Abstract

Despite its complexity and importance in managing water resources in populous deltas, especially in tidal areas, literatures on tidal rivers and their land use linkage in connection to water quality and pollution are rare. Such information is of prior need for Integrated Water Resource Management in water scarce and climate change vulnerable regions, such as the southwestern coast of Bangladesh. Using water quality indices and multivariate analysis, we present here the land use signatures of a dying tidal river due to anthropogenic perturbation. Correlation matrix, hierarchical cluster analysis, factor analysis, and bio-geo-chemical fingerprints were used to quantify the hydro-chemical and anthropogenic processes and identify factors influencing the ionic concentrations. The results show remarkable spatial and temporal variations (p < 0.05) in water quality parameters. The lowest solute concentrations are observed at the mid reach of the stream where the agricultural and urban wastewater mix. Agricultural sites show higher concentration of DO, Na+ and K+ reflecting the effects of tidal spill-over and shrimp wastewater effluents nearby. Higher level of Salinity, EC, Cl−, HCO3−, NO3−, PO43− and TSS characterize the urban sites indicating a signature of land use dominated by direct discharge of household organic waste into the waters. The spatial variation in overall water quality suggests a periodic enhancement of quality especially for irrigation and non-drinking purposes during monsoon and post-monsoon, indicating significant influence of amount of rainfall in the basin. We recommend that, given the recent trend of increasing precipitation and ground water table decrease, such dying tidal river basins may serve as excellent surface water reservoir to supplement quality water supply to the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

River water chemistry is controlled by many natural and anthropogenic factors. Anthropogenic factors such as land use is well known as one of the major influences on the hydrochemistry of the rivers (e.g., Rothwell et al. 2010; Pratt and Chang 2012; Huang et al. 2013a, b, etc.). Anthropogenic activities are increasing day by day leading towards conversion of pristine lands, increasing urban residences, surface water runoff, wastewater input and dwindling forested lands and wetlands. Literatures suggest the practice of land use changes has an impact spanning from local to global scale (e.g., Wilson and Weng 2010; Yang et al. 2012; Hur et al. 2014; Roy et al. 2015, etc.), ranging from changes in the global carbon cycle (e.g., Pielke et al. 2002; Kalnay and Cai 2003; Don et al. 2011; Poeplau et al. 2011, etc.), through changes in surface energy and water balance to widespread effects on water quality (e.g., Foley et al. 2005; Shen et al. 2014, 2015). It has been observed that, the water chemistry parameters synchronously vary with the changes of land use pattern (e.g., Zhou et al. 2012) and hydrological dynamics (e.g., Zhang et al. 2014). Runoff is largely affected by physical alteration of the landscapes (e.g. Tang et al. 2005; Valentin et al. 2008; Nunes et al. 2011). The relationship between water quality and land use, however, may be concealed by other factors complicating to obtain a distinct hydro-chemical signature (e.g., Kang et al. 2010; Huang et al. 2013a, b; Bu et al. 2014, etc.). Thus, the study of stream hydrochemistry is important in revealing the pattern and linkage between evaporation, chemical weathering, precipitation and anthropogenic impacts (e.g., Gibbs 1970; Meybeck 1987; Brennan and Lowenstein 2002; Rothwell et al. 2010; Tran et al. 2010; Mitchell et al. 2013). Quantifying the major ion composition of stream waters also has broad implications, i.e., water type, hydrogeology characteristics, weathering processes and rainfall chemistry. These researches featured in scientific literatures over 50 years (e.g., Gibbs 1970; Brennan and Lowenstein 2002; Nordstrom 2011). Understanding how land use and land cover change influence the flow and water quality of rivers is of utmost importance for river management and restoration (e.g., Barbosa et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2013a, b).

However, despite land use and its linkage with hydrochemistry being center of attention to many researchers in the recent past, tidal rivers in populous deltas have attracted little attention. Tidal rivers in coastal deltas are dynamic in terms of variations in settings (e.g. Well 1995); changes of courses (e.g., Zhang et al. 2010), rate of accretion and erosion (e.g., Rogers et al. 2013) and the amount of water discharge/intake over short period. Such characteristics of tidal rivers lead to dynamic changes to coastal landscape. Due to high diversity and biological resources, such river basins are also exposed to maximum human perturbation resulting in various land use (e.g., Auerbach et al. 2015; Gain et al. 2017; Mutahara et al. 2017). The dynamism of tidal rivers, frequent changes in flow and multipurpose use of land resources poses complex impacts of the hydrochemistry and water quality. Therefore, integrated water resource management in such regions is quite difficult and requires in-depth research efforts and high-resolution monitoring data.

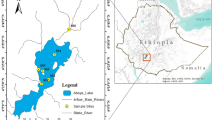

The southwestern costal region of Bangladesh is one of top vulnerable regions in the world due to Climate Change (CC) and Sea Level Rise (SLR) (e.g. Mondal et al. 2013; Auerbach et al. 2015, Roy et al. 2017). The region is also one of the examples of massive anthropogenic perturbation and degradation in water quality (e.g. Brammer 2010; Auerbach et al. 2015; Ayers et al. 2016, 2017; Roy et al. 2017). Our study area concentrates on the Mayur river basin, a major tributary of the Bhairab river system (Fig. 1). The Bahiarab river system is one of the major systems that flows through the southwest delta of Bangladesh. This heavily populated delta (~ 14 million, calculated from BBS 2011) has evolved around this river. Originated from a beel (wetland system) river Mayur contributes fresh water to the Bhairab system and provides irrigation for ~ 48,000 ha of farmland. Besides the river supports aquaculture and provides base flow for the surrounding groundwater system. Over last 30 years Mayur has become an ephemeral tidal river and now-a-days gets disconnected from its source during dry season. However, tidal influence is quite active at the confluence with the river Bhairab. The river, besides irrigation and aquaculture, is used as the municipal wastewater drainage along with industrial discharges from ~ 1500 industries and factories. Because of the rivers ephemeral character, its capacity to assimilate and eliminate pollutants from water is gradually reducing. In the context of declining ground water table in the city (Fig. 2), salinity intrusion and growing demand for potable water, search for an alternative water source is now of utmost importance. The state of current water chemistry, land use pattern in the drainage basin, rainfall runoff, water use conflicts, etc. can be major determinants for the potentiality of the Mayur as an option. To start with, this river deserves a deeper insight to its chemistry and sources of pollution.

Researchers have employed many statistical applications all over the world to investigate the linkage between land use and water quality. These applications include Correlational Analysis (CA) (e.g., Bu et al. 2014), Multiple Regression Analysis (MRA) (e.g., Kang et al. 2010), Redundancy Analysis (e.g., Shen et al. 2015) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (e.g., Villegas et al. 2013). In this study, major ion composition of the Mayur River has been examined and spatio-temporal patterns indicative of their source are investigated as well as the control mechanisms of ion chemistry is explained through various multivariate statistics and water quality indices. In addition, this dying tidal river’s potential as a surface water resource has been inspected through drinking and irrigation water quality analysis. It should be noted that, although use of multivariate techniques to identify the linkage between hydrochemistry and land use is quite common and popular in scientific community to reveal the management strategy, this is the first attempt to apply such a technique for a tidal river in Bangladesh.

Study area

Our study concentrates on the tidal river basin of Mayur, located at the back swamp of the river Bhairab. The river is originated from a large wetland system called beel Pabla and nowadays is ~ 11 km long with 22 canals and one river joining in its course. While its right bank is industrialized and receives municipal and industrial waste, the left bank characterized with wetlands and agricultural lands being irrigated with its water (Fig. 1). Due to the river’s geographical location, the river shares the basin of river Bhairab’s large tidal basin. Although river Mayur serves fresh water to the river Bhairab during monsoon and post-monsoon, tidal impacts are heavy at the confluence of these rivers. Because of wastewater discharge to this river, it is also subject to a massive anthropogenic perturbation (Rahman et al. 2014). It is embanked on both heads to create land for aquaculture. A large 10-vent sluice gate controls the southern end of the river (lower reach) to control tidal floodwater from river Bhairab. The northern end (upper reach) is also embanked to reserve beel Pabla’s water. These interventions practically accelerated the death of the river. However, the river still serves irrigation water for the whole basin and plays critical role in maintaining the local groundwater table.

The river basin is composed of various morphological features such as flood plain, flood basin, swamp, and abandoned channel (Roy et al. 2005). The elevation of this tidal basin varies between 1.2 and 3.8 m. The region lies on the Ganges deltaic plain in north and Ganges tidal plain in south of Holocene–Recent age (Adhikari et al. 2006). Tectonically, the area lies within the Faridpur Trough of Foredeep Bengal Basin. No subsurface fault has been demarcated in the region. Lithologically, the area is composed of very fine sand, silt and silty clay up to a depth of 300 m with peaty soil and calcareous as well as non-calcareous soil at the top.

Materials and methods

Sampling and analysis

Surface samples were collected from the river and its adjoining canals over four seasons: pre-monsoon, monsoon, post-monsoon and winter. Samples were collected at depths 40–50 cm from the water surface approximately at the middle parts of the river. The water samples were filtered (0.45 Millipore filter) in the field and stored in acid washed polypropylene bottles. Cleaning of plastic bottles and plastic bags was carried out by soaking in 5% (v/v) HNO3 for 24 h and then rinsing with milli-Q water. After collection of water samples, the bottles were securely sealed with proper labeling (sample number, location name and date). Aeration during sampling was avoided as far as possible. The water samples were carefully transported to the laboratory and preserved for chemical analysis. Total analysis was carried out within 15 days of collection. The detail sampling and analytical methods for the water samples have been described elsewhere (APHA 1992; Ramesh and Anbu 1996).

Physical measures such as pH, electrical conductivity (EC), dissolved oxygen (DO) and total dissolve solids (TDS) were determined by portable water quality multiprobe meter (HACH Hydrolab Multiparameter Sonde 4a) in field. Na+ and K+ were measured by Flame photometric method (Flame photometer—models PEP 7), and Ca2+ and Mg2+ were determined by titrimetric method (Ramesh and Anbu 1996). HCO3− was analyzed by potentiometric method while Cl− was quantified by ion electrode method (Cole-Parmer R 27502-22, -23). PO43− and SO42− were determined by ascorbic acid method and turbidimetric method, respectively (Thermo spectronic UV–visible spectrophotometers, Helios 9499230 45811) and dissolve silica (H4SiO42−) was analyzed by molybdo-silicate method (Thermo spectronic, UV–visible Spectrophotometers, Helios 9499230 45811) (Ramesh and Anbu 1996).

Basin delineation and bathymetric survey

The Mayur River watershed was divided into three zones through integrated watershed delineation using DEM dataset provided by SRTM v.4.1 and land use characters were obtained from Khulna Development Authority (kDa). River cross-sections were taken along 12 chains to calculate Mayur’s water retention capacity. Calculation was done using the trapezoidal volume equation. The adjoining 22 canals and one distributary were not considered for cross-sectional measurements.

Multivariate analysis

Pearson correlation analysis for Mayur basin was carried out to evaluate the relationships between various physiochemical parameters, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) and factor analysis (FA) were performed to reveal the underlying structure of the dataset by means of distance between variables in a multi-dimensional space. Ward linkage with Euclidean distance was used for HCA. Principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation was used for extraction and deriving factor derivation in FA. The statistical processes and their applications are stated elsewhere (e.g., Singh et al. 2004).

Results

Spatio-temporal characteristics of hydrochemistry

A summary of the hydrochemistry of the study area is presented in Table 1. Hydro chemical parameters show remarkable spatio-temporal differences (p < 0.05). DO, Salinity, EC and TDS rise about two orders of magnitude from pre-monsoon to post-monsoon. Of the cation budget, Na+ shares the major load (69.7%, averaged over four seasons). Second to Na+, K+ shows highest load (21% of total cationic load) in pre-monsoon, while Ca2+ shares the second highest cationic load in every other season (29.63% in monsoon, 23.16% in post-monsoon and 14.40% in dry season). Mg2+ has been found as the least abundant cation. The cationic order was found as: Na+ > K+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+. Cl− dominates the anionic load (43.20%, averaged over four seasons) with an average of 334.34 ± 399.02 mg/L followed by HCO3− (39.90%, average 308.78 ± 134.16 mg/L). The mean values of Cl− and HCO3− load are nearly equal. HCO3− load over total anions vary significantly over seasons, showing an increasing trend from pre-monsoon (33.58%, median value) towards dry season (59.40%, median value). Beside Cl− and HCO3−, the other most abundant anion is SO42− (avg. 123.11 ± 163.10 mg/L) which also shows a marked temporal variation and decreasing trend on total anion load from pre-monsoon (30.93%, median value 287.79 mg/L) towards dry season (3.04%, median value 20.22 mg/L). NO3− and PO43− are least abundant anions found (5.97 ± 2.73 and 5.03 ± 0.35 mg/L, respectively). The anionic order was found as Cl− > HCO3− > SO42− > NO3− > PO43−.

Significant spatial variations of major ions may indicate the origin of water chemistry at sub-watershed level (e.g., Chen et al. 2002). The distribution of physico-chemical parameters over high tide and low tide separated by head waters and tail waters may give better insight while investigating possible source of the ions. With temporal variation, the major ions also show significant spatial variation (Fig. 3). Of the major ions Na+, K+, Mg2+, Cl−, SO42−, NO3− and PO43− show high spatial variation over the full cycle of sampling (C.V. > 50) in the order of PO43− > SO42+ > K+ > Cl− > Na+ > Mg2+ > NO3−. Generally abundance of major ions decreases from upper reach to lower reach. Except HCO3− all the major ions show rising trend towards the discharge point. This confirms the strong tidal influence in these sampling stations.

Major ion composition and correlation

Pearson correlation was examined among the major ions and other physical parameters measured (Table 2). Significant (p < 0.05) and strong (r ≥ 0.80) correlations have been found between salinity and Na+, K+, TDS and TSS; Na+ and K+, and TDS and TSS; K+, and TDS and TSS; and TDS and TSS. Significant (p < 0.05) and moderate (r ≥ 0.60 to < 0.80) correlations have been found between DO and HCO3− (negative); temperature and SiO2 (negative); salinity and SO42− and Mg2+; EC with Cl−; Na+ with Mg2+ and SO42−; K+ with Mg2+ and SO42−; Mg2+ and Cl−, SO42−, TDS and TSS; HCO3− and PO43−; and SO42+ and TDS and TSS. While Cl− shows very weak (0.088) and insignificant (p ≫ 0.05) correlation with salinity, strong to moderate correlation between salinity and Na+, K+, Mg2+ and SO42− suggests that it may originate from the urban wastewater released in the head waters of the river. As Na+ significantly (p < 0.05) and moderately (r ≥ 0.60 to < 0.80) correlated with Mg2+ and SO42−, while Mg2+ is further correlated with Cl− and SO42−, it is most likely that Na+, Mg2+, Cl− and SO42− may share the same origin. The significant association of HCO3− and PO43− (p < 0.01, r = 0.627), NO3− and HCO3− (p < 0.01, r = 0.458) and NO3− and PO43− (p < 0.01, r = 0.407) also indicative soil leaching and agricultural runoff.

Water types

Plotting of TDS concentrations against the weight ratios of Na/(Na + Ca) for the upper Mayur river revealed (Gibbs 1970) that the river water is characterized by a very high ratio of Na/(Na + Ca) and a high TDS concentration (mostly > 1000 mg/L during winter, pre-monsoon and monsoon) (Fig. 4a), typical of evaporation–crystallization dominated rivers. To be further in depth, Piper trilinear diagram (Piper 1944) of major ion compositions was constructed (Fig. 4b). The plot shows a cyclic pattern of data association. In pre-monsoon the data points cluster around the salinity apex with some exceptions, which are clustered towards high-alkali apex. The data points that cluster around the alkali apex are found as headwater samples. This confirms presence of high alkali in the headwaters during the season which causes the excessive salinity as inferred from Pearson correlation (Table 2). In monsoon most of the data points move towards the upper mid of the diamond plot indicating a dilution effect and improving water quality. The cation plot suggests a reduction of Na+ and K+ takes while calcium enrichment is taking place. The anion plot also suggests a marked reduction in SO42− with HCO3− enrichment. In post-monsoon the data points further move down to the mid of the diamond plot with wide distribution with further addition of HCO3− and further reduction of SO42−. Although the cations are found widely distributed, it still indicates a slight reduction of both Ca2+ and Mg2+ and addition of Na+ and K+. In winter, data points tend to move slightly towards the salinity apex with additional Na+, K+ and HCO3− input and further reduction of Ca2+ and SO42−.

Discussion

Mechanisms controlling the major ion chemistry

Cyclic salts

Rainwater runoff and ground water discharge are the major sources of base flow in the Mayur River. Therefore, cyclic sea salts in the dissolved load of the river is expected to carry the signatures of rainfall and groundwater in the region. Generally, the contribution of cyclic salts to riverine dissolved salt loads is expected to decrease with increasing distance from the sea. It has been long established that, Cl− in river waters with no terrestrial sources of the element declines systematically as a function of increasing distance from the sea (Stallard and Edmond 1981). The reverse has been found in the Mayur River. Although the basin of Mayur is small (~ 11 km long river with 52 km2 basin area) increasing amount of Cl− towards the upper reaches is noticeable. While Cl− was found as 217 mg/L in the lower reaches of the river (average value of four most downstream stations), upper reaches show 326.8 mg/L of Cl− (average value of four most upstream stations). This indicates the high concentration of Cl− in the Mayur River likely to be originated from either weathering of evaporites or anthropogenic inputs. However, The 22 drains discharging urban effluents into the river cancels out the possibility of evaporites being the major contributing source of Cl− in the river and indicates that the source of water in river Mayur is mostly urban waste rather than rainfall and groundwater discharge.

Weathering

The Piper trilinear plot (Fig. 4b) demonstrates significant variation in water types over the year. From winter towards pre-monsoon data points cluster more towards the salinity apex (Na-SO4 type), while Na+ and Cl− remain more or less same for the both cases but SO42− increases in the pre-monsoon compared to the winter samples. In the cations trilinear plot, data points move more towards the Na apex from winter to pre-monsoon suggesting additional Na+ discharge to the dissolved load. In the anion plot, while data points cluster around high HCO3− and low SO42− in winter, pre-monsoon is marked with SO42− enrichment replacing HCO3−. This exhibits the effect of lack of rainfall in winter followed by pre-monsoon, consequently increasing the pollution effect, as HCO3− concentration does not change much (med. value 394 mg/L in winter and 312 mg/L in pre-monsoon) but SO42− concentration increases from 20.22 mg/L in winter (median value) to 287.78 mg/L in pre-monsoon (median value). In monsoon and post-monsoon, in contrast to that of winter and pre-monsoon, data points float widely in the middle of the diamond plot. However, in monsoon, a reduction of Na+ and enrichment of Ca2+ is noticed, indicating a dilution effect. Post-monsoon data points show wide and variant combination of Na+, Ca2+ and SO42− suggesting infrequent freshwater mixing with pollution caused by irregular and but intense rainfall.

Wide distribution of data points in the trilinear plot indicates the influence of anthropogenic activities in the dissolved load rather than weathering effects. The concentration ratio of HCO3:Cl + SO4:SiO2 has been found as 31:36:1 in the dissolved load and the correlation between SiO2 and Ca2+, K+, HCO3− and SO42− are negative and very weak (< |0.3|) but significant (Table 2). This suggests that silicate weathering plays a less important role in determining major ions for the whole basin. Again, most of the data point fall below the equiline of HCO3/Cl + SO4 (Fig. 5a) and HCO3/Na + K (Fig. 5b) and cluster around the equiline of HCO3/Ca + Mg (Fig. 5c) indicating that the weathering of carbonates and/or evaporites cannot explain the whole composition of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the water. While most of the data points fall below the isometric line of Ca + Mg/Na + K (Fig. 5d) and Cl + SO4/Na + K (Fig. 5e), almost all data points clustering above the Cl + SO4 = Ca + Mg line (Fig. 5f) indicate that neither evaporate weathering nor the carbonate weathering is the dominant process in the basin.

High concentration of Na+ and Cl− in natural waters usually indicates halite dissolution which may not be case in this river basin. In majority of the cases (~ 66%) Na+ has been found comparatively lot higher than Cl− as the Na+/Cl− ratio shows an average of 2.71. This cancels out the dominance of halite dissolution and suggests possible ion-exchange process, if not the presence of silicate weathering, which in this case has been proved as less dominant earlier. This cation exchange process involves excess Na+ input by the city wastewater lines.

Ion exchange

As depicted in Fig. 6a, the Na+ concentration of most the samples (66.66% of total) scattered above the seawater line, which suggests excess Na+ enrichment in the Mayur waters except in monsoon (Na+/Cl− = 0.96). This excess Na+ might be influenced by cation exchange process. To further investigate the occurrence of cation exchange reactions in the studied waters, a Na–Cl versus Ca + Mg – (HCO3 + SO4) plot was constructed (Fig. 6b). Apart from cation exchange the most likely additional sources of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in natural waters are Calcite, dolomite, gypsum and anhydrite weathering. While plotting the diagram, the lithogenic Na+ available for exchange is calculated from Na+ to Cl− as it is assumed that the meteoric Na+ should be balanced by equivalent concentration of Cl− (Nkotagu 1996). Again, possible contribution of Ca2+ and Mg2+ from Calcite, dolomite, gypsum and anhydrite dissolution lo lithogenic Ca2+ and Mg2+ are accounted for by subtracting the equivalent concentrations of HCO3− and SO42− (Nkotagu 1996). Figure 6b suggests the excess Na+ in pre-monsoon and winter season may be due to cation exchange of Na+ replacing Ca2+ and/or Mg2+.

Water quality

The TDS–TH ratios indicate water quality changes over time from hard brackish water in pre-monsoon to mostly hard fresh water in all other seasons confirming dilution effect in wet period. If only TDS is accounted for 58.33% of the samples fall in permissible limit for drinking water, all of which are found in monsoon and post-monsoon season (Table 3). According to the irrigation water classification based on the Sodium Absorption Ratio (SAR), most of the samples (64.58%) fall in poor category indicating poor water quality along the river. However, ~ 66% of the samples in monsoon fall in excellent to good category suggesting improvement in water quality in the monsoon. The EC-based classification further show that 93.75% samples fall in good to permissible category during monsoon. No sample was found as excellent quality.

Land use signatures on water

Multivariate techniques were applied to investigate the major land use sources of ion chemistry in the river. For this analysis, only river water samples were considered, since the adjoining canals bring area specific discharges to the river. The results of Factor Analysis (FA) are presented in Table 4. Four factors were extracted using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based on the condition “eigenvalue > 1” explaining 79.99% of the total variation. Factor 1 explains 38.10% of the variation and has strong loading (≥ 0.75) on Salinity, TDS, TSS, Na+, K+, Mg2+ and SO42−. Since weathering effects are not strong in the river basin except land runoff and the river is dead at its source, this factor can be explained as the anthropogenic factor, most likely the urban influence. Figure 6 presents a spatial distribution of the factor coefficients along the river. This distribution suggests head waters of the river show high factor 1 coefficients which is most populous part of basin. The second factor explains 20.06% variation in the data and exhibits strong positive loading on HCO3− and PO43− and strong negative loading on DO and moderate (≥ 0.50 ~ ≤ 0.75) positive loading on NO3− and moderate negative loading on pH. This may represent the agricultural/soil runoff signature. Agricultural activities are known to have a major impact on hydrochemistry of streams. The use of N and P fertilizer is common in the Mayur river basin as more than 60% of the total basin area falls under agricultural land use. NO3− was found as high as 5.97 and 5.05 mg/L (median value) in pre-monsoon and winter, respectively. PO43− was found as 5.02 and 4.94 mg/L (median value) in the same seasons reported earlier compared to 0.35 and 1.04 mg/L in monsoon and post-monsoon, respectively. This indicates the seasonality of the agricultural practices in the basin, as the winter rice called Boro is cultivated around these seasons. Figure 7 reveals a peak of factor 2 in the middle reaches of the river where agricultural activities are concentrated. A third factor explains 12.70% of the data variation and has a strong positive loading on EC, Ca2+ and Cl− with moderate positive loading on Mg2+. This is likely to be the effect of tidal influence in river during the wet season (Fig. 7). The fourth factor has a strong negative loading on water temperature and strong positive loading on SiO2 with moderate positive loading on pH explaining 9.10% of the total variation explained. Naturally pH is inversely related with SiO2 which has been found reverse in this case. Therefore, it can be assumed that, this factor explains the massive construction works involving the use of silica that is taking place alongside the river mostly during winter (or dry season). The values of SiO2 found in the river over the seasons support this theory as in winter SiO2 in the water samples are found as 23.55 mg/L (median value) while in pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon corresponding avg. values are 4.18, 7.3 and 4.32 mg/L, respectively (Fig. 7).

Spatial distribution of the factors extracted from factor analysis (FA). F1–F4 denote the four factors extracted, C1–C4 denote sampling cycles where C1 pr-monsoon, C2-monsoon, C3 post-monsoon, C4 winter, HT high tide, and LT low tide. Station 1 represent head waters while station 12 indicate tail waters with tidal influence

The HCA was performed based on the major cations, major anions and the physical parameters, which produced three main clusters (Fig. 8a). Interestingly, the clusters give a clear indication of changing water quality and dominant land use types running along the river. First five sampling stations fall in cluster 1 which are located in the upstream and dominated by urban land use. The last three stations at the downstream are clustered together and are dominated by agriculture. The third cluster represents four sampling stations located in the middle reach of the river organized among two sub-clusters indicating a mix of the two dominant land use types, urban and agriculture. However, interestingly, the major two land use dominated clusters (agriculture and urban) are grouped in one mother cluster while the mixed land use show a very different mother cluster. Thus it illustrates how characteristically distinct an agricultural runoff and urban wastewater might be, but the mixture of two can be far different from their original characters.

Land use signature in Mayur river water: a dendrogram produced from hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) showing distinct and dominant land use sites; b Spider diagram showing biogeochemical fingerprints (log normalized to different land uses) of anthropogenic land use. Elements that plot above the x-axis have higher concentrations while elements that plot below the x-axis have lower concentrations in the cluster sites than in the reference sites

The behavior of the hydrochemical variables of each of these clusters is further investigated by developing biogeochemical fingerprints (Fig. 8b). For each cluster, values of the variables are averaged over sites that fall within the cluster and then fingerprints are developed by plotting spider diagrams with the log of the ratio of the median value for each variable in the cluster of interest to the median value for sites in the reference cluster (Wayland et al. 2003). In this spider diagram, points derived from cluster of interest that are plotted on the x-axis (where y = 0) refer to no difference from the reference cluster. The points that plotted over the x-axis (y > 0) indicate higher concentration in the ‘interest cluster’ than that of the ‘reference cluster’ and vice versa.

First, urban cluster was investigated using the agricultural cluster as reference. DO, Na+ and K+ is found as low in the urban cluster while Salinity, EC, Ca2+, Cl−, HCO3−, NO3−, PO43−, SiO2 and TSS is found as high in concentration. These findings are not consistent with available previous researches (e.g., Wayland et al. 2003; Fitzpatrick and Long 2007) as they found higher amount of Na+, K+ and SO42− in urban streams compared to the agricultural streams. The log of urban cluster versus mixed cluster suggests, most of parameters have higher concentration in the urban cluster except DO. Again, the log of the ratio of agriculture versus mixed cluster shows higher concentration (y > 0) of DO, Na+, K+, Mg2+ and TDS and lower concentration (y < 0) of salinity, EC, Cl−, NO3−, PO43−, SiO2 and TSS.

The spider diagram reveals that mixing of urban wastewater leads to higher rate of decreasing DO in streams compared to the agricultural environment. Also, it is clear that urban waste water tends to increase salinity and conductivity in stream water than that of agricultural environment. Agricultural runoff is expected to naturally produce more N and P products along with lesser amount of sodium and potassium compared to the urban streams. This study shows the other way around. Possible explanation for this reverse result can be the influence of shrimp farm end-products in the agricultural sites. There are several shrimp production ponds around the agricultural sites that discharge their waste directly into the river. Shrimp farms are well known for using NaCl and KCl to reduce crop mortality, thus enriching wastewater with Na+, K+ and Cl−. In this case, the agriculture dominated sites of the Mayur River are also rich in Na+, K+ and Cl− and show higher concentration of these ions compared to the mixed water zone (sampling station 6, 7, 8 and 9). This explanation is supported by the fact that the average concentration of Na+ and K+ at the urban, mixed and agricultural sites in the river are 278.04 and 18.96, 166.73 and 15.22, 339.17 and 38.24 mg/L, respectively. The sharp increase of average Na+ and K+ in the agricultural sites indicates the strong influence of shrimp waste in the river. Increase of Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl− and SO42− towards the tail waters of the river where the agricultural sites are found, also are indications of the presence of shrimp farm end-products in water.

Conclusions

The tidal and ephemeral nature of the Mayur river shows significant physico-chemical and spatio-temporal variations and characterized with excessive amount of TDS, Na+, Cl− and SO42− during winter and pre-monsoon but shows dilution effect during the rainy season. Major ion composition is mainly controlled by two types of anthropogenic activities: urban wastewater production and agricultural activities. Weathering effects are weak in the stream, although effects of soil leaching and runoff are evident. Evidences suggest water quality of the river greatly improves during monsoon and post-monsoon and become favorable for irrigation purposes. The piper trilinear diagram also indicates that with rainfall, pollution effects are diluted and the river water becomes more usable (e.g., for irrigation purpose). HCA and FA performed on the river water samples depicted three distinct water groups based on major ion composition; urban wastewater, agricultural runoff and mixed water. However, compared to the previous researches (e.g., Wayland et al. 2003; Fitzpatrick et al. 2007; Yu et al. 2016), these urban waste water and agricultural runoffs showed a little difference in ion composition. Unusual high concentration of Na+ and K+ and low concentration of NO3− and PO43− in the agricultural stream compared with the urban wastewater reflects the presence of shrimp farm end-products in the agricultural sites. Except this, a decrease of DO and increase in salinity, EC and TSS is noticed in the urban streams. Drawing from the analysis and interpretation of major ion chemistry, land use is likely to be the key factor in controlling the water quality of the studied river where amount of rainfall on the basin is a determinant of “improvement”.

Despite some tidal influences at the lower reaches, the river is considered dead for last few decades and now serves as a major supplement for the city drainage system. The southwest region, especially Khulna, the third largest metropolitan city of Bangladesh, is suffering from a sharp decline in dry season ground water table (Fig. 1) for last couple of decades (Roy et al. 2017). Since the river’s water quality gets usable during the rains, it is possible that through restricting municipal and industrial wastewater discharge and adapting proper Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) system addressing land use management system, river Mayur can be used as surface water reservoir for the city. Our bathy survey showed that Mayur can retain ~ 725 million gallon water with its current capacity, which would extend to least 2.5 times after excavation and restoration. By 2030 with an estimated 1.62 million people residing in Khulna city would demand 112 million gallons of supply water per day. The present water supply capacity of Khulna Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (KWASA) is only limited to 14 million gallons per day based on groundwater extraction only. A sharp decline of groundwater table in dry season during recent years is contributing a large cut-off in this water supply. Currently KWASA supplements supply water from a small open lake after treatment. If river Mayur is properly restored through excavation and implementation of IWRM policies adopted by Bangladesh government (see Dewan et al. 2015; Gain et al. 2017; Roy et al. 2017 for a comprehensive review and adoption of the current IWRM policies), a 5% withdrawal of the river water per day (~ 35–40 million gallons) may contribute to reduce the current and future gap between supply and water demand in the region. Although a deeper insight to the groundwater-surface water recharge and interaction is required before making such decisions, the recent increase of annualized precipitation trends in the region (Hossain et al. 2014) presents an opportunity to consider this ephemeral embanked river as a water reservoir in future. The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) has recently (year 2017) adopted the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 (draft) that addresses the nation-wide water challenges through a “hot-spot specific’ issues and strategies (Bangladesh Delta Plan 2017). These issues include coastal flooding and salinity problem and water shortage, drainage and sanitation problem in urban areas. This study is expected to feed the information channel for the scientific, political and other concerned communities to consider possible opportunities of using the river as source of water supply for the city thus contribute to strategic interventions in the coastal urban regions planned by the Bangladesh Delta Plan (BDP).

References

Adhikari DK, Roy MK, Datta DK et al (2006) Urban geology: a case study of Khulna City Corporation, Bangladesh. J Life Earth Sci 1:17–29

APHA (1992) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 18th edn. American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA), Water Pollution Control Federation (WPCF), Washington, DC

Auerbach LW, Goodbred SL Jr, Mondal DR et al (2015) Flood risk of natural and embanked landscapes on the Ganges-Brahmaputra tidal delta plain. Nat Clim Chang 2015:153–157. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE2472

Ayers JC, George G, Fry D et al (2016) Sources of salinity and arsenic in surface water in southwest Bangladesh. Geochem Trans. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12932-016-0036-6

Ayers JC, George G, Fry D et al (2017) Salinization and arsenic contamination of surface water in southwest Bangladesh. Geochem Trans 18:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12932-017-0042-3

Barbosa AE, Fernandes JN, David LM (2012) Key issues for sustainable urban stormwater management. Water Res 46:6787–6798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2012.05.029

Brammer H (2010) After the Bangladesh Flood Action Plan: looking to the future. Environ Hazards 9:118–130. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.2010.SI01

Brennan ST, Lowenstein TK (2002) The major-ion composition of silurian seawater. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 66:2683–2700. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(02)00870-0

Bu H, Meng W, Zhang Y, Wan J (2014) Relationships between land use patterns and water quality in the Taizi River basin, China. Ecol Indic 41:187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.02.003

Chen J, Wang F, Xia X, Zhang L (2002) Major element chemistry of the Changjiang (Yangtze River). Chem Geol 187:231–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00032-3

Davis SN, Dewiest RJM (1966) Hydrogeology. Wiley, Hoboken

Dewan C, Mukherji A, Buisson M-C (2015) Evolution of water management in coastal Bangladesh: from temporary earthen embankments to depoliticized community-managed polders. Water Int. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2015.1025196

Don A, Schumacher J, Freibauer A (2011) Impact of tropical land-use change on soil organic carbon stocks - a meta-analysis. Glob Chang Biol 17:1658–1670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02336.x

Fitzpatrick ML, Long DT (2007) Exploring the effects of urban and agricultural land use on surface water chemistry, across a regional watershed, using multivariate statistics. Appl Geochem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2007.03.047

Fitzpatrick ML, Long DT, Pijanowski BC (2007) Exploring the effects of urban and agricultural land use on surface water chemistry, across a regional watershed, using multivariate statistics. Appl Geochem 22:1825–1840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2007.03.047

Foley JA, Defries R, Asner GP et al (2005) Global consequences of land use. Science 309:570–574. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1111772

Gain AK, Benson D, Rahman R et al (2017) Tidal river management in the south west Ganges-Brahmaputra delta in Bangladesh: moving towards a transdisciplinary approach? Environ Sci Policy 75:111–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.05.020

Gibbs RJ (1970) Mechanisms controlling world water chemistry. Science 170:1088–1090. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.170.3962.1088

Hossain M, Roy K, Datta D (2014) Spatial and temporal variability of rainfall over the south-west coast of Bangladesh. Climate 2:28–46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli2020028

Huang J, Li Q, Huang L et al (2013a) Watershed-scale evaluation for land-based nonpoint source nutrients management in the Bohai Sea Bay, China. Ocean Coast Manag 71:314–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.10.018

Huang J, Li Q, Pontius RG et al (2013b) Detecting the dynamic linkage between landscape characteristics and water quality in a subtropical coastal watershed, southeast China. Environ Manag 51:32–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9793-2

Hur J, Nguyen HVM, Lee BM (2014) Influence of upstream land use on dissolved organic matter and trihalomethane formation potential in watersheds for two different seasons. Environ Sci Pollut Res 21:7489–7500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-2667-4

Kalnay E, Cai M (2003) Impact of urbanization and land-use change on climate. Nature 423:528–532. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01649.1

Kang JH, Lee SW, Cho KH et al (2010) Linking land-use type and stream water quality using spatial data of fecal indicator bacteria and heavy metals in the Yeongsan river basin. Water Res 44:4143–4157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2010.05.009

Meybeck M (1987) Global chemical weathering of surficial rocks estimated from river dissolved loads. Am J Sci 287:401–428

Mitchell MGE, Bennett EM, Gonzalez A (2013) Linking landscape connectivity and ecosystem service provision: current knowledge and research gaps. Ecosystems 16:894–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-013-9647-2

Mondal MS, Jalal MR, Khan MSA et al (2013) Hydro-meteorological trends in southwest coastal Bangladesh: perspectives of climate change and human interventions. Am J Clim Chang 2:62–70. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajcc.2013.21007

Mutahara M, Warner JF, Wals AEJ et al (2017) Social learning for adaptive delta management: tidal river management in the Bangladesh Delta. Int J Water Resour Dev 627:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2017.1326880

Nkotagu H (1996) The groundwater geochemistry in a semi-arid, fractured crystalline basement area of Dodoma, Tanzania. J Afr Earth Sci 23:593–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-5362(97)00021-3

Nordstrom DK (2011) Hydrogeochemical processes governing the origin, transport and fate of major and trace elements from mine wastes and mineralized rock to surface waters. Appl Geochem 26:1777–1791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2011.06.002

Nunes AN, de Almeida AC, Coelho COA (2011) Impacts of land use and cover type on runoff and soil erosion in a marginal area of Portugal. Appl Geogr 31:687–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.12.006

Pielke RA, Marland G, Betts RA et al (2002) The influence of land-use change and landscape dynamics on the climate system: relevance to climate-change policy beyond the radiative effect of greenhouse gases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond A 360:1705–1719. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2002.1027

Piper AM (1944) A graphic procedure in the geochemical interpretation of water-analyses. Trans Am Geophys Union 25(6):914–928. https://doi.org/10.1029/TR025i006p00914

Poeplau C, Don A, Vesterdal L et al (2011) Temporal dynamics of soil organic carbon after land-use change in the temperate zone—carbon response functions as a model approach. Glob Chang Biol 17:2415–2427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02408.x

Pratt B, Chang H (2012) Effects of land cover, topography, and built structure on seasonal water quality at multiple spatial scales. J Haz Mat 209–210:48–58

Raghunath HM (1987) Groundwater, 2nd edn. Wiley, New Delhi

Rahman M, Das R, Hassan N et al (2014) Environmental study on water quality of Mayur River with reference to suitability for irrigation. Int J Environ Sci 4:1150–1167. https://doi.org/10.6088/ijes.2014040600006

Ramesh R, Anbu M (1996) Chemical methods for environmental analysis: water and sediment. Macmillan Publishers, London

Rogers KG, Goodbred SL, Mondal DR (2013) Monsoon sedimentation on the “abandoned” tide-influenced Ganges-Brahmaputra delta plain. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 131:297–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2013.07.014

Rothwell JJ, Dise NB, Taylor KG et al (2010) A spatial and seasonal assessment of river water chemistry across North West England. Sci Total Environ 408:841–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.041

Roy MK, Datta DK, Adhikari DK et al (2005) Geology of the Khulna City Corporation. J Life Earth Sci 1:57–63

Roy K, Ansari MS, Karim MR et al (2015) Irrigation water quality assessment and identification of river pollution sources in Bangladesh: implications in policy and management. J Water Resour Hydraul Eng 4:303–317. https://doi.org/10.5963/JWRHE0404001

Roy K, Gain AK, Mallick B, Vogt J (2017) Social, hydro-ecological and climatic change in the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. Reg Environ Chang 17:1895–1906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1158-9

Shen Z, Hou X, Li W, Aini G (2014) Relating landscape characteristics to non-point source pollution in a typical urbanized watershed in the municipality of Beijing. Landsc Urban Plan 123:96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.12.007

Shen Z, Hou X, Li W et al (2015) Impact of landscape pattern at multiple spatial scales on water quality: a case study in a typical urbanised watershed in China. Ecol Indic 48:417–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.08.019

Singh KP, Malik A, Mohan D, Sinha S (2004) Multivariate statistical techniques for the evaluation of spatial and temporal variations in water quality of Gomti River (India)—a case study. Water Res 38:3980–3992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2004.06.011

Stallard RF, Edmond JM (1981) Geochemistry of the Amazon 1. Precipitation chemistry and the marine contribution to the dissolved load at the time of peak discharge. J Geophys Res 86:9844–9858. https://doi.org/10.1029/JC086iC10p09844

Tang Z, Engel BA, Pijanowski BC, Lim KJ (2005) Forecasting land use change and its environmental impact at a watershed scale. J Environ Manag 76:35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.01.006

Tran CP, Bode RW, Smith AJ, Kleppel GS (2010) Land-use proximity as a basis for assessing stream water quality in New York State (USA). Ecol Indic 10:727–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2009.12.002

Valentin C, Agus F, Alamban R et al (2008) Runoff and sediment losses from 27 upland catchments in Southeast Asia: impact of rapid land use changes and conservation practices. Agric Ecosyst Environ 128:225–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2008.06.004

Villegas P, Paredes V, Betancur T, Ribeiro L (2013) Assessing the hydrochemistry of the Urabá Aquifer, Colombia by principal component analysis. J Geochem Explor 134:120–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gexplo.2013.08.011

Wayland KG, Long DT, Hyndman DW et al (2003) Identifying relationships between baseflow geochemistry and land use with synoptic sampling and R-mode factor analysis. J Environ Qual 32:180–190

Well JT (1995) Tide-dominated estuaries and tidal rivers. In: Perillo G (ed) Geomorphology and sedimentology of estuaries. Developments in sedimentology. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 179–205

Wilson C, Weng Q (2010) Assessing surface water quality and its relation with urban land cover changes in the Lake Calumet Area, Greater Chicago. Environ Manag 45:1096–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-010-9482-6

Yang L, Hong H, Guo W et al (2012) Effects of changing land use on dissolved organic matter in a subtropical river watershed, southeast China. Reg Environ Chang 12:145–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-011-0250-9

Yu S, Xu Z, Wu W, Zuo D (2016) Effect of land use types on stream water quality under seasonal variation and topographic characteristics in the Wei River basin, China. Ecol Indic 60:202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.06.029

Zhang W, Ruan X, Zheng J et al (2010) Long-term change in tidal dynamics and its cause in the Pearl River Delta, China. Geomorphology 120:209–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2010.03.031

Zhang T, Zhang X, Xia D, Liu Y (2014) An analysis of land use change dynamics and its impacts on hydrological processes in the Jialing River Basin. Water 6:3758–3782. https://doi.org/10.3390/w6123758

Zhou T, Wu J, Peng S (2012) Assessing the effects of landscape pattern on river water quality at multiple scales: a case study of the Dongjiang River watershed, China. Ecol Indic 23:166–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.03.013

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the project titled “Water Security in Peri-Urban South Asia: Adapting to climate change and urbanization” funded by IDRC, Canada. We thank Mr. Shankar Kumar Das for their laboratory assistance. We also like to acknowledge Mr. Kazi Rifat Ahmed for his assistance in preparing the map used in this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KR: Planned and managed the study, made interpretations and authored the manuscript: MRK, FA, MSI and KA: Took part in planning process, did field work and laboratory analysis, assisted in writing manuscript; MMR, DKD and MSAK: Involved in planning process, reviewed and commented on manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Roy, K., Karim, M.R., Akter, F. et al. Hydrochemistry, water quality and land use signatures in an ephemeral tidal river: implications in water management in the southwestern coastal region of Bangladesh. Appl Water Sci 8, 78 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-018-0706-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-018-0706-x