Abstract

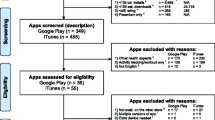

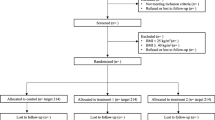

The use of online communities and websites for health information has proliferated along with the use of mobile apps for managing health behaviors such as diet and exercise. The scarce evidence available to date suggests that users of these websites and apps differ in significant ways from non-users but most data come from US- and UK-based populations. In this study, we recruited users of nutrition, weight management, and fitness-oriented websites in the Czech Republic to better understand who uses mobile apps and who does not, including user sociodemographic and psychological profiles. Respondents aged 13–39 provided information on app use through an online survey (n = 669; M age = 24.06, SD = 5.23; 84% female). Among users interested in health topics, respondents using apps for managing nutrition, weight, and fitness (n = 403, 60%) were more often female, reported more frequent smartphone use, and more expert phone skills. In logistic regression models, controlling for sociodemographics, web, and phone activity, mHealth app use was predicted by levels of excessive exercise (OR 1.346, 95% CI 1.061–1.707, p < .01). Among app users, we found differences in types of apps used by gender, age, and weight status. Controlling for sociodemographics and web and phone use, drive for thinness predicted the frequency of use of apps for healthy eating (β = 0.14, p < .05), keeping a diet (β = 0.27, p < .001), and losing weight (β = 0.33, p < .001), whereas excessive exercise predicted the use of apps for keeping a diet (β = 0.18, p < .01), losing weight (β = 0.12, p < .05), and managing sport/exercise (β = 0.28, p < .001). Sensation seeking was negatively associated with the frequency of use of apps for maintaining weight (β = − 0.13, p < .05). These data unveil the user characteristics of mHealth app users from nutrition, weight management, and fitness websites, helping inform subsequent design of mHealth apps and mobile intervention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pew. PEW Research Center/CHCF Health Survey. 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/02/12/the-internet-and-health/.

European Commission D-G for C, Networks C and T. Flash Eurobarometer 404 “European Citizens’ Digital Health Literacy.” 2014. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_404_sum_en.pdf.

Kontos E, Blake KD, Chou W-YS, Prestin A. Predictors of eHealth usage: insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. J Med Internet Res. 2014; 16(7):e172. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3117.

Graham AL, Papandonatos GD, Erar B, Stanton CA. Use of an online smoking cessation community promotes abstinence: results of propensity score weighting. Health Psychol. 2015; 34(Suppl):1286–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000278.

Leist AK. Social media use of older adults: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2013; 59(4):378–84. https://doi.org/10.1159/000346818.

Antypas K, Wangberg SC. An internet- and mobile-based tailored intervention to enhance maintenance of physical activity after cardiac rehabilitation: short-term results of a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014; 16(3):78–95. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3132.

Statista. Worldwide Mobile App Revenues 2020|Statistic. https://www.statista.com/statistics/269025/worldwide-mobile-app-revenue-forecast/.

Yang C-H, Maher JP, Conroy DE. Implementation of behavior change techniques in mobile applications for physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 48(4):452–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.010.

Conroy DE, Yang C-H, Maher JP. Behavior change techniques in top-ranked mobile apps for physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2014; 46(6):649–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.010.

Middelweerd A, Mollee JS, van der Wal CN, Brug J, Te Velde SJ. Apps to promote physical activity among adults: a review and content analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014; 11:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-014-0097-9.

Pew Research Center. Few Americans Track Their Weight, Diet or Exercise Online | Pew Research Center. 2014. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/08/few-americans-track-their-weight-diet-or-exercise-online/.

Purcell K. Pew Internet Research. Half of adult cell phone owners have apps on their phones Americans’ appetite for apps continues to grow. 2011. http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2011/PIP_Apps-Update-2011.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2016.¨.

European Commission. Green Paper on Mobile Health (“mHealth”); 2014. file:///C:/Users/SterianiElavsky/Downloads/GreenPaperonmobilehealth (1).pdf.

Schnall R, Rojas M, Bakken S, Brown W, Carballo-Dieguez A, Carry M, Gelaude D, Mosley JP, Travers J. A user-centered model for designing consumer mobile health (mHealth) applications (apps). J Biomed Inform. 2016; 60:243–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2016.02.002.

Kim Y, Briley DA, Ocepek MG. Differential innovation of smartphone and application use by sociodemographics and personality. Comput Hum Behav. 2015; 44:141–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.059.

Peñas-Lledó E, Bulik CM, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Baker JH. Risk for self-reported anorexia or bulimia nervosa based on drive for thinness and negative affect clusters/dimensions during adolescence: a three-year prospective study of the TChAD cohort. Int J Eat Disord. 2015; 48(6):692–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22431.

Dobmeyer AC, Stein DMA. Prospective analysis of eating disorder risk factors: drive for thinness, depressed mood, maladaptive cognitions, and ineffectiveness. Eat Behav. 2003; 4(2):135–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00013-8.

Krebs P, Duncan DT. Health app use among US mobile phone owners: a national survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015; 3(4):e101. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.4924.

Bhuyan SS, Lu N, Chandak A, et al. Use of mobile health applications for health-seeking behavior among US adults. J Med Syst. 2016; 40(6) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-016-0492-7.

Talmon J, Ammenwerth E, Brender J, de Keizer N, Nykänen P, Rigby M. STARE-HI—statement on reporting of evaluation studies in health informatics. Int J Med Inform. 2009; 78(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.09.002.

Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989; 13(3):319. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

Venkatesh V, Smith RH, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD, Walton SM. User acceptance of information and technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q 2003; 27(3):425–478.

Kwon M-W, Mun K, Lee JK, Mcleod DM, D’angelo J. Is mobile health all peer pressure? The influence of mass media exposure on the motivation to use mobile health apps. Convergence: Int J Res New Media. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516641065.

Higgins O, Sixsmith J, Barry MM. A literature review on health information- seeking behaviour on the web: a health consumer and health professional perspective. A literature review on health information-seeking behaviour on the web. Stockholm: ECDC; 2011.https://doi.org/10.2900/5788.

Viswanath K, Finnegan JR Jr, Gollust S. Communication and health behavior in a changing media environment. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bassy A Wiley Brand; 2015:327–48.

Baumgartner SE, Hartmann T. The role of health anxiety in online health information search. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011; 14(10):613–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0425.

Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009; 64(4):241–56.

Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, Van Gemert-Pijnen JE. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2012; 14(6):e152. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2104.

Ginters N. A review: how user characteristics affect the effectiveness of persuasive strategies in the health promotion domain of online interventions. (Master´s Thesis). The Netherlands: University of Twente, Positive Psychology and Technology; 2016.

Verkasalo H, López-Nicolás C, Molina-Castillo FJ, Bouwman H. Analysis of users and non-users of smartphone applications. Telematics Inform. 27:242–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2009.11.001.

The internet society. The global internet report. https://www.internetsociety.org/globalinternetreport/2016/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ISOC_GIR_2016-v1.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2017.

Eurostat data. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Internet_access_and_use_statistics_-_households_and_individuals. Accessed 1 April 2017.

PEW data. http://www.pewglobal.org/2016/02/22/smartphone-ownership-and-internet-usage-continues-to-climb-in-emerging-economies/. Accessed 1 April 2017.

Czech Republic Just Tops Russia for Mobile Penetration—eMarketer. https://www.emarketer.com/Article/Czech-Republic-Just-Tops-Russia-Mobile-Penetration/1012047. Accessed 14 Dec 2016.

Lupac P, Chrobakova A, Sladek J. Internet in the Czech Republic 2014. Prague; 2015. http://worldinternetproject.com/_files/_//234_report_wip_czr2014_eng_fin.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2014. OECD Statistics. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT#. Accessed 1 April 2017.

World Health Organization. Nutrition, physical activity, and obesity: Czech Republic; 2013. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/243293/Czech-Republic-WHO-Country-Profile.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 1 April 2017.

Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012; 7(4):284–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x.

Garner DM. Eating Disorder Inventory-3. Professional Manual. In: Lutz FL, ed. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. 2004.

Forbush KT, Wildes JE, Pollack LO, et al. Development and validation of the Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory (EPSI). Psychol Assess. 2013; 25(3):859–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032639.

Stephenson MT, Hoyle RH, Palmgreen P, Slater MD. Brief measures of sensation seeking for screening and large-scale surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003; 72(3):279–86. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14643945. Accessed 22 Dec 2016

Lang FR, John D, Lüdtke O, Schupp J, Wagner GG. Short assessment of the Big Five: robust across survey methods except telephone interviewing. Behav Res Methods. 2011; 43(2):548–67. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0066-z.

Cook B, Engel S, Crosby R, Hausenblas H, Wonderlich S, Mitchell J. Pathological motivations for exercise and eating disorder specific health-related quality of life. Int J Eat Disord. 2014; 47(3):268–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22198.

Cook B, Hausenblas H, Crosby RD, Cao L, Wonderlich SA. Exercise dependence as a mediator of the exercise and eating disorders relationship: a pilot study. Eat Behav. 2015; 16:9–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.10.012.

Claes L, Vandereycken W, Luyten P, Soenens B, Pieters G, Vertommen H. Personality prototypes in eating disorders based on the big five model. J Personal Disord. 2006; 20(4):401–16. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2006.20.4.401.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Czech Science Foundation (GA15-05696S) and the Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University.

Author statements

This manuscript presents original results that have not been previously published and the manuscript has not been submitted elsewhere.

Parts of the results have been reported in an abstract submitted for the Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine in San Diego, CA (April 2017).

The authors have full control of all primary data and they agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

The data are part of a study (THINLINE) funded by the Czech Science Foundation (Grantová agentura ČR, GA15-05696S) and the Faculty of Social Studies at Masaryk University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Masaryk University.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of Masaryk University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

Informed consent (implied by survey submission) was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Implications

Practice: Any potential intervention efforts utilizing mobile apps and targeting users of healthy lifestyle websites should consider underlying user characteristics such as gender, age, and weight status in selection of mHealth apps as well as consider the underlying psychological needs of users. App designers should incorporate user profiles in the design of mHealth apps to facilitate tailoring of app features to maximize their effectiveness as well as minimize any possible negative impact on users with different predispositions.

Policy: Standards for development of mHealth apps should include evaluation for potential to lead to psychological or behavioral vulnerabilities to avoid causing or exacerbating any maladaptive health behaviors in predisposed users.

Research: There are differences between app users and non-users of mHealth apps. Whereas some user characteristics such as excessive exercise or drive for thinness may help motivate app use, they should also be evaluated for potential to interact with mHealth app use in terms of leading to psychological harm or maladaptive health behaviors.

About this article

Cite this article

Elavsky, S., Smahel, D. & Machackova, H. Who are mobile app users from healthy lifestyle websites? Analysis of patterns of app use and user characteristics. Behav. Med. Pract. Policy Res. 7, 891–901 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-017-0525-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-017-0525-x