Abstract

We report the effects of supercharging reagents dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) and m-nitrobenzyl alcohol (m-NBA) applied to untargeted peptide identification, with special emphasis on non-tryptic peptides. Peptides generated from a mixture of five standard proteins digested with trypsin, elastase, or pepsin were separated with nanoflow liquid chromatography using mobile phases modified with either 5 % DMSO or 0.1 % m-NBA. Eluting peptides were ionized by online electrospray and sequenced by both CID and ETD using data-dependent MS/MS. Statistically significant improvements in peptide identifications were observed with DMSO co-solvent. In order to understand this observation, we assessed the effects of supercharging reagents on the chromatographic separation and the electrospray quality. The increase in identifications was not due to supercharging, which was greater for the 0.1 % m-NBA co-solvent and not observed for the 5.0 % DMSO co-solvent. The improved MS/MS efficiency using the DMSO modified mobile phase appeared to result from charge state coalescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is a robust, fast, and sensitive analytical method that has transformed the field of proteomics [1, 2]. “Shotgun” or “bottom-up” proteomics involves isolation of the entire protein complement of a biological system followed by digestion into smaller fragments with a protease. Peptides are then subject to several dimensions of separation by liquid chromatography (LC) [3], the last of which is coupled directly to electrospray-ionization (ESI) MS/MS [4]. Shotgun proteomics has been used to quantify the entire complement of proteins expressed by yeast [5].

Peptides for proteomic analysis are often generated exclusively by trypsin because it produces high peptide yield and has high specificity for the positively charged amino acid residues arginine and lysine [6]. Tryptic peptides have desirable length and charge characteristics for identification by collision induced dissociation (CID), which produces b- and y-ion series [7]. Digestion with trypsin alone, however, only covers 11.9 % of the non-redundant amino acid sequences (NRAAS) [8]. By using a combination of five commercially available proteases, coverage of NRAAS increased to 25.5 % [8], which highlights the value of using alternative proteases even though they produce suboptimal peptides for traditional MS/MS identification.

Electron-transfer dissociation (ETD) is a complementary fragmentation method that forms c- and z-ion in a manner that is less dependent on the peptide sequence [9]. However, ETD is inefficient with low intensity and/or low charge state precursors. Although the ETD efficiency improves when combined with a resonance excitation after the ion–ion reaction (supplemental activation) [10], the ability to supercharge precursors is expected to dramatically improve ETD efficiencies.

The charge state and intensity of peptide ions is determined at the point of ESI by the competition of several variables including: instrument settings [11], chemical properties of the analyte and mobile phase (e.g., peptide pI, mobile phase pH) [12], ion suppression of co-eluting analytes [13], and mobile phase flow rate [14]. Long before ESI was applied to macromolecules, Lord Raleigh predicted that the maximum extent of charging, zR, of charging possible for a spherical droplet of radius, R, correlates to the surface tension, γ, of the liquid according to the relationship [15]: Total charge = ZR e = 8π(ε0γR3)1/2.

Where e and ε0 are constants pertaining to the elementary charge and the permittivity of free space, respectively. Several groups have identified molecules that result in “supercharging” of polymers and intact proteins. Iavarone and Williams first demonstrated the charge enhancement of meta-nitrobenzyl alcohol (m-NBA) for intact proteins [16, 17]. The charge enhancement of m-NBA and other supercharging reagents during ESI is especially complementary to ETD fragmentation. Addition of 0.1 % m-NBA was shown to enhance charging and, therefore, ETD fragmentation of peptides derived from BSA and β-casein [18]. Addition of m-NBA improved top down H/D exchange with ETD of protein structure yielding 1.3 amino acid resolution in real time [19] and top-down ESI with electron-capture dissociation (ECD) was also improved [20]. Additional supercharging reagents have been identified. In 2002, Iavarone and Williams reported the use of several small molecules, including dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and even glycerol [16, 17]. Recently, Valeja et al. reported several small molecule organic reagents that effect ESI charge state of intact protein and chromatographic retention during LC/MS [21]. Lomeli et al. also report the extent of charge enhancement resulting from a screen of several aromatic compounds and sulfolane [22]. These researchers reported that sulfolane forms adducts in the supercharging process, and sulfolane adducts were recently investigated in more detail [23]. Despite extensive application of supercharging reagents for ESI of intact proteins, so far only Kjeldsen et al. applied m-NBA to enhance the charge state of peptides for ETD fragmentation and identification [18].

Although the charge enhancing phenomena of these reagents correlates well with the Raleigh equation in many measurements, the complex chemical environment at the end of the droplet lifetime produces deviations from theory [24, 25]. Factors affecting the observed analyte charging result from the high-boiling supercharging reagent that becomes enriched in the late stage of the desolvating droplet and results in non-spherical droplets [26], and protein chemical and/or thermal denaturation [27]. Additionally, the gas-phase proton affinity of both analyte and solvent must be considered [28].

Here we present an exploration of charge-enhancing reagents, DMSO and m-NBA, for improved peptide identification by LC-MS/MS. DMSO was selected because Valeja et al. recently observed, in addition to supercharging, improved chromatography of intact protein during reversed-phase with a C5 stationary phase [21]. m-NBA was selected because Kjeldsen et al. previously reported increased ETD quality with this co-solvent [18]. Sulfolane was not used since we already had a representative sulfoxide compound [23]. We were particularly interested in the effect of charge enhancement for peptides generated from alternative proteases that do not have an amino acid with a basic side chain at the C-terminus. We hypothesized that high charge states produced from ESI with DMSO and m-NBA may improve the sensitivity of non-tryptic peptide identification when used in combination with ETD. To assess the practical application of these reagents for LC-MS/MS, the mobile phases used for reversed-phase nano liquid chromatography were modified with supercharging reagents DMSO and m-NBA in a manner similar to Kjeldsen et al [18]. Mobile phase properties are known to affect chromatographic resolution and retention [29, 30], and indeed some differences were observed in the chromatography. Peptides produced by various protease digestions (i.e., trypsin, elastase, or pepsin) of a five protein mixture were used to assess effects of the modified mobile phases on chromatographic separation, precursor ion effects, and ultimately, the number of peptide identifications. The samples were analyzed with a combination of CID and ETD [31, 32], and the data were searched with MS-GFDB, which allows searching of CID/ETD pairs [33]. The co-solvent, DMSO, markedly improved the number of peptide identifications compared with formic acid alone for all three proteases.

2 Experimental

2.1 Samples and Solutions

Acetonitrile (ACN) and formic acid (FA) Optima grade were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). TCEP (BondBreaker) was from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Trizma, iodoacetamide (IAA), sodium deoxycholate (SDC) dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), meta-nitrobenzyl alcohol (m-NBA), and angiotensin I were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All chemicals were of the highest purity possible and were used without further purification. Peptides from a standard mixture of five proteins (bovine serum albumin (BSA), α-casein (S1 and S2), β-casein, lysozyme C, and hemoglobin [α and β]) were digested separately by pepsin, elastase, or trypsin as described previously [34], with the exception that pepsin digestion was performed in 0.1 % FA without sodium deoxycholate. The digests were stored lyophilized at −80 ° C. For MS/MS experiments, the amount injected was 16 ng. Full scan MS experiments were performed with three quantities of analyte spanning an order of magnitude, 16, 80, and 160 ng.

2.2 Liquid Chromatography

Control mobile phase A consisted of 0.2 % FA with 5 % ACN in water, and control mobile phase B consisted of 0.2 % FA with 95 % ACN in water. In addition to the controls, both mobile phases, A and B, were also modified with either 5 % DMSO or 0.1 % m-NBA. The presence of 5 % ACN in mobile phase A assisted with m-NBA dissolution.

2.3 nLC-MS/MS

Lyophilized peptides were resuspended in 0.2 % FA in water, and were separated over a 75 μm i.d. × 12 cm capillary column packed in-house with 5 μm Phenomenex Luna C18 particles. An Agilent 1200 series pump was used to generate a flow of 0.11 mL/min, which was split 1:500 to ~250 nL/min. Separation was achieved with a gradient from 100 % to 70 % phase A over 60 min. Mobile phase B was then increased to 95 % over 10 min, and the column was flushed for 10 minutes, followed by re-equilibration with 100 % A at 400 nL/min for 10 minutes. MS data were collected during the flush and re-equilibration to ensure consistent column regeneration, resulting in a total of 90 min of data collection for each run. The eluent was directly electrosprayed at 2.1 kV into an LTQ XL with ETD (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). To ensure effective desolvation of high-boiling supercharging reagents, the ion transfer tube temperature was set to 275 °C. Full-scan-only experiments were collected from m/z 350 to 2000 using the enhanced scan rate, which produces resolution sufficient to resolve the isotope distribution of a +3 charge state ion. For data-dependent peptide identification experiments, the top five most abundant precursor ions determined by a precursor ion scan from m/z 300 to 2000 were selected for “zoom” scans (+/− 5 DA) at a resolution sufficient to determine precursor charge state. Charge states not equal to 1 with intensity over 1000 counts were fragmented consecutively by both CID and ETD. After collection of two fragment ion spectra, precursor m/z values were excluded for 15 s. The exclusion list size was set to 500. Activation settings were optimized by directly infusing angiotensin I at 1 pmol/μL. Infusion in each of the three different solvent systems did not show any significant differences in the optimal activation settings. ETD activation was performed using fluoranthene anions for 120 ms followed by supplemental activation to break up noncovalent gas-phase interactions [10]. CID activation was performed for 30 ms using “35 % normalized collision energy.” The automatic gain control settings were AGC Reagent = 3e5, AGC Full MS = 3e4, AGC MSN = 1e3, AGC zoom = 3e3. The instrument was operated using the Xcalibur ver. 2.0.7 software (ThermoFisher Scientific).

2.4 Data Analysis

The resulting data were analyzed by MS-GFDB [33]. Files were converted to mzXML using Trans-Proteomic Pipeline [35]. The resulting .mzXML files were searched against the Uniprot database of all bovine proteins plus common contaminants and lysozyme C from chicken, as well as the three proteases, porcine trypsin, elastase, and pepsin. The false discovery rate (FDR) was estimated using the target-decoy approach by including shuffled sequences in the search database. Database searches were performed with and without the option to merge CID and ETD fragment ion spectra from the same precursor ion [33]. In addition to the default fixed carbamidomethylation of cysteine, searches allowed variable deamidation of Q or N, and phosphorylation of S or T. Up to two variable modifications were allowed. Data from elastase and pepsin experiments were searched using “no enzyme” specificity. Precursor charge states from two to five were considered for spectra with undetermined charge. The precursor mass tolerance was set to 2.5 DA. Default parameters used were: instrument = low-resolution LCQ/LTQ; one allowed non-enzymatic terminus, and possible peptide lengths from six to 40 amino acids were considered. Only peptide spectrum matches to the standard proteins or the protease with FDR <0.01 were used for further analysis. Chromatographic retention and resolution were assessed using XCMS [36] and in-house scripts written in R [37]. Annotated MS/MS spectra were visualized using Proteowizard [38]. Spectral counts, referring to the number of times a peptide sequence was matched to an MS/MS spectrum, were used to provide an estimate of MS/MS efficiency.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Co-Solvent Effects on the Number of High Quality Peptide Identifications

To explore the improvements in peptide identifications from the use of mobile-phase additives (i.e., 5 % DMSO, 0.1 % m-NBA), we analyzed digests of a five-protein mixture containing BSA, hemoglobin, α-casein, β-casein, and lysozyme C. The mixture was digested with trypsin, elastase, or pepsin, and analyzed in triplicate by nLC-MS/MS on an LTQ mass spectrometer using consecutive activation of selected precursors by both CID and ETD fragmentation. The resulting spectra were searched as pairs. At a peptide-level false discovery rate of <0.01, the numbers of unique peptides identified under each solvent condition are given in Table 1. For each of the three different proteolytic digests, inclusion of DMSO increased the numbers of peptides identified, and for two of the three protease digestions, the results were highly significant (P value > 0.05). The observed improvement could arise from a number of variables, such as ESI charge enhancement resulting in more efficient ETD fragmentation, or effects on chromatographic retention and resolution. The contribution of each variable was assessed separately.

3.2 Effects of Co-Solvents on Chromatography

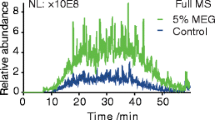

Most of the data acquisition time during the peptide identification experiments is spent determining charge state and collecting fragment ion spectra (>5 s between precursor scans). To better assess the contribution of chromatographic quality on the relative MS/MS efficiencies observed, we collected full-scan-only MS spectra. Normalized total ion chromatograms (TICs) are shown in Figure 1. Separations containing m-NBA resulted in more noise, as evidenced by the elevated baseline, as well as an apparent increase in peak height and width. Peak heights also apparently increased when the mobile phase contained 5 % DMSO. Quantitative assessment of peptide-level chromatographic resolution was achieved by generating extracted-ion chromatograms (EICs), an example of which is shown in Figure 2. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) from analyses carried out in FA only and FA plus DMSO runs were not significantly different. However, separations carried out in the presence of m-NBA resulted in wider peaks (Table 2). Figure 2 also shows how the retention time decreases due to the co-solvents. This observation prompted us to carry out a non-linear retention time alignment as a comprehensive measure of chromatographic retention (Figure 3). Separations in the presence of DMSO and m-NBA generally decreased retention times compared to the FA only control. m-NBA introduces different functional groups to the reversed-phase separation system that allow hydrogen bonding, aromatic pi-stacking/pi-cation interactions, and ionic interactions with the nitro group. Together these properties appear to decrease the quality of chromatography in the presence of m-NBA.

Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) for the +1, +2, and +3 charge states of the elastic peptide TEDELQDKIHPF, illustrating the relative charge distributions produced during ESI for three mobile phases: 0.2 % FA only (top, black), 0.2 % FA + 5.0 % DMSO (middle, red), or with 0.2 % FA + 0.1 % m-NBA (bottom, blue)

Global effects of supercharging reagents DMSO and m-NBA on chromatographic peptide retention during reversed-phase nano LC-ESI-MS/MS. Peaks identified in all samples were aligned and the median observed retention was chosen as the zero point. Both DMSO and m-NBA modified mobile phases generally result in reduced retention times compared with the control, 0.2 % FA alone (black). At high concentrations of ACN, the DMSO caused increased retention (red), whereas the m-NBA continued to reduce retention times (blue). The solid grey line gives the gradient profile, and the dashed lines represent the moving average of retention time deviation for each condition

3.3 Tandem Mass Spectrum Quality

The quality of MS/MS spectra was assessed for both CID and ETD fragmentation of the doubly charged precursor ion and the triply charged precursor ion for the elastic peptide, TEDELQDKIHPF (Figure 4). As expected, a significant improvement in the ETD fragment ion series resulting from the triply charged precursor ion as compared to the doubly charged precursor ion was observed [9]. The use of supplemental activation resulted in significant populations of b- and y-ions in the ETD fragment ion spectra [10].

MS/MS spectra produced from the fragmentation of the doubly and triply charged precursor for the elastic peptide TEDELQDKIHPF. CID of the doubly charged precursor produced a rich fragment ion spectra, but CID of the triply charged precursor resulted in few fragment ions. In contrast, ETD of the doubly charged precursor produced a weak ladder of fragment ions, but ETD of the triply charged precursor produced a nearly complete sequence ladder of c- and z*- ion pairs. Supplemental activation used with ETD also resulted in b-, y-, ions that aided in sequence determination

Interestingly, the triply charged precursor ion was poorly fragmented by CID, and the spectra did not match the sequence below 1 % FDR. Thus, for this example, the peptide identification was of high quality for the doubly charged precursor ion by CID and for the triply charged precursor ion by ETD, which highlights the complementary nature of the two approaches. To examine whether in each co-solvent more identifications were made by ETD or CID, we searched CID and ETD spectra separately (Table 3, Figure 5). MS-GFDB can either score CID and ETD spectra separately, or merge the CID and ETD spectra from the same precursor into a summed, scored spectrum [33]. When the spectra were searched separately, DMSO afforded increased numbers of peptides identified in both CID and ETD, whereas fewer peptides were identified from the m-NBA co-solvent compared with FA alone. Similar results were obtained from the searches in which the CID and ETD spectra were merged. In addition, dramatic gains in identifications were achieved using the merged search for non-tryptic peptides.

Comparison of unique peptide counts for each protease and each mobile phase condition. The number of unique peptides identified by CID (blue) is compared with the number of unique peptides identified by ETD (red). The sum of unique peptides identified from both CID and ETD spectra combined after the database search (yellow) is also compared with the number of unique peptides identified using the option to merge spectra from the same precursor before computing the score histogram (green). For non-tryptic peptides, the merged scoring produced dramatic increases in the number of unique peptides that are identified. The error bars are +/− one standard deviation of the average of three independent experiments

3.4 Effects on Peptide Charge State

The effects of DMSO and m-NBA on peptide precursor charge state distributions were assessed with data from full-scan-only experiments. Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) for all possible charge states of peptides identified from MS/MS experiments were analyzed. Representative EICs for the singly, doubly, and triply charged precursor ions of an elastic peptide (TEDELQDKIHPF) are shown in Figure 2. Peaks from EICs were integrated and areas for each charge state were used to calculate the charge distribution for four peptides containing zero, one, two, or three basic side chains (Table 4). For 0.2 % FA alone, the average charge state was centered near the number of basic functional groups present within the peptide, but a significant portion of the peptide also was found with one more charge. When m-NBA was added, most of the peptide carried the additional charge. With DMSO as the co-solvent, the charge state distribution coalesced to the charge state corresponding to the number of basic residues. Results from experiments on intact proteins also showed decreases in charge state relative to control at low concentrations of DMSO [39].

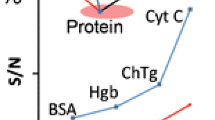

To globally assess the effects of the charge state distributions produced using each mobile phase condition on overall quality of data produced, we assessed the number of unique peptides identified and total spectral counts for each peptide at each charge state from each mobile phase condition (Table 5). Both DMSO and m-NBA co-solvents resulted in nearly double the total ion signal (as calculated from EICs generated for all charge states summed). However, addition of DMSO resulted in a significant increase in the number of peptides identified. This increase appeared to be due to a significant signal enhancement for the most probable charge state. Thus, DMSO causes charge state coalescence into a single charge state, which translates into simpler precursor spectra resulting in improved MS/MS data.

For all peptides, the m-NBA modified mobile phase resulted in the highest precursor charge states. m-NBA was able to supercharge peptides to charge states greater than the number of basic functional groups present (i.e., R, K, H, and the n-terminal). For example, ESI of Glu-fib, EGVNDNEEGFFSAR, resulted in almost exclusively a doubly charged precursor ion for 5.0 % DMSO and the FA only control, but with 0.1 % m-NBA, the precursor ion was mostly triply charged. This peptide has only one basic residue and four acidic residues. The basic residue and the N-terminus are expected to carry positive charges; however, the third site of charging in the m-NBA co-solvent is not obvious. The utility of m-NBA supercharging is further demonstrated by the identification of a peptic peptide that did not contain any positive side chains (peptide 0 in Table 2), which was only sequenced in the analysis carried out with m-NBA added (Figure 6). In fact, 17 peptic peptides that did not contain R, K, or H residues were identified using m-NBA as the co-solvent. Therefore, supercharging, at least with peptide analytes, can cause peptide precursor ions to have a number of charges greater than the number of basic functional groups present. This observation is in contrast to speculation by Douglass and Venter that the number of basic residues may limit the extent of supercharging [23].

MS/MS spectra produced from the fragmentation of the doubly charged precursor of the peptic peptide: SDIPNPIGSENS, which bears no positive charged side chains. (a) CID fragmentation results in a spectra dominated by the y 9 ion, which corresponds to fragmentation at proline. (b) ETD with supplemental activation results in fragments that complement the CID spectra in the high mass region

To assess the potential benefit from m-NBA-mediated charge enhancement, a theoretical digest was carried out for each of the proteases on the five protein mixture using MS-digest in Protein Prospector (www.prospector.ucsf.edu). Peptides produced from trypsin digestion can only lack a positive side chain if they arise from the protein C-terminus. In fact, only 1 % of theoretical tryptic peptides from the five protein mixture lack any basic amino acid side chains. Elastase and pepsin, however, are predicted to result in more peptides lacking possible positive charges, 14 % and 12 %, respectively.

4 Conclusions

Here we present an analysis of factors relevant to the application of supercharging reagents DMSO and m-NBA for peptide identification by nano-ESI-LC-MS/MS. Consistent with previous reports, the m-NBA modified mobile phase produced extensive supercharging of peptides. However, the extent of charge enhancement did not correlate with the number of peptide identifications even with sequential fragmentation with both CID and ETD. The addition of m-NBA was very important for obtaining better ETD spectra from peptides that did not have many side chains that could carry a positive charge and, therefore, may find use in targeted experiments. For data-dependent, untargeted experiments, however, the lower chromatographic quality and the broad distribution of highly charged precursors achieved with the m-NBA co-solvent obviated any improvements in total numbers of high quality peptide identifications. Kjeldsen et al. also observed chromatographic broadening but did not observe a decrease in the number of identifications from a digest of BSA [18]. Chromatographic broadening is expected to adversely affect analyses of more complex mixtures but may not affect the analysis of simple ones. In addition, the broad precursor charge state distribution results in several precursor ions for each peptide in the complex mixture, resulting in a lower signal to noise ratio. Further, highly charged precursors result in multiply charged fragment ions that are difficult to resolve on low resolution ion-trap instruments.

Using a combination of ion mobility and circular dichroism, Sterling et al. showed recently that supercharging reagents act as chemical denaturants for intact proteins, and that the higher charge species are more unfolded [27]. In the case of peptides, it is likely that they are completely unfolded and that the charge state will depend on the number of basic residues as well as the length of the peptide. Therefore, we postulate that the number of peptide microstates allowed in the electrosprayed droplet containing DMSO is limited to only the most favorable extent of charging allowed by each individual peptide sequence and length. Thus, although supercharging was observed with the m-NBA, it was not observed with DMSO.

It is interesting to speculate on the reasons for the marked charge coalescence with DMSO. Visual comparison of the electrospray under each tested mobile phase condition showed that the most stable spray was achieved across all parts of the gradient with DMSO-modified mobile phases. According to the Raleigh equation, spray stability could also contribute to more uniform droplet sizes, which might translate directly into more uniform charge states. Finally, it is possible that DMSO acts to promote desolvation efficiency and increase the total signal at a favorable charge state.

For both tryptic and non-tryptic peptides, DMSO increases total MS/MS productivity apparently because of charge state coalescence, which results in more peptide precursor signal at a predominant charge state. DMSO is expected to be particularly useful when complex peptide mixtures are analyzed using data-dependent acquisition approaches. Therefore, we expect this simple mobile phase addition to be widely adopted in bottom-up peptide identification experiments, regardless of protease and fragmentation. Further gains are expected when this strategy is combined with high resolution mass spectrometry.

References

Sleno, L., Volmer, D.A.: Ion activation methods for tandem mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 39, 1091–1112 (2004)

Ong, S.-E., Mann, M.: Mass spectrometry-based proteomics turns quantitative. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 252–262 (2005)

Motoyama III, A.J.R.Y.: Multidimensional LC separations in shotgun proteomics. Anal. Chem. 80, 7187–7193 (2008)

Fenn, J., Mann, M., Meng, C., Wong, S., Whitehouse, C.: Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science 246, 64–71 (1989)

de Godoy, L.M.F., Olsen, J.V., Cox, J., Nielsen, M.L., Hubner, N.C., Frohlich, F., Walther, T.C., Mann, M.: Comprehensive mass-spectrometry-based proteome quantification of haploid versus diploid yeast. Nature 455, 1251–1254 (2008)

Burkhart, J. M., Schumbrutzki, C., Wortelkamp, S., Sickmann, A., Zahedi, R. P.: Systematic and quantitative comparison of digest efficiency and specificity reveals the impact of trypsin quality on MS-based proteomics. J. Proteom. 75, 1454–1462 (2012)

Tabb, D.L., Smith, L.L., Breci, L.A., Wysocki, V.H., Lin, D., Yates, J.R.: Statistical characterization of ion trap tandem mass spectra from doubly charged tryptic peptides. Anal. Chem. 75, 1155–1163 (2003)

Swaney, D.L., Wenger, C.D., Coon, J.J.: Value of using multiple proteases for large-scale mass spectrometry-based proteomics. J. Proteom. Res. 9, 1323–1329 (2010)

Syka, J.E.P., Coon, J.J., Schroeder, M.J., Shabanowitz, J., Hunt, D.F.: Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 9528–9533 (2004)

Swaney, D.L., McAlister, G.C., Wirtala, M., Schwartz, J.C., Syka, J.E.P., Coon, J.J.: Supplemental activation method for high-efficiency electron-transfer dissociation of doubly protonated peptide precursors. Anal. Chem. 79, 477–485 (2006)

Loo, J.A., Udseth, H.R., Smith, R.D., Futrell, J.H.: Collisional effects on the charge distribution of ions from large molecules, formed by electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2, 207–210 (1988)

Kamel, A.M., Brown, P.R., Munson, B.: Effects of mobile-phase additives, solution pH, ionization constant, and analyte concentration on the sensitivities and electrospray ionization mass spectra of nucleoside antiviral agents. Anal. Chem. 71, 5481–5492 (1999)

Mallet, C.R., Lu, Z., Mazzeo, J.R.: A study of ion suppression effects in electrospray ionization from mobile phase additives and solid-phase extracts. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 18, 49–58 (2004)

Ficarro, S.B., Zhang, Y., Lu, Y., Moghimi, A.R., Askenazi, M., Hyatt, E., Smith, E.D., Boyer, L., Schlaeger, T.M., Luckey, C.J., Marto, J.A.: Improved electrospray ionization efficiency compensates for diminished chromatographic resolution and enables proteomics analysis of tyrosine signaling in embryonic stem cells. Anal. Chem. 81, 3440–3447 (2009)

Rayleigh, L.: On the equilibrium of liquid conducting masses charged with electricity. Phils. Mag. 14, 184–186 (1882)

Iavarone, A.T., Williams, E.R.: Supercharging in electrospray ionization: effects on signal and charge. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 219, 63–72 (2002)

Iavarone, A.T., Williams, E.R.: Mechanism of charging and supercharging molecules in electrospray ionization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 2319–2327 (2003)

Kjeldsen, F., Giessing, A.M., Ingrell, C.R., Jensen, O.N.: Peptide sequencing and characterization of post-translational modifications by enhanced ion-charging and liquid chromatography electron-transfer dissociation tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 79, 9243–9252 (2007)

Sterling, H.J., Williams, E.R.: Real-time hydrogen/deuterium exchange kinetics via supercharged electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 82, 9050–9057 (2010)

Yin, S., Loo, J.A.: Top-down mass spectrometry of supercharged native protein–ligand complexes. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 300, 118–122 (2011)

Valeja, S.G., Tipton, J.D., Emmett, M.R., Marshall, A.G.: New reagents for enhanced liquid chromatographic separation and charging of intact protein ions for electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 82, 7515–7519 (2010)

Lomeli, S.H., Peng, I.X., Yin, S., Ogorzalek Loo, R.R., Loo, J.A.: New reagents for increasing ESI multiple charging of proteins and protein complexes. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 21, 127–131 (2010)

Douglass, K.A., Venter, A.R.: Investigating the role of adducts in protein supercharging with sulfolane. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 23, 489–497 (2012)

Hogan, J.C.J., Biswas, P.: Monte Carlo simulation of macromolecular ionization by nanoelectrospray. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 19, 1098–1107 (2008)

Wilm, M.: Principles of electrospray ionization. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, 1–8 (2011)

Ahadi, E., Konermann, L.: Modeling the behavior of coarse-grained polymer chains in charged water droplets: implications for the mechanism of electrospray ionization. J. Phys. Chem. B (2011)

Sterling, H.J., Daly, M.P., Feld, G.K., Thoren, K.L., Kintzer, A.F., Krantz, B.A., Williams, E.R.: Effects of supercharging reagents on noncovalent complex structure in electrospray ionization from aqueous solutions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 21, 1762–1774 (2010)

Ogorzalek Loo, R.R., Smith, R.D.: Proton transfer reactions of multiply charged peptide and protein cations and anions. J. Mass Spectrom. 30, 339–347 (1995)

Coulier, L., Bas, R., Jespersen, S., Verheij, E., van der Werf, M.J., Hankemeier, T.: Simultaneous quantitative analysis of metabolites using ion-pair liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 78, 6573–6582 (2006)

Gustavsson, S.Å., Samskog, J., Markides, K.E., Långström, B.: Studies of signal suppression in liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry using volatile ion-pairing reagents. J. Chromatogr. A 937, 41–47 (2001)

Swaney, D.L., McAlister, G.C., Coon, J.J.: Decision tree-driven tandem mass spectrometry for shotgun proteomics. Nat. Methods 5, 959–964 (2008)

Kim, M.-S., Zhong, J., Kandasamy, K., Delanghe, B., Pandey, A.: Systematic evaluation of alternating CID and ETD fragmentation for phosphorylated peptides. Proteomics 11, 2568–2572 (2011)

Kim, S., Mischerikow, N., Bandeira, N., Navarro, J.D., Wich, L., Mohammed, S., Heck, A.J.R., Pevzner, P.A.: The generating function of CID, ETD and CID/ETD pairs of tandem mass spectra: applications to database search. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 2840–2852 (2010)

Lin, Y., Zhou, J., Bi, D., Chen, P., Wang, X., Liang, S.: Sodium-deoxycholate-assisted tryptic digestion and identification of proteolytically resistant proteins. Anal. Biochem. 377, 259–266 (2008)

Keller, A., Eng, J., Zhang, N., Li, X.-j., Aebersold, R.: A uniform proteomics MS/MS analysis platform utilizing open XML file formats. Mol. Syst. Biol. 1(2005)

Smith, C.A., Want, E.J., Tong, G.C., Abagyan, R., Siuzdak, G.: XCMS: Processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal. Chem. 78, 779–787 (2006)

Development Core Team: A language and environment for statistical computing. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/ (2012)

Kessner, D., Chambers, M., Burke, R., Agus, D., Mallick, P.: ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics 24, 2534–2536 (2008)

Sterling, H.J., Prell, J.S., Cassou, C.A., Williams, E.R.: Protein conformation and supercharging with DMSO from aqueous solution. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 22, 1178–1186 (2011)

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge financial support for this work was from the Bruno Zimm Scholar fund (E.A.K.). J.G.M. was supported by NIH training grant T32EB009380. The authors acknowledge Xinning Jiang for technical assistance and Nuno Bandeira for helpful comments. They acknowledge the UCSD Pathology Department for instrument usage. They thank the referees for their detailed comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meyer, J.G., A. Komives, E. Charge State Coalescence During Electrospray Ionization Improves Peptide Identification by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 23, 1390–1399 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-012-0404-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-012-0404-0