraes MO, Silva J, Wainberg ML (2017) Addressing the tuberculosis-depression syndemic to end the tuberculosis epidemic. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 21:852–861

Talman A, Bolton S, Walson JL (2013) Interactions between HIV/AIDS and the environment: toward a syndemic framework. Am J Public Health 103:253–261

Thames AD, Kim MS, Becker BW, Foley JM, Hines LJ, Singer EJ, Heaton RK, Castellon SA, Hinkin CH (2011) Medication and finance management among HIV-infected adults: the impact of age and cognition. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 33:200–209

Trangenstein PJ, Morojele NK, Lombard C, Jernigan DH, Parry CDH (2018) Heavy drinking and contextual risk factors among adults in South Africa: findings from the International Alcohol Control study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 13:43

Tsai AC (2014) Reliability and validity of depression assessment among persons with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 66:503–511

UNAIDS (2014) People aged 50 years and older. In The Gap Report 2014

UNAIDS (2018) United Republic of Tanzania. UNAIDS. Accessed 06 Oct 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/unitedrepublicoftanzania.

UNAIDS (2019) Global HIV & AIDS Statistics - 2019 fact sheet. Accessed 03 May 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

Wagner GJ, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Dickens A, Nakasujja N, Okello E, Luyirika E, Musisi S (2012) Depression and its relationship to work status and income among HIV clients in Uganda. World J AIDS 2:126–134

Wenzlaff RM, Bates DE (1998) Unmasking a cognitive vulnerability to depression: how lapses in mental control reveal depressive thinking. J Pers Soc Psychol 75:1559–1571

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients and family members who took part in this study. We also appreciate the help of the entire clinical staff team and volunteers of the Mawenzi Regional Referral Hospital Care and Treatment Centre (CTC) and of the hospital management in enabling the smooth running of the study.

Funding

This study was funded by Grand Challenges Canada (grant number 0086–04) and Newcastle University Master’s in Research Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SMP, SU, WKG, RW, CD, EBM-L, MD, WH, and SU led on the study conception and design. SMP supervised acquisition of data and trained the team. JR, AD, AK, PM, and BL developed different aspects of the clinical protocol and collected/supervised clinical data. SMP, WKG, and DD performed data analysis and interpretation. DD and OS completed the first draft, supervised by SMP. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript and gave their approval of the version submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Granted by the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research and Kilimanjaro Christian Medical College Research Ethics Committee (No. 896).

Consent to participate

Verbal and written information was given to each participant before informed consent was obtained. If participants lacked capacity to consent, assent was sought from the next of kin. Consent was rechecked at each follow-up visit.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was gained from all participants for their anonymous data to be published.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Damneek Dua and Oliver Stubbs contributed equally to this paper.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dua, D., Stubbs, O., Urasa, S. et al. The prevalence and outcomes of depression in older HIV-positive adults in Northern Tanzania: a longitudinal study. J. Neurovirol. 29, 425–439 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-023-01140-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-023-01140-4