Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to describe the Canadian public’s understanding and perception of how death is determined in Canada, their level of interest in learning about death and death determination, and their preferred strategies for informing the public.

Methods

We conducted a nationwide cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of the Canadian public. The survey presented two scenarios of a man who met current criteria for neurologic death determination (scenario 1) and a man who met current criteria for circulatory death determination (scenario 2). Survey questions evaluated understanding of how death is determined, acceptance of death determination by neurologic and circulatory criteria, and interest and preferred strategies in learning more about the topic.

Results

Among 2,000 respondents (50.8% women; n = 1,015), nearly 67.2% believed that the man in scenario 1 was dead (n = 1,344) and 81.2% (n = 1,623) believed that the man in scenario 2 was dead. Respondents who believed that the man was not dead or were unsure endorsed several factors that may increase their agreement with the determination of death, including requiring more information about how death was determined, seeing the results of brain imaging/tests, and a third doctor’s opinion. Predictors of disbelief that the man in scenario 1 is dead were younger age, being uncomfortable with the topic of death, and subscribing to a religion. Predictors of disbelief that the man in scenario 2 is dead were younger age, residing in Quebec (compared with Ontario), having a high school education, and subscribing to a religion. Most respondents (63.3%) indicated interest in learning more about death and death determination. Most respondents preferred to receive information about death and death determination from their health care professional (50.9%) and written information provided by their health care professional (42.7%).

Conclusion

Among the Canadian public, the understanding of neurologic and circulatory death determination is variable. More uncertainty exists with death determination by neurologic criteria than with circulatory criteria. Nevertheless, there is a high level of general interest in learning more about how death is determined in Canada. These findings provide important opportunities for further public engagement.

Résume

Objectif

Notre objectif était de décrire la compréhension et la perception du public canadien quant à la façon dont le décès est déterminé au Canada, son niveau d’intérêt à en apprendre davantage sur le décès et la détermination du décès, et ses stratégies préférées pour informer le public.

Méthode

Nous avons réalisé un sondage transversal national auprès d’un échantillon représentatif de la population canadienne. L’enquête a présenté deux scénarios : un homme qui répondait aux critères actuels de détermination d’un décès neurologique (scénario 1) et un homme qui répondait aux critères actuels de détermination d’un décès cardiocirculatoire (scénario 2). Les questions de l’enquête évaluaient la compréhension de la façon dont le décès est déterminé, l’acceptation de la détermination du décès selon des critères neurologiques et circulatoires, et l’intérêt et les stratégies préférées pour en apprendre davantage sur le sujet.

Résultats

Parmi les 2000 répondants (50,8 % de femmes; n = 1015), près de 67,2 % ont estimé que l’homme du scénario 1 était décédé (n = 1344) et 81,2 % (n = 1623) ont estimé que l’homme du scénario 2 était décédé. Les répondants qui croyaient que l’homme n’était pas décédé ou qui n’étaient pas sûrs ont acquiescé à plusieurs facteurs qui pourraient accroître leur accord avec la détermination du décès, y compris le besoin de plus de renseignements sur la façon dont le décès a été déterminé, la consultation des résultats d’imagerie et des tests cérébraux et l’opinion d’un troisième médecin. Les prédicteurs de non-conviction que l’homme dans le scénario 1 était décédé étaient le fait d’être plus jeune, le fait d’être mal à l’aise avec le sujet de la mort et la croyance en une religion. Les prédicteurs de non-conviction à l’égard du décès de l’homme dans le scénario 2 étaient le fait d’être plus jeune, d’être résident du Québec (comparativement à l’Ontario), d’avoir complété des études secondaires et la croyance en une religion. La plupart des répondants (63,3 %) ont indiqué qu’ils souhaiteraient en apprendre davantage sur le décès et la détermination du décès. La plupart des répondants préféraient recevoir de l’information sur le décès et la détermination du décès de leur professionnel de la santé (50,9 %) et de l’information écrite fournie par leur professionnel de la santé (42,7 %).

Conclusion

Parmi le public canadien, la compréhension de la détermination du décès neurologique et cardiocirculatoire est variable. Il existe plus d’incertitude en matière de détermination du décès selon des critères neurologiques que selon des critères cardiocirculatoires. Néanmoins, il existe un grand intérêt général à en apprendre davantage sur la façon dont le décès est déterminé au Canada. Ces résultats offrent d’importantes possibilités de participation accrue du public à l’avenir.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

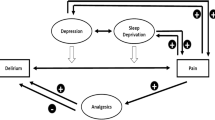

When is a person dead? This is a question that health care professionals, society, and the public have grappled with over time, especially given advances in medical technology in critical care with organ and mechanical support.1,2 Clinically, death is defined as permanent cessation of brain function.3 This can result from cessation of blood circulation to the brain and/or from devastating brain injury, and is assessed by circulatory or neurologic criteria, respectively.4 While there is widespread national and international acceptance in the medical community of both ways of determining death, there are inconsistencies in the criteria and practices of death determination. The World Brain Death Project was created to improve the rigor of death determination by neurologic criteria (DNC) and harmonize the criteria internationally.5

Confusion regarding death definitions has been shown in multiple countries.6,7 In particular, there is poor understanding of neurologic death and confusion with other conditions such as coma and persistent vegetative state.6 Fewer studies have examined public understanding and acceptance of death determination by circulatory criteria (DCC).1 Our recent scoping review revealed that the public misunderstanding stems more from confusion about the medical and legal facts concerning death determination.1 We are unaware of surveys that explore and compare the attitudes and perceptions of the Canadian public toward both approaches to death determination.

We aimed to describe the Canadian public’s understanding and perception of how death is determined in Canada, their level of interest in learning about death and death determination, and their preferred strategies for informing the public. This project is part of a larger study in collaboration with the Canadian Blood Services, the Canadian Critical Care Society, and the Canadian Medical Association to produce a clinical practice guideline that supports a brain-based definition of death and criteria for death determination by neurologic or circulatory criteria, featured as the centerpiece of this month’s Special Issue of the Journal.4

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional web-based survey of the Canadian public. Ethics approval was granted from the Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board (Protocol number, 20210369-01). All respondents provided informed consent electronically before completing the survey.

Survey development

The survey instrument was developed following the methods described by Burns et al.8 First, the study investigators with expertise in both adult and pediatric critical care (A. S., K. H., M. W., S. Sh.) and research methodology (A. S., K. H., F. P., S. Su.), along with family and public partners (R. C., J. B., H. B., K. E.-P.), developed two scenarios and a series of questions designed to explore the public’s understanding of death and how death is determined in Canadian intensive care units (ICUs) and their perceptions about two types of practices: DNC (e.g., brain death) and DCC. The survey questions were modified from the survey instrument developed by Skowronski et al.7 and were informed by the results of scoping reviews.1,2 We refined the initial list of questions based on feedback from medical experts, experienced researchers, and the project’s public and family partners.

We then pretested the initial draft of the survey by asking patients, family, and public partners on the guideline panel to complete the survey and provide feedback on its comprehensibility and likelihood of yielding pertinent information regarding the public’s knowledge and perceptions about death determination. Finally, Ipsos Group, a professional survey development company contracted to distribute the survey, conducted pilot testing of the survey among 50 members from their prerecruited nationwide panel. The investigators reviewed all responses obtained from pilot respondents to identify and refine survey content and questions to ensure further clarity. Pilot data were excluded from the final analysis.

Description of the survey instrument

The final survey instrument is shown in Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) eAppendix 1. The survey questions centered around two scenarios (see Table 1), one describing a case of DNC and another describing a case of DCC. Each scenario was followed by a series of Likert scale and open-ended questions asking respondents to indicate whether they agreed that the individual described in the scenario was dead (yes, no, or unsure). We then asked respondents to indicate their level of confidence in their response (on a scale of 1 to 10), select the reasons for this opinion from a list (four-point Likert scale), and select factors that they feel may influence or change their perspective about whether or not the man is dead. We then asked respondents to answer a series of questions about their level of interest in learning more about death determination, preferred sources of information, level of comfort with the topic of death, and personal experience with supporting a dying person in the ICU. Finally, we asked a series of standard demographic questions.

Sample size calculation

We derived a minimum sample size estimate of 385 using a standard survey sample size calculation that incorporates population size (approximately 36.3 million in Canada), a confidence level of 95%, and a confidence interval (CI) of 5%. We planned to collect 2,000 responses to allow for subgroup analyses.

Survey distribution

The survey was conducted between 27 September to 15 October 2021, by Ipsos Group (Toronto, ON, Canada), an independent survey distribution company.9 Respondents were selected from Ipsos’ database of prerecruited panelists as well as their affiliate networks. Ipsos uses a matrix approach based on the latest Statistics Canada census data to ensure that the selected respondents are representative of the Canadian population with respect to age, sex, and province of residence. Please see ESM eAppendix 2 (Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys [CHERRIES]) for details.10

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to report sample characteristics and responses to all survey items (means and standard deviations, medians and interquartile ranges [IQRs], or frequencies and proportions, as appropriate).

We performed inferential analyses to identify factors independently associated with disbelief that the man is dead. Predictor variables were selected a priori by purposeful selection and included age, sex, region of residence, highest level of education achieved, subscribing to a religion, marital status, having a close friend or family member who died in the ICU, and comfort level with the topic of death. We then performed univariable analyses comparing respondents who believed the man was dead to those who did not believe the man was dead (i.e., believed the man was not dead or were unsure). For categorical data, Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact test were used. Student’s t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann–Whitney U test) were used to compare continuous data between the groups. All inferential analyses accounted for weighting of the survey data.

Next, we performed multivariable logistic regression analyses separately for each scenario. Variables used to weight the survey data (age, sex, region) were forced into all models. Results are presented for the full models, including all predictors of interest, and for reduced models, performed using the backward selection method whereby the significance level to remain in the model was set at 0.05. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs were reported to quantify the relationship between independent variables and disbelief that the man was dead. Regression diagnostics were performed to ensure that the assumptions of logistic regression were met. Specifically, multicollinearity was assessed by calculating the correlation between independent variables using a threshold of 0.8. Linearity of age and the log odds of age were assessed by including that interaction term in the model. The C-statistic was used to quantify discrimination of the model. All data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the 2,000 respondents are summarized in Table 2. Half of respondents (n = 1,015, 50.8%) were women and were representative of the Canadian population with respect to age distribution and province of residence. Most respondents were university/college educated (n = 1,181, 59.1%), married or in a common-law partnership (n = 1,080, 55.3%), self-identified as “white” in ethnicity (n = 1,570, 80.4%), subscribed to a religion or faith (n = 1,105, 56.7%). Of the 2,000 respondents, 694 (34.7%) reported having supported a family member or close friend who died in an ICU and 679 (34%) indicated that they are uncomfortable with the topic of death.

Is the man dead?

For scenario 1 (DNC), 1,344 respondents (67.2%) believed that the man was dead, 382 (19.1%) believed that the man was not dead, and 274 (13.7%) were unsure (Fig. 1A). In scenario 2 (DCC), 1,623 (81.2%) believed that the man was dead, 164 (8.2%) believed that the man was not dead, and 213 (10.7%) were unsure (Fig. 1B). The reasons for belief that the man is dead, not dead, or unsure for scenarios 1 and 2 are presented in Figs 1 and 2, respectively.

Overall, 749 respondents (37.5%) were discordant in their beliefs across the two scenarios. Among respondents who agreed that the man in scenario 1 is dead, 87 (4.4%) believed that the man in scenario 2 is not dead, and 118 (5.9%) were unsure about whether the man is dead in scenario 2. Among respondents who believed that the man in scenario 2 is dead, 286 (14.3%) believed that the man in scenario 1 is not dead and 198 (9.9%) were unsure about whether the man is dead in scenario 1.

Level of confidence in response

Respondents who believed the man to be dead in scenario 1 had a high level of confidence in their response (median [IQR] score of 8.5 [7.5–9.3] out of 10). Confidence scores were lower for those who believed the man is not dead in scenario 1 (median [IQR] score of 6.7 [5.0–8.4] out of 10). Similarly, in scenario 2, confidence levels were higher among those who believed the man to be dead (median [IQR] score 9.0 [8.0–9.5]) than among those who believed the man is not dead (median [IQR] score 5.6 [3.7–7.3]).

The majority of respondents who believed that the man was dead endorsed that they “have enough information on how death is determined” (scenario 1: n = 687, 51.1%; scenario 2: n = 756, 46.6%), indicated that they agreed with how death was determined in each scenario (scenario 1: n = 736, 54.7%; scenario 2: n = 930, 57.3%), and that they “trust the doctors and nurses to make this determination” (scenario 1: n = 923, 68.7%; scenario 2: n = 1,010, 62.2%).

For respondents who believed that the man was not dead or were unsure, the factors that contributed to this opinion are shown in Table 3. Most respondents indicated that they “need more information on how death is determined.”

Respondents who believed that the man was not dead or were unsure endorsed several factors that may increase their agreement with the determination of death (Table 4). The most frequently endorsed factors included “more information about how death was determined,” “seeing the results of brain imaging/tests,” and “a third doctor’s opinion.” In scenario 2, five respondents endorsed that waiting more than five minutes would increase their agreement that the man is dead.

Factors associated with responses

In Scenario 1, respondents who did not believe the man was dead or were unsure were younger (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.81), uncomfortable with the topic of death (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.61), and subscribed to a religion (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.30 to 2.01). There was no association between education level, region, or marital status (ESM eAppendix 3).

In scenario 2, respondents who did not believe the man was dead or were unsure were younger (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.95), resided in Quebec relative to Ontario (OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.49 to 2.79), had a high school education compared with college/university degree (reference category), subscribed to a religion (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.72), and were unmarried (ESM eAppendix 3).

There was no association with gender, comfort level with the topic of death, or having known a family member/close friend who died in the ICU in either scenario. Given the small number of respondents within each ethnic group, we did not include this characteristic in the regression model (ESM eAppendix 3).

Stopping intensive care treatments in case of DNC

In scenario 1, most agreed that doctors should stop intensive care treatments (n = 1,599, 80%). The various responses to why intensive care treatments should or should not be continued are shown in Table 5. Nearly all of those who agreed, believed that without brain function, the man’s quality of life would be poor (95.7%).

Preferred sources of knowledge

Over half of respondents (n = 1,266; 63.3%) indicated they would be interested in learning more about how death is defined and determined in Canada. There were no differences between men and women and their interest (n = 637, 62.8% women, n = 625, 64.0% men). Nevertheless, those whose highest level of education was a postgraduate degree were more likely to indicate they have an interest in learning more (postgraduate training, n = 269, 70.4%; university/college, n = 752, 63.7%; high school, n = 229, 60.9%). In addition, those who had supported a family member/close friend die in the ICU were more likely to respond that they are interested in learning more about how death is defined and determined than those who had not had such an experience (n = 487, 70.2% vs n = 749, 60.3%, respectively).

Preferred sources of information on death determination among all respondents, and among younger respondents (between the ages of 18 and 34), are presented in Fig. 2. Overall, 50.9% of respondents indicated that they would prefer to receive information through their own doctor or health care professional and 42.7% preferred to receive written information such as a pamphlet provided by their doctor or health care professional.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional nationwide survey of the Canadian public, we found that the majority of Canadians agree that a person is dead when presented with scenarios that conform to currently accepted standards for death determination by either neurologic or circulatory criteria. There was a higher level of agreement when presented with a scenario of DCC compared with DNC. Those who were unsure or stated not dead for both scenarios were less confident in their response, and the majority did endorse various factors that could possibly change their response to accepting the person is dead.

While over two-thirds of Canadians surveyed agreed that the man is dead in scenario 1 (DNC), it is notable that about a third of respondents believed that the man is not dead or were unsure. Those who responded unsure or disagreed with the death determination were less confident in their response. Previous studies on public perspectives have shown considerable variation in their agreement with DNC.7,11,12,13,14,15,16 Furthermore, in scenario 1, we found that most agreed that doctors should stop intensive care treatments (80%). This is slightly higher than in the Skowronski et al. study, where 75.7% indicated the patient’s “life support” should be removed.7 Both studies suggest that the degree of brain damage and patient’s quality of life are important in deciding to stop intensive care treatments. The formal determination of death may be less important with respect to this decision. Of note, we intentionally did not use the term “life support,” and this may have impacted responses, as the term “life” erroneously implies that the person is still alive. Use of terms such as “life support” in the context of DNC can be perceived as conflicting information to the public and to family members in the ICU, misrepresenting individuals who are already dead.17,18 In contrast, it could also be argued that use of terms such as “brain death” may bias the respondents toward agreement with death determination.

There is a paucity of data on public perspectives of DCC.1 In our study, we found that a higher proportion of the public agreed that the man is dead in a scenario of DCC compared with DNC. Nevertheless, nearly one-fifth of the Canadian public were still unsure or did not believe the man was dead in this scenario, with most in this group (nearly 70%) responding that not enough time had passed (five minutes) after the heart had stopped to ensure that he was dead. A recent international study of patients dying in the ICU following withdrawal of life sustaining measures provides evidence for this time period as the primary finding was that the longest period of pulselessness that was followed by resumption of cardiac and pulsatile activity was four minutes 20 sec.19 Education and provision of information based on research data may alleviate public concerns in this group. That said, additional questions exist among this group that require attention, including concerns that "even if his heart stopped, his brain may not have died.”

An Australian survey of the public found no differences in demographics of those respondents that agreed the patient is dead, were unsure, or believed the patient not to be dead.7 In contrast, our data revealed multiple factors that predicted opinions about death determination. In both scenarios, those who believed the man is not dead or were unsure were younger and subscribed to a religion, with the latter variable being a stronger predictor of non-agreement in the neurologic criteria scenario than in the circulatory criteria scenario. In the DNC scenario respondents also tended to be less comfortable with the topic of death, whereas with the DCC scenario they were more likely to have a high school education and be unmarried. Province of residence was the strongest predictor of disagreement that the person is dead in the DCC scenario; compared with Ontario residents, those residing in Quebec had two times the odds of disagreeing that the man is dead, suggesting that sociocultural factors may play an important role beyond respondents’ individual demographic characteristics.

While there is a notable number of Canadians who either disagree or are unsure of the determination of death regardless of the criteria used, there are clear opportunities identified to increase understanding and acceptance of these determinations. In our study, only 8.4% and 3.2% of those who disagreed that the man is dead in scenarios 1 and 2, respectively, said that nothing would change their mind. Having more information on how death is determined, seeing the results of brain imaging/tests, a third doctor’s opinion, and more time to process the information were the top responses that would help to agree with determination of death for those who disagreed or were unsure if the man is dead. These findings are complementary to our investigation of family members’ understanding and acceptance of DNC, where we found facilitators to acceptance of the determination of death included provision of and repetition of information over time including visual information such as seeing the imaging, and witnessing the determination, in particular the apnea test.20 Improving public knowledge of death and how it is determined prior to learning of a loved one’s critical illness and death may improve understanding and acceptance during a time of grief and stress, during which it can be difficult to process information,21,22 in particular around complex concepts of death. Further, it is imperative to continue to improve health care professionals’ positive communication methods, using strategies grounded in social science research, to better engage community members in discussions about death.

Interestingly, there is a high level of general interest in learning more about how death is determined in Canada. This includes those who disagreed with the determination of death in either scenario. Respondents with a higher level of education and those who had previously supported a family member/close friend who died in the ICU were more likely to endorse interest in learning more about death and death determination, perhaps reflecting their greater understanding of the complexities in this topic. Studies have shown that the media, including televised dramas, plays an important role in shaping public views of death.1,23,24 Unfortunately, these sources also perpetuate misinformation on how death is defined and determined along with the implications, creating confusion and distrust.1 Access to accurate information is essential for preserving public trust. Indeed, we found that very few respondents preferred to receive information about death determination from media sources, including social media and posts by non-medical public figures. That the Canadian public prefers learning more about this topic from reputable sources provides an important opportunity to correct misinformation and build trust in the health care system.

Our study provides information on the public’s preferred modes of receiving information. About half of respondents indicated that they would prefer to receive information through their own doctor or health care professional. Unfortunately, significant barriers exist within the primary care setting around having conversations about serious illness, including system level, clinician, and patient factors.24 Evidence suggests that discussions about end-of-life care do not routinely occur in the outpatient setting.24,25 That said, programs and interventions have shown significant increases in the frequency of discussions and in documentation of end-of-life wishes.25 Early discussion or provision of written materials from health care professionals, with whom patients have formed long-term relationships and trust, on death and death determination may be combined with such programs. These programs could help prepare patients for end-of-life care discussions and also encourage further dialog, improving knowledge and understanding of the issues involved, while providing opportunity for clinicians to discuss and better understand individual values and wishes.

This study has several limitations. As with all surveys, our results may be prone to selection bias, which may skew the findings toward those who are mostly comfortable with the topic of death. In addition, the survey was only distributed electronically, so members of the public without access to the internet and electronic devices were excluded. Because survey questions were presented in the same order for all respondents, it is conceivable that the order of presentation of the cases (neurologic determination first, circulatory determination second) may have influenced or primed respondents. While we cannot exclude the possibility that some respondents may not have fully understood the scenarios or questions, we attempted to minimize risk by engaging members of the public in the development of the research protocol and survey tool along with rigorous pretesting of the survey content. Finally, our sample was composed of a high number of “higher than high school” respondents, and given the small number of minority groups, we were not able to evaluate other predictors such as ethnicity or specific religious affiliations.

This study also has several strengths. This is the first study reporting on the perspectives of the Canadian public with respect to death and death determination. While numerous international studies have explored public perspectives of brain death, this is also one of the largest studies to report on public perspectives on death determination by both neurologic and circulatory criteria. The nationwide sample consisted of respondents who were representative of the Canadian population in age, gender, and geographical region. We developed the survey using established survey methodology.8 Furthermore, we engaged with members of the public throughout the development of the protocol and survey instrument and conducted rigorous pretesting of the survey tool.

The findings of this study reveal several areas for further research. Qualitative data will offer a richer, more in-depth picture of the perspectives of Canadians to contextualize the findings of this survey. To this end, a focus group study is currently underway to further explore public perspectives regarding the definition and determination of death in Canada. Our study focused broadly on public perspectives and understanding of death and death determination; we did not specifically include cases or questions regarding organ donation. Death determination in the context of organ donation may impact responses and hence this area requires further investigation and can be contrasted to our findings in future studies.

Conclusion

Our study examined perspectives of the Canadian public with respect to death determination and found that the majority of Canadians agree with death determined by both neurologic and circulatory criteria. We found differences in perspectives and understanding in these cases, including less acceptance and uncertainty with DNC. Our study also shows that Canadians have a high level of general interest in learning more about how death is determined in Canada. These findings provide important opportunities for further public engagement.

References

Zheng K, Sutherland S, Hornby L, Shemie SD, Wilson L, Sarti AJ. Public understandings of the definition and determination of death: a scoping review. Transplant Direct 2022; 8: e1300. https://doi.org/10.1097/txd.0000000000001300

Zheng K, Sutherland S, Hornby L, Shemie SD, Wilson L, Sarti AJ. Healthcare professionals' understandings of the definition and determination of death: a scoping review. Transplant Direct 2022; 8: e1309. https://doi.org/10.1097/txd.0000000000001309

Murphy NB, Hartwick M, Wilson LC, et al. Rationale for revisions to the definition of death and criteria for its determination in Canada. Can J Anesth 2023; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02407-4.

Shemie SD, Wilson LC, Hornby L, et al. A brain-based definition of death and criteria for its determination after arrest of circulation or neurologic function in Canada: a 2023 Clinical Practice Guideline. Can J Anesth 2023; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02431-4.

Greer DM, Shemie SD, Lewis A, et al. Determination of brain death/death by neurologic criteria: the World Brain Death Project. JAMA 2020; 324: 1078–97. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.11586

Siminoff LA, Burant C, Youngner SJ. Death and organ procurement: public beliefs and attitudes. Soc Sci Med 2004; 59: 2325–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.029

Skowronski G, O'Leary MJ, Critchley C, et al. Death, dying and donation: community perceptions of brain death and their relationship to decisions regarding withdrawal of vital organ support and organ donation. Intern Med J 2020; 50: 1192–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15028

Burns KE, Duffet M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ 2008; 179: 245–52. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.080372

Ipsos. Homepage. Available from URL: https://www.ipsos.com (accessed August 2022).

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004; 6: e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34

Al Bshabshe AA, Wani JI, Rangreze I, et al. Orientation of university students about brain-death and organ donation: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2016; 27: 966–70. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.190865

DuBois JM, Anderson EE. Attitudes toward death criteria and organ donation among healthcare personnel and the general public. Prog Transplant 2006; 16: 65–73.

Febrero B, Ríos A, Martínez-Alarcón L, et al. Knowledge of the brain death concept among adolescents in southeast Spain. Transplant Proc 2013; 45: 3586–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.10.014

Ríos A, López-Navas AI, Flores-Medina J, et al. Ecuadorian population residing in Spain and their knowledge of brain death concept. Transplant Proc 2020; 52: 432–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.12.013

Ríos A, López-Navas AI, Flores-Medina J, et al. Knowledge of the brain death concept among the Puerto Rican population residing in Florida. Transplant Proc 2020; 52: 449–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.11.042

Ríos A, López-Navas A, López-López A, et al. Do Spanish medical students understand the concept of brain death? Prog Transplant 2018; 28: 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1526924817746687

Crippen D. Changing interpretations of death by neurologic criteria: the McMath case. J Crit Care 2014; 29: 673–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.06.020

Long T. Brain-based criteria for diagnosing death: what does it mean to families approached approached about organ donation? Southampton: University of Southhampton; 2007.

Dhanani S, Hornby L, van Beinum A, et al. Resumption of cardiac activity after withdrawal of life-sustaining measures. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 345–52. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2022713

Sarti AJ, Sutherland S, Meade M, et al. Death determination by neurologic criteria—what do families understand? Can J Anesth 2023; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02416-3.

Sarti AJ, Sutherland S, Healey A, et al. A multicenter qualitative investigation of the experiences and perspectives of substitute decision makers who underwent organ donation decisions. Prog Transplant 2018; 28: 343–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1526924818800046

Kilcullen JK. “As good as dead” and is that good enough? Public attitudes toward brain death. J Crit Care 2014; 29: 872–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.06.018

Febrero B, Ros I, Almela-Baeza J, et al. Knowledge of the brain death concept among older people. Transplant Proc 2020; 52: 506–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.09.019

Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174: 1994–2003. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271

Lakin JR, Arnold CG, Catzen HZ, et al. Early serious illness communication in hospitalized patients: a study of the implementation of the Speaking About Goals and Expectations (SAGE) program. Healthc (Amst) 2021; 9: 100510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100510

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study. Aimee J. Sarti, Kimia Honarmand, Stephanie Sutherland, Laura Hornby, Lindsay Wilson, and Sam Shemie contributed to acquisition of data, analysis of data, interpretation of data, and drafting of the article. Fran Priestap contributed to analysis of data, interpretation of data, and drafting of the article. All authors contributed critical review and revision of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Laura Hornby is a paid consultant for Canadian Blood Services.

Funding statement

This work was conducted as part of the project entitled, “A Brain-Based Definition of Death and Criteria for its Determination After Arrest of Circulation or Neurologic Function in Canada,” made possible through a financial contribution from Health Canada through the Organ Donation and Transplantation Collaborative and developed in collaboration with the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Blood Services, and the Canadian Medical Association. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada, the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Blood Services, or the Canadian Medical Association.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Helen Opdam, Guest Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarti, A.J., Honarmand, K., Sutherland, S. et al. When is a person dead? The Canadian public’s understanding of death and death determination: a nationwide survey. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 70, 617–627 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02409-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02409-2