Abstract

The rapid spread of the coronavirus virus (COVID-19) has been responsible for massive global impacts on the lives of children, families and communities. It is important to document these effects for the Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) sector. This report focuses on the Asia-Pacific region and ECEC sector, given limited regional studies on the impact of COVID-19 on early childhood education. It draws attention to the effects of the pandemic across five member countries of the Organisation Mondiale pour l’ Education Préscolaire (OMEP)—Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Thailand. The authors describe initial responses to control the spread of the pandemic in each national context and identify socio-political factors that enable broad understandings of national responses to COVID-19. In relation to the ECEC sector, responses are discussed in terms of cultural differences, economic issues, educational and professional concerns and educator wellbeing. While important government actions have rightly focused on virus suppression, it also remains important to maintain attention on the rights of children to ensure that the health crisis does not also become a child’s rights crisis and that sufficient attention is given to children’s safety and wellbeing.

Résumé

La propagation rapide du virus coronavirus (COVID-19) a eu un impact mondial massif sur la vie des enfants, des familles et des communautés. Il est important de documenter ses effets sur les secteur de l’éducation et des soins à la petite enfance (ECEC). Ce rapport se consacre à la région Asie-Pacifique et aux secteur de l’ECEC, compte tenu du nombre limité d’études régionales sur l’impact de la COVID-19 sur l’éducation de la petite enfance. Cet report se centre sur les effets de la pandémie dans cinq pays membres de l’Organization mondiale pour l’éducation préscolaire (OMEP): Australie, Chine, Corée, Japon et Thaïlande. Les auteurs décrivent les premières réponses en vue de maîtriser la propagation de la pandémie dans chaque contexte national et ils identifient des facteurs sociopolitiques permettant une vaste compréhension des réponses nationales à la COVID-19. En ce qui concerne les secteur de l’ECEC, les réponses sont examinées sous l’aspect des différences culturelles, des questions économiques, des préoccupations éducatives et professionnelles ainsi que du bien-être des éducateurs. Si d’importantes actions gouvernementales se sont concentrées à juste titre sur la suppression du virus, il reste aussi important de maintenir l’attention sur les droits des enfants afin de s’assurer que cette crise sanitaire ne devienne pas aussi une crise des droits de l’enfant, et qu’une attention suffisante soit accordée à la sécurité et au bien-être des enfants.

Resumen

La rápida propagación del virus de coronavirus (COVID-19) ha sido responsable de un impacto global masivo en las vidas de niños, familias y comunidades. Es importante documentar sus efectos en el sector de Educación y Cuidado Preescolar. Este informe se enfoca en la región del Pacífico Asiático y el sector de educación y cuidado preescolar. El presente artículo se enfoca en los efectos de la pandemia en cinco países pertenecientes a la Organización Mundial para la Educación Preescolar (OMEP): Australia, China, Japón, Corea y Tailandia. Los autores describen respuestas iniciales para controlar la propagación de la pandemia en cada contexto nacional e identificar los factores sociopolíticos que permitan una mayor comprensión de las respuestas nacionales a COVID-19. Con relación a el sector de Educación y Cuidado Preescolar, las repuestas se discutieron en términos de diferencias culturales, problemas económicos, problemáticas educativas y profesionales, y bienestar de los educadores. Aunque las principales acciones gubernamentales se han concentrado, como debe ser, en la supresión del virus, también resulta importante no perder de vista los derechos de los niños para garantizar que la crisis sanitaria no se convierta también en una crisis a los derechos de los niños y que se preste suficiente atención a su seguridad y bienestar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed the most significant global public health risk since the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 (Greenstone and Nigam 2020). It has necessitated many changes in our daily lives. Such practices as social distancing, limitations on size of social gatherings and quarantine restrictions limiting movement of people within and across national borders have become the norm across countries. When the pandemic first began to spread, many people thought it would soon pass if they kept social distance, washed their hands frequently and put on masks. However, as global infection rates soared into millions, statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated it would be difficult for daily life to return completely to what it was in a pre-COVID-19 world (WHO 2020). This report provides accounts from five countries in the Asia-Pacific region about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) sector in each country.

As news of rising numbers of COVID-19 infections and the death toll increased worldwide, many countries have adopted new policies for management of health risks, especially in parts of south-east Asia where some of the first reported deaths from the virus were confirmed. The five OMEP Asia-Pacific member countries discussed in this report were initially effective in managing the spread of the virus. Rapid responses including policies on social distancing, mask-wearing and several city-wide lockdown policies reduced the rate of transmission. In China, a city-wide lockdown in the city of Wuhan was enforced, whereas, in Korea, policy-makers undertook fast action by operationalizing technology-based, contact tracing systems and other aggressive measures for virus detection. Thailand declared a state of emergency and enforced curfews on people to stay at home. Korea and Thailand were successful in managing the spread of the virus within a short period of time. Japan also declared a state of emergency and effectively controlled the spread of the virus without enforced lockdown requirements. Australia introduced international and national travel bans along with social distancing measures in public places.

The policy strategies used in Korea, Thailand, Japan and Australia managed to keep the initial spread of the infection quite low compared to the USA and many other European countries. Yet, despite the introduction of effective public health measures, some of the most vulnerable members of society faced higher risks, including the elderly and health care workers. Children who received early education and care within group settings and the professionals who regularly work with these children also faced risks. The accounts presented in this paper identify the complexities and challenges faced in each of the countries discussed. This may provide contextual understandings for early childhood professionals across countries that can inform development of practices in early childhood services that can support the needs of children, families and staff working with young children in a post-COVID-19 world.

Throughout this report, the term early childhood education and care (ECEC) is used to refer to center-based services for children in the prior-to-school sector. This term encompasses ‘kindergartens,’ ‘preschools’ and ‘child care’ services. The term ‘educators’ are used to refer to teachers and child care center staff employed in these services.

Socio-Political Factors and Control of the Spread of COVID-19

Socio-political factors include a combination of public health measures and government policies. Understanding these factors serves to broaden our understanding of how the spread of the COVID-19 virus was managed across countries and how different strategies impacted on children, families and ECEC services.

In December 2019, China was initially affected by the sudden outbreak of COVID-19 in the city of Wuhan. By January 19, all 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions in mainland China activated a Level 1 health emergency response. This response from the highest levels of government was operationalized throughout China to prevent any further spread of COVID 19 (the State Council of China 2020). By January 23, 2020, a city-wide lockdown was enforced in Wuhan.

By mid-January, the virus had reached Thailand and had spread to Korea and Japan. By the end of January 2020, the virus had also reached Australia. Both Korea and Thailand acted swiftly to implement rapid and strict responses to contain the virus. The Korean Government policies issued three levels of warnings: Level 1 (attention); Level 2 (boundary); and Level 3 (severity) (WHO, 2020). Level 1 permitted everyday life as usual without special restriction, including the wearing of masks, but high levels of testing were initiated to effectively screen people for the virus. Level 2 enforced quarantine restrictions of infected people in isolation wards or at home. Extensive procedures for contact tracing were initiated, for example, using CCTV footage if needed. Level 3 required the entire country to be locked down. Korea’s quick response was in line with the lessons learnt from the country’s experience in managing the SARS pandemic in Korea between 2002 and 2004. This response to COVID-19 provided an example for early success to contain the spread of the virus.

Similar to Korea, the government’s response in Thailand to the outbreak was also based on surveillance and contact tracing in accordance with the 3-stage response model for the Department of Disease Control (DDC 2020). Strategies including temperature and symptom screening as well as testing for the coronavirus virus were implemented at international airports, as well as in hospitals for patients with any travel or contact history. Investigations were also performed in response to outbreak clusters. The voluntary use of an online platform, ‘Thai Chana,’ was also endorsed by the government in Thailand and has also been effective in maintaining the country’s control measures for COVID-19. This platform has assisted government to collect data on places that infected people have visited and also provided a tracing strategy to mitigate the spread of the infection.

The Japanese Government issued basic policy guidelines requesting citizens to refrain from activities in which large numbers of people would gather and to adopt ‘telework’ practices wherever possible. To prevent the further spread of infections, Japan also introduced a government slogan titled ‘Avoid the Three C’s!,’ that is, closed spaces, crowded places and close-contact settings. However, by April 16, 2020, a state of emergency was declared nationwide. Despite restricting people’s movements and other limitations on activities, Japan’s state of emergency was not a mandated lockdown. Compared to other countries, Japan’s state of emergency was entirely voluntary, and no legal restrictions were imposed.

In Australia, the spread of the virus was seemingly more gradual. The first Australian case of the outbreak was linked to a traveler from Wuhan in China. However, as the number of reported daily infections increased exponentially, doubling every three to four days, the Australian Government convened a National Cabinet, in mid-March 2020 (Burton 2020). The National Cabinet comprised the Prime Minister, as well as state and territory leaders, to coordinate decisions across all Australian jurisdictions to manage the crisis. First, travel bans were extended to individuals entering Australia from other parts of the world such as Iran, Korea and Italy. Next, tighter international border controls were implemented requiring new arrivals returning from overseas to self-isolate for 14 days. Then, all international arrivals were required to be quarantined in designated hotel facilities for 14 days. At a similar time to international border controls, the inter-state borders between states and territories within Australia were also closed.

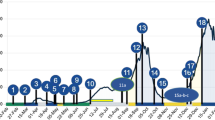

Figure 1 provides a snapshot of COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths in the five countries discussed in this report: Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Thailand and dates on initial lockdown periods in 2020 (WHO 2020).

[Source WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) from https://covid19.who.int/] at August 21, 2020]

Confirmed coronavirus cases across five East-Asian countries and lockdown periods in 2020

In all five countries, different measures were introduced by governments to mitigate the economic downturn and financial burdens as a result of citizens’ loss of employment and restricted living conditions.

In Australia, unemployment rates began to dramatically rise throughout March 2020. However, the Australian Government implemented two key economic measures: JobSeeker payments for eligible individuals seeking employment and JobKeeper payments to businesses to subsidize employee wages, keep people employed and support commercial businesses and not-for-profit organizations (Treasury, Australian Government, n.d). These payments were designed to support the Australian economy through the crisis. In China, the Central Government announced measures, on February 7, 2020, to cover all medical expenses of confirmed coronavirus patients by health insurance or provide financial compensation (Peng et al. 2020). The Central Government paid special attention to families in poverty and provided subsidies to such families, with a total of ¥156 billion until April 2020 (Zhong 2020).

Taking a different approach to China, the Japanese and Korean governments introduced cash payments per person to ease the financial burden experienced by their citizens. The Japanese government provided special cash payments of ¥100,000 for each person living in Japan, including foreign residents, and a child allowance of ¥10,000 per child. A special grant for single-parent households of ¥50,000 was also provided. In Korea, subsidies of USD$333 per person were introduced along with gift vouchers for electronic goods. Approximately 2.63 million children (about 2.09 million households) received vouchers, valued at USD$333 for each child under 7 years of age, to help parents purchase electronic resources to support their children’s home learning during the pandemic. Initially, the Thai Government allocated a relief package of $3.1billion for individuals and businesses affected by the virus. However, despite efforts to alleviate the financial burden of COVID-19, each country included in this report has experienced significant economic downturns.

Early Childhood Education and Care Contexts

Despite the implementation of key national public health and economic strategies in response to COVID-19, significant challenges also became clear for the early childhood sector. Teachers and educators of the world’s youngest children had to respond quickly to changes produced by the COVID-19 outbreak. Many early childhood services were suddenly placed at the frontline of the pandemic when they were considered as essential services to enable child care support for frontline workers who were employed in hospitals or other critical industries, which needed to continue operations through the pandemic, such as transport and food supply services. At the same time, many families withdrew their children from kindergartens/preschools and child care services or kept them at home due to lockdown restrictions. In the following section, we outline some of the challenges and similarities across countries in the availability of kindergarten, preschool and childcare services during the pandemic. We draw attention to the experiences across the ECEC sector for the five countries in the Asia-Pacific region and outline the implications for children and the early childhood profession.

Australia

Australia provides care and education for over 1.4 million children attending preschool and childcare services (Department of Education, Skills and Employment 2020). As the coronavirus threat worsened, ECEC services were required to remain open wherever possible for children. For families using these services, free child care was provided by the Australian Government (Prime Minister of Australia 2020) for more than one million working parents in order to ensure that these parents could keep working and child care services could remain viable. Children were eligible to miss up to 62 days without losing a government-funded Child Care Subsidy payment which is the main way in which the Australian Government assists all low- and middle-income families with child care fees. Services were also eligible to apply for JobKeeper payments to supplement the wages of educators.

ECEC services adjusted their daily programs to provide stable and predictable routines for children while being flexible with the nature of learning experiences provided. Creating a sense of stability in familiar environments supported children’s emotional wellbeing at a time when many children missed their friends and were aware of numerous changes in their family’s life. At the same time, social distancing rules were difficult to maintain for very young children, and to manage these concerns, educators implemented strict hygiene regimes (Early Childhood Australia 2020).

Nevertheless, educators faced challenges in the reduced contact with parents because close relationships with families are a strong characteristic of early childhood pedagogical practice. Adhering to strict hygiene rules often meant minimizing the number of parents at arrival and departure times and keeping these times as short as possible. Some services used digital sign-in devices, such as iPads, for parents to sign their children’s arrival and departure times, whereas other services used gatekeeper mechanisms to screen children’s entry to services and check temperatures upon arrival. In many instances, parent contact was limited to one parent for very short periods of time. These restrictions made maintaining close relationships with families difficult.

Wherever possible early childhood educators provided resources to support children and families who remained at home. This support was provided through online teaching and learning. Some services provided regular communication through existing secure online portals, for instance, through the use of Storypark or regular newsletters with links to online resources (e.g., NSW Government, Early Childhood Education, n.d.). The Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) expanded their educational television programs to be available nationally on a weekday basis from 10 am to 3 pm. Other online resources to support children’s play and learning at home were available from each state’s and territory’s early childhood education departments. While a range of online teaching and learning resources was freely available, the nature of these resources varied greatly across early childhood centers and the requirements specified across the different Australian states and territories.

China

China’s ECEC sector has over 60% of private ECEC services (kindergartens). The long period of closure due to the lockdown placed significant financial burden on these kindergartens. In order to help these services to manage through this difficult time, the Ministry of Education (April 15, 2020) required local governments to provide support for private kindergartens through four measures by: (1) providing fiscal subsidies; (2) reducing rent; (3) reducing taxes; and (4) providing financial support through loans. By early June, 2020, almost all kindergartens in China were open, but policies differed across regions. For instance, in Shanghai, all kindergartens were open for children by June 2, 2020 for the whole day. However, in Jilin province, kindergartens only opened over time in succession. Parents were cautious about returning their children to kindergartens, especially for those parents with younger children. As a result, the attendance rate was low, but higher attendance rates were evident for older children.

As early childhood education and care is not a part of the nine-year compulsory education system, the government did not organize online teaching and learning for early childhood education during the lockdown period. However, the China National Society for Early Childhood Education (CNSECE) established an expert team and developed guidelines focused on children’s play for families to use at home during the period when children were not attending their kindergarten service. In addition, OMEP China also collected a package of educational resources, including stories, children’s songs, video clips and instructions on different types of play activities and sent these to the Child Development Research Fund (CDRF), a non-government organization in charge of development of early childhood education in rural China. Despite the lockdown period, many kindergartens also developed different materials, held activities online and provided suggestions to encourage parent–child interactions and play, for parents to use at home. These resources included video clips of a teacher reading picture books, instructions for conducting science experiments at home, making handicrafts and providing other ideas for indoor activities. In some kindergartens, the teachers would meet children in their class online and organize these activities. In some kindergartens, especially in private kindergartens, daily opportunities were provided to parents to communicate with their child’s teacher online.

As centers reopened, educators practiced strict infection controls and arranged sufficient play activities for children to reduce any fears and anxieties and create relaxed learning environments. For instance, in Shanghai, children’s kindergarten activities were changed regularly to provide more flexible periods of time for children to pursue free-play, group and outdoor activities compared to the previously more highly structured timetable. Providing a stable schedule with shorter days and more flexibility for play supported both children and families to cope with increased levels of anxiety associated with the potential spread of the virus in their communities. As the spread of the virus appeared to ease with few COVID-19 cases reported, the program changes eased parent anxieties and supported children’s gradual return to kindergartens.

Japan

The Japanese government tried to restrict the spread of COVID-19 by school closures that continued until the lifting of the State of Emergency on May 25, 2020. Japanese policy administration for ECEC is split between education and welfare sectors. Three types of ECEC provisions are available in Japan and operate under various government departments. Kindergartens operate under the administration of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Nursery centers operate under the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) and integrated ECEC centers that provide education and child care, operate under the administration of the Cabinet Office (NIER 2020).

While nursery centers provided regular child care services during the period of school closures to meet the needs of working parents (Japanese Federation of Private Nursery Schools 2020), some local government departments requested that many nursery centers close on a temporary basis or downsize their operations. Integrated ECEC centers continued to provide educare for children of working families. With respect to kindergartens, under the requirements of the state of emergency, some local governments required all kindergartens to close with the exception of kindergartens catering for children of essential frontline workers. ECEC services for children aged 3–5 years have been provided for free since October 2019. During the period of school closures, the Japanese Government guaranteed ECEC teachers’ salaries even though kindergartens may have been closed (Cabinet Office 2019).

Through this period, numerous online and on-demand programs and resources for young children were delivered by many organizations, including TV stations, municipal boards of education and private educational bodies. The Japanese public broadcaster (NHK) opened a special COVID-19 site for children to support home education using an on-air program. The government department, MEXT, provided a one-stop information site for resources via their website, including for remote education. The early childhood education online page of MEXT also provided examples about how to play, learn and spend time at home with suggestions and advice from medical and academic associations. In Japan, some kindergartens actively utilized services and sourced online activities to use with children and parents, from businesses in the ICT industry including social networking sites. Other kindergartens preferred traditional ways of communication such as making phone calls or sending letters with handmade learning materials or picture books to children and parents. The Agency for Cultural Affairs, which is a special agency in the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and which promotes Japanese arts and culture, also requested easing of copyright restrictions for greater accessibility and usage to many resources for online education for children and families.

Supporting parents became increasingly important and teachers contacted parents directly to allay any anxieties and stress. Concerns about children’s wellbeing while they remained at home were collected by the government departments (MEXT and MHLW) to monitor the risk of child abuse. Phone-in services for adults and emergency (SOS) phone-in services for children were also available 24 h per day. Some kindergartens provided additional respite services (temporary child care for children and families with any special needs).

Educators and parents recognized the detrimental effects for children who were unable to spend time with classmates during the periods of home isolation. In a private kindergarten in Tokyo, parents reported higher levels of children’s engagement and wellbeing when online classes were available with their teachers and classmates (Musashino Higashi daiichi·daini Youchien, 2020). Feedback from parents on these classes led to the development of enjoyable online programs of gymnastics and dancing to encourage physical activities. While the longer-term effects of virtual learning through online classes are difficult to predict, the short-term effects of ‘simultaneous’ online contact for kindergarten children appeared to have been positive during the time of home isolation. However, after several months of home isolation, reports from educators indicate large differences in the quality of children’s home learning experiences. Additionally, children’s perceptions of the meaning of COVID-19 were also quite different, reflecting differences in the home learning environment.

Since June 2020, most kindergartens have resumed regular education programs while implementing strict hygiene and health measures. These measures include the use of partitions to divide spaces within rooms, new seating arrangements and a range of practices focused on greater ventilation within centers, careful hand washing, temperature checks and other health care measures. One private kindergarten association in a city near Tokyo created its own coronavirus countermeasure models for the area. This model recommended that all teachers wear masks but did not force children to do so. Educators have become much more aware of the importance of hygiene management than ever before. However, these extra tasks to disinfect surfaces and materials add significantly to educators’ workloads.

Republic of Korea

Korea’s ECEC system consists of kindergartens for children aged between three and six years and childcare centers for children from birth to 5 years. Kindergartens and child care centers are provided by either national, public or private services. For Korean kindergartens and childcare centers, the main focus during the pandemic period has been to keep the virus from spreading. When the COVID-19 outbreak first occurred, children were considered to be less likely to be infected. However, on August 21, 2020, 64 kindergarten children had been quarantined by health authorities because ten children had confirmed positive for COVID-19. If a kindergarten child tested positive for COVID-19, all kindergartens in the district were required to close for two weeks. Hence, educators employed in kindergartens became extremely aware of ways to adhere to socially distancing even during play, by avoiding group activities, minimizing the sharing of objects and maximizing the space available for play activities.

As a result of pandemic, there is a reduction in the number of children attending kindergarten every day because attendance numbers were restricted in kindergartens. Only one-third of the usual number of children were permitted to attend kindergarten each day. On average, the teacher to child ratio was 1 to 8. For those children who stayed at home, educators sent parents play materials every week along with guidelines for use. These play materials varied slightly according to each kindergarten. Online resources were also provided. Some kindergartens also uploaded guidelines on the kindergarten’s website for parents to access play resources with their children at home.

Each kindergarten educator provided a daily schedule of activities for children with online classes to be implemented with support from parents at home. However, there was no standardized format for online classes. In order to support educators and parents, the government provided a program called ‘My Kindergarten’ for 40 min per day via the public broadcasting channel, Educational Broadcasting System (EBS). The EBS programs included hygiene-related activities, hand washing and daily physical activities. Episodes demonstrated how to play with open-ended materials that could be easily found at home. The programs also included a focus on staying psychologically well. Each kindergarten linked this program into their daily schedule for online classes. However, despite the implementation of these supports, debates existed among educators and parents about whether it was appropriate to teach kindergarten students remotely.

Educators are now required to prepare lesson plans for the daily face-to-face classes as well as produce materials for online classes separately. Additionally, educators are required to communicate with parents remotely and practice quarantine restrictions when necessary. While the government-subsidized costs for hiring two people for each kindergarten for the quarantine periods, the workload for educators dramatically increased.

Another concern for educators was the reduced number of school days. Legally Korean children are required to attend kindergarten classes for 180 days. However, since the reduction in allowable attendance days, children only attend kindergarten one or two days a week. For the remaining days, online classes are available. Debates exist as to whether online kindergarten classes, delivered in homes, should be given the same recognition as kindergarten classes offered face-to-face. In order to compensate for the reduced number of face-to-face kindergarten days, the Ministry of Education has submitted a revised ‘Enforcement Decree of the Early Childhood Education Act’ to the National Assembly. Once this law is passed, superintendents of each providence can decide the number of school days with flexibility.

Thailand

In Thailand, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a major disrupter for the ECEC sector. It has led to approximately 20,000 privately-run daycare workers losing their jobs due to lockdown requirements. Approximately 800,000 kindergarten children aged between 3 and 5 years old were unable to access center meals due to the closure of Early Childhood Development Centers, while almost 7 million other children who benefit from meal programs nationwide faced additional risk as a result of food insecurity while ECEC centers remain closed. Since the centers have been forced to close, many parents have had little choice but to place their children in the care of relatives or unlicensed daycare providers, if they need to work.

The closing of educational institutions to limit social contact has resulted in many young children depending on online learning from home. However, transitioning to online learning has not been easy for many young children in Thailand. Many children and families do not have access to digital devices such as computers and tablets or the Internet, in order to access online resources for children from home. These children usually come from low-income families, who are severely affected by this transition to home learning. The financial resources to afford a computer are very low for poor households. Some parents devised their own solutions by collectively organizing part-time group care or homeschooling under the supervision of their local child development centers or schools. The experience of COVID-19 has highlighted the need for the Thai government to take the needs for linkages between technology and education very seriously. On July 1, 2020, all schools in Thailand reopened.

The Office of Basic Education in the Ministry of Education provided guidelines for three learning and teaching models to be implemented appropriately during the pandemic. These models incorporated on-site, on-air, and on-air learning and teaching and blended learning approaches could also be used. A key consideration in the planning of learning and teaching activities was appropriate design for students’ safety and social distancing requirements of 1 to 2 meters.

The Office of Health in the Ministry of Public Health also distributed guidelines about self-protection and daily practices during the pandemic for all reopened child care development centers. The guidelines provide essential information that focuses on the prevention of COVID-19 for administrators and center owners, educators and parents. At the entrance of each center, there is provision for specific child arrival and collection areas. There are also screening areas equipped with hand washing materials, as well as regulations for food handlers and cooking areas. The cleaning of bathrooms and toilets with disinfectant is completed at least twice daily. Educators maintain social distance of at least 1–2 meters apart and provide plexiglass shields for interactions between children. Educators are required to wear masks during the care and education of all children over 2 years old. Children are taught how to wear face masks and engage in strict hygiene measures. If educators have experienced either fever, coughs, sneezes or exhaustion or have returned from a COVID-19 risk zone they must remain at home. Activities for young children have been redesigned for small groups of no more than six children.

Discussion

The accounts provided from each country indicate four key issues emerging from the impact of the pandemic on the ECEC sector. These are cultural differences; economic issues; safety and psychological issues; and educational and professional issues (Bryant 2020; NSW Early Childhood Teachers, n.d.). Cultural differences explain some fundamental differences in generally accepted ways of living. Economic issues related to the level of government support provided in each country for children, families, educators and ECEC services. Safety and psychological issues relate to the increased levels of hygiene measures and the contact restrictions add to workload and stress for educators. Educational and professional issues consider the increasing inequalities for children’s learning opportunities and questions of curriculum and program priorities. The discussion focused on these four issues and their implications for the ECEC sector.

Cultural Differences

How citizens observed government restrictions to contain the spread of COVID-19 may have varied according to cultural practices in each country. For example, although Australia is one of the most multicultural countries in the world, a culture of mask-wearing is not commonplace. In contrast, many Japanese, Korean, Chinese and Thai citizens were more familiar with mask-wearing because masks are often worn in winter to prevent flu infections. Other forms of greetings across countries were also more conducive to containing the spread of the virus and required change. The cultural etiquette in Thailand is to greet partners with palms close together at chest level close their body, bowing slightly. The bow is also a cultural etiquette for greetings in Japan and Korea. Both Thai, Korean and Japanese greetings do not require physical touch in comparison to shaking hands, which is more common in China and Australia. Hence, why some countries may have been more successful in preventing the spread of COVID-19 may also relate to the nature of cultural practices.

Economic Policy Issues

The COVID-19 has caused many business activities to shrink, causing stress, anxiety and related mental health issues for many families especially for those either employed in small business enterprises, who own businesses or who are self-employed. Each country provided financial supports for families, educators and ECEC services, and the type and amount of support varied. Table 1 summarizes the types of government financial support provided for children, families and the ECEC sector during the pandemic, across the different countries.

COVID-19 has had an impact on the entire Early Childhood Education and Care sector, although it has perhaps been felt most keenly in the private sector. As child enrolments declined, many childcare services faced decisions about service closures, job losses and the need to keep only some services operational for the children of essential workers. With many private for-profit ECEC services on the brink of collapse, COVID-19 has shone a light on a range of problems for the viability of ECEC services associated with privatized service delivery in times of pandemics. In a sector that is already constrained by challenges of sustaining a qualified early childhood workforce, additional financial issues have placed great strain on educators and ECEC services. COVID-19 has raised questions about whether market-based systems are most effective for future-proofing the ECEC sector in different countries.

Safety and Psychological Issues for Educators

At the outset of the coronavirus pandemic, reports from the WHO as well as other national health organizations indicated that the number of young children infected was very low. However, as young children are still potentially carriers of infections, most countries either directed their ECEC centers to close and/or ensured that much stricter hygiene and health measures were implemented in centers. Many educators were unprepared for the range of personal and professional issues that they faced during the pandemic.

The issues included the possible high level of risk of infection in workplaces, increased workloads and increased responsibilities for children’s safety. Educators continued to implement strict hygiene practices and keep children safe in potentially unsafe environments on a daily basis. Yet, long incubation periods and sometimes mild symptoms made it difficult for educators and parents to detect and prevent virus transmission. These stressful working conditions position educators and children in risky situations and made the complexities of educators’ work more visible.

Many educators have experienced anxiety and tension due to increased risks of infection while working, including the need to commute to and from work. These tensions have taken a toll on educators’ emotional wellbeing and their mental health (Choi 2020). Moreover, decisions about which educational services would remain open and which would close have again highlighted long standing divisions between the work arrangements for educators in child care services compared to teachers in schools. Compared to their colleagues in schools, educators in child care have felt less valued and more vulnerable (Quinones et al. 2020).

Educational and Professional Issues

Although across the counties discussed, a range of ECEC services remained open during the pandemic, for example, for essential workers, many other parents at home with their children were required to support their children’s home learning.

Despite the potential opportunities offered by online learning, access to these opportunities was dependent on parents’ knowledge of technology, their capacity to access online resources and their availability to devote time to such activities. Some families had limited access to technological devices or reliable Internet connections. For example, in many geographically remote Australian towns, Internet connections can be unreliable leaving these areas less able to access online teaching and learning activities. Moreover, compared to countries worldwide, only 21% of Thai households have computers, which is lower than the global average of 49%. In Japan, over 50% of children aged 3 years and over 68% of children aged 6 years use the Internet.

In the countries that are the focus in this analysis, some children may have received excellent early learning support at home, whereas others may have been disadvantaged because of the lack of access to digital devices or Internet connectivity. Arguably, the COVID-19 pandemic has made the digital divide more visible across, and within, these East-Asian countries. Questions remain about the place of virtual learning, through the use of ICT, as either a temporary introduction in ECEC or as the basis for an expansion of early childhood pedagogies that incorporating more strongly digital media. More quality research is needed about how ICT and digital media can complement play-based learning approaches in early childhood curriculum development and delivery. However, it is important not to deepen existing inequalities through lack of access to digital devices or Internet connectivity. This is a key challenge for the future across ECEC sectors in different countries.

Play-based pedagogy has been restricted during the current pandemic. Closer examination is needed on the nature of pedagogical practices that support learning most relevant and engaging for children in the current environment when various health risks have to be taken into account as educators plan play-based activities. How can educators build quality interactions with children as well as ensuring some level of physical contact in many situations when a sense of security for young children is necessary, without posing unnecessary risks to children’s health? What are the most important routines and activities that support children’s learning through play when access to a variety of materials, contact with natural resources and collaboration with peers may be limited? It remains necessary for educators to reflect carefully about the aspects of ECEC curriculum and the pedagogical strategies which they see as priorities in designing learning opportunities which will engage children and bring a sense of enjoyment and accomplishment.

Conclusion

As the pandemic continues to evolve and spread globally across 2020, availability and access to a vaccine still remain somewhat uncertain. Concerns are raised about the rights of children and educators to access both safe and high-quality ECEC sites and services. A recent position paper by the World Organization for Early Childhood Education (OMEP 2020), Early Childhood Education and Care in the Time of COVID‑19, raised concerns that the pandemic may erode living standards and services to families, as well as opportunities for early education for children living in vulnerable circumstances. Other common concerns for children and their educators include the number of ECEC services that have remained operational across countries due to the coronavirus pandemic, restricting play opportunities for children, limiting social contact between children and increasing inequities in children’s access to learning resources and early education (Pramling et al. 2020). We contend that economic problems as a result of the pandemic threaten the viability and sustainability of ECEC services across many countries.

While governments’ actions have rightly focused on virus suppression, supports for children and families should also remain of highest priority, given financial strains on families, as well as emotional and other stressors. These issues raise concerns for children and educators safety and wellbeing. As the position paper from the World Organization for Early Childhood Education (2020) noted it is time to advocate for state parties to: “… build comprehensive solutions with intersectoral articulations to accompany and support families, protecting children’s right to health, food security, recreation and play, vital for their growth and development …” (p. 121).

References

Bryant, L. (2020). Surviving not thriving in early education and care [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_YS7h3QBOHk.

Burton, T. (2020). National cabinet creates a new federal model. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/national-cabinet-creates-a-new-federal-model-20200318-p54bar

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. (2019). Learn about free early childhood education and care. Tokyo: Government of Japan, https://www.youhomushouka.go.jp/about/en/.

Choi, Y. (2020). A study on the emotional experiences of child care teachers and changes in their daily routine in centers after COVID-19. Korean Journal of Early Childhood Education. https://doi.org/10.15409/riece.2020.22.1.12.

Department of Disease Control (2020). Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19). Bangkok, Thailand: Ministry of Public Health. https://ddc.moph.go.th/viralpneumonia/eng/index.php

Department of Education, Skills and Employment (2020). Child care data for December quarter 2019. Canberra, ACT: Australian government. https://www.education.gov.au/child-care-australia-report-december-quarter-2019.

Early Childhood Australia [ECA]. (2020). ECA response: COVID-19. Canberra, ACT: Early Childhood Australia. http://www.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/COVID-19-ECEC-Health-and-Hygiene-Members-Summary_UPDATE_29052020_Typeset.pdf.

Greenstone, M., & Nigam, V. (2020). Does social distancing matter? Working paper no. 2020-26. Becker Friedman Institute. Chicago, MI. University of Chicago. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3561244

Japanese Federation of Private Nursery Schools (2020). A report on COVID-19 (in Japanese). Tokyo: http://www.zenshihoren.or.jp/about/diagram/tyousa.html.

Ministry of Education, General Office. (2020). The notification on supporting private kindergartens during the COVID 19 control period. http://www.gdmbjy.cn/html/2020/jjy_0426/4273.html.

Musashino Higashi daiichi daini Youchien. (2020). Onrain kaigi tsūru o tsukatta `kurasu no atsumari’/”Class gathering” using online meeting tools. Tokyo. https://www.musashino-higashi.org/newinfo/uppdf/20200511124638.pdf (in Japanese).

National Institute for Educational Policy Research [NIER]. (2020) Information and resources on ECEC in midst of COVID-19. Tokyo. https://www.nier.go.jp/English/youji_kyouiku_kenkyuu_center/Links-to-Relevant.html.

NSW Government. (n.d). NSW Early Childhood Teachers. Home [Facebook page]. Sydney: Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/302549249900903/about.

OMEP Executive Committee (2020). OMEP Position paper: Early childhood education and care in the time of COVID-19. International Journal of Early Childhood. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00273-5.

Peng, F. J., Tu, L., Yang, Y. S., et al. (2020). Management and treatment of COVID-19: The Chinese experience. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 36, 915–930.

Pramling, S. I., Wagner, J. T., & Eriksen Ødegaard, E. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic and lessons learned in preschools in Norway, Sweden and the United States: OMEP policy forum. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52(2), 129–144.

Prime Minister of Australia (2020). Early childhood education and care relief package. Media release. Canberra, ACT: Dept of Prime Minister Department, Australian Government Retrieved from https://www.pm.gov.au/media/early-childhood-education-and-care-relief-package.

Quinones, G., Barnes, M., & Berger, E. (2020). The emotional toll of COVID-19 among early childhood educators. The Sector. https://thesector.com.au/2020/08/06/the-emotional-toll-of-covid-19-among-early-childhood-educators/

The State Council of China. (2020). The latest information on COVID http://english.www.gov.cn/state_council/ministries/2017/02/07/content_281475561576942.htm.

World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Weekly epidemiological update and weekly operational update. Geneva Switzerland. WHO. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/.

NSW Government Early childhood education. (n.d.). Learning from home. Sydney: NSW Government. https://education.nsw.gov.au/early-childhood-education/information-for-parents-and-carers/learning-from-home.

Treasury, Australian Government. (n.d.). Economic response to the Coronavirus. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government. https://treasury.gov.au/coronavirus.

Zhong, D. (2020). Respond calmly and move forward-China’s economy responds to the impact of the new crown pneumonia epidemic. Economic Daily. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-07/27/content_5530242.htm.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of OMEP Board members from Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Thailand and colleagues for sharing their insights during the first six months of the coronavirus pandemic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Park, E., Logan, H., Zhang, L. et al. Responses to Coronavirus Pandemic in Early Childhood Services Across Five Countries in the Asia-Pacific Region: OMEP Policy Forum. IJEC 52, 249–266 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00278-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00278-0