Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is revolutionizing healthcare delivery. The aim of the study was to reach consensus among experts on the possible applications of telemedicine in colorectal surgery. A group of 48 clinical practice recommendations (CPRs) was developed by a clinical guidance group based on coalescence of evidence and expert opinion. The Telemedicine in Colorectal Surgery Italian Working Group included 54 colorectal surgeons affiliated to the Italian Society of Colo-Rectal Surgery (SICCR) who were involved in the evaluation of the appropriateness of each CPR, based on published RAND/UCLA methodology, in two rounds. Stakeholders’ median age was 44.5 (IQR 36–60) years, and 44 (81%) were males. Agreement was obtained on the applicability of telemonitoring and telemedicine for multidisciplinary pre-operative evaluation. The panel voted against the use of telemedicine for a first consultation. 15/48 statements deemed uncertain on round 1 and were re-elaborated and assessed by 51/54 (94%) panelists on round 2. Consensus was achieved in all but one statement concerning the cost of a teleconsultation. There was strong agreement on the usefulness of teleconsultation during follow-up of patients with diverticular disease after an in-person visit. This e-consensus provides the boundaries of telemedicine in colorectal surgery in Italy. Standardization of infrastructures and costs remains to be better elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) marked the start of a new era in many fields of medicine. Thousands of studies on COVID-19 epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, control and impact on health resources have stormed the last year medical literature [1].

A recent survey of 1051 colorectal surgery divisions from 84 countries highlighted global changes in diagnostic and therapeutic colorectal cancer practices [2]. More than two thirds of respondents (71%) reported delays in endoscopy, radiology, surgery, histopathology, or prolonged chemoradiation therapy-to-surgery intervals. The worldwide suspended in-person elective clinical activities promoted a further increase in the use of internet and social media, yet well-known powerful tools to increase engagement and participation of patients with colorectal diseases [3].

Telemedicine (or telehealth) is the distribution of remote clinical services, including diagnosis, monitoring, and prescribing therapies by means of health-related services using information and communications technology [4].

In line with a recent consensus exercise defining the role of telemedicine in proctology [5], the aim of the present study was to reach a consensus on its application in the colorectal field for screening purposes, diagnosis, follow-up, and surgical decision-making.

Methods

A literature search was performed using PubMed and evidence-based medicine reviews between January 1990 and September 2020. The search strategy included the following combination of terms: (colorectal) and (telemedicine or telehealth or teleconsultation).

After balancing clinical experience and common understanding of the evidence, group discussion led to shared judgments about recommendations for using telemedicine in colorectal practice. In the absence of data from Oxford level I–IV studies, the guided development group, composed of the steering committee and external advisors (see Acknowledgement section), produced a final list of clinical practice recommendations (CPRs). The group was responsible for the selection of the different topics to be incorporated, and items were finalized after discussion through e-mails and teleconferences.

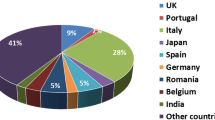

Fifty-four experts (Telemedicine in Colorectal Surgery Italian Working Group, nominated by the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery) on the basis of both previously published research and clinical experience in the field of colorectal practice, were invited to join the e-consensus. The consensus methodology was derived from the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method [6], an established approach previously used in the coloproctology field [5, 7].

Forty-eight CPRs were presented electronically using an online platform (“Online Surveys,” formerly Bristol Online Survey, developed by the University of Bristol) under 3 subheadings: “feasibility and pros/cons of telemedicine in colorectal surgery” (n = 14 statements), “clinical application of telemedicine in colorectal surgery” (n = 13 statements), and “legal and technical issues of a teleconsultation” (n = 21 statements). For each item, the consensus panelists were asked, “Does this recommendation lead to an expected health benefit (e.g., improved patient experience and functional capacity) that exceeds the expected negative consequences of its introduction (e.g., increased morbidity, anxiety, or denial of an investigation or treatment)?”.

The responses to each recommendation used a linear analog scale from 1 to 9 to assess views on the benefit-to-harm ratio. Using this scale, a score of 1–3 indicated that they expected the harm of introducing the recommendation to greatly outweigh the expected benefits, and a score of 7–9 that the expected benefits to greatly outweigh the expected harm. A middle rating of 4–6 could mean either that the harm and benefits were considered approximately equal or that the panelist was unable to make a judgment for the recommendation.

Responses were analyzed in accordance with the first phase of the RAND/UCLA guidance, with each recommendation classified as “appropriate,” “uncertain,” or “inappropriate,” according to the panelists’ median score and the level of disagreement. Indications with median scores in the range of 1–3 were classified as inappropriate, those in the range of 4–6 as uncertain, and those in the range of 7–9 as appropriate. “Disagreement” implied a lack of consensus because of polarization (defined as a > 17 rating of the indication in each extreme for a sample of 53–55 panelists) [6]. All indications rated “with disagreement,” whatever the median, were classified as uncertain.

A second round of consensus was conducted to reduce variation using the same methodology. Only statements rated “uncertain” (i.e., panel median of 4–6 or any median with disagreement) were reviewed and resubmitted for voting.

Interrater agreement in each round of consensus was calculated by the Kappa statistic, which was interpreted according to the suggestions by Landis and Koch: Poor (Kappa, 0.01–0.20), slight (0.21–0.40), fair (0.41–0.60), moderate (0.61–0.80), and substantial (0.81–1.00) [8].

Results

Fifty-four invited colorectal surgeons (male–female ratio, 4.4; median age, 44.5 [interquartile range limits, IQRL, 36–60]), members of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR), agreed to join the first round of this e-consensus (response rate 100%). Overall agreement was poor (Kappa, 0.12; Suppl. Table 1).

Feasibility and pros/cons of telemedicine in colorectal surgery

Eleven out of 14 (79%) proposed statements resulted appropriate. The percentage of agreement was ≥ 75% for 4 statements and 55–74% for 7 statements (Table 1).

The statements yielding the highest level of agreement assessed the applicability of telemonitoring (i.e., decision-making parameters and findings sent by patients to the surgeon for a prompt reassessment).

Two statements were deemed inappropriate. These concerned the exclusive use of the telemedicine during the pandemic and the possibility to perform a remote first consultation. One statement assessing the performance of post-surgical consultation remotely resulted uncertain.

Clinical application of telemedicine in colorectal surgery

Four statements were uncertain, with level of agreement ranging between 35 and 43% (Table 1). The uncertain statements explored the use of teleconsultation for diagnosis and decision-making in patients with oncological, diverticular and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

All the other statements resulted appropriate with agreement yielding 75% and above for 4 statements and 50–74% for 5 statements.

The panel strongly agreed with the usefulness of the telemedicine for multidisciplinary pre-operative evaluation of colorectal cancer patients.

Legal and technical issues of a teleconsultation

Eighteen statements resulted appropriate, while 3 were uncertain (Table 1). Level of agreement was ≥ 75% for 12 (57%) statements. The highest concerned the need of a video support allowing to share photos/videos during the teleconsultation and the need of a “key-contact” as a facilitator whenever the patient is unable to use electronic platforms.

The uncertain statement dealt with the cost of a teleconsultation as compared to a conventional visit, the use of social media as a tool for video calls, and the need of a phone call in the instance of technical problems during a teleconsultation.

Second round

Fifty-one experts (response rate, 94%) took part to the second round. The median age was 43.5 years (IQRL 35.7–60) and ten (20%) were females. Levels of agreement were similar to round 1 (Suppl. Table 1).

The fifteen statements resulting uncertain on round 1 were rephrased. Consensus was achieved in all but one statement (median, 4) concerning the cost of a teleconsultation, which should be 50% lower than a conventional visit (Table 2).

Further two statements exploring the cost of a teleconsultation and its potential to replace a conventional visit, were deemed inappropriate. A total of 13 statements were found appropriate, with the highest agreement (86%) obtained by the statement regarding the usefulness of the teleconsultation during follow-up of patients with diverticular disease after a conventional visit.

Discussion

Besides its devastating sequalae, COVID-19 pandemic has led to several ground-breaking innovations to improve patient and provider safety. Telemedicine is certainly one of them. As expressed by Watson, the integration of telemedicine into everyday clinical practice is similar to the transition from open to laparoscopic surgery, which made surgeons ‘pioneers in health care cultural change’ [9].

According to our panel, telemedicine can ease the management of colorectal diseases and its usefulness is likely to continue beyond the pandemic, with the potential to reduce waiting times in health services.

The panel voted against the use of telemedicine as first colorectal consultation or in the surgical decision-making process. Indeed, an outpatient evaluation was deemed appropriate to plan the correct surgical treatment according to the experts. In a previous consensus exercise defining the role of telemedicine in proctology [5], the majority of respondents (35/47 [74%]) recommended an in-person assessment to avoid cancer misdiagnosis. Indeed, the study highlighted poor acceptability of telemedicine as first-line assessment for the majority of proctologic disorders except for the diagnosis and management of pilonidal disease and ostomy patients. Conversely, teleconsultation was deemed appropriate for screening, pre-hospitalization and follow-up purposes.

In a recent quality improvement study evaluating patients’ satisfaction prior to endoscopy [10], 138 patients underwent an advanced endoscopic pre-procedure consultation visits by three different modalities (telemedicine [26%], traditional in-person visits [21%], or a direct access procedure [52%]). The authors failed to demonstrate any statistically significant differences between these groups. However, patients with a de novo diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer and attending a telemedicine visit had a greater satisfaction level in comparison to a direct access procedure. These results were consistent with the present study, where teleconsultation was considered appropriate for medical history collection, pre-hospitalization and interview preceding a conventional visit.

Moreover, teleconsultation was not recommended for the diagnosis and management of diverticular disease, IBD, and oncological diseases, given the high risk of misdiagnosis. Conversely, it was recommended in the management of stoma patients, in line with the results of a previous randomized controlled trial [11].

The intervening period between two teleconsultations should be shorter than that between two conventional consultations, due to the fear of a misdiagnosis that might cause significant treatment delays. For the same reason, the panel considered teleconsultation appropriate for IBD, oncological and diverticular diseases only after performance of second-line imaging modalities, colonoscopy and dosage of fecal calprotectin.

A recent survey including 374 cancer patients and 14 physicians pointed out that the majority of both patients (63.1%) and physicians (64.1%) preferred a complete in-person assessment, even if remote visits may prevent the risk of contagion [12].

Recently, Ruf et al. [13] showed the effectiveness of telehealth care through a combined setup of videoconferencing appointments attended by 88 IBD patients, with only 0.9% of visits requiring urgent medical evaluation and a non-attending rate of 2.6%. In particular, the authors demonstrated the time and cost-saving potential of telemedicine in remote/rural areas.

Further advantages were reported by Sellars et al. [14], showing that video consultation saved 6.685 traveled miles, 148 h traveling time and £1767 cost as well as a carbon dioxide emission exceeding 250.000 charges of a smartphone. Interestingly, the panel strongly agreed on the potential of telemedicine to reduce distances between geographically distant areas.

In line with previous recommendations [15,16,17], telemedicine was felt strongly appropriate for multi-decisional team meetings. In particular, being the collaboration between specialists the cornerstone of cancer treatment, telemedicine can contribute overcoming some barriers that often limit its effectiveness (e.g., increased productivity, remote reporting, and reduced travel costs).

Interestingly, agreement was not reached regarding the cost of a teleconsultation compared to an in-person assessment. In this context, none of the proposed statements were deemed appropriate. The lack of long-standing experience in telehealth care among the panelists may partly explain this finding.

Our study has some limitations. The exact role of telemedicine in colorectal practice remains to be established. However, the agreed goal was to lay the foundation for understanding and preventing harm caused by its reckless use. Despite being selected upon their publication track record in the colorectal field, participants’ overall experience with telemedicine was scarce at the time of consensus. Hence, judgments may have reflected a more skeptical view concerning the applicability of telemedicine to a specialty where objective examination is sacrosanct. The good balance of older and younger generations among panelists could have helped to mitigate the selection bias at the cost of low levels of agreement.

Conclusion

The tragedy of the pandemic has prompted our recognition and understanding of telemedicine’s importance. This e-consensus may support healthcare stakeholders in planning structural interventions for the future. It is advisable that all tertiary colorectal centers should have a teleconsultation system. Standardization of infrastructures and costs remain to be better elucidated.

Change history

21 September 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-01157-6

References

Gallo G, La Torre M, Pietroletti R, Bianco F, Altomare DF, Pucciarelli S, Gagliardi G, Perinotti R (2020) Italian society of colorectal surgery recommendations for good clinical practice in colorectal surgery during the novel coronavirus pandemic. Tech Coloproctol 24(6):501–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02209-6

Santoro GA, Grossi U, Murad-Regadas S, Nunoo-Mensah JW, Mellgren A, Di Tanna GL, Gallo G, Tsang C, Wexner SD, D-C Group (2021) Delayed colorectal cancer care during COVID-19 pandemic (DECOR-19): global perspective from an international survey. Surgery 169(4):796–807

Sturiale A, Pata F, De Simone V, Pellino G, Campenni P, Moggia E, Manigrasso M, Milone M, Rizzo G, Morganti R, Martellucci J, Gallo G (2020) Internet and social media use among patients with colorectal diseases (ISMAEL): a nationwide survey. Colorectal Dis 22(11):1724–1733

Tyler KM, Baucom R (2020) What every colorectal surgeon should know about telemedicine. Dis Colon Rectum 63(4):418–419

Gallo G, Grossi U, Sturiale A, Di Tanna GL, Picciariello A, Pillon S, Mascagni D, Altomare DF, Naldini G, Perinotti R (2021) Telemedicine in Proctology Italian Working, E-consensus on telemedicine in proctology: a RAND/UCLA-modified study. Surg 170(2):405–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2021.01.049

Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR, Lazaro P, van het Loo M, McDonnell J, Vader J, Kahan JP (2001) The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user's manual. RAND Corporation

Knowles CH, Grossi U, Horrocks EJ, Pares D, Vollebregt PF, Chapman M, Brown SR, Mercer-Jones M, Williams AB, Hooper RJ, Stevens N, Mason J, N.C.w. Group (2017) Pelvic floor, surgery for constipation: systematic review and clinical guidance: paper 1: introduction & methods. Colorectal Dis 19 (Suppl 3):5–16

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

Watson AR (2021) Why surgeons must adopt and leverage telemedicine: this journey is part of our DNA. Surgery 169(2):225–226

Wee D, Li X, Suchman K, Trindade AJ (2021) Patient centered outcomes regarding telemedicine prior to endoscopy during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tige.2021.03.003

Augestad KM, Sneve AM, Lindsetmo RO (2020) Telemedicine in postoperative follow-up of STOMa PAtients: a randomized clinical trial (the STOMPA trial). Br J Surg 107(5):509–518

Wehrle CJ, Lee SW, Devarakonda AK, Arora TK (2021) Patient and physician attitudes toward telemedicine in cancer clinics following the COVID-19 pandemic. JCO Clin Cancer Inf 5:394–400

Ruf B, Jenkinson P, Armour D, Fraser M, Watson AJ (2020) Videoconference clinics improve efficiency of inflammatory bowel disease care in a remote and rural setting. J Telemed Telecare 26(9):545–551

Sellars H, Ramsay G, Sunny A, Gunner CK, Oliphant R, Watson AJM (2020) Video consultation for new colorectal patients. Colorectal Dis 22(9):1015–1021

Sidpra J, Chhabda S, Gaier C, Alwis A, Kumar N, Mankad K (2020) Virtual multidisciplinary team meetings in the age of COVID-19: an effective and pragmatic alternative. Quant Imaging Med Surg 10(6):1204–1207

Aghdam MRF, Vodovnik A, Hameed RA (2019) Role of telemedicine in multidisciplinary team meetings. J Pathol Inform 10:35

Cathcart P, Smith S, Clayton G (2021) Strengths and limitations of video-conference multidisciplinary management of breast disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg 108(1):e20–e21

Acknowledgements

Telemedicine in Colorectal Surgery Italian Working Group: Domenico Aiello (Ospedale San Paolo, Savona, Italia), Andrea Avanzolini (General and Oncologic Surgery, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, Forlì, Italy), Francesco Balestra (General Surgery—Nuoro Hospital—ATS ASSL Nuoro), Francesco Bianco (General Surgery Unit, San Leonardo Hospital, Castellammare di Stabia, ASL NA3 Sud, Italy), Gian Andrea Binda (General Surgery, Biomedical Institute, Genoa, Italy), Gabriele Bislenghi (Department of Abdominal Surgery, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium), Andrea Bondurri (Department of General Surgery, Luigi Sacco University Hospital, ASST FBF-Sacco, Milan, Italy), Salvatore Bracchitta (Mediterraneo Clinic, Ragusa, Italy), Alberto Buonanno (Chirurgia Generale, ASUR Marche Area Vasta n. 5, Ospedale Madonna del Soccorso, San Benedetto del Tronto, Italy), Filippo Caminati (SOSD Proctologia USL Toscana Centro, Prato, Italy), Valerio Celentano (Colorectal Unit, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK), Claudio Coco (U.O.C. Chirurgia Generale 2, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario "Agostino Gemelli" IRCCS, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy), Francesco Colombo (L. Sacco University Hospital, Milan, Italy), Paola De Nardi (Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy), Francesca Di Candido (Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center IRCCS, Milan, Italy), Salomone Di Saverio (Surgery I Unit, University Hospital of Varese, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy), Francesco Ferrara (Department of Surgery, San Carlo Borromeo Hospital, ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Milan, Italy), Cristina Folliero (General Surgery Unit, Santa Maria della Misericordia Hospital, Udine, Italy), Iacopo Giani (SOSD Proctologia USL Toscana Centro, Prato, Italy), Maria Carmela Giuffrida (Department of Surgery, General and Oncologic Surgery Unit, Santa Croce e Carle Hospital, Cuneo, Italy), Aldo Infantino (Surgical Unit, Department of General Surgery, Santa Maria dei Battuti Hospital, San Vito al Tagliamento, Italy), Marco La Torre (Coloproctology Unit, Salvator Mundi International Hospital, UPMC University of Pittsburgh Medical Center), Giorgio Lisi (Department of Surgery, Sant' Eugenio Hospital, Rome, Italy), Gaetano Luglio (Surgery, Department of Public Health, School of Medicine Federico II of Naples, Naples, Italy), Anna Maffioli (General Surgery Department, ASST Fatebenefratelli-Sacco, Luigi Sacco University Hospital, Milan, Italy), Stefano Mancini (Department of General Surgery Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy), Michele Manigrasso (Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, "Federico II" University of Naples, Naples, Italy), Fabio Marino (Surgery Unit, National Institute of Gastroenterology "S. de Bellis", Research Hospital, Castellana Grotte, Italy), Jacopo Martellucci (General, Emergency and Mini-Invasive Surgery, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy), Giovanni Milito (General Surgery Unit, Valle Giulia Clinic, Rome, Italy), Marco Milone (Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, "Federico II" University of Naples, Naples, Italy), Simone Orlandi (Intestinal Diseases Centre, Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar, Verona, Italy), Massimo Ottonello (Chirurgia Generale, ASL3 Genovese, Genova, Italy), Francesco Pata (General Surgery Unit, Nicola Giannettasio Hospital, Corigliano-Rossano, Italy), Gianluca Pellino (Department of Advanced Medical and Surgical Sciences, Università degli Studi della Campania 'Luigi Vanvitelli', Naples, Italy), Roberto Perinotti (Colorectal Surgical Unit, Department of Surgery, Infermi Hospital, Biella, Italy), Beatrice Pessia (Department of Surgery, University of L'Aquila, L'Aquila, Italy), Arcangelo Picciariello (University “Aldo Moro” of Bari, Bari, Italy), Aldo Rocca (Department of Medicine and Health Sciences “V. Tiberio”, University of Molise, Campobasso), Lucia Romano (San Salvatore Hospital. Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L'Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy), Giulio Santoro (4th Surgery Unit, Regional Hospital Treviso, DISCOG, University of Padua, Padua, Italy), Alberto Serventi (Department of Surgery, Monsignor Galliano Hospital, Acqui Terme, Italy), Giuseppe Sigismondo Sica (Department of Surgical Science, University Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy), Rocco Spagnuolo (Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, "Magna Graecia" University, Catanzaro, Italy), Antonino Spinelli (Department of Biomedical Sciences, Humanitas University, Pieve Emanuele—Milan, Italy; IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano—Milan, Italy), Alessandro Testa (Surgery Department, San Pietro–Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Rome, Italy), Mario Trompetto (Department of Colorectal Surgery, S. Rita Clinic, Vercelli, Italy), Roberta Tutino (Department of Surgical, Oncological and Stomatological Disciplines, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy), Antonella Veglia (General Surgery Unit, P.O. Cardarelli, Campobasso, Molise, Italy), Gloria Zaffaroni (Department of General Surgery, L. Sacco Hospital, Milano, Italy).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Telemedicine in Colorectal Surgery Italian Working Group author names are listed in Acknowledgements.

The original article has been updated: Due to collaborators update.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallo, G., Picciariello, A., Di Tanna, G.L. et al. E-consensus on telemedicine in colorectal surgery: a RAND/UCLA-modified study. Updates Surg 74, 163–170 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-01139-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-01139-8