Abstract

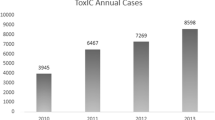

In 2010, the American College of Medical Toxicology established its Case Registry, the Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC). ToxIC is a prospective registry, which exclusively compiles suspected and confirmed toxic exposure cases cared for at the bedside by medical toxicologists at its participating sites. The Registry aims to fulfill two important gaps in the field: a real-time toxicosurveillance system to identify current poisoning trends and a powerful research tool in toxicology. ToxIC allows extraction of information from medical records making it the most robust multicenter database on chemical toxicities in existence. All cases seen by medical toxicologists at participating institutions were entered in a database. Information characterizing patients entered in 2011 was tabulated. 2010 data was also included so that cumulative total numbers could be described as well. The current report is a summary of the data collected in 2011 in comparison to 2010 entries and also includes cumulative data through December 31st, 2011. During 2011, 28 sites with 49 specific institutions contributed a total of 6,456 cases to the Registry. The total number of cases entered into the registry at the end of 2011 was 10,392. Emergency departments remained the most common source of consultations in 2011, accounting for 53 % of cases. The most common reason for consultation was for pharmaceutical overdoses, which occurred in 48 % of patients, including intentional (37 %) and unintentional (11 %) exposures. The most common classes of agents were sedative–hypnotics (1,492 entries in 23 % of cases), non-opioid analgesics (1,368 cases in 21 % of cases), opioids (17 %), antidepressants (16 %), stimulants/sympathomimetics (12 %), and ethanol (8 %). N-acetylcysteine was the most commonly administered antidote during 2011, similar to 2010, followed by the opioid antagonist naloxone, sodium bicarbonate, physostigmine and flumazenil. Anti-crotalid Fab fragments (CroFab) were administered in 106 out of 131 cases in which an envenomation occurred. There were 35 deaths recorded in the Registry during 2011. The most common associated agents, including when reported as sole agent or in combination with other agents, were opioids and analgesics (acetaminophen, aspirin, NSAIDS) with ten and eight deaths, respectively. Oxycodone was reported in six of the ten opioid-related deaths and heroin in three. Acetaminophen was the most common single agent reported overall being identified in all eight of the death cases attributed to analgesics. There were significant trends identified during 2011. Cases involving designer drugs including psychoactive bath salts and synthetic cannabinoids increased substantially from 2010 to 2011. The psychoactive bath salts were responsible for a large increase in stimulant/sympathomimetic-related cases reported to the Registry in 2011 with overall numbers doubling from 6 % of all Registry entries in 2010 to 12 % in 2011. Entries involving psychoactive drugs of abuse also increased twofold from 2010 to 2011 jumping 3 to 6 %, primarily due to increasing frequency of synthetic cannabinoid (“K2”) related intoxications as 2011 progressed. The 2011 Registry included over 600 ADR’s (10 % of Registry Cases) with 115 agents causing at least 2 ADR’s. This is up from only 3 % of cases (116 total cases) in 2010. The ToxIC Case Registry continues to grow. At the end of 2011, over 10,000 cases had been entered into the Registry. As demonstrated by the trends identified in psychoactive bath salt and synthetic cannabinoid reports, the Registry is a valuable toxicosurveillance and research tool. The ToxIC Registry is a unique tool for identifying and characterizing confirmed cases of significant or potential toxicity or complexity to require bedside consultation by a medical toxicologist.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) Case Registry was established in 2010 by the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) as a novel prospective toxico-surveillance and research tool. Participating sites record all cases cared for at the bedside or in clinics by medical toxicologists. Twenty-eight sites were actively contributing cases to the Registry in 2011. The Registry allows for identification and subsequent extraction and pooling of detailed clinical information from patients’ medical records across all centers. Through the use of expanded data collection on areas of particular interest the Registry serves as a source of prospective multi-center studies.

Because all cases on the Registry have had a formal consultation and care by a medical toxicologist, the cases recorded tend to be comprised of those with serious or potentially serious toxicities. A full description of the Registry has been previously published [1].

This is the second annual report and it includes comprehensive and comparative data from the first 2 years of Registry activity (2010–2011). Although data from 2010 Registry cases is included and compared to 2011 Registry cases, comprehensive information about the 2010 Registry experience is published elsewhere [2]. Total numbers of cases entered include 3,936 from 2010 and 6,456 in 2011, for a cumulative number of Registry cases of 10,392 by December 31st, 2011. The increase in the number of cases entered in 2011 occurred despite there being less sites participating overall (28 in 2011 vs. 33 in 2010). This increase is likely due to increased familiarity with the Registry and sites entering a greater percentage of their consults. The number of cases entered per site ranged from 3 to 847.

Methods

All participating centers aim to enter all of their medical toxicology consultations into the Registry. Case entry is done online using a password-protected user-friendly interface developed and maintained by ACMT and overseen by the ToxIC Steering Committee. No patient identifiers are provided on the database. Participation in the Registry is done pursuant to review by local institutional review board policies and procedures. A list of centers participating in the Registry during 2011 is provided in Table 1.

The information stored on the database includes demographic and detailed clinical data obtained through toxicology consultations on the patient’s exposure, encounter, signs, symptoms, clinical course, treatment, and disposition. For this report, consultation refers to all patient encounters whether admitted directly to a medical toxicology service on an inpatient unit or when the toxicologist served as a consultant. Outpatient and Emergency Department encounters are also referred to as consultations as long as a formal medical toxicology consultation was done.

Information about a patient encounter is collected and subsequently entered into the online data interface form. Technically, a number of fields are populated for each patient involving check offs or drop-down boxes. There are free text fields for signaling new, unusual, or sentinel cases, as well as for entry of the substances or species (i.e., envenomations) involved. More detailed queries require access to specific patient’s charts pursuant IRB approval. This is done only in the context of an approved study or as allowed by statute, such as reporting the details of an adverse drug reaction to the FDA.

During 2011 the Drug Abuse category was modified so that prescription, non-prescription, and other categories of drug abuse were recorded separately in order to identify different categories of drug abuse. Drug withdrawal syndromes were similarly modified.

For this report, a search was made of the database assessing the parameters in each field between the dates of 1 January, 2011 and 31 December, 2011. For comparative purposes, and when such data exists, the 2010 and cumulative 2010 and 2011 data are shown.

Results

Patient accrual throughout 2011 is included in Table 2. Demographic data about patients in the Registry are shown in Table 3; 69 % of consultations involved patients aged 19 to 64 years old, 26 % involved pediatric patients ages 18 years or less and 5 % involved ages >65 years old. As shown in Table 4, in 2011, just over half of the consultations came from emergency departments and 12 % of the patients were transferred from other hospitals to ToxIC sites.

In 2011, intentional pharmaceutical exposure represented the most common type of encounter in the Registry, accounting for 37 % of cases in which “exposure type” identified. This is consistent with data obtained in 2010 where 42 % of cases involved intentional pharmaceutical exposure (Table 5). Drug abuse was also a common reason for case entry in 2011. Overall, drug and alcohol abuse accounted for about approximately a quarter of all entries. The agents of abuse were fairly evenly divided between prescription and nonprescription drugs in 2010; however in 2011 prescription drug abuse became a more frequent reason for toxicology consultation than non-prescription drug abuse. Table 5 also shows the frequency of medical toxicology consultations for other reasons.

Sedative–hypnotics, with 1,492 exposures (23 % of all Registry cases), were the most common class of agents responsible for medical toxicology consultations in 2011, with clonazepam being the most frequently encountered followed by alprazolam. They surpassed non-opioid analgesics as the most common class of medications encountered during toxicology consultations in 2011. Exposure rates and Registry entries for different agent classes are included in Table 6. After sedative–hypnotics, non-opioid analgesics were reported 1,368 times (21 % of all Registry entries). Opioid analgesics were the third most common entry with 1,100 specific entries (17 %), and antidepressants were reported in 16 % of the cases.

Table 7 features specific toxidromes identified. Specific toxidromes were identified in 25 % of cases in 2010 and in 33 % of cases in 2011. Of cases with identifiable toxidromes in 2011, 653 (29 %) were sedative–hypnotic toxidrome and 407 (18 %) were anticholinergic toxidrome. The opioid toxidrome was identified in 314 (14 %) cases, 148 (6 %) cases were identified as serotonin syndrome, and 7 (<1 %) cases of neuroleptic malignant syndrome were identified in 2011.

During 2011, 35 cases involved patient deaths. These are listed in Table 8. The most common agent classes reported, either as sole agent or in combination, were opioids and non-opioid analgesics (acetaminophen, aspirin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS)) reported in ten and eight cases respectively. The most common opioids reported were oxycodone (identified in six of the ten cases) and heroin (identified in three of the ten cases, twice as a single agent). Among non-opioid analgesics, acetaminophen was the most common single agent overall, being reported in all eight deaths. Twenty-eight of the 35 death cases (78 %) were in ages 19–65. Males were reported in nearly two thirds of the deaths (21 of 35 cases). Most deaths involved multiple agents although 15 of 36 cases had only a single agent coded. Intentional exposure to pharmaceutical agents was the most common method of exposure associated with death although in the >65 age group ADR/ADE was the cause of death in two of three cases, both deaths involving cardiovascular agents. Agents were unknown or unreported in four of the death cases.

Sedative–hypnotic agents and muscle relaxants are shown in Table 9. Agents in these classes were involved in 23 % of all cases entered into ToxIC in 2011. Benzodiazepines accounted for 56 % of cases in this category. Among the benzodiazepines, the most common was clonazepam, identified in 30 % of benzodiazepine cases, followed by alprazolam in 29 %, lorazepam in 18 %, and diazepam in 9 %. Zolpidem was the most common non-benzodiazepine sedative–hypnotic drug exposure entered into ToxIC in 2011. Muscle relaxants accounted for 18 % of cases in this category, with cyclobenzaprine encountered most frequently with 8 %, followed by carisoprodol with 6 %. Barbiturates accounted for approximately 4 % of entries, with butalbital representing 55 % of all barbiturates.

Non-opioid analgesic entries for 2011 are shown in Table 10. Acetaminophen was by far the most common, entered in 70 % of all cases in this category and thus 9 % of all Registry cases in 2011. Over the lifespan of the Registry there were 11 acetaminophen-related deaths, of which 7 (64 %) occurred in females. Non-salicylate NSAIDS made up 15 % of this category in 2011, of which ibuprofen was overwhelmingly the most common. 19 % of the cases were due to salicylates, the overwhelming majority of which involved aspirin.

Table 11 shows the antidepressant agents entered into the Registry. The most frequently entered antidepressant in 2011 was bupropion in 16 % of cases. Citalopram was the next most common antidepressant with 14 % of all cases. Citalopram made up 38 % of the 371 SSRI cases in 2011. Trazodone was also common, encountered in 13 % of cases. Amitriptyline was the most common tricyclic antidepressant with 114 entries constituting 11 % of all antidepressant entries and 64 % of all tricyclic antidepressant entries in 2011.

Opioids and opiates accounted for 1,100 Registry entries in 2011 (Table 12). The most common category was the semisynthetic agents with 35 % of all opioid entries. Oxycodone was the most common of the semisynthetic agents accounting for 66 % of all semisynthetic-related cases. The synthetic agents, fentanyl, methadone, and tramadol, made up 29 % of the cases overall, of which methadone was the most common, representing 48 % of synthetic agents. The partial opioid agonist buprenorphine was identified in just fewer than 5 % of all opioid cases in 2011. Heroin was seen with higher frequency in 2011 than 2010 with 134 specific entries (12.2 % of all opioid entries) in 2011 compared to 61 (9.9 %) in 2010. The use of opioid antagonists is also shown in Table 12.

Table 13 shows the antihistamine/anticholinergic agents; 549 cases were included in this category in 2011. Diphenhydramine was the most common agent, reported in 54 % of the cases. The second most common agent was hydroxyzine with 13 %.

Cardiovascular agents were reported in 631 cases and are listed in Table 14. The most common categories of cardiovascular medications were the beta-blockers (21 %) and calcium-channel antagonists (19 %). Metoprolol was the most common beta blocker, accounting for 47 % of all beta blocker entries. Propranolol and atenolol each comprised approximately 20 % of beta-blocker entries. The most common calcium channel antagonist was amlodipine, comprising 40 % of these entries. Verapamil and diltiazem comprised another 28 and 22 % of cases, respectively. The most common statin was simvastatin comprising 56 % of the statin cases. Hydrochlorothiazide was the most common diuretic encountered.

Table 15 shows agents reported as stimulants or sympathomimetics. There was a large increase in this class of drugs from 2010 to 2011, primarily due to increased numbers of designer amphetamines including mephedrone, methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and other drugs sold as “psychoactive bath salts”. Mephedrone, MDPV, and “other” psychoactive bath salts were reported in a total of 111 cases (14 %) in 2011 compared to only once in 2010. Despite these increases in designer drugs, cocaine remains most common sympathomimetic or stimulant substance, accounting for 31 % of cases reported in this category in 2011. Amphetamine and methamphetamine combined accounted for 27 % of cases, caffeine was reported in 9 % of cases, and methylphenidate in 4 % of cases.

Cases classified as involving psychoactive drugs of abuse are shown in Table 16. Marijuana was the most frequent entry in this category in 2011, with 123 cases representing 34 % of all entries in this group. Although synthetic cannabinoids showed a greater than threefold increase from 11 cases in 2010 to 40 cases in 2011, the increase in marijuana entries was even greater, from 27 to 123 cases. Dextromethorphan was the next most common, representing 33 % of cases in the psychoactive category. Phencyclidine was reported about half as often as dextromethorphan. Salvia divinorum, not reported in 2010, appears in the database 4 times in 2011.

Table 17 shows the number of cases involving ethanol. In 2011, there were a total of 580 ethanol cases reported. This compares to 371 cases in 2010.

Table 18 shows the antipsychotic exposures. The atypical antipsychotics were overwhelmingly the most common type of antipsychotics reported. Quetiapine was the most frequently reported comprising 44 % of all antipsychotic medication cases. Chlorpromazine was the most commonly reported “first generation” phenothiazine antipsychotic with 14 cases (2 %). Haloperidol was the only butyrophenone entered and it was included in 36 cases (4 %).

Lithium was listed separately from the antipsychotics. One hundred cases involving lithium were reported in 2011 compared to 78 cases in 2010 (Table 19).

Table 20 shows caustic agent entries. Acids make up 27 % of this group with hydrochloric acid being the most common. Bases including sodium hydroxide and sodium hypochlorite accounted for 20 % each in this category in 2011.

Table 21 shows non-ethanol alcohols (methanol and isopropyl alcohol), ethylene glycol, glycol ethers, and similar agents. Ethylene glycol was the most common agent included in this category in 2011 followed by isopropyl alcohol, methanol, and acetone.

Table 22 includes anticonvulsant case entries. The most common anticonvulsants reported were phenytoin, valproic acid, and lamotrigine.

Snakebites make up the majority of the envenomation cases (Table 23). Rattlesnakes were the most common type of envenomation in 2011 with 59 cases, most of them by unidentified rattlesnakes. 41 envenomations were reportedly due to copperhead bites. Scorpions accounted for 21 envenomations, and the Brown Recluse was the most commonly implicated spider with 19 cases.

Diabetic agents are shown in Table 24 with sulfonylureas (37 %), metformin (26 %), and insulin (30 %) being the most common medication types reported.

Table 25 includes cases involving hydrocarbons; 67 cases of hydrocarbon exposures were reported in 2011. The most commonly reported hydrocarbons included methane, tetrachloroethylene, methylene chloride, gasoline and kerosene.

Table 26 shows the number of cases involving metals and metalloids. A total of 322 entries were included in this category in 2011 with iron reported most frequently (15 %), followed by lead (14 %), chromium (13 %), cobalt (13 %), arsenic (10 %), cadmium (8 %), mercury (8 %), and selenium (8 %).

Table 27 shows cases involving gas, vapors dust, and irritant agents. Carbon monoxide, responsible for several deaths in 2011, accounts for 130 of 169 cases in this category.

Table 28 shows cases involving gastrointestinal (GI) agents including proton pump inhibitors, antacids and other GI agents. Table 29 shows pulmonary agent exposures of which guaifenesin was the most common. Additional tables are: Table 30 endocrine agents, Table 31 chemotherapeutic agents, Table 32 antimicrobial agents, Table 33 herbal and dietary supplements, and Table 34 plants, fungi, and mold entries. Household products were not listed separately in a table as most agents were included as specific names. The majority of the agents included detergents and cleaning agents.

Additional, Non-agent Tables

Adverse Drug Reaction related consultations increased in 2011; 115 specific agents were identified at least twice in ADRs during 2011. As many ADRs involved several agents or were the result of a combination of medications, when each medication was counted separately there were 603 specific instances of a medication contributing to an ADR in 2011. The total number of separate ADR cases in 2011, however, was 229.

Lithium was the most frequent agent involved in an ADR (24 cases). Digoxin, acetaminophen, trazodone, citalopram, quetiapine and oxycodone are also common with >12 ADR cases during 2011. Agents with at least two entries documented involving ADRs are shown in Table 35.

Antidotes used are shown in Table 36. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was the most frequently reported antidote administered in 2011 making up 30 % of all antidote entries. Naloxone was the next most frequently used (19 %), followed by sodium bicarbonate (12 %), physostigmine (9 %), and flumazenil (6 %). Antivenom was administered in 131 cases. CroFab, used for crotaline snake bites, was the most common antivenom administered and accounted for 80 % of the cases in which antivenom was used. The other antivenoms used include other snake antivenom (not CroFab) in 5 cases, scorpion antivenom in 18 cases, and spider antivenom in 2 cases. Hyperinsulinemia/euglycemia therapy and intravenous lipid emulsion, two relatively new and controversial antidotal therapies, represented a small percentage of this category with 28 (1 %) and 20 (<1 %) administrations recorded, respectively.

Pharmacological support was documented in 1,661 cases. The majority (73 %) received benzodiazepines. Antipsychotics were administered in 9 % and anticonvulsants in 5 %. Dextrose (>5 % glucose) was administered in 4 %. Additional pharmacologic was reported infrequently.

The most common form of non-pharmacologic support was intubation and ventilator management being reported in 648 entries. Hyperbaric oxygen was reported in only 48 cases, cardiopulmonary resuscitation in 4, cardioversion in 4, and ECHMO once.

Very few patients received GI decontamination. Activated charcoal was entered only 285 times, whole bowel irrigation 49 times and gastric lavage 18 times. GI decontamination was documented in just over 5 % of all Registry cases.

Extracorporeal treatment in poisoning was also rare with 109 patients receiving hemodialysis. Continuous renal replacement therapy was performed in 28 cases, exchange transfusion in 5 cases. Urinary alkalinization was documented 52 times and multi-dose activated charcoal was given 18 times.

Discussion

The ACMT ToxIC Registry continues to develop as 2011 began the second year of data collection. Over 10,000 cases had been entered onto the Registry by the end of 2011. In addition to ongoing development and enhancement of the Registry infrastructure many accomplishments occurred and initiatives were developed. The Registry continues to grow in terms of publication and research applications.

A number of interesting trends are immediately evident looking at these data. In 2011, sedative hypnotics (particularly benzodiazepines), with nearly 1,500 cases, emerged as the most common agents provoking a medial toxicology consultation. These numbers, and the 1-year time period, are both too small to postulate the existence of a developing trend. Nevertheless, this is an area that warrants continued toxicosurveillance by the Registry and by other relevant toxicosurveillance systems. That this may indeed represent a trend is suggested by the fact that the sedative–hypnotic toxidrome was the most frequently encountered of all toxidromes. Much of the current concerns about prescription drug abuse have centered on opioids, and while opioids are certainly of greater concern in regards to morbidity and mortality related to overdose, the data reported herein suggest that emphasis should also be placed on the sedative hypnotics. Clonazepam was the most common sedative hypnotic reported.

Our data also suggest that while medication abuse is a major problem, restricting our concerns to prescription drug abuse fails to acknowledge the major role of OTC agents. Dextromethorphan, readily available over-the-counter, was shown to be one of the most commonly abused psychoactive substances. Modifications to the Registry data entry form will allow for better identification and surveillance involving drugs of abuse.

Oxycodone was the most common opioid medication encountered. There appeared to be an increase in the encounters involving heroin over the last two years, from 9.9 % of all opioid cases in 2010 to 12.2 % in 2011. There is concern about the reformulation of oxycodone to a preparation that is difficult to convert illicitly to a parenteral form causing an increase in heroin use. It is too early, however, to conclude that this is the reason for the increase in heroin cases the medical toxicology community is encountering. This too is an area of continued toxicosurveillance by the Registry.

The data in Table 15 demonstrates that illicit psychostimulants are a growing area of toxicologic morbidity. This appears to be driven by the growing number of cases of designer amphetamines. Agents in the psychoactive bath salts category increased dramatically from 2010 to 2011. The specific agents and the syndromes they engender is clearly a dynamic area and we expect that the multi-center nature of the Registry will allow it to play a vital role in identifying these newly emerging agents and characterizing their syndromes. Similar to the Registry experience with psychoactive amphetamines, there was a greater than threefold increase in the frequency of encounters with synthetic cannabinoids. Nevertheless, cocaine remained the most commonly encountered psychostimulant, comprising approximately 1/3 of the cases in this category over both 2010 and 2011.

The data reported herein is subject to several important limitations. The numbers and trends should not be taken as representative of the use of these agents in the general population. These data reflect only those cases cared for by medical toxicologists making it probable that they represent cases where there was likely to be significant morbidity. Cases with little or no clinical effect are probably under-represented in the Registry. As a result, the Registry is more of a marker of significant toxicities than it is of general population exposures.

A second limitation is that the history of exposure in most patients is either self-reported or comes from a third party. This raises the potential for inaccurate reporting, and is a limitation of any data set like this one.

Quality assurance for data entered into the Registry is currently the responsibility of the individual reporting sites. The data given here represent those that were reported. The Registry has initiated a quality assurance program that will provide a secondary level of monitoring the data. There may, however, be some data that is incompletely reported. To the extent that this may be the case it is most likely the outcome data that may be incomplete. Currently, the default outcome is that the patient survived without sequelae. If a death occurs after the patient has been entered in the registry it is the responsibility of the site caring for that patient to edit the record to reflect this outcome. Registry guidelines and site responsibilities have recently been strengthened reinforcing the mandatory nature of recording outcomes. This should make the possibility of incomplete data reporting less likely in subsequent years.

References

Wax PM, Kleinschmidt KC, Brent J (2011) The Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) Registry. J Med Toxicol 7(4):259–265

Brent J et al (2011) The Toxicology Investigators Consortium Case Registry—the 2010 experience. J Med Toxicol 7(4):266–276

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project comes from the American College of Medical Toxicology (see Appendix).

Conflicts of interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the staff at the American College of Medical Toxicology for supporting the ToxIC Registry project.

We very much appreciate the contributions to the Registry from each of the ToxIC sites. The following is a list of the principle coordinators from each site.

Boston, MA

Michele Burns-Ewald, MD

Charlotte, NC

Michael Beuhler, MD

Dallas, TX

Kurt Kleinschmidt, MD

Paul Wax, MD

Denver, CO

Jeffrey Brent, MD

Kennon Heard, MD

Evanston, IL

Jerold Leikin, MD

Grand Rapids, MI

Bradley Riley, MD

Bryan Judge, MD

Harrisburg, PA

J. Ward Donovan, MD

Hartford, CT

Charles McKay, MD

Haifa, Israel

Yedidia Bentur, MD

Indianapolis, IN

Blake Froberg, MD

Daniel Rusyniak, MD

Kansas City, MO

Gary Wasserman, DO

Jennifer Lowry, MD

D. Adam Algren, MD

Manhasset, NY

Mark Su, MD

Milwaukee, WI

David Gummin, MD

Mark Kostic, MD

New York, NY (Mt Sinai)

Stephanie Hernandez, MD

Alex Manini, MD

New York, NY (NYU)

Silas Smith, MD

Lewis Nelson, MD

New Brunswick, NJ

Ann-Jeanette Geib, MD

Newark, NJ

Steven Marcus, MD

Omaha, NE

Ronald Kirschner, MD

Portland, OR

Nathaneal McKeown, DO

Phoenix, AZ

Michael Levine, MD

Anne-Michelle Ruha, MD

Pittsburgh, PA

Anthony Pizon, MD

Richmond, VA

Brandon Wills, DO

Rochester, NY

Timothy Wiegand, MD

Rachel Gorodetsky, PharmD

San Antonio, TX

Shawn Varney, MD

Vikhyat Bebarta, MD

San Francisco, CA

Craig Smollin, MD

St. Paul, MN

Samuel Stellpflug, MD

Kristin Engebretsen, PharmD

Toronto, Canada

Yaron Finkelstein, MD

Worcester, MA

Sean Rhyee, MD

Steven Bird, MD

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wiegand, T.J., Wax, P.M., Schwartz, T. et al. The Toxicology Investigators Consortium Case Registry—The 2011 Experience. J. Med. Toxicol. 8, 360–377 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-012-0264-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-012-0264-9