Abstract

Introduction

In this analysis, we aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of discontinuing aspirin (ASA) after short-term use versus its continuous use with a P2Y12 inhibitor for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods

From May to June 2020, electronic databases were searched for related publications. The cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes representing efficacy and safety, respectively, were the endpoints of this study. The new RevMan software version 5.4 was used to analyze the data. Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to represent the results following data analysis.

Results

A total of 9774 participants with T2DM were included in this analysis, whereby 4941 patients were assigned to the ASA discontinuation group and 4833 patients to the dual antiplatelet (DAPT) group. Our result showed that compared to a longer duration (12 months) of DAPT (ASA + P2Y12 inhibitor) use in these patients with T2DM, discontinuing ASA after short-term use (1–3 months) thereafter using only a P2Y12 inhibitor (mono-therapy) was not associated with a significant increase in the risk of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.76–1.12; P = 0.39), myocardial infarction (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.75–1.26; P = 0.86), all-cause mortality (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.60–1.02; P = 0.07), cardiac death (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.43–1.35; P = 0.35), stroke (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.67–1.67; P = 0.80) and stent thrombosis (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.58–1.65; P = 0.93). However, discontinuing ASA after short-term use in these patients with T2DM was associated with a lower risk of bleeding defined according to the Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2–5 (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.73; P = 0.0001), and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) defined as major (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.75; P = 0.0001) and minor bleeding (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43–0.78; P = 0.0004).

Conclusion

Discontinuing ASA after short-term use for the treatment of patients with T2DM following PCI was not associated with any increased cardiovascular outcomes. Also, discontinuing ASA after short-term use and continuing the use of a P2Y12 inhibitor were somewhat safer in these patients with T2DM. Further research should follow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular diseases are two major non-communicable diseases affecting a large population worldwide. |

In patients with ACS, revascularization by either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been the treatment strategy. |

Following revascularization of the coronary vessels, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin (ASA) and a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) is prescribed. |

The efficacy and safety of discontinuing ASA is not known. |

What was learned from this study? |

Discontinuing ASA after short-term use and continuing the use of a P2Y12 inhibitor is equally effective and somewhat safer in patients with T2DM. |

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular diseases are two major non-communicable diseases affecting a large population worldwide [1]. In fact, cardiovascular diseases have often been a major macro-vascular complication of T2DM [2]. Vascular disorders of the cardiac system often lead to acute coronary syndrome (ACS). In patients with ACS, revascularization by either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been the treatment strategy [3]. Following revascularization of the coronary vessels, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin (ASA) and a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel, an irreversible P2Y12 inhibitor, or ticagrelor, a direct-acting reversible oral antagonist of P2Y12) is prescribed for a duration of 6–12 months to prevent stent thrombosis or re-infarction [4]. In this analysis, we aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of discontinuing ASA after short-term use versus its continuous use with a P2Y12 inhibitor for the treatment of patients with T2DM following PCI.

Methods

Search Databases

From May to June 2020, the databases of Cochrane Library, EMBASE database, MEDLINE database, http://ClinicalTrials.gov, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar were searched for publications showing ASA discontinuation after short-term use versus its continuous use with a P2Y12 inhibitor for the treatment of patients following PCI.

Search Strategies

This search was carried out using the following terms or phrases:

-

Short-term aspirin and percutaneous coronary intervention;

-

Discontinuation of aspirin and percutaneous coronary intervention;

-

Short-term aspirin, diabetes mellitus and percutaneous coronary intervention;

-

Discontinuation of aspirin, diabetes mellitus and percutaneous coronary intervention;

-

Short-term dual antiplatelet therapy and percutaneous coronary intervention;

-

Short-term dual antiplatelet therapy, diabetes mellitus and percutaneous coronary intervention;

Abbreviations such as PCI, ASA, DAPT and T2DM were also used.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Trials were included if:

-

(1)

They compared cardiovascular outcomes in patients who discontinued ASA after short-term use versus its continuous use along with a P2Y12 inhibitor after PCI;

-

(2)

They consisted of participants with T2DM.

Trials were excluded if:

-

(1)

They did not involve participants with T2DM;

-

(2)

They did not report cardiovascular outcomes;

-

(3)

They were not based on discontinuing ASA;

-

(4)

They were duplicated studies;

-

(5)

They were published in a different language than English.

Outcomes and Definitions of Terms

The outcomes that were assessed in the original trials are listed in Table 1. Based on this list of outcomes, the endpoints selected for this analysis included:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) (consisting of death, myocardial infarction and stroke);

-

Myocardial infarction (MI);

-

All-cause mortality;

-

Cardiac death;

-

Stroke;

-

Stent thrombosis;

-

Bleeding defined by the Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2–5 [5];

-

Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) defined minor and major bleeding [6].

Four trials reported a 12-month follow-up time period, whereas one trial had a 24-month follow-up time period.

The types of antiplatelet drugs that were used included aspirin and either ticagrelor or clopidogrel. Aspirin was discontinued after 3 months, and a P2Y12 inhibitor was continued for up to 12 months in three studies, whereas aspirin was discontinued after 1 month in two other studies.

In the experimental (study) group, ASA was discontinued and only a P2Y12 inhibitor was continually used for at least 12 months, whereas in the control group, ASA was continually used with a P2Y12 inhibitor (DAPT) for the whole 12 months.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data were independently extracted by the authors. The authors carefully assessed all the selected publications, and data related to the total number of T2DM participants assigned to the discontinuation of ASA and the continuation of ASA with P2Y12 inhibitor groups, respectively, were extracted. Duration of ASA or DAPT use and the follow-up time periods were all extracted. The respective outcomes and the number of events associated with each outcome were also extracted. In addition, the baseline characteristics, which involved mainly comorbidities or risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and being a current smoker within the T2DM participants, as well as the methodologic features of the original studies, were also noted down.

Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and a diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg on at least two separate occasions.

Dyslipidemia was defined as an elevation of lipid levels (triglyceride/cholesterol) in the blood.

Current smokers were defined as participants who were smoking during the time period when the study was being conducted.

The methodologic quality of the trials were assessed by the recommendations suggested by the Cochrane collaborations [7] (score grade A to C).

If any of the authors experienced any difficulty during the data extraction process or disagreed with the inclusion of certain data, disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Statistical Analysis

The most recent version of RevMan (5.4) was used for the systematic analysis. Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to represent the results following data assessment. Two simple methods were used to assess heterogeneity: (1) the Q statistic test whereby a P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant and (2) the I2 statistic test whereby heterogeneity was considered to increase with an increasing I2 value. For subgroup analyses with low heterogeneity, a fixed statistical model was used; otherwise, a random statistical model was used.

Sensitivity analysis was also carried out. In addition, publication bias was visually observed through assessment of the funnel plot.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Searched Outcomes

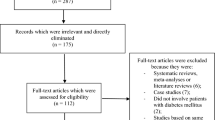

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline was followed [8]. Three hundred five publications were obtained. Based on a careful assessment of the titles and abstracts, 269 irrelevant publications were eliminated. Thirty-six full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Among the full-text articles, 3 non-randomized trials, 2 case studies, 1 meta-analysis, 1 post hoc analysis and 24 repeated studies were eliminated. Finally, only five trials [9,10,11,12,13] were included in this analysis, as shown in Fig. 1.

Main Characteristics of the Studies

A total of 9774 participants with T2DM were included in this analysis, whereby 4941 patients were assigned to the ASA discontinuation group and 4833 were assigned to the DAPT group, as shown in Table 2. All the studies were randomized trials in which participants were enrolled between the years 2013–2018.

Baseline Features

Table 3 lists the baseline features. Mean age of the participants varied from 61.0 to 69.1 years. The majority of the participants were males (72.7–80.0%). Patients suffering from hypertension (50.0–74.0%), dyslipidemia (45.1–74.8%) and current smokers (20.4–38.0%) are also listed in Table 3.

Results of this Analysis

Our result showed that compared to a longer duration of DAPT (ASA + P2Y12 inhibitor) use in these patients with T2DM, discontinuing ASA after short-term use thereafter using only a P2Y12 inhibitor (mono-therapy) was not associated with a significant increase in the risk of MACCE (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.76–1.12; P = 0.39), MI (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.75–1.26; P = 0.86), all-cause mortality (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.60–1.02; P = 0.07), cardiac death (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.43–1.35; P = 0.35), stroke (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.67–1.67; P = 0.80) and stent thrombosis (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.58–1.65; P = 0.93) as shown in Fig. 2.

In fact, discontinuing ASA after short-term use in these patients with T2DM was associated with a lower risk of BARC defined bleeding type 2–5 (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.73; P = 0.0001), TIMI defined major bleeding (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.75; P = 0.0001) and TIMI defined minor bleeding (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43–0.78; P = 0.0004) as shown in Fig. 3.

The results are summarized in Table 4.

Consistent results were obtained throughout during the sensitivity analysis. There was no evidence of publication bias across the original studies that were involved in assessing the clinical endpoints of this analysis. This was proven through the visual assessment of the funnel plot (Fig. 4) that was generated.

Discussion

Several studies have shown most patients with T2DM have platelet dysfunction or platelet hyperactivity [14,15,16] and might require a more potent antiplatelet regimen [17]. The aim of this analysis was to compare the efficacy and safety outcomes associated with the early discontinuation of ASA after short-term use versus its continuous use with a P2Y12 inhibitor in patients with T2DM following PCI.

Our results showed that the early discontinuation of ASA following PCI was not associated with a significant increase in major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction, stroke, stent thrombosis and all-cause mortality. On the contrary, the early discontinuation of ASA was associated with a significantly lower bleeding risk.

Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 32,145 general participants with coronary artery disease showed that discontinuing ASA with continued P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy use was associated with a lower bleeding risk when the former drug was stopped 1–3 months after PCI. The authors also did not observe any significant increase in major adverse cardiac events even in those patients with ACS [18].

Moreover, a post hoc analysis of the randomized GLOBAL LEADERS trial, which is a randomized, open-labeled superiority trial comparing two antiplatelet treatment strategies after PCI and that included 130 secondary/tertiary care hospitals in different countries, the authors showed that continuing the use of ASA could be associated with higher bleeding risk and did not appear to be beneficial when used with a P2Y12 inhibitor during long-term use after PCI [19].

Limitations

This study also has limitations. First, few research articles were based on this particular topic; therefore, the total number of original studies and total number of participants with T2DM were limited. Second, P2Y12 inhibitors included either clopidogrel or ticagrelor. Using two different drugs, even if they belong to the same family, might slightly affect the results. Moreover, three studies reported discontinuation of ASA after 3 months of use following PCI, whereas two other studies reported the discontinuation of ASA only 1 month after PCI. This might affect the results of this analysis. Also, even though in all the studies P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy was used for a total of 1 year, one study reported the use of ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months after discontinuation of ASA. Another limitation was the fact that several endpoints including target vessel revascularization, target lesion revascularization and other bleeding outcomes could not be assessed since they were reported in only one study, so a comparison was not possible. In addition, the dosage of antiplatelet agents varied with studies, and this could be another limitation of this analysis. Finally, our analysis was based on the general population with T2DM. However, the impact or influence of antiplatelet therapy on the duration or degree of illness was not known.

Conclusions

Discontinuing ASA after short-term use for the treatment of patients with T2DM following PCI was not associated with increased cardiovascular outcomes. In fact, the risks of minor and major bleeding were significantly decreased with discontinuation of ASA in contrast to its continuous use with a P2Y12 inhibitor for the treatment of patients with T2DM following PCI. Hence, discontinuing ASA was somewhat safer in these patients with T2DM. Further research should follow.

References

Balakumar P, Khin M-U, Jagadeesh G. Prevalence and prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113(Pt A):600–9.

Petak S, Sardhu A. The intersection of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2018;14(4):249–50.

Spadaccio C, Benedetto U. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) vs. percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the treatment of multivessel coronary disease: quo vadis?—a review of the evidences on coronary artery disease. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018;7(4):506–15.

Chen H, Power D, Giustino G. Optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after PCI: integrating procedural complexity, bleeding risk and the acuteness of clinical presentation. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2018;16(10):735–48.

Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2736–47.

Hicks KA, Stockbridge NL, Targum SL, Temple RJ. Bleeding Academic Research Consortium consensus report: the Food and Drug Administration perspective. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2664–5.

Higgins JP, et al. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: Wiley; 2008. p. 187–241.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcareinterventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Hahn J-Y, Song YB, Oh J-H, et al. Effect of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy vs dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SMART-CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(24):2428–37.

Kim B-K, Hong S-J, Cho Y-H, et al. Effect of ticagrelor monotherapy vs ticagrelor with aspirin on major bleeding and cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the TICO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2407–16.

Mehran R, Baber U, Sharma SK, et al. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin in high-risk patients after PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2032–42.

Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Jüni P, et al. Ticagrelor plus aspirin for 1 month, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months vs aspirin plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor for 12 months, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months after implantation of a drug-eluting stent: a multicentre, open-label, randomised superiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):940–9.

Watanabe H, Domei T, Morimoto T, et al. Effect of 1-month dual antiplatelet therapy followed by clopidogrel vs 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients receiving PCI: the STOPDAPT-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(24):2414–27.

Watala C, Boncler M, Gresner P. Blood platelet abnormalities and pharmacological modulation of platelet reactivity in patients with diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57(Suppl):42–58.

Vazzana N, Ranalli P, Cuccurullo C, Davì G. Diabetes mellitus and thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2012;129(3):371–7.

Santilli F, Simeone P, Liani R, Davì G. Platelets and diabetes mellitus. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2015;120:28–39.

Patti G, Proscia C, Di Sciascio G. Antiplatelet therapy in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute coronary syndrome. Circ J. 2014;78(1):33–41.

O’Donoghue ML, Murphy SA, Sabatine MS. The safety and efficacy of aspirin discontinuation on a background of a P2Y 12 inhibitor in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.046251.

Tomaniak M, Chichareon P, Onuma Y, et al. Benefit and risks of aspirin in addition to ticagrelor in acute coronary syndromes: a post hoc analysis of the randomized GLOBAL LEADERS trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(11):1092–101.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

QW, KY and PKB were responsible for the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the initial manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. QW wrote the final draft. All the three authors approved the final manuscript as it has been written.

Disclosures

The authors Qiang Wang, Keping Yang and Pravesh Kumar Bundhun declare that they have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This meta-analysis is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. References of the original papers involving the data sources that have been used in this paper have been listed in the main text of this current manuscript. All data are publicly available in electronic databases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12793766.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Yang, K. & Bundhun, P.K. Discontinuing Aspirin After Short Term Use Versus Continuous Use with a P2Y12 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Meta-analysis. Diabetes Ther 11, 2299–2311 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00909-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00909-8