Abstract

Wellbore instability issues represent the most critical problems in Iraq Southern fields. These problems, such as hole collapse, tight hole and stuck pipe result in tremendous increasing in the nonproductive time (NPT) and well costs. The present study introduced a calibrated three-dimensional mechanical earth model (3DMEM) for the X-field in the South of Iraq. This post-drill model can be used to conduct a comprehensive geomechanical analysis of the trouble zones from Sadi Formation to Zubair Reservoir. A one-dimensional mechanical earth model (1DMEM) was constructed using Well logs, mechanical core tests, pressure measurements, drilling reports, and mud logs. Mohr–Coulomb and Mogi–Coulomb failure criteria determined the possibility of wellbore deformation. Then, the 1DMEMs were interpolated to construct a three-dimensional mechanical earth model (3DMEM). 3DMEM indicated relative heterogeneity in rock properties and field stresses between the southern and northern of the studied field. The shale intervals revealed prone to failure more than others, with a relatively high Poisson's ratio, low Young's modulus, low friction angle, and low rock strength. The best orientation for directional Wells is 140° clockwise from the North. Vertical and slightly inclined Wells (less than 40°) are more stable than the high angle directional Wells. This integration between 1 and 3DMEM enables anticipating the subsurface conditions for the proactive design and drilling of new Wells. However, the geomechanics investigations still have uncertainty due to unavailability of enough calibrating data, especially which related with maximum horizontal stresses magnitudes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the lifetime of the oilfield, various operations and Well construction are affected by the regional stress state. One of these operations is the Well drilling that may create disturbances to the original condition of the stresses forming mechanical instability near the wellbore (Fjar et al. 2008). This wellbore instability may cause extensive drilling problems, adding more cost to the drilling in the exploration and development stages (Mitchell 2001; Zhang 2019). Sophisticated drilling conditions like highly deviated Wells, multilateral Wells, horizontal Wells, depleted reservoirs, and Wells in high tectonic activity make the stability issues more challenging to handle (Abbas et al. 2018). Geomechanics can substantially decrease the stability issues by constructing a comprehensive mechanical earth model (MEM) to predict the state of stress and mechanical rock properties. MEM typically helps to design a stable mud window and orientate the Well to a safe trajectory as possible (Abdulridha et al. 2020). The three dimensional mechanical earth model (3DMEM) predicts the Geomechanical property between Wells which enables fully integrating geomechanics variations in geology, and trajectories in the planning of deviated and horizontal Wells where easy extraction of data along any trajectory (Hughes 2017). In addition, the 3D model provides more accurate and better problem visualization in each horizon for the entire field (Zamora Valcarce et al. 2006). Therefore, a 3DMEM is the best procedure for combining all the accessible information (Abdulridha et al. 2020). Geostatistics is highly demanded to populate the geomechanical parameters in three-dimensional models for long intervals and large areas where simulation needs a dynamic reservoir model, consumes time, and requires computers with high efficiency (Kadyrov and Tutuncu 2012).

Methods

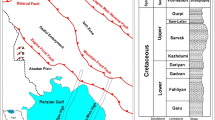

This study presents a methodology to predict the optimized wellbore trajectory with a safe mud window utilizing 1DMEMs of each well and a 3DMEM constructed by interpolating the 1DMEMs. The input logs to build a 1DMEM involve density, compressional and shear slowness, porosity, Gamma-ray, caliper, and Formation Micro imager (FMI). Pore pressure measurements were available for the producing sandstone and limestone reservoirs. The laboratory mechanical measurements on core samples are carried out for the Sadi, Ahmadi, Nahr Umr, and Zubair formations. The dynamic elastic properties are calculated assuming homogeneous, isotropic, and elastic rocks using compression sonic (DTC) and shear sonic (DTS) and density logs (ρb) (Eqs. 1, 2, 3, and 4) (Zoback 2007). The static elastic properties are determined utilizing a correlation between dynamic and static measurements. The angle of internal friction is determined with a linear correlation from Gamma-ray. Gamma-ray of 120 gAPI is assigned to 20° friction angle, and 40 gAPI for 35°. If the friction angle falls outside this range, it is converged to the nearest value. The Static Young's modulus correlation proposed by Dick Plumb (1994) (Plumb 1994) and modified in 2002 is used to determine the unconfined compressive strength (UCS or C0) as in Eq. (5). Tensile strength (TS) is calculated based on a simple correlation with the UCS as in Eq. (6) (Schlumberger 2018).

where G is the dynamic shear modulus, K is the dynamic bulk modulus, Edyn is the dynamic Young's modulus, and νdyn is the dynamic Poisson ratio. FK is a facies and zone-based factor (in this article, it is assumed to be 0.08).

The total overburden stress (σV) is calculated from the bulk density gradient in overlying rocks as shown in Eq. (7) (Aadnoy and Looyeh 2011). Eaton's method utilizing the total vertical stress and acoustic log (Δt) to determine the pore pressure (Pp) of shale zones, Eq. (8) (Eaton 1975). For non-shale zones, the normal pore pressure (Ppn) is calculated by applying the average pore fluid density. For quality assurance, the computed pore pressure profile is compared to the direct measurement in the permeable zones. The poroelastic approach presents an effective method to determine the total horizontal stresses using Eqs. (9) and (10) (Higgins et al. 2008). FMI and four-arm caliper log are utilized to determine the horizontal stresses orientations based on breakouts failure directions.

where "g" is the gravity acceleration, "h" is the vertical thickness of the rock formation, Δtn is the slowness in shales at normal pressure, and Δt is the slowness from the sonic log, "a" and "n" are fitting parameters named Eaton factor and Eaton exponent respectively, α is the Biot coefficient, E is the static Young's modulus, and ν is the static Poisson ratio.

The failure criteria consider the stress concentration around the borehole to identify the stress values at which wellbore failure may occur (Matanovic et al. 2012; Manshad et al. 2014). Wellbore stability analysis typically determines a safe drilling mud weight window. It predicts a synthetic borehole failure image based on the current mud weight, well trajectory, and the applied failure criterion. For the 3DMEM construction, the data of 1DMEMs of studied wells are upscaled into the grids and spatially distributed using the kriging geostatistical method (Aminzadeh and Dasgupta 2013).

Results and discussion

Numerous calculations have been made on the Well logs to reveal elastic properties, rock strength, vertical and horizontal principal stresses, and pore pressure. These geomechanical parameters of the (8½ʺ) section extending from Sadi to Zubair formations are evaluated at each Well and integrated to build 3DMEM of the X-Field.

Elastic properties

The calculated Static Poisson's ratio (PR_STA) was relatively high in limestone zones (0.22–0.28) and low in sandstone intervals (0.18–0.23), while shale has comparatively higher values than the sandstone rocks (0.20–0.24). However, the shale beds did not show consistent behaviour. The Poisson's ratio values from laboratory tests (Lab_PR) were in the range of (0.25–0.3) in the limestone zones and 0.21 in shale beds. Poisson's ratio varied vertically with the stratigraphic column as demonstrated in Fig. 1 between (0.18–0.28). The Sadi and Ahmadi formations have Poisson's ratio between 0.25 and 0.28. In the Zubair reservoir, it falls between 0.19 and 0.23. The lateral variations in Sadi formation are in the range of 0.26 to 0.27, as presented in Fig. 2. Generally, the Poisson's ratio decreases towards the North of the field, which means that instability issues in the Sadi formation are less in the north area than in the south.

The results of Static Young's modulus (YME_STA) decreased in shaly beds (1.17–4.67 Mpsi) and sandy intervals (2.29–3.28 Mpsi) and comparatively increased in limestone formations (2.28–5.53 Mpsi). The Young's modulus values from laboratory tests (Lab_YME) were in the range of (1.96–5.37 Mpsi) in limestone zones and 4.02 Mpsi in shale beds. Young's moduli showed minor ertical variations (1.17–5.53 Mpsi), as demonstrated in Fig. 3. The Sadi formation has Young's modulus between 2.04 and 2.7 Mpsi. In Khasib, Rumaila, and Shuaiba formations, it falls between 2.15 and 5.53 Mpsi. Horizontally, there is significant heterogeneity in the Shuaiba formation (Fig. 4) grouped in three areas, which revealed the relation between the field's rock mechanical properties and structural geology. The south area has values of Young's modulus between (3.0 and 3.5 Mpsi), the north area between (3.5 and 4.0 Mpsi), and the middle space between (4.0 and 4.5 Mpsi). Hence, it is clear that the wellbore instability problems are most likely to occur in shale intervals than other units because of the relatively high Poisson's ratio and low Young's modulus. Accordingly, the drilling mud weight in Tanuma, Ahmadi, Nahr Umr, and Zubair formations must be determined carefully. In addition, surge and swab should be avoided while drilling these formations, especially with highly deviated Wells.

Rock strength properties

The calculated friction angle (FANG) was relatively high in limestone (30°–38°) and sandstone (31°–35°) intervals and low in shale beds (26°–35°). The highest friction angle values are found in Khasib formation (32°–39°), and Mishrif reservoir (34°–38°), and the lowest values were in the Zubair reservoir (26°–34°), as presented in Fig. 5. The contour maps of Mishrif in Fig. 6 showed lateral friction angle variations (33°–38°). The southern area shows higher values of friction angle, and accordingly, the chance of Well-instability problems is fewer.

he unconfined compressive rock strength (UCS) predictions showed high values in limestone (9300–18,700 psi), moderate in sandstone (9900–11,700 psi) and low in shaly intervals (5000–17,000 psi). The UCS in Khasib, Mishrif, Rumaila, and Shuaiba formations were between (9000–18,700) psi, as presented in Fig. 7. Since the tensile strength (TSTR) is calculated from the UCS, the TSTR and UCS display the same distribution. There are apparent heterogeneous regions with rock strength (UCS) which plays a crucial role in wellbore stability analysis. In Khasib formation, it decreases towards the field's northern area in the range between (5000 and 19,000 psi) (Fig. 8).

Overburden stress and pore pressure

The 3D model of the overburden stress clearly confirms that the vertical stress increases with depth (Fig. 9). The vertical stress of the constructed model from Sadi to the end of Zubair formation falls between 6060 and 11,325 psi.

Pore pressure estimation utilizing Eaton's method gave acceptable values for the shale zones comparable to the MDT result in the permeable zones. For non-shale zones, normal pore pressure (hydrostatic pressure) is determined using the average normal pore fluid density in X-field. The 3D pore pressure distribution results showed a depletion region against the Mishrif reservoir (2700–3400 psi) and Zubair reservoir (4140–4320 psi) in the North of the study area. On the other hand, only the Zubair reservoir (4020–4560 psi) is depleted in the south of X-field (Fig. 10). Figures 11 and 12 revealed that the pore pressure values variation towards the northern area of the field in Zubair and Mishrif reservoirs.

Horizontal stress magnitude

The maximum horizontal stress is highly affected by Young's modulus, while the minimum horizontal stress is relatively consistent with Poisson's ratio. The rocks with a higher Poisson's ratio revealed higher horizontal stress. The 3D stress distribution models (Figs. 13 and 14) showed a stress variation through the stratigraphic column. It is observed that there are considerable variations in maximum horizontal stress magnitudes (6000–13,500 psi). The highest maximum principal horizontal stress is observed in Shuaiba formation in the range of (9900–13,500 psi). In Zubair/upper shale reservoir, the range was less than that in the Shuaiba formation (9000–10,000 psi). Generally, the studied field's dominant stress regime was Strike-Slip, which prevailed in the limestone sections except for Maudud Formation reporting a Reverse regime. In addition, the Normal fault regime was predominant along shale beds.

Horizontal stress direction

The image logs and four-arm caliper logs (C1 and C2) data were obtained from the last Sect. (8½) of Well N1. A standard image processing workflow was implemented with the default parameters to produce static and dynamic images. Then, the breakouts are identified along with the studied interval. In Fig. 15, the picked breakout at depth (3195–3196.5 m) was oriented about 140°–150° clockwise from the North and shown in two scales: FMI and 2-arm caliper. Rose diagram (Fig. 16) presented the average orientations of the picked breakouts along the studied section which revealed that the direction of minimum horizontal stress (breakouts orientation) towards NW–SE, about 140° or 320°. Since the maximum horizontal stress direction is orthogonal to minimum horizontal stress, the orientation of maximum horizontal stress is in NE-SW about 50° or 230° (Fig. 17).

Wellbore stability analysis

The wellbore stability of a vertical well is investigated from Sadi formation to Zubair reservoir. The safe drilling-fluid density range for maintaining wellbore stability is determined and simulated using the Mogi-Coulomb failure criterion. Figure 18, Tack_4 displays the limits of the mud weight window, and the possible kick is marked near the right boundary of the grey shaded area as indicated by the magnitude of the mud weight. Alternatively, the minimum mud weight required to prevent shear failure (breakout) is restricted to the right boundary of the yellow shaded area. The minimum horizontal stress gradient is reserved to the left limit of the light blue area, but the formation breakdown pressure gradient is delineated by the left boundary of the dark blue area. The predicted borehole failures were wide breakouts (red-coloured, σθ > σz > σr), shallow knockouts (green-coloured, σz > σθ > σr), and high angle echelon (blue coloured, σz > σr > σθ) as presented in Track 5. Mogi-Coulomb failure criterion showed a higher level of compatibility with the Well observations and actual wellbore failure displayed by the caliper log in Track_6 and Track_7.

A sensitivity analysis at single depths was conducted to determine the influence of Well deviation and azimuth on the mud weight window. At depth 2267 m TVD (Mishrif formation), a single depth sensitivity analysis was implemented and visualized on both stereonet plots and line plots. Figure 19 illustrates the maximum mud weight that prevents formation breakdown with azimuth and deviation. Wells in the azimuth of minimum horizontal stress has the highest breakdown mud weight, especially for a high-inclination or horizontal wells. Fractures do not seem likely to occur in an inclination between about 40° and 90° towards the minimum horizontal stress. Figure 20 presents a polar plot that shows the minimum mud weight required to avoid breakout with Well azimuth and deviation. This plot suggested that the low deviation Wells are more stable in all directions. Therefore, the optimum conditions to drill a stable borehole at this depth are to drill the boreholes towards the minimum horizontal stress with a deviation of less than (50°). The line plot in Fig. 21, the mud weight window with a deviation (0 –90°), showed that the mud weight window is narrowing for inclinations above 25°. Figure 22 presented the safe mud weight window as a function of azimuth (0–360°) and revealed that the azimuth has no effect on the mud weight window at this depth and current inclination.

However, the single depth sensitivity analysis is limited for a specific depth and does not determine the trajectory for a particular interval. Hence, the forecasting of mud weight and Well-trajectory is performed along with the studied interval. The stability forecasting was accomplished by implementing borehole sensitivity analysis with different parameters of mud weigh (11–12.6 ppg) and deviation (0°, 30°, 50°, 60°, 80°, 90°), along an azimuth parallel to the orientation of minimum horizontal stress (Fig. 23) as proposed by single depth sensitivity analysis in the troublesome shale intervals.

Conclusions

The conclusions are made according to the obtained results as follows:

-

Shale has high Poisson's ratio, low Young’s modulus, low friction angle, and low rock strength. Therefore, the planned wells should be carefully designed to avoid the instability problems in Tanuma, Ahmadi, Nahr Umr and Zubair formations where they are dominated by shale.

-

Pore pressure was depleted in the Zubair reservoir for the South X-field and in the Mishrif and Zubair reservoirs for the North X-field.

-

3DMEM shows relative heterogeneity in most rock properties and field stresses between the southern and northern X-field.

-

Drilling the deviated and horizontal Wells towards the minimum horizontal stress (140° from the North clockwise) has less stress anisotropy, and accordingly, less likely of shear failures across the hazard intervals.

-

Vertical and slightly inclined Wells (less than 40°) are more stable than the highly deviated and horizontal Wells.

-

Increasing the current mud weight by (0.5–1.5) ppg will prevent the breakout failure. The proposed mud weight for the directional Wells extends between (12–12.6 ppg).

References

Aadnoy BS, Looyeh R (2011) Petroleum rock mechanics drilling operations and well design, Gulf Professional Pub

Abbas AK, Alameedy U, Alsaba M, Rushdi S (2018) Wellbore trajectory optimization using rate of penetration and wellbore stability analysis. In SPE international heavy oil conference and exhibition. Society of Petroleum Engineers

Abdulridha HL, Dahab A, Abdulaziz A (2020) 3d mechanical earth model for optimized wellbore stability a case study from South of Iraq. Master thesis. Faculty of Engineering. University of Cairo

Aminzadeh F, Dasgupta SN (2013) Reservoir monitoring. In: Developments in petroleum science, vol 60. Elsevier, pp 191–221

Baker Hughes (2017) JewelSuite GeoMechanics user manual

Eaton BA (1975) The equation for geopressure prediction from well logs. In: Fall meeting of the society of petroleum engineers of AIME. Society of Petroleum Engineers

Fjar E, Holt RM, Raaen AM, Horsrud P (2008) Petroleum related rock mechanics. Elsevier

Higgins SM, Goodwin SA, Bratton TR, Tracy GW (2008) Anisotropic stress models improve completion design in the Baxter Shale. In SPE annual technical conference and exhibition. Society of Petroleum Engineers

Kadyrov T, Tutuncu AN (2012) Integrated wellbore stability analysis for well trajectory optimization and field development in the West Kazakhstan Field. In 46th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium. American Rock Mechanics Association

Manshad AK, Jalalifar H, Aslannejad M (2014) Analysis of vertical, horizontal and deviated wellbores stability by analytical and numerical methods. J Petrol Explor Product Technol 4(4):359–369

Matanovic D, Cikes M, Moslavac B (2012) Sand control in well construction and operation. Springer Science & Business Media

Mitchell J (2001) ‘Trouble-Free Drilling’. Drilbert Eng 1

Plumb RA (1994) Influence of composition and texture on the failure properties of clastic rocks. In Rock mechanics in petroleum engineering. Society of Petroleum Engineers

Schlumberger (2018) Techlog user manual

Zamora Valcarce G, Zapata T, Ansa A, Selva G (2006) Three-dimensional structural modeling and its application for development of the El Portón field. Argentina AAPG Bull 90(3):307–319

Zhang JJ (2019) Applied petroleum geomechanics. Gulf Professional Publishing

Zoback MD (2007) Reservoir geomechanics. Cambridge University Press

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Thiqar Oil Company (TOC) and Missan Oil Training Institute (MOTI) for supplying the technical datasets and the facilities to perform this study.

Funding

There is no funding source for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the co-authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

On behalf of all the co-authors, the corresponding author states that there are no ethical statements contained in the manuscripts.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdulaziz, A.M., Abdulridha, H.L., Dahab, A.S.A. et al. 3D mechanical earth model for optimized wellbore stability, a case study from South of Iraq. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 11, 3409–3420 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-021-01255-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-021-01255-6