Abstract

This work deals with the sensitization of the porous TiO2 films of thickness about 4 µm deposited on fluorine-doped tin oxide with nanocrystalline Bi2S3 for photovoltaic application. The sensitization was achieved for four different sensitization times employing chemical solution deposition with bismuth nitrate and sodium thiosulphate as precursors for Bi3+ and S2−, respectively. The unsensitized and sensitized photoelectrodes were characterized using X-ray diffractometry, scanning electron microscopy and diffused reflectance spectroscopy. XRD patterns show the signatures of both anatase TiO2 and orthorhombic Bi2S3 in the sensitized photoanodes. However, crystallinity of Bi2S3 increased with increase in sensitization time from 10 to 40 min. The temporal effect of sensitization and annealing on the photovoltaic performance of the solar cells fabricated using four different photoelectrodes was studied using the photocurrent density versus photovoltage curves. Annealing apparently improved the photovoltaic performance of photoanodes. The best performance was obtained for cell fabricated using annealed TiO2/Bi2S3 photoanode after 30 min sensitization time showing V oc ~ 0.37 mV, J sc ~ 0.52 mA/cm2, FF ~ 68 and 0.43 %.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, nanostructured semiconductors employing various strategies have apparently shown very promising contribution in solar cell applications as sensitizers (Sun et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2011, 2012; Kieven et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012; Rajendra Prasad et al. 2013; Mane et al. 2014). Semiconductor-sensitized solar cells are excitonic solar cells that are architecturally similar to dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSC) but the difference is that the semiconductor nanocrystals are the light harvesters in the former and it is the dye molecules which absorb light in the latter (Nozik 2008). Semiconductor nanostructures are attractive alternative to the light-harvesting dye molecules in these nanostructured solar cells for a number of reasons including their unique properties like tunable band gap over a wide range to match the solar spectrum, their good photostability, broad excitation spectra besides their high extinction coefficients and capability to result in phenomenon like multiple exciton generation (Kamat 2008). In addition to this, suitability to synthesize the semiconductor nanostructures with different approaches and conditions provides tunability of structural and optical properties of these sensitizers which is not the case in respect of organic dyes. In view of this, nanostructured semiconductor-sensitized heterojunction solar cells of late have received attention of researchers. In general, semiconductors like CdS (Sun et al. 2008), CdSe (Chen et al. 2012), Ag2S (Chen et al. 2011), In2S3 (Kieven et al. 2008) and PbS (Wang et al. 2012) are extensively used as sensitizers for solar cell applications. Results obtained in previous works suggest that for optimal performance in heterojunction solar cells, the sensitizer should have an optical band gap in the range of 1–2.5 eV (Sun et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2011, 2012; Kieven et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012). Therefore, bismuth sulfide (Bi2S3), a group V–VI, direct band gaps semiconducting materials of interest for solar cell application due to its large absorption coefficient and bulk band gap of 1.3 eV (Lokhande et al. 1997). Such ideal combination of properties of this material makes it one of the suitable semiconducting materials for photovoltaic applications as discussed by the Shockley and Queisser in respect of p–n homojunction solar cells (Shockley and Queisser 1961; Cademartiri et al. 2008; Yousefi et al. 2012). Also, the relative positions of the conduction band energy levels of nanostructured Bi2S3 and TiO2, a widely used semiconductor oxide as a photoanode in solar cell applications (Patil et al. 2014), display favorable energetics for electron transformer from the former to the latter (Nayak et al. 1983).

Among the different studies on Bi2S3-based solar cells, many reports are on the thin film-based solar cells (Wang et al. 2007; Moreno-García et al. 2011; Becerra et al. 2011) and photoelectrochemical solar cells (PEC) (Bhattacharya and Pramanik 1982; Mane et al. 2007; Rajalakshmi et al. 2013; Narayanan et al. 2013; Jana et al. 2009; Rath et al. 2011). These days, Bi2S3 has received considerable attention as an absorber in photovoltaic applications (Kamat 2008). However, the reports available on nanocrystalline Bi2S3-sensitized solar cells are limited (Vogel et al. 1994; Suarez et al. 1998), which showed very low power conversion efficiency (PCE) as compared to other nanocrystalline semiconductor-sensitized solar cells (Wang et al. 2013; Santra and Kamat 2012; Yan et al. 2013). In spite of merits of this semiconductor material for its solar cell application, reasons for the low conversion efficiencies of cells based on Bi2S3 still elude better understanding. Studies on different factors responsible for the photoconversion in these cells need to be carried out and optimized for obtaining the theoretically projected efficiencies of these nanostructured excitonic solar cells. The present study considers the effect of sensitization time and annealing on the performance of the Bi2S3-based heterojunction solar cell.

In this study, the porous TiO2 photoelectrodes have been prepared by doctor blade method. Sensitization of TiO2 photoelectrode with nanocrystalline Bi2S3 has been achieved using chemical bath deposition by varying the sensitization time from 10 to 30 min. The effect of sensitization time on photovoltaic parameters of Bi2S3-sensitized TiO2 photoelectrode has been studied systematically.

Experimental

TiO2 photoelectrode preparation

The porous photoelectrode of TiO2 was prepared on previously cleaned FTO (Fluorine-doped tin oxide) by doctor blade method using TiO2 paste. The paste was prepared using TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized with titanium isopropoxide as precursor. The prepared paste was spread evenly onto FTO shielded with spacer tape (Scotch tape) using glass rod resulting in photoelectrodes of nearly same thickness about 4 µm. After drying in the air, these photoelectrodes were annealed at 450 °C for 1 h.

Chemical bath deposition of Bi2S3 on the TiO2 photoelectrode

Chemical bath was prepared for Bi2S3 using mixture of 0.01 M solution of bismuth nitrate [Bi (NO3)3] prepared in 1 M HNO3 and 0.01 M aqueous solution of sodium thiosulphate [Na2S2O3] as precursors for Bi3+ and S2−, respectively (Lokhande et al. 1997). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was used as a complexing agent to control the release of soluble species of Bi3+ in the sensitization bath. Initially, 0.01 M [Bi (NO3)3] was mixed with the 0.2 M aqueous solution of EDTA under constant stirring. The pH of the bath was maintained at about 2 and then an aqueous solution of 0.01 M [Na2S2O3] was added slowly under constant stirring. The prepared TiO2 photoelectrodes were introduced vertically in the bath at room temperature for the purpose of sensitization. Bi2S3 was deposited over TiO2 by decomposition of the Bi(NO3)3 in an acidic medium containing Bi salt complexed with EDTA, which was instrumental in controlling the Bi3+ ion concentration and allowed slow release of species of Bi3+ in acidic medium. The deposition process was considered to be based on this slow release of Bi3+ and S2− ions in the solution which then condensed as ion by ion or cluster by cluster on the surface of substrate that was placed in the solution. It is well known that the deposition of Bi2S3 occurs when the ionic product (IP) of Bi3+ and S2− exceeds the solubility product (Ksp = 10−73) of the Bi2S3 (Lokhande et al. 1997). After completing the desired reaction time of 10, 20, 30 and 40 min, the photoelectrodes were withdrawn from the bath and the corresponding photoanodes were named as P-10, P-20, P-30 and P-40, respectively. The sensitized photoelectrodes were observed to be coated with increasing dark brown layers which may be due to probable deposition of Bi2S3 layer with increasing sensitization time onto the bare photoanodes of TiO2.

Solar cell assembly

For cell assembly, the carbon-coated FTO was used as a counter electrode. The Bi2S3-sensitized TiO2 photoelectrode of area about 0.25 cm2 and counter electrode were clamped together into a sandwich-type configuration with droplet of polysulphide electrolyte injected in between them. The fabricated solar cells using photoelectrodes P-10, P-20, P-30 and P-40 were named C-10, C-20, C-30 and C-40, respectively, and were characterized for their PV performance before and after annealing process.

The analysis of structural, morphological properties and elemental composition was carried out using X-ray diffractometry (XRD) (model: XRD, Rigaku “D/B max-2400”, Cu Kα = 0.154 nm), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (model: JEOL-JSM 6360-A), respectively. A UV–Vis spectrophotometer (model: JASCO V-670) was used to record optical absorption spectra of unsensitized and sensitized photoelectrodes in diffused reflectance mode in the range 200–800 nm at room temperature. The cell performance was measured by a semiconductor characterization unit (Keithley 2420 source meter) under illumination of 30 mW/cm2.

Results and discussion

Structural properties

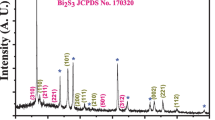

The crystalline structure of the unsensitized TiO2 photoelectrode and photoelectrodes P-10 to P-40 prepared for different deposition times (as prepared and annealed) is characterized with X-ray diffraction (XRD) and shown in Fig. 1a, b. Figure 1a shows diffraction pattern for bare TiO2 photoelectrode with defined peaks at 2θ = 25.33°, 37.80°, 48.26° and 54.69° corresponding to the diffraction from (101), (004), (200) and (105) planes which confirms anatase phase for bare TiO2 (JCPDS file no: 86-1157). However, Fig. 1a (a), the XRD pattern for P-10, does not show the presence of Bi2S3 in addition to anatase phase of TiO2, probably due to the small amount of Bi2S3 compared to TiO2. However, the signature reflections of Bi2S3were identified at 2θ = 33.77° and 51.47° in patterns of P-20, P-30 and P-40, corresponding to the diffraction from (311) and (222) planes as shown in Fig. 1a (b–d) can be indexed to the orthorhombic Bi2S3 (JCPDS file no: 06-0333) besides those of anatase TiO2. Also, it can be clearly inferred from XRD pattern of the photoanodes P-10 to P-40 that showed increase in intensity of the peaks as a result of annealing which may be attributed to the enhanced crystallinity of Bi2S3 as shown in Fig. 1b. The average crystallite size in each film sample was calculated using a standard method in the literature (Kulkarni et al. 2015) after incorporating due corrections for the instrumental and strain-induced broadening in the diffraction peaks. The average crystallite size of Bi2S3 crystals was found to be in the range of 20–54 nm.

Optical properties

The absorption spectra of the unsensitized TiO2 and Bi2S3 sensitized TiO2 photoelectrodes prepared with different sensitization time (P-10, P-20 and P-30) are shown in Fig. 2. It is seen from the figure that the absorption for bare TiO2 is limited to the ultraviolet region of electromagnetic spectrum, whereas for all sensitized photoelectrodes, the absorbance is enhanced in the visible region. It can be noted that the intensity of the absorption spectra grows in the visible region from 400 to 600 nm with the increasing sensitization time for photoelectrodes from P-10 to P-40. This fact suggests that amount of loading of a sensitizer increases with increase of loading time resulting in enhanced absorption of visible light from P-10 to P-40. Also, there is an apparent red shift in the absorption feature from P-10 to P-40, which is probably a consequence of increase in particle size of sensitizer with increase of deposition time and may be attributed to the aggregation of sensitizer on the surface of bare photoelectrode.

Morphological properties and elemental analysis

To further analyze the effect of sensitization time on the TiO2 photoelectrode, morphology of both bare and sensitized photoelectrode was studied. Figure 3 shows the scanning electron micrographs for unsensitized and sensitized TiO2 photoelectrode with different sensitization times. Figure 3 (bare TiO2) shows the porous photoanode of bare TiO2. However, on sensitization with Bi2S3, it is clearly seen from Fig. 3 (P-10 to P-40) that the pores in TiO2 photoelectrode are filled up with nanocrystalline Bi2S3. The pore filling apparently increased with increase of deposition time from P-10 to P-40. In addition to this, there is no observable alteration in the surface quality and structure of the TiO2 photoelectrodes with the increase in sensitization time.

Besides, elemental analysis was carried out by EDS for sensitized photoelectrode with increasing deposition time and compared as shown in Fig. 4. It reveals the presence of Ti, O, Bi and S in all sensitized films. It can be clearly inferred from the intensity of the spectra for different samples that the amount of Bi and S was observed to be continuously increasing with the deposition time. Therefore, the XRD results along with EDS spectrum analysis demonstrate that crystalline nanoparticles were deposited on anatase TiO2 by CBD.

Photovoltaic characterization

Figure 5b shows photocurrent density (J) versus photovoltage (V) characteristics curves of the fabricated solar cells namely, C-10, C-20, C-30 and C-40, respectively. The photovoltaic parameters like short circuit current density (J sc), open circuit voltage (V oc), fill factor (FF) and photovoltaic efficiency (η) are obtained from the J−V curves and the same are listed in Table 1. The overall photovoltaic performance increased from C-10 to C-30 and then dipped for C-40.

With increase of sensitization time, the optical absorption spectra as given in Fig. 3 clearly show an enhanced loading of the sensitizer into the photoelectrodes which is evident from the improved optical absorption in the visible region. Such an enhanced absorption of light in the visible region leads to generation of increased number density of excitons at the electrode–electrolyte interface. The excitons so generated get dissociated at the TiO2–Bi2S3 interface due to the favorable interfacial band energetic (see Fig. 5a) leading to effective electron injection from excited Bi2S3 to the conduction band of TiO2 (Nayak et al. 1983). This further results in improved photocurrent (J) in C-30 and so doubling of J sc.

Besides, J sc, V oc has also improved for the cells from C-10 to C-30 as shown in Table 2. In the standard expression for V oc (Tayagaki and Hoshi 2013), as shown in Eq. (1), enhancement in V oc is possible with either the increase of J sc or the decrease of recombination current J 0 or both.

In the present study, in addition to the higher J sc, the magnitude of J 0 seems to have decreased substantially from C-10 to C-30. As discussed earlier, reduction in J 0 may be correlated from the micrographs shown in Fig. 4 that there is an apparent improvement in the loading of the sensitizer over the surface of the porous titania photoanode from P-10 to P-30. This probably led to relatively better conformal coating of Bi2S3 nanocrystals in P-30 as shown in the schematic (see Fig. 6a). Such a conformal coating leading to a near monolayer adsorption of sensitizer on the titania surface reduces the probable recombination of the conduction band electrons in TiO2 with the redox species in the electrolyte (Lee et al. 2009). The plausible mechanism of electron transfer is depicted in Fig. 6b and c. This may have reduced J 0 giving rise to enhanced photovoltage and so greater V oc in C-30. Such a decrease in recombination current should naturally enhance the shunt resistance. This is evident from the J−V curves shown in Fig. 5b, which resulted in increase in fill factor (FF) from C-10 to C-30 as listed in Table 2, supporting the above argument.

a Schematic presentation showing probable sensitization of bare TiO2 with Bi2S3 for four different sensitization times 10, 20, 30 and 40 min. b Cartoon showing possible recombination of injected electron in conduction band of TiO2 with redox species as an effect of less coverage of surface of TiO2. c Cartoon showing possibility of reduction of recombination of injected electron in conduction band of TiO2 with redox species as an effect of less coverage of surface of TiO2

However, as shown in Fig. 5, C-40 showed a decline in photovoltaic performance. Such a result may be attributed to the aggregation of sensitizer leading to clogging of the TiO2 pores. The apparent red shift in the optical absorption spectra supports such an aggregation. In fact, such a clogging of sensitizer results in decrease of the access of electrolyte into the pores of photoanode increasing the recombination probability in the film (Zhang et al. 2009; Solis et al. 2013). Though, there is enhancement in J sc due to increased sensitizer in the films, the recombination due to aggregation has apparently overpowered this enhancement in J sc leading to the decline in V oc.

On the other hand, it can be observed from Fig. 5c that cells fabricated using annealed photoanodes show apparent enhancement in all cell parameters including photoconversion efficiency. However, the trend observed in the annealed photoanode-based solar cells is the same as that of their unannealed photoanode-based counter parts. The results of the photovoltaic performance are tabulated in Table 2.

Conclusion

In the present report, we have studied the performance of Bi2S3-sensitized titania-based solar cells as a function of sensitization time and annealing of photoanodes. From the study, it may be concluded that there is an optimal sensitization time for the photoanode to obtain the best conversion efficiency beyond which the device performance dips down due to aggregation of sensitizer. Conformal coating of the sensitizer over the surface of the mesoporous photoelectrode, P-30 is attributed for such an enhancement in the solar cell performance. Indeed, such a coating can improve the light-harvesting efficiency besides mitigating the back electron transfer. Also, improved crystallinity in the sensitizer due to annealing of the photoanode resulted in elevated photovoltaic performance in the solar cells based on these photoanodes.

References

Becerra D, Nair MTS, Nair PKJ (2011) Analysis of a bismuth sulfide/silicon junction for building thin film solar cells. Electrochem Soc 158:H741–H749

Bhattacharya RN, Pramanik PJ (1982) Semiconductor liquid junction. Solar cell based on chemically deposited Bi2S3 thin film and some semiconducting properties of bismuth chalcogenides. Electrochemistry 129:332–335

Cademartiri L, Malakooti R, O’Brien PG, Migliori A, Petrov S, Kherani NP, Ozin GA (2008) Large-scale synthesis of ultrathin Bi2S3 necklace nanowires. Angew Chem Int Ed 47:3814–3817

Chen C, Xie Y, Ali G, Yoo SH, Cho SO (2011) Improved conversion efficiency of Ag2S quantum dot-sensitized solar cells based on TiO2 nanotubes with a ZnO recombination barrier layer. Nanoscale Res Lett 6:462–470

Chen YX, Wei L, Zhang GH, Jiao J (2012) Open structure ZnO/CdSe core/shell nanoneedle arrays for solar cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett 7:516–521

Jana A, Bhattacharya C, Sinha S, Datta J (2009) Study of the optimal condition for electroplating of Bi2S3 thin films and their photoelectrochemical characteristics. J. Solid State Electrochem 13:1339–1350

Kamat PV (2008) Quantum dot solar cells. Semiconductor nanocrystals as light harvesters. J Phys Chem C 112:18737–18753

Kieven D, Dittrich T, Belaidi A, Tornow J, Schwarzburg K, Allsop N, Lux-Steiner M (2008) Effect of internal surface area on the performance of ZnO/In2S3/CuSCN solar cells with extremely thin absorber. Appl Phys Lett 92:153107

Kulkarni AN, Arote SA, Pathan HM, Patil RS (2015) Time dependent synthesis of crystalline Bi2S3 and its application as a sensitizer in SnO2 based solar cells. Int J Mat Res 106:314

Lee H, Wang M, Chen P, Gamelian D, Zakeeruddin S, Gratzel M, Nazeeruddin M (2009) Efficient CdSe quantum dot-sensitized solar cells prepared by an improved successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction process. Nano Lett 9:4221–4227

Lokhande CD, Ubale AU, Patil PS (1997) Thickness dependent properties of chemically deposited Bi2S3 thin films. Thin Solid Films 302:1–4

Mane RS, Desai JD, Joo O-S, Han S-H (2007) Surface morphology and optical studies of non-aqueous Bi2S3 thin films. Int J Electrochem Sci 2:141–148

Mane RM, Ghanwat VB, Kondalkar VV, Khot KV, Mane SR, Patil PS, Bhosale PN (2014) Nanocrystalline MoBi2Se5 ternary mixed metal chalcogenide thin-films for solar cell applications. Proced Mat Sci 6:1285–1291

Moreno-García H, Nair MTS, Nair PK (2011) Chemically deposited lead sulfide and bismuth sulfide thin films and Bi2S3/PbS solar cells. Thin Solid Films 519:2287–2295

Narayanan R, Deepa M, Friebel F, Srivastava AK (2013) A CdS/Bi2S3 bilayer and a poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/S2—interface control quantum dot solar cell performance. Electrochem Acta 105:599–611

Nayak BB, Acharya HN, Mitra GB (1983) Structural characterization of Bi2−xSbxS3 films prepared by the dip-dry method. Thin Solid Film 105:17–24

Nozik A (2008) Multiple exciton generation in semiconductor quantum dots. J Chem Phys Lett 457:3–11

Patil PB, Mali SS, Kondalkar VV, Pawar NB, Khot KV, Hong CK, Patil PS, Bhosale PN (2014) Single step hydrothermal synthesis of hierarchical TiO2 microflowers with radially assembled nanorods for enhanced photovoltaic performance. RSC Adv 4:47278–47286

Rajalakshmi PU, Oommen R, Sanjeeviraja C (2013) Improved photoelectrochemical performance of (Bi1−xSbx)2S3 photoanodes. Thin Solid Films 531:76–80

Rajendra Prasad MB, Deena S, Rajesh Ch, Pandit Vishal K, Pathan Habib M (2013) Employing green synthesized silver nanoparticles as light harvesters in nanostructured solar cells. J Ren Sust Energy 5:031615

Rath AK, Bernechea M, Martinez L, Konstantatos G (2011) Solution-processed heterojunction solar cells based on p-type pbs quantum dots and n-type Bi2S3 nanocrystals. Adv Mater 23:3712–3717

Santra PK, Kamat PV (2012) Mn-Doped quantum dot sensitized solar cells. A strategy to boost efficiency over 5 %. J Am Chem Soc 134:2508–2511

Shockley W, Queisser HJ (1961) Detailed balance limit of efficiency of p–n junction solar cells. J Appl Phys 32:510519

Solis M, Rincon M, Calva J, Alvarado G (2013) Bismuth sulfide sensitized TiO2 arrays for photovoltaic applications. Electrochem Acta 112:159–163

Suarez R, Nair PK, Kamat PV (1998) Photoelectrochemical behavior of Bi2S3 nanoclusters and nanostructured thin films. Langmuir 14:3236–3241

Sun W, Yu Y, Pan H, Gao XF, Chen Q, Peng LM (2008) CdS quantum dots sensitized tio2 nanotube-array photoelectrodes. J Am Chem Soc 130:1124–1125

Tayagaki Takeshi, Hoshi Yusuke (2013) NoritakaUsami. Sci Rep 3:2703

Vogel R, Hoyer P, Weller H (1994) Quantum-sized PbS, CdS, Ag2S, Sb2S3 and Bi2S3 particles as sensitizers for various nanoporous wide—bandgap semiconductors. J Phys Chem 98:3183–3188

Wang ZJ, Qu SC, Xu Y, Chen YH, Zeng XB, Liu JP, Wu J, Wang ZG (2007) Solventless synthesis of Bi2S3 nanowires and their application to solar cells. Adv Mater Res 26–28:601607

Wang LD, Zhao DX, Su ZS, Shen DZ (2012) Hybrid polymer/ZnO solar cells sensitized by PbS quantum dots. Nanoscale Res Lett 7:106

Wang J, Mora-Sero I, Pan Z, Zhao K, Zhang H, Feng Y, Yang G, Zhong X, Bisquert J (2013) Core/Shell colloidal quantum dot exciplex states for the development of highly efficient quantum-dot-sensitized solar cells. J Am Chem Soc 135:15913–15922

Yan K, Chen W, Yang S (2013) Significantly enhanced open circuit voltage and fill factor of quantum dot sensitized solar cells by linker seeding chemical bath deposition. J Phys Chem C 117:92–99

Yousefi M, Sabet M, Salavati-Niasari M, Emadi H (2012) Synthesis and characterization PbS and Bi2S3 nanostructures via microwave approach and investigation of their behaviors in solar cell. J Cluster Sci 23:511–525

Zhang Y, Xie TF, Jiang TF, Wei X, Pang S, Wang X, Wang DJ (2009) Surface photovoltage characterization of a ZnO nanowire array/CdS quantum dot heterogeneous film and its application for photovoltaic devices. Nanotechnology 20:155707

Acknowledgments

HMP is thankful to Departmental Research Development Program, Savitribai Phule University Pune, Pune—07 for partial financial support. HMP is also thankful to BCUD, SPPU, Pune for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kulkarni, A.N., Rajendra Prasad, M.B., Pathan, H.M. et al. TiO2 photoanode sensitized with nanocrystalline Bi2S3: the effect of sensitization time and annealing on its photovoltaic performance. Appl Nanosci 6, 567–574 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-015-0458-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-015-0458-y