Abstract

Objectives

The aims of the present study are to provide population estimates for the prevalence of mindfulness use in the United States and to identify which groups are more likely to self-report mindfulness use.

Methods

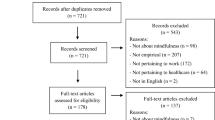

Using data from the 2017 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the current study analyzed 26,742 responses from adults in the United States and estimated patterns in the likelihood of self-reported mindfulness use across groups using logistic regression models.

Results

The results suggest that 5% of adults in the United States in 2017 had used mindfulness over the prior year, which is significantly more than the finding that 2% of adults in the United States had used mindfulness during the 12 months prior to the 2012 NHIS interview. The logistic regression models show that self-reported mindfulness use was less likely among married adults and more likely among women, sexual minorities, young and middle-aged adults, white adults, employed adults, adults without minor children in the family, adults from the West of the United States, adults with access barriers to healthcare, adults with cost barriers to healthcare, adults with mental illness, and adults with physical pain. Most notably, mindfulness use was reported by substantial numbers of respondents with access barriers to healthcare (10%), cost barriers to healthcare (9%), mental illness (15%), or physical pain (7%).

Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest an unequal distribution of mindfulness use across groups in the United States.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent decades, there has been a surge of scientific interest in mindfulness—the quality of awareness that emerges from purposefully and nonjudgmentally paying attention to the present moment with an attitude of openness, acceptance, and curiosity (Kabat-Zinn 2003). The research in the field has generally been limited by poor research methodologies and small sample sizes (Goleman & Davidson 2017), but the evidence to date suggests that mindfulness-based practices and programs can be effective for chronic pain (Hilton et al. 2017), anxiety (de Abreu Costa et al. 2019), and depression (Goldberg et al. 2019).

The proliferation of research on mindfulness-based interventions has coincided with efforts to integrate mindfulness-based practices and programs into a range of institutional settings, including the workplace, the military, the criminal justice system (Creswell 2017), and the government (Bristow 2019). There have not been many studies on the overall prevalence of mindfulness use in society, but Burke et al. (2017) analyzed the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and found that an estimated 2% of adults in the United States had used mindfulness during the 12 months prior to the survey interview. The evidence to date suggests that mindfulness use in the United States varies widely depending on age, region, race, gender, sexual orientation, cost barriers to healthcare, access barriers to healthcare, mental illness, and physical pain (Burke et al. 2017; Macinko & Upchurch, 2019; Morone et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019).

While several theoretical models have been developed to explain the variance across groups in healthcare utilization (Mechanic 1962; Parsons 1951; Suchman 1965), the Andersen (1995) healthcare utilization model has also been used to predict mindfulness use in the United States (Macinko & Upchurch, 2019). The model involves three main predictors of healthcare utilization: (1) predisposing factors—characteristics that predispose individuals to use health services, which can include age, race, and gender; (2) enabling factors—characteristics that enable individuals to access health services, which can include a general inability to afford health services; and (3) health needs—characteristics that create a need for individuals to utilize health services, which can include mental illness and physical pain. Using the Andersen (1995) healthcare utilization model and publicly available data from the 2017 NHIS dataset, the aims of the present study are to provide population estimates for the prevalence of mindfulness use in the United States and to identify which groups are more likely to self-report mindfulness use.

Methods

Participants

The present study provides a secondary analysis of data from the 2017 NHIS dataset. The NHIS is a nationally representative survey of the US population with information on sociodemographic characteristics and health status. The publicly available data files were weighted to reflect the civilian noninstitutionalized population and contained responses from 26,742 adults aged 18 years or above, which was 80.7% of the total sample of eligible adults (33,143).

Measures

The dependent variable for the present study was self-reported mindfulness use during the 12 months prior to the survey interview. The current study used twelve independent variables that were relevant to the Andersen (1995) healthcare utilization model: age, region, race, gender, sexual orientation, marital status, family composition, and employment status were analyzed as predisposing factors; access barriers to healthcare and cost barriers to healthcare were analyzed as enabling factors; and mental illness and physical pain were analyzed as health needs. The exact wording and recoding of all the questions and answers can be found in Appendix 1 in the Supplementary Materials.

“Refused,” “Not Ascertained,” and “Do not Know” (3.2% of the responses for the dependent variable; see Table A1 in Supplementary Materials Appendix 2) were coded as “Use Not Reported” for the dependent variable, which ensures that the weighted sample reflects national estimates. While respondents using techniques similar to mindfulness-based practices are unlikely to self-report mindfulness use, it is assumed that mindfulness users generally know that they are using mindfulness-based practices and would therefore be able to report it. It is also important to note that the overall findings are broadly the same when “Refused,” “Not Ascertained,” and “Do not Know” are coded as missing values for the dependent variable (see Tables A2–3 in Appendix 3 in the Supplementary Materials). The response in the 2017 NHIS dataset can appear as “Not Ascertained” in several situations, including when the field was left blank or the respondent discontinued the interviews at some point after completing the first three sections (NHIS 2017).

Data Analyses

The present study used descriptive statistics to present an overview of self-reported mindfulness use (Tables 1 and 2). The likelihood of self-reported mindfulness use across groups was calculated with three multiple logistic regressions to calculate adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (Table 3). The adjusted odds ratios with a greater value than 1 suggest that individuals in the group were more likely to have self-reported mindfulness use during the 12 months prior to the survey interview. Conversely, the adjusted odds ratios with a value less than 1 suggest that the individuals in that group were less likely to have self-reported mindfulness use during the 12 months prior to the survey interview. The data analyses make use of sampling weights to produce representative estimates.

Results

Table 1 displays the percentage of self-reported mindfulness use. The results show that 5% of the respondents reported mindfulness use during the 12 months prior to the survey interview, which suggests that thirteen million adults in the United States had used mindfulness in the analyzed time period, based on the population estimates from NHIS.

Table 2 displays the percentage of self-reported mindfulness use across groups. Most notably, mindfulness use was self-reported by substantial numbers of respondents with access barriers to healthcare (10%), cost barriers to healthcare (9%), mental illness (15%), or physical pain (7%).

Table 3 displays estimates from three logistic regression models based on variables that might reasonably be expected to be casually prior to mindfulness use during the 12 months prior to the survey interview: predisposing factors (model 1); predisposing factors and enabling factors (model 2); and predisposing factors, enabling factors, and health needs (model 3). Taken together, self-reported mindfulness use was less likely among married adults and more likely among women, sexual minorities, young and middle-aged adults, white adults, employed adults, adults without minor children in the family, adults from the West of the United States, adults with access barriers to healthcare, adults with cost barriers to healthcare, adults with mental illness, and adults with physical pain.

Discussion

The present study analyzed the 2017 NHIS dataset to provide population estimates for the prevalence of mindfulness use in the United States and to identify which groups are more likely to self-report mindfulness use. The findings show that 5% of respondents reported mindfulness use during the 12 months prior to the survey interview, which suggests that thirteen million adults in the United States had used mindfulness in the analyzed time period. Taken together, self-reported mindfulness use was less likely among married adults and more likely among women, sexual minorities, young and middle-aged adults, white adults, employed adults, adults without minor children in the family, adults from the West of the United States, adults with access barriers to healthcare, adults with cost barriers to healthcare, adults with mental illness, and adults with physical pain. Most notably, mindfulness use was self-reported by substantial numbers of respondents with access barriers to healthcare (10%), cost barriers to healthcare (9%), mental illness (15%), or physical pain (7%).

The findings in the current study suggest a significantly higher prevalence of mindfulness use among adults in the United States in 2017 than in 2012, which mirrors the overall increase in meditation use between 2012 and 2017 (Clarke et al. 2018). The results broadly confirm earlier analyses of the sociodemographic characteristics and health status of mindfulness users (Burke et al. 2017; Macinko & Upchurch 2019; Morone et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019), but the present study also finds self-reported mindfulness use to be significantly associated with marital status, family composition, and employment status.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present study has several limitations worthy of consideration. First, the sample has been weighted to be representative of the adult population in the United States, which increases the reliability and accuracy of the population estimates. The analysis was, however, conducted with data collected in 2017 and might not reflect current trends and characteristics of mindfulness users. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study prevents causal inference about the mental and physical health status of the respondents. The causal effects of the mindfulness use cannot be established, even if the research thus far broadly suggests a positive effect on mental and physical health from mindfulness-based interventions. Future research should explore barriers to mindfulness use and ways to promote a more equally distributed use of mindfulness-based practices and programs.

References

Andersen, R. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 1–10.

Bristow, J. (2019). Mindfulness in politics and public policy. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 87–91.

Burke, A., Lam, C. N., Stuffman, B., & Yang, H. (2017). Prevalence and patterns of use of mantra, mindfulness and spiritual meditation among adults in the United States. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17(1), 316.

Clarke, T. C., Barnes, P. M., Black, L. I., Stussman, B. J., & Nahin, R. L. (2018). Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among US adults aged 18 and over. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db325-h.pdf

Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 491–516.

de Abreu Costa, M., de Oliveira, G. S. D. A., Tatton-Ramos, T., Manfro, G. G., & Salum, G. A. (2019). Anxiety and stress-related disorders and mindfulness-based interventions: A systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis and meta-regression of multiple outcomes. Mindfulness, 10(6), 996–1005.

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2019). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the treatment of current depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(6), 445–462.

Goleman, D., & Davidson, R. (2017). The science of meditation: How to change your brain, mind and body. Penguin UK.

Hilton, L., Hempel, S., Ewing, B. A., Apaydin, E., Xenakis, L., Newberry, S., Colaiaco, B., Ruelaz Maher, A., Shanman, R. M., Sorbero, M. E., & Maglione, M. A. (2017). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 199–213.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

Mechanic, D. (1962). The concept of illness behaviour. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 15(2), 189–194.

Morone, N. E., Moore, C. G., & Greco, C. M. (2017). Characteristics of adults who used mindfulness meditation: United States, 2012. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 23(7), 545–550.

NHIS (2017). Survey description. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2017/srvydesc.pdf

Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. The Free Press.

Suchman, E. (1965). Stages of illness and medical care. Journal of Health and Human Behavior, 6(3), 114–128.

Wang, C., Li, K., & Gaylord, S. (2019). Prevalence, patterns, and predictors of meditation use among US children: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 43, 271–276.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. OS analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SF and MM supervised and commented on the manuscript drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The current study was exempt from review by the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Sociology (DREC) at the University of Oxford.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 41.9 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simonsson, O., Martin, M. & Fisher, S. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Health Status of Mindfulness Users in the United States. Mindfulness 11, 2725–2729 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01486-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01486-4