Abstract

Cadmium-resistant strains psychrotolerant Pseudomonas putida SB32 and alkalophilic Pseudomonas monteilli SB35 were originally isolated from the soil of Semera mines, Palamau, Jharkhand, India. Further, to unravel the mechanism involved in cadmium resistance, plasmid DNA was isolated from the strains and subjected to amplification of the czc gene, which is responsible for the efflux of three metal cations, viz. Co, Zn and Cd, from the cell. Furthermore, the amplicon was cloned into pDrive cloning vector and sequenced. When compared with the available database, the sequence homology of the cloned gene showed the presence of a partial czcA gene sequence, thereby indicating the presence of a plasmid-mediated efflux mechanism for resistance in both strains. These results were further confirmed by atomic absorption spectroscopy and transmission electron microscopy. Moreover, the strains were characterized functionally for their bioremediation potential in cadmium-contaminated soil by performing an in situ experiment using soybean plant. A marked increase in agronomical parameters was observed in presence of both strains. Further, the concentration of metal ions decreased in both plants and soil in the presence of these bioinoculants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Naturally occurring bacteria that are capable of metal accumulation have been extensively studied since it is difficult to imagine that a single bacterium would remove all heavy metals from its polluted site (Clausen 2000). Therefore, diversified microorganisms have to be classified morphologically, physiologically and biochemically to understand their taxonomical variation and evolutionary distance from the parental linage.

Cadmium is a non-redox metal unable to produce active oxygen species (AOS) via Fenton and IQ Haber–Weiss reaction (Sanita Di Toppi and Gabbrielli 1999). However, several reports demonstrate that Cd can indirectly promote the generation of AOS (Sandalio et al. 2001). Cadmium-increased lipid peroxidation has been demonstrated in Phaseolus vulgaris roots and leaves (Chaoui et al. 1997). When accumulated in the plant tissue, it causes alteration in catalytic efficacy of enzymes (Somashekaraiah et al. 1992; Romero-Puertas et al. 1999; Piqueras et al. 1999), damage to the cellular membranes (Tu and Brovillett 1987) and inhibits the root growth. This metal enters the environment mainly from fertilizers and is transferred to animals and humans through industrial processes (Wagner 1993) leading to serious damage to human health (Alloway 1990). It affects cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and increases oncogene activation to carcinogenesis (Naidu et al. 1997).

Microbial survival in polluted soil depends on intrinsic biochemical and structural properties, physiological and/or genetic adaptations including morphological changes in cells and environmental modifications of metal speciation (Wuertz and Mergeay 1997). Microbes apply various types of resistance mechanisms in response to heavy metals (Nies 2003). Microbial methods of environment purification and cleanup are known to be the most promising because of their safety, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness (He et al. 2011). Many microorganisms can absorb and concentrate heavy metals thus, providing resistance (Burke and Pfister 1986). On the other hand, studying metal ion resistances give us important insights into environmental processes and provide an understanding of basic living processes. Furthermore, genes for resistance to inorganic salts of soft metals are found both on plasmids and in chromosomes. The physiological role of plasmid-encoded determinants is generally to confer resistance; however, mostly chromosomally encoded systems may include metal ion homeostasis (Wuertz and Mergeay 1997).

Two well-studied genetic mechanisms of metal resistance in bacteria include heavy metal efflux systems (Nies and Silver 1995) and the presence of metal binding proteins (Robinson et al. 1990). Many operons of efflux system are known. In the Gram-positive bacteria, the plasmid-encoded Cd efflux system, called the CadA resistance system, utilizes the CadA protein, which is a P-type ATPase (Tsai and Linet 1993). However, Cd resistance in Gram-negative organisms is due to a multi-protein chemiosmotic antiport system (Silver 1996). Primarily, the czc system detoxifies the cell by cation efflux, the three metal cations, viz. cobalt, zinc and cadmium, which are taken up into the cell by fast and unspecific transport system for Mg2+ are actively extruded from cell by products of czc resistance determinants (Nies et al. 1989b). The protein complex is composed of three subunits, czcC, czcB and czcA (Nies et al. 1989a). CzcA is a RND protein (Tseng et al. 1999) and contains two hydrophilic domains, which are located in the periplasm (Goldberg et al. 1999), as the other two subunits of czc complex, czcB and czcC. There are at least six regulatory proteins (CzcD, CzcR, CzcS, CzcN, CzcI and an unknown sigma factor, “RpoX”) involved in regulation of the three structural genes czcCBA. The proteins czcA and czcB alone are capable of pumping zinc ions out of the cell, even if czcC is not present (Nies et al. 1989b). Therefore, czcA is proposed to function as the actual efflux-transportation protein; however, czcA’s specificity for exportation of these ions is apparently regulated by the presence of two other structural proteins (Nies and Silver 1995). The cell surfaces of all microorganisms are negatively charged due to the presence of various anionic structures which gives bacteria the ability to bind metal cations. So, isolation of heavy metal-resistant bacteria may be useful to improve the application of microorganism in environment protection.

In this study, an effort has been made to unravel the mechanism involved in Cd resistance in psychrotolerant P. putida SB32 and alkalophilic P. monteilli SB35. This includes molecular characterization of the strains to identify the location of czc gene and to find out whether the resistance to Cd was due to efflux mechanism or due to accumulation of metal in the bacterial cell. Furthermore, in situ trials on soybean plant in presence of the two isolates were performed to analyze the bioremediation potential of strains.

Materials and methods

Isolation of Cd-resistant extremophilic isolates

Psychrotolerants P. putida SB32 and alkalophilic P. monteilli SB35 strains were isolated from the soil sample of Semera Mines, Palamau, Jharkhand, India. The strains were grown in nutrient broth (Himedia Laboratories Private Limited, Mumbai, India) containing 1 mM cadmium chloride (CdCl2) and was kept overnight at 30 °C. Furthermore, the grown culture was also streaked on nutrient agar plates (Himedia Laboratories) and the plates were kept at 4 °C until further use. They were optimized for their respective parameters, i.e., temperature for psychrotolerant P. putida SB32 (optimum growth at 20 °C) and pH for alkalophilic P. monteilli SB35 (pH optima 9.0) and are found to be possessing high resistance to Cd.

Plasmid and genomic DNA isolation

The plasmid DNA was isolated using previously described protocol (Anderson and McKay 1983) and genomic DNA by Qiagen Bacterial genomic DNA isolation kit, Hilden, Germany. The isolated DNA was made to run on 0.8 % agarose gel and visualized subsequently.

Amplification of czc gene

The czc gene was amplified from both plasmid and genomic DNA of strains SB32 and SB35 using primers czcF (AAC CAG ATC TCG CGC GAG AAC) and czcR (CGG CAACAC CAG TAG GGT CAG). Polymerase chain reaction (50 μl) mixture contained 0.5 μM of each primer, 200 μM dNTPS, 1.0 U Taq DNA Polmerase, PCR buffer supplied with the enzyme and 1 μl (75 ng) of template DNA. The total volume of the reaction mixture was maintained with sterilized triple distilled water. PCR was performed in ‘BioRad iQTM5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system’ and was carried out as follows: a single denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min followed by a 36-cycle program which included denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 61.6 °C for 30 s and extension 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

Cloning and sequencing of PCR products

The purified products of czc gene were ligated with pDrive vector overnight at 4 °C using Qiagen cloning kit, Hilden, Germany and were transformed into E.coli DH5α. DNA sequencing of single pass of czc gene was done using primer T7. The sequence thus obtained was analyzed using BLASTn search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast).

Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

To confirm efflux or intracellular accumulation of metal, AAS studies were done by combining the protocols given by Roane et al. 2001 and Vasudevan et al. 2001. The strains (SB32 and SB35) were grown both in the presence and absence (control) of 0.1 mM CdCl2 and 25 ml of sample was drawn at different intervals of time, i.e., during the lag, log, stationary and death phase. The samples were centrifuged at 7,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and passed through 0.22 μm pore size filters with the help of 10 ml disposables syringe and stored at 4 °C for further metal analysis by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The pellets were dried overnight at 90 °C in the oven and weight was noted. The dried pellets (4–200 mg) were then acid lysed overnight by 5 ml concentrated HNO3 and incinerated on sand bath for 4–6 h at slow heating (45–50 °C). Further, 1 ml of concentrated HNO3 and per-chloric acid (60 %) in the ratio 6:1 was added and again kept for incineration on sand bath for 3 h till white residue is formed. The white residue was dissolved in 50 ml of deionized water. The concentration of Cd was determined by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer at 228 nm with lamp current 3 mA.

Consequently, samples of both control and treated cells were drawn during the late log phase for TEM analysis. The strains were grown in 25 ml nutrient broth in the presence and absence of 0.1 mM CdCl2 and 5.0 ml sample from each experimental flask was drawn after 24 h. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed with 5 ml PBS (pH 7.4, 0.1 M) for four times. Centrifugation was done at 8,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The pelleted cells were fixed overnight in 1 ml fixative [2.5 % glutaraldehyde and 2 % paraformaldehyde in (pH 7.4) sodium phosphate buffer] and rinsed twice with phosphate buffer for 1 h. Further, the samples were washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer saline at pH 7.4 for 15 min and then fixed for 1 h at room temperature in 1 % osmium tetraoxide. The samples were dehydrated in three changes of 50 % alcohol for 15 min, four changes of absolute alcohol for 15 min and two changes of 100 % toluene for 30 min each, before being transferred to a mixture of equal parts of araldite and toluene overnight at room temperature. Impregnation was carried out in the fresh change of araldite and continued for 2 days. The samples were finally embedded in fresh araldite and polymerized for 3 days. The ultra thin sections (70–80 nm) were cut on a microtome and mounted on uncoated copper grids. The sections were stained in a saturated solution of uranyl acetate in 50 % alcohol for 15 min followed by lead citrate for 15 min and examined in 100 kV transmission electron microscope (JEOL, JEM 1011).

In situ characterization

Seeds were sown in the pot filled with alkaline soil (pH was approximately 8.6 ± 0.2). To detect the remediation ability of strains and subsequent effect to soybean, 124 μM CdCl2 was added to the soil (whereas, the bacterial strains used in this study can tolerate much higher concentration, but at the concentration >124 μM, plants were unable to grow even in presence of bioinoculants). Each treatment was taken individually as indicated below:

-

1.

Uninoculated soil (control)

-

2.

Uninoculated soil with Cd

-

3.

Inoculated soil with SB35

-

4.

Inoculated with SB35 in Cd-contaminated soil

-

5.

Inoculated soil with SB32

-

6.

Inoculated with SB32 in Cd-contaminated soil

The inoculated pots of soybean were kept in net house at a temperature of 30 ± 5 °C. Pots were irrigated with tap water to maintain moisture content. Fifteen seeds were sown per pot, with three replicates per treatment. Plants were uprooted after 60 days of cultivation. Plant height and wet weight were measured before the plant biomass was oven dried. The agronomical parameters of plant were measured after harvesting.

Heavy metal analysis

Plant materials

Plants were harvested and roots were washed extensively in several changes of a solution containing 5 mM Tris HCl (pH 6.0) and 5 mM EDTA, and then distilled water to remove non-specifically bound metal ions. Shoots and roots were oven dried separately at 60 °C for 24 h followed by 70 °C for 3 h. Aliquots (1 g) of dried leaves were ground in a porcelain mortar while dried roots were extensively minced with a razor blade and then the samples were analyzed by modified methods of wet ashing (Burd et al. 2000). Wet ashing was performed by placing aliquots of dried material in 10 ml of concentrated nitric acid at 70 °C till the brown vapor subsides. Subsequently, 10 ml of diacid mixture (HNO3 and HClO4, 3:1 ratio) was added and left till they reduced to 1 ml. Later 5 ml of 6 NHCl for 1 h was added and cooled. The digested samples were brought to 50 ml with deionized water and heavy metal analysis was done using a flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The instrument was zeroed with 1 % HNO3 blanks. Samples in triplicate were taken.

Soil

Soil samples were collected periodically and analyzed for residual Cd concentration. To analyze heavy metals contents in soil, 10 g of dried soil was taken in 125 ml conical flasks. Then 20 ml of diethylene triamine penta acetic acid (DTPA) extracting solution [(1 l DTPA extracting solution: dissolve 13.1 ml reagent grade triethanolamine (TEA), 1.967 g DTPA (AR grade) and add 1.47 g of CaCl2·2H20 in 100 ml of triple distilled water, pH 7.3 ± 0.5) was shaken for 2 h at 120 cycles min−1 and filtrate was analyzed for Cd using flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Gupta 1993). Samples were taken in triplicate.

Results and discussion

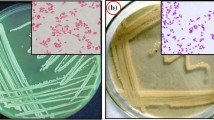

The strains SB32 and SB35 chosen for this study were tolerant to 5 mM CdCl2. Further, psychrotolerant strain SB32 showed optimum growth at 20 °C, while, alkalophilic strain SB35 exhibited optimum growth at pH 9.0. The partial sequencing of 16srDNA of the strains revealed the isolates to be Pseudomonas putida (SB32) and Pseudomonas monteilli (SB35) with accession numbers: HQ610451 and HQ864710, respectively.

Molecular characterization

Cadmium-resistant plasmid and chromosomal operons have also been reported by other workers (Lebrun et al. 1994; Horitsu et al. 1985; Lee et al. 2001; El-Deeb 2009; Mullapudi et al. 2010), therefore, to identify the location of the resistant gene; an attempt was made to amplify the czc gene from both plasmid and genomic DNA of the strains. The plasmid DNA profile revealed the presence of plasmid DNA of ∼5 kb (Fig. 1a). The plasmid DNA isolated from both strains, when subjected to PCR for amplification of the czc gene, produced an amplicon of approximate to 650 bp, whereas no amplicon was obtained in case of genomic DNA in both the strains (Fig. 1b). Also, E.coli DH5α which served as a negative control did not show any amplification. The presence of amplified product from the plasmid DNA of strains SB32 and SB35 indicated the presence of czc gene which is responsible for the efflux of three metal cations, viz. cobalt, zinc and cadmium thereby giving a clear indication of efflux mechanism. The amplicons were sequenced and when compared with the available database using BLASTn search, sequence homology of the cloned genes showed that the amplicons contained a partial czcA gene sequence. The nucleotide sequence of the cloned gene of strains SB32 and SB35 showed 95 % similarity with the czcA gene of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia D457 (accession number HE798556) and 94 % similarity with putative heavy metal efflux pump czcA family of S. maltophilia JV3 (accession number CP002986). Further, alignment of the translated product showed similarity with the heavy metal efflux pump, czcA family of S. maltophilia R551, Stenotrophomonas sp. SKA14 and Acidovorax delafieldii 2AN, thereby indicating the presence of an plasmid-mediated efflux mechanism of resistance in the strains. The czc gene sequences of strains SB32 and SB35 were deposited in gene bank database under accession numbers: KC750207 and KC750208, respectively. The mechanism was further confirmed by AAS and TEM analysis.

a Plasmid DNA profile of cadmium-resistant strains. Lane M λ DNA/EcoR1/HindIII double digest; lanes 1–4 cadmium-resistant strains grown in the absence and presence of CdCl2; 1, 2 SB32; 3, 4 SB35. b Amplified czc gene from plasmid and genomic DNA of cadmium-resistant strains. Lane M 100 bp ladder; lanes 1, 3 amplified czc gene from plasmid DNA of strains SB32 and SB35, respectively; lanes 2, 4 amplified czc gene from genomic DNA of strains SB32 and SB35, respectively

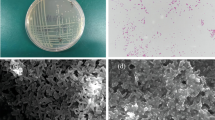

Atomic absorption spectroscopy and transmission electron microscopy

AAS analysis of strain SB32 and SB35 showed that the concentration of Cd in strain SB32, increased in the bacterial cells with the start of log phase (12 h) and reached a maximum of 7.5 μg mL−1 of dry weight of the cell. However, in the supernatant, the concentration of Cd followed was reversed, i.e., the Cd concentration decreased with the start of log phase (Fig. 2a).

Further, in strain SB35, the AAS results showed that the concentration of Cadmium increased with the start of log phase (12 h) and reached to a maximum of 8 μg ml−1 of the dry weight and then decreased after 12 h, i.e., with the end of log phase. However, in the supernatant the concentration of cadmium followed the reverse trend, i.e., the concentration decreased with the start of log phase followed by an increase in the late log phase (Fig. 2b). This clearly indicates the Cd uptake/bioremediation ability of both Pseudomonas strains SB32 and SB35. Furthermore, the AAS data were substantiated by TEM.

TEM analysis revealed an increase in cell size of both strains in the presence of Cd (Fig. 3). Cell length was found increased by 51.13 % in SB32, while, in SB35 the increase was of 25.2 %, although there was no change in cell width. It has been reported previously that SEM analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain MCCB 102 showed an increase in cell size due to Cd together with lead accumulation in the cell wall and along the external cell surfaces (Zolgharnein et al. 2010). However, in this study, the cell length of strain SB32 and SB35 increased due to the entry of metal, but no further deformations were observed. This may be due to the presence of the czc gene which is responsible for the efflux of metal ions from the cells. The metal, which is taken into the cells by fast and unspecific transport for Mg2+ ions, is actively extruded by products of czc resistance determinants (Nies 2000). The ability of a bioinoculant to colonize aggressively makes them the preferred choice for bioremediation studies. Considerable information is available with respect to their use in natural environment but little is known about the effect of pH on bacterial survival, persistence and its subsequent effect on their bioremediation ability. So considering this point, in situ study was conducted with these diversified extremophilic Cd-resistant strains to establish a relationship between pH, temperature, their survival and subsequent effect on soybean growth.

Impact of bioinoculants on Cd toxicity in soybean

After 60 days of germination, the plants were harvested and comparative cadmium accumulation in roots and shoots was measured. Both of the strains were compared for their ability to inhibit cadmium accumulation in plants. Cd toxicity caused a significant reduction in shoot length, root length, fresh and dry weight of soybean, and the magnitude of reduction was 5.0, 30.2, 15.45 and 25.6 % relative to control, respectively (Table 1). Nevertheless, bioinoculation of strains (SB32 and SB35) in Cd-polluted soil increased the agronomical parameters in comparison with uninoculated soil. Such comparison revealed that P. monteilli SB35 strain was able to reduce cadmium accumulation more than P. putida SB32 strain (Table 1) and reduction was found to be 47.5 and 56.9 % by P. monteilli SB35, than 26.9 and 17.6 % by P. putida SB32 in root and shoot, respectively (Fig. 4a). While comparing the effects of the P. putida SB32 and P. monteilli SB35 on the Cd content reduction in soil (Table 1), it appeared that the strain SB35 was more effective in reducing Cd concentration than SB32 and it reduces 1.33 times more than latter in alkaline soil type (Fig. 4b). As evident from the data (Table 1), in alkaline soil, P. monteilli SB35 was found to be more efficient in enhancing plant growth than P. putida SB32 strain. Cadmium mainly occurs as the free metal ion Cd2+ (Bingham and Page 1975) and ion exchange mechanisms have a dominating influence on metal concentration in soil solution. Changes in pH exert both a biological and chemical effect on metal ion toxicity (Campbell and Stokes 1985). Low pH favors greater metal ion solubility, and, in the absence of complexing ions, reduced speciation of the metal ion, which tends to increase toxicity compared to higher pH. However, low pH also enhances competition between H+ and metal ion for cell surface binding sites, which tends to decrease metal ion toxicity.

The increase in agronomical parameters in the presence of cadmium in the soil documented the growth promotory as well as bioremediation potential of bioinoculants. Similar observations were made earlier by Burd et al. (2000). However, toxicity of these metals depends on the soil pH. Further, cadmium content analysis revealed alkalophilic P. monteilli SB35 was more effective than P. putida SB32 strain. Both of the strains were able to reduce the cadmium accumulation in plants and soil significantly. This shows the importance of abiotic factor such as pH for survival and growth of bioinoculants for the establishment of a threshold population of viable inoculant which is an important prerequisite for the successful bioremediation strategy.

Conclusion

It is clear from the above results that resistance to Cd in both the diversified extremophilic strains SB32 and SB35 of Pseudomonas is due to the czc gene present on the plasmid DNA and involves metal binding and/or an efflux mechanism of resistance. Furthermore, the results of in situ trial, AAS, TEM and EDAX analysis suggest that the strains may have considerable potential as an agent for bioremediation under natural conditions with reference to Cd. Moreover, knowledge of the gene employed and the mechanism involved in Cd resistance may be used to design a tailor-made plant growth promotory bioinoculant.

References

Alloway BJ (1990) Cadmium. In: Alloway BJ (ed) Heavy metals in soils. Wiley, New York, pp 100–124

Anderson DG, Mckay LL (1983) Simple and rapid method for isolating large plasmid DNA from Lactic streptococci. Appl Environ Microbiol 46:549–552

Bingham FT, Page AL (1975) In: Hutchinson TC (ed) International conference on heavy metals in the environment, Toronto, pp 433–441

Burd GI, Dixon GD, Glick BR (2000) A plant growth promoting bacterium that decreases heavy metal toxicity in plants. Can J Microbiol 46:237–245

Burke BE, Pfister RM (1986) Cadmium transport by a Cd2+ sensitive and a Cd2+ resistant strain of Bacillus subtilis. Can J Microbiol 32:539–542

Campbell PGC, Stokes PM (1985) Acidification and toxicity of metals to aquatic biota. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 42:2034–2049

Chaoui A, Mazhouri S, Ghorbal MH, Ferjani EE (1997) Cadmium and zinc induction of lipid peroxidation and effects of antioxidant enzyme activities in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Plant Sci 127:139–147

Clausen CA (2000) Isolating metal-tolerant bacteria capable of removing copper, chromium, and arsenic from treated wood. Waste Manag Res 18:264–268

El-Deeb B (2009) Plasmid mediated tolerance and removal of heavy metals by Enterobacter sp. Am J Biochem Biotechnol 5(1):47–53

Goldberg M, Pribyl T, Jhunke S, Nies DH (1999) Energetics and topology of CzcA, a cation/proton antiporter of the RND protein family. J Biol Chem 274:26065–26070

Gupta VK (1993) Soil analysis for available micro-nutrients. In: Tandon HLS (ed) Methods of analysis of soils, plants, waters and fertilizers. Fertilize Development and Consultation Organization, New Delhi, India, pp 26–46

He M, Li X, Liu H, Miller SJ, Wang G, Rensing C (2011) Characterization and genomic analysis of a highly chromate resistant and reducing bacterial strain Lysinibacillusfusiformis ZC1. J Hazard Mater 185:682–688

Horitsu H, Yamamoto K, Wachi S, Kawai K, Fukuchi A (1985) Plasmid-determined cadmium resistance in Pseudomonas putida GAM-1 isolated from soil. J Bacteriol 165(1):334–335

Lebrun M, Audurier A, Cossart P (1994) Plasmid-borne cadmium resistance genes in Listeria monocytogenes are similar to CadA and CadC of Staphylococcus aureus and are induced by cadmium. J Bacteriol 176(10):3040–3048

Lee SW, Glickman E, Cooksey DA (2001) Chromosomal locus for cadmium resistance in Pseudomonas putida consisting of a cadmium-transporting ATPase and a MerR family response regulator. Appl Environ Microbiol 67(4):1437–1444

Mullapudi S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S (2010) Diverse cadmium resistance determinants in Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the Turkey processing plant environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 76(2):627–630

Naidu R, Kookana RS, Sumner ME, Harter RD, Tiller KG (1997) Cadmium sorption and transport in variable charge soils: a review. J Environ Qual 26:602–617

Nies DH (2000) Heavy metal-resistant bacteria as extremphiles:molecular physiology and biotechnological use of Ralstonia sp. CH34. Extremophiles 4:77–82

Nies DH (2003) Eflux-mediated heavy metal resistance in prokaryotes. FEMES Microbiol Rev 27:313–339

Nies DH, Silver S (1995) Ion efflux systems involved in bacterial metal resistances. J Ind Microbiol 14:186–199

Nies DH, Nies A, Chu L, Silver S (1989a) Expression and nucleotide sequence of a plasmid determined divalent cation efflux system from Alcaligenes eutrophus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:7351–7355

Nies A, Nies DH, Silver S (1989b) Cloning and expression of plasmid genes encoding resistance to chromate and cobalt in Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34. J Bacteriol 171:5065–5070

Piqueras A, Olmos E, Martinez-solano JR, Hellin E (1999) Cd induced oxidative burst in tobacco BY2 cells: time course, subcellular location and antioxidant response. Free Radic Res 31:S33–S38

Roane TM, Josephon KL, Pepper IL (2001) Dual-bioaugumentation strategy to enhance remediation of co-contaminated soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:3208–3215

Robinson NJ, Gupta A, Fordham-Skelton AP, Croy RRD, Whitton BA, Huckle JW (1990) Prokaryotic metallothionein gene characterization and expression: chromosome crawling by ligation-mediated PCR. Proc R Soc Lond B 242:241–247

Romero-Puertas MC, McCarthy I, Sandalio LM, Palma IM, Corpas FI, Gomez M, Del Rio LA (1999) Cadmium toxicity and oxidative metabolism of pea leaf peroxisomes. Free Radic Res 31:525–531

Sandalio LM, Dalurzo HC, Gomez M, Romero-Puertas MC, Del Rio LA (2001) Cadmium-induced changes in the growth and oxidative metabolism of pea plants. J Exp Bot 52:2115–2126

Sanita Di Toppi L, Gabbrielli R (1999) Response to cadmium in higher plants. Environ Exp Bot 41:105–130

Silver S (1996) Bacterial resistances to toxic metal ions - a review. Gene 179:9–19

Somashekaraiah BV, Padmaja K, Prasad ARK (1992) Phytotoxicity of cadmium ions on germinating seedling of mungbean (Phaseolus vulgaris): involvement of lipid peroxides in chlorophyll degradation. Physiol Plant 85:85–89

Tsai KJ, Linet AL (1993) Formation of a phosphorylated enzyme intermediate by the cadA Cd2+-ATPase. Arch Biochem Biophys 305:267–270

Tseng TT, Gratwick KS, Kollman J, Park D, Nies DH, Goffeau A, Saier MHJ (1999) The RND superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 1:107–125

Tu SI, Brovillett JN (1987) Metal ion inhibition of cotton root plasma membrane ATPase. Phytochemistry 26:65–69

Vasudevan P, Padmavarthy V, Tewari N, Dhingra SC (2001) Biosorption of heavy metal ions. J Sci Ind Res 60:112–120

Wagner GJ (1993) Accumulation of cadmium in crop plants and its consequence to human health. Adv Agron 51:173–212

Wuertz S, Mergeay M (1997) The impact of heavy metals on soil microbial communities and their activities. In: Van Elsas JD, Wenington EMH, Trevors JT (eds) Modern soil microbiology. Marcel Decker, NY, pp 1–20

Zolgharnein H, Karami K, Mazaheri Assadi M, Dadolahi Sohrab A (2010) Investigation of heavy metals biosorption on Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain MCCB 102 isolated from the Persian gulf. Asian J Biotechnol 2(2):99–109

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Junior research fellowship to SJ by DBT-India during his tenure at GBPUAT, India.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jain, S., Bhatt, A. Molecular and in situ characterization of cadmium-resistant diversified extremophilic strains of Pseudomonas for their bioremediation potential. 3 Biotech 4, 297–304 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-013-0155-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-013-0155-z