Abstract

This contribution investigates the effects of seawater and colloidal silica (NS) in the amounts of 1, 3 and 5 wt%, respectively, on the hydration, strength development and microstructural properties of Portland cement pastes. The data reveal that seawater has an accelerating effect on cement hydration and thus a significant contribution to early strength development was observed. The beneficial effect of seawater was reflected in an improvement in compressive strength for up to 14 days of hydration, while in the 28 days compressive strength values were comparable to that of cement pastes produced with demineralized water. The combination of seawater and NS significantly promotes cement hydration kinetics due to a synergistic effect, resulting in higher calcium hydroxide (CH) production. NS can thus react with the available CH through the pozzolanic reaction and produce more calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel. A noticeable improvement of strength development, as the result of the synergistic effect of NS and seawater, was therefore observed. In addition, mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) tests confirmed significant improvements in microstructure when NS and seawater were combined, resulting in the production of a more compact and dense hardened paste structure. The optimal amount of NS to be mixed with seawater, was found to be 3 wt% of cement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incorporation of admixtures and additives to cementitious formulations enables the production of sustainable cement-based composites, by reducing cement consumption on the one hand and improving certain properties, especially the durability of composites, on the other. In the last two decades the incorporation of nanomaterials (NMs), mainly as cement admixtures, for improving the mechanical and durability properties of cement-based composites in construction, has gathered noticeable attention of researchers and industry. Much attention has especially been paid to the incorporation of silica (SiO2) nanoparticles, with some commercial products already available on the market. It has been reported that nanosilica (NS) have a significant impact on accelerating the hydration process of cement (Singh et al. 2011; Land and Stephan 2012; Skoczylas and Rucińska 2018a), refining the pore structure of cement matrices (Sikora et al. 2016), improving early and long-term mechanical properties (Skoczylas and Rucińska 2018b), as well as improving the durability performance of cementitious composites (Du et al. 2014; Heikal et al. 2016; Marushchak et al. 2017). The beneficial effect of silica nanoparticles is attributable to three synergistic effects: (i) the filler effect—nanosized silica particles fill the voids in the cement matrix, decreasing paste porosity and optimizing the distribution of the pore structure; (ii) the nucleation effect—ultrafine silica nanoparticles act as the nucleation sites (kernels) for the hydration reaction of the cement; (iii) the pozzolanic effect—through the reaction of silica nanoparticles with calcium hydroxide (CH), the amount of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel increases (Singh et al. 2011, 2013; Abd El-Aleem and Ragab 2014; El-Didamony et al. 2016; Маrushchak et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2016; Rupasinghe et al. 2017). The effects of NS on the properties of cement-based composites have been investigated in detail in recent years and many review papers are available (Singh et al. 2013; Safiuddin et al. 2014; Aggarwal et al. 2015; Silvestre et al. 2015; Shah et al. 2015; Bastos et al. 2016; Sikora et al. 2018).

The amount of cement produced in 2016 reached 4.20 billion tonnes (Xiao et al. 2017), which corresponds to around 25 billion tonnes in estimated concrete production and, moreover, production is growing rapidly year by year. This translates directly to the amount of freshwater required to produce the concrete and represents a serious environmental threat in many parts of the world, where the availability of freshwater is a scarce resource (Etxeberria et al. 2016a). The search for alternative sources of water has therefore gathered the noticeable attention of researchers and authorities. While reusing recycled water from concrete production has already been widely established, there is still no agreement regarding how to efficiently use seawater to develop durable and strong concrete (Xiao et al. 2017). However, desalination is highly energy consuming, making desalted water relatively expensive. The use of raw seawater would therefore be a good solution, especially due to the fact that concrete, as the most produced man-made material in the world, has a high potential for incorporating great amounts of seawater, thus saving huge amount of freshwater.

It is widely agreed that the chemical composition of water can interfere with the setting of cement and might have an adverse effect on its strength and durability (Kucche et al. 2015). Various standards, such as ASTM C1602 or EN 1008, therefore give strict guidelines regarding the properties of water which can be used for concrete production. According to EN 1008, salt water can be used for concrete without reinforcement or other embedded metals, but it is generally not suitable for the production of reinforced or prestressed concrete. The maximum chloride content for prestressed concrete or grout; reinforced concrete or embedded metal; concrete without reinforcement or embedded metal should be lower or equal to 500 mg/L, 1000 mg/L, and 4500 mg/L, respectively. The typical chloride content in seawater is around 19,400 mg/L, with Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern seawater exceeding even 21,000 mg/L. As a result, reinforced concrete mixed with seawater will have a high risk of corrosion, induced by the high concentration of chlorides, which is known to be the major cause of steel damage (Bertolini et al. 2002). To overcome these obstacles various solutions have been proposed, including: mixing with pozzolan materials (ground granulated blast furnace slag, fly ash, silica fume), mixing with corrosion inhibitors or replacing conventional reinforcements (made of steel) with corrosion-resistant reinforcement (Otsuki et al. 2012; Lim et al. 2015; Xiao et al. 2017; Tawfik et al. 2018). Furthermore, silica nanoparticles have been introduced as successful admixtures for mitigating the chloride-induced corrosion possibility in concrete (Jalal et al. 2012).

Nevertheless, seawater can be incorporated in various non-reinforced concrete elements, including concrete blocks, pavements or lightweight concretes, where reinforcement is not necessary. The case study undertaken by Etxeberria et al. (2016a) has shown that seawater can be successfully incorporated as a mixing water to produce concrete dyke blocks, while, Chen et al. (2017) have demonstrated the use of seawater in producing fibre-reinforced polymer-confined concrete, as an alternative solution to producing steel-free structures, without the corrosion risk. The life cycle cost analysis undertaken by Younis et al. (2018) has shown that the incorporation of seawater with recycled concrete aggregate along with glass fibre-reinforced polymer (GFRP) rebars, might be a good alternative for the production of structural concrete with improved long-term economic performance.

Several studies have agreed that the salt quantity in seawater can improve the early strength of concrete, with later strength remaining similar or slightly higher in comparison to concrete made with tap water (Demir et al. 2010; Wegian 2010; Otsuki et al. 2012; Abdel-Magid et al. 2016; Etxeberria et al. 2016a). The chloride ion (Cl−) content of seawater contributes to the acceleration of the cement hydration process, thus decreasing the setting time of cement (Govindarajan and Gopalakrishnan 2011) and fastening its hardening (Fernanda et al. 2017). In addition, a decrement in the porosity of the cement matrix and the absorption capacity of concrete have been reported (Etxeberria et al. 2016a; Adiwijaya et al. 2017). Study of Shi et al. (2015) on the synergistic effect of metakaolin (MK) and seawater, has shown that a combination of pozzolanic admixture along with seawater has a noticeable effect on the hydration process and the final mechanical and microstructural properties of concrete. This phenomenon has been attributed to the increased CH content available for pozzolanic reaction with MK, as a result of the reaction of cement with seawater, thus resulting in a higher amount of C-S-H gel formed in the concrete.

Despite the established success of using nanosilica (NS) as admixture in cement-based composites, there has been no study focused on the potential application of seawater as a mixing water for the production of such cement-based composites. As silica nanoparticles are one of the most reactive commercially available pozzolanic materials, their combination with seawater might be a considerable step towards the production of durable and sustainable cementitious composites with significant mechanical performance.

The goal of this study is to therefore evaluate the synergistic effects of commercially available colloidal silica (NS) and seawater, towards the production of sustainable cement-based composites. To characterize the effects of seawater and NS on the cement hydration process, strength development and microstructure cement pastes with different NS contents (1, 3 and 5 wt%) were prepared. Specimens with demineralized water were used as reference samples.

Materials and methods

Materials

The cement pastes were prepared on the basis of Portland cement CEM I 42.5R (conforming to the EN 197-1 standard). Two types of water were used: demineralized (as a reference) and artificial seawater (35.00‰ of salinity), prepared according to ASTM D1141-98. To obtain a reasonable workability for the selected cement pastes, polycarboxylate ether (PCE)-based superplasticizer (BASF ACE430) was used.

Nanomaterial properties and characterization

A commercially available colloidal silica suspension (NS), with a density of 1.4 g/cm3 and containing 20 wt% of solid material, was used. The external (liquid) phase in the NS suspension was further considered to be a part of the mixing water used for the cement paste preparation (see “Cement paste mixture design and specimen preparation”). High-resolution transmission electron microscope (TEM) micrographs are presented in Fig. 1a–c. These clearly show the spherical shape of silica nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 10 to 140 nm. The size distribution of the silica nanospheres is presented in Fig. 1d. The EDX spectrum presented in Fig. 1e shows that the sample was composed of Si and O atoms. The carbon and copper signals present in the spectrum come from the holey carbon TEM grid. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the sample (Fig. 1f), show a single broad peak at around 23° that comes from the amorphous phase of NS. The amorphous phase of NS plays an important role in kinetics of cement hydration, as it is highly advantageous for cementitious reactions (Singh et al. 2011).

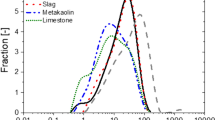

Figure 2 shows the particle size distribution (PSD) of the colloidal silica and cement samples from laser diffraction analyses. Demineralized water and isopropanol were used as dispersants for the NS and cement, respectively. The details of this technique have been described by Hackley et al. (2004). The results of laser granulometry indicated a noticeable difference between the PSD of the cement and of the NS. In the case of the NS, a narrow peak with average particles sizes of 181 nm was detected, while in the cement broad PSD with a D90 value of 43 µm was observed. The results presented in Figs. 1d and 2 illustrate that particle size ranges observed with TEM and laser diffraction methods were slightly different. This inconsistency between the results obtained with different techniques has been widely reported in the literature (Bretsnajdrova et al. 2010; Quercia et al. 2013; Tuoriniemi et al. 2014; Babick 2016). One of the reasons for the difference is associated with the difficulty incompletely breaking particle agglomeration during dispersion in aqueous media (Quercia et al. 2013). Nevertheless, both methods clearly confirmed that NS particles were much finer than the cement particles.

Cement paste mixture design and specimen preparation

Eight types of cement pastes, containing 0, 1, 3 and 5% (by weight of cement) of NS, divided into two groups containing demineralized water (DW) and artificial seawater (SW), were produced. The samples were designated as DW0, DW1, DW3, DW5 and SW0, SW1, SW3, SW5, where the letters indicate the type of water used, while the digits represent the wt% of NS.

The cement pastes were mixed using a mixer conforming to EN 196-1, with a water-to-cement ratio (w/c) equal to 0.5. In order to maintain an equal w/c in all specimens, the mixing water was reduced proportionally to the amount of liquid contained in the NS suspension. The NS was incorporated into the cement paste as an admixture (not exceeding 5 wt%) and as a result the cement content remained fixed in all the cement pastes, in accordance with EN 934-2. Due to the high water absorption of NS particles, specimens containing 5 wt% (DW5 and SW5) required the addition of 0.5 wt% of PCE superplasticizer in order to obtain a reasonable workability. Table 1 presents the compositions of the cement paste mixtures.

The samples were mixed according to the following procedure: 30 s of slow mixing, 1 min of fast mixing, a 1 min break, 1 min of fast mixing. Next, the fresh paste was poured into oiled moulds to form samples with a size of 20 × 20 × 20 mm3. The specimens were cured for 24 h in a climate chamber with a relative humidity of 95% at room temperature (20 ± 1 °C). After 24 h of curing, the specimens were demoulded and cured in the same climate chamber for up to 27 days.

Methods

Isothermal calorimetry

For evaluating the hydration kinetics with calorimetry, 5 g of water was mixed with NS and superplasticizer (if applicable). Next, 10 g of cement was placed in a calibrated plastic container and mixed with 5 g of the suspension. Afterwards, the samples were mixed, and the hydration heat of the samples was measured for a period of 168 h. The heat flow and cumulative heat flow were determined. In addition, for a detailed analysis of the effects of seawater and NS on the hydration kinetics of cement, the acceleration rate of cement hydration was calculated, using the following equation (Eq. 1):

where Hi corresponds to cumulative heat (normalized by cement mass) of the selected sample and Hc corresponds to the cumulative heat (normalized by cement mass) of the DW0 reference paste.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

To study the phase change during the cement hydration process, selected cement pastes were examined with the use of thermogravimetric (TG) analysis. The crushed samples from the hardened cement pastes were taken at 3, 7 and, 28 days and then ground. Isopropanol was used to stop any hydration reactions of the powdered samples and then the samples were well dried. In the TG procedure, the sample was first held at 25 °C for 20 min, and heated from 25 to 1000 °C at 10.00 °C/min.

Afterwards, the mass drop in the thermogravimetric curve at temperatures between 400 and 500 °C, which indicates the loss of water from CH, was calculated. The amount of CH in the specimen was calculated directly from the thermogravimetric curves, using the following equation (Eq. 2):

where WLCH corresponds to the percentage mass loss attributable to CH dehydration and where MWCH and MWH are the molecular weights of CH (74 g/mol) and water (18 g/mol), respectively (Scrivener et al. 2016).

Compressive strength

A compressive strength test of cement pastes was carried out on the 20 × 20 × 20 mm3 cubes after 1, 3, 7, 14 and 28 days of curing, using six samples of each mix. The mean value and standard deviations were taken into consideration.

Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP)

For the characterization of the pore structure, mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) was applied. The MIP method is commonly used to characterize the pore structure in porous materials, due to its simplicity, quickness and wide pore diameter measuring range (Strzałkowski and Garbalińska 2017). In order to obtain information about the pore size distribution of the cement matrix, a MIP test was performed on small-cored samples taken from the specimens. The specimens were immersed in isopropanol after 28 days of curing, to stop hydration and then freeze-dried before testing.

Characterization techniques

The morphology and chemical composition of the NS sample was analysed with a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (TEM) (FEI Tecnai G2 F20 Twin) together with energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy. The crystallographic analysis of the NS sample was conducted on a Philips diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation. Laser diffraction (Malvern Mastersizer 2000, UK) was used to analyse the particle size distribution (PSD) of the colloidal silica and cement samples. The hydration heat of the cement pastes was characterized by isothermal conduction calorimetry with the use of a TAM Air 3 (TA Instruments) calorimeter. TG measurements were performed with the use of a TG 209, Tarsus F3 (Netzsch) instrument under a nitrogen atmosphere, at a flow rate of 250 mL/min. The intrudable pore volume of hardened samples was determined by Pascal 140 and 240 series (Thermo Scientific) mercury intrusion porosimeter. Mercury density was 13.5450 g/mL, surface tension was taken as 0.48 N/m, while the selected contact angle was 140°.

Results and discussion

Hydration kinetics

Variations in the kinetics of the hydration processes of the cement pastes are presented in Fig. 3. In addition, to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the calorimetry study, the acceleration rate of cement hydration, calculated from the cumulative heat (Eq. 1), is presented in Table 2.

A noticeable difference in the hydration kinetics of DW0 and SW0 paste can be observed (Fig. 3a). The replacement of distilled water with seawater accelerated the rate of hydration. The exothermic peak appeared approximately 100 min earlier in SW0, as compared to DW0 and the peak value was ~ 19% higher in comparison to the DW0 paste. The amount of heat released (Table 2) was 19.2% higher after 12 h, in respect to DW0. Furthermore, the disparity between the cumulative heats of the SW0 and DW0 specimens gradually decreased with time. However, even after 3 days of hydration, the released heat value of SW0 was still ~ 7.7% higher. The total cumulative heat values of both specimens were comparable after 7 days of hydration. This confirms the findings in previous works, which have argued that the presence of chloride ions in seawater promotes cement hydration in the early hours. NaCl, MgCl2, CaCl2 have an accelerating effect on cement hydration, especially on calcium silicates (mainly tricalcium silicate—C3S), which results in faster formation of the C-S-H phase and decreases the setting time of the composite (Govindarajan and Gopalakrishnan 2011; Etxeberria et al. 2016b; Fernanda et al. 2017; Parthasarathy et al. 2017).

The introduction of NS resulted in a significant increase in reaction rates, from the very beginning of the hydration process (Fig. 3b). It can be seen that the height of the early rate peak had increased and that the time required to reach the maximum rate was simultaneously reduced. However, the reaction rate was highly dependent on the NS content. In the case of low NS dosages (DW1 and SW1) the exothermic peak was reached only slightly faster by both specimens. In addition, the exothermic peak of DW1 was actually slightly lower as compared to DW0, while in case of SW1 a clear increment in the exothermic peak value was observed, as compared to SW0. After 12 h of hydration (Table 2), the cumulative heat of specimen SW1 was 34% higher than that of the DW0 specimen, while in the case of DW1 only a 3% increment in cumulative heat was reported, as compared with DW0.

The increment in the NS content resulted in a higher hydration rate, which stands in agreement with the literature (Yu et al. 2014), up to a certain amount of NS. As reported by Land and Stephan (2012) and Skoczylas and Rucińska (2018a), the combination of Portland cement and NS causes a considerable increase in hydration heat, due to the nucleation effect of silica nanoparticles, resulting in faster formation of CH and more dynamic consumption of C3S during the binding period. A gradual increment of the exothermic peak was therefore observed, in specimens containing 3 and 5 wt% of NS. It is important to stress that DW5 and SW5 reached the exothermic peak slightly later than the corresponding DW3 and SW3 specimens, due to the presence of PCE superplasticizer, which is widely known to exhibit a retarding effect on cement hydration (Reales and Filho 2017). The highest exothermic peak value was reached by specimen SW5, followed by SW3. However, the SW3 specimen reached the exothermic peak in the shortest time from among all the specimens; 205 min and 104 min faster than in the cases of DW0 and SW0, respectively. After 12 h of hydration, the cumulative heat of SW3 was 44.4% higher than that of the DW0 specimen, while DW3 exhibited an increment of only 17.9%. After up to 7 days of hydration, the cumulated heat released reached comparable values for most mixtures, excluding specimens with a high NS content (DW5 and SW5), where a slight decrease in the cumulative heat value was observed.

Based on the results presented here, it can be concluded that seawater has a noticeable effect on increasing the hydration rate in the early stages of hydration and that this effect is even more pronounced when seawater is mixed with NS. As has been reported by Li et al. (2015) and Parthasarathy et al. (2017), the formation of CH in the early stages is promoted as a result of the acceleration of the hydration process by the chlorides in seawater. CH is therefore consumed at the early stage of hydration, due to the very high pozzolanic activity of NS, resulting in the production of a C-S-H phase. Similar findings have been reported by Shi et al. (2015), where seawater was mixed with metakaolin, another highly reactive pozzolan. To support this conclusion, the evolution of the CH content in specimens with the highest reaction rates, from the DW and SW groups, was analysed with the use of a thermogravimetric technique.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The thermogravimetric curves of the specimens evaluated are presented in Fig. 4a–c, with the quantitative results of CH content calculated according to weight loss and stoichiometric considerations (Eq. 2) depicted in Fig. 4d. The content of CH can reflect the degree of Portland cement hydration (Deboucha et al. 2017). It can be seen that after 3 days of hydration, cement paste made with seawater (SW0) contained more CH than DW0, confirming the accelerating effect of seawater on the hydration of cement (Li et al. 2015). After 7 and 28 days, the CH content in the SW0 specimen remained similar, indicating that most of the hydration had been completed within the first 3 days, while an increment in CH content in the DW0 specimen was observed for up to 28 days. In contrast, the CH content in the pastes containing NS progressively decreased with time, which is in line with other researchers’ observations (Heikal et al. 2013; Abd El-Aleem et al. 2014; Ghafari et al. 2014). In addition, it is evident from these data that the CH content decreased considerably when NS was incorporated into the cement pastes.

As was observed in the previous section, NS can accelerate cement hydration in the first hours of hydration by providing nucleation sites, which means that more CH is produced (Xu et al. 2016). However, after 3 days of hydration the CH content in NS-incorporated specimens was much lower than that of pristine specimens. This is attributable to the fact that amorphous colloidal silica is a highly reactive pozzolanic material, which thus reacts very actively with CH in the pozzolanic reaction in the early ages of cement hydration. As such, more C-S-H gel is generated (Du et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2016). After 3 days of curing, the CH content in DW3 was 16% lower than in the DW0 specimen, while a combination of seawater and NS in specimen SW3 resulted in a CH content 26% lower than in the corresponding SW0 specimen. As has been reported by other researchers (Hou et al. 2013; Abd El-Aleem and Ragab 2015; Xu et al. 2016), although the pozzolanic reaction of NS and cement is usually almost complete after a few days of curing, disparity in the CH content keeps increasing with time, which confirms a slow CH generation and cement hydration of NS-incorporated cement pastes, at a later age. After 28 days of curing the CH content in specimens DW3 and SW3 was lower by 37% and 40%, respectively, in comparison with the corresponding DW0 and SW0.

Compressive strength

Strength development

Figure 5 presents the compressive strength evolution of cement pastes after up to 28 days of curing. Noticeable differences in compressive strength values can be observed from the first day of hydration. After 1 day of hydration, all specimens from the SW group exhibited higher compressive strengths than the corresponding specimens from the DW group. Specimen SW0 exhibited a 41% higher 1-day compressive strength than DW0.

The incorporation of NS contributed to further strength improvements in specimens from the very beginning of the hydration process, confirming both its nucleating and pozzolanic effects, as shown by calorimetry and TGA results; the 1-day strength of specimens SW3 and DW3 was 34.7 MPa and 27.7 MPa (respectively), while specimens SW0 and DW0 exhibited strengths of 23.0 MPa and 16.3 MPa, respectively. However, in the case of low NS dosages (specimens DW1 and SW1), its effect was relatively limited. It is important to stress that all the specimens containing seawater, exhibited over 40% of their final 28-day strength after 1 day of curing, while in the case of the DW group, the specimens exhibited only 30–36% of their final 28-day strength.

The effect of NS was noticeably pronounced after 2 days of curing. The DW3, DW5, SW3 and SW5 specimens exhibited compressive strength values almost double to those of the corresponding DW0 and SW0 specimens. This confirms the high pozzolanic activity of NS in the early days of hydration, which was reflected in our TGA study (“Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)”), showing that NS-modified specimens contained significantly lower CH contents after 3 days of curing (Fig. 4d). Due to the high pozzolanic activity of NS, specimens with higher dosages of NS (3 and 5 wt%) reached over 60% of their final strength, while pristine DW0 and SW0 exhibited only 48.4% and 50.4%, respectively. The compressive strength of the SW3 specimen, after 2 days of curing, was 200% higher than that of the SW0 specimen, while DW3 exhibited a strength 188% higher than that of DW0. In addition, the 2-day compressive strength of the SW3 specimen was equal to and 11% higher, as compared to the SW0 and DW0 specimens’ 28-day strength, respectively. Dynamic strength development was observed for up to 7 days of curing. However, as a result of intensive hydration in the first 2 days, the disparity between the specimens decreased gradually. Nevertheless, after 7 days of curing SW0 exhibited a 23% higher compressive strength than DW0. After 14 days of curing, specimens containing seawater reached almost 100% of 28-day compressive strength (except SW1, which reached 93%), while in case of the DW group, a similar phenomenon was observed only in the case of DW3.

After 28 days of curing, the corresponding specimens of each group exhibited relatively comparable strength values, with only slight variations between them found. Specimen SW3 exhibited the highest strength of 83.5 MPa, while specimens DW0 and SW0 exhibited strengths of 50.8 MPa and 56 MPa, respectively.

Evaluation of the accelerating effects of seawater and NS on compressive strength

To evaluate the synergistic effect of seawater and NS on the strength development of cement pastes, the relative compressive strength values of the samples in relation to the control specimen (DW0) were calculated. The results were calculated for each specimen, as a ratio between the selected specimen’s strength at a certain day of hydration, divided by the strength of the DW0 specimen on the same day of testing. The data are depicted in Fig. 6.

After 1 day of hydration, specimens produced with seawater exhibited more than a 40% higher strength than DW0, while from the second day of hydration the disparity between pristine SW0 and DW0 specimens started to decrease. Nevertheless, SW0 exhibited over a 20% higher strength than DW0 for up to 14 days. This confirms the accelerating effect of cement hydration in the presence of seawater, thus noticeably increasing early strength development. The use of seawater along with NS resulted in significantly increased 1-day strength and a pronounced effect after 2 days. This is attributable to a higher amount of CH produced in SW specimens, meaning that more C-S-H gel could be produced as a result of the pozzolanic activity of NS. After 7 days of curing, the synergistic effect of NS and seawater decreased gradually up to 28 days, at which point specimens with the same NS contents, irrespective of the type of water, exhibited relatively comparable strength values. The incorporation of NS is beneficial in improving the early strength of cement pastes, as well as 28-day strength. However, when a low dosage of NS is incorporated the effect is less pronounced, as was the case in the DW1 and SW1 specimens. When the amount of NS is optimal, significant strength improvement can be observed, as in case of the DW3 and SW3 specimens. Specimens SW3 and DW3 exhibited, respectively, 64% and 52% higher compressive strength values than the DW0 specimen, after 28 days of curing. However, when the amount of NS exceeds the optimum amount, the effect of NS can decrease or be neutralized, as was observed in specimens DW5 and SW5 and as has been reported in the studies of other researchers (Abd El-Aleem et al. 2014; Yu et al. 2014; Abdel Gawwad et al. 2017; Rupasinghe et al. 2017). Thus, to fully benefit from the combination of seawater and NS, the incorporation of an optimal amount of silica seems to be a crucial issue.

Pore size distribution

The obtained pore size distribution plot, covering the pore size range from around 100 µm down to 7 nm, is shown in Fig. 7, while values of total porosity, average and median diameter are summarized in Table 3.

Generally, pore size distribution can be divided into three main size ranges (Aligizaki 2006): mesopores (5–50 nm), middle capillary pores (50–100 nm) and larger capillary pores (> 100 nm). It can be clearly seen that the replacement of demineralized water with seawater has a beneficial effect on decreasing the porosity of cement paste after 28 days of curing. Total porosity of SW0 was decreased by 12% in comparison with DW0. In addition, noticeable refinement of the pore structure was observed. Both average and median pore diameter were decreased in SW0 while compared to DW0 (Table 3). In addition, specimen SW0 contained less amount of large capillary pores than DW0 specimen. As stated by Neville (2006) this critical interval (middle and large capillary pores) is mostly responsible for permeability and penetration of harmful substances into concrete. These observations are in line with studies of previous researchers showing that the use of seawater contributes to decrease the total porosity and refinement of cement matrix (Shi et al. 2015; Adiwijaya et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2018). According to Wang et al. (2018), this effect is attributed to a faster formation of C-S-H phases in the presence of seawater. Authors reported that seawater encourages the formation of high-surface-area C-S-H matrix phases in comparison with tap water, thus more C-S-H matrix phases containing much higher volume fractions of fine C-S-H gel are developed. Results of our MIP tests are in line with results of compressive strength (“Compressive strength”) where SW0 exhibited slightly higher compressive strength value than DW0 after 28 days of curing.

The introduction of NS resulted in a significant decrease of porosity of cement pastes. Incorporation of NS has clearly decreased the total porosity of cement pastes as well as noticeably decreased the average and median diameter of pores (Table 3). It can be observed that by addition of NS, the volume of capillary pores in specimens DW3 and SW3 decreased and the pore structure is more refined than in case of corresponding pristine pastes. This effect is attributed both to nano-filling effect as well as higher amount of C-S-H phase produced due to pozzolanic activity in the cement paste, thus more refined and compacted microstructure was produced. This effect is clearly reflected in the mechanical performance of specimens DW3 and SW3 after 28 days of curing (“Compressive strength”). However, the combination of NS and seawater was more beneficial for refining the microstructure of cement paste than mixture of NS and demineralized water. The total porosity of SW3 was decreased by 33% in comparison with SW0, while DW3 exhibited only 26% decrement of total porosity in comparison with DW0. It is important to stress that mixture of seawater and NS enabled to produce cement paste with 41% lower total porosity than reference DW0 specimen.

Conclusions

This work has evaluated the effects of colloidal silica (NS), in the amounts of 1, 3 and 5 wt% and the use of seawater as a mixing water in the hydration process, on the strength development and microstructural properties of Portland cement pastes. Based on the experimental results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

Seawater has an accelerating effect on Portland cement hydration and thus increases the CH content in the early ages of cement hydration. However, the cumulative heat released after 7 days of hydration is comparable to that of cement mixed with demineralized water.

-

The use of seawater has a noticeable effect on the early strength development of cement paste for up to 14 days of hydration. After 28 days of curing, only a slight strength increment is observed when compared with cement paste made with distilled water.

-

Due to the nucleating effect and the high pozzolanic activity of NS, an acceleration of cement hydration kinetics, along with a significant reduction in CH content from early ages up to 28 days, were observed.

-

The incorporation of NS has a significant effect on accelerating the strength development of cement pastes from the first day of the hydration process. Therefore, cement pastes produced with higher dosages of NS (3 and 5 wt%) exhibited noticeably increased compressive strengths, after up to 28 days of curing, as compared with plain cement pastes.

-

A combination of seawater and NS noticeably increases hydration process kinetics and promotes the pozzolanic reaction. Due to an increased content of CH available for pozzolanic reaction with NS, in cement pastes containing seawater, more C-S-H gel is formed; thus such cement pastes exhibit higher hydration rates and mechanical performance than pastes prepared with deionized water and NS.

-

The use of seawater has a distinct effect on decrement of total porosity and refinement of the pore structure of cement paste. Incorporation of NS optimizes the pore structures and leads to further decrement of total porosity of cement pastes. MIP studies confirmed that the beneficial effect of NS is more pronounced in cement pastes mixed with seawater, hence cement pastes produced with NS and seawater exhibited the lowest values of total porosity, average and median pore diameter.

-

However, the incorporation of an optimal dosage is crucial to fully benefit from mixing seawater and NS. In this study, 3 wt% of NS was established to be an optimal dosage of admixture for producing cement pastes with the best performance.

References

Abd El-Aleem S, Ragab AER (2014) Physico-mechanical properties and microstructure of blended cement incorporating nano-silica. Int J Eng Res Tech 3(7):339–358

Abd El-Aleem S, Ragab AER (2015) Chemical and physico-mechanical properties of composite cements containing micro- and nano-silica. Int J Civ Eng Tech 6(5):45–64

Abd El-Aleem S, Heikal M, Moris WM (2014) Hydration characteristic, thermal expansion and microstructure of cement containing nano-silica. Constr Build Mater 59:151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.02.039

Abdel Gawwad HA, Abd El-Aleem S, Faried AS (2017) Influence of nano-silica and -metakaolin on the hydration characteristics and microstructure of air-cooled slag blended cement mortar. Geosyst Eng 20(5):276–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/12269328.2017.1323678

Abdel-Magid TI et al (2016) Influence of seawater in strengths of concrete mix design when used in mixing and curing. Key Eng Mater 711:382–389. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.711.382

Adiwijaya HH, Sagawa Y, Yamamoto D (2017) Influence of seawater mixing and curing on strength characteristics and porosity of ground granulated blast-furnace slag concrete. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 271:012070 https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/271/1/012070

Aggarwal P, Singh RP, Aggarwal Y, Hussain RR (2015) Use of nano-silica in cement based materials—a review. Cog Eng 2:127. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2015.1078018

Aligizaki KK (2006) Pore structure of cement-based materials: testing, interpretation and requirements. Taylor & Francis, London

Babick F (2016) Suspensions of colloidal particles and aggregates. Springer International Publishing, Cham

Bastos G, Patiño-Barbeito F, Patiño-Cambeiro F, Armesto J (2016) Nano-inclusions applied in cement-matrix composites: a review. Materials 9:1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9121015

Bertolini L, Gastaldi M, Pedeferri MP, Redaelli E (2002) Prevention of steel corrosion in concrete exposed to seawater with submerged sacrificial anodes. Corr Sci 44(7):1497–1513. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-938X(01)00168-8

Bretsnajdrova E, Svoboda L, Zelenka J (2010) Determination of particle shape and size distribution of model types of nanomaterials. J Electr Eng 61(5):302–304

Chen GM, He ZB, Jiang T, Chen JF, Teng JG (2017) Effects of seawater and sea-sand on the behaviour of FRP-confined concrete. In: APFIS2017–6th Asia-Pacific conference on FRP in structures, 19–21 July 2017, Singapore

Deboucha W, Leklou N, Khelidj A, Oudjit MN (2017) Hydration development of mineral additives blended cement using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA): methodology of calculating the degree of hydration. Constr Build Mater 146:687–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.132

Demir Y, Yaprak H, Simsek O (2010) The effect of sea water on the properties of concrete with silica fume admixture. Cement Wapno Beton 1:22–30

Du H, Du S, Liu X (2014) Durability performances of concrete with nano-silica. Constr Build Mater 73:705–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.10.014

El-Didamony H, Abd El-Aleem S, Ragab AER (2016) Hydration behavior of composite cement containing fly ash and nanosized-SiO2. Am J Nano Res Appl 4(2):6–16. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.nano.20160402.11

Etxeberria M, Fernandez JM, Limeira J (2016a) Secondary aggregates and seawater employment for sustainable concrete dyke blocks production: case study. Constr Build Mater 113:586–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.097

Etxeberria M, Gonzalez-Corominas A, Pardo P (2016b) Influence of seawater and blast furnace cement employment on recycled aggregate concretes’ properties. Constr Build Mater 115:496–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.04.064

Fernanda RL, Goncalves JP, Dweck J, da Cunha ALC (2017) Evaluation of influence of salt in the cement hydration to oil wells. Mater Res 20(2):7430747. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5373-MR-2017-0049

Ghafari E, Costa H, Júlio E, Portugal A, Durães L (2014) The effect of nanosilica addition on flowability, strength and transport properties of ultra high performance concrete. Mater Des 59:1–9

Govindarajan D, Gopalakrishnan R (2011) Spectroscopic studies on indian portland cement hydrated with distilled water and sea water. Front Sci 1(1):21–27. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.fs.20110101.04

Hackley VA, Lum LS, Gintaudas V, Ferraris CF (2004) Particle size analysis by laser diffraction spectrometry: application to cementitious powders. NIST IR 7097:1–66

Heikal M, Abd-El Aleem S, Morsi WM (2013) Characteristics of blended cements containing nano-silica. HBRC J 9(3):243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbrcj.2013.09.001

Heikal M, Abd-El Aleem S, Morsi WM (2016) Durability of composite cements containing granulated blast-furnace slag and silica nano-particles. Indian J Eng Mater Sci 23(1):88–100

Hou P, Kawashima S, Kong D, Corr DJ, Qian J, Shah SP (2013) Modification effects of colloidal nanoSiO2 on cement hydration and its gel property. Compos Part B 45:440–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.05.056

Jalal M, Pouladkhan AR, Norouzi H, Choubdar G (2012) Chloride penetration, water absorption and electrical resistivity of high performance concrete containing nano silica and silica fume. J Am Sci 8(4):278–284. https://doi.org/10.7537/marsjas080412.36

Kucche KJ, Jamkar SS, Sadgir A (2015) Quality of water for making concrete: a review of literature. Int J Sci Res Publ 5(1):1–10

Land G, Stephan D (2012) The influence of nano-silica on the hydration of ordinary Portland cement. J Mater Sci 47(2):1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-011-5881-1

Li Q, Geng H, Shui Z, Huang Y (2015) Effect of metakaolin addition and seawater mixing on the properties and hydration of concrete. Appl Clay Sci 115:51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2015.06.043

Lim ED, Roxas CL, Gallardo R, Nishida T, Otsuki N (2015) Strength and corrosion behavior of mortar mixed and/or cured with seawater with various fly ash replacement ratios. Asian J Civ Eng 16(6):835–849

Marushchak U, Sanytsky M, Olevych Y (2017) Effects of elevated temperatures on the properties of nanomodified rapid hardening concretes. MATEC Web Conf P 116:01008. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201711601008

Mаrushchak U, Sanytsky M, Mazurak T, Olevych Y (2016) Research of nanomodified Portland cement compositions with high early age strength. Eastern-Eur J Enterprise Tech 6(84):50–57. https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2016.84175

Neville AM (2006) Properties of concrete, 4th edn. Prentice Hall/Pearson, Harlow

Otsuki N, Saito T, Tadokoro Y (2012) Possibility of seawater as mixing water in concrete. J Civ Eng Arch 10:1273–1279. https://doi.org/10.17265/1934-7359/2012.10.002

Parthasarathy P, Hanif A, Shao H, Li Z (2017) Microstructural and morphological studies of ordinary portland cement paste and fly ash based geopolymer in the presence of chloride ions. In: 71st RILEM annual week & ICACMS 2017, Chennai, India, 3rd–8th September 2017

Quercia G, Lazaro A, Geus JW, Brouwers HJH (2013) Characterization of morphology and texture of several amorphous nano-silica particles used in concrete. Cem Concr Compos 44:77–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.05.006

Reales OAM, Filho RDT (2017) A review on the chemical, mechanical and microstructural characterization of carbon nanotubes-cement based composites. Constr Build Mater 154:697–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.07.232

Rupasinghe M, San Nicolas R, Mendis P, Sofi M, Ngo T (2017) Investigation of strength and hydration characteristics in nano-silica incorporated cement paste. Cem Concr Compos 80:17–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.02.011

Safiuddin M, Gonzalez M, Cao J, Tighe SL (2014) State-of-the-art report on use of nano-materials in concrete. Int J Pavement Eng 15:940–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/10298436.2014.893327

Scrivener K, Snellings R, Lothenbach B (2016) A practical guide to microstructural analysis of cementitious materials. Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton

Shah SP, Hou P, Konsta-Gdoutos MS (2015) Nano-modification of cementitious material: Toward a stronger and durable concrete. J Sustain Cem Based Mater 5:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650373.2015.1086286

Shi Z, Shui Z, Li Q, Geng H (2015) Combined effect of metakaolin and sea water on performance and microstructures of concrete. Constr Build Mater 74:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.10.023

Sikora P, Augustyniak A, Cendrowski K, Horszczaruk E, Rucinska T, Nawrotek P, Mijowska E (2016) Characterization of mechanical and bactericidal properties of cement mortars containing waste glass aggregate and nanomaterials. Materials 9(8):701. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9080701

Sikora P, Abd Elrahman M, Stephan D (2018) The influence of nanomaterials on the thermal resistance of cement-based composites—a review. Nanomaterials 8(7):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8070465

Silvestre J, Silvestre N, de Brito J (2015) Review on concrete nanotechnology. Eur J Environ Civ Eng 20:455–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2015.1042070

Singh LP, Bhattacharyya SK, Mishra G, Ahalawat S (2011) Functional role of cationic surfactant to control the nano size of silica powder. Appl Nanosci 1:117–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-011-0016-1

Singh LP, Karade SR, Bhattacharyya SK, Yousuf MM, Ahalawat S (2013) Beneficial role of nanosilica in cement based materials—a review. Constr Build Mater 47:1069–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.05.052

Skoczylas K, Rucińska T (2018a) Strength and durability of cement mortars containing nanosilica and waste glass fine aggregate. Cement Wapno Beton 23(3):206–215

Skoczylas K, Rucińska T (2018b) The effects of waste glass cullets and nanosilica on the long-term properties of cement mortars. E3S Web Conf 49:00102. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20184900102

Strzałkowski J, Garbalińska H (2017) Porosimetric, thermal and strength tests of aerated and nonaerated concretes. IOP Conf Series: Mater Sci Eng 245:032017 https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/245/3/032017

Tawfik TA, El-Yamani MA, Abd El-Aleem S, Gabr AS, Abd El-Hafez GM (2018) Effect of nano-silica and nano-waste material on durability and corrosion rate of steel reinforcement embedded in high-performance concrete. Asian J Civ Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-018-0093-5

Tuoriniemi J et al (2014) Intermethod comparison of the particle size distributions of colloidal silica nanoparticles. Sci Tech Adv Mater 15:035009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1468-6996/15/3/035009

Wang J, Liu E, Li L (2018) Multiscale investigation on hydration mechanisms in seawater OPC paste. Constr Build Mater 191:891–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.10.010

Wegian FM (2010) Effect of seawater for mixing and curing on structural concrete. IES J Part A Civ Struct Eng 3(4):235–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/19373260.2010.521048

Xiao J, Qiang C, Nanni A, Zhang K (2017) Use of sea-sand and seawater in concrete construction: Current status and future opportunities. Constr Build Mater 155:1101–1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.130

Xu Z, Zhou Z, Du P, Cheng X (2016) Effects of nano-silica on hydration properties of tricalcium silicate. Constr Build Mater 125:1169–1177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.09.003

Younis A, Ebead U, Judd S (2018) Life cycle cost analysis of structural concrete using seawater, recycled concrete aggregate, and GFRP reinforcement. Constr Build Mater 175:152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.04.183

Yu R, Spiesz P, Brouwers HJH (2014) Effect of nano-silica on the hydration and microstructure development of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) with a low binder amount. Constr Build Mater 65:140–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.063

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science Centre (Poland) within project No. 2016/21/N/ST8/00095 (PRELUDIUM 11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Submitted to special issue NANO-2018 within the 6th International Conference “Nanotechnologies and Nanomaterials” NANO-2018.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sikora, P., Cendrowski, K., Abd Elrahman, M. et al. The effects of seawater on the hydration, microstructure and strength development of Portland cement pastes incorporating colloidal silica. Appl Nanosci 10, 2627–2638 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-019-00993-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-019-00993-8