Abstract

In many subsurface engineering geoscience applications the impact of thermal, hydraulic, mechanical and chemical (THMC) processes needs to be evaluated. Coupled process models require solution of the partial differential equations describing energy or mass balance. Ignoring the coupling of these processes can lead to a significant oversimplification which may not adequately represent the systems being modelled. Incorporation of coupled processes and associated phenomena inevitably leads to numerical stability issues due to very different scales in terms of spatial distribution, time and parametrical heterogeneity. One approach to simplify the computational demands is to integrate analytical and physical models into standard numerical modelling techniques (in this case finite elements), effectively adding sub-grid scale and sub-time scale information to the model. We present such an approach for the simulation of fluid flow through a fracture validated against experimental data and cross comparison with results of other modelling teams within the DECOVALEX 2015 (development of coupled models and their validation against experiments) project (http://www.decovalex.org). By replacing the mechanical behaviour and chemical transport processes with physical models, and by utilising the static nature of the temperature changes, only the hydraulic system required numerical solution in a highly coupled problem. Physical models for fracture closure due to pressure solution, fracture opening due to chemical dissolution, the development of channel flow and a change in the reactive transport characteristics with time were implemented and are described here. The main features of the experimental data could be replicated, although lying outside of the parameter range suggested by the literature. Comparison with other teams using different modelling approaches indicated internal consistency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fluid flow in the subsurface is receiving increasing attention as a major driver for many of the geological surface phenomena. Fractures form the main conduits for fluid flow in the subsurface through the crystalline rock and exhibit a significant control on the fluid flow through porous rock depending on the ratio of the permeability of the fracture to the matrix. Understanding the changes in fluid flow behaviour through fractured rock under variable chemical (C), hydraulic (H), thermal (T) and mechanical (M) conditions is, therefore, of interest to fundamental geological research questions, e.g. Tsang (1991). It is also of importance to applied geo-engineering problems such as hydrocarbon recovery, geothermal energy recovery, groundwater resources and the formation of geo-repositories for CO2 storage, water disposal and nuclear waste disposal.

The evolution of the fluid transport characteristics of fractures, expected to be controlled by the fracture aperture, permeability, in situ stress and geochemistry, has important impacts on the overall transport characteristics of the fractured rock mass. To accurately predict that behaviour where the field variables of stress, pressure, temperature and geochemistry are changing significantly, fully coupled THMC modelling tools need to be applied. However, fully coupled modelling of even single fractures has been limited. This is principally due to the fact that the THMC processes take place at very different spatial scales and rates, leading to significant numerical complexities in attempting to couple the solution of the energy or mass balance equation. A full numerical solution of the equation system is often time consuming and requires intricate numerical control to ensure solution stability, (e.g. Ouyang and Tamma 1996; Kolditz 1997; Wang et al. 2011a, b).

Choices have to be made in terms of the order of importance of the processes (THMC) which are simulated, and the phenomena (interaction of the processes) which are represented in the simulation. In some cases, significant data density is available; however, usually sparse data are available to validate models. Often there will be a significant data density for one aspect of the simulation but little data for another equally important area of the simulation. Parallel processing has offered a significant speed-up in terms of simulation and the capability of handling large data sets; however, basic interpretation of the conceptual models and understanding the physical phenomena occurring will always remain paramount.

Hybrid numerical methods combine the advantage of numerical solutions, such as finite difference, finite element or finite volume, with physically based analytical models. Examples of such approaches include the hybrid Trefftz finite-element method (e.g. Qin 2005; McDermott et al. 2011), the extended finite element method (XFEM) where basis functions are replaced with discontinuous functions to represent singularities (e.g. Moës et al. 1999; Mohammadi 2008) and more general solutions via source terms, e.g. Pruess (2005) and McDermott et al. (2007). Numerical models provide a flux-based solution of the mass and energy balance equations for the processes accounting for spatially variable heterogeneous parameter distributions located geometrically by grids. Analytical and physical models of phenomena take into account pure mathematical and physical descriptions of phenomena occurring (analytical models), or empirical observation (physical models). Coupling numerical models with analytical and physical models is a means of including extra information at a sub-grid scale into the overall modelling approach. In many cases, the solution of one or more of the main processes can be replaced by an analytical or physical model, thereby significantly reducing the computational demands and increasing flexibility.

This approach of combining the advantages of the standard numerical simulation approaches, with other physical or analytical models of the phenomena operating and thereby adding information to the model, has been applied successfully in a number of fields. These include geothermal work, membrane simulation, CO2 sequestration, geomechanics and broader engineering fields, e.g. (Moës et al. 1999; Celia and Nordbotten 2009; McDermott et al. 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011; Watanabe et al. 2012).

The objective of this paper is to present new methods used to model fluid flow through a single fracture where the aperture is changing with time as a result of non-elastic mechanical and chemical processes under changing fluid flow rates and temperatures. The work presented is embedded in the current DECOVALEX project (development of coupled models and their validation against experiments, http://www.decovalex.org). This was established and is maintained by a range of waste management organisations, regulators and research organisations to help improve capabilities in experimental interpretation, numerical modelling and blind prediction of complex coupled systems.

Within the fracture considered, the fluid flow is occurring at such a rate as to make numerical simulation by monolithic or staggered coupling to the other main processes unusable. The spatial geometry of the fracture surface is discretised at a sub-millimetre scale, defining the aperture of the fracture and thereby the heterogeneous permeability of the fracture. Fluid velocities through the fracture are at a rate of mm/s; the fracture aperture is of the order of ~20 μm. Experimental data and model comparison of other DECOVALEX teams (Bond et al. 2014) are used to validate the modelling approaches. Where experimental data are not available, cross model comparison provides a method of increasing certainty in the model predictions.

Experimental investigation of such systems is complex, requiring several variables such as temperature, fluid flow, pressure and chemical concentrations to be controlled and monitored over extended periods of time. There are not many examples of such work being undertaken. Yasuhara et al. (2006) present such experimental data for fractured novaculite. The time scale of the experimental work is of the order of 3200 h (~130 days) whereas the rate of advective flow is of the order of 1 mm/s, such that total fluid residence time in the fracture is of the order of 1 min.

Yasuhara and Elsworth (2006) present numerical modelling results in later papers of this experimental work which includes the application of a particle tracking approach coupled with source terms in the solute transport solution to represent dissolution of the fracture surfaces and subsequent aperture closure during reactive transport. In this current paper, only the hydraulic process is solved numerically; analytical and physical models are used to simulate the chemical and mechanical processes. This, thereby, significantly reduces the computational demands, and avoids numerical stability issues of transport-linked solutions (Courant et al. 1928; Charney et al. 1950; and several subsequent authors).

Three key phenomena due to the coupling of the processes are represented in the model, using analytical or physical models coupled with the hydraulic simulation.

-

1.

Mechanical closure of the fracture due to removal of material (pressure solution, stress corrosion)

-

2.

Kinetic controlled dissolution of the fracture surface leading to an opening of the fracture due to removal of material (chemical solution)

-

3.

Development of channel flow.

Experimental data

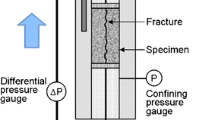

Yasuhara et al. (2006) investigated experimentally the THMC evolution of an artificially fractured sample of Arkansas Novaculite (50 mm diameter × 89.5 mm length; micro- or crypto-crystalline quartz with only minor amorphous quartz). This sample contained one artificial fracture which was subject to the following conditions and measurements:

-

1.

Pre-experiment fracture surface profiling using laser profilometer to establish the surface topography.

-

2.

Hydraulic isolation and variable prescribed flow rates of de-ionised water through the fracture.

-

3.

Mechanical confinement of the fracture through the application of an external confining pressure of 1.72 MPa, which resulted in a net effective stress of 1.38 MPa across the fracture, whereby the maximum differential fluid pressure across the sample was 0.1 MPa, and the back pressure 0.34 MPa.

-

4.

Heating of the whole sample to different temperatures with time.

-

5.

Measurement of the chemical composition of the outflow and inflow; dissolved Si (ppm) and pH.

-

6.

Measurement of differential pressures across the sample.

-

7.

Post-experiment measurement of the fracture apertures using Wood’s metal injection.

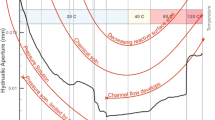

The evolution of the pressure difference for a given flow rate gives an indication of the effective hydraulic aperture across the specimen. The general experimental design is shown in Fig. 1. An illustration of the fracture surface topography is shown in Fig. 2. The experimental regime over the 3150 h experiment is shown in Fig. 3.

Experimental details, modified from Yasuhara et al. (2006). Arrow shows the positive flow direction

Topography of one side of the novaculite fracture prior to the experiment, positive flow direction is shown using the arrows. Units are mm, with no vertical exaggeration. Data from Yasuhara et al. (2006) supplied by pers comm

The sample is subject to changing flow rates during the first half of the experiment including a period of flow reversal (isothermal period), followed by a step-wise increase in temperature peaking at 120 °C (non-isothermal period). One key period of the experiment was between 858 and 930 h where complete fluid pressurisation of the sample was lost. This is referred to as the ‘shutdown period’.

The experimental data show a progressive increase in normalised differential pressure (and hence a corresponding decrease in implied aperture—Fig. 4) which is largely insensitive to the flow rate, with a much more complex evolution once the flow reverses and temperature effects come into play. The Si concentration (Fig. 5) shows a much simpler evolution with a relatively constant outflow concentration observed during the isothermal period, with major changes in concentration only being observed as the temperature changes. The pH results are not considered here as the significant unstructured variation in both input and output pH was considered unreliable due to CO2 contamination.

Measured normalised differential pressure and implied hydraulic aperture with shutdown period highlighted (modified from Yasuhara et al. 2006)

Measured outflow Si concentration (ppm) with the flow reversal highlighted (modified from Yasuhara et al. 2006)

The hydraulic aperture, e h, is derived from the experimental results and combining Darcy’s law and the cubic law (Witherspoon et al. 1980). Flow rate Q in m3 s−1 measured experimentally is related to the cross-sectional flow area, A in m2, k is the intrinsic permeability in m2, μ is the dynamic viscosity in Pa s and p is the fluid pressure in Pa.

For a fracture, the intrinsic permeability is related to the hydraulic aperture of the fracture, \(e_{\text{h}}\), in m

The cross-sectional flow area is given by \(e_{\text{h}} L\) where L is the length of the fracture normal to flow in the sample (usually sample width). The hydraulic aperture is, therefore,

The normalised differential pressure, \(\Delta p_{\text{n}}\), is calculated by relating the differential pressure \(\Delta p_{\text{r}}\) dynamic viscosity, \(\mu\), and flow rate, \(Q\), under ongoing experimental conditions to the initial conditions of the experiment with respect to viscosity and flow, \(\mu_{\text{i}} ,Q_{\text{i}}\), before any changes to flow rates or temperature had been applied.

Simulation

Conceptual model

Before a numerical model can be created, a clear conceptual understanding of the main processes and phenomena present has to be formulated. The key phenomena considered to be dominating the response of the experimental system are illustrated in Fig. 6. These include pressure solution due to contact stress leading to hydraulic aperture closure, pressure solution limited by a critical stress, chemical solution leading to an aperture increase, a decrease in reactive surface area as the experiment proceeds and the development of channel flow.

Fluid flow in the fracture is considered to be the main driving force behind the mechanical and chemical response of the system. Therefore, the heterogeneities in the fluid flow system have a significant control on the system behaviour. Mechanical closure of the fracture aperture controls the changes in the heterogeneities in the fluid flow system and the fluid pressure alterations in the system. The mechanical closure is driven by pressure and chemical solution, operating on a significantly longer time scale than the fluid flow, and also at a much smaller spatial scale than the fluid flow.

Pressure solution is a function of the contact stress, which in turn is related to the confining stress and the fluid pressure in the fracture (Elias and Hajash 1992; Yasuhara and Elsworth 2008; Bernabé et al. 2009; Choi et al. 2013; Miyakawa and Kawabe 2014). Temperature varies throughout the experiment, but remains static for long periods of time and there are no temperature gradients. Temperature impacts the material parameters of the system statically, so is set as a domain state variable. When changes in temperature in the experiment occur, these are represented by changes to the material properties in the other system variables, e.g. the viscosity of the fluid.

The hydraulic system was solved numerically, and analytical and physical models were used to include information about the mechanical deformation, pressure solution and chemical solution as a function of the external static variables and the fluid properties in the system. This is illustrated schematically in Fig. 7, given in more detail in Fig. 8 and described in detail in the following text.

The fracture was represented by a mesh generated from the profile data provided by Yasuhara et al. (2006) and pers. comm. The original profile data were provided at a horizontal resolution of 50 μm, and a vertical accuracy of 10 μm, providing circa 3 million data points (for a sample 5 cm × 9 cm). The behaviour of the fracture was evaluated for a number of mesh resolutions, and a resolution of 800 μm was found to represent the main behaviour characteristics, and reduced the data density to circa 6300 points. To transfer the data to mesh elements for numerical solution, aperture data were picked at this spatial density and used directly to calculate the permeability of the mesh element. There was no spatial averaging of the data. Point data were selected with the aim of maintaining a representation of the original statistical distribution of the aperture distribution.

The intrinsic permeability of each element, \(k^{e}\), representing the fracture surface assuming laminar flow is given by

where \(e\) is the aperture, and α and β represent the 2D coordinate system in the plane of the fracture. Although using this expression overestimates the hydraulic conductivity of rough fractures, it provides a good approximation of the corresponding permeability distribution given a particular aperture distribution. The fracture plane is discretised into individual elements, and an aperture is mapped to each element, Fig. 9, (e.g. Koyama et al. 2006; Kalbacher et al. 2007).

A disadvantage of this standard type of approach is that sub-grid scale information is lost in the numerical simulation due to the limitations of the geometrical approximation of the fracture surface. Any resolution of a discrete surface needs to approximate the actual analogue fracture surface and contact geometry. In the simulations, here the fracture surface resolution was selected at 800 μm. One approach to addressing this loss of information at a sub-grid scale is to introduce a further physical conceptual model into the numerical analysis.

Several authors have shown that the surface of fractures can be considered to have fractal geometry, e.g. Odling (1994), Glover et al. (1999) and even multi-fractal, Stach et al. (2001) down to the actual grain size of contact. Beyond that, electrostatic layers of contact are also invoked in the literature for understanding the effects of chemical dissolution of surfaces, since originally Helmholtz (1853) and several authors since, e.g. Sverjensky (1993) and references therein. A key characteristic of fractal geometry is that the statistical characteristics of the surface are independent of the length scale. Therefore, the control at the scale of interaction should be the same as the control at the element scale. Applying this concept means it is possible to assume that the statistics which govern the probability distribution of the amount of contact area of a fracture can also be taken to indicate the “micro” contact area of the fractures discretised to the length scale of the elements. This means that conceptually the area of the fracture surface represented by an element also displays a minute surface variation and roughness compatible with the characteristics of the entire fracture area, (Fig. 10).

The model described in this paper has been integrated into the scientific code OpenGeoSys (OGS), a standard Galerkin finite element solver (Kolditz et al. 2012). The hydraulic conditions applied during the experiment were matched in terms of boundary conditions and fluid flow. The external confining pressure was kept constant and the internal pressure varied. The temperature throughout the whole model was altered as a function of time as given by the experimental conditions.

In the fracture, fluid flow is represented by Eq. (6) for a unit volume

where S is the storativity coefficient (pa−1), k denotes the intrinsic permeability [\({\text{m}}^{2}\)], p is the fluid pressure in Pa, and Q is a source/sink (s−1). This equation is valid for a saturated, non-deforming porous medium with heterogeneous permeability. The fracture is represented by the heterogeneous permeability distribution mapped onto a 2D mesh. To evaluate the fluid pressure distribution within the fracture with a heterogeneous permeability distribution, a numerical solution is required. The solution of Eq. (6) using the finite element technique is covered in standard works such as Istok (1989), Lewis and Schrefler (1998) and Zienkiewicz and Taylor (2005).

The experimental observations show that during fluid flow through the fracture the aperture generally reduces with time for the first 1500 h, after which it starts to increase. This means that the solution of the pressure distribution within the fracture is time dependent; therefore, a series of time steps are defined to evaluate the fracture aperture. The time dependency is captured by updating the aperture distribution at the end of every time step. Storage of the fracture system (6) is neglected allowing repeated steady state solutions to be applied. The fluid pressure and fluid velocity fields are recovered for each element at the start of a time step from the previous solution, and used as an explicit input to the analytical solutions.

Mechanical closure

Mechanical closure approach

The mechanical closure is calculated implicitly for the current time step using a series of explicit iterations. The iteration control variable is the increase in the number of contacts across a surface as the aperture closes. Contact is defined from the profile data when a fracture aperture mapped to an element is less than a defined minimum separation, in this case 0.11 nm. If the aperture is larger than this, then the element is considered to be a channel (Fig. 11).

Contact stress, \(\sigma_{\text{a}}\), is defined as the normal confining stress across the fracture minus the fluid pressure in the fracture, \(p\), carried by the fractional contact area of the fracture (CA).

When the contact stress is evaluated at the scale of an individual element, then the fluid pressure in the element is taken. The contact stress at the start of a time step is taken to evaluate the stress-dependent closure of the fracture explicitly for the first iteration. The increase in the number of contacts for this stress closure calculated. The method of bisecting intervals is used to approach the final implicit solution for closure during this time step, illustrated in Fig. 12.

Closure mechanism

For the implementation, the numerical solution needs to be able to cope with a changing aperture time step by time step. Competition between different closure mechanisms is considered in more detail elsewhere in the literature, e.g. Yasuhara and Elsworth (2008) and Zhang et al. (2012). Here, surface pressure solution was considered the dominant mechanism by which both aperture closure and elevated concentrations of Si in the effluent could be obtained during closure of the fracture. The general form describing pressure solution is given as:

where \(m_{{{\text{ps}},i}}\) is the change in mass of species i (quartz in this case) due to pressure solution, \(k^{ + }\) is the pressure dissolution rate constant (mol/m2/s), \(C_{i}\) is the concentration of silicon in the fluid (ppm), \(C_{\text{eq}}^{\sigma }\) is the stress-enhanced solubility of i (ppm), \(\alpha\) is an empirical roughness factor (–), \(A_{{{\text{ps}},i}}\) is the local effective area of species i (m2) for pressure solution, \(\sigma_{\text{a}}\) is the effective stress over the area of contact (Pa), \(\sigma_{\text{c}}\) is the critical stress (Pa), \(\beta_{\text{c}}^{{}}\) is the ‘burial constant’ (–), \(\Delta b_{i}\) is the incremental change in aperture due to the change in mass of species i, \(V_{{{\text{m}},i}}\) is the molar volume of species i (m3/mol), R is the gas constant (J/mol/K) and T is the temperature (K). Pressure solution was implemented such that

f is some fitting factor used to match results, and which has a physical meaning related to the roughness of the surface area. The exponential function was replaced with a linear approximation, and burial effects not taken into account, similar to Yasuhara and Elsworth (2006) and Gratier et al. (2009) with works cited therein. Pressure solution kinetic effects were taken into account as a concentration limit during closure.

A critical pressure solution limit is discussed by Revil (1999) and Yasuhara et al. (2004). Where less stress than this occurs, no further pressure solution can occur. This is given by

where \(E_{\text{m}}\) and \(T_{\text{m}}\) are the heat and temperature of fusion, respectively (E m = 8.57 kJ mol−1; T m = 1883 K for quartz), T is the current temperature in kelvin and \(V_{\rm m}\) is the molar volume \(2.27\, \times \,10^{ - 5} \,{\text{m}}^{3} / {\text{mol}}\). Using the values for quartz given, the limiting pressure can be calculated to be approximately 80 MPa.

During the mechanical simulation, the contact stress at an element level was calculated, and compared to this critical stress value. A simple evaluation under the experimental conditions demonstrates that, at the scale of the discretisation, the contact stress would be of the order of 30 MPa for a contact area of 5 %. However, from the experimental results, it was clear that aperture closure was continuing at up to circa 20 % of the fracture area being in contact, also indicated by the evaluation of the woods metal print.

From the literature, a number of authors suggest that stress corrosion would produce the effect of continued closure; however, stress corrosion would not lead to the observed silicate concentrations in the effluent. It is possible that concurrent chemical dissolution actually controls the Si concentration in the effluent during this initial phase. However, the maximum amount of chemical dissolution is limited by matching the experimental data after ~1500 h (Fig. 6), where the hydraulic aperture is only seen to increase, and there is no clear relationship between the fluid flow rates and the concentration of Si in the effluent. Applying the amount of chemical dissolution seen after 1500 h to the initial phase of closure allowing only stress corrosion and excluding pressure solution does not produce the experimentally measured Si concentration. With the data available, it is impossible to completely rule one or the other process out, or to quantify their relative significance. It is likely that both are operating to some degree.

Inclusion of a sub-grid scale physical model

Applying the fractal surface model as discussed above (Fig. 10) allows the critical stress value to be approximated as:

This approach allows a reasonable fitting of the data assuming a critical stress value of circa 30 MPa. Although below the theoretical value of 80 MPa, the use of a sub-grid scale physical model has significantly closed the gap between the numerical modelling approximation and the experimental results. Further changes to Eq. (14) could include factors to account for the discrete geometry of grain to grain contacts, but is really a further extension to the inclusion of sub-grid scale information. However, data to validate this are not available in the experimental work undertaken and so this is not included in the modelling.

Closure distribution

The amount of material lost through pressure solution per element is calculated, and summed using Eq. (11) and (12). This provides a solution for the total amount of aperture closure \(\Delta e_{t}\) which is then weighted across the whole fracture plane. The iteration is controlled time wise such that the change in fracture aperture is not allowed to exceed 5 % of the fracture aperture at any time, ensuring numerical stability. Having calculated the total amount of closure across the model, the closure needs to be distributed to the channels. The distribution is weighted according to the fluid pressure in the channel, such that areas with lower fluid pressure see higher aperture change than those with high fluid pressure. This approach reflects the relationship between the effective stress and the amount of closure occurring. The element weighting factors, \(w_{\text{el}}\), are given by Eq. (15)

where \(p_{\text{e}}\) is the fluid pressure in the element, min \(p_{\text{e}}\) and max \(p_{\text{e}}\) the smallest and largest fluid pressure seen in the whole of the fracture plane. The aperture change for the channel elements is given as:

where \(nc\) represents the number of contacts across the fracture plane.

Chemical dissolution

Chemical dissolution concept

Aqueous dissolution/precipitation was modelled using conventional transition state theory (Eyring 1935):

where \(\frac{{{\text{d}}m_{{{\text{d}},i}} }}{{{\text{d}}t}}\) is the change in molar mass of species i (quartz in this case) due to dissolution/precipitation, k is the dissolution rate constant (mol m−2/s1), \(t\) is time (s), \(A_{{{\text{e}},i}} \left( S \right)\) is the mineral reactive surface area (m2), \(Q\) is the ion activity product for the solid of interest (dimensionless) and \(K\) is the equilibrium constant for mineral dissolution (dimensionless). Given the rate of fluid flow through the fracture, a first approximation of the chemical behaviour enabled the kinetic behaviour to be neglected. However, due to the heterogeneity within the fracture surface and the later higher temperatures of the experiment, the kinetic behaviour was considered necessary for a more accurate solution.

Numerical simulation of advective dominated transport is controlled by the Courant number, (Courant et al. 1928), which expresses the stable time control of the simulation as a function of the advective velocity and the discrete size of the grid used for the coordinate system of the numerical simulation. Should a conventional mass balance approach be used to approximate the advective dispersive transport, a stable time stepping scheme would require time discretisation on the order of a few seconds. However, given that the experimental conditions remain constant over several days, evaluation of these periods of time in terms of seconds would prove computationally expensive. Here, we develop a new approach to simulate the advective transport coupled with the advective flow. This approach allows both the development of the concentration profile within the fracture plane and the overall influence of the concentration profile on the fracture dissolution rate with time to be evaluated without requiring micro-time stepping.

For the numerical solution of the hydraulic system, a time step is chosen independent of the rate of the dissolution process. For instance considering dissolution at 120 °C, a time step of 10 h may be taken to evaluate the concentration profile. The amount of fluid passing through an element within the fracture during this period of time is evaluated. The residence and contact time of the fluid within the element are calculated and used to evaluate the amount of mass dissolved into this package of fluid in the given time.

Non-linear sub-time stepping

Kinetic dissolution is non-linear, such that an explicit linear-based approximation of the evolution of the concentration would lead to large errors. However, when considered in a log–log evaluation, the dissolution can be seen to become approximately linear (Fig. 13). To better represent the kinetic dissolution, a sub-time step iteration carried out on a log-based evaluation of the time step was applied. The time step comprised several sub-time steps. Using logs, this can be expressed as:

Expressed generically for n + 1 timesteps

The individual sub-time steps \(\Delta t_{s}\) are given by

where k is an integer from 0 to n.

The sum of a geometrical series for n terms is given as:

This can be expressed as:

This non-linear equation can be solved for r using the Newton–Raphson method for given values of a and Δt. This approach is used to evaluate n equally spaced log sub-time steps within a given time step.

Streamline controlled dissolution

As the rate of dissolution of a mineral is kinetically controlled (i.e. the rate of dissolution of a mineral into a fluid is controlled by the concentration of the mineral in the fluid), it is therefore necessary to evaluate the concentration of the mineral in the fluid throughout the fracture and track the development of the concentration throughout the discretised fracture surface. The standard approach to this would be a discretised solution of the mass transport equations, which would require the numerical stability criteria (Courant and Nuemann) to be adhered to. Simulating the fracture discussed here in accordance with the Courant criteria would have required a time step of the order of 10 s. To cover 10 h would have required 3600 time steps including a full solution of the advective dispersive transport equations with all the associated stability issues. Here, we develop a method whereby streamline information is used to enable a rapid approximation of the development of the concentration profile and evaluation of the amount of dissolution. Streamline model approaches have been used by a number of authors previously, including Finkel et al. (1998, 1999), McDermott et al. (2005), Vilarrasa et al. (2011).

Mass transport is usually seen as comprising an advection term and a diffusion/dispersion related term. When advection is dominant, then the diffusive term can be neglected parallel to the direction of flow. Distribution of the solute within the advecting fluid under advection dominant conditions is then principally controlled by the local streamlines (flow paths) and their mixing. In a steady state hydraulic solution, the length of time any given surface is in contact with the fluid, and the amount of fluid it is in contact with, can be calculated. The impact of the dissolution and associated chemical concentration in the fracture fluid on the kinetically controlled dissolution of the fracture surface can then be explicitly approximated, assuming that the surface area of the fracture changes relatively slowly due to chemical dissolution.

The advective transport within the fracture is controlled by the boundary conditions and the distribution of the aperture sizes within the fracture. The hydraulic solution provides the advective velocity vectors in each element. Sequentially, element by element, the advective velocity vectors can then be used to determine the contribution of each immediately downstream element on the element under consideration. We term the element under consideration the “active” element for ease of nomenclature later. This then enables Q, the ion activity product for the mineral of interest Eq. (17), to be evaluated for the element. Naturally, this solution only takes into account the elements immediately downstream of the active element. However, by sequentially iterating throughout the whole fracture surface, and immediately updating the concentration profile until a steady state solution is obtained, all the downstream contributions for each active element are taken into account. The concept is illustrated in Fig. 14, and the element geometry is given in Fig. 15.

The overall concentration of the flux (Q de) into the active element from the downstream elements (i = 1, 2, 3 ..no edges) is given as a weighted average of the velocity of flow into the element from the downstream elements, the cross-sectional area to flow of these elements (apertures × side length) \(\left( {A_{{{\text{fi}}}} } \right)\) and the concentration of the flux in the downstream elements (Q i ).

This is mixed with the volume of fluid in the active element at the start of the time step to give the initial ion activity product for the active element as

where \(v_{e} A_{\text{f}}\) is the flux through the active element.

Sub-time stepping as described above is now used to evaluate the kinetically controlled change in concentration in the fluid which comes into contact with the fracture surface represented by the active element. The total volume of fluid which has come into contact with the fracture surface represented by the active element in a time, Δt, comprising several sub-time steps \(\Delta t_{\text{s}}\) is

During each sub-time step, \(\Delta t_{\text{s}}\), first excluding the kinetic terms for clarity, the amount of fracture surface dissolved into the fluid is given by

where \(\alpha_{\text{c}}\) is a parameter to take into account extra surface area available to chemical dissolution as a result of the freshness of the fracture surface, discussed in more detail below.

The incremental change in the concentration of the dissolved substance in the fluid is

the factor 1000 converting a molar concentration into molal. Introducing the kinetic control

where \(\left( {t_{\text{s}} = 0} \right)\) that is to say, the initial conditions for the start of the sub-time step iteration, then \(Q_{{e(t_{\text{s}} - 1)}} = Q_{e(t - 1)}\).

Then, the concentration at the end of the sub-time step is then given by

The sub-time stepping is continued until Eq. (19) is satisfied, that is the sum of the sub-time steps equals the solution time step. At this point, the active element flux concentration is updated and the next element is evaluated. This methodology provides an explicit value for the flux concentration of the active element, and is repeated for every element within the fracture surface (Fig. 16). However, the final solution of the flux concentration requires an implicit solution including several iterations over all the elements within the fracture surface. This allows changes in the flow field and flux concentrations to be propagated throughout the whole fracture surface. To achieve this, the solution outlined in Eq. (23) through to Eq. (29) is repeated for all the elements until a stable solution within a pre-set minimal tolerance is achieved.

Using the immediately downstream elements to define the flow contributions to the active element limits the downstream information to one element depth. However, the iteration over the whole fracture surface enables changes in the entire flow system to be taken into account. The advantage of this is that the streamline information (several elements depth) is satisfied, but the only interpretive information required on the behaviour of the flow field at the active element level is the requirement for the flow vectors of the neighbouring elements. This information is readily available.

Using this sub-time stepping approach and the propagation of information across the fracture surface, it was possible to evaluate the advective transport at time steps which would be clearly in violation of the courant control of advective flow.

Approximation of sub-grid scale channel flow

At 80 and 120 °C, there is a significant non-linear control on the flow through the fracture (Fig. 17). Inclusion of the kinetic control discussed above could not match this behaviour. This is considered due to the time frame over which the flow is operating, i.e. even at the higher temperatures, there is not enough contact time for the fluid in the fracture to demonstrate significant kinetic control. The key features observed are an increase in the permeability of the fracture, and a reduction in the Si concentration of the effluent.

Two processes are invoked to explain this observation

-

1.

The development of localised channel flow

-

2.

The reduction in reactive fluid solid contact area

In essence, both processes could be considered to be the same. In each case, the fluid flowing through the fracture removes some solid material, changing the geometry of the contact face with the fluid. In the case of channel flow, we assume that the flow causes a contiguous (joined up) change in the cross-sectional flow area; in the latter case, the removal of solid material reduced the area available for further dissolution, i.e. a rough surface becomes smoother.

Channel flow is a phenomenon which has been studied since the 1980s, (e.g. Abelin et al. 1994; Barton and de Quadros 1997; Brown et al. 1998; Tsang and Tsang 1987). As fluid flow is controlled by the cube of the aperture, there is a tendency for natural flow to form channels as the energetically most convenient way of passing through soluble solid faces. This allows more rapid fluid flow through the rock and leads to reducing amounts of dissolution with time by limiting the contact time of the fluid with the fracture face.

Channels are a phenomenon which is dependent on the geometry of the fracture surface. The numerical discretisation of the surface, if larger than the real scale of the development of channel flow in the experiment, requires sub-grid information to represent it. Experimental data through the examination of the woods metal cast suggested that there was no visible evidence of channels having been developed. However, the authors know of no other process which can develop over the time frames given which would lead to the hydraulic and chemical observations, and suggest that the scale of the channel flow development was so small as not to be observable, and possibly rather the term development of ‘local preferential flow paths’ should be applied.

Supporting evidence that unclearly defined preferential flow could have developed includes the fact that the hydraulic aperture of the fracture was less than 15 μm at the completion of the experiment, and the accuracy of the measurement of the fracture aperture through profiling was of the order of 10 μm. Equivalent permeability in stream flow is controlled by the harmonic mean of permeabilities along the flow path. This means that the hydraulic changes occurring require only a minimal change in the tighter areas of the fracture, and not the development of a well-defined channel. Evolution of the fracture aperture assuming the development of localised preferential flow paths suggests that a very small percentage of the fracture surface area actually controls the fluid flow behaviour, something which may not have been observable with the use of woods metal.

In the modelling approach, channels are assumed to form with a cross-sectional flow area much smaller than the 0.8 mm grid scale discretisation. The sub-grid scale understanding of the fractal geometry mentioned before allows the model to simulate the impact of preferential flow by redistributing the dissolution opening occurring across the fracture surface to a limited number of elements within the fracture plane. In practice, the fracture plane was divided broadly into a series of slices normal to the flow direction. The amount of dissolution occurring at each of these elements was evaluated, and then the dissolution redistributed in the slices such that the element showing most dissolution collected an extra amount of “dissolution” from the elements showing less dissolution. The total amount of dissolution was kept constant, and the amount redistributed controlled by parameterisation. A certain percentage of the slice cross-sectional flow area was allowed to grow, and also specified as a parameter. The simulation resolution was at a scale of 0.8 mm, with 55 elements comprising a slice, meaning that a minimal channel resolution of ~2 % (1/55) of the fracture surface could be represented. In practise to ensure channels developed, it was necessary to allow 12 % (6/55) of the fracture surface to develop ensuring good percolation throughout the fracture surface.

Change in the reactive surface area of the fracture

All DECOVALEX teams (Bond et al. 2014) showed that during the evaluation of the chemical dissolution of the fracture surface, the dissolution rates are orders of magnitude higher than the expected literature values. This is possibly due to the freshness of the fracture surface leading to a much larger surface area available for reactions to occur than just the flat smooth surface, again suggesting that sub-grid scale information should be introduced into the modelling approach. The “Surface Area Fitting Parameter” \(\alpha_{\text{c}}\) in Eq. (26) is used to take this extra roughness into account in this modelling approach. It was found that during parameterisation the value of \(\alpha_{\text{c}}\) could be demonstrably seen to change and reduce with time, suggesting that as the experiment progressed the “freshness” of the surface deteriorated. A further consideration is that the process of matrix diffusion coupled with stress corrosion could be enabling fluid access to large amounts of the rock matrix, captured numerically with the “Surface Area Fitting Parameter”. However, there are insufficient data to validate this at the current point in time. Evaluation of the dependency of this parameter suggested some relationship to the amount of flow through the fracture and with the temperature; however, the best dependency was with time, which suggests a further process not yet identified. It should be noted that in principle the process of changing the reactive surface area with time is not different from the mechanism behind the development of preferential flow paths, and that with informed selection of the parameterisation of \(\alpha_{\text{c}}\) an effect similar to channel flow could broadly be developed.

Results and discussion

The results of the methods described here for modelling the closure of the fracture surface and the reactive transport are presented. The model solves only the hydraulic parameters numerically and uses analytical and physical models of the system for the mechanical, chemical and temperature-dependent processes. The results of the modelling work are not taken as being an explicit realisation of parameters, rather they are a broad indication that the modelling approaches are viable and the key processes have been identified to the best of our knowledge. The experimental results and the model results of hydraulic aperture with time are presented in Fig. 18, and in comparison to all other DECOVALEX modelling teams participating in Fig. 19. Likewise, the chemical evolution of the effluent is presented in detail Fig. 20 and in comparison to all other DECOVALEX modelling teams in Fig. 21. Other relationships could have been illustrated; however, these figures include the key results from which all the other relationships can be derived. The parameterisation of the model is presented in Table 1. Contact area in the fracture is predicted initially circa 4.5 % and increases to 21 %, which matches closely with the model and experimental observations of Yasuhara et al. (2006).

Comparison of modelled versus observed hydraulic aperture for all DECOVALEX teams. (Adapted from Bond et al. 2014), NDA/Q Quintessa Ltd, UK, BGR/UFZ Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research—UFZ, Dept. Environmental Informatics, Leipzig, Germany, NRC U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), NDA/ICL Imperial College, London, United Kingdom, CAS Institute of Rock and Soil Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China, TUL Technical University of Liberec, Liberec, Czech Republic, NDA/UoE University of Edinburgh, UK

Comparison of modelled versus observed Si concentration in the effluent (ppm) for all DECOVALEX teams. (Adapted from Bond et al. 2014)

It is interesting to note that both the pressure solution fitting parameter and the surface area fitting parameter for dissolution are similar in size, and reduce similarly with time. These parameters represent the ratio of increase in pressure solution and chemical dissolution of the quartz against expected literature values for a smooth surface. Given that the fracture is artificial and fresh, it is reasonable to assume that a significant amount of roughness will be present. As time progresses, the surface becomes smoother and thereby the amount of material being transported away from the fracture surface reduces. Note also the discussion in the preceding section on matrix diffusion and stress corrosion effects not explicitly included in this model. These effects would also be expressed in the current model by an increase in the surface area of the fracture.

The largest differences between the current model predications and the experimental results are seen after the flow shut down at ~900 h and after the temperature increase at ~2900 h in terms of the development of the hydraulic aperture, and in terms of the silica content after the temperature increase at 2900 h. The event at 900 h was subject to some experimental uncertainty (Yasuhara, pers. comm). Possible mechanisms to replicate this behaviour are not included within the model, and there are limited data to validate modelling parameterisation.

After 2900 h, the temperature increase leads to a rapid response in terms of the hydraulic aperture. Although the model follows the profile, it does not respond as quickly. A possible explanation for this behaviour is related to the scale of discretisation of the model being unable to capture sub-element scale behaviour leading to an averaging effect. A possible cause of this effect is that the increased temperature has encouraged the removal of a key hydraulic feature causing an impedance to flow in the fracture surface. For example, a very small aperture within a generally larger flow channel has been widened. This would cause a significant increase in flow with a minimal amount of dissolution. At the scale of discretisation of the model, it is not possible explicitly to capture this “sub-element” scale type behaviour. However, the approach to replicate channel flow discussed in “Approximation of sub-grid scale channel flow” appears to go some way towards approximating this behaviour. As the modelled channel response is at the element scale, the rapid response of the hydraulic aperture is averaged out and whole element surfaces are dissolved, thereby leading to larger than measured Si concentrations. The model, therefore, captures the essence of the process, but without high resolution data to validate this behaviour (<10 μm vertical profile) and the necessary accuracy in terms of the discrete approximation of the fracture surface, it is not possible to explicitly represent this behaviour.

In this work, only the hydraulic system has been solved numerically, coupled with analytical and physical models adding sub-grid scale information into the numerical solution. During THMC modelling, a number of decisions must be made regarding which key processes and phenomena need to be represented to ensure computational efficiency. The modelling approach taken here has demonstrably been able to provide reasonable matches to the experimental data and where data are lacking, the results are validated against other modelling approaches. Introduction of further discrete processes beyond those mentioned may improve model fitting; however, data to validate the approaches are not available.

The scale of application of this model in this work is of the order of a few centimetres. Fluid flow in fractures occurs naturally over much larger scales. However, the key features captured in this model are orders of magnitude smaller than the scale of the sample examined, and so techniques developed to upscale this μm scale information to the cm scale are also valid for further upscaling considerations. A key contribution this work makes is in presenting efficient numerical methods for characterising the expected behaviour of some of the components of natural fracture systems. Understanding the response of the processes based upon a geo-statistical interpretation of the geometry of the fracture surfaces should, therefore, provide a key to upscaling this type of approach, and is currently under investigation.

Conclusions

A coupled process thermal, hydraulic, mechanical and chemical (THMC) model is presented for fracture flow, and validated against experimental data and cross comparison with results of other modelling teams within the DECOVALEX project (Bond et al. 2014). The model illustrates how the inclusion of physical and analytical models can provide further information to standard numerical solution procedures, and reduce the computational complexity required to achieve acceptable results. The mechanical and chemical transport processes were replaced with physical models, and by utilising the static nature of the temperature changes, only the hydraulic system required numerical solution.

Experimental data included a detailed fracture surface discretisation at a horizontal resolution of 50 μm, vertical profile discretisation with an accuracy of ~10 μm, fluid flow rates through the fracture of the order of a few ml/minute, pressure differential across the fracture of the order of a maximum of circa 1 MPa and effluent Si concentrations up to ~20 ppm. The fracture was confined under a static load, and at the completion of the experiment a cast of the fracture surface was taken. Throughout the experiment, the hydraulic aperture of the fracture changed as a result of the surface processes operating.

The mechanical behaviour of the fracture was simulated by relating the closure of the fracture aperture to the dissolution of the contact apertures, the local contact stress and the probability distribution of the aperture size. An iterative procedure was developed to allow implicit solution for aperture closure. Although for the purposes of the numerical implementation, the actual method of aperture closure is not important to the implementation, pressure solution was suggested as the key mechanism for aperture reduction, and chemical dissolution for increase in aperture size. Evaluation of a critical stress limiting the progress of pressure solution required the introduction of a sub-grid scale understanding of the nature of the contacts between the fracture surfaces. Development of a streamline-based model for dissolution allowed the kinetic control on dissolution to be evaluated without requiring the solution of the mass transport equation system.

The main features of the experimental data could be replicated. Although lying outside of the parametrical range as would be suggested by a literature study, comparison with other teams using different modelling approaches indicated internal consistency. A key contribution this work makes is presenting efficient numerical methods for simulating complex coupled process behaviour during fluid flow in natural fracture systems.

References

Abelin H, Birgersson L, Widen H, Agren T, Moreno L, Neretnieks I (1994) Channeling experiments in crystalline fractured rocks. J Contam Hydrol 15(3):129–158

Barton N, de Quadros EF (1997) Joint aperture and roughness in the prediction of flow and groutability of rock masses. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 34(3–4):252

Bernabé Y, Evans B, Fitzenz DD (2009) Stress transfer during pressure solution compression of rigidly coupled axisymmetric asperities pressed against a flat semi-infinite solid. Pure appl Geophys 166(5–7):899–925

Bond AE, Chittenden N, Fedors R, Lang PS, McDermott CI, Neretniecks I, Pan PZ, Sembera J, Watanabe N, Yasuhara H (2014) Coupled THMC modelling of a single fracture in novaculite for DECOVALEX-2015, DFNE 2014. In: 1st international conference on discrete fracture network engineering October 19–22, Vancouver, Canada, 2014. http://www.carma-rocks.ca/titles-dfne-2014/

Brown S, Caprihan A, Hardy R (1998) Experimental observation of fluid flow channels in a single fracture. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 103(B3):5125–5132

Celia MA, Nordbotten JM (2009) Practical modeling approaches for geological storage of carbon dioxide. Groundwater 47(5):627–638

Charney JG, Fjörtoft R, Neumann JV (1950) Numerical integration of the barotropic vorticity equation. Tellus 2(4):237–254

Choi JH, Seo YS, Chae BG (2013) A study of the pressure solution and deformation of quartz crystals at high pH and under high stress. Nucl Eng Technol 45(1):53–60

Courant R, Friedrichs K, Lewy H (1928) Über die partiellen differenzengleichungen der mathematischen Physik. Math Ann 100(1):32–74

Elias BP, Hajash A Jr (1992) Changes in quartz solubility and porosity due to effective stress: an experimental investigation of pressure solution. Geology 20(5):451–454

Eyring H (1935) The activated complex in chemical reactions. J Chem Phys 3(2):107–115

Finkel M, Liedl R, Teutsch G (1998) Modelling reactive transport of organic solutes in groundwater with a Lagrangian streamtube approach. Geochemical processes. Concept Models React Transp Soil Groundwater 115–133

Finkel M, Liedl R, Teutsch G (1999) Modelling surfactant-enhanced remediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ Model Softw 14:203–211

Glover PWJ, Matsuki K, Hikima R, Hayashi K (1999) Characterising rock fractures using synthetic fractal analogues. Geothermal Sci Technol (6):83–112

Gratier JP, Guiguet R, Renard F, Jenatton L, Bernard D (2009) A pressure solution creep law for quartz from indentation experiments. J Geophys Res B Solid Earth 114(3):B03403. doi:10.1029/2008JB005652

Helmholtz H (1853) Ueber einige Gesetze der Vertheilung elektrischer Ströme in körperlichen Leitern mit Anwendung auf die thierisch-elektrischen Versuche. Ann Phys 165(6):211–233

Istok J (1989) Groundwater modeling by the finite element method, American geophysical union, 2000 Florida avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20009. Water Resources Monograph Series, vol. 13, p 415

Kalbacher T, Mettier R, McDermott C, Wang W, Kosakowski G, Taniguchi T, Kolditz O (2007) Geometric modelling and object-oriented software concepts applied to a heterogeneous fractured network from the Grimsel rock laboratory. Comput Geosci 11(1):9–26

Kolditz O (1997) Strömung Stoff—und Wärmetransport im Kluftgestein. Bortraeger Verlag, Berlin-Stuttgart

Kolditz O, Bauer S, Bilke L, Böttcher N, Delfs JO, Fischer T, Görke UJ, Kalbacher T, Kosakowski G, McDermott CI, Park CH, Radu F, Rink K, Shao H, Shao HB, Sun F, Sun YY, Singh AK, Taron J, Walther M, Wang W, Watanabe N, Wu Y, Xie M, Xu W, Zehner B (2012) OpenGeoSys an open-source initiative for numerical simulation of thermo-hydro-mechanical/chemical (THM/C) processes in porous media. Environ Earth Sci 67(2):589–599

Koyama T, Fardin N, Jing L, Stephansson O (2006) Numerical simulation of shear-induced flow anisotropy and scale-dependent aperture and transmissivity evolution of rock fracture replicas. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 43(1):89–106

Lewis RW, Schrefler BA (1998) The finite element method in the static and dynamic deformation and consolidation of porous media. Wiley, Chichester

McDermott CI, Liedl R, Sauter M, Teutsch G (2005) The multi-shell model—a conceptual model approach. In: Dietrich P, Helmig R, Sauter M, Hötzl H, Köngeter J, Teutsch G (eds) Flow and transport in fractured porous media. Springer, New York, pp 306–321

McDermott CI, Lodemann M, Ghergut I, Tenzer H, Sauter M, Kolditz O (2006) Investigation of coupled hydraulic-geomechanical processes at the KTB site. Pressure-dependent characteristics of a long-term pump test and elastic interpretation using a geomechanical facies model. Geofluids 6(1):67–81

McDermott CI, Tarafder SA, Kolditz O, Schüth C (2007) Vacuum assisted removal of volatile to semi volatile organic contaminants from water using hollow fiber membrane contactors. II. A hybrid numerical-analytical modeling approach. J Membr Sci 292(1–2):17–28

McDermott CI, Walsh R, Mettier R, Kosakowski G, Kolditz O (2009) Hybrid analytical and finite element numerical modeling of mass and heat transport in fractured rocks with matrix diffusion. Comput Geosci 13(3):349–361

McDermott CI, Bond AE, Wang W, Kolditz O (2011) Front tracking using a hybrid analytical finite element approach for two-phase flow applied to supercritical CO2 replacing brine in a heterogeneous reservoir and caprock. Transp Porous Media 90(2):545–573

Miyakawa K, Kawabe I (2014) Pressure solution of quartz aggregates under low effective stress (0.42–0.61 MPa) at 25–45°C. Appl Geochem 40:61–69

Moës N, Dolbow J, Belytschko T (1999) A finite element method for crack growth without remeshing. Int J Numer Meth Eng 46(1):131–150

Mohammadi S (2008) Extended finite element method for isotropic problems, extended finite element method. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Hoboken, pp 61–116

Odling NE (1994) Natural fracture profiles, fractal dimension and joint roughness coefficients. Rock Mech Rock Eng 27(3):135–153

Ouyang T, Tamma KK (1996) ON adaptive time stepping approaches for thermal solidification processes. Int J Numer Meth Heat Fluid Flow 6(2):37–50

Pruess K (2005) Numerical studies of fluid leakage from a geologic disposal reservoir for CO2 show self-limiting feedback between fluid flow and heat transfer. Geophys Res Lett 32:14

Qin Q-H (2005) Formulation of hybrid Trefftz finite element method for elastoplasticity. Appl Math Model 29(3):235–252

Revil A (1999) Pervasive pressure-solution transfer. A poro-visco-plastic model. Geophys Res Lett 26(2):255–258

Stach S, Cybo J, Chmiela J (2001) Fracture surface—fractal or multifractal? Mater Charact 46(2–3):163–167

Sverjensky DA (1993) Physical surface-complexation models for sorption at the mineral-water interface. Nature 364(6440):776–780

Tsang C-F (1991) Coupled hydromechanical-thermochemical processes in rock fractures. Rev Geophys 29(4):537–552

Tsang YW, Tsang CF (1987) Channel model of flow through fractured media. Water Resour Res 23(3):467–479

Vilarrasa V, Koyama T, Neretnieks I, Jing L (2011) Shear-induced flow channels in a single rock fracture and their effect on solute transport. Transp Porous Media 87(2):503–523

Wang W, Görke UJ, Kolditz O (2011a) Adaptive time stepping with automatic control for modeling nonlinear H2M coupled processes in porous media. In: 45th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium

Wang W, Schnicke T, Kolditz O (2011b) Parallel finite element method and time stepping control for non-isothermal poro-elastic problems. Comput Mater Contin 21(3):217–235

Watanabe N, Wang W, Taron J, Görke UJ, Kolditz O (2012) Lower-dimensional interface elements with local enrichment. Application to coupled hydro-mechanical problems in discretely fractured porous media. Int J Numer Meth Eng 90(8):1010–1034

Witherspoon PA, Wang JSY, Iwai K, Gale JE (1980) Validity of cubic law for fluid flow in deformable rock fracture. Water Resour Res 16(6):1016–1024

Yasuhara H, Elsworth D (2006) A numerical model simulating reactive transport and evolution of fracture permeability. Int J Numer Anal Meth Geomech 30(10):1039–1062

Yasuhara H, Elsworth D (2008) Compaction of a rock fracture moderated by competing roles of stress corrosion and pressure solution. Pure appl Geophys 165(7):1289–1306

Yasuhara H, Elsworth D, Polak A (2004) Evolution of permeability in a natural fracture. Significant role of pressure solution. J Geophys Res B Solid. Earth 109(3):03201–03211

Yasuhara H, Polak A, Mitani Y, Grader AS, Halleck PM, Elsworth D (2006) Evolution of fracture permeability through fluid-rock reaction under hydrothermal conditions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 244(1–2):186–200

Zhang Y-J, Yang C-S, Xu G (2012) FEM analyses for T-H-M-M coupling processes in dual-porosity rock mass under stress corrosion and pressure solution. J Appl Math 2012:21

Zienkiewicz OC, Taylor RL (2005) The finite element method. Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results was conducted within the context of the international DECOVALEX Project (http://www.decovalex.org) with part funding from Radioactive Waste Management Limited (RWM) (http://www.nda.gov.uk/rwm), a wholly owned subsidiary of the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority. RWM is committed to the open publication of such work in peer reviewed literature, and welcomes e-feedback to “rwmdfeedback@nda.gov.uk”. Funding was also provided from the European Community’s Seventh framework Programme FP7/2007–2013 under the grant agreement No. 282900 as part of the PANACEA project in the context of the development of coupled process advective fluid flow dominated fracture models.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of a Topical Collection in Environmental Earth Sciences on "DECOVALEX 2015", guest edited by Jens T Birkholzer, Alexander E Bond, John A Hudson, Lanru Jing, Hua Shao and Olaf Kolditz.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McDermott, C., Bond, A., Harris, A.F. et al. Application of hybrid numerical and analytical solutions for the simulation of coupled thermal, hydraulic, mechanical and chemical processes during fluid flow through a fractured rock. Environ Earth Sci 74, 7837–7854 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4769-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4769-9