Abstract

Poisoning of wild birds following ingestion of lead from ammunition has long been recognised and considerable recent research has focused on terrestrial birds, including raptors and scavengers. This paper builds upon previous reviews and finds that both the number of taxa affected and geographical spread of cases has increased. Some lead may also be absorbed from embedded ammunition fragments in injured birds which risk sub-lethal and welfare effects. Some papers suggest inter-specific differences in sensitivity to lead, although it is difficult to disentangle these from other factors that influence effect severity. Sub-lethal effects have been found at lower blood lead concentrations than previously reported, suggesting that previous effect-level ‘thresholds’ should be abandoned or revised. Lead poisoning is estimated to kill a million wildfowl a year in Europe and cause sub-lethal poisoning in another ≥ 3 million. Modelling and correlative studies have supported the potential for population-level effects of lead poisoning in wildfowl, terrestrial birds, raptors and scavengers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lead toxicity to humans has been known for centuries, attracting considerable attention as a public health issue in the late twentieth century when longitudinal studies highlighted irreversible effects of low-level chronic exposure to lead on children’s IQ. Introduced legislation subsequently controlled or eliminated many uses of lead (e.g. in petrol and paint) to reduce exposure (Stroud 2015). Lead poisoning of wildlife from ammunition (gunshot or bullets) has been recognised for over a century (Calvert 1876). Birds suffer lead poisoning following direct ingestion (i) of spent lead gunshot from the environment or (ii) of ammunition or ammunition-fragments embedded in their food. (i) is widespread among wildfowl and terrestrial game birds, especially those with a muscular gizzard that eat grit to help grind their food; (ii) among raptors and scavenging birds that eat birds and mammals shot by people, or their discarded remains. An extensive literature links avian lead poisoning to ammunition sources. This includes experimental evidence of dose-dependent effects and field evidence of source, pathway and effects including: ammunition fragments in the alimentary tract of dead and living birds (through post-mortem and x-radiography examinations); ammunition fragments in regurgitated pellets (primarily of raptors); temporal and spatial correlations between elevated tissue lead levels in birds and hunting activities; spatial analyses of elevated tissue lead concentrations in relation to potential sources of exposure to spent ammunition and lead isotopic studies to match tissue lead concentrations with sources. Studies provide overwhelming support for ammunition-derived lead being the major contributor to elevated tissue lead concentrations in wild birds. However, while substantial progress has been made at reducing human exposure to lead from a variety of sources, progress with reducing wildlife exposure to lead from ammunition has been patchy and sometimes ineffective. Lead gunshot has been banned and replaced with non-toxic alternative ammunition types in some places or for some uses (e.g. for all wildfowl hunting in the USA from 1991/92 and all shooting in Denmark from 1996). Many reviews, workshops and conferences have considered this subject in recent decades. Of particular significance are the proceedings of: an International Waterfowl and Wetlands Research Bureau Workshop (Pain 1992); a conference in the USA convened by The Peregrine Fund addressing the implications of lead from spent ammunition for both wildlife and human health (Watson et al. 2009); a symposium held at Oxford University in the UK (Delahay and Spray 2015) and the publication of the final report of the Lead Ammunition Group (LAG 2015), set up to advise the UK government on risks from lead ammunition and mitigation options. A recent proposal for a European Union-wide restriction on the use of lead gunshot for shooting in and over wetlands also includes a detailed evidence review (ECHA 2017). Two scientific consensus reports draw attention to the overwhelming support given by environmental and public health scientists to evidence about the toxic effects on humans and wildlife of lead from ammunition and the need to prevent them (Group of Scientists 2013, 2014). In the following review we do not attempt to repeat previous reviews. Instead, we summarise their key conclusions and update them with results from the substantial literature published during the last 5 years. We evaluate whether the evidence underlying previous conclusions has been reinforced or refuted and highlight areas of research where understanding has been significantly advanced.

Methods

A literature search using ‘Web of Science’ was conducted for the period 2013–2018 using the following search terms: Lead, ammunition; lead, ammunition, poisoning; bird/reptile/amphibian/mammal/invertebrate/fish and lead and poisoning; bird/reptile/amphibian/mammal/invertebrate/fish and lead and ammunition/bullet/shot; lead, shot, poisoning; lead, bullet, poisoning; lead, game (sorted by animal and poisoning); game; wildlife, lead, poisoning; fishing, lead, poisoning; angling, lead, poisoning; wildfowl, lead, poisoning; waterfowl, lead, poisoning; blood, lead, bird; scavenger, lead, poisoning; vulture, lead, poisoning; plant, lead, ammunition. Preliminary searches of other databases were subsequently undertaken (e.g. Google Scholar and simple ‘Google’ online searches) but it soon became evident that the vast majority of relevant literature had been identified by Web of Science. References that the authors considered added to previous reviews, expanded information or contradicted the conclusions of previous reviews are included below. For brevity, material that simply confirmed the conclusions of previous reviews, or dealt with methodological issues not directly relevant to current knowledge of the effects of lead from ammunition on wildlife, generally has not been included. The literature search was initially conducted in summer 2018 and updated at the end of December 2018.

Effects of lead on wildlife

Lead is a toxic non-essential metal that has no compensatory beneficial effects in living organisms. It is an accumulative metabolic poison that is non-specific, affecting a wide range of physiological and biochemical systems including the haematopoietic, vascular, nervous, renal, immune and reproductive systems. It causes adverse effects on behaviour and survival (Eisler 1988; ATSDR 2007; EFSA 2010). After absorption by a vertebrate animal, inorganic lead effects are independent of its source. Birds are the most studied and probably the most affected taxon with respect to poisoning from the ingestion of lead from ammunition. However, the toxic effects of lead are broadly similar in all vertebrates and well known from numerous experimental and field studies (reviewed in Eisler 1988; Pattee and Pain 2003; Franson and Pain 2011). Clinical signs of poisoning in birds are often associated with chronic extended exposure at a level that is not initially likely to cause immediate failure of biological function or death, although death may result. Signs include anaemia, lethargy, muscle wastage and loss of fat reserves, green diarrhoea staining the vent, wing droop, loss of balance and coordination and other neurological signs such as leg paralysis or convulsions (e.g. Wobester 1997; Friend and Franson 1999; Pattee and Pain 2003). In contrast, after acute exposure to high levels of lead, birds die rapidly without such signs.

After ingestion of ammunition or ammunition fragments by birds, lead may be eliminated rapidly from the alimentary tract with little lead absorption, retained until completely eroded, solubilised and absorbed, or show any intermediate outcome. Absorbed lead is transported in the bloodstream and deposited rapidly into soft tissues, primarily the liver and kidney, but also into bone and the growing feathers of birds. Lead in bone is retained for long periods and accumulates during an animal’s lifetime, whereas lead in soft tissues has a much shorter half-life (weeks to months). Blood lead (PbB) remains elevated for weeks or months after exposure. Previously suggested ‘thresholds’ to guide the interpretation of tissue lead concentrations are given in Table 1. The physiological effects of lead in birds have been widely reviewed (e.g. Pain and Green 2015). An individual bird’s susceptibility to lead poisoning is influenced by many biological and environmental factors and the sensitivity to lead seems, to some degree, to vary between species. In addition to the direct impacts of lead on welfare and survival, indirect effects are likely to occur. These may include increased susceptibility to infectious diseases, parasite infestations (via lead’s immunosuppressive effects), and increased susceptibility to death from a range of other causes, such as collision with power lines (Kelly and Kelly (2005), Ecke et al. (2017)—via its effects on muscular strength and coordination) and being shot (e.g. shown by Bellrose 1959; reviewed in Pain and Green 2015).

It is currently considered that there are no identified “no observed adverse effect levels” (NOAEL) or “predicted no effect concentrations” (PNEC) for lead in humans (EFSA 2010) and the same is thus likely for other vertebrates. Hence, the use of acceptable thresholds for exposure to lead involves acceptance of some level of avoidable harm.

Pathways of exposure

Movement of lead derived from spent ammunition into animals via water, soil and plants

The deposition of lead ammunition into the environment can result in elevated soil and water concentrations in relation to the amount deposited and environmental conditions. Wild animals can be exposed to ammunition-derived lead from water or the ingestion of contaminated soil, or via plants or lower organisms that have taken up such lead (reviewed in LAG 2015; Pain and Green 2015). Comparatively little information exists on wildlife effects via these pathways relative to the direct ingestion of lead ammunition or fragments. Recent studies on non-avian taxa support uptake of and effects of ammunition-derived lead via these pathways. One recent study (Rodríguez-Seijo et al. 2017) found high lead levels in soils and the whole bodies of the lumbricid worm Eisenia andrei associated with an abandoned shooting range in northwest Spain. High contents of lead and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) in soil samples and in E. andrei, were associated with a reduction in the number of juveniles produced [although this was from both PAH and Pb combined], whereas, Vibrio fischeri, Raphidocelis subcapitata and Daphnia magna displayed a slight toxic response to the soil leachates tested.

Mariussen et al. (2017) studied the accumulation of lead (Pb) in brown trout (Salmo trutta) from Lake Kyrtjønn within an abandoned shooting range in Norway, compared to a nearby reference site (both lakes were acidic). Brown trout from Lake Kyrtjønn had significantly elevated lead in bone and other tissues and significantly inhibited ALAD activity in the blood compared to those from the reference site. Trout eggs were placed in stream outlets from both lakes and lead concentrations were significantly elevated in eggs and alevins from Lake Kyrtjønn compare to the reference lake. The authors concluded that adult brown trout, fertilised eggs and alevins, may be subjected to increased stress due to chronic exposure to Pb.

Direct ingestion of spent lead ammunition from the environment

Lead gunshot has been used for centuries. An estimated 600–700 million cartridges containing lead gunshot (18 000–21 000 tonnes of lead; c. 200 thousand million individual gunshot) are used annually in Europe for hunting. Some of it instantly kills the animals at which it is fired, but a proportion of them are wounded. The viscera of killed animals of some species, such as deer, are discarded in the environment. Only a small proportion of gunshot strike their targets, and so the remaining spent ammunition is dispersed widely into the environment (ECHA 2017). Under most environmental conditions, metallic lead is relatively stable. Over time, ammunition lead deposited on the soil or in water will degrade through a process of erosion and chemical reaction and lead compounds with different solubilities may form on its surface. Soil lead concentrations generally increase, especially in areas of high deposition and/or when soil conditions, such as low pH, facilitate this. Degradation of lead shot is slow, probably taking tens to hundreds of years. Thus a “historical legacy” of gunshot remains available to wildlife, increasing over time where shooting with lead gunshot continues. Gunshot generally sinks slowly through most types of soil and mud and may be available to feeding birds for many years, although a high proportion of gunshot ingested is that most recently deposited. Pain et al. (2015) review this in relation to soil types and management practices.

Gunshot densities are higher in areas of intense or regular shooting. In wetlands, densities may range from just a few to several hundred gunshot/m2 (Fig. 1) but thousands/m2 can be found in some situations like target shooting areas (e.g. O’Halloran et al. 1988).

Densities of lead shot in wetlands due to waterfowl hunting and sport shooting. Modified from Descalzo and Mateo (2018), updated from Mateo (2009). Shot densities are from individual or multiple sites in each country and from depths ranging from 5 to 30 cm. Data from Table 2 of Descalzo and Mateo (2018), updated from Mateo (2009)

There is evidence of direct ingestion of spent ammunition from soil or mud by many species of birds including wildfowl, some other water birds and game birds across Europe, North America and other countries where studies have been conducted. A substantial body of evidence spanning more than half a century exists documenting this pathway (e.g. Mateo 2009; Pain and Green 2015). Reported levels of gunshot ingestion, in terms of the proportions of killed or trapped birds with shot in the alimentary tract vary among wildfowl species according to their feeding habits. Species that feed on seeds and hard-bodied benthic animals, such as molluscs, tend to ingest larger particles of grit to assist in breaking up their food, whereas species that graze plant leaves ingest small grit particles. For a given wildfowl species, or for species with comparable feeding ecology, the proportion of birds with ingested shot tends to be higher in Europe than North America (Fig. 2). Few recent papers add to the literature on this pathway, presumably because the literature is already vast and few questions remain unanswered. Also, legislation has been introduced in some places to limit exposure—although this is incomplete and has met with variable success (see papers is Delahay and Spray 2015). The few recent studies on this pathway support previous conclusions of exposure where a pathway exists, and further document the wide geographical extent of the problem and range of species affected.

Prevalence of Pb shot ingestion in waterfowl species from North America (n = 171 697) and Europe (n = 75 761). Modified from Mateo (2009). American wigeon (Anas americana), Eurasian wigeon (Anas penelope), gadwall (Anas strepera), green-winged teal (Anas carolinensis), common teal (Anas crecca), mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), northern pintail (Anas acuta), northern shoveler (Anas clypeata), common pochard (Aythya ferina), redhead (Aythya americana)

Recent European studies have reported little or no evidence of gunshot ingestion in geese feeding in areas with no hunting or low gunshot densities (Aloupi et al. 2015; Mateo et al. 2016 for studies in Greece and Bulgaria respectively). Runia and Solem (2016) found levels of lead gunshot ingestion to be about five times higher in 660 ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) harvested on shooting preserves in South Dakota USA then in 1301 birds from non-preserve areas where lead gunshot availability was presumably lower (3.9%, 95% CI 2.7–5.7% vs 0.8%, 95% CI 0.4–1.4% respectively).

Mateo et al. (2013) reviewed lead poisoning studies from Spain and reported that high densities of lead gunshot in various internationally important wetlands for waterfowl resulted in proportions of birds with ingested gunshot close to 70% in some species, such as pintail (Anas acuta). This study found that lead poisoning is a major cause of mortality of the white-headed duck (Oxyura leucocephala), listed as Endangered in the IUCN Red List. High proportions of birds with ingested gunshot (9.3% of 461 birds) were reported in chukars (Alectoris chukar) harvested in north-western Utah, USA, and 8.3% of 121 birds analysed had elevated liver lead (Bingham et al. 2015). Few studies have previously been published from Argentina. Ferreyra et al. (2014) investigated gunshot ingestion and blood lead concentrations in 415 hunter-killed ducks and 96 live-trapped ducks of 5 species in Argentina. Overall 10.4% of ducks contained ingested gunshot. Blood lead levels were elevated in 28% of ducks and exceeded 100 µg/dl, a threshold for clinical toxicity, in 8.6% of birds. Lead poisoning has been reported in the globally Vulnerable nene (Branta sandvicensis) in Hawaii (Work et al. 2015). Recent studies from Iranian wetlands found elevated levels of lead in the livers and/or kidneys of some sampled common pochard (Aythya ferina), mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), teal (Anas crecca) and gadwall (Anas strepera), with ingested gunshot suggested as a possible source (Sinkakarimi et al. 2015, 2018).

Using lead isotope analyses of blood lead levels, Binkowski et al. (2016) concluded that lead gunshot currently available in Poland was unlikely to be the source of blood lead (mean of 0.241 ppm—24 µg/dl) in mute swans (Cygnus olor) wintering in northern Poland, although these authors did not examine how the relationship between blood and ammunition isotope ratios changes with blood lead concentration, and 204Pb, upon which this conclusion relies, is not readily analysed using Q-ICP-MS (Ellam 2010).

Ingestion of lead from ammunition by raptors and scavengers

Lead from ammunition is available to predators and scavengers in the flesh of their prey either as whole gunshot/bullets or ammunition fragments. Exposure occurs when shot animals are killed but not retrieved, when parts of the carcass (e.g. offal) are discarded, or when animals are wounded but survive (and may be more vulnerable to early death later or to predation). Large numbers of some quarry species can survive carrying lead gunshot, commonly 20–30% in some wildfowl populations (Table I, Pain et al. 2015). Recent studies investigating the presence of lead fragments and/or elevated tissue lead concentrations add to evidence of the contamination of both small and large game species with lead ammunition (Warner et al. 2014; Cruz-Martinez et al. 2015; Andreotti et al. 2016; Ertl et al. 2016; Herring et al. 2016). Using wild and captive birds (ravens (Corvus corax), white-tailed eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) and common buzzards (Buteo buteo)) Nadjafzadeh et al. (2015) found that birds more frequently ingested smaller metal fragments. However, they only avoided those > 8.8 mm, which is considerably larger than most gunshot or bullet fragments. Analyses of ‘trash’ items from the nest area of California condors (Gymnogyps californianus) (Finkelstein et al. 2015) and a literature review (Golden et al. 2016) confirmed the view that, while different sources of lead are available in the landscape, most lead poisoning of scavenging birds appears to result from lead-based ammunition ingested in their food. Low tissue lead levels (liver lead < 2.1 ppm dw; N = 11) have been reported in the lesser-spotted eagle (Clanga pomarina brehm), a species that breeds in Europe but migrates to Africa, thus avoiding the European hunting season (Kitowski et al. 2017c). In contrast, a greater-spotted eagle (Clanga clanga), a related species that is associated with wetlands and susceptible to lead poisoning as it feeds on unretrieved quarry (BirdLife International 2018), was found wintering in the Ebro Delta, Spain, with an elevated blood lead level of 33.6 µg/dl (Mateo et al. 2001).

Previously, most studies documenting this exposure pathway were of condors and eagles (particularly California condor, bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) in North America, white-tailed eagle in Europe and Japan and Steller’s sea eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus) in Japan). However, many other species have been reported as exposed to and/or poisoned by lead ammunition. While fewer studies had been conducted on other species, recent research has documented exposure via this pathway in new species, taxa and locations, considerably strengthening the evidence-base and highlighting the significance of this exposure pathway. These studies are summarised in Table 2, to which previous studies, reviewed in Pain et al. (2009) add at least another 14 species.

New studies highlight the potential for exposure of mammalian scavengers and predators to ammunition lead. Legagneux et al. (2014) used camera traps to identify species scavenging on moose (Alces alces) viscera left by hunters in eastern Quebec, Canada and these included black bears (Ursus americanus). In a study of brain metal concentrations in 9 mammal species from north-western Poland, Kalisinska et al. (2016) found that raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) from an area where hunting is prohibited had a lower brain lead compared to those from hunting grounds, and speculated that the elevated levels could have resulted from ingesting lead from animals shot by hunters. Two captive cheetahs that had routinely been fed on hunted antelope or game birds were suspected to have died from lead poisoning; they had ingested bullets in their stomachs, elevated tissue lead levels and associated clinical sign of poisoning (North et al. 2015). Hivert et al. (2018) found significantly higher blood lead concentrations in captive than wild Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii). Captive Tasmanian devils were fed the meat of wild animals shot with lead ammunition. Subsequent removal from the Tasmanian devil’s diet of the lead-containing heads and wounds from shot animals resulted in a significant decrease in blood lead concentrations in animals at one of the captive study sites. These studies suggest that mammalian predators and scavengers that eat game species may also be at risk.

Movement of lead from embedded ammunition into body tissues

It is well established that lead from ammunition that has been shot into and become embedded in human body tissues can be mobilised and give rise to health effects (Weiss et al. 2017). Until recently, little was known about this possible pathway of exposure in wildlife. One study found that 2 white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) with retained lead ammunition from previous gunshot wounds had muscle tissue lead concentrations similar to controls although one had elevated bone lead levels (Zimmer and Osier 2018). Other recent work on birds suggests that some embedded lead may be mobilised. Berny et al. (2017) found that birds of prey in French wildlife centres that had embedded lead projectiles had significantly higher blood lead concentrations than those without (22.4 vs 14.3 µg/dl), suggesting that embedded lead projectiles may release lead and have long-term health effects. In Peru, 6 of 9 Andean condors (Vultur grypphus) at a rehabilitation centre had detectable blood lead levels (3.7 µg/dl to 17.4 µg/dl), with a mean of 9.95 µg/dl. The highest value was from a condor admitted due to a gunshot wound and found on radiographic examination to be carrying 45 lead pellets embedded in body tissues as confirmed by X-ray examination (L. Schaefer pers. com. cited in Wiemeyer et al. 2017). In a study of wild California condors, Finkelstein et al. (2014) found one bird that had been shot and retained embedded birdshot (small sized gunshot) in its tissues. The blood lead level was 16.6 µg/dl and the isotope ratios of birdshot and blood lead were indistinguishable. The following year the same bird was captured with clinical lead poisoning (blood lead levels 556 µg/dl) and radiography showed that it had ingested a buckshot (large sized gunshot), and still retained embedded birdshot from the previous shooting incident. The blood and buckshot lead isotope ratios were indistinguishable at this time, but the buckshot isotope ratio was measurably different from that of the birdshot. This illustrates that ingested shot presents a far greater risk to this species than embedded shot, but nonetheless that some transference of lead from embedded shot appears to occur. Similarly LaDouceur et al. (2015) measured tissue lead concentrations in 14 individual wildlife cases with embedded lead projectiles that were unrelated to the cause of death. Clinically significant liver lead concentrations were only found in two cases suggesting that embedded lead carries a relatively low risk for lead poisoning.

While the number of studies on this pathway remains small, collectively, they suggest that some of the lead from embedded gunshot may be mobilised, resulting in increased blood lead concentrations, with potential long-term effects. It currently appears that absorption of lead from embedded ammunition is likely to be modest compared with that following the ingestion of lead from ammunition, and that effects may be sub-lethal. Several authors have previously reported associations between embedded gunshot and reduced body condition or survival in birds (Madsen and Noer 1996; Tavecchia et al. 2001; Merkel et al. 2006), but it is unclear whether these effects were related to the injuries caused by shooting, sub-lethal effects of lead absorbed from embedded gunshot, a combination of these or some other explanation.

While effects from this pathway appear likely to be small in comparison to those from ingested lead, large numbers of birds could be affected because a substantial proportion of some populations of game birds survive being shot, carrying gunshot in their flesh (e.g. commonly 20–30% in some wildfowl populations—Pain et al. 2015). Should this pathway be further verified, then numbers of birds suffering welfare effects from sub-lethal poisoning would be far greater than previously supposed.

Impacts of lead poisoning on wildlife

Sub-lethal and welfare effects

Most birds that ingest lead ammunition suffer some effects as a result of absorbing above background levels of lead. These may be sub-clinical or clinical and will affect the birds’ welfare to varying degrees. In recent years considerable effort has been put into investigating the sub-lethal effects of lead from ammunition on birds, both under experimental conditions and in the wild.

Using transmission electron microscopy, Pineau et al. (2017) found marked subcellular toxicity in the liver associated with the ingestion of a single lead shot (0.177 ± 0.03 g) in experimentally dosed mallards (n = 21) compared with controls (n = 10). Experimental studies involving the dosing of pheasants (Gasparik et al. 2012; Runia and Solem 2017) and northern bobwhites (Colinus virginianus) (Tannenbaum 2012) with lead gunshot suggest that these species appear less susceptible to the acute effects of lead poisoning than others, such as mourning doves (Zenaida macroura), chukars or waterfowl. While tissue (blood and/or liver) lead concentrations of pheasants and northern bobwhites increased, and some of the biological parameters measured were negatively affected (two studies), this was to a lesser degree than in other species. Other experimental work has shown the sensitivity of certain terrestrial species to sub-lethal effects of lead, sometimes at low exposure levels. Maternal consumption of one 95-mg lead pellet affected egg size and hatchling organ development in domesticated roller pigeons (Columba livia) (Williams et al. 2017). Vallverdú-Coll et al. (2015a) reported impacts on immune response and other variables in red-legged partridges (Alectoris rufa) dosed with 1–3 lead gunshot.

Vallverdú-Coll et al. (2016a) found that female red-legged partridges dosed with three lead pellets (330 mg) had reduced egg hatching rate and males had decreased acrosome integrity and sperm motility. In contrast, when exposed to the lower dose of 1 pellet (110 mg), females produced heavier eggs and chicks and males presented increased sperm vigour. Then authors suggested that at the low exposure levels lead-induced endocrine disruption could explain the production of heavier and larger eggs by exposed females, although this effect has rarely been studied in female birds. Espín et al. (2014) investigated blood lead concentrations that cause effects on oxidative stress biomarkers using blood taken from 66 griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus) in Spain, and found that levels > 15 µg/dl can result in oxidative stress, risking damage to cell components. These and previous experimental studies suggest inter-specific variation in susceptibility to lead poisoning. Inter- and intraspecific variation in lead toxicity relates to factors that influence absorption, retention, detoxification and elimination of lead. Among these are diet (considered a key variable influencing lead absorption), age, sex, physiological condition and environmental factors such as temperature (Pattee and Pain 2003). Disentangling intrinsic variation in susceptibility from the effects of experimental conditions is complex.

Several recent studies have reported sub-lethal effects of lead in wild birds, supplementing earlier research. A histopathological study of the eyes of a bald eagle provided the first evidence of ocular lesions associated with sub-lethal but extremely elevated blood lead levels (c. 610 µg/dl—Eid et al. 2016). The prognosis for this rehabilitated bird’s vision was too poor for it to be released back to the wild. Along with other effects, body condition was negatively associated with liver lead of hunter-killed wild ducks in Argentina (Ferreyra et al. 2015) and with blood lead levels of female common eider (Somateria mollissima) in Canada (Provencher et al. 2016). Vallverdú-Coll et al. (2016b) found that in mallards from the Ebro delta (north-eastern Spain), lead exposure was associated with increased oxidative stress, affected colour expression, and impaired constitutive immunity in ways that differed between the sexes. Through analysing mineral chemistry and crystallinity, Álvarez-Lloret et al. (2014) found that lead contamination altered bone remodelling of red-legged partridges from a farmland area in Albacete, Spain, in a concentration-dependent way and that this occurred at low bone lead concentrations (< 4 ppm dw bone lead).

Several papers have reported sub-lethal effects at lower blood lead levels (PbB) than previously suggested (Table 1). This mirrors research into the effects of chronic low-level exposure in humans, with reference values for elevated PbB considered significant by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention decreasing markedly over time (CDC https://www.cdc.gov/). Vallverdú-Coll et al. (2015b) found that lead gunshot ingestion in mallards can result in maternal transfer of lead to offspring, affect their developing immune system and reduce early life stage survival. In mallard eggs from the Ebro delta (Spain) eggshell lead and duckling blood lead levels were positively correlated, and ducklings with blood levels > 18 µg/dl had reduced body mass and died during the first week post hatching. Newth et al. (2016) found elevated (> 20 µg/dl lead in blood) levels in 41.7% (125/300) of whooper swans (Cygnus cygnus). Blood lead content was significantly negatively associated with winter body condition when levels were ≥ 44 µg/dl (27/260 = 10.4%), indicating that sub-lethal impacts of lead on body condition occur at the lower end of previously recommended clinical thresholds and that a relatively high proportion of individuals in this population may be affected. Analysis of tracking data from 16 adult golden eagles trapped in northern Sweden indicated that sub-lethal blood lead concentrations reduced mean flight height and movement rate (Ecke et al. 2017). Blood lead levels of c.2.5 µg/dl appeared to reduce flight height by 10%, levels of 4.3 µg/dl by 20%, and in birds with the highest blood levels by 50%. These lead blood concentrations fall far below previously suggested thresholds (Table 1), but because of the small sample the authors suggest that further data should be collected. González et al. (2017) studied blood parameters and lead concentrations in griffon vultures submitted to Wildlife Rehabilitation Centres in Spain. 26% of birds had blood lead > 20 µg/dl. Blood lead was negatively correlated with haematocrit and digestive signs such as stasis and weight loss, though not with other clinical signs. The authors suggested that this species may be more sensitive to the toxic effects of lead than previously thought.

Deaths from lead poisoning

Few recent studies have added to the substantial body of information on deaths from lead poisoning in wildfowl with most new research on mortality covering the previously less well-studied groups of raptors and scavengers. Despite this disparity, a number of species of raptor and scavenger had previously been reported as dying of lead poisoning in Europe and North America (reviewed in Mateo 2009; Pain and Green 2015; Golden et al. 2016). As awareness of this poisoning in raptors has increased, so too has the number of research studies. Table 2 includes many recent examples of mortality from ingesting lead from ammunition (or likely from ammunition) in raptors and scavengers including Andean condor, cape vulture (Gyps coprotheres), griffon vulture, golden eagle, red kite (Milvus milvus), white-tailed eagle, bald eagle and Steller’s sea eagle and ranging geographically from Europe, the Middle East and Japan to Africa, North and South America. Many other species had already been reported as being poisoned in this way (e.g. see Pain et al. 2009).

Recent studies illustrate that some partial bans on the use of lead ammunition do little to reduce lead poisoning mortality in raptors and scavengers. In North America, lead poisoning continues to be a significant cause of mortality in bald and golden eagles, despite the ban in autumn 1991 on the use of lead ammunition for shooting waterfowl (Russell and Franson 2014; Warner et al. 2014; Yaw et al. 2017). This is largely because eagles consume lead bullet fragments in offal and carcasses left behind during big game hunting. In Japan, lead poisoning remains a problem for Steller’s sea eagles and white-tailed eagles after partial bans on the use of lead ammunition (first for shooting sika deer (Cervus nippon) and then all large game in Hokkaido in 2000, 2001 and 2004—Ishii et al. 2017). Bans on only certain types of lead ammunition (either gunshot or bullets) or only for the shooting of certain animals frequently have limited effect, and can be difficult to police (e.g. see Cromie et al. 2015 for UK example), although at one site in Spain good enforcement improved compliance (Mateo et al. 2014). In California, lead poisoning has been a major factor in both causing the extinction in the wild and then limiting the recovery of the reintroduced California condor population. After successive types of limited ban, a total ban—on the use of all lead ammunition for all hunting—will come into force in California from 2019 (Rendon Act 2013).

Numbers of birds affected

Sufficient data are available for approximate estimates to be made of annual numbers of deaths caused by lead poisoning in wildfowl. These are necessarily imprecise as many external factors affect lead-poisoning mortality from year to year, notably food availability and weather (Pattee and Pain 2003). Estimates follow the method of Bellrose (1959) and are based on proportions of birds found to have ingested different numbers of gunshot, turnover rates of gunshot in the intestine and mortality from experimental studies. Andreotti et al. (2018a) estimated that about 700 000 individuals of 16 waterbird species die annually in the European Union (EU) (6.1% of the wintering population) and one million across Europe (7.0%) as a direct effect of lead poisoning, with three times more birds suffering sub-lethal effects. This is similar to the number previously estimated by Mateo (2009). Pain et al. (2015) estimated that in the UK in the order of 50 000–100 000 wildfowl (c. 1.5–3.0% of the wintering population) die each winter (i.e. during the shooting season) as a direct result of lead poisoning (Pain et al. 2015), with several hundred thousand birds suffering sub-lethal poisoning and welfare effects. Wildfowl that die from delayed effects outside of the shooting season will be additional, as will those that ingest gunshot outside of the shooting season or die of causes exacerbated by lead poisoning (e.g. infectious diseases, collisions).

Pain et al. (2015) considered estimates of mortality for terrestrial game birds in the UK to be less accurate and precise than those for wildfowl. However, it is suggested that some hundreds of thousands of terrestrial game birds may die from lead poisoning annually. These estimated numbers are mainly due to the large numbers of pheasants and other game birds bred and released to be killed for sport in the UK every year (about 50 million—DEFRA 2013; Larkman et al. 2015). Even if the proportion of birds with ingested shot at a given time is only a few percent, several million birds are likely to ingest gunshot in the course of a year in the UK. It is possible that some birds (e.g. pheasants) may be less sensitive to the effects of lead than other terrestrial birds or waterbirds (as described in previous sections), and this may affect estimates of the numbers dying because of lead poisoning.

Most birds that ingest lead from ammunition probably suffer some effect on their welfare. These effects are likely to be severe in birds that subsequently die of lead poisoning. As described earlier, some of the lead that is embedded in the flesh of birds that have been shot but survive may also be absorbed into the blood and result in elevated PbB, albeit to a far lesser degree than ingested lead gunshot. Should this be the case, numbers of birds suffering welfare effects may be higher than current estimates. In the EU an estimated 6 million waterfowl are shot annually (AMEC 2012). While crippling ratios (the number of birds injured to those killed) are variable (e.g. Clausen et al. 2017), numbers crippled and carrying embedded gunshot may be large and may number over a million waterfowl, along with many more terrestrial birds. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to evaluate either the severity of impacts or numbers of birds potentially affected by embedded gunshot with any certainty.

Insufficient information exists to estimate numbers of raptors impacted in Europe and elsewhere although many scavenging and predatory species are affected (Table 2; Mateo 2009; Golden et al. 2016), probably including some currently unstudied species. This is consistent with what would be predicted from the source of lead and pathway of exposure.

Effects on populations

In some countries, there has been considerable debate about effects of lead from ammunition on bird population size and trend. Absence of robust information on this topic is sometimes cited as a reason for political inaction (Truss 2016). Any additional mortality of wildlife has the potential to affect population size and trends to some extent, and is certain to do so in the absence of complete, or perfect, density dependence. If density dependence exists but is not complete, population size will be lower because of lead poisoning, but it will stabilise at this lower level if the strength of density dependence is sufficient. If density dependence is absent or weak, any additional mortality, including that caused by lead poisoning, will cause a previously stable population to decline markedly or go extinct. Only if there is perfect density dependence which operates on demographic rates within the annual cycle and after the time when lead poisoning occurs, would deaths caused by lead poisoning be completely compensated for by density-dependent enhancement of survival or breeding success. Only then would lead poisoning be expected to have no effect on population size. It is difficult to measure the strength and form of density dependence in wild populations, so it is rarely known with any precision how large the effect of additional mortality on population size will be. However, a given proportion of birds poisoned is likely to have the biggest impact on species that naturally have the lowest annual mortality and reproductive rates, such as eagles and vultures.

Perfect or complete density dependence has rarely been demonstrated and is thought to be rare in the bird species affected by lead poisoning. For example, exhaustive studies of the effects of hunting on populations of mallards in North America provide no indication that the additional mortality it causes are compensated for by density-dependent processes (Nichols et al. 2015). Therefore, it is reasonable and precautionary to take evidence of additional mortality as evidence of an effect on population size and trend. Cases of populations exposed to ammunition-derived lead in which density dependence is clearly too weak to compensate for deaths caused by lead poisoning include those of the California condor in California and in the Grand Canyon. Both of these populations would decline to extinction because of poisoning from ammunition-derived dietary lead were it not for the capture, diagnosis and veterinary treatment of affected animals (Green et al. 2008).

Another approach to the assessment of population-level effects of lead poisoning is to correlate variation in population growth rates observed among geographical regions or species with levels of exposure to lead. Green and Pain (2016) found that for the eight duck species that winter in freshwater habitats in the UK, inter-specific variation in mean annual population growth rate during the period 1990/1991 to 2013/2014 was significantly negatively correlated with two independent measures of the prevalence of ingested lead gunshot in the UK and Europe. This relationship was also found for annual growth rates in the period 1966/1967 to 2013/2014, derived from smoothed population trajectories and was insensitive to the choice of period over which the effect was investigated. Duck species with high prevalence of ingested lead were more likely to have undergone a long-term population decline. These findings support the hypothesis that ingested lead gunshot affects population trend. The authors expressed particular concern about the possible impact of ingested lead gunshot on the common pochard, a species now listed as globally threatened (Vulnerable) because of population declines (BirdLife International 2015). Previously, the prevalence of lead shot ingestion was found to be negatively correlated with population trends in 15 waterbird species across Europe, in the last decades of the twentieth century (Fig. 3).

Correlation between the prevalence of lead shot ingestion and the trend of the wintering population in Europe of 15 species of waterfowl. Modified from Mateo (2009)

Conducting a modelling study of spectacled eider (Somateria fischeri), Flint et al. (2016) suggested that populations would respond most dramatically to changes in adult female survival and that reductions in adult female survival related to lead poisoning were locally important. As most mortality from lead exposure occurs over winter, the related reduction in adult survival may be impeding recovery of local populations.

Meyer et al. (2016) used population models to create example scenarios demonstrating how mortality from lead poisoning and other poisons might affect the populations of three susceptible species: grey partridge (Perdix perdix) in continental Europe, common buzzard in Germany and red kite in Wales. Lead gunshot ingestion and poisoning at modelled levels (4–16% for lead poisoning depending on species) affected populations by reducing population size and slowing population growth. Lead gunshot alone reduced the population size of grey partridges by 10%, and reduced annual growth rate of the red kite population from 6.5% to 4%, slowing recovery. Decrease in the common buzzard mean population size by lead gunshot and poisons combined was much smaller (≤ 1%). The effects are somewhat higher if ingestion of these substances additionally causes sub-lethal reproductive impairment (which we know that lead can do—as described above). While these results are subject to uncertainty, they suggest that declining or recovering populations are most sensitive to poisoning by lead from ammunition or other poisons. These example scenarios may not be replicable to other places where exposure levels differ but they do illustrate how poisoning can hypothetically affect population levels and growth rates.

Population-level effects of lead poisoning are also supported by previous research on lead fishing weights that were responsible for widespread lead poisoning in mute swans. Following a ban on the sale and use of most lead fishing weights in England and Wales in 1987 there was a sharp reduction in most areas in the numbers of mute swans dying or sick from lead poisoning. This has been considered crucial to the subsequent increase in the species’ population (Sears and Hunt 1991; Kirby et al. 1994; Perrins et al. 2003). In a long-term study (1982–2012) lead fishing weights have recently been shown to have a population-level effect on common loons (Gavia immer) in New Hampshire, USA where their ingestion was responsible for 48.6% of adult loon deaths. The authors modelled the loon population retrospectively and estimated that mortality caused by ingestion of lead tackle reduced the population growth rate by 1.4% and the state-wide population by 43% during the years of the study (Grade et al. 2018).

The known effects of lead upon physiology, behaviour and reproduction, the widespread mortality in birds known to occur as a result of exposure to lead from ammunition, and the recent studies described here provide compelling evidence that lead from ammunition can, and sometimes does, negatively affect population levels and trends, and not only in quarry species. For this reason, it is reasonable and precautionary to take evidence of additional mortality as a result of lead poisoning as evidence of population-level effects.

Conclusions

Recent research supports and supplements more than a century of work on lead poisoning from ammunition sources in birds. The results of this work show that lead poisoning of birds is likely to occur wherever lead ammunition is used and a pathway of exposure exists. Cases of lead poisoning in new species and countries simply reflect that these had not previously been studied. Taxa beyond birds are also affected; recent research highlights risks to mammalian scavengers and predators although this has not been extensively investigated. Trends in lead poisoning research in birds reflect those in human medicine, with effects detected at ever lower levels of lead exposure and absorption. Large numbers of wild birds suffer welfare effects and are killed by spent lead ammunition annually, and it affects populations. Alternative non-toxic ammunition exists and some has been in widespread use for decades. Removing this avoidable source of environmental contamination and suffering and mortality of wildlife is a matter of political will (e.g. Arnemo et al. 2016; Kanstrup et al. 2018).

References

Aloupi, M., S. Kazantzidis, T. Akriotis, E. Bantikou, and V.O. Hatzidaki. 2015. Lesser white-fronted (Anser erythropus) and greater white-fronted (A. albifrons) geese wintering in Greek wetlands are not threatened by Pb through shot ingestion. Science of the Total Environment 527: 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.04.083.

Álvarez-Lloret, P., A.B. Rodríguez-Navarro, C.S. Romanek, P. Ferrandis, M. Martínez-Haro, and R. Mateo. 2014. Effects of lead shot ingestion on bone mineralization in a population of red-legged partridge (Alectoris rufa). Science of the Total Environment 466: 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.06.103.

AMEC Environment and Infrastructure UK Limited. 2012. European Chemicals Agency. Abatement Costs of Certain Hazardous Chemicals. Lead in shot: Final Report December 2012. Report for European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). Contract No: ECHA 2011/140, Annankatu 18, 00121 Helsinki, Finland.

Andreotti, A., F. Borghesi, and A. Aradis. 2016. Lead ammunition residues in the meat of hunted woodcock: A potential health risk to consumers. Italian Journal of Animal Science 15: 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1828051X.2016.1142360.

Andreotti, A., I. Fabbri, S. Menotta, F. Borghesi, and S. Menotta. 2018a. Lead gunshot ingestion by a Peregrine Falcon. Ardeola-International Journal of Ornithology 65: 53–58.

Andreotti, A., V. Guberti, R. Nardelli, S. Pirrello, L. Serra, S. Volponi, and R.E. Green. 2018b. Economic assessment of wild bird mortality induced by the use of lead gunshot in European wetlands. Science of the Total Environment 610: 1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.085.

Arnemo, J.M., O. Andersen, S. Stokke, V.G. Thomas, O. Krone, D.J. Pain, and R. Mateo. 2016. Health and environmental risks from lead-based ammunition: Science versus socio-politics. EcoHealth 13: 618–622.

ATSDR. 2007. Toxicological profile for lead. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Atlanta Georgia USA. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf.

Behmke, S., J. Fallon, A.E. Duerr, A. Lehner, J. Buchweitz, and T. Katzner. 2015. Chronic lead exposure is epidemic in obligate scavenger populations in eastern North America. Environment International 79: 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.03.010.

Bellrose, F.C. 1959. Lead poisoning as a mortality factor in waterfowl populations. Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin. 27: 235–288.

Berny, P.J., E. Mas, and D. Vey. 2017. Embedded lead shots in birds of prey: The hidden threat. European Journal of Wildlife Research 63: 101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-017-1160-z.

Berny, P., L. Vilagines, J.M. Cugnasse, O. Mastain, J.Y. Chollet, G. Joncour, and M. Razin. 2015. Vigilance poison: Illegal poisoning and lead intoxication are the main factors affecting avian scavenger survival in the Pyrenees (France). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 118: 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.04.003.

Bingham, R.J., R.T. Larsen, J.A. Bissonette, and J.O. Hall. 2015. Widespread ingestion of lead pellets by wild chukars in northwestern Utah. Wildlife Society Bulletin 39: 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.527.

Binkowski, Ł.J., W. Meissner, M. Trzeciak, K. Izevbekhai, and J. Barker. 2016. Lead isotope ratio measurements as indicators for the source of lead poisoning in mute swans (Cygnus olor) wintering in Puck Bay (northern Poland). Chemosphere 164: 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.120.

BirdLife International. 2015. Aythya ferina. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T22680358A59966548. Retrieved 04 October, 2018, from https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22680358/59966548.

BirdLife International. 2018. Species factsheet: Clanga clanga. Retrieved 09 October, 2018, from http://datazone.birdlife.org/index.php/species/factsheet/greater-spotted-eagle-clanga-clanga/text.

Calvert, H.S. 1876. Pheasants poisoned by swallowing shot. The Field 47: 189.

Carneiro, M.A., P.A. Oliveira, R. Brandão, O.N. Francisco, R. Velarde, S. Lavín, and B. Colaço. 2016. Lead poisoning due to lead-pellet ingestion in griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus) from the Iberian Peninsula. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 30: 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1647/2014-051.

Carneiro, M., B. Colaço, R. Brandão, B. Azorín, O. Nicolas, J. Colaço, M.J. Pires, S. Agustí, et al. 2015. Assessment of the exposure to heavy metals in Griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus) from the Iberian Peninsula. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 113: 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.12.016.

Carneiro, M., B. Colaço, R. Brandão, C. Ferreira, N. Santos, V. Soeiro, A. Colaço, M.J. Pires, et al. 2014. Biomonitoring of heavy metals (Cd, Hg, and Pb) and metalloid (As) with the Portuguese common buzzard (Buteo buteo). Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 186: 7011–7021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-014-3906-3.

Clausen, K.K., T.E. Holm, L. Haugaard, and J. Madsen. 2017. Crippling ratio: A novel approach to assess hunting-induced wounding of wild animals. Ecological Indicators 80: 242–246.

Cromie, R., J. Newth, J. Reeves, M. O’Brien, K. Beckmann, and M. Brown. 2015. The sociological and political aspects of reducing lead poisoning from ammunition in the UK: why the apparently simple solution is so difficult. In Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead ammunition: understanding and minimising the risks to human and environmental health, eds. R.J. Delahay, and C.J. Spray, pp. 104–124. Edward Grey Institute, University of Oxford.

Cruz-Martinez, L., M.D. Grund, and P.T. Redig. 2015. Quantitative assessment of bullet fragments in viscera of sheep carcasses as surrogates for white-tailed deer. Human-Wildlife Interactions 9: 211–218.

Delahay R.J., and C.J. Spray (Eds.) 2015. Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium: Lead Ammunition: Understanding and Minimizing the Risks to Human and Environmental Health, 152 pp. Oxford University, Edward Grey Institute.

DEFRA. 2013. Great Britain poultry register statistics: 2013. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Retrieved March, 2018, from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/314715/pub-avian-gbpr13.pdf (Accessed March 2018).

Descalzo, E., and R. Mateo. 2018. La contaminación por munición de plomo en Europa: el plumbismo aviary las implicaciones en la seguridad de la carne de caza. Instituto de Investigación en Recursos Cinegéticos (IREC), Ciudad Real, España. 82 pp. http://www.irec.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Descalzo-y-Mateo-2018-Revision-Plomo-Europa.pdf.

ECHA. 2017. European Chemicals Agency Annex XV restriction report—lead in shot, 96 pp. https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/6ef877d5-94b7-a8f8-1c49-8c07c894fff7.

Ecke, F., N.J. Singh, J.M. Arnemo, A. Bignert, B. Helander, Å.M.M. Berglund, H. Borg, C. Bröjer, et al. 2017. Sublethal lead exposure alters movement behavior in free-ranging golden eagles. Environmental Science and Technology 51: 5729–5736. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b06024.

EFSA. 2010. Scientific opinion on lead in food. EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). EFSA Journal. 8(4): 1570. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1570. Retrieved March, 2018, from: http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1570.

Eid, R., D.S.M. Guzman, K.A. Keller, K.T. Wiggans, C.J. Murphy, E.E.B. LaDouceur, M.K. Keel, and C.M. Reilly. 2016. Choroidal vasculopathy and retinal detachment in a bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) with lead toxicosis. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 30: 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1647/2015122.

Eisler, R. 1988. Lead hazards to fish, wildlife, and invertebrates: a synoptic review. Contaminant Hazard Reviews. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report, 85 (1.14).

Ellam, R.M. 2010. The graphical presentation of lead isotope data for environmental source apportionment. Science of the Total Environment 408: 3490–3492.

Ertl, K., R. Kitzer, and W. Goessler. 2016. Elemental composition of game meat from Austria. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part B 9: 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/19393210.2016.1151464.

Espín, S., E. Martínez-López, P. Jiménez, P. María-Mojica, and A.J. García-Fernández. 2014. Effects of heavy metals on biomarkers for oxidative stress in Griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus). Environmental Research 129: 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2013.11.008.

Ferreyra, H., P.M. Beldomenico, K. Marchese, M. Romano, A. Caselli, A.I. Correa, and M. Uhart. 2015. Lead exposure affects health indices in free-ranging ducks in Argentina. Ecotoxicology 24: 735–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-015-1419-7.

Ferreyra, H., M. Romano, P. Beldomenico, A. Caselli, A. Correa, and M. Uhart. 2014. Lead gunshot pellet ingestion and tissue lead levels in wild ducks from Argentine hunting hotspots. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 103: 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.10.015.

Finkelstein, M.E., J. Brandt, E. Sandhaus, J. Grantham, A. Mee, P.J. Schuppert, and D.R. Smith. 2015. Lead exposure risk from trash ingestion by the endangered California condor (Gymnogyps californianus). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 51: 901–906. https://doi.org/10.7589/2014-10-253.

Finkelstein, M.E., Z.E. Kuspa, A. Welch, C. Eng, M. Clark, J. Burnett, and D.R. Smith. 2014. Linking cases of illegal shootings of the endangered California condor using stable lead isotope analysis. Environmental Research 134: 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.07.022.

Flint, P.L., J.B. Grand, M.R. Petersen, and R.F. Rockwell. 2016. Effects of lead exposure, environmental conditions, and metapopulation processes on population dynamics of spectacled eiders. North American Fauna. 81: 1–41. https://doi.org/10.3996/nafa.81.0001.

Franson, J.C., and D.J. Pain. 2011. Lead in birds. In Environmental contaminants in biota: Interpreting tissue concentrations, ed. W.N. Beyer and J.P. Meador, 563–593. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis Group.

Friend, M., and C.J. Franson. (Eds). 1999. Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, ITR 1999-001 National Wildlife Health Center, 6006 Schroeder Rd., Madison, WI 53711 https://www.nwhc.usgs.gov/publications/field_manual/field_manual_of_wildlife_diseases.pdf.

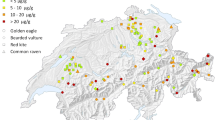

Ganz, K., L. Jenni, M.M. Madry, T. Kraemer, H. Jenny, and D. Jenny. 2018. Acute and chronic lead exposure in four avian scavenger species in Switzerland. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 75: 566–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-018-0561-7.

Garbett, R., G. Maude, P. Hancock, D. Kenny, D. Reading, and A. Amar. 2018. Association between hunting and elevated blood lead levels in the critically endangered African white-backed vulture Gyps africanus. Science of the Total Environment 630: 1654–1665. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969718306193?via%3Dihub.

Gasparik, J., J. Venglarcik, J. Slamecka, R. Kropil, P. Smehyl, and J. Kopecky. 2012. Distribution of lead in selected organs and its effect on reproduction parameters of pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) after an experimental per oral administration. Journal of Environmental Science and Health: Part A 47: 1267–1271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934529.2012.672127.

Gil-Sánchez, J.M., S. Molleda, J.A. Sánchez-Zapata, J. Bautista, I. Navas, R. Godinho, A.J. García-Fernández, and M. Moleón. 2018. From sport hunting to breeding success: Patterns of lead ammunition ingestion and its effects on an endangered raptor. Science of the Total Environment 613: 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.069.

Golden, N.H., S.E. Warner, and M.J. Coffey. 2016. A review and assessment of spent lead ammunition and its exposure and effects to scavenging birds in the United States. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, eds. W. de Voogt, 237: 123–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23573-8_6.

González, F., I. López, L. Suarez, V. Moraleda, and C. Rodríguez. 2017. Levels of blood lead in griffon vultures from a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Spain. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 143: 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.05.010.

Grade, T.J., M.A. Pokras, E.M. Laflamme, and H.S. Vogel. 2018. Population-level effects of lead fishing tackle on common loons. Journal of Wildlife Management 82: 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21348.

Green, R.E., W.G. Hunt, C.N. Parish, and I. Newton. 2008. Effectiveness of action to reduce exposure of free-ranging California condors in Arizona and Utah to lead from spent ammunition. PLoS ONE 3: e4022. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004022.

Green, R.E., and D.J. Pain. 2016. Possible effects of ingested lead gunshot on populations of ducks wintering in the UK. Ibis 158: 699–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.1400.

Group of Scientists. 2013. Health risks from lead-based ammunition in the environment: A consensus statement of scientists. Retrieved March, 2018, from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6dq3h64x.

Group of Scientists. 2014. Wildlife and human health risks from lead-based ammunition in Europe: a consensus statement by scientists. Retrieved March, 2018, from: http://www.zoo.cam.ac.uk/leadammuntionstatement/ (Accessed March 2018).

Herring, G., C.A. Eagles-Smith, and M.T. Wagner. 2016. Ground squirrel shooting and potential lead exposure in breeding avian scavengers. PLoS ONE 11: e0167926. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167926.

Hivert, L.G., J.R. Clarke, S.J. Peck, C. Lawrence, W.E. Brown, S. Huxtable, D. Schaap, D. Pemberton, et al. 2018. High blood lead concentrations in captive Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii): A threat to the conservation of the species? Australian Veterinary Journal 96: 442–449.

Horowitz, I.H., E. Yanco, R.V. Nadler, N. Anglister, S. Landau, R. Elias, A. Lublin, S. Perl, et al. 2014. Acute lead poisoning in a griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus) in Israel. Israel Journal of Veterinary Medicine 69: 163–168.

Ishii, C., S.M.M. Nakayama, Y. Ikenaka, H. Nakata, K. Saito, Y. Watanabe, H. Mizukawa, S. Tanabe, et al. 2017. Lead exposure in raptors from Japan and source identification using Pb stable isotope ratios. Chemosphere 186: 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.07.143.

Isomursu, M., J. Koivusaari, T. Stjernberg, V. Hirvelä-Koski, and E.R. Venäläinen. 2018. Lead poisoning and other human-related factors cause significant mortality in white-tailed eagles. Ambio 47: 858–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1052-9.

Jenni, L., M.M. Madry, T. Kraemer, J. Kupper, H. Naegeli, H. Jenny, and D. Jenny. 2015. The frequency distribution of lead concentration in feathers, blood, bone, kidney and liver of golden eagles Aquila chrysaetos: Insights into the modes of uptake. Journal of Ornithology 156: 1095–1103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-015-1220-7.

Kalisinska, E., N. Lanocha-Arendarczyk, D. Kosik-Bogacka, H. Budis, J. Podlasinska, M. Popiolek, A. Pirog, and E. Jedrzejewska. 2016. Brains of native and alien mesocarnivores in biomonitoring of toxic metals in Europe. PLoS ONE 11: e0159935. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159935.

Kanstrup, N., J. Swift, D.A. Stroud, and M. Lewis. 2018. Hunting with lead ammunition is not sustainable: European perspectives. Ambio 47: 846–857.

Kelly, A., and S. Kelly. 2005. Are mute swans with elevated blood lead levels more likely to collide with overhead power lines? Waterbirds 28: 331–334. https://doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2005)028%5b0331:AMSWEB%5d2.0.CO;2.

Kirby, J., S. Delany, and J. Quinn. 1994. Mute swans in Great Britain: A review, current status and long-term trends. Hydrobiologia 279: 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00027878.

Kitowski, I., A. Sujak, D. Wiącek, W. Strobel, A. Komosa, and M. Stobiński. 2016. Heavy metals in livers of raptors from Eastern Poland: The importance of diet composition. Belgian Journal of Zoology 146: 3–13.

Kitowski, I., D. Jakubas, D. Wiącek, and A. Sujak. 2017a. Concentrations of lead and other elements in the liver of the white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla), a European flagship species, wintering in Eastern Poland. Ambio 46: 825–841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0929-3.

Kitowski, I., D. Wiacek, A. Sujak, A. Komosa, and M. Świetlicki. 2017b. Factors affecting trace element accumulation in livers of avian species from East Poland. Turkish Journal of Zoology 41: 901–913.

Kitowski, I., A. Sujak, D. Wiącek, and A. Komosa. 2017c. Ecological factors helping to avoid the toxic element accumulation in livers of the lesser spotted eagle (Clanga pomarina Brehm) from Eastern Poland. Journal of Elementology 22: 305–314. https://doi.org/10.5601/jelem.2015.20.2.928.

Koeppel, K.N., and L.V. Kemp. 2015. Lead toxicosis in a southern ground hornbill Bucorvus leadbeateri in South Africa. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 29: 340–344. https://doi.org/10.1647/2014-037.

LaDouceur, E.E., R. Kagan, M. Scanlan, and T. Viner. 2015. Chronically embedded lead projectiles in wildlife: A case series investigating the potential for lead toxicosis. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 46: 438–442.

LAG. 2015. Lead Ammunition, Wildlife and Human Health. A report prepared for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and the Food Standards Agency in the United Kingdom. Available at: http://www.leadammunitiongroup.org.uk/reports/ and Appendices http://www.leadammunitiongroup.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/LAG-Report-June-2015-Appendices-without-Appendix-6.pdf.

Lambertucci, S.A., J.A. Donázar, A.D. Huertas, B. Jiménez, M. Sáez, J.A. Sanchez-Zapata, and F. Hiraldo. 2011. Widening the problem of lead poisoning to a South-American top scavenger: Lead concentrations in feathers of wild Andean condors. Biological Conservation 144: 1464–1471.

Langner, H.W., R. Domenech, V.A. Slabe, and S.P. Sullivan. 2015. Lead and mercury in fall migrant golden eagles from western North America. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 69: 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-015-0139-6.

Larkman, A., I. Newton, R.E. Feber, and D. Macdonald. 2015. Small farmland bird declines, and changes in seed sources. In Wildlife Conservation on Farmland, eds. D.W. Macdonald, and R.E. Feber, pp. 181–202. Oxford University Press.

Legagneux, P., P. Suffice, J.S. Messier, F. Lelievre, J.A. Tremblay, C. Maisonneuve, R. Saint-Louis, and J. Bety. 2014. High risk of lead contamination for scavengers in an area with high moose hunting success. PLoS ONE 9: e111546. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111546.

Lindblom, R.A., L.M. Reichart, B.A. Mandernack, M. Solensky, C.W. Schoenebeck, and P.T. Redig. 2017. Influence of snowfall on blood lead levels of free-flying bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) in the Upper Mississippi River Valley. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 53: 816–823. https://doi.org/10.7589/2017-02-027.

Madry, M.M., T. Kraemer, J. Kupper, H. Naegeli, H. Jenny, L. Jenni, and D. Jenny. 2015. Excessive lead burden among golden eagles in the Swiss Alps. Environmental Research Letters 10: 034003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/3/034003.

Madsen, J., and H. Noer. 1996. Decreased survival of pink-footed geese Anser brachyrhynchus carrying shotgun pellets. Wildlife Biology 2: 75–82.

Mariussen, E., L.S. Heier, H.C. Teienb, M.N. Pettersen, T.F. Holth, B. Salbub, and B.O. Rosselande. 2017. Accumulation of lead (Pb) in brown trout (Salmo trutta) from a lake downstream a former shooting range. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 135: 327–336.

Martin, P.A., K.D. Hughes, G.D. Campbell, and J.L. Shutt. 2018. Metals and organohalogen contaminants in Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) from Ontario, 1991–2008. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 74: 305–317.

Mateo, R. 2009. Lead poisoning in wild birds in Europe and the regulations adopted by different countries. In Ingestion of lead from spent ammunition: Implications for wildlife and humans, ed. R.T. Watson, M. Fuller, M. Pokras, and W.G. Hunt, 71–98. Boise: The Peregrine Fund.

Mateo, R., R. Cadenas, M. Máñez, and R. Guitart. 2001. Lead shot ingestion in two raptor species from Doñana, Spain. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 48: 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1006/eesa.2000.1996.

Mateo, R., N. Vallverdú Coll, and M.E. Ortiz Santaliestra. 2013. Intoxicación por munición de plomo en aves silvestres en España y medidas para reducir el riesgo. Ecosistemas 22: 61–67.

Mateo, R., N. Petkov, A. Lopez-Antia, J. Rodríguez-Estival, and A.J. Green. 2016. Risk assessment of lead poisoning and pesticide exposure in the declining population of red-breasted goose (Branta ruficollis) wintering in Eastern Europe. Environmental Research 151: 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.07.017.

Mateo, R., N. Vallverdú-Coll, A. López-Antia, M.A. Taggart, M. Martínez-Haro, R. Guitart, and M.E. Ortiz-Santaliestra. 2014. Reducing Pb poisoning in birds and Pb exposure in game meat consumers: The dual benefit of effective Pb shot regulation. Environment International 63: 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2013.11.006.

Mateo-Tomás, P., P.P. Olea, M. Jiménez-Moreno, P.R. Camarero, I.S. Sánchez-Barbudo, R.C. Rodríguez Martin-Doimeadios, and R. Mateo. 2016. Mapping the spatio-temporal risk of lead exposure in apex species for more effective mitigation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283: 20160662. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0662.

Merkel, F.R., K. Falk, and S.E. Jamieson. 2006. Effect of embedded lead shot on body condition of common eiders. Journal of Wildlife Management 70: 1644–1649. https://doi.org/10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70%5b1644:EOELSO%5d2.0.CO;2.

Meyer, C.B., J.S. Meyer, A.B. Francisco, J. Holder, and F. Verdonck. 2016. Can ingestion of lead shot and poisons change population trends of three European birds: Grey partridge, common buzzard, and red kite? PLoS ONE 11: e0147189. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147189.

Molenaar, F.M., J.E. Jaffe, I. Carter, E.A. Barnett, R.F. Shore, J.M. Rowcliffe, and A.W. Sainsbury. 2017. Poisoning of reintroduced red kites (Milvus milvus) in England. European Journal of Wildlife Research 63: 94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-017-1152-z.

Nadjafzadeh, M., H. Hofer, and O. Krone. 2015. Lead exposure and food processing in white-tailed eagles and other scavengers: An experimental approach to simulate lead uptake at shot mammalian carcasses. European Journal of Wildlife Research 61: 763–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-015-0953-1.

Naidoo, V., K. Wolter, and C.J. Botha. 2017. Lead ingestion as a potential contributing factor to the decline in vulture populations in southern Africa. Environmental Research 152: 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.10.013.

Newth, J.L., E.C. Rees, R.L. Cromie, R.A. McDonald, S. Bearhop, D.J. Pain, G.J. Norton, C. Deacon, et al. 2016. Widespread exposure to lead affects the body condition of free-living whooper swans Cygnus cygnus wintering in Britain. Environmental Pollution 209: 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.11.007.

Nichols, J.D., F.A. Johnson, B.K. Williams, and G.S. Boomer. 2015. On formally integrating science and policy: Walking the walk. Journal of Applied Ecology 52: 539–543.

North, M.A., E.P. Lane, K. Marnewick, P. Caldwell, G. Carlisle, and L.C. Hoffman. 2015. Suspected lead poisoning in two captive cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus jubatus) in South Africa, in 2008 and 2013. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association 86: 1286. https://doi.org/10.4102/jsava.v86i1.1286.

O’Donoghue, B. 2017. R.A.P.T.O.R. Recording and Addressing Persecution and Threats to Our Raptors. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. https://www.npws.ie/sites/default/files/publications/pdf/2017-raptor-report.pdf.

O’Halloran, J., A.A. Myers, and P.F. Duggan. 1988. Lead poisoning in swans and sources of contamination in Ireland. Journal of Zoology 216: 211–223.

Pain, D. J. (ed.). 1992. Lead Poisoning in Waterfowl. Proc. IWRB Workshop, Brussels, Belgium 1991. IWRB Spec. Publ. 16, Slimbridge UK.

Pain, D.J., J.J. Fisher, and V.G. Thomas. 2009. A global update of lead poisoning in terrestrial birds from ammunition sources. In Ingestion of Lead from Spent Ammunition: Implications for Wildlife and Humans, eds. R.T. Watson, M. Fuller, M. Pokras, W.G. Hunt, pp. 289–301. Boise: The Peregrine Fund

Pain, D.J., and R.E. Green. 2015. An evaluation of the risks to wildlife in the UK from lead derived from ammunition. A report to the UK Government, 120 p. http://www.leadammunitiongroup.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/LAG-Report-June2015-Appendices-without-Appendix-6.pdf

Pain, D. J., R. Cromie, and R.E. Green. 2015. Poisoning of birds and other wildlife from ammunition-derived lead in the UK. In Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead ammunition: understanding and minimising the risks to human and environmental health, eds., R.J. Delahay, and C.J. Spray, pp. 58–84. Edward Grey Institute, University of Oxford.

Pattee, O., and D. Pain. 2003. Lead in the environment. In Handbook of ecotoxicology, eds. D.J. Hoffman, B.A. Rattner, G.A. Burton Jr., and J. Cairns Jr, Second ed., pp. 373–408. Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press.

Perrins, C.M., G. Cousquer, and J. Waine. 2003. A survey of blood lead levels in mute swans Cygnus olor. Avian Pathology 32: 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307946021000071597.

Pineau, A., B. Fauconneau, E. Plouzeau, B. Fernandez, N. Quellard, P. Levillain, and O. Guillard. 2017. Ultrastructural study of liver and lead tissue concentrations in young mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) after ingestion of single lead shot. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health-Part A-Current Issues 80: 188–195.

Provencher, J.F., M.R. Forbes, H.L. Hennin, O.P. Love, B.M. Braune, M.L. Mallory, and H.G. Gilchrist. 2016. Implications of mercury and lead concentrations on breeding physiology and phenology in an Arctic bird. Environmental Pollution 218: 1014–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.08.052.

Rendon Act. 2013. Assembly Bill No. 711. CHAPTER 742 An act to amend Section 3004.5 of the Fish and Game Code, relating to hunting. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140AB711.

Rodríguez-Seijo, A., A. Cachada, A. Gavina, A.C. Duarte, F.A. Vega, M.L. Andrade, and R. Pereira. 2017. Lead and PAHs contamination of an old shooting range: A case study with a holistic approach. Science of the Total Environment 575: 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.018.

Runia, T.J., and A.J. Solem. 2016. Spent lead shot availability and ingestion by ring-necked pheasants in South Dakota. Wildlife Society Bulletin 40: 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.681.

Runia, T.J., and A.J. Solem. 2017. Pheasant response to lead ingestion. The Prairie Naturalist 49: 13–18.

Russell, R.E., and J.C. Franson. 2014. Causes of mortality in eagles submitted to the National Wildlife Health Center 1975–2013. Wildlife Society Bulletin 38: 697–704. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.469.

Sinkakarimi, M.H., A.R. Pourkhabbaz, M. Hassanpour, and J.M. Levengood. 2015. Study on metal concentrations in tissues of Mallard and Pochard from two major wintering sites in Southeastern Caspian Sea, Iran. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 95: 292–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-015-1591-8.

Sinkakarimi, M.H., L.J. Binkowski, M. Hassanpour, R. Ghasem, M. Ahmadpour, and J. Levengood. 2018. Metal concentrations in tissues of Gadwall and common teal from Miankaleh and Gomishan international wetlands, Iran. Biological Trace Element Research 185: 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-017-1237-2.

Sears, J., and A. Hunt. 1991. Lead poisoning in mute swans, Cygnus olor, in England. Wildfowl Supplement 1: 383–388.

Stroud, D.A. 2015. Regulation of some sources of lead poisoning: a brief review. pp 8-26. In Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium: Lead Ammunition: Understanding and Minimizing the Risks to Human and Environmental Health, eds., R.J. Delahay, and C.J. Spray, 152 pp. Oxford University: Edward Grey Institute.

Tannenbaum, L. 2012. Evidence of high tolerance to ecologically relevant lead shot pellet exposures by an upland bird. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment 20: 479–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/10807039.2012.746143.

Tavecchia, G., R. Pradel, J.D. Lebreton, A.R. Johnson, and J.Y. Mondain-Monval. 2001. The effect of lead exposure on survival of adult mallards in the Camargue, southern France. Journal of Applied Ecology 38: 1197–1207. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0021-8901.2001.00684.x.

Truss, E. 2016. Letter from Elizabeth Truss to John Swift. Retrieved 12 January, 2019, from: http://www.leadammunitiongroup.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Letter-from-Elizabeth-Truss-to-John-Swift-13-July-2016.pdf.

Vallverdú-Coll, N., M.E. Ortiz-Santaliestra, F. Mougeot, D. Vidal, and R. Mateo. 2015a. Sublethal Pb exposure produces season-dependent effects on immune response, oxidative balance and investment in carotenoid-based coloration in red-legged partridges. Environmental Science and Technology 49: 3839–3850. https://doi.org/10.1021/es505148d.

Vallverdú-Coll, N., A. López-Antia, M. Martinez-Haro, M.E. Ortiz-Santaliestra, and R. Mateo. 2015b. Altered immune response in mallard ducklings exposed to lead through maternal transfer in the wild. Environmental Pollution 205: 350–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.06.014.

Vallverdú-Coll, N., F. Mougeot, M.E. Ortiz-Santaliestra, C. Castaño, J. Santiago-Moreno, and R. Mateo. 2016a. Effects of lead exposure on sperm quality and reproductive success in an avian model. Environmental Science and Technology 50: 12484–12492. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b04231.

Vallverdú-Coll, N., F. Mougeot, M.E. Ortiz-Santaliestra, J. Rodriguez-Estival, A. López-Antia, and R. Mateo. 2016b. Lead exposure reduces carotenoid-based coloration and constitutive immunity in wild mallards. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 35: 1516–1525. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.330.

Warner, S.E., E.E. Britton, D.N. Becker, and M.J. Coffey. 2014. Bald eagle lead exposure in the Upper Midwest. Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management 5: 208–216. https://doi.org/10.3996/032013-JFWM-029.

Watson, R.T., M. Fuller, M. Pokras, and W. Hunt. (eds). 2009. Proceedings of the conference ingestion of lead from spent ammunition: implications for wildlife and humans. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, ID, USA.

Weiss, D., C.D. Tomasallo, G. Meiman, W. Alarcon, N.M. Grabe, K.M. Bisgard, and H.A. Anderson. 2017. Elevated blood lead levels associated with retained bullet fragments: United States, 2003–2012 MMWR-Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66: 130–133.

West, C.J., J.D. Wolfe, A. Wiegardt, and T. Williams-Claussen. 2017. Feasibility of California condor recovery in northern California, USA: Contaminants in surrogate turkey vultures and common ravens. Condor 119: 720–731. https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-17-48.1.